海洋浮游桡足类摄食纤毛虫的研究*

张武昌 陈 雪, 李海波, 丰美萍, 于 莹, 赵 苑 肖 天

(1.中国科学院海洋研究所海洋生态与环境重点实验室 青岛 266071;2.中国科学院大学 北京 100049)

20世纪70年代,表面荧光显微镜的应用使得人们可以计数海水中的浮游细菌(Hobbieet al,1977;Sieburth,1978),随后人们发现了104—105cell/mL的蓝细菌(Johnsonet al,1979;Waterburyet al,1979)在水体中广泛分布。由于体积微小,不能被桡足类摄食,这些微微级生物的生产力能否被传递到高层营养级直至鱼类是海洋浮游生态学关注的一个问题,寻找他们的摄食者也成为随后研究的热点。

Azam 等(1983)设想细菌等生物被鞭毛虫和纤毛虫利用,提出了微食物环的概念。Sherr等(1988)把微微级自养生物加入到微食物环,一起组成了微食物网。在这些设想的微型浮游生物营养关系中,浮游纤毛虫与异养腰鞭毛虫(dinoflagellates)、异养鞭毛虫(flagellates)同属于海洋生态系统微型浮游动物(microzooplankton),它们以微微级浮游生物为食物,同时也被中型浮游动物(mesozooplankton)摄食。

海洋浮游纤毛虫是一类具纤毛的单细胞原生动物,属于纤毛门(Ciliophora),多数属于旋毛纲(Spirotrichea)下的寡毛亚纲(Oligotrichia)及环毛亚纲(Choreotrichia)。浮游纤毛虫的粒级在 10—200μm之间,根据壳的有无分为具壳的砂壳纤毛虫(900余种)和无壳纤毛虫(约 150种),浮游纤毛虫在自然水体中的丰度约为 1×103ind./L,在大多数情况下,无壳纤毛虫的丰度大于砂壳纤毛虫。在微食物网中,浮游纤毛虫由于粒级比异养鞭毛虫(2—20μm)大,易于被桡足类等中型浮游动物摄食,成为联系海洋浮游微食物网和经典食物链(大型浮游植物-桡足类等中型浮游动物-鱼)的重要中间环节。

在20世纪80年代,纤毛虫被上层营养级生物利用的研究受到广泛关注,如Porter等(1979),Conover(1982),Sherr等(1986),Stoecker等(1990),Gifford(1991),Sanders等(1993)等。桡足类是中型浮游动物(>200μm)的优势类群,大约占浮游动物生物量的80%(Verityet al,1996),其饵料通常包括藻类、浮游纤毛虫等微型浮游生物,其中藻类等浮游植物被认为是其主要饵料来源(Calbetet al,2005)。但是近来的研究表明,浮游植物很难提供桡足类自身生长代谢所需的全部营养物质(Damet al,1994;Carlottiet al,1996;Petersonet al,1996),需要有其它的饵料补充,有实验表明在藻类和纤毛虫共存的情况下桡足类优先摄食纤毛虫(Stoeckeret al,1985,1987)。因此大多数关于纤毛虫被摄食的研究都是桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食。

桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食在实验室(Berket al,1977;Robertson,1983)和自然海区(Giffordet al,1988;Tiselius,1989)的研究均已开展。我国目前还尚未开展实验室内桡足类摄食浮游纤毛虫的研究,在自然海区的相关研究也很少(Huoet al,2008)。本文阐述了海洋浮游桡足类摄食纤毛虫的研究历史和现状,为我国桡足类摄食纤毛虫的研究提供借鉴。

1 浮游桡足类摄食纤毛虫的早期证据

人们在无意中积累了一些纤毛虫被桡足类摄食的证据。间接的证据包括:1.Sheldon等(1986)和Smetacek(1981)分别发现围隔和自然海区中纤毛虫的生物量与桡足类的生物量常出现负相关关系;2.Heinle等(1977)用碎屑产生的纤毛虫(无种类信息)来培养桡足类Eurytemora affinis,产卵率和用浮游植物喂养的效果一样,所以推断桡足类是摄食纤毛虫的。

直接的证据是在一些桡足类的肠道(Mullin,1966;Harding,1974)和粪便(Turneret al,1983;Turner,1984)中发现砂壳纤毛虫的壳。Berk等(1977)用盾纤类海洋纤毛虫尾丝虫Uronema nigricans(直径为 8.88—17.30μm)喂养桡足类E.affinis,饵料丰度为 4.17—7.44×103mL–1,E.affinis的清滤率为 0.068—0.934 mL/(ind.·h),摄食率为 717—5688ind.纤毛虫/(ind.桡足类·h)。

由于无壳纤毛虫很脆弱,容易解体,所以无法确认培养过程中无壳纤毛虫的消失是被摄食所引起的,还是由于其他原因造成无壳纤毛虫解体引起的。直到Merrell等(1998)用 CMFDA(5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate)染料为无壳纤毛虫染色,喂养桡足类E.affinis,并用荧光显微镜观察到桡足类体内有荧光,确认无壳纤毛虫确实被桡足类E.affinis摄食。

2 桡足类摄食纤毛虫的实验室内研究

2.1 桡足类摄食纤毛虫的清滤率和功能反应

实验室内研究是指将捕食者和室内培养的纤毛虫共同培养,大多数研究采用一种捕食者摄食一种纤毛虫,根据培养前后纤毛虫丰度的变化估计纤毛虫被摄食的情况。目前已开展的实验室内用桡足类进行培养的研究较少(表1),采用的桡足类种类有6种,其中研究最多的是Acartia tonsa;采用的纤毛虫共计13种,其中7种砂壳类和6种无壳类,使用最多的是具沟急游虫(Strombidium sulcatum)。这些研究表明桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率为0.1—58.1mL/(ind.·h)。

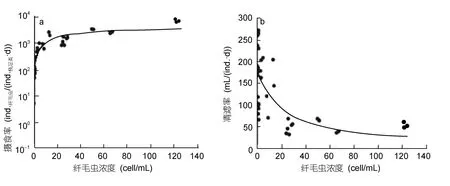

实验室内的研究很少能估计出桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食率随纤毛虫丰度的变化(即功能反应functional response)情况。Frost(1972,1975)根据功能反应曲线提出摄食阈值浓度(threshold concentration),即浮游桡足类的摄食率为零时(停止摄食)的饵料浓度。随饵料浓度升高,摄食率增加,而清滤率保持不变,饵料浓度升高到一定程度后,摄食率不再增加,而清滤率降低(图1),这时的浓度称为摄食饱和浓度(saturation concentration)。为数不多的研究表明桡足类摄食纤毛虫时,饱和浓度很高。例如,桡足类A.tonsa在纤毛虫Tintinnopsis tubulosa的丰度达 2×103ind./L(Robertson,1983)、Favellasp.的丰度达到 3.4×103ind./L(Stoeckeret al,1985)时,其摄食率一直线性增加,说明桡足类的清滤率没有变化。在纤毛虫Eurytemora pectinis浓度达(6—9)×104ind./L时,桡足类A.hudsonica清滤率一直在增加(Turneret al,1983)。Saiz等(1995)得出了A.tonsa摄食S.sulcatum的功能反应曲线,纤毛虫的丰度达到 1×104ind./L后,桡足类的摄食率才不再增加。Kiorboe等(1996)发现S.sulcatum丰度在(0—2.5)×104ind./L的范围内,A.tonsa的清滤率都没有减少的趋势。

同样地,对桡足类摄食纤毛虫的摄食阈值浓度的研究更少。在桡足类A.tonsa摄食纤毛虫S.reticulatum的试验中,当S.reticulatum的丰度大于900ind./L(生物量 1μg C/L)时,桡足类的清滤率保持较高,当低于这个丰度数值,清滤率就开始逐渐降低;S.reticulatum丰度低于100ind./L(生物量约0.1μg C/L)时,桡足类完全停止摄食纤毛虫(Jonssonet al,1990)。

2.2 浮游植物对桡足类摄食纤毛虫的影响

A.tonsa摄食纤毛虫时,水中的藻类会影响其对纤毛虫的清滤率,随着藻类丰度增加,桡足类对藻类的清滤率没有显著增加,但是对纤毛虫的清滤率降低(Stoeckeret al,1985,1987)。Stoecker等(1987)推测藻类浓度过高可能会影响桡足类对纤毛虫的探测。

与浮游植物相比,桡足类倾向于摄食纤毛虫(Stoeckeret al,1985)。Jonsson等(1990)认为纤毛虫的粒级并不能解释这种倾向性,因为大多数纤毛虫都比较大,桡足类能达到 100%过滤截留效率。桡足类对纤毛虫有机械感知(Wiadnyanaet al,1989)和化学感知(Stoeckeret al,1987),可以用来解释这种倾向性。

表1 实验室内桡足类摄食纤毛虫的清滤率Tab.1 Clearance rate of copepods on ciliates in laboratory

图1 浮游桡足类的摄食率(a)和清滤率(b)随纤毛虫浓度变化趋势(Saiz et al,1995)Fig.1 The response of planktonic copepods grazing rate and clearance rate along with ciliates concentration(adapted from Saiz et al,1995)

2.3 桡足类摄食纤毛虫的方式和纤毛虫的应对策略

不同桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食方式不同。A.tonsa采取伏击摄食(ambush feeding)(Jonssonet al,1990;Kiorboeet al,1996;Caparroyet al,1998;Broglioet al,2001)的策略。Jonsson等(1990)首先发现了A.tonsa的伏击摄食模式,在伏击摄食时,桡足类感知和捕获单个纤毛虫,A.tonsa自由下降,纤毛虫在距离A.tonsa大触角0.1—0.7mm的时候就能被A.tonsa感知到,而不用真正触碰到大触角,然后A.tonsa开始伏击摄食,运用第二触角等器官截获纤毛虫。A.tonsa完成摄食动作需时仅0.1s。Caparroy等(1998)发现桡足类Centropages typicus通过游泳来过滤海水中纤毛虫,C.typicus的游泳速度(3.5mm/s)比纤毛虫S.sulcatum的游泳速度(0.2mm/s)大得多,S.sulcatum不能逃离C.typicus的摄食流场。A.tonsa体型较小,摄食流场速度低,所以采取伏击摄食的方式。

有的纤毛虫(Mesodinium rubrum,Strobilidium velox,Halteria grandinella)有弹跳行为,即快速游泳(Jonssonet al,1990;Gilbert,1994)。在自然情况下,S.velox在一分钟内弹跳1.7—3.6次,在游泳时间中占的比例为0.8%,H.grandinella在一分钟内弹跳8次,在游泳时间中占比为1.0%。在与桡足类接触之前,这些纤毛虫能感受到流体力学的变化,引发弹跳行为,逃避摄食(Jakobsen,2001;Wuet al,2010)。逃避引发的弹跳行为和自然状况下弹跳行为的速度和距离没有明显变化(Gilbert,1994)。对于伏击摄食纤毛虫的桡足类A.tonsa,自由下降时的流场信号很弱,不足以引发纤毛虫的弹跳行为(Kiorboeet al,1999)。所以用弹跳行为逃避摄食者也不是对所有捕食者都有效。弹跳行为本身可以帮助纤毛虫逃避摄食者,但是由于弹跳对水流造成很大的扰动,也增加了被摄食者发现的可能性。

由于桡足类和纤毛虫行为模式的不同,不同种类的桡足类和纤毛虫的摄食关系也不同(Gismervik,2006)。例如Tortanus setacaudatus能有效摄食砂壳纤毛虫Favella panamensis,但是却不摄食T.tubulosa。这种差异并不能完全用大颗粒可以被优先摄食来解释。Robertson(1983)认为这是由于T.setacaudatus是伏击摄食者,砂壳纤毛虫T.tubulosa比F.panamensis游泳速度慢,因此T.tubulosa对水流的扰动小,与桡足类的相遇几率也小。

因为纤毛虫是运动的,桡足类与纤毛虫的接触几率(contactment rate)也要大于桡足类与浮游植物的接触几率。在这种情况下,纤毛虫被摄食的情况还与扰动有关(Saizet al,1995;Kiorboeet al,1996;Caparroyet al,1998)。小尺度的扰动对桡足类摄食纤毛虫有影响。在一定的扰动强度下(能量耗散率ε=10–3—10–2cm2/s3),A.tonsa对纤毛虫S.sulcatum的清滤率可以达到平静水体的4倍,但是扰动强度增大(ε=10–1—10cm2/s3)时,清滤率减少,不过仍比平静水体中的清滤率高(Saizet al,1995)。桡足类Centropages typicus在ε=2.9×10–2—3×10–1cm2/s3时,对纤毛虫S.sulcatum的清滤率可以达到平静水体的4倍,但是扰动强度增大(ε=4.4cm2/s3)时,清滤率减少到平静水体中的水平(Caparroyet al,1998)。

砂壳纤毛虫被摄食的方式目前没有定论。Robertson(1983)在培养中没有发现破损的壳,加上在桡足类粪便中发现完整的壳,所以认为桡足类吞食整个的砂壳纤毛虫。Turner等(1983)在加入桡足类的培养瓶(实验瓶)中发现空壳的比例高于对照瓶(没有加桡足类),而且对照瓶中的空壳没有变形,而实验瓶中的空壳很多都被弄皱变形,所以认为不能排除有些砂壳纤毛虫的肉体被摄食,而壳没有被摄食的可能性,也有可能当桡足类触碰到砂壳纤毛虫时,砂壳纤毛虫肉体从壳中逃出。

3 海上原位培养研究桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率

3.1 原位培养研究桡足类摄食纤毛虫的方法

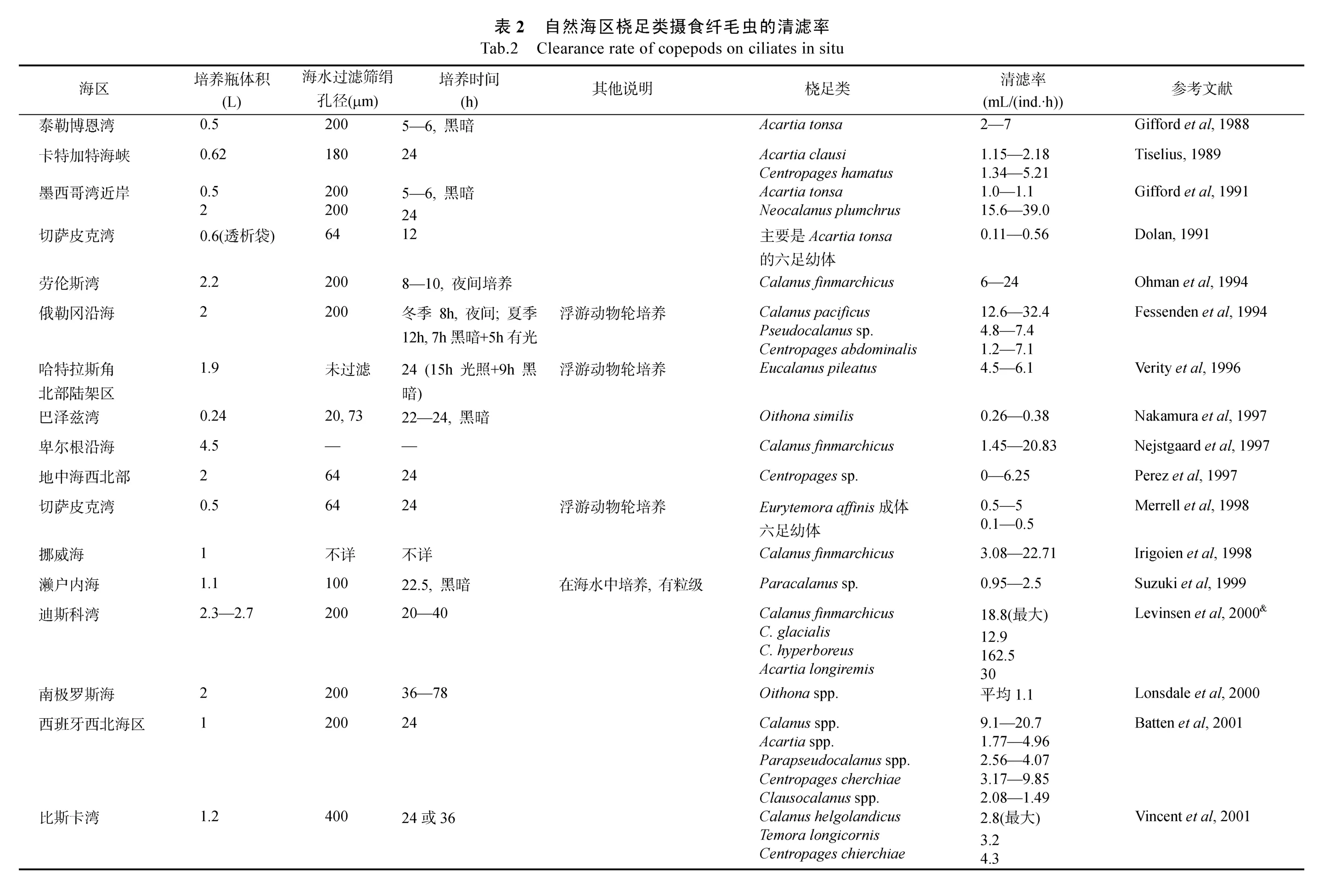

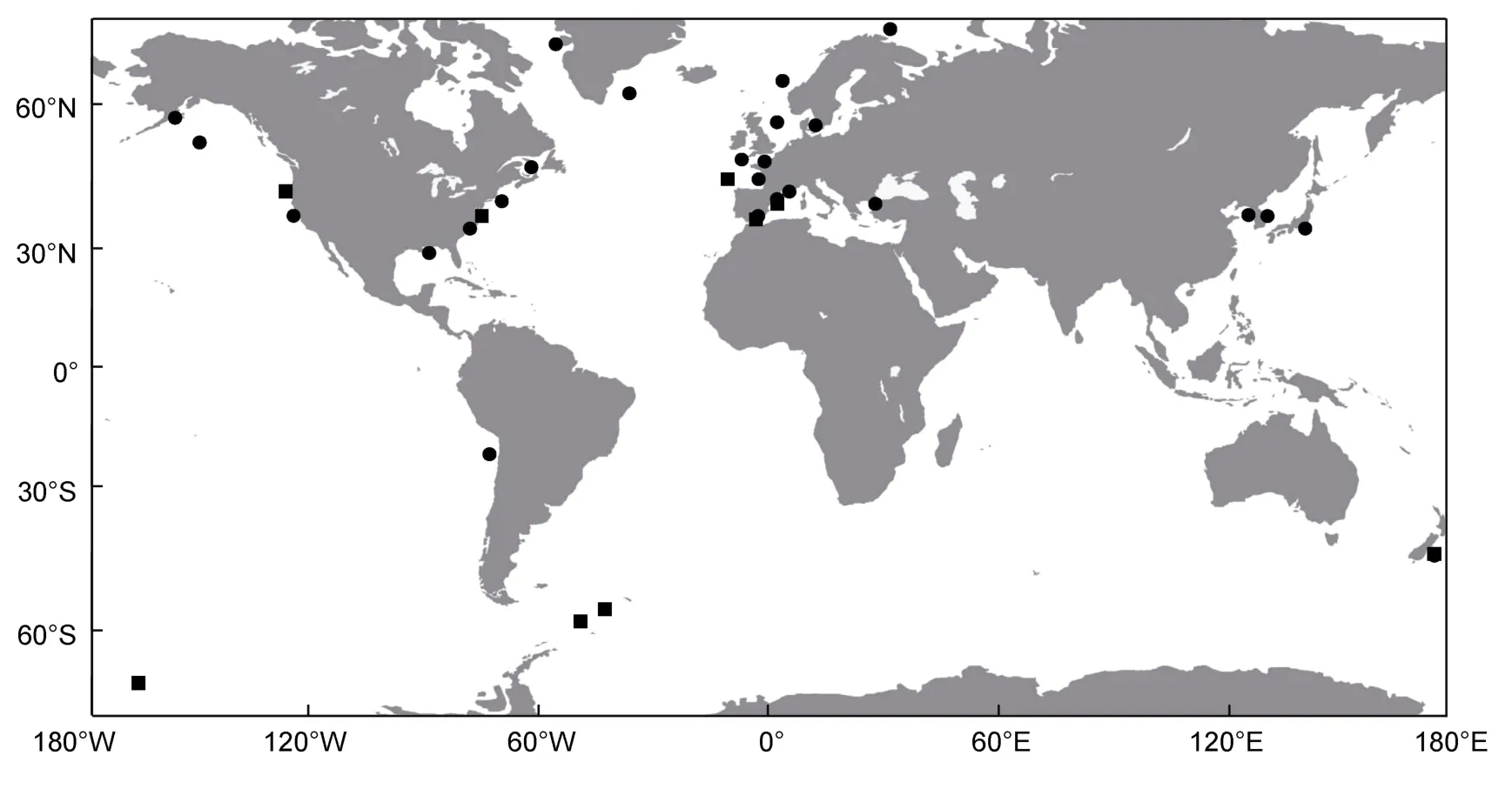

海上原位培养研究纤毛虫被摄食的情况是指自然海区的纤毛虫群落被摄食的情况。研究桡足类摄食的方法大多是进行桡足类培养实验,将自然海水加入培养瓶中,没有添加桡足类的培养瓶作为对照瓶,添加桡足类的培养瓶为实验瓶。将培养瓶放在模拟自然环境(主要是温度、扰动和光照)中培养一段时间,和对照瓶纤毛虫丰度相比较,实验瓶的减少量即被视为桡足类的摄食量。研究桡足类群体在自然状况下对饵料中纤毛虫的摄食开始于 Gifford等(1988),其后有约30个相似的研究开展起来(表2)。这些研究的海区主要是离岸很近的港湾或海边实验室,在开阔水域的研究资料很少(表2,图2)。

大多数培养的培养体积都没有超过 3L,一般在2L左右,个体小的桡足类使用的培养瓶小些。培养时间大多为24h,最长为78h。大多数培养中,用来培养的海水用过滤的方法排除其他摄食者,用来过滤的筛绢孔径最小为 20μm,最大为 400μm。有的培养中为了消除桡足类代谢营养盐造成的影响,在培养瓶中加富了营养盐(表2)。温度的模拟主要有恒温室和流水控温培养,扰动的模拟为浮游动物轮。光照方面要考虑的问题主要是模拟自然的光照周期和避免强光照射。

图2 自然海区现场的浮游纤毛虫被桡足类摄食的研究地点分布图Fig.2 Locations of in situ incubation stations for planktonic ciliates ingested by copepods

Roman等(1980)研究了用培养瓶进行现场桡足类摄食实验的牢笼效应(containment effect)或称瓶子效应(bottle effect),那时的桡足类摄食实验主要是研究对浮游植物的摄食,因此Roman等(1980)的结果显示培养过程中桡足类会释放营养盐,从而导致培养瓶中浮游植物生长快一些,导致低估对浮游植物的摄食。在桡足类摄食纤毛虫的培养实验中,牢笼效应也可能导致培养瓶中纤毛虫的生长也快一些,但是没有研究对此进行评估,所有的研究中都没有考虑牢笼效应。

现场培养的方法也存在一些问题。这个方法的前提是假设纤毛虫的减少是由桡足类造成的,但是这个假设是有问题的,一些其他因素也可能导致纤毛虫的减少,如遇到气泡或过度扰动(Gifford,1985,1993)。Gifford等(2007)的培养中,海水没有过滤的主要目的就是尽量减少对纤毛虫的伤害。培养过程中无壳纤毛虫的死亡也是个问题,例如没有添加桡足类的对照瓶中无壳纤毛虫的死亡率达80%(Tiselius,1989)。

大多数海上添加桡足类培养是对几个种进行培养,对桡足类群体进行的研究较少。在海上培养的桡足类种类(表2)有:Acartia属(A.bifilosa,A.clause,A.hongi,A.longiremis,A.tonsa),Calanus属(C.finmarchicus,C.helgolandicus,C.pacificus,C.sinicus,C.glacialis,C.hyperboreus),Centropages属(C.abdominalis,C.cherchiae,C.hamatus,C.typicus),Eucalanus属(E.bungii,E.pileatus),Neocalanus属(N.cristatus,N.plumchrus,N.flemingeri),Oithona属(O.davisae,O.similis)和Temora属(T.longicornis)。桡足类六足幼体的摄食也得到研究(Stoeckeret al,1987;Dolan,1991;Fessendenet al,1994;Merrellet al,1998)。

3.2 原位培养研究桡足类摄食纤毛虫的结果

桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率最大为C.hyperboreus的 162.5mL/(ind.·h),其次为C.helgolandicus的 98 mL/(ind.·h)和N.cristatus的 70.8mL/(ind.·h),其他大多数清滤率低于 40mL/(ind.·h)(表2)。桡足类体长(或体重)增加,清滤率增加,但是单位体重的清滤率却随体长增加而减小,即个体小的桡足类摄食比较活跃(Levinsenet al,2000)。

有的培养实验把纤毛虫分成不同的粒级,例如Levinsen等(2000)、Liu等(2005a)和 Fileman等(2007)把纤毛虫分为 20μm 以上和 20μm 以下两个体长组,Vincent(2001)分为40μm以上和以下,Koski等(2002)分为30μm以上和以下。这些培养结果表明,桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率随纤毛虫尺寸的增加而增加(Tiselius,1989;Nejstgaardet al,1997)。

目前几乎所有的实验结果(Giffordet al,1988;Atkinson,1996;Castellaniet al,2005)都表明,桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率大于对浮游植物的清滤率,说明桡足类倾向于选择摄食纤毛虫。这种选择性摄食的原因可能是纤毛虫的粒级比较大,悬浮摄食的桡足类对大颗粒的清滤率较大,也可能是伏击摄食的桡足类的行为具有选择性。与摄食藻类相比,桡足类摄食纤毛虫有很多好处,纤毛虫的粒级较大,大多数的桡足类等浮游动物倾向于摄食粒级较大的颗粒。纤毛虫C:N比例比藻类低,蛋白质含量较高(Kiorboeet al,1985;Stoeckeret al,1990),纤毛虫还可以合成桡足类不能合成的不饱和脂肪酸(Sanderset al,1993;Breteleret al,1999,2004),从而有利于桡足类的生长。

Calbet等(2005)对已有的桡足类摄食纤毛虫资料进行了总结,估计了纤毛虫在桡足类饵料中的比例,当浮游植物的生物量为<50μg C/L、50—500μg C/L、>500μg C/L时,纤毛虫在桡足类饵料中的平均贡献分别为 49%、25%、22%,即随着浮游植物生物量的增加,纤毛虫在桡足类饵料中的贡献减少。

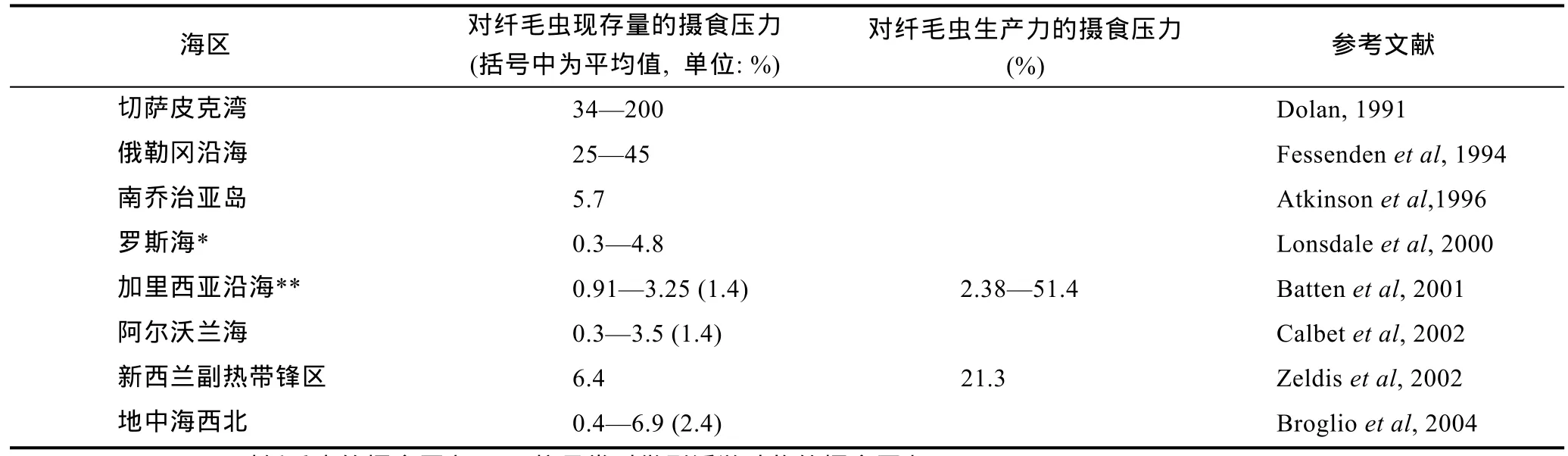

4 自然海区桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食压力

根据自然海区桡足类的丰度和桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率可以估计桡足类群体对纤毛虫的摄食压力。根据现场测定的清滤率和桡足类丰度进行估计的研究不多(Dolan,1991;Fessendenet al,1994;Atkinson,1996;Atkinsonet al,1996;Lonsdaleet al,2000;Batten,2001;Calbetet al,2002;Zeldis,2002;Broglioet al,2004),分布的海区也主要是海湾和离岸很近的海区(图2),除 Dolan(1991)和 Fessenden 等(1994)报导桡足类群体摄食纤毛虫生物量的摄食压力为 45%—200%外,其他研究结果均比较一致:桡足类群体对纤毛虫生物量的摄食压力大约为每天5%(表3)。Dolan(1991)研究发现,在切萨皮克湾的表层桡足类(主要是幼体)的丰度高达80ind./L,这是近岸富营养水体中的情况,因此桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食压力较高。

表3 不同海区现场培养得出的纤毛虫每天被中型浮游动物(主要是桡足类)摄食的压力Tab.3 Grazing pressure of mesozooplankton(mainly copepods)on ciliates by in situ incubation

此外,Fileman等(2007)的研究结果表明,英国Celtic海的桡足类群体对原生动物 PZP(protozooplankton,主要为纤毛虫和异养甲藻)的摄食压力与水华暴发有关,水华期和非水华期的摄食压力分别为 2%—10%和12%—17%。Fileman等(2010)研究发现,英吉利海峡桡足类Calanus helgolandicus和Acartia clausi的种群对 PZP的摄食压力在 2002年为 3%—32%(平均17%),2003年为 0.1%—15%(平均 3%),其研究结果表明桡足类对PZP的摄食压力与调查年份也有关。

根据桡足类的摄食能力在一定程度上可以估计摄食压力与桡足类丰度的关系。Stoecker等(1985)计算Acartiaspp.的丰度为3—4ind./L时,就可以控制砂壳纤毛虫Favellasp.的生长。Calbet等(2005)总结了桡足类摄食纤毛虫的摄食率为 0.016—0.029μg C纤毛虫/(μg C桡足类·d),要每天摄食纤毛虫生物量的 5%,需要桡足类(每只体重为10μg C)的丰度为0.7ind./L。

Nielsen等(1994)使用文献中的清滤率和桡足类的丰度估计桡足类对>50μm ESD(equivalent spherical diameter,等效球体直径)纤毛虫的摄食压力与纤毛虫的生长率相抵,但是小个体纤毛虫的生长率要大于桡足类群体对其摄食压力。

5 结语

自20世纪80年代以来,人们开始在实验室内和海上现场研究浮游桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食。实验室内有限的研究发现:桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食存在功能反应;相比于浮游植物,桡足类倾向于摄食纤毛虫;不同桡足类对纤毛虫有不同的摄食方式,有的纤毛虫有逃避桡足类摄食的行为。自然海区桡足类对纤毛虫的摄食研究主要在近岸海区,所用的方法较一致,多是在自然海区采集纤毛虫群体的样品,添加几个种类的桡足类,模拟现场环境进行对照培养实验。目前的研究方法还存在一些问题,例如没有考虑牢笼效应、气泡或过度扰动对纤毛虫的影响以及培养过程中纤毛虫的自然死亡等,这些都是在今后的研究中亟待解决的。原位培养研究桡足类摄食纤毛虫,得出了桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率与桡足类和纤毛虫的粒级有关;桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率大于对浮游植物的清滤率,这个结果与室内研究一致。根据自然海区桡足类的丰度和桡足类对纤毛虫的清滤率可以估计桡足类群体对纤毛虫的摄食压力,得出的结果较一致,大约为每天 5%。目前已经开展研究的海区多是近岸海区,对大洋的研究较少,需要加强对大洋中桡足类摄食纤毛虫的研究。

Atkinson A,1996.Subantarctic copepods in an oceanic,low chlorophyll environment:ciliate predation,food selectivity and impact on prey populations.Marine Ecology Progress Series,130(8):85—96

Atkinson A,Shreeve R S,Pakhomov E Aet al,1996.Zooplankton response to a phytoplankton bloom near South Georgia,Antarctica.Marine Ecology Progress Series,144(1):195—210

Ayukai T,1987.Predation byAcartia clausi(Copepoda:Calanoida)on two species of tintinnids.Marine Microbial Food Webs,2(1):45—52

Azam F,Fenchel T,Field J Get al,1983.The ecological role of water-column microbes in the sea.Marine Ecology Progress Series,10(3):257—263

Batten S D,Fileman E S,Halvorsen E,2001.The contribution of microzooplankton to the diet of mesozooplankton in an upwelling filament off the northwest coast of Spain.Progress in Oceanography,51(2):385—398

Berk S G,Brownlee D C,Heinle D Ret al,1977.Ciliates as food sources for marine planktonic copepods.Microbial Ecology,4(1):27—40

Bollens G C R,Penry D L,2003.Feeding dynamics ofAcartiaspp.copepods in a large,temperate estuary(San Francisco Bay,CA).Marine Ecology Progress Series,257:139—158

Breteler W C M K,Koski M,Rampen S,2004.Role of essential lipids in copepod nutrition:no evidence for trophic upgrading of food quality by a marine ciliate.Marine Ecology Progress Series,274:199—208

Breteler W C M K,Schogt N,Baars Met al,1999.Trophic upgrading of food quality by protozoans enhancing copepod growth:role of essential lipids.Marine Biology,135(1):191–198

Broglio E,Johansson M,Jonsson P R,2001.Trophic interaction between copepods and ciliates:Effects of prey swimming behavior on predation risk.Marine Ecology Progress Series,220:179—186

Broglio E,Jonasdottir S H,Calbet Aet al,2003.Effect of heterotrophic versus autotrophic food on feeding and reproduction of the calanoid copepodAcartia tonsa:relationship with prey fatty acid composition.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,31(3):267—278

Broglio E,Saiz E,Calbet Aet al,2004.Trophic impact and prey selection by crustacean zooplankton on the microbial communities of an oligotrophic coastal area(NW Mediterranean Sea).Aquatic Microbial Ecology,35(1):65—78

Calbet A,Broglio E,Saiz Eet al,2002.Low grazing impact of mesozooplankton on the microbial communities of the Alboran Sea:a possible case of inhibitory effects by the toxic dinoflagellateGymnodinium catenatum.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,26(3):235—246

Calbet A,Saiz E,2005.The ciliate-copepod link in marine ecosystems.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,38(2):157—167

Caparroy P,Perez M T,Carlotti F,1998.Feeding behaviour ofCentropages typicusin calm and turbulent conditions.Marine Ecology Progress Series,168:109—118

Carlotti F,Radach G,1996.Seasonal dynamics of phytoplankton andCalanus finmarchicusin the North Sea as revealed by a coupled one-dimensional model.Limnology and Oceanography,41(3):522—539

Castellani C,Irigoien X,Harris R Pet al,2005.Feeding and egg production ofOithona similisin the North Atlantic.Marine Ecology Progress Series 288:173—182

Conover R J,1982.Interrelations between microzooplankton and other plankton organisms.Annales de l'Institut Oceanographique,Paris.Nouvelle Serie,59:31—46

Dam H G,Peterson W T,Bellantoni D C,1994.Seasonal feeding and fecundity of the calanoid copepodAcartia tonsain Long Island:Is onmivory important to egg production?Hydrobiologia,292/293(1):191—199

Dolan J R,1991.Microphagous ciliates in mesohaline Chesapeake Bay waters:estimates of growth rates and consumption by copepods.Marine Biology,111(2):303—309

Dutz J,Koski M,Jonasdottir S H,2008.Importance and nutritional value of large ciliates for the reproduction ofAcartia clauseduring the post spring-bloom period in the North Sea.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,50(3):261—277

Fessenden L,Cowles T J,1994.Copepod predation on phagotrophic ciliates in Oregon coastal waters.Marine Ecology Progress Series,107:103—111

Fileman E,Petropavlovsky A,Harris R,2010.Grazing by the copepodsCalanus helgolandicusandAcartia clauseon the protozooplankton community at station L4 in the western English Channel.Journal of Plankton Research,32(5):709—724

Fileman E,Smith T,Harris R,2007.Grazing byCalanus helgolandicusandPara-Pseudocalanusspp.on phytoplankton and protozooplankton during the spring bloom in the Celtic Sea.Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,348(2):70—84

Frost B W,1972.Effects of size and concentration of food particles on feeding behavior of marine planktonic copepodCalanus pacificus.Limnology and Oceanography,17(6):805—815

Frost B W,1975.A threshold feeding behavior inCalanus pacificus.Limnology and Oceanography,20(2):263—266

Gilbert J J,1994.Jumping behaviour in the oligotrich ciliatesStrobilidium veloxandHalteria grandinella,and its significance as defence against rotifer predators.Microbial Ecology,27(2):189—200

Gifford D J,1985.Laboratory culture of marine planktonic oligotrichs(ciliophora,oligotrichida).Marine Ecology Progress Series,23:257—267

Gifford D J,1991.The protozoan-metazoan trophic link in pelagic ecosystems.Journal of Protozoology,38(1):81—86

Gifford D J,1993.Consumption of protozoa by copepods feeding on natural microplankton assemblages.In:Kemp P F,Sherr B F,Sherr E Bet aleds.Handbook of Methods in Aquatic Microbial Ecology.Lewis Publishers,London:723—729

Gifford D J,Dagg M J,1988.Feeding of the estuarine copepodAcartia tonsaDana- carnivory vs herbivory in natural microplankton assemblages.Bulletin of Marine Science,43(3):458—468

Gifford D J,Dagg M J,1991.The microzooplanktonmesozooplankton link:Consumption of planktonic protozoa by calanoid copepodsAcartia tonsaDana andNeocalanus plumchrusMurukawa.Marine Microbial Food Webs,5(1):161—177

Gifford S M,Rollwagen-Bollens G,Bollens S M,2007.Mesozooplankton omnivory in the upper San Francisco Estuary.Marine Ecology Progress Series,348:33—46

Gismervik I,2006.Top-down impact by copepods on ciliate numbers and persistence depends on copepod and ciliate species composition.Journal of Plankton Research,28(5):499—507

Gismervik I,Andersen T,1998.Prey switching byAcartia clause:experimental evidence and implications of intraguild predation assessed by a model.Marine Ecology Progress Series,45(3):247—259

Harding G C H,1974.The food of deep-sea copepods.Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom,54:141—155

Heinle D R,Harris R P,Ustach J Fet al,1977.Detritus as food for estuarine copepods.Marine Biology,40(1):341—353

Hobbie J E,Daley R J,Jasper S,1977.Use of nuclepore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy.Applied and Environmental Microbiology,33(5):1225—122

Huo Y Z,Wang S W,Sun Set al,2008.Feeding and egg production of the planktonic copepodCalanus sinicusin spring and autumn in the Yellow Sea,China.Journal of Plankton Research,30(6):723—734

Irigoien X,Head R,Klenke Uet al,1998.A high frequency time series at weathership M,Norwegian Sea,during the 1997 spring bloom:feeding of adult femaleCalanus finmarchicus.Marine Ecology Progress Series,172:127—137

Jakobsen H H,2001.Escape response of planktonic protists to fluid mechanical signals.Marine Ecology Progress Series,214:67—78

Johnson P W,Sieburth J M,1979.Chroococcoid cyanobacteria in the sea:a ubiquitous and diverse phototrophic biomass.Limnology and Oceanography,24:928—935

Jonsson P R,Tiselius P,1990.Feeding behaviour,prey detection and capture efficiency of the copepodAcartia tonsafeeding on planktonic ciliates.Marine Ecology Progress Series,60(1):35—44

Kiorboe T,Mohlenberg F,Hamberger K,1985.Bioenergetics of the planktonic copepodAcartia tonsa:relation between feeding,egg production and respiration,and composition of specific dynamic action.Marine Ecology Progress Series,26(1—2):85—97

Kiorboe T,Saiz E,Viitasalo M,1996.Prey switching behaviour in the planktonic copepodAcartia tonsa.Marine Ecology Progress Series,143(1—3):65—75

Kiorboe T,Visser A W,1999.Predation and prey perception in copepods due to hydromechanical signals.Marine Ecology Progress Series,179:81—95

Kobari T,Shinida A,Tsuda A,2003.Functional roles of interzonal migrating mesozooplankton in the western subarctic Pacific.Progress in Oceanography,57(3):279—298

Koski M,Schmidt K,Engstrom-Ost Jet al,2002.Calanoid copepods feed and produce eggs in the presence of toxic cyanobacteriaNodularia spumigena.Limnology and Oceanography,47(3):878—885

Levinsen H,Turner J T,Nielsen T Get al,2000.On the trophic coupling between protists and copepods in arctic marine ecosystems.Marine Ecology Progress Series,204:65—77

Liu H,Dagg M J,Strom S,2005a.Grazing by the calanoid copepodNeocalanus cristatuson the microbial food web in the coastal Gulf of Alaska.Journal of Plankton Research,27(7):647—662

Liu H,Dagg M J,Wu C Jet al,2005b.Mesozooplankton consumption of microplankton in the Mississippi River plume,with special emphasis on planktonic ciliates.Marine Ecology Progress Series,286:133—144

Lonsdale D,Caron D A,Dennett M Ret al,2000.Predation byOithonaspp.on protozooplankton in the Ross Sea,Antarctic.Deep-Sea Research II,47(15):3273—3283

Merrell J R,Stoecker D K,1998.Differential grazing on protozoa microzooplankton by developmental stages of the calanoid copepodEurytemora affinisPoppe.Journal of Plankton Research,20(2):289—304

Mullin M M,1966.Selective feeding by calanoid copepods from the Indian Ocean.In:Barnes H ed.Some Contemporary Studies in Marine Science.George Allen and Unwin Ltd.,London,England:545—554

Nakamura Y,Turner J T,1997.Predation and respiration by the small cyclopoid copepodOithona similis:how important is feeding on ciliates and heterotrophic flagellates.Journal of Plankton Research,19(9):1275—1288

Nejstgaard J C,Gismervik I,Solberg P T,1997.Feeding and reproduction byCalanus finmarchicus,and microzooplankton grazing during mesocosm blooms of diatoms and the coccolithophoreEmiliania huxleyi.Marine Ecology Progress Series,147:197—217

Nielsen T G,Kiorboe T,1994.Regulation of zooplankton biomass and production in a temperate,coastal ecosystems:2.ciliates.Limnology and Oceanography,39(3):508—519

Ohman M D,Runge J A,1994.Sustained fecundity when phytoplankton resources are in short supply:omnivory byCalanus finmarchicusin the gulf of St.Lawrence.Limnology and Oceanography,39(1):21—36

Perez M T,Dolan J R,Fukai E,1997.Planktonic oligotrich ciliates in the NW Mediterranean:growth rates and consumption by copepods.Marine Ecology Progress Series,155(89):89—101

Peterson W T,Dam H G,1996.Pigment ingestion and egg production rates of the calanoid copepodTemora longicornis:implications for gut pigment loss and omnivorous feeding.Journal of Plankton Research,18(5):855—861

Porter K G,Pace M L,Nauwerk A,1979.Ciliate protozoans as links in freshwater planktonic food chains.Nature,279:563—565

Robertson J R,1983.Predation by estuarine zooplankton on tintinnid ciliates.Estuarine,Coastal and Shelf Science,16(1):27—36

Roman M R,Rublee P A,1980.Containment effects in copepod grazing experiments:a plea to end the black box approach.Limnology and Oceanography,25(6):982—990

Saiz E,Kiorboe T,1995.Predatory and suspension-feeding of the copepodAcartia tonsain turbulent environments.Marine Ecology Progress Series,122(1—3):147—158

Sanders R W,Wickham S A,1993.Planktonic protozoa and metazoan:predation,food quality and population control.Marine Microbial Food Webs,7(2):197—223

Sheldon R W,Nival P,Rassoulzadegan F,1986.An experimental investigation of a flagellate-ciliate-copepod food chain with some observations relevant to the linear biomass hypothesis.Limnology and Oceanography,31(1):184—188

Sherr E B,Sherr B F,1988.Role of microbes in pelagic food webs:a revised concept.Limnology and Oceanography,33(5):1225—1227

Sherr E B,Sherr B F,Paffenhofer G,1986.Phagotrophic protozoa as food for metazoans:a “missing link” in marine pelagic food webs? Marine Microbial Food Webs,1(2):61—80

Sieburth J M,1978.Bacterioplankton:nature,biomass,activity,and relationships to the protist plankton.Journal of Phycology,14:31

Smetacek V,1981.The annual cycle of the protozooplankton in the Kiel Bight.Marine Biology,63(1):1—11

Stoecker D K,Capuzzo J M,1990.Predation on protozoa:its importance to zooplankton.Journal of Plankton Research,12(5):891—908

Stoecker D K,Egloff D A,1987.Predation byAcartia tonsaDana on planktonic ciliates and rotifers.Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,110(1):53—68

Stoecker D K,Sanders N K,1985.Differential grazing byAcartia tonsaon a dinoflagellate and a tintinnid.Journal of Plankton Research,7(1):85—100

Suzuki K,Nakamura Y,Hiromi J,1999.Feeding by the small calanoid copepodParacalanussp.on heterotrophic dinoflagellates and ciliates.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,17:99—103

Tiselius P,1989.Contribution of aloricate ciliates to the diet ofAcartia clausiandCentropages hamatusin coastal waters.Marine Ecology Progress Series,56:49—56

Turner J T,1984.Zooplankton feeding ecology:contents of fecal pellets of the copepodsAcartia tonsaandLabidocera aestivafrom continental shelf waters near the mouth of the Mississippi River.Marine Ecology,5(3):265—282

Turner J T,Anderson D M,1983.Zooplankton grazing during dinoflagellate blooms in a Cape Code embayment,with observations of predation upon tintinnids by copepods.Marine Ecology,4(4):359—374

Vargas C A,Gonzalez H E,2004.Plankton community structure and carbon cycling in a coastal upwelling system.I.Bacteria,microprotozoans and phytoplankton in the diet of copepods and appendicularians.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,34(2):151—164

Verity P G,Paffenhofer G A,1996.On assessment of prey ingestion by copepods.Journal of Plankton Research,18(10):1767—1779

Vincent D,Hartmann H J,2001.Contribution of ciliated microprotozoans and dinoflagellates to the diet of three copepod species in the Bay of Biscay.Hydrobiologia,443(1—3):193—204

Waterbury J B,Watson S W,Guillard R Ret al,1979.Widespread occurrence of a unicellular marine planktonic cyanobacterium.Nature,277:293—294

Wiadnyana N N,Rassoulzadegan F,1989.Selective feeding ofAcartia clausiandCentrogages typicuson microzooplankton.Marine Ecology Progress Series,53(1):37—45

Wu C,Dahms H,Buskey E Jet al,2010.Behavioral interactions of the copepodTemora turbinatewith potential ciliate prey.Zoological Studies,49(2):157—168

Yang E,Kang H,Yoo Set al,2009.Contribution of auto- and heterogrophic protozoa to the diet of copepods in the Ulleung Basin,East Sea/Japan Sea.Journal of Plankton research,31(6):647—659

Yang E,Ju S,Choi J,2010.Feeding activity of the copepodAcartia hongion phytoplankton and micro-zooplankton in Gyeonggi Bay,Yellow Sea.Estuarine,Coastal and Shelf Science,88(2):292—301

Zeldis J,James M R,Grieve Jet al,2002.Omnivory by copepods in the New Zealand subtropical frontal zone.Journal of Plankton Research,24(1):9—23

Zervoudaki S,Christou E D,Assimakopoulou Get al,2011.Copepod communities,production and grazing in the Turkish Straits System and the adjacent northern Aegean Sea during spring.Journal of Marine System,86(3):45—56