Retrospective comparison of cognitive behavioral therapy and symptom-specific medication to treat anxiety and depression in throat cancer patients after laryngectomy

Jing CHEN*, Chuancheng CHEN, Shengli ZHI

•Original article•

Retrospective comparison of cognitive behavioral therapy and symptom-specific medication to treat anxiety and depression in throat cancer patients after laryngectomy

Jing CHEN1*, Chuancheng CHEN2, Shengli ZHI1

cognitive behavior therapy, laryngectomy, depression, anxiety disorders

1. Introduction

Throat cancer is one of the most common types of cancers in the head and neck. A laryngectomy is the most effective treatment for patients with advanced throat cancer, but it is an invasive procedure that results in the loss of the ability to speak. Patients undergoing laryngectomy experience a variety of stresses including concerns about the cancer, long-lasting adverse effects of radiotherapy, loss of voice and financial problems.These stressors often lead to high levels of anxiety or depressive symptoms that can suppress the immune system and, thus, may accelerate progression of the cancer.[1]Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a type of psychological treatment that aims to change patients’maladaptive thinking about stressors and, thus,positively influence affect and behavior.[2]Theoretically,the use of motivational strategies, improvement of self-awareness and activation of social support networks encouraged by CBT can help cancer patients gain a sense of control over the illness and increase their confidence to fight the illness.[3]CBT does not require that the patient be able to communicate orally, so some researchers have proposed the use of CBT to treat patients with throat cancer who develop clinically serious symptoms of anxiety or depression.[4]Despite the plausibility of using CBT with patients who communicate with the therapist in writing, there has been no empirical evidence about the effectiveness of CBT in the treatment of anxiety and depression among patients who have undergone laryngectomy.

The current retrospective study reviewed and analyzed the medical charts of 119 patients with throat cancer who were diagnosed with anxiety disorders or depression after a laryngectomy.

2. Sample and methods

2.1 Sample

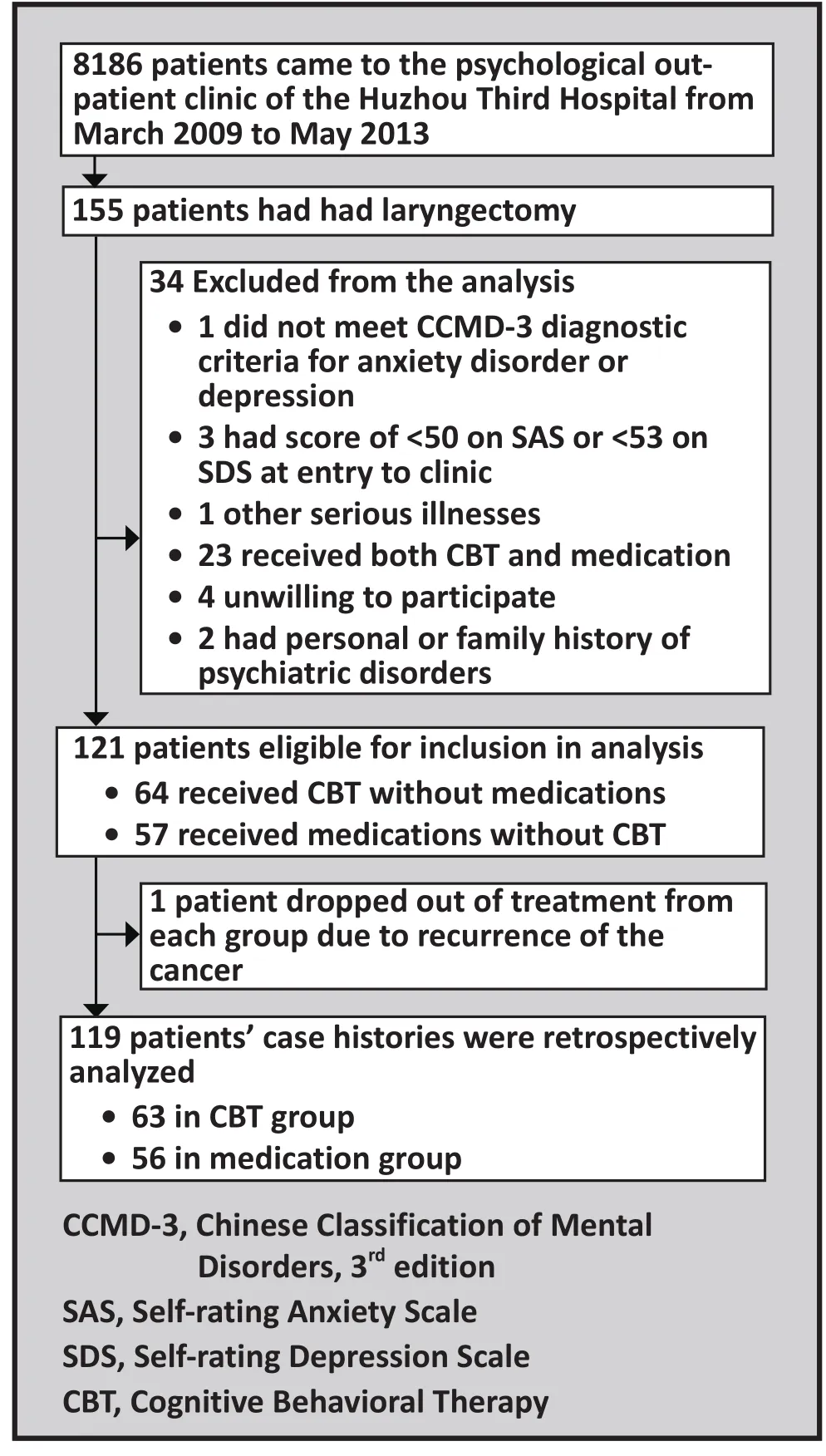

We reviewed medical charts of 155 patients who sought treatment at the psychological outpatient clinic in the Third People’s Hospital between March 2009 and May 2013 for anxiety disorders or depression (diagnosed according to criteria specified in the Third Edition of the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, CCMD-3[5]) after a laryngectomy. As shown in Figure 1, after removing 36 cases due to various exclusion criteria,there were 119 who completed treatment for anxiety and depression, including 63 who received CBT without medication and 56 who received medication (buspirone,sertraline or both buspirone and sertraline) without CBT. The time lag between the laryngectomy and the beginning of psychological treatment varied from 0.5 to 6.5 months. Eighty-five of these patients (71%) were referred by the otolaryngology departments of the No. 1 Hospital of Huzhou or the Central Hospital of Huzhou; the remaining 34 patients were self-referred.The proportion of self-referred patients did not differ between patients who elected to use CBT and those who elected to use medication.

Among the 119 patients, 114 were males and 5 were females; 117 had squamous cell carcinoma and 2 had adenocarcinoma. They were 45 to 76 years of age;the mean (sd) age was 61.5 (7.8) years. None of the patients had a personal or family history of psychiatric disorders. No statistically significant differences were found between the CBT group and the medication group in mean age (62.6 [8.3] v. 60.4 [7.3]; t=1.50, p=0.136),gender (male 95.2% v. 96.4%; χ2=0.00, p=1.000), level of education (proportions of illiterate, primary school,high school and college graduates in the CBT group were 25.4%, 42.9%, 22.2% and 9.5%, respectively versus 25.0%, 35.8%, 28.6% and 10.7% in the medication group; Mann-Whitney Z=0.548, p=0.583), or income level (44.4% v. 50.0% had a monthly income of more than 6000 Renmibi [about $1000, $US]; χ2=0.37,p=0.544). The CBT and medication groups did not differ in the prevalence of neck lymph node metastasis (63.5%v. 60.7%; χ2=0.10, p=0.755), self-report of fear of cancer(84.1% v. 87.5%; χ2=0.27, p=0.600), or self-report of being introverted (69.8% v. 57.1%; χ2=2.07, p=0.150).

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Third Hospital of Huzhou.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 CBT

The physician who provided CBT to all the patients in the CBT group was a licensed psychiatrist and counselor. CBT was delivered one-on-one; each session was documented in the out-patient records.Patients communicated with the clinicians by writingtheir responses. There were a total of 12 sessions over a period of eight weeks (one or two 1.0- to 1.5-hour sessions per week). The content of the sessions focused on discussion of patients’ understanding of their experiences of cancer treatment and on their interpretation of the difficulties they were experiencing in their daily lives. Among the 64 patients who started CBT, 63 (98.4%) completed all 12 CBT sessions over the 8-week treatment period. None of these patients received antidepressant or anti-anxiety medications.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study

2.2.2 Medication

In the medication group, 56 of the 57 enrolled patients(98%) adhered with the medications over the entire 8-week treatment period. Among them,11 patients with anxiety who did not have prominent depressive symptoms were administered buspirone (15 to 30 mg/d); 9 patients with depression who did not have prominent anxiety were administered sertraline (50 to 100 mg/d); and 36 patients with comorbid anxiety and depression were administered both buspirone (15 to 20 mg/d) and sertraline (50 to 100 mg/d). None of these patients received CBT or any other psychotherapeutic treatment.

2.2.3 Assessments

Before and after treatment patients completed the Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS).[6]SAS and SDS are commonly used assessment tools in China with good validity and reliability.[7-9]Each scale contains 20 items rated on a 4-level Likert scale (‘not at all or just a little of the time’,‘some of the time’, ‘a good part of the time’, and ‘most of the time’). SAS has 15 positive items and 5 negative(i.e., reverse-scored) items; SDS has 10 positive items and 10 negative items. The standardized score is the total of the raw item scores (score 1 to 4 for each item)of the 20 items times 1.25, which results in a theoretical range of standardized scores of 25 to 100. The clinical threshold of SAS is 50; scores in the 50-59, 60-69, and 70-100 ranges correspond to mild, moderate and severe anxiety, respectively. For the SDS, the clinical threshold is 53; scores in the 53-62, 63-72 and 72-100 ranges correspond to mild, moderate, and severe depression,respectively.

2.2.4 Statistical analyses

SPSS 16.0 was used for analysis. One-sample (paired)t-test was used to compare the SAS and SDS scores before and after treatment for each group. Two sample t-tests were used to compare cross-group differences. Chi-square tests were used to compare the proportions of patients with clinically significant anxiety or depression (i.e., those classified with mild, moderate or severe anxiety and depression based on SAS and SDS scores) between the two groups (standard two group chi-square tests) and over time (McNemar Tests,matched one-group chi-square tests).

3. Results

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, there were significant reductions in the overall severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in both treatment groups over the 8 weeks of treatment. This resulted in a substantial reduction in the proportion of patients who had clinically significant levels of anxiety or depression.There were, however, no statistically significant differences between the CBT group and medication group either before or after treatment.

In the CBT group 35 patients (55.6%) had comorbid depression and anxiety (i.e., SDS>53 and SAS>50) at the time of enrollment but only 2 patients (3.2%) had comorbid depression and anxiety after 8 weeks of treatment (χ2=31.03, p<0.001). In the medication group 36 patients (64.3%) had comorbid depression and anxiety at enrollment but only 3 (5.9%) had comorbid depression and anxiety after 8 weeks of treatment(χ2=31.03, p<0.001). There were no differences in theproportions of patients with comorbid depression and anxiety between the two groups at enrollment (χ2=0.94,p=0.333) or at the end of 8 weeks of treatment (χ2=0.35,p=0.554).

Table 1. Comparison of Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores before and after 8 weeks of treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or medication among patients with laryngectomy with depression or anxiety disorders

Table 2. Comparison of the proportion of patients with mild, moderate or severe ratings on the Self-ratingAnxiety Scale (SAS total score >50) and the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS total score >53)before and after 8 weeks of treatment with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) or medication

In the medication group 32% of the patients (18/56)had some adverse effect during the 8-week course of treatment: six had xerostomia, five had constipation,five had tremor, four had blurred vision, three had insomnia, one had both dizziness and headache, and one had nausea and vomiting. All of these symptoms were relieved after symptomatic treatment without requiring changes in the dosage or type of medication.

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

This study found that the SAS and SDS scores of postlaryngectomy patients who had distressing anxiety or depressive symptoms decreased significantly after 8 weeks of treatment with either CBT or symptom-specific medications and that the prevalence of anxiety disorder and depression (based on SAS and SDS cutoff scores)in the two treatment groups also dropped significantly.However, there was no statistically significant difference in the treatment efficacy of the two types of treatment.

The improvement with CBT conforms with the finding of a large meta-analysis that found CBT beneficial in the management of the anxiety and depression that frequently occur in cancer patients.[10]Our study confirms this result with a special group of cancer patients –those who are unable to talk due to a laryngectomy.This finding is consistent with other studies in China and abroad which demonstrate that CBT is a reliable method in treating anxiety and depression.[11,12]CBT helps cancer patients identify and correct their maladaptive thinking patterns and improve their perceptions of their illness.They subsequently use more adaptive behaviors to replace pessimistic avoidance, which eventually leads to improvements in mood.

A previous study in a general medical setting in a high-income country found that CBT was superior to diazepam in the treatment of anxiety and depression;[13]our failure to find a difference in the effectiveness of CBT and medication may be due to the different patient group or the different medications used in our study.

4.2 Limitations

This study is based on a retrospective analysis of clinical records, so assignment of patients to the two treatment conditions was not random, it was based on the stated preferences of the patients. We found no statistically significant differences in the characteristics of the patients in the two treatment groups but unobserved selection biases may have affected the results. CBT was provided by a single clinician and no formal assessment of the fidelity of the treatment provided was made. There was no ‘placebo’ control group so it is impossible to be certain that the dramatic improvement over time was the result of the treatments; though unlikely, the substantial improvement in depressive and anxiety symptoms could have simply been a ‘return to the mean’ after the psychological trauma of the laryngectomy. The stressors that cause anxiety and depression in cancer patients typically persist until their deaths, so studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to determine whether patients need ‘booster’sessions of CBT or need to continue on their antianxiety and antidepressant medications to sustain the improvements seen in the current study over an 8-week treatment period.

4.3 Implications

An increasing number of general physicians and oncologists are realizing the importance of psychological wellbeing to the quality of life, recovery and long-term survival of cancer patients. There is a clear biological link between psychological stress and the immune system: high levels of anxiety and depression suppress the immune system, decrease the pain threshold and heighten the risk of progression, relapse, and metastasis of tumors. Comorbid anxiety and depression are associated with an estimated 10 to 20% reduction in life expectancy of cancer patients.[14]There is now convincing evidence that effective treatment for anxiety and depression can improve the quality of life and increase the life expectancy of cancer patients.[15]Clinicians in all fields need to be more proactive in identifying anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with life-threatening or chronic medical conditions; the effective treatment of these psychological symptoms can substantially improve the quality of life of these patients and slow the progression of their primary medical condition.Relatively simple screening measures such as the SAS and SDS could be used in a variety of clinical settings to identify individuals who would should receive a more detailed psychological evaluation and, possibly,treatment.

CBT is a relatively simple, short-term psychotherapeutic method that is acceptable to most patients.Based on the premise that cognitive activities play an important role in the occurrence and development of common psychological disorders,[16]CBT corrects patients’ maladaptive cognitions, beliefs and behaviors and, thus, results in a gradual improvement in anxiety and depressive symptoms. CBT also has the advantage that it has few adverse reactions so it avoids the difficulties of giving psychoactive medications to elderly cancer patients who are often taking multiple other medications and are physiologically compromised.In most circumstances this should be the first-line treatment for cancer patients who are having clinically significant psychological symptoms related to the difficulties of adapting to their life-threatening illness.Our study shows that it is both acceptable and effective in patients who are unable to communicate orally but are otherwise aware and alert.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

Funding

There was no source of funding for this study.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the psychiatrists in the psychology department of the Third People’s Hospital for their help, and professor Yi Zhou for his support.

1. Jiang QJ. [Medical Psychology]. Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House; 2005. Chinese

2. Zhang HL, Chen RX. [Oncology Nursing]. Tianjin: Tianjin Science and Technology Press; 2000. Chinese

3. Palmer SL, Reddick WE, Gajjar A. Understanding the cognitive impact on children who are treated for medulloblastoma. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(9): 1040-1049.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsl056

4. Devine EC. Meta analysis of the effect of psychoeducational interventions on pain in adults with cancer. OncolNurs Forum. 2003;30(1): 75-89. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1188/03.ONF.75-89

5. Society of Psychiatry, Chinese Medical Association. [Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, 3rdedition (CCMD-3)].Shandong Province: Shangdong Science and Technology Publishing House; 2001. Chinese

6. Zhang MY. [Manual of Psychiatric Rating Scales]. Changsha:Hunan Science Press; 2003. Chinese

7. Wang XD, Wang XL, Ma H. [Updated Version of the Handbook of Mental Health Rating Scales]. Beijing: Editorial Office of the Journal of Chinese Mental Health; 1999. Chinese

8. Wang ZY, Xun YF. [Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS)].Shanghai Jing Shen Yi Xue. 1984: 71-72. Chinese

9. Tao M, Gao JF. [Reliability and validity of Self-rating Anxiety Scale-CR]. Zhongguo Shen Jing Jing Shen Ji Bing Za Zhi. 1994;20(5): 301-303. Chinese

10. Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feurerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analysis. Intl J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(1): 13-34.

11. Zhang B, Wang L. [Influence of cognitive—behavioral nursing intervention on improving anxiety and depression of patients after breast cancer surgery]. Zhongguo Yi Yao Dao Bao. 2012;9(35): 159-161. Chinese

12. Paykel ES. Cognitive therapy in relapse prevention in depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10: 131-136.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1461145706006912

13. Power KG, Simpson RJ, Swanson V, Wallace LA.Controlled comparison of pharmacological and psychological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(336): 289-294

14. Fisch M. Treatment of depression in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32: 105. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh011

15. Yang YX, Xiu LJ. [Clinical research about using traditional Chinese medicine to treat depression in cancer patients].Zhongguo Zhong Yi Yao Xin Xi Za Zhi. 2009;16(2): 103-105.Chinese

16. Creswell C, Hentges F, Parkinson M, Sheffield P, Willetts P,Cooper P. Feasibility of guided cognitive behaviour therapy(CBT) self-help for childhood anxiety disorders in primary care. Mental Health in Family Medicine. 2010;7(49): 257

2013-08-27; accepted: 2014-03-03)

Jing Chen obtained her bachelor’s degree in clinical medicine from the Yun Yang Medical School, Hubei Province in 2001. Since 2004, she has been working in the Geriatric Psychiatry Department of the Third People’s Hospital of Huzhou City as an attending doctor. Her main research interests are in geriatric psychology and stress disorders in elderly patients.

认知行为治疗和症状特异性药物治疗伴焦虑和抑郁的喉切除术后咽喉癌患者的回顾性比较

陈静,陈传成,支胜利

认知行为治疗,喉切除术,抑郁症,焦虑症

Background:Laryngectomy, a common treatment for laryngeal cancer, is a disabling operation that can induce tremendous stress, but little is known about how to alleviate the psychological effects of the operation.Aim:Compare the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and medication in treating anxiety and depression among throat cancer patients after laryngectomy.Methods:Review of medical records of the psychological outpatient clinic in the Third People’s Hospital of Huzhou City between March 2009 and May 2013 identified 63 patients with post-laryngectomy depression or anxiety disorders who

8 weeks of one-on-one treatment with CBT (in which patients responded in writing because they were unable to speak) and 56 patients who received 8 weeks of treatment with buspirone (n=11), sertraline (n=9) or both busipirone and sertraline (n=36). The treatment provided (CBT or medications) was based on the stated preference of the patient. The Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) were administered before and after treatment.Results:After 8 weeks of treatment the mean SAS and SDS scores had decreased significantly in both groups and the prevalence of clinically significant anxiety and depression (based on SAS and SDS cutoff scores) had dropped dramatically. There were, however, no significant differences between the two treatment methods.In the medication group 32% of participants experienced one or more adverse reactions during treatment,but none of these were severe enough to require withdrawal from treatment.Conclusions:CBT is an effective, short-term treatment for reducing the anxiety and depressive symptoms that often occur after an individual is diagnosed with cancer or treated for cancer. There is robust evidence that treatment of these psychological symptoms can improve both the quality of life and course of illness in cancer patients, so oncologists and other clinicians need to regularly screen patients with cancer and other chronic life-threatening conditions for anxiety and depression and, if present, actively promote the treatment of these symptoms. This study shows that CBT can be effective for cancer patients even when they are unable to speak.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2014.02.006

1Third People’s Hospital, Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China

2Otolaryngology Department, Central Hospital of Huzhou, Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China*correspondence: 781703956@qq.com

A full-text Chinese translation will be available at www.saponline.org on May 15, 2014.

背景:喉切除术是一种常见的治疗喉癌损伤性手术作,可导致巨大的压力,但如何能减轻手术带来的心理影响知道甚少。目标:比较认知行为治疗(CBT)与药物治疗对喉切除术后咽喉癌患者焦虑和抑郁症状的治疗效果。方法:回顾湖州市第三人民医院2009年3月至2013年5月心理门诊中喉切除术后患有抑郁症或焦虑症患者的病历,确定63例患者曾接受过8周一对一的CBT治疗(其中无法说话的患者以书面形式作出回应),以及56例患者曾接受过8周的盐酸丁螺环酮治疗(n=11)、舍曲林治疗(n=9)或两种药物联合治疗(n=36)。治疗的选择(CBT或药物)是根据病人的陈述偏好而定的。采用焦虑自评量表(SAS)和抑郁自评量表(SDS)分别评估治疗前后的焦虑和抑郁症状。结果:治疗8周后, 两组的SAS平均分和SDS平均分都明显下降,(根据焦虑自评量表和抑郁自评量表评分标准)伴有有焦虑或者抑郁症状患者的百分比也显著下降了。但是,两种治疗方法之间没有显著差异。药物治疗组32%的参患者在治疗过程出现一个或多个不良反应,但这些都没有严重到需要停药治疗。讨论:CBT是一种有效的、短期的治疗手段,可用于减少一个人被诊断患有癌症或接受癌症治疗后往往产生的焦虑和抑郁症状。众多证据表明,这些心理症状的治疗可以提高癌症患者的生活质量和减短疾病的病程,所以肿瘤学家和其他临床医生需要定期筛查癌症患者和其他危及生命的慢性病患者的抑郁和焦虑症状,如果存在的话,就需要积极对这些症状进行治疗。这项研究表明,CBT对于即使无法说话的癌症患者来说也是有效的。

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- The dopamine system and alcohol dependence

- Suicide in India: a systematic review

- Effectiveness of self-management training in community residents with chronic schizophrenia: a single-blind randomized controlled trial in Shanghai, China

- Randomized controlled trial comparing changes in serum prolactin and weight among female patients with first-episode schizophrenia over 12 months of treatment with risperidone or quetiapine

- Providing free treatment for severe mental disorders in China

- Case report on lithium intoxication with normal lithium blood levels