Barefoot running survey:Evidence from the field

Dvid Hryvnik,Jy Dichrry,Roert Wilder

aPhysical Medicine and Rehabilitation,University of Virginia,Charlottesville,VA 22908,USA

bRebound Physical Therapy,Bend,OR 97701,USA

Barefoot running survey:Evidence from the field

David Hryvniaka,*,Jay Dicharryb,Robert Wildera

aPhysical Medicine and Rehabilitation,University of Virginia,Charlottesville,VA 22908,USA

bRebound Physical Therapy,Bend,OR 97701,USA

Background:Running is becom ing an increasingly popular activity among Americans w ith over 50 m illion participants.Running shoe research and technology has continued to advance w ith no decrease in overall running injury rates.A grow ing group of runners are making the choice to try the m inimal or barefoot running styles of the pre-modern running shoe era.There is some evidence of decreased forces and torques on the lower extrem ities w ith barefoot running,butno clear data regarding how this corresponds w ith injuries.The purpose of this survey study was to exam ine factors related to performance and injury in runners who have tried barefoot running.

Methods:The University of Virginia Center for Endurance Sport created a 10-question survey regarding barefoot running that was posted on a variety of running blogs and Facebook pages.Percentages were calculated for each question across all surveys.Five hundred and nine participants responded w ith over 93%of them incorporating some type of barefoot running into their weekly m ileage.

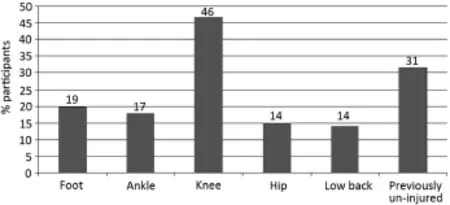

Results:A majority of the participants(53%)viewed barefoot running as a training tool to improve specific aspects of their running.However, close to half(46%)viewed barefoot training as a viable alternative to shoes for logging their m iles.A large portion of runners initially tried barefoot running due to the promise of improved efficiency(60%),an attempt to getpast injury(53%)and/or the recentmedia hype around the practice(52%).A large majority(68%)of runners participating in the study experienced no new injuries after starting barefoot running.In fact, most respondents(69%)actually had their previous injuries go away after starting barefoot running.Runners responded that their previous knee (46%),foot(19%),ankle(17%),hip(14%),and low back(14%)injuries all proceeded to improve after starting barefoot running.

Conclusion:Prior studies have found that barefoot running often changes biomechanics compared to shod running w ith a hypothesized relationship of decreased injuries.This paper reports the resultof a survey of 509 runners.The results suggest thata large percentage of this sample of runners experienced benefi ts or no serious harm from transitioning to barefoot or minimal shoe running.

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

Barefoot;Biomechanics;Injuries;Running;Survey

1.Introduction

Running is becoming an increasingly popular activity among Americans w ith over 50 m illion participants.This represents a grow th ofalmost8%in 1 yearand a 57%increase in the last10 years.1More people are running either for fi tness or performance w ith almost 14 million US road race participants in 2011,a 7%increase from the year prior.A ll these runners are creating a huge market for running gear as running shoe sales topped 2.46 billion dollars in 2011 w ith over 65% of runners spending more than 90 dollars on their running shoes.1Running shoes have become increasingly more expensive w ith more technology and research behind the design of modern running shoes.However,running injuries appear to be justas prevalentas they always have been w ith an estimated 30%—75% of average recreational runners becoming injured at leastonce each year.2,3Despite increasingmoney and technology invested into shoe design,there has yet to be a decrease in running injury rates per capita.2

Humans have run m inimally shod or barefoot for m illions of years,but only recently has the running shoe become an essential part of a runner’s gear.4Furthermore,there is little evidence to support the currentpractice of prescribing elevated running shoes w ith cushioned heels and pronation control systems to prevent injuries.5Currently,there is an increasing trend in the running community to revert back to the premodern shoe era w ith m inimalist or barefoot running.This grow ing barefoot running movementhas resulted in significant attention given in the national press.

W ith this recent focus,health care practitioners are inundated w ith questions regarding the safety and implementation of these programs.A cautious outlook on new trends,and an education heavily biased from the shoe industry itself,has made most clinicians reluctant to embrace alternative thinking regarding footwear needs.In fact,much resistance has been made by the clinical community w ith case studies that document the occasional injury.These injuries have likely been related to improper transitioning when loads on the body are increased faster than their rate of repair.Although multiple studies have shown decreased lower extrem ity joint torques and peak impact forces w ith barefoot running as compared to shod running,6—8there are no data on barefoot or minimal footwear running injuries.Therefore,the purpose of this survey study was to provide outcome data regarding the effects of barefoot running on efficiency,performance,and injury.

2.M ethods

The University of Virginia Center for Endurance Sport created a 10-question survey completed by 509 runners.This survey was approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board.The authors developed the list of questions based on importance to runners.The authors inquired whether the runners had tried barefoot running,if it made a difference in their running,and whether they instituted as part of their normal training plan.If so,the authors then inquired whether barefoot running played a role in injury and performance.The specific questions posed to participants are provided in Results section as well as in Figs.1—10.The survey was released through the University of Virginia Speed clinic,its blog,and its Facebook site.Additionally,several other blogs advertised the study.To be included,runners had to have tried barefoot running and had enough experience w ith barefoot running to be able to successfully answer all 10 questions,regardless of whether they were still barefoot running.We did notwant to restrict the survey to runners who had successfully transitioned,as we felt it m ight have biased the results.

3.Results

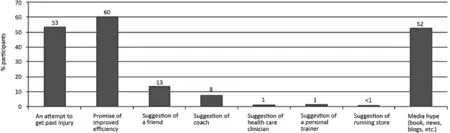

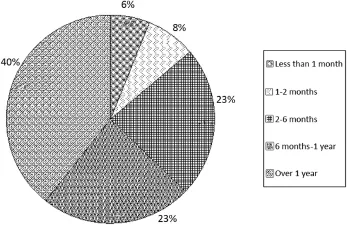

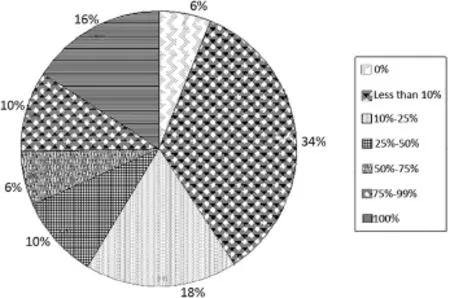

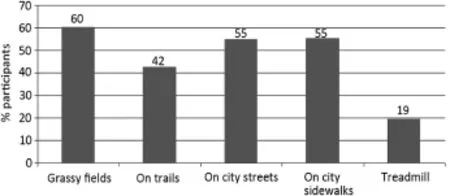

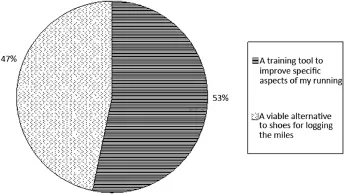

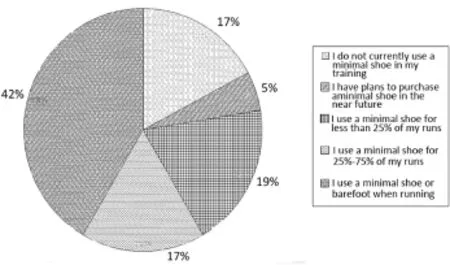

The study included 509 participants who had some experience w ith barefoot running.A large portion of runners initially tried barefoot running due to the prom ise of improved efficiency(60%),an attempt to get past injury(53%)and/or the recentmedia hype around the practice(52%)(Fig.1).Only a small percentage of runners started barefoot running at the suggestion of a friend(13%),coach(8%),health care clinician (1%),personal trainer(1%),or running store(<1%).A majority(40%)had been running barefoot for greater than 1 year, w ith 23%of respondents between 6 months and 1 year,and 23%for 2—6 months.Only 6%of runners who partook in the survey had tried barefoot running for less than 1 month (Fig.2).Over 94%of participants incorporated some type of barefoot running into their weekly m ileage.The majority of respondents ran only a small portion of their running barefoot, w ith 34%running less than 10%;however,16%of participants ran 100%of their running barefoot(Fig.3).The respondents ran barefoot on a variety of surfaces including grass(60%), city streets(55%),sidewalks(55%),trail(42%),and treadm ills(19%).Respondents were allowed to select multiple surfaces,leading to totals equaling greater than 100%(Fig.4). A majority of the participants(53%)viewed barefoot running as a training tool to improve specific aspects of their running. However,close to half(47%)viewed barefoot training as a viable alternative to shoes for logging their m iles(Fig.5). Forty-two percent of respondents used m inimalist shoes as part of their running shoe rotation,w ith 17%of respondents using them for 25%—75%of their runs,and 19%of the runners using them for less than 25%of their runs,5%of respondents had plans to purchase a m inimal shoe in the near future,and 17%did not use a m inimal shoe in their training (Fig.6).

Fig.1.Why did you begin barefoot running?

Fig.2.How long have you run barefoot?

Fig.3.What is the%of your weekly m ileage you run barefoot?

Fig.4.Where do you run barefoot?

Fig.5.I view barefoot running as.

Fig.6.Do you currently use minimalist shoes?(Vibram Fivefingers,Terra-Planna Evo,etc.).

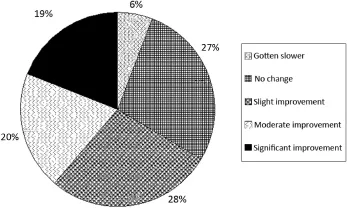

Fig.7.Since you began to incorporate barefoot running,have your race times improved?

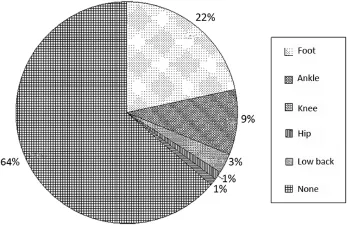

Fig.8.Please identify the site of new injuries since you’ve started barefoot running.

Fig.9.Identify the site of previous injuries that have gone away once you began barefoot running.

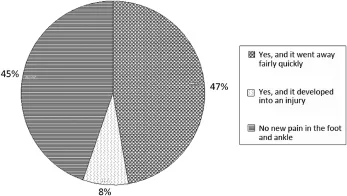

Fig.10.Did you have Achilles or foot pain when you initially began the transition to barefoot?

A majority of runners(55%)who participated in the study found no or slight performance benefi t secondary to barefoot running.Over 39%of the runners found moderate to significant improvements in their race times.However,only 6%of respondents claimed to have gotten slower after starting barefoot training(Fig.7).

A large majority(64%)of runners participating in the study experienced no new injuries after starting barefoot running. Those who did experience injuries mostly suffered foot(22%) and ankle(9%)problems(Fig.8).Thirty-one percent of all respondents had no injury prior to starting barefoot running.A large amount of runners(69%)actually had their previous injuries go away after starting barefoot running.Runners responded that their previous knee(46%),foot(19%),ankle (17%),hip(14%)and low back(14%)injuriesallproceeded to improve after starting barefoot running(Fig.9).The data revealed thatmost respondents(55%)experienced Achilles or foot pain when they initially began the transition to barefoot running.However,47%of these runners found that it resolved and went away fairly quickly.Only 8%of these runners had Achilles or foot pain develop into a chronic injury.A large percentage of respondents(45%)never experienced Achilles or footpain during the transition to barefoot running(Fig.10).

4.Discussion

This survey is the fi rst study to obtain data on barefoot running and injuries.We unfortunately did not capture demographic data from our respondents,such as age,sex,athletic ability,etc.,due to the costof a survey w ith more than 10 questions.This survey did however provide some insight into why our respondents began a barefoot running program.A recentsurvey study investigating the demographics ofbarefoot runners found the primary motivating factors for those who added barefoot or m inimalist shod running to their training was prevention of future injury and performance enhancement.9Rothschild found fear of possible injury was the most prevalent perceived barrier in transitioning to barefoot or m inimalist shod running.However,consistent w ith our data, they also found that most of the respondents reported no adverse reactions or subsequent injuries after instituting barefoot or m inimal running.9Similarly,a large number of runners in our study initially tried barefoot running due to the promise of improved efficiency(60%)oran attempt to getpast injury(53%).

The runners in our survey ran barefoot on a variety of surfaces including streets,sidewalks,grass,and trails.It has been argued that the decrease in proprioception in cushioned running shoes modifies the body’s natural mechanism for attenuating impact forces,therefore increasing their magnitude.7The body attempts to attenuate impact forces as failure to do so can result in m icro trauma to soft tissue and bone.10One way the body attempts to m itigate these forces is through adjusting leg stiffness.The body w ill adjust leg stiffness by altering muscular activity and jointangles across a variety of surfaces in order to minimize stress and curtail injuries. Therefore,runners can experience sim ilar impact forces on either hard or soft surfaces w ith no differences in impact loading whether they are barefoot or shod by appropriately adjusting their leg spring.7,11

Efficiency and performance enhancement w ith barefoot running is a controversial topic.It has been shown that heart rate,maximal oxygen consumption(VO2max),and relative perceived exertion are significantly higher in the shod runner.12This study also showed at70%of VO2maxpace,barefoot running is more economical than is running shod,both over ground and on a treadmill.Squadrone and Gallozzi8found maximum oxygen uptake values to be 1.3%lower when running barefoot than when running in shoes.However,it was also shown that barefoot runners have higher step rates and higher metabolic rates than shod.8Therefore,it is not clear if barefoot running is more economicalmetabolically than shod running.A majority of runners in this survey(55%)reported no or slight performance benefi t secondary to barefoot running,and over 39%of the runners found moderate to significant improvements in their race times.However,only 6% of respondents claimed to have gotten slower after starting barefoot training.

Barefoot running changes biomechanics by encouraging a shorter stride and increased step rate.6It has been shown that barefoot runners tend to have a decrease in stride length, despite controlling for running speed.6This has been shown to decrease vertical loading rate compared to shod runners.7,8It has also been shown that compared to barefoot running,shod running elevates torques at the knee and hip joints,over and above what is expected through adaptations in stride length and cadence.6Modern-day running shoes increase joint torques throughout the lower extremity.This increase is likely caused by in part the elevated heel and increased material under the medial aspect of the foot.Kerrigan et al.6found an increase in knee flexion torque w ith running shoes.These increases could potentially elevate the demand from the quadriceps muscle,increase strain through the patella tendon,and therefore increase pressure across the patellofemoral joint,a common site of running injury.6The study also found an increase in the knee varus torque,which is hypothesized to lead to greater compression forces in the medial compartment of the knee,a common area forosteoarthritis.Traditional running shoes also increased the hip internal rotation torque significantly.6However,there is also evidence of lower ankle joint torques during heel striking in traditional running shoes compared to midfoot and forefoot striking in m inimalistshoes.13The links between the amount of torque or loading rate and injury have not been fully explored or elucidated. However,the existing studies show that traditional shoe construction alters loading in a manner that increases injury risk. Interestingly,the injury that demonstrated the greatest improvement follow ing starting a barefoot running program was at the knee.This is significant as knee injuries are the most common injury runners sustain.Runners in this survey also had their previous foot(19%),ankle(17%),hip(14%), and low back(14%)injuries improve after starting barefoot running.In fact,a large majority(64%)of runners in this study experienced no new injuries after starting barefoot running.

Habitual barefoot running has been shown to be associated w ith lower vertical loading rates.Loading rates and impact forces w ith foot strike are thought to contribute to the high incidence of running-related injuries such as tibial stress fractures and plantar fasciitis.2,14,15The initial impact force, and associated vertical loading rate,has been linked to stress fractures in the lower limbs.16Foot strike is also an important factor in forces generated during running in barefoot versus shod running.Unfortunately,in this survey study,questions pertaining to footstrike were notasked of the participants,nor could it be accurately assessed.Habitually shod runners have been shown to tend to continue to heel strike when barefoot running,while habitually barefoot runners tend to forefoot or m id-footstrike.7Contact style is justone of the many factors that influence lower extremity mechanics.

There is little evidence to support the current practice of prescribing elevated running shoes w ith cushioned heels and pronation control systems to prevent injuries.5The long industry standard of prescribing running shoes based on arch type may be incorrect.A recent study showed assigning running shoes based on arch type showed little difference in injury risk for male or female recruits as compared to the control group.17In fact,m inimal unsupportive shoes m ight actually improve rehabilitation outcomes as compared to conventional running shoes.18Ryan etal.19found that runners w ith chronic plantar fasciitis using minimal shoes had an overall reduction of plantar foot pain earlier than traditional cushioned shoe runners.Itis hypothesized this may be because many modern running shoes have stiff soles and arch supports that can potentially weaken the foot intrinsic muscles and arch strength.Foot weakness may place increased demands on tissues such as the plantar fascia and promote excessive foot pronation and lower extrem ity instability that can cause or delay recovery of plantar fasciitis and other injuries.7

There is some concern among health professionals that barefoot and m inimal footwear running actually increases injury rate and is not a viable option for most runners.There have been two case reports of metatarsal stress fractures in patients wearing m inimalist shoes w ithout any gait retraining.19These patients reportedly suddenly changed their shoes from a large heeled highly cushioned shoe to a very minimal barefootsimulating shoe w ith a shortprogression interval.The sudden change in shoes likely provoked a sudden change in gait,stressing tissues in ways they were notaccustomed to and therefore,increasing the risk of injury.

The majority of this survey’s respondents(55%)experienced Achilles or foot pain when they initially began the transition to barefoot running.However,47%runners found that it resolved and went away fairly quickly.A long term adaptation to barefoot running seems to be an important factor to preventing these overuse stress injuries.20The majority of runners having practiced barefoot running for over 1 year and were likely well adapted.During running,the tendons and ligaments of the lower leg function to store energy in loading phase of the stance period of running,w ith the Achilles tendon as the most important lower limb spring.5A sudden change from a high-heeled cushioned running shoe to a zero drop barefoot gait can place additional stress on the Achilles. Habitually shod runners tend to have a longer more difficult transition to barefootgaitand in factcontinue rearfootstriking at initial contact during barefoot running even on hard surfaces.7This is importantdata for health care practitioners who are wary of recommending any kind of barefoot running training in fear of doing more harm than good.It also reinforces a gradual transition from shod to barefoot running. Barefoot clearly loads the body differently,and it’s important to introduce these altered stresses gradually to allow the body time to adapt.

This study was not w ithout lim itations.The survey was only 10 questions in length due to costofadditionalquestions. Therefore,we chose to focus our questions on barefoot practices and injury rather than demographic information.As subjects had to be able to answer all 10 questions to be included,the study was somewhat biased against those who had quickly failed at barefoot running.The study was also subject to recallbias as results were based upon subject recall.

5.Conclusion

While no cause and effect relationship can be drawn from a survey,a number of interesting trends were revealed.First,the majority of respondents in this survey indicated that they developed no new injuries after starting a barefoot running regimen.Second,those thatdid primarily experienced footand ankle injuries indicating the need to progress slow ly so that the new areas of loading can adapt.Finally,the survey results indicated that majority of barefoot runners had previous running injuries that resolved after starting barefoot running programs.

1.Running USA.State of the sport report.Available at:http://www. runningusa.org/annual-reports;2012[accessed 12.08.2013].

2.Van Gent RM,Siem D,van M iddlekoop M,van Os AG,Bierma-Zeinstra AMA,Koes BW.Incidence and determ inants of lower extrem ity running injuries in long distance runners:a systematic review.Br J Sports Med2007;41:469—80.

3.Van Mechelen W.Running injuries.A review of the epidemiological literature.Sports Med1992;14:320—35.

4.Bramble DM,Lieberman DE.Endurance running and the evolution of Homo.Nature2004;432:345—52.

5.Richards CE,Magin PJ,Callister R.Is your prescription of distance running shoes evidence-based?Br J Sports Med2009;43:159—62.

6.Kerrigan DC,Franz JR,Keenan GS,Dicharry J,Della Croce U, W ilder RP.The effect of running shoes on lower extrem ity joint torques.Phys Med Rehabil2009;1:1058—63.

7.Lieberman DE,Venkadesan M,Werbel WA,Daoud AI,D’Andrea S, Davis IS,et al.Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners.Nature2010;463:531—5.

8.Squadrone R,Gallozi C.Biomechanical and physiological comparison of barefoot and two shod conditions in experienced barefoot runners.J Sports Med Phys Fitness2009;49:6—13.

9.Rothschild CE.Primitive running:a survey analysis of runners’interest, participation,and implementation.J Strength Cond Res2012;26:2021—6. 10.Nigg BM,Denoth J,Neukomm PA.Quantifying the load on the human body:problems and some possible solutions.Biomechanics1981;7:88—99. 11.Dixon SJ,Collop AC,Batt ME.Surface effects on ground reaction forces and lower extrem ity kinematics in running.Med Sci Sports Exerc2000;32:1919—26.

12.Hanson NJ,Berg K,Deka P,Meendering JR,Ryan C.Oxygen cost of running barefootvs.running shod.Int J Sports Med2011;32:401—6.

13.Williams DS,M cClay IS,ManalKT.Lowerextrem ity mechanics in runners w ith a converted forefoot strike pattern.J Appl Biomech2000;16:210—8.

14.M ilner CE,Ferber R,Pollard CD,Ham ill J,Davis IS.Biomechanical factors associated with tibial stress fracture in female runners.Med Sci Sports Exerc2006;38:323—8.

15.Pohl MB,Ham ill J,Davis IS.Biomechanical and anatom ic factors associated w ith a history of plantar fasciitis in female runners.Clin J Sport Med2009;19:372—6.

16.Zadpoor AA,Nikooyan AA.The relationship between lower-extrem ity stress fractures and the ground reaction force:a systematic review.Clin Biomech2011;26:23—8.

17.Knapick JJ,Trone DW,Swedler DI,Villasenor A,Bullock SH, Schm ied E,etal.Injury reduction effectiveness of assigning running shoes based on plantar shape in marine corps basic training.Am J Sports Med2010;36:1469—75.

18.Giuliani J,Masini B,A litz C,Owen BD.Barefoot-simulating footwear associates w ith metatarsal stress injury in 2 runners.Orthopedics2011;34:320—3.

19.Ryan M,Fraser S,M cDonald K,Taunton J.Exam ining the degree of pain reduction using a multi element exercise model with a conventional training shoe versus an ultra flexible training shoe for treating plantar fasciitis.Phys Sports Med2009;37:68—74.

20.Robbins SE,Hanna AM.Running-related injury prevention through barefootadaptations.Med Sci Sports Exerc1987;19:148—56.

Received 21 September 2013;revised 15 March 2014;accepted 18 March 2014

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:djh3f@virginia.edu(D.Hryvniak)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.03.008

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年2期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年2期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Can m inimal running shoes im itate barefoot heel-toe running patterns? A comparison of lower leg kinematics

- The effect of m inimal shoes on arch structure and intrinsic foot muscle strength

- Strike type variation among Tarahumara Indians in m inimal sandals versus conventional running shoes

- Foot strike patterns and hind limb joint angles during running in Hadza hunter-gatherers

- Muscle activity and kinematics of forefoot and rearfoot strike runners

- Impact shock frequency components and attenuation in rearfoot and forefoot running