2q35 rs13387042和8q24 rs13281615单核苷酸多态性与中国东北汉族绝经前妇女乳腺癌风险关系

哈尔滨医科大学附属第三医院乳腺外科,黑龙江 哈尔滨 150086

2q35 rs13387042和8q24 rs13281615单核苷酸多态性与中国东北汉族绝经前妇女乳腺癌风险关系

白夏楠 姜永冬 刘通 吴昊 张金锋 庞达

哈尔滨医科大学附属第三医院乳腺外科,黑龙江 哈尔滨 150086

背景与目的:乳腺癌作为中国女性最常见的恶性肿瘤,每年的新发数量和死亡数量分别占全世界的12.2%和9.6%,但与中国乳腺癌患者明显相关的基因多态位点至今尚不清楚。本研究旨在探讨2q35 rs13387042和8q24 rs13281615单核苷酸多态性与中国北方汉族绝经前妇女乳腺癌风险关系,为预防和治疗乳腺癌提供循证依据。方法:采用多重单碱基延伸单核苷酸多态性分型技术(SNaPshot)分析方法,检测了280例绝经前乳腺癌患者和287例绝经前正常对照者2q35 rs13387042和8q24 rs13281615多态性位点基因型,并比较不同基因型和等位基因与乳腺癌风险的关系。结果:2q35 rs13387042多态性位点基因型频率在乳腺癌和对照样本之间差异有统计学意义(P=0.017);8q24 rs13281615多态性位点基因型频率在乳腺癌和对照样本之间差异无统计学意义(P=0.967)。Logistic回归分析结果显示,对于2q35 rs13387042位点,与GG相比,GA和GA+AA基因型携带者显著增加乳腺癌的患病风险(OR=1.793,95%CI:1.177~2.733,P=0.007;OR=1.691,95%CI:1.122~2.550,P=0.012),而AA携带者与乳腺癌的患病风险无关(OR=0.572,95%CI:0.104~3.153,P=0.521);与G等位基因相比,A等位基因显著增加乳腺癌的患病风险(OR=1.505,95%CI:1.033~2.193,P=0.033)。对于8q24 rs13281615位点,与AA相比,AG、GG和AG+GG基因型携带者与乳腺癌的患病风险无关(OR=0.992,95%CI:0.660~1.490,P=0.968;OR=1.047,95%CI:0.642~1.708,P=0.853;OR=1.007,95%CI:0.682~1.487,P=0.971);与A等位基因相比,G等位基因不增加乳腺癌患病风险(OR=1.021,95%CI:0.809~1.288,P=0.863)。结论:本实验证实2q35 rs13387042多态性位点能够增加中国北方汉族绝经前妇女乳腺癌易感风险,而8q24 rs13281615多态性位点与中国北方汉族绝经前妇女乳腺癌易感性无明显相关性。

乳腺肿瘤;单核苷酸多态;遗传易感性;2q35 rs13387042;8q24 rs13281615

乳腺癌是女性最常见的恶性肿瘤之一,在发展中国家和发达国家中都是女性死亡的首要原因[1]。乳腺癌发病率在世界范围内明显上升,并且发病年龄有年轻化趋势[2]。中国乳腺癌发病率增长速度是全球的两倍多[3],2010年中国女性乳腺癌新发病例约21万,居所有恶性肿瘤发病率的首位[4]。据估计,每年超过100万的妇女被诊断为乳腺癌,超过41万死于乳腺癌[5]。乳腺癌的病因十分复杂,具体机制尚未阐明,普遍认为是遗传、内分泌和外部环境多因素相互作用的结果[6]。BRCA1、BRCA2等高外显率基因被认为与家族性乳腺癌相关[7],但大多数乳腺癌的发生很可能与更多的低外显率基因多态性有关[8]。近年来通过全基因组关联研究(genome-wide association studies,GWAS)发现了许多乳腺癌易感基因位点[9-12],其中2q35 rs13387042和8q24 rs13281615就是通过此技术筛选出来的基因变异位点[9,13]。由于人种和地域的差异,各研究中心对于这2个位点是否与乳腺癌风险相关的结论不完全一致[9,13-18]。本研究旨在探讨2q35 rs13387042和8q24 rs13281615位点遗传多态性与我国北方汉族绝经前妇女乳腺癌的风险关系。

1 对象和方法

1.1 研究对象

选择2008年11月—2009年5月,在哈尔滨医科大学附属第三医院乳腺外科经组织病理学确诊的汉族绝经前女性原发性乳腺癌患者,除乳腺癌外无其他肿瘤患病史,无肿瘤家族史,术前未行放、化疗,共280例(病例组),平均年龄(42.8±5.8)岁。健康对照者为2009年3—8月在哈尔滨医科大学附属第二医院体检中心健康普查体检合格的汉族绝经前妇女,无恶性肿瘤和乳腺疾病患病史,无肿瘤家族史,共287例(对照组),平均年龄(42.4±5.8)岁。研究对象需签署知情同意书,并完成流行病学调查和提供血液标本。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 基因组DNA提取

抽取乳腺癌患者及健康对照者的外周血2 mL,以EDTA抗凝,采用爱思进公司DNA提取试剂盒提取基因组DNA,-80 ℃保存。

1.2.2 PCR及测序鉴定基因型

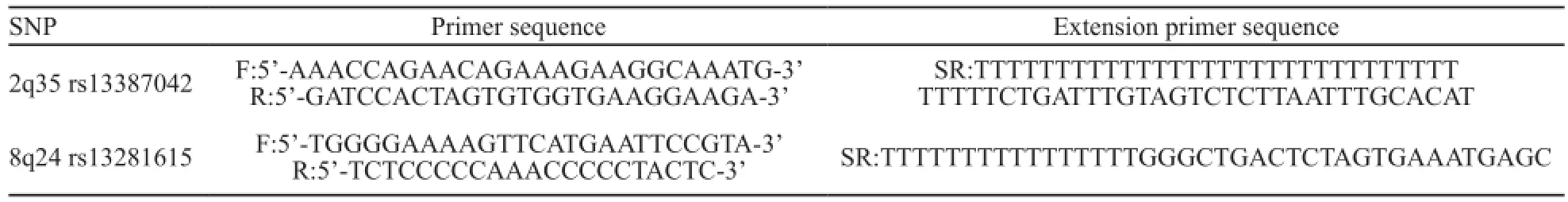

采用多重单碱基延伸单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphism,SNP)分型技术(SNaPshot)对2个SNP位点进行分型。设计2对PCR引物用于扩增,包含2个SNP位点的片段,同时设计了2条紧邻SNP位点的延伸引物(表1)用于SNaPshot多重单碱基延伸。PCR反应:PCR反应体系(共20 μL)包含1×HotStarTaq buffer,3.0 mmol/L Mg2+,0.3 mmol/L dNTP,每对引物0.1 μmol/L,1 U HotStarTaq polymerase (购自美国Qiagen公司)和1 μL样本DNA。PCR循环程序采用touch-down PCR反应程序:95 ℃预变性15 min后,94 ℃变性20 s,65 ℃退火40 s (每个循环退火温度降低0.5 ℃),72 ℃延伸1.5 min,共11个循环。然后94 ℃变性20 s,59 ℃退火30 s,72 ℃延伸1.5 min,共24个循环;72 ℃终延伸2 min,最后4 ℃保存产物。PCR产物纯化按操作说明步骤采用SAP/ExoⅠ(购自美国ABI公司)酶法:在10 μL PCR产物中加入1 U SAP酶和1 U Exonuclease Ⅰ酶,37 ℃温浴1 h后,75 ℃灭活15 min。SNaPshot多重单碱基延伸反应:PCR产物经纯化后用SNaPshot Multiplex试剂盒(购自美国ABI公司)进行延伸反应鉴定基因型。延伸反应体系(10 μL)包括5 μL SNaPshot Multiplex Kit(购自美国ABI公司),2 μL纯化后多重PCR产物,1 μL延伸引物混合物(每个延伸引物0.8 mmol/L),2 μL超纯水。PCR循环程序:96 ℃预变性1 min;96 ℃变性10 s,50 ℃退火5 s,60 ℃延伸30 s,共进行28个循环,最后保存在4 ℃。延伸产物纯化:在10 μL延伸产物中加入1 U SAP酶37 ℃温浴1 h,然后75 ℃灭活15 min。取0.5 μL纯化后的延伸产物,与0.5 μL内标Liz120 (购自美国ABI公司),9 μL甲酰胺混匀,95 ℃变性5 min后上ABI 3130XL测序仪进行毛细管电泳;运行GeneMapper 4.0软件(购自美国ABI公司)分析实验结果。

1.3 统计学处理

采用SPSS 13.0统计软件对数据进行统计分析,以χ2检验比较各基因型在病例组与对照组之间分布的差异。采用Logistic回归分析计算比数比(OR)及其95%置信区间(CI)来评估各基因型和乳腺癌风险之间的相关性。全部的显著性检验均为双侧概率检验,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 2q35 rs13387042基因型频率和等位基因频率分布及与乳腺癌易感性的关系

在对照组中,2q35 rs13387042位点的GG、 GA和AA基因型频率分别为83.3%、15.3%和1.4%,在病例组中分别为74.6%、24.6%和0.71%。2q35 rs13387042基因型在对照组和病例组的分布均符合Hardy-Weinberg平衡定律(P=0.239)。病例组和对照组3种基因型频率分布差异有统计学意义(P=0.017)。

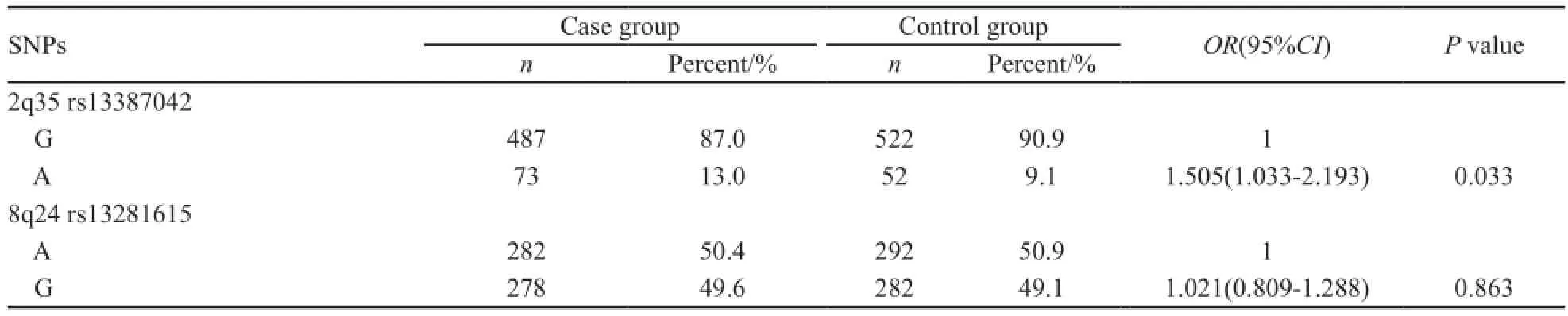

L o g i s t i c回归分析结果显示,2 q 3 5 rs13387042位点在共显性模型下,与野生纯合型GG携带者相比,GA杂合型携带者与乳腺癌患病风险显著相关(OR=1.793,95%CI:1.177~2.733,P=0.007),而突变纯合型AA携带者与乳腺癌的患病风险无关(OR=0.572,95%CI:0.104~3.153,P=0.521);在显性模型下,Logistic回归分析结果显示,与GG基因型携带者相比,GA+AA基因型携带者与乳腺癌的患病风险显著相关(OR=1.691,95%CI:1.122~2.550,P=0.012)。同时,与G等位基因相比,A等位基因显著增加乳腺癌患病风险(OR=1.505,95%CI:1.033~2.193,P=0.033,表2,、3)。

2.2 8q24 rs13281615基因型频率和等位基因频率分布及与乳腺癌易感性的关系

在对照组中,8q24 rs13281615位点的AA、AG和GG基因型频率分别为23.3%、55.1%和21.6%,在病例组中分别为23.2%、54.3%和22.5%。8q24 rs13281615基因型在对照组和病例组的分布均符合Hardy-Weinberg平衡定律(P=0.086)。病例组和对照组3种基因型频率分布差异无统计学意义(P=0.967)。

L o g i s t i c回归分析结果显示,8 q 2 4 rs13281615位点在共显性模型下,与野生纯合型AA携带者相比,AG杂合型携带者和突变纯合型GG携带者与乳腺癌的患病风险无关(OR=0.992,95%CI:0.660~1.490,P=0.968;OR=1.047,95%CI:0.642~1.708,P=0.853);在显性模型下,Logistic回归分析结果显示,与AA基因型携带者相比,AG+GG基因型携带者与乳腺癌的患病风险无关(OR=1.007,95%CI:0.682~1.487,P=0.971)。同时,与A等位基因相比,G等位基因与乳腺癌患病风险无显著相关性(OR=1.021,95%CI:0.809~1.288,P=0.863,表2、3)。

表1 相关SNP位点PCR引物及延伸引物序列信息Tab. 1 PCR primers and extension primers sequence information of relevant SNP loci

表2 2q35 rs13387042、8q24 rs13281615位点基因型频率在病例组和对照组的分布Tab. 2 The distribution of 2q35 rs13387042, 8q24 rs13281615 genotype frequency in cases and controls

表3 2q35 rs13387042、8q24 rs13281615位点等位基因频率在病例组和对照组的分布Tab. 3 The distribution of 2q35 rs13387042, 8q24 rs13281615 allele frequency in cases and controls

3 讨 论

乳腺癌是世界范围内女性最常见的恶性肿瘤之一,是一种遗传因素发挥重要作用的复杂多基因疾病[19-20]。其中,15%~25%家族性乳腺癌的患病风险被认为与乳腺癌易感基因BRCA1和BRCA2相关[19,21];然而,大部分乳腺癌患病风险的遗传成分仍然未知,低外显率变异体联合作用在这方面起到关键作用[22-23]。目前,已经报告的与乳腺癌患病风险相关的常见低外显率遗传变异体有40多种[24]。2q35 rs13387042和8q24 rs13281615多态性位点就是其中研究较多的乳腺癌易感位点,其与乳腺癌的关系近年来得到广泛关注。

SNP 2q35 rs13387042(A>G)位于高连锁不平衡的90 kb区,该区域包含了未知基因以及非编码 RNAs[25]。2007年,Stacey等[13]首先通过对1 600例冰岛妇女进行GWAS筛查首先发现了2q35 rs13387042多态位点,进一步病例对照研究发现2q35 rs13387042 A等位基因增加欧洲人中ER(+)乳腺癌患病风险(P=4.3×10-9)。随后,Milne等[26]综合分析了31 510例浸润性乳腺癌、1 101例导管原位癌和35 969例正常女性的25项研究数据,证实了rs13387042与欧洲裔白人妇女乳腺癌发生显著相关,并且这种关联在ER(+)(OR=1.14,95%CI:1.10~1.17,P=1×10-15)和ER(-)(OR=1.10,95%CI:1.04~1.15,P=0.000 3)以及PR(+)(OR=1.15,95%CI:1.11~1.19,P=5×10-14)和PR(-)(OR=1.10,95%CI:1.06~1.15,P=0.000 02)乳腺癌中都存在,但在ER(+)和PR(+)乳腺癌中略强。2q35 rs13387042多态性也被证实与中国、美国和中国台湾等地区妇女的乳腺癌患病率相关[17,27-29]。然而,Kim等[30]和Sueta等[31]分别对汉城和日本妇女进行病例对照研究,并未发现2q35 rs13387042多态性位点与乳腺癌患病风险相关。由于月经状态影响肿瘤的激素水平,Sueta等[31]发现乳腺癌患病风险的遗传风险评分及这种风险对绝经前患者起的作用比绝经后患者明显。在他们的研究中,ER+/PR+肿瘤在绝经前乳腺癌患者中所占比例比绝经后高(71.0% vs 48.7%)。结果不一致可能与研究者没有依据月经状态对研究对象进行分类有关。因此,我们对中国北方绝经前女性进行病例对照研究,结果显示2q35 rs13387042 SNP基因型频率和等位基因频率在病例组和对照组中分布存在显著差异,A等位基因显著增加乳腺癌患病风险。此外,不同种族中2q35 rs13387042多态位点等位基因的分布不同也会导致结果出现差异。例如,我们前期研究结果显示A风险等位基因在中国北方妇女中分布频率约为11%[32],与本次实验结果相符;而其在白人[13-14,33]和非洲后裔[16,27,34]中的频率分别为51%和72%。并且,在不同种族人群中,2q35 rs13387042多态位点可与附近因果变异体形成紧密连锁。其他如实验设计,样本量较小和一些环境因素也会影响实验结果。

8q24 rs13281615位点位于染色体8q24的非基因区域,其功能尚不十分清楚。8q24.12~24.13位置上有髓细胞增生原癌基因(myelocytomatosis oncogene,MYC),此基因在正常细胞中不表达,在一部分癌细胞中表达,可促进细胞增殖、永生化、去分化和转化等,MYC表达失调并与染色体8q24易感位点相互作用是促进包括乳腺癌在内多种肿瘤发生的重要因素[35]。2007年,Easton等[9]通过3个阶段的GWAS筛选首先发现8q24 rs13281615显著增加乳腺癌患病风险(P<1×10-7),并且与家族性乳腺癌相关(OR=1.06,95 %CI:1.00~1.12,P=0.05)。Fletcher等[14]对1 499例乳腺癌患者和1 390例健康对照者进行病例对照研究,进一步证实8q24 rs13281615 AG基因型(OR=1.30,95%CI:1.09~1.54)和GG基因型(OR=1.52,95%CI:1.22~1.89)显著增加英格兰和苏格兰人罹患乳腺癌的风险(P=0.000 03)。Tamimi等[36]发现8q24 rs13281615同样增加瑞典人的乳腺癌患病风险,并且出生体质量越高这种作用越明显,他们认为这可能与出生体质量高的妇女携带更大的乳腺干细胞库有关。然而,本次病例对照研究结果显示,对于8q24 rs13281615位点,与AA携带者相比,AG携带者、GG携带者和AG+GG基因型携带者与乳腺癌的患病风险无关。与此结论相一致,8q24 rs13281615多态性也被证实与智利、突尼斯、俄罗斯和非裔美洲等地区妇女的乳腺癌患病风险无显著关联[27,37-40]。对中国其他地区女性的研究也未发现此位点增加乳腺癌患病风险[28,32,41]。然而,李莉华等[42]对中国妇女进行分层研究发现,G等位基因或AG和GG基因型增加中国汉族女性50岁以前患乳腺癌的风险,但与50岁以后女性乳腺癌风险无显著关联。Garcia-Closas等[43]和Zhang等[44]对欧洲和亚洲人进行病例对照研究发现,8q24 rs13281615显著增加ER(+)/PR(+)乳腺癌患病风险。由此推断,对8q24 rs13281615多态性是否与乳腺癌发病风险有关的研究结果不同,可能与研究者未按月经状态对研究对象进行分层研究有关。此外,8q24 rs13281615多态性位点等位基因分布频率在各种族间存在显著差异也可以解释研究结论的不同。例如,在欧洲群体中,8q24 rs13281615 A为优势等位基因(54%)[14];然而,在智利群体中,8q24 rs13281615 G为优势等位基因(56%)[37]。本次对中国北方汉族绝经前女性的研究分析发现8q24 rs13281615 A为优势等位基因,其在病例组和对照组中的频率分别为50.4%和50.9%。

综上所述,考虑到月经状态对乳腺癌患病风险的影响,我们选择绝经前妇女作为研究对象。结果显示2q35 rs13387042位点与中国北方汉族绝经前妇女乳腺癌发病风险显著相关;8q24 rs13281615位点与中国北方汉族绝经前妇女乳腺癌发病风险不相关。不同国家人群由于遗传因素及生活方式不同,其研究结果可能不同;单独2个易感位点对最终致癌效果的影响有限,尚需要联合其他易感位点进行多中心多种族的大样本分层研究。2q35 rs13387042和8q24 rs13281615多态性与乳腺癌风险的深入研究可为乳腺癌病因提供新的线索,为乳腺癌的分子诊断提供新的标志物,以此为治疗靶点开发新药物将会使部分乳腺癌患者受益。

[1] SHULMAN L N, WILLETT W, SIEVERS A, et al. Breast cancer in developing countries: opportunities for improved survival[J]. J oncol, 2010, 2010: 595167.

[2] ENSERINK M. A push to fight cancer in the developing world[J]. Science, 2011, 331(6024): 1548-1550.

[3] FAN L, ZHENG Y, YU K D, et al. Breast cancer in a transitional society over 18 years: trends and present status in Shanghai, China[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2009, 117(2): 409-416.

[4] 陈万青, 张思维, 曾红梅, 等. 中国2010年恶性肿瘤发病与死亡[J]. 中国肿瘤, 2014, 23(1): 1-10.

[5] COUGHLIN S S, EKEUEME D U. Breast cancer as a global health concern[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2009, 33(5): 315-318.

[6] LICHTENSTEIN P, HOLM N V, VERKASALO P K, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland[J]. N Engl J Med, 2000, 343(2): 78-85.

[7] WALSH T, CASADEI S, COATS K H, et al. Spectrum of mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, and TP53 in families at high risk of breast cancer[J]. JAMA, 2006, 295(12): 1379-1388.

[8] ANTONIOU A C, EASTON D F. Models of genetic susceptibility to breast cancer[J]. Oncogene, 2006, 25(43): 5898-5905.

[9] EASTON D F, POOLEY K A, DUNNING A M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci[J]. Nature, 2007, 447(7148): 1087-1093.

[10] HUNTER D J, KRAFT P, JACOBS K B, et al. A genomewide association study identifies alleles in FGFR2 associated with risk of sporadic postmenopausal breast cancer[J]. Nat Genet, 2007, 39(7): 870-874.

[11] ZHENG W, LONG J, GAO Y T, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new breast cancer susceptibility locus at 6q25. 1[J]. Nat Genet, 2009, 41(3): 324-328.

[12] THOMAS G, JACOBS K B, KRAFT P, et al. A multistage genome-wide association study in breast cancer identifies two new risk alleles at 1p11. 2 and 14q24. 1 (RAD51L1)[J]. Nat Genet, 2009, 41(5): 579-584.

[13] STACEY S N, MANOLESCU A, SULEM P, et al. Common variants on chromosomes 2q35 and 16q12 confer susceptibility to estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer[J]. Nat Genet, 2007, 39(7): 865-869.

[14] FLETCHER O, JOHNSON N, ORR N, et al. Novel breast cancer susceptibility locus at 9q31. 2: results of a genomewide association study[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2011, 103(5): 425-435.

[15] ZHENG W, WEN W, GAO Y T, et al. Genetic and clinical predictors for breast cancer risk assessment and stratification among Chinese women[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2010, 102(13): 972-981.

[16] HUTTER C M, YOUNG A M, OCHS-BALCOM HM, et al. Replication of breast cancer GWAS susceptibility loci in the Women’s Health Initiative African American SHARe Study[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2011, 20(9): 1950-1959.

[17] SLATTERY M L, BAUMGARTNER K B, GIULIANO A R, et al. Replication of five GWAS-identified loci and breast cancer risk among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women living in the Southwestern United States[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2011, 129(2): 531-539.

[18] CAMPA D, KAAKS R, LE Marchand L, et al. Interactions between genetic variants and breast cancer risk factors in the breast and prostate cancer cohort consortium[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2011, 103(16): 1252-1263.

[19] BALMAIN A, GRAY J, PONDER B. The genetics and genomics of cancer[J]. Nat Genet, 2003, 33(Suppl): 238-244.

[20] NATHANSON K L, WOOSTER R, WEBER B L. Breast cancer genetics: what we know and what we need[J]. Nat Med, 2001, 7(5): 552-556.

[21] EASTON D F. How many more breast cancer predisposition genes are there?[J]. Breast Cancer Res, 1999, 1(1): 14-17.

[22] PHAROAH P D, ANTONIOU A, BOBROW M, et al. Polygenic susceptibility to breast cancer and implications for prevention[J]. Nat Genet, 2002, 31(1): 33-36.

[23] PHAROAH P D, ANTONIOU A C, EASTON D F, et al. Polygenes, risk prediction, and targeted prevention of breast cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 358(26): 2796-2803.

[24] HINDORFF L A, SETHUPATHY P, JUNKINS H A, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009, 106(23): 9362-9367.

[25] OHMIYA N, TAGUCHI A, MABUCHI N, et al. MDM2 promoter polymorphism is associated with both an increased susceptibility to gastric carcinoma and poor prognosis[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2006, 24(27): 4434-4440.

[26] MILNE R L, BENITEZ J, NEVANLINNA H et al. Risk of estrogen receptor-positive and -negative breast cancer and single-nucleotide polymorphism 2q35-rs13387042[J]. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2009, 101(14): 1012-1018.

[27] ZHENG W, CAI Q, SIGNORELLO L B, et al. Evaluation of 11 breast cancer susceptibility loci in African-American women[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2009, 18(10): 2761-2764.

[28] DAI J, HU Z, JIANG Y, et al. Breast cancer risk assessment with five independent genetic variants and two risk factors in Chinese women[J]. Breast Cancer Res, 2012, 14(1): R17.

[29] LIN C Y, HO C M, BAU D T, et al. Evaluation of breast cancer susceptibility loci on 2q35, 3p24, 17q23 and FGFR2 genes in Taiwanese women with breast cancer[J]. Anticancer Res, 2012, 32(2): 475-482.

[30] KIM H C, LEE J Y, SUNG H, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies a breast cancer risk variant in ERBB4 at 2q34: results from the Seoul Breast Cancer Study[J]. Breast Cancer Res, 2012, 14(2): R56.

[31] SUETA A, ITO H, KAWASE T, et al. A genetic risk predictor for breast cancer using a combination of low-penetrance polymorphisms in a Japanese population[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2012, 132(2): 711-721.

[32] JIANG Y, HAN J, LIU J, et al. Risk of genome-wide association study newly identified genetic variants for breast cancer in Chinese women of Heilongjiang Province[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2011, 128(1): 251-257.

[33] REEVES G K, TRAVIS R C, GREEN J, et al. Incidence of breast cancer and its subtypes in relation to individual and multiple low-penetrance genetic susceptibility loci[J]. JAMA, 2010, 304(4): 426-434.

[34] CHEN F, CHEN G K, MILLIKAN R C, et al. Fine-mapping of breast cancer susceptibility loci characterizes genetic risk in African Americans[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2011, 20(22): 4491-4503.

[35] AHMADIYEH N, POMERANTZ M M, GRISANZIO C, et al. 8q24 prostate, breast, and colon cancer risk loci show tissuespecific long-range interaction with MYC[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010, 107(21): 9742-9746.

[36] TAMIMI R M, LAGIOU P, CZENE K, et al. Birth weight, breast cancer susceptibility loci, and breast cancer risk[J]. Cancer Causes Control, 2010, 21(5): 689-696.

[37] ELEMATORE I, GONZALEZ-HORMAZABAL P, REYES J M, et al. Association of genetic variants at TOX3, 2q35 and 8q24 with the risk of familial and early-onset breast cancer in a South-American population[J]. Mol Biol Rep, 2014, 41(6): 3715-3722.

[38] GORODNOVA T V, KULIGINA E, YANUS G A, et al. Distribution of FGFR2, TNRC9, MAP3K1, LSP1, and 8q24 alleles in genetically enriched breast cancer patients versus elderly tumor-free women[J]. Cancer Genet Cytogenet, 2010, 199(1): 69-72.

[39] HUO D, ZHENG Y, OGUNDIRAN T O, et al. Evaluation of 19 susceptibility loci of breast cancer in women of African ancestry[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2012, 33(4): 835-840.

[40] SHAN J, MAHFOUDH W, DSOUZA S P, et al. Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) breast cancer susceptibility loci in Arabs: susceptibility and prognostic implications in Tunisians[J]. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2012, 135(3): 715-724.

[41] LONG J, SHU X O, CAI Q, et al. Evaluation of breast cancer susceptibility loci in Chinese women[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2010, 19(9): 2357-2365.

[42] 李莉华, 郭子健, 华东, 等. 8q24 rs13281615基因多态性与中国汉族女性乳腺癌患病风险及临床病理特征的关系[J]. 中华检验医学杂志 2011, 34(1): 73-76.

[43] GARCIA-CLOSAS M, HALL P, Nevanlinna H et al. Heterogeneity of breast cancer associations with five susceptibility loci by clinical and pathological characteristics[J]. PLoS Genet, 2008, 4(4): e1000054.

[44] ZHANG Y, YI P, CHEN W et al. Association between polymorphisms within the susceptibility region 8q24 and breast cancer in a Chinese population[J]. Tumour Biol, 2014, 35(3): 2649-2654.

Relationship between single nucleotide polymorphisms in 2q35 rs13387042 and 8q24 rs13281615 and breast cancer risk of Han premenopausal women in Northern China

BAI Xia-nan, JIANG Yong-dong,

LIU Tong, WU Hao, ZHANG Jin-feng, PANG Da

(Department of Breast Surgery of the Third Af fi liated Hospital, Harbin Medical University, Harbin Heilongjiang 150086, China)

PANG Da E-mail: pangdasir@163.com

Background and purpose: Breast cancer as one of the most common malignant tumor among women in China, it accounts for 12.2% of all newly diagnosed breast cancers and 9.6% of all deaths from breast cancer worldwide. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between single nucleotide polymorphisms(SNPs) in 2q35 rs13387042 and 8q24 rs13281615 and the risk of breast cancer in Han premenopausal women of Northern China. Methods: 280 patients with breast cancer and 287 healthy controls in premenopausal state were genotyped for SNP 2q35 rs13387042 and 8q24 rs13281615 by the SNaPshot method, and compared the different genotypes and alleles with relation to breast cancer risk. Results: Differences of 2q35 rs13387042 genotype frequencies between breast cancer and control were signi fi cantly different (P=0.017). No statistically signi fi cant difference of 8q24 rs13281615 genotype frequencies between breast cancers and controls was found (P=0.967). The results of logistic regression showed thatthe carriers of GA genotype and GA+ AA genotype increased risk for breast cancer compared to the carriers with 2q35 rs13387042 GG genotype(OR=1.793, 95%CI: 1.177-2.733, P=0.007;OR=1.691, 95%CI: 1.122-2.550, P=0.012), but not the carriers of AA genotype; Compared with G allele, A allele signi fi cantly increased the risk of breast cancer(OR= 1.505, 95%CI: 1.033-2.193, P=0.033). The carriers of AG genotype or GG genotype or AG+GG genotype did not confer risk for breast cancer compared to the carriers with 8q24 rs13281615 AA genotype(OR=0.992, 95%CI: 0.660-1.490, P=0.968; OR=1.047, 95%CI: 0.642-1.708, P=0.853; OR=1.007, 95%CI: 0.682-1.487, P=0.971); Compared with A allele, G allele did not increase the risk of breast cancer(OR=1.021, 95%CI: 0.809-1.288, P=0.863). Conclusion: This experiment veri fi ed that 2q35 rs13387042 polymorphism site increased risk of breast cancer susceptibility among Han premenopausal women of Northern China. There was not any signi fi cant association between 8q24 rs13281615 polymorphism site and breast cancer susceptibility among Han premenopausal women of Northern China under the current sampling scale.

Breast neoplasms; Single nucleotide polymorphism; Genetic susceptibility; 2q35 rs13387042; 8q24 rs13281615

10.3969/j.issn.1007-3969.2014.09.005

R737.9

A

1007-3639(2014)09-0669-07

2014-06-02

2014-08-21)

庞达 E-mail:pangdasir@163.com