Eight-week follow-up of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis B, patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis and normal control subjects

Qinyi LIU*, Zheng LU, Lin SUN, Jun YE

· Research Article ·

Eight-week follow-up of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis B, patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis and normal control subjects

Qinyi LIU1*, Zheng LU2, Lin SUN2, Jun YE2

Background:Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) and Hepatitis B Cirrhosis (HBC) often have associated depressive and anxiety symptoms, but the relationship of these psychological symptoms to the course and severity of CHB and HBC remain unclear.Objective:Assess the changes in depressive and anxiety symptoms among patients receiving treatment for acute exacerbations of CHB and HBC.Methods:71 patients with CHB and 75 patients with HBC were enrolled at the time of admission and followed during the subsequent eight weeks of treatment. These subjects and 65 volunteer control subjects were administered the 90-item Symptom Checklist (SCL-90) on enrollment and eight weeks later; they were also administered the Hamilton Anxiety Scale(HAMA), the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Self-Rating Depression Scale(SDS) at enrollment and two, four, six and eight weeks after enrollment.Results:In each group 60 subjects completed the study. At baseline the mean SCL-90 total score, most of the SCL-90 subscale scores and the mean scores for the HAMA, HAMD, SAS and SDS were all significantly higher in patients with CHB and HBC than in the control subjects. Based on the HAMA and HAMD results, 40% of CHB patients and 80% of HBC patients had clinically significant anxiety and 78% of CHB patients and 87% of HBC patients had clinical significant depression at thetime of admission. In both patient groups total SCL-90 score and most of the SCL-90 subscale scores decreased significantly over the eight weeks of treatment; there was also a significant decline in the mean scores of the HAMA, HAMD, SAS and SDS over the first six weeks of treatment. After eight weeks of treatment 5% of CHB patients and 28% of HBC patients still had clinically significant anxiety and 7% of CHB patients and 36% of HBC patients still had clinical significant depression. At baseline and at all four follow-up assessments the severity of psychological symptoms was significantly greater in the HBC group than in the CHB group.Conclusion:Self-reported and interviewer-assessed psychological symptoms in patients with CHB and HBC are significantly more severe than in normal control subjects both at the time of acute exacerbations of the illness and after the acute symptoms have resolved. The psychological symptoms in HBC patients are more severe than those in CHB patients.Treatment of the physical symptoms of acute CHB and HBC over an eight-week period is associated with improvement—but not full resolution—of these psychological symptoms.

Chronic Hepatitis B; Hepatitis B Cirrhosis; Depression;Anxiety

1 Introduction

There are approximately 20 million individuals with Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) in China[1], 30% of whom develop Hepatitis B Cirrhosis (HBC) within 15 years of the initial diagnosis[2]. CHB and HBC are chronic,debilitating conditions that seriously affect quality life and often cause economic hardships for the affected individuals, their families and the community at large. These individuals often experience associated psychological problems, particularly depression and anxiety[3]. Studies in other countries[4,5]report a high prevalence of depression in patients with cirrhosis(up to 27%) and find that the severity of depressive symptoms varies in parallel with the severity of thehepatic disease, but there are few reports about the relationship of psychological symptoms to hepatic disease in China. The current study regularly assesses a variety of psychological symptoms over the first eight weeks of treatment in patients with CHB and HBC admitted to a general hospital in Shanghai, China.

2 Subjects and Methods

2. 1 Subjects

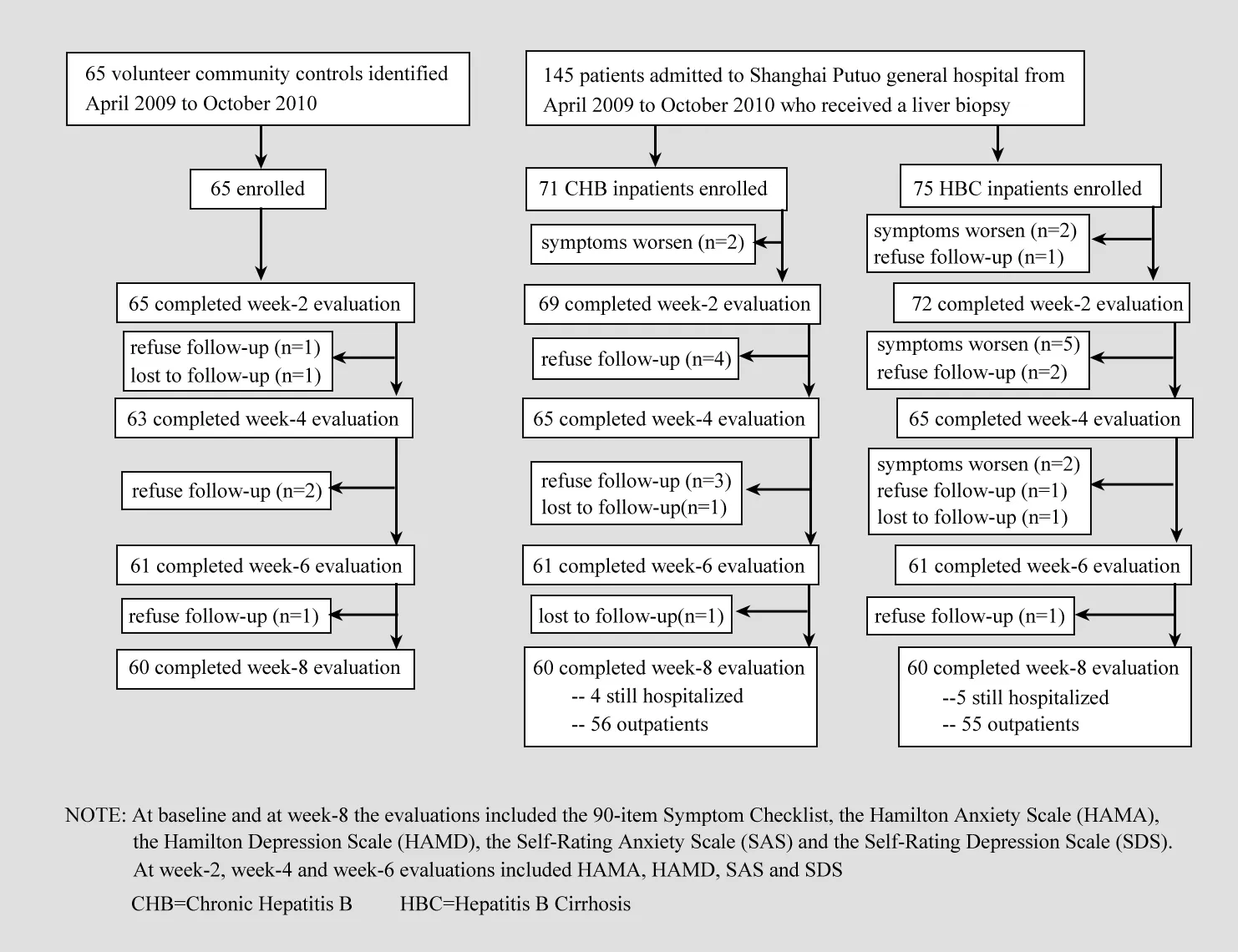

The enrolment and assessment of subjects for the study is shown in Figure 1. Patients admitted to the Departments of Infectious Diseases and Gastroenterology at the Shanghai Putuo District general hospital from April 2009 through October 2010 and who received a liver biopsy were potential subjects for the study. CHB and HBC were diagnosed based on the biopsy results: CHB was classified as mild, moderate or severe according to criteria recommended by the Chinese Medical Association[6,7]and HBC was classified as Class A, Class B or Class C based on the Child-Pugh score[6,7](Class A includes patients who are clinically compensated while Class B and Class C include patients who are clinically decompensated). Exclusion criteria were any prior treatment for a mental health problem,family history of mental illness, use of antipsychotic medications in the prior two months, less than six years of education, monthly family income of less than 3,000 renminbi ($US 462) or greater than 15,000 renminbi($US 2,308), history of major medical illness, drug or alcohol dependence, difficulty in communicating in Mandarin, and refusal to provide consent.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study

There were 71 patients enrolled in the CHB group,37 (52.1%) males and 34 (47.9%) females. Their age ranged was 36-65 years with a mean (standard deviation) value of 48.5 (9.2) years; 65 cases were married and 6 cases were unmarried; 1 case had graduated from elementary school, 26 from junior high school, 20 from high school and 24 from university;36 cases were currently employed and 35 were not;and 48 cases were classified as chronic mild CHB, 19 as moderate CHB and 4 as severe CHB. There were 75 patients enrolled in the HBC group, 45 (60.0%) males and 30 (40.0%) females. Their age ranged was 36-65 years with a mean value of 52.1 (8.7) years; 67 cases were married and 8 were unmarried; 3 cases had graduated from elementary school, 27 from junior high school, 21 from high school and 24 from university;33 cases were currently employed and 42 were not;13 cases were in a compensated state and 62 were in a decompensated state; 41 had ascities and 12 had esophageal bleeding.

The control group included 65 non-hospitalized healthy volunteers recruited from the community,including 33 (55.8%) males and 32 (49.2%) females.Their age ranged from 36-65 years with a mean value of 50.8 (8.9) years; 60 individuals were married and 5 were unmarried; 30 had graduated from junior high school, 18 from high school, and 17 from university; 27 were currently employed and 38 were not.

There were no significant differences by gender,marital status, education level, or working status among the three groups but the mean age of the HBC group was significantly greater than that of the CHB group[F-test for ANOVA for three groups=3.10 (p=0.047);posthoc Tukey test finds HBC age>CHB age (p=0.014)].

2. 2 Study methods

The baseline evaluation of the 90-item Symptom Check List (SCL-90), Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA),Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale(SDS) was conducted at the time of admission (for patients) or enrolment (for controls). After admission patients were administered standard treatments to protect the liver, decrease related enzyme levels and manage related symptoms of jaundice, gastric bleeding,ascites, and so forth[7]. The HAMA, HAMD, SAS and SDS questionnaires were re-administered two, four, six and eight weeks after starting treatment and the SCL-90 was re-administered eight weeks after enrollment.If the patient was discharged during the eight-week treatment period, the evaluations were conducted in the outpatient department or in the patient’s home.None of the subjects received pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatment for depression or anxiety at any point in the eight-week course of treatment.

2. 3 Instruments

A demographic data sheet prepared by the authors was used to obtain basic information about enrolled individuals including age, gender, marital status,occupation, educational level, economic condition,medical history, and so forth.

The Symptom Check List (SCL-90) is a self-completion scale with 90 items sub-divided into 10 subscales (see Table 1) that assess different aspects of respondents’thinking, feelings and behavior over the prior week[8].Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0-4) with higher scores representing more severe symptoms. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the SCL-90 are good[9].

The Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) is a clinicianadministered scale with 14 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0-4)[10]. The Hamilton Depression Scale(HAMD) is a clinician-administered scale with 24 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0-4). The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) is a self-report scale with 20 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1-4)[10]. The Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) is a self-report scale with 20 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1-4)[10]. The reliability and validity of the Chinese versions of these scales are satisfactory[10].

2. 4 Statistical methods

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 11.0 software[11]. The mean per-item score (range 0-4) for the total SCL-90 and for each SCL-90 subscale were used as the outcome measures for the SCL-90. Chi square tests and one-way ANOVA tests compared baseline values between the three groups, paired t-tests and McNemar tests with a continuity correction compared baseline and eight-week outcomes, and repeated measures ANOVA with post-hoc follow-up tests using Least-Squared Difference (LSD) measures[12]was used to compare changes in HAMA, HAMD, SAS and SDS scores between the CHB and HBC groups over the five time periods (baseline and two, four, six and eight weeks after starting treatment). Chi-square tests were used to compare rates of clinically significant symptoms in the three groups and a Tukey-type multiple comparison method based on an arcsin transformation of the original proportions[13]was used to make two-way comparisons. Two-tailed tests of significance were employed and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

As shown in Figure 1, sixty subjects completed the full eight weeks of follow-up in each of the three groups. The gender of the subjects who dropped out from the three groups was not different for that of those who remained until the end of the study, but the 15 subjects who dropped out from the HBC group were older than the 60 who did not drop out [58.5 (5.8) vs 50.5 (8.6) years, t=11.74, p=0.001] and the 11 subjects who dropped out of the CHB group were younger than the 60 who did not drop out [39.3 (4.0) vs 50.2 (8.8)year; t=15.90, p<0.001].

As shown in Table 1, with the sole exception of the Paranoia subscale of the SCL-90, for all other psychological measures assessed the baseline values were highest (i.e., worst) in the HBC group, intermediate in the CHB group and lowest in the control group. In almost all cases these differences between the three groups were statistically significant. In the two patient groups, with the exception of the Phobic Anxiety SCL-90 subscale in the CHB group and the Paranoia SCL-90 subscale in the HBC group, all other measures assessed showed significant improvement after eight weeks of treatment of the underlying hepatic condition.In the control group none of the measures changed significantly over the eight-week follow-up. Despite the significant improvement in symptoms, at the end of the eight weeks the two patient groups continued to have more severe symptoms than the control group and the HBC groups continued to have significantly more severe symptoms than the CHB group.

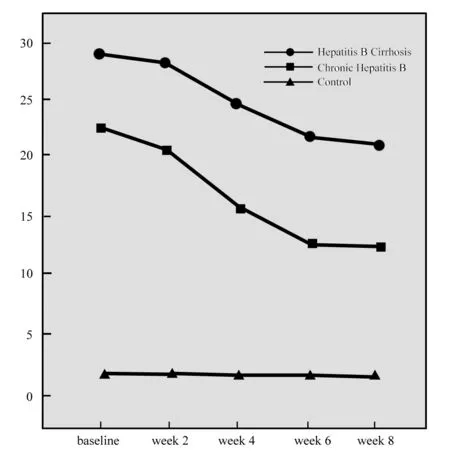

Figure 2. Hamiltion Anxiety Scale scores over 8 weeks of follow-up

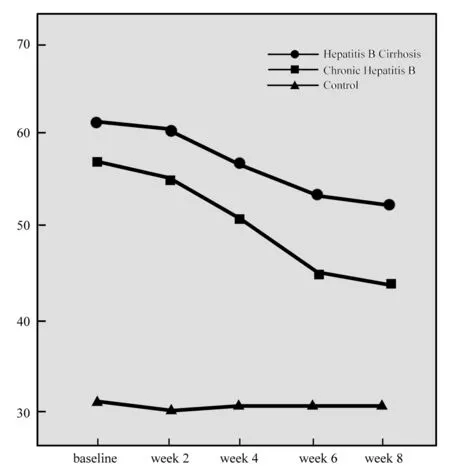

Figure 4. Hamiltion Depression Scale scores over 8 weeks of follow-up

Figure 5. Scores of the Self-Rated Depression Scale over 8 weeks of follow-up

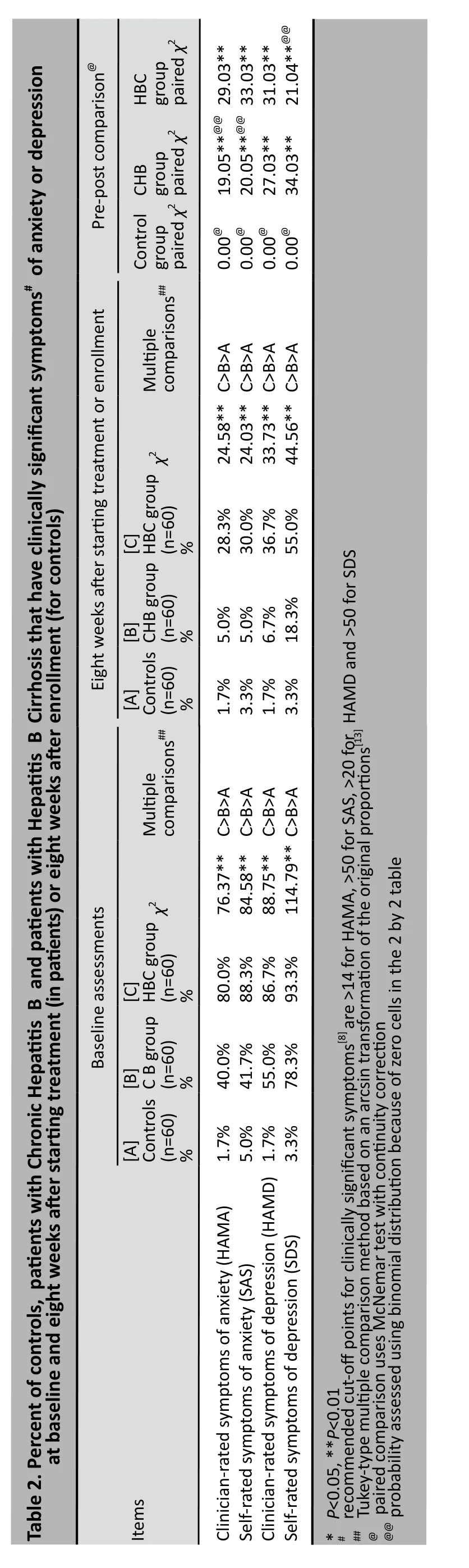

Table 2 shows the comparison of the proportion of subjects in the three groups that had clinically significant symptoms of anxiety and depression using both clinician-based measures and self-report measures at baseline and eight weeks after the baseline assessment. Similar to the pattern for the continuous scores, HBC patients were more likely to have clinically significant symptoms than CHB patients and both patient groups were more likely to have clinically significant symptoms than the subjects in the control group. Despite significant decreases in the proportions of patients with clinically significant symptoms after eight weeks of treatment, the proportions of patients with clinically significant symptoms at the end of the eight weeks of treatment remained significantly higher than that in the control group.

The correlation and concordance of the clinician rated and self-report measures was quite high.Combining both the baseline and eight-week results,the correlation of HAMA and SAS scores was 0.91(p<0.001) (Spearman correlation) and the concordance of the classification as clinically significant anxiety symptoms was 0.82 (Kappa). The correlation of HAMD and SDS scores was 0.94 (p<0.001) (Spearman correlation) and the concordance of the classification as clinically significant depressive symptoms was 0.79(Kappa).

Figures 2-5 show the changes in HAMA, SAS,HAMD, SDS in the two patient groups and the control group over the eight-week follow-up period. Repeated measures ANOVA found that for all four measures in both groups there is a significant drop in the mean score over the eight weeks of treatment but the decline was not constant over time; the drop from baseline in the first two weeks of treatment was not statistically significant, the drop from week 2 to week 4 and the drop from week 4 to week 6 was statistically significant,and the drop from week 6 to week 8 was not statistically significant. The HBC mean scores are significantly lower than the CHB scores at all time periods. However, the rate of change in the scores between the two patient groups is not significantly different.

For all four measures of anxiety and depression the repeated-measures ANOVA found that the time effect and the group effect were statistically significant but the timeXgroup interaction term was not statistically significant. For HAMA the F-values for the time effect,the group effect and the interaction effect were F=329.27 (p<0.001), F=51.23 (p<0.001), and F=1.02(p=0.358), respectively. The corresponding values for SAS were F=270.59 (p<0.001), F=40.27(p<0.001), and F=2.01 (p=0.137). For HAMD the corresponding values were F=303.55 (p<0.001), F=49.60 (p<0.001), and F=1.10 (p=0.330). For SDS the corresponding values were F=392.27 (p<0.001), F=18.48 (p<0.001) and F=4.84(p=0.070).

4 Discussion

4. 1 Main findings

The present study confirms previous studies in China[14]and elsewhere[3]that report a wide range of psychological symptoms in patients with CHB and HBC. Our SCL-90 findings indicate that individuals with acute exacerbations of chronic hepatitis show elevated measures on almost all types of psychological symptoms. At the time of hospitalization clinicianrated scales find clinically significant anxiety in 40% of CHB patients and 80% of HBC patients and clinically significant depression in 78% of CHB patients and 87%of HBC patients. These psychological symptoms improve significantly over an eight-week course of treatment for the hepatitis (without specific treatment focused on the psychological symptoms) but even after the physical symptoms are stabilized substantial psychopathology remains, particularly in the HBC group. After eight weeks of treatment for hepatitis the prevalence of clinically significant anxiety and depression in the CHB group are 5% and 7%, respectively; the corresponding values in the HBC group are 28% and 36%. The greater severity of psychological symptoms in the HBC group compared to the CHB group seen at baseline persisted throughout the eight weeks of treatment for the hepatiis.

We also found that for both groups of patients that there was little change in the level of anxiety and depression over the first two weeks of treatment for the hepatitis, a rapid improvement in the psychological symptoms from the second to sixth week of treatment and then a slower, non-significant improvement from the sixth to eight week of treatment (by which point most of the patients had been discharged from the hospital and were being treated as outpatients). This suggests that the psychological impact of the acute symptoms resolves after about six weeks of treatment and the patient returns to the ‘stable’ psychological state of non-acute, chronic hepatitis. A minority of these patients continue to have clinically significant symptoms after acute treatment for hepatitis. Thus it might be advisable to wait until the acute symptoms of hepatitis have resolved before deciding which patients with CHB or HBC merit psychological or pharmacological treatment for their associated psychological symptoms.

4. 2 Limitations

Several issues need to be considered when interpreting these results. One difference between the patient groups and the control group that was not adjusted for was the inpatient versus outpatient status of the patient at the time of the evaluation, a factor that could, in itself, affect the psychological status of the patients. Moreover, many patients were discharged over the eight-week treatment period so some to the psychological improvement they showed may have been due to returning home, not due to changes in their clinical condition. The subjects who dropped out over the eight weeks of follow-up had different mean ages than those who remained in the study so this may have biased the results; use of a ‘Last Observed value Carried Forward (LOCF)’ methodology may have had a slightly different final conclusion. The measures of severity of CHB and HBC used were rather crude (three levels) and were only assessed at the time of admission so we were unable to accurately assess the correlation of the change in the severity of hepatitis symptoms and the change in the severity of psychological symptoms.No formal assessment of the psychiatric diagnosis was undertaken so it is unclear how many of the subjects met diagnostic criteria of a mental disorder that would justify psychological of pharmacological treatment.And the improvement in psychological symptoms as acute exacerbations of chronic hepatitis resolve that we identified does not provide information about the psychological status and psychological treatment needs of CHB and HBC patients who are in chronic residual states. Longer follow-up of community-based CHB and HBC patients will be needed to assess these issues.

4. 3 Implications

Patients with acute exacerbations of chronic hepatitis have a wide range of associated psychological symptoms. Treatment of the symptoms of acute exacerbations of chronic hepatitis and the associated cirrhosis results in a relatively rapid improvement in these psychological symptoms, but substantial psychological symptoms remain even after the acute hepatic symptoms have resolved. Some studies have shown improvements in the quality of life of such patients when psychological and pharmacological treatments for anxiety or depression are combined with the treatment regimens for the hepatitis[15-18],but further studies that include formal diagnostic assessments of subjects are needed to determine the appropriate time for initiating adjunctive treatments for psychological symptoms (during acute or residual phases of the hepatitis) and the appropriate duration of such treatments.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding

The study was funded by the Internal Medicine Department of the Pudong District Central Hospital.

1. Lu FM, Zhuang H. Management of hepatitis B in China. Chin Med J (Engl), 2009, 122(1):3-4.

2. Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Chen CJ. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology, 2006, 130(3):678-686.

3. Bianchi G, Marchesini G, Nicolino F,Graziani R, Sgarbi D,Loguercio C, et al. Psychological status and depression in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis, 2005, 37(8):593-600.

4. Project for the Prevention and Treatment of Viral Hepatitis.Chinese Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2001, 18(1):52-62. (in Chinese)

5. Sinqh N, Gayowsk T. Depression in patients with cirrhosis:impact on outcome. Dig Dis Sci, 1997, 42(7):1421-1427.

6. Banas A, Korczak A, Lemanska M. Psychoorganic and depressive syndrome in severe hepatic diseases. Psychiatric Pol, 1995,29(4):503-512.

7. Chronic hepatitis B preventing and treatment guideline. Chinese Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2005, 23(6):421-431. (in Chinese)

8. Zhang MY. Psychiatric rating scale manual. Changsha:Hunan Science and Technology Press, 2003:17-20, 121-127, 133-137,35-42. (in Chinese)

9. Chen SL, Li LJ. Reliability, validity and norms for SCL-90. Chinese J of Nervous and Mental Diseases 2003, 29(5):323-327.

10. Zhang ZJ. Handbook of behavioral medicine Scale. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 2005:213-214, 223, 225.(in Chinese)

11. Zhang WT. SPSS 11.0 statistical analysis tutorial (Advanced).Beijing Hope Electronic Press, 2002:32-63.

12. Chen PY. Analysis of variance of repeated measure data. Chinese Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 2003, 5(1):67-70. (in Chinese)

13. Zar HG. Biostatistical analysis. 4th Edition. Prentice Hall:New Jersey, 1999:563-565.

14. Lei QL, Zhao ZX, Huang YX, Wen QS, Liu ZX. Mental health status in patients with liver cirrhosis after hepatitis. Journal of The Fourth Military Medical University, 2001, 22(9):849-851. (in Chinese)

15. Zhang Y, Zhou JJ, Wang YM. Effects of psychotherapy on depression and anxiety of patients with chronic hepatitis B:a meta-analysis. World Chinese Journal of Digestology, 2008,16(1):101-104. (in Chinese)

16. Kim SH, Oh EG, Lee WH. Symptom experience, psychological distress, and quality of life in Korean patients with liver cirrhosis:a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud, 2006,43(8):1047-1056.

17. Sharif F, Mohebbi S, Tabatabaee HR, Saberi-Firoozi M,Gholamzadeh S. Effects of psycho-educational intervention on health-related quality of life (QOL) of patients with chronic liver disease referring to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2005, (3):81.

18. Zandi M, Adib-Hajbagheri M, Memarian R, Nejhad AK, Alavian SM. Effects of a self-care program on quality of life of cirrhotic patients referring to Tehran Hepatitis Center. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2005, (3):35.

慢性乙肝、乙肝后肝硬化患者及正常对照组随访8周的抑郁和焦虑症状

刘沁毅1陆 峥2孙 琳2叶 军2

1上海市普陀区中心医院200062;2上海市同济医院200065。通信作者:刘沁毅,电子信箱:13761284552@139.com

背景慢性乙肝(Chronic Hepatitis B,CHB)和乙肝后肝硬化(Hepatitis B Cirrhosis,HBC)患者经常伴发抑郁、焦虑症状,但病程进展中的心理状况和CHB、HBC患者的病情之间的关系尚不清楚。

目的对住院治疗的CHB和HBC急性发作患者的抑郁和焦虑症状的变化进行评估。

方法对71例CHB和75例HBC患者在入院治疗时进行测评,其后治疗期间随访8周。同时,以健康志愿者65人作对照组。分别对3组对象在入院时和随访第8周时进行90项症状自评量表(Symptom Check List-90,SCL-90)测评。 采用汉密尔顿焦虑量表(Hamilton Anxiety Scale,HAMA)、汉密尔顿抑郁量表(Hamilton Depression Scale,HAMD)、焦虑自评量表(Self-Rating Anxiety Scale,SAS)及抑郁自评量表(Self-Rating Depression Scale,SDS)分别对3组研究对象每隔2周,即入院时、随访第2周、第4周、第6周、第8周时进行评定。

结果每组均有60例对象完成测评。CHB组和HBC组的基线SCL-90总均分、大部分SCL-90因子分、HAMA、HAMD、SAS及SDS评分的均分均高于健康对照组。HAMA、HAMD评定显示,在入院时40%的CHB和80%的HBC患者有明显焦虑症状,78%的CHB和87%的HBC患者有明显的抑郁。治疗8周后,两组患者的SCL-90总均分、大部分SCL-90因子分均显著下降。治疗6周后,两组患者的HAMA、HAMD、SAS及SDS评分的均分也显著下降。治疗8周后,5%的CHB和28%的HBC患者仍有明显焦虑,7%的CHB和36%的HBC患者有明显抑郁。基线和4次测评分均提示,HBC组比CHB组患者的心理症状严重。

结论在CHB、HBC患者急性发作入院时和经临床治疗急性症状缓解后,两组患者自评、他评的心理症状均比健康对照组严重。HBC组比CHB组患者的心理症状更严重。对急性发作的CHB、HBC患者的躯体症状治疗8周后,其心理症状也可改善,但并不能完全消除。

慢性乙肝 乙肝后肝硬化 抑郁 焦虑

10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2011.06.004

1Shanghai Putuo District Central Hospital, Shanghai 200062, China

2Shanghai Tongji Hospital, Shanghai 200065, China.

* Correspondence: 13761284552@139. com

(received: 2011-03-04; accepted: 2011-09-07)

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- Mental health literacy in Changsha, China

- Relationship between blood levels and clinical efficacy of two different formulations of venlafaxine in female patients with depression

- Cost of treating medical conditions in psychiatric inpatients in Zhejiang, China

- 苯丙胺类兴奋剂所致精神障碍的临床诊治问题

- Biostatistics in Psychiatry (6)Estimating treatment effects in observational studies

- Management of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)—no easy solution