舱室内爆炸伤复合失血致休克大鼠液体复苏的研究

崔红,王丽丽,周敏,赖西南,肖南

·军事医学·

舱室内爆炸伤复合失血致休克大鼠液体复苏的研究

崔红,王丽丽,周敏,赖西南,肖南

目的比较高渗盐溶液与生理盐水用于舱室内爆炸伤复合失血致休克大鼠液体复苏的治疗效果。方法健康成年雄性SD大鼠147只,固定于模拟舱室内,点爆源距大鼠胸腹部中心11~12cm瞬时引爆,迅速抽离舱内烟雾。炸后将大鼠静置于实验台上测量炸后10min平均动脉压(MAP)并以此为零时相点,由股动脉导管匀速放血造成中度休克。将108只大鼠随机分为无复苏组(对照组)、生理盐水组(NS组)及高渗盐溶液组(HSD组),每组36只。对照组致伤后不予治疗;NS组于伤后90min由股静脉匀速输入失血量3倍的NS,30min输注完毕;HSD组以4ml/kg匀速输入7.5%高渗氯化钠/6%右旋醣酐高渗盐溶液,5min输注完毕。各组分别于150、210、270min时点在存活大鼠中随机处死8只大鼠,测量血气指标,并收集肺、脑组织标本检测含水量。另39只大鼠同上分组,每组13只,致伤复苏方法同前,记录30、90、150、210、270min时点各组血压变化及死亡状况。结果对照组13只大鼠有6只死亡,NS组有3只死亡,HSD组大鼠全部存活至270min时点,组间存活率比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。伤后150min时点,NS组及HSD组大鼠MAP显著增高,210、270min时点NS组MAP逐渐降低,而HSD组降低不明显,270min时点各组间比较差异显著(P<0.05)。在150、210、270min时点,HSD组大鼠肺、脑含水量逐渐下降,而NS组则有上升趋势,组间比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05或P<0.01)。与对照组比较,HSD与NS对血气指标均有一定的改善作用,且在210min及270min时间点,HSD组pH值、PO2高于NS组,乳酸水平低于NS组(P<0.05或P<0.01)。结论HSD可维持爆炸伤复合失血致休克大鼠血流动力学稳定,且在改善血气指标及肺、脑水肿方面的作用优于NS。

舱室爆炸伤;休克,出血性;盐水,高渗;液体复苏

战争环境及日常生活中,密闭舱室爆炸伤发生率均逐年增高。休克是战创伤死亡的重要原因之一,文献报道,战时有32.6%~59.5%的伤员死于创伤失血性休克[1]。若得不到早期救治,休克的死亡率可高达31%。目前关于何种液体更适用于休克的早期复苏尚无定论,美国陆军医学研究和物资司令部(MRMC)及海军研究办公室(ONR)均推荐高渗盐液、人工胶体液或二者的混合液作为容量复苏的首选液体[2],但有临床研究表明,高渗盐溶液与传统等渗晶体液复苏对低血容量休克患者存活率的影响无显著差异[3]。既往对高渗盐溶液的研究多集中在单纯低血容量性休克或颅脑伤合并低血容量休克的液体复苏方面,在舱室密闭环境中多系统受累的爆炸冲击伤基础上发生的创伤失血性休克有其自身特点[4-7],是否可采用高渗盐溶液进行复苏尚未见报道。本研究以高渗盐溶液及生理盐水作为早期容量复苏液体,比较二者对舱室内爆炸伤复合失血致休克大鼠的复苏效果,以期为舱室爆炸伤合并失血致休克患者的早期救治提供理论依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1实验仪器及设备 按照陆军装甲车辆舱室等比例缩小,模拟装甲舱室;MFB-50型发爆器,柱状纸质点爆源(成分包括黑素金0.35g,二硝基重氮酚300mg),NOVA 9型血气分析仪(美国),Sartorius BA61型电子天平(瑞士)。

1.2实验动物 清洁级雄性SD大鼠147只,体重200~220g,由第三军医大学大坪医院野战外科研究所实验动物中心提供。实验前12h禁食,自由饮水。

1.3方法

1.3.1动物模型制备 戊巴比妥钠36mg/kg腹腔注射麻醉大鼠,固定于实验平台上,行左侧股动脉插管,测量并记录爆炸前平均动脉压(MAP);将大鼠固定于模拟舱室内,点爆源距大鼠胸腹部中心11~12cm瞬时引爆,迅速抽离舱内烟雾;炸后将大鼠静置于实验台,测量炸后10min的MAP并以此为零时相点,由股动脉导管匀速放血(30min放总血量的30%)致中度休克。

1.3.2实验方法 108只大鼠按随机数字表法分为无复苏组(对照组)、高渗盐溶液(7.5%高渗氯化钠/6%右旋醣酐)组(HSD组)、生理盐水组(NS组),每组36只。对照组不予任何治疗;NS组于伤后90min由股静脉匀速输入生理盐水,输入量为失血量的3倍,30min输注完毕;HSD组按照4ml/kg液体量匀速输入7.5%高渗氯化钠/6%右旋醣酐高渗盐溶液,5min输入完毕。各组于150、210、270min时间点在存活大鼠中随机处死8只,处死前由股动脉抽取0.3ml血液抗凝用于血气分析,处死后立即收集肺、脑组织标本用于含水量检测。另39只大鼠分组同上,每组13只,观察记录30、90、150、210、270min时间点各组血压变化及死亡状况。实验过程中大鼠体温始终维持在37.0±0.5℃水平。

1.4统计学处理 采用SPSS 13.0软件进行统计分析,数据结果以±s表示,多组间比较采用重复测量的方差分析,进一步两两比较采用t检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1各组死亡率比较 对照组13只大鼠有6只死亡,死亡率46.2%,其中3只大鼠死亡发生在爆炸伤后210min时。NS组在210min时有1只、270min时有2只动物死亡占23.1%。HSD组大鼠至270min时全部存活,死亡率为0%。各组间死亡率比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。

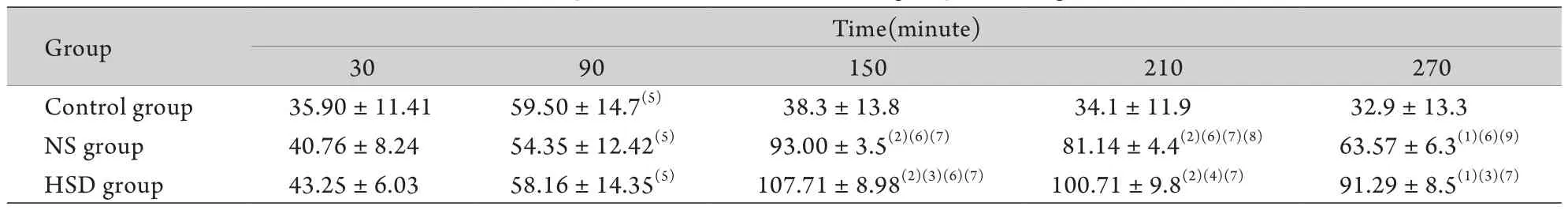

2.2大鼠MAP变化 爆炸后30min大鼠MAP低于40mmHg,停止放血后有所上升,于90min升至60mmHg左右。对照组大鼠MAP在90min后再次迅速下降,于270min降低至30mmHg左右。NS组及HSD组大鼠MAP均逐渐升高,其中HSD组升高更明显,210min及270min时相点NS组大鼠MAP存在明显下降趋势,HSD组下降不明显。在150、210、270min时间点,NS组及HSD组MAP显著高于对照组,且HSD组MAP显著高于NS组(P<0.05或P<0.01,表1)。

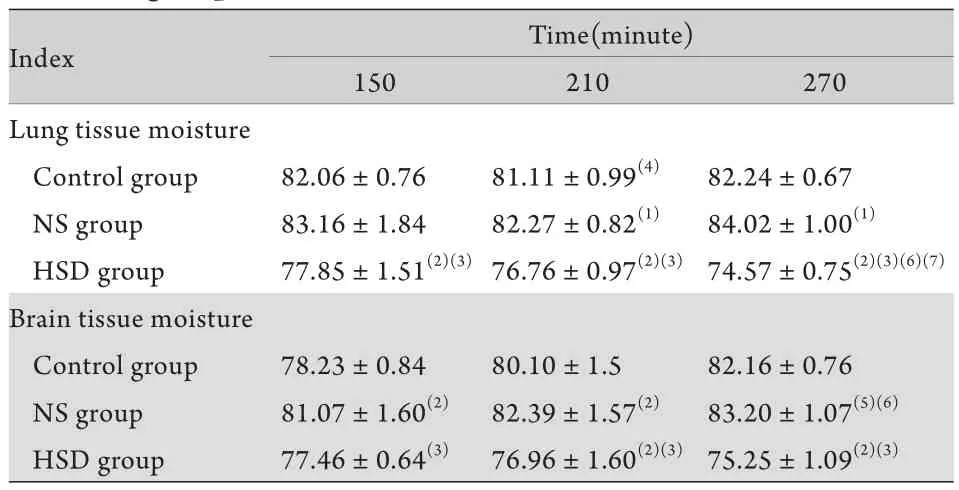

2.3各组大鼠肺、脑含水量比较 对照组大鼠肺含水量自伤后呈逐渐增高趋势,150min时为82.06%±0.76%,270min时稍增高至82.24%±0.67%。NS组大鼠肺含水量同样呈逐渐增高趋势,在伤后210、270min与对照组比较差异显著(P<0.05或P<0.01)。HSD组大鼠肺含水量在150min时轻度升高,升高程度低于对照组及NS组,210min及 270min时呈下降趋势,各时相点与对照组、NS组比较均有显著差异(P<0.01)。各组脑含水量变化趋势与肺含水量基本相同(表2)。

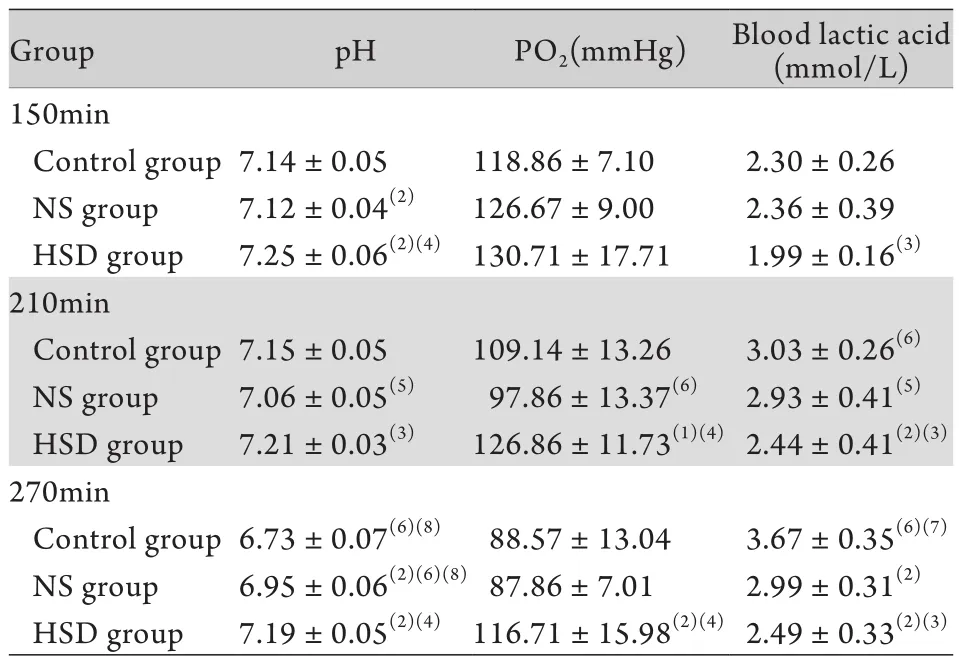

2.4各组大鼠血气指标比较 与对照组比较,虽然治疗过程中NS组及HSD组pH值、PO2整体仍呈降低趋势,血乳酸水平逐渐增高,但变化幅度明显低于对照组。在210、270min时相点,HSD组大鼠pH值、PO2均高于NS组,血乳酸则低于NS组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05或P<0.01,表3)。

表1 各组大鼠MAP值比较(mmHg,n=13)Tab. 1 Comparison of MAP in different groups (mmHg, n=13)

表2 各组大鼠肺、脑含水量比较(%,±s,n=8)Tab. 2 Comparison of brain and lung tissue moisture in different groups (%,±s, n=8)

表2 各组大鼠肺、脑含水量比较(%,±s,n=8)Tab. 2 Comparison of brain and lung tissue moisture in different groups (%,±s, n=8)

(1)P<0.05, (2)P<0.01 compared with control group; (3)P<0.01 compared with NS group; (4)P<0.05, (5)P<0.01 compared with 150min; (6)P<0.05, (7)P<0.01 compared with 210min

Index Time(minute) 150 210 270 Lung tissue moisture Control group 82.06±0.76 81.11±0.99(4) 82.24±0.67 NS group 83.16±1.84 82.27±0.82(1) 84.02±1.00(1)HSD group 77.85±1.51(2)(3)76.76±0.97(2)(3) 74.57±0.75(2)(3)(6)(7)Brain tissue moisture Control group 78.23±0.84 80.10±1.5 82.16±0.76 NS group 81.07±1.60(2) 82.39±1.57(2) 83.20±1.07(5)(6)HSD group 77.46±0.64(3) 76.96±1.60(2)(3)75.25±1.09(2)(3)

表3 各组大鼠血气指标比较(±s,n=8)Tab. 3 Comparison of blood gas index in different groups (±s, n=8)

表3 各组大鼠血气指标比较(±s,n=8)Tab. 3 Comparison of blood gas index in different groups (±s, n=8)

(1)P<0.05, (2)P<0.01 compared with control group; (3)P<0.05, (4)P<0.01 compared with NS group; (5)P<0.05, (6)P<0.01 compared with 150min; (7)P<0.05, (8)P<0.01 compared with 210min

Group pH PO2(mmHg) Blood lactic acid (mmol/L) 150min Control group7.14±0.05 118.86±7.10 2.30±0.26 NS group 7.12±0.04(2) 126.67±9.00 2.36±0.39 HSD group 7.25±0.06(2)(4)130.71±17.71 1.99±0.16(3)210min Control group7.15±0.05 109.14±13.26 3.03±0.26(6)NS group 7.06±0.05(5) 97.86±13.37(6) 2.93±0.41(5)HSD group 7.21±0.03(3) 126.86±11.73(1)(4)2.44±0.41(2)(3)270min Control group6.73±0.07(6)(8) 88.57±13.04 3.67±0.35(6)(7)NS group 6.95±0.06(2)(6)(8)87.86±7.01 2.99±0.31(2)HSD group 7.19±0.05(2)(4) 116.71±15.98(2)(4)2.49±0.33(2)(3)

3 讨 论

近年来全球范围内爆炸伤发生率不断增加,休克是爆炸伤患者死亡的重要原因之一[8-10]。休克最终会导致多脏器功能衰竭,成功实施早期容量复苏以尽快恢复血流动力学稳定性,纠正代谢紊乱,恢复组织器官的正常灌注,对休克治疗至关重要[11]。因舱室具有相对密闭的特点,密闭舱室爆炸时冲击波反射增强,肺、胃肠等空腔脏器冲击伤发生率远高于开阔地爆炸伤,若合并大量失血则血压下降快、幅度大,重要脏器血流灌注水平低[12],多器官、脏器损伤发生率高[13-14],炎症反应明显,肺、脑水肿程度进一步加重,死亡率明显增高。目前有大量关于失血性休克、感染性休克、创伤性休克液体复苏的研究,而对舱室内爆炸伤复合失血致休克患者如何进行早期液体复苏鲜见报道。

NS短时间内能有效扩充血容量,纠正钠缺失,与乳酸林格液相比,用于存在颅脑损伤的患者中可减轻脑水肿[15]。但NS单独使用时用量大,需要失液量的3~4倍才能维持有效循环[16],且过量输注会加重组织损伤[17]。HSD中的高渗成分可提高晶体渗透压,通过内源性液体转移促进组织间液及细胞液进入血管内,右旋糖酐可维持胶体渗透压,延长液体(细胞间液/细胞液)在血管内的存留时间,因此可快速恢复有效循环血量,改善微循环[18-20]。但对于舱室爆炸伤复合失血致休克患者,高渗盐溶液是否能满足治疗需求仍有待研究[21]。

本研究应用3倍失血量NS,可以在一定程度上改善循环灌注,但液体需要量大,维持循环稳定时间较短,死亡率高于HSD组,且肺、脑水肿较对照组有一定程度加重,说明NS有一定的加重肺水肿的作用,而在低海拔或平原地区,创伤失血性休克输注3~4倍失血量的平衡盐液,不会引起肺水肿和肺功能不全[22],考虑与冲击伤导致大鼠全身多脏器损伤,毛细血管通透性升高,机体对输液的耐受力降低有关。

本研究采用4ml/kg的HSD进行输注以避免大量输注后血浆氯、钠浓度升高影响酸碱平衡,导致代谢性酸中毒[23]。结果表明,HSD可明显提高大鼠存活率,升高MAP,延长血流动力学稳定时间,休克复苏后3h仍能维持较高的MAP,与既往研究结果一致[24-25],且可在一定程度上减轻肺、脑水肿,改善微循环,降低血乳酸水平,升高动脉氧分压,纠正代谢性酸中毒。虽然血液是最佳的复苏液体,但因战时环境特殊,专业医疗人员及设施缺乏,不可能将血液及血液制品用于一线治疗。HSD具有易携带、方便运输和保存、使用方法简单、作用效果强、作用时间长等特点,且能够明显减轻肺、脑水肿,即使在战场或突发爆炸伤事故现场也能在短期内实现供给,并能为转运及高级生命支持争取时间,在一定程度上满足实际医疗的需求。

综上所述,HSD维持血流动力学稳定性较持久,改善血气指标及肺、脑水肿的程度优于NS,更适用于舱室内爆炸伤复合失血致休克的大鼠早期液体复苏。

[1]Bellamy RF. The causes of death in conventional land warfare: implications for combat casualty care research[J]. Mil Med, 1984, 149(2): 55-62.

[2]Santry HP, Alam HB. Fluid resuscitation: past, present, and the future[J]. Shock, 2010, 33(3): 229-241.

[3]Bulger EM, Hoyt DB. Hypertonic resuscitation after severe injury: is it of benefit[J]? Adv Surg, 2012, 46: 73-85.

[4]Ganpule S, Alai A, Plougonven E, et al. Mechanics of blast loading on the head models in the study of traumatic brain injury using experimental and computational approaches[J]. Biomech Model Mechanobiol, 2012. [Epub ahead of print]

[5]Plurad DS. Blast injury[J]. Mil Med, 2011, 176(3): 276-282.

[6]Guy RJ, Cripps NP. Abdominal trauma in primary blast injury (Br J Surg 2011; 98: 168-179)[J]. Br J Surg, 2011, 98(7): 1033.

[7]LaCombe DM, Miller GT, Dennis JD. Primary blast injury: an EMS guide to pathophysiology, assessment & management[J]. JEMS, 2004, 29(5): 70-89.

[8]Kauvar DS, Lefering R, Wade CE. Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations[J]. J Trauma, 2006, 60(6 Suppl): S3-S11.

[9]Demetriades D, Murray J, Charalambides K, et al. Trauma fatalities: time and location of hospital deaths[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 2004, 198(1): 20-26.

[10]Acosta JA, Yang JC, Winchell RJ, et al. Lethal injuries and time to death in a level I trauma center[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 1998, 186(5): 528-533.

[11]Ertmer C, Kampmeier T, Rehberg S, et al. Fluid resuscitation in multiple trauma patients[J]. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol, 2011, 24(2): 202-208.

[12]Cui H, Xiao N, Lai XN, et al. Establishment and features of rat model of enclosed space blast injury and hemorrhage shock[J]. Acta Acad Med Mil Tert, 2010, 32(10): 1008-1011. [崔红, 肖南,赖西南. 舱室内外爆炸伤复合失血致休克大鼠伤情特点研究[J]. 第三军医大学学报, 2010, 32(10): 1008-1011.]

[13]Wolf SJ, Bebarta VS, Bonnett CJ, et al. Blast injuries[J]. Lancet, 2009, 374(9687): 405-415.

[14]Housden S. Blast injury: a case study[J]. Int Emerg Nurs, 2012, 20(3): 173-178.

[15]Schreiber MA. The use of normal saline for resuscitation in trauma[J]. J Trauma, 2011, 70(5 Suppl): S13-S14.

[16]Jin G, DeMoya MA, Duggan M, et al. Traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock: evaluation of different resuscitation strategies in a large animal model of combined insults[J]. Shock, 2012, 38(1): 49-56.

[17]Huo ZL. Fluid resuscitation and shock[J]. Int J Emerg Crit Med, 2005, 2(6): 999-1003.[霍正禄. 液体复苏与休克[J]. 世界急危重病医学杂志, 2005, 2(6): 999-1003.]

[18]Roquilly A, Mahe PJ, Lathe DD, et al. Continuous controlled-infusion of hypertonic saline solution in traumatic brain-injured patients: a 9-year retrospective study[J]. Crit Care, 2011, 15(5): R260.

[19]Banks CJ, Furyk JS. Review article: hypertonic saline use in the emergency department[J]. Emerg Med Australas, 2008, 20(4): 294-305.

[20]Sun YG, Huang ZH, Lei HY, et al. Therapeutic effect of hypertonic saline solution on traumatic shock in rats[J]. Chin J Crit Care Med, 2003, 23(6): 366-367. [孙英刚, 黄宗海, 雷洪伊, 等. 高渗氯化钠溶液对创伤性休克大鼠的治疗作用[J].中国急救医学, 2003, 23(6): 366-367.]

[21]Guo JY, Yu XQ, Lin HY. The new resuscitation strategy for hemorrhagic shock[J]. Med J Chin PLA, 2005, 30(7): 574-577. [郭剑颖, 于小千, 林洪远. 失血性休克复苏治疗进展与评价[J]. 解放军医学杂志, 2005, 30(7): 574-577.]

[22]Liu LM, Lu RQ, Lin XL, et al. Experimental study on effective fluid

resuscitation and fluid amount restriction in plateau traumatic and hemorrhagic shock[J]. Chin J Traumatol , 2000, 16(7): 428. [刘良明, 卢儒权, 林秀来, 等. 高原创伤失血性休克有效液体复苏量和限量的实验研究[J]. 中华创伤杂志, 2000, 16(7): 428.]

[23]Li T, Yang GM, Liu LM. Effect of hypertonic saline/dextran on blood gas following hemorrhagic shock in rats[J]. J Regional Anat Oper Surg, 2008, 17(1): 8-9. [李涛, 杨光明, 刘良明. 高渗氯化钠/右旋糖酐对失血性休克大鼠酸碱平衡的影响[J].局解手术学杂志, 2008, 17(1): 8-9.]

[24]Sapsford W. Hypertonic saline dextran--the fluid of choice in the resuscitation of haemorrhagic shock[J]? J R Army Med Corps, 2003, 149(2): 110-120.

[25]Sulzer JK, Whitaker AM, Molina PE. Hypertonic saline resuscitation enhances blood pressure recovery and decreases organ injury following hemorrhage in acute alcohol intoxicated rodents[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2013, 74(1): 196-202.

Fluid resuscitation in rats suffering from explosion injury in closed cabin combined with hemorrhagic shock

CUI Hong1,2, WANG Li-li1, ZHOU Min1, LAI Xi-nan1*, XIAO Nan1*

1Institute of Field Surgery, State Key Laboratory of Trauma, Burn and Combined Injury, Daping Hospital, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing 400042, China

2Department of Anesthesiology, First Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China

*

. LAI Xi-nan, E-mail: laixinan@163.com; XIAO Nan, E-mail: xiao_nan_99@yahoo.com

This work was supported by the Major Project of "Twelfth Five-Year Plan" Medical Science Development Foundation of PLA (2009BAI87B00), and the Medical and Health Research Foundation of PLA (06Z034)

ObjectiveTo compare the therapeutic efficacy of fluid resuscitation with hypertonic or normal saline on the rats suffering explosion injury in closed cabin combined with hemorrhagic shock.MethodsOne hundred and forty-seven anesthetized male SD rats undergoing explosion injury in a closed cabin where detonator was detonated instantaneously, while they were fixed at the site where the explosive was 11-12cm from the center of thoraco-abdominal junction of the rats. Smog was quickly removed from the cabin. The 10min time point after explosion was set as the zero point to record mean arterial pressure (MAP), and moderate hemorrhagic shock was conducted by uniform femoral exsanguination. One hundred and eight rats were randomly divided into three groups (36 each): control group (no resuscitation), hypertonic saline solution (HSD, 75% NaCl/6% Dextran) group (4ml/kg) and normal saline (NS) group (NS:blood loss=3:1). Fluid was given via femoral vein catheter 90min after injury, and the infusion lasted for 5min in HSD group and 30min in NS group. Eight rats were randomly sacrificed in each group at the time points of 150, 210 and 270min to analyze the arterial blood gas and water content in the brain and lung tissues. The other 39 rats were alsorandomly and equally divided into 3 groups and the treatment was the same as above, but with recording of the MAP and survival rate at the time points of 30, 90, 150, 210 and 270min.ResultsSix rats died in control group, three died in NS group, and all rats of HSD group survived up to 270min. There were significant differences in survival rate among the 3 groups. The MAP rose obviously in NS and HSD groups at the time point of 150min, while it lowered gradually at 210min and 270min in NS group, but no obvious lowering was found in HSD group, and the difference was significant at 270min among the 3 groups (P<0.05). The water contents in the lung and brain tissues decreased in HSD group but increased in NS group at 150min, 210min and 270min, and the differences were significant among the 3 groups (P<0.05 orP<0.01). Arterial blood gas improvement was detected in both HSD and NS groups. At 210min and 270min, pH and PO2were higher but lactate level was lower in HSD group than in NS group (P<0.05 orP<0.01). Conclusion HSD could maintain the hemodynamic stability of rats suffering from explosion injury combined with hemorrhagic shock, and its positive effect on arterial blood gas and edema of the lung and brain is superior to normal saline.

enclosed space blast injuries; shock, hemorrhagic; saline solution, hypertonic; fluid resuscitation

R826.56

A

0577-7402(2013)06-0512-04

2013-01-08;

2013-04-21)

(责任编辑:胡全兵)

全军“十二五”医学科研重大项目(2009BAI87B00);全军医药卫生科研基金(06Z034)

崔红,医学硕士,住院医师。主要从事创伤急救方面的基础与临床研究

400042 重庆 第三军医大学大坪医院野战外科研究所,创伤、烧伤与复合伤国家重点实验室[崔红(现在重庆医科大学附属第一医院麻醉科)、王丽丽、周敏、赖西南、肖南]

赖西南,E-mail:laixinan@163.com;肖南,E-mail:xiao_nan_99@yahoo.com