Cost of treating medical conditions in psychiatric inpatients in Zhejiang, China

Shengliang YANG*, Mincai QIAN, Wei LU, Chunsheng WANG, Haizhi CHEN, Jinfeng FEI, Xinhua SHEN,Jianhong YANG

· Research Article ·

Cost of treating medical conditions in psychiatric inpatients in Zhejiang, China

Shengliang YANG1*, Mincai QIAN1, Wei LU1, Chunsheng WANG2, Haizhi CHEN1, Jinfeng FEI1, Xinhua SHEN1,Jianhong YANG1

Background:Few studies in China assess the relative costs of treating psychiatric and non-psychiatric medical conditions among psychiatric patients. This information is important for the planning of mental health services and of health insurance packages.Objective:Assess the breakdown of the 2010 costs of psychiatric inpatient care in a representative sample of psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang Province, China.Methods:A two-stage strati fied sampling method was used to select 14 of the 42 psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang and then discharges for three randomly selected months (March, July and November) in 2010 at these hospitals were selected for assessment. A standardized form was used to collect information about the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients and about the various components of the costs of inpatient care.Results:7,684 inpatient admissions were included. The median (interquartile range) length of stay was 30 (20-52) days and the median total cost of admission was 10,005 (6,419-14,728) Chinese Yuan (1,539 $US). The median cost of medication was 2,512 (1,161-4,182) Yuan, 65% of which was for non-psychiatric medications. 1,798 (24.3%) of the admissions had one or more co-morbid medical condition that required treatment, including hypertension, leucopenia, diabetes and different types of infections. The prevalence and type of medical condition varied significantly for patients with different classes of psychiatric diagnoses. After adjustment for other factors the presence of a co-morbid medical condition significantly increased the cost of hospitalization but not the duration of hospitalization. For inpatients with schizophrenia the cost of their psychiatric medications was significantly higher than the cost of their non-psychiatric medications but the opposite was true for patients with other diagnoses.Conclusion:Treatment of somatic conditions account for a high proportion of the cost of inpatient treatment in psychiatric hospitals. Plans to revise the reimbursement mechanisms for mental disorders, to develop diagnostic-related group payment schemes, and to establish diagnostic-specific treatment guidelines need to take into consideration the high prevalence and associated costs of treating somatic conditions that frequently accompany psychiatric illnesses. And the in-service training of psychiatrists needs to ensure that they are up-to-date on recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of common physical disorders.

Psychiatric disease; Medical cost; Complication; Survey

1 Introduction

The morbidity and mortality of somatic diseases in psychiatric patients, particularly those with schizophrenia, are higher than in the community at large[1]. These physical conditions greatly increase the burden of psychiatric illnesses and the cost of treating individuals with psychiatric disorders. But there are very few studies about the relative costs of treating the psychiatric and physical problems of psychiatric patients[2,3]. Information about the costs associated with treating the medical illnesses of psychiatric patients is essential to the planning and funding of psychiatric services, and will become increasingly important in the coming years as China undergoes major medical reforms aimed at transferring the care of many individuals with psychiatric problems from specialty hospitals to community health services. To help clarify this issue the present study estimates the proportion of psychiatric inpatients treated in specialty hospitals inZhejiang Province in 2010 who had co-morbid physical illnesses that required treatment while hospitalized for their psychiatric condition. The study also compares the total costs and the psychiatric and non-psychiatric medication costs of different groups of psychiatric patients.

2 Subjects and Methods

2. 1 Subjects

The sampling frame for this investigation included all patientswith any diagnosis in the Chinese Classi fication of Mental Disorders[4]who were discharged from specialty psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang Province in 2010.

2. 2 Methods

2. 2. 1 Identification of the sample

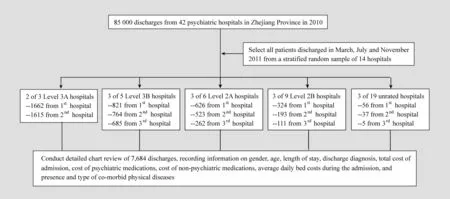

The sample selection process is shown in Figure 1.Psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang are graded based on the number of beds and number of outpatients. There are 42 specialty psychiatric hospitals in the province,including three Level 3A hospitals (the largest and most advanced hospitals), five level 3B hospitals, six level 2A hospitals, 9 level 2B hospitals, and 19 unrated hospitals (the smallest hospitals). Fourteen of the 42 hospitals were randomly selected, including two level 3A, three level 3B, three level 2A, three level 2B and three unranked hospitals. Three months in the year were randomly selected (March, July and November)and 7,684 discharges in 2010 from these 14 hospitals in those three months were considered in the analysis.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the identification of cases

2. 2. 2 Survey tool

A preliminary data collection instrument (to be completed when reviewing patients’ charts) was developed in consultation with experts and leaders at each participating hospital. This instrument was pretested on 3,117 charts of patients discharged from the Third People’s Hospital of Huzhou City and then revised accordingly. The instrument includes the following items:gender, age, length of stay, discharge diagnosis, total cost of admission, cost of psychiatric medications, cost of non-psychiatric medications,average daily bed costs during the admission, and presence and type of co-morbid physical diseases that required medical treatment during the admission. At each hospital the instrument was completed by two or three attending-level physicians who were trained to complete the instrument.

2. 3 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 11.5 software.Hospital costs are not normally distributed so median costs and the associated interquartile ranges (i.e.,IQR=25%-75% range) are reported. The discharge diagnoses were divided into five main groups: mood disorders; schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders;hysteria, stress-related and neurotic disorders; organic mental disorders; and substance-induced disorders.Comparison of costs across groups are made using Mann-Whitney tests (for two groups) or Kruskal Wallis tests (for three or more groups). If three or more groups are significantly different, pairwise comparisons of groups use a multiple comparison method based on a transformation of the median ranks in each group[5]. Comparison of psychiatric drug costs and non-psychiatric drug costs (in the same patients) use Wilcoxon signed rank tests. Multiple regression models identified factors most relevant to the duration and per-day cost of admission; normal transformations of the rank of the duration of admission and the rank of the per-day cost were the dependent variables in the regression models.

3 Results

3. 1 General information about the discharges

The 7,684 discharges assessed included 3,102(40.4%) discharges in males and 4,582 (59.6%)discharges in females. The mean (SD) age of these subjects at admission was 43.4 (16.8). Their median(IQR) length of stay was 30 (20-52) days. The primary discharge diagnosis was a mood disorder in 34.6% of the discharges, a psychotic disorder in 40.6%, a neurotic disorder (including hysteria and stress-related disorders)in 14.1%, an organic mental disorder in 5.6%, and a substance-induced disorder in 2.0%. The median (IQR)duration of admission was 28 (20-41) days in the mood disorders group, 45 (26-84) days in psychotic disorders group, 25 (19-32) days in the neurotic disorders group,25 (13-40) days in the organic mental disorders group,and 18 (11-35) days in the substance-induced disorders group.

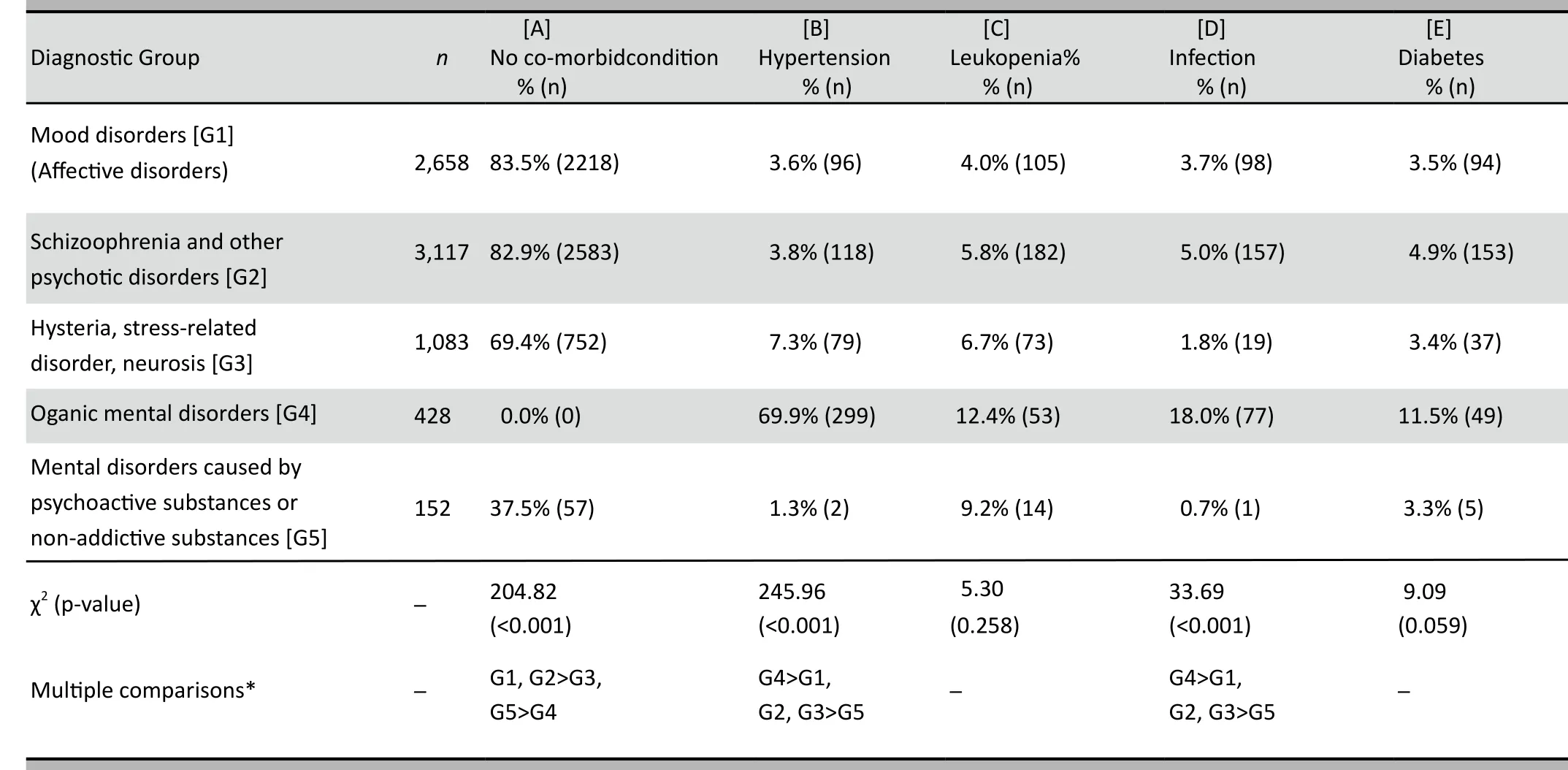

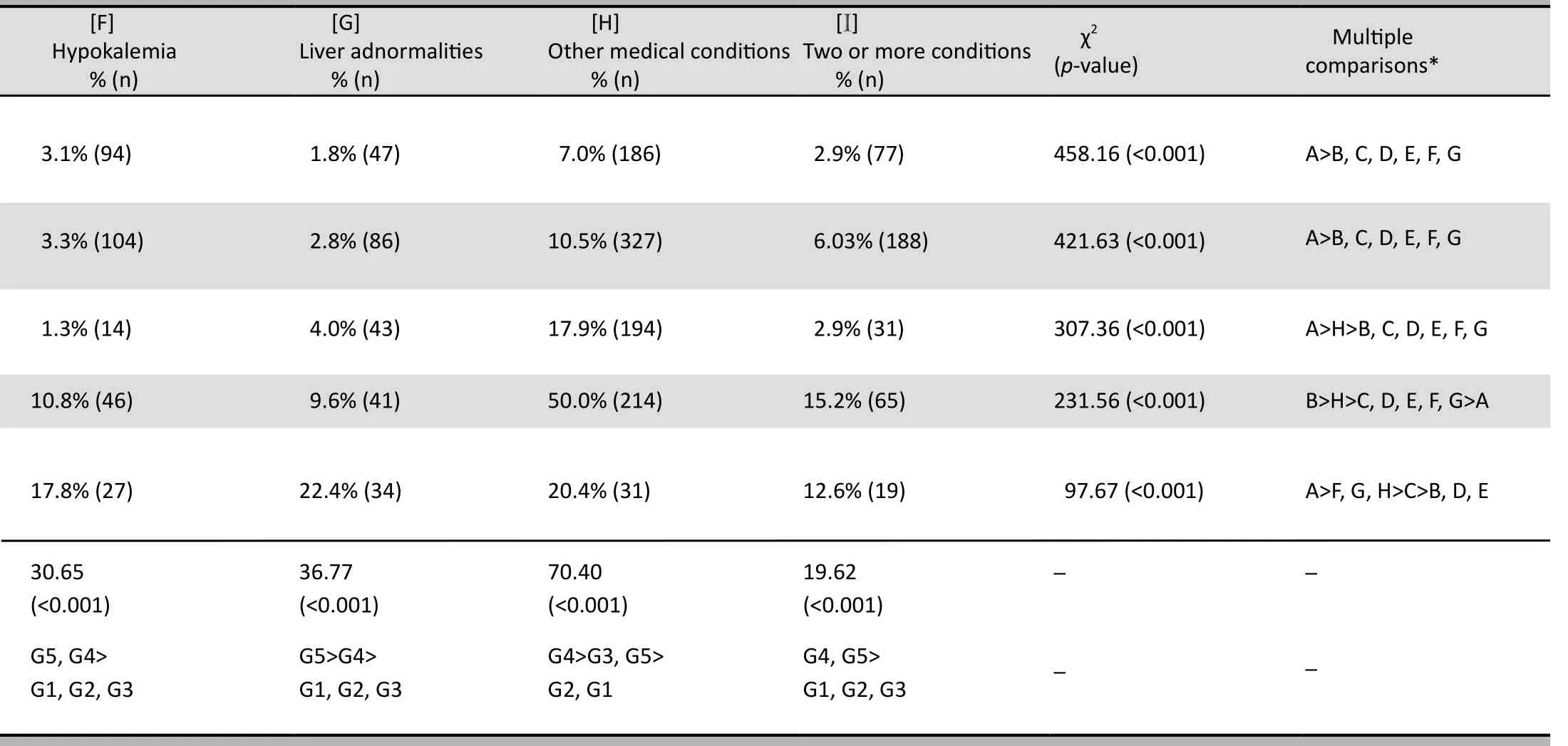

3. 2 Co-morbid medical conditions

Co-morbid medical conditions that required treatment during the 7,684 hospitalizations were hypertension (7.7%), leucopenia (5.6%), different types of infections (4.6%), diabetes (4.4%), hypokalemia(3.6%), liver abnormalities (3.3%) and other conditions(5.4%). In total 24.3% of the admissions had one or more medical condition that required treatment during the admission; 4.9% had two or more medical conditions that required treatment. As shown in Table 1,the proportions of admissions that required treatment for medical conditions varied by psychiatric diagnosis:100% of admissions with organic medical disorders,62.5% of admissions with substance-induced mental disorders, 30.6% of admissions for neuroses, 17.1%of admissions for psychotic disorders, and 16.5% of admissions for mood disorders had medical conditions that needed treatment. The most common types of medical conditions experienced by these psychiatric patients also varied by diagnostic group: hypotension and infections were most common in patients with organic mental disorders and least common in patients with substance-induced disorders; hyperkalemia and liver abnormalities were more common in patients with substance-induced disorders and organic mental disorders. However, the prevalence of leucopenia and diabetes was not significantly different across the five diagnostic groups.

3. 3 Composition of inpatients costs

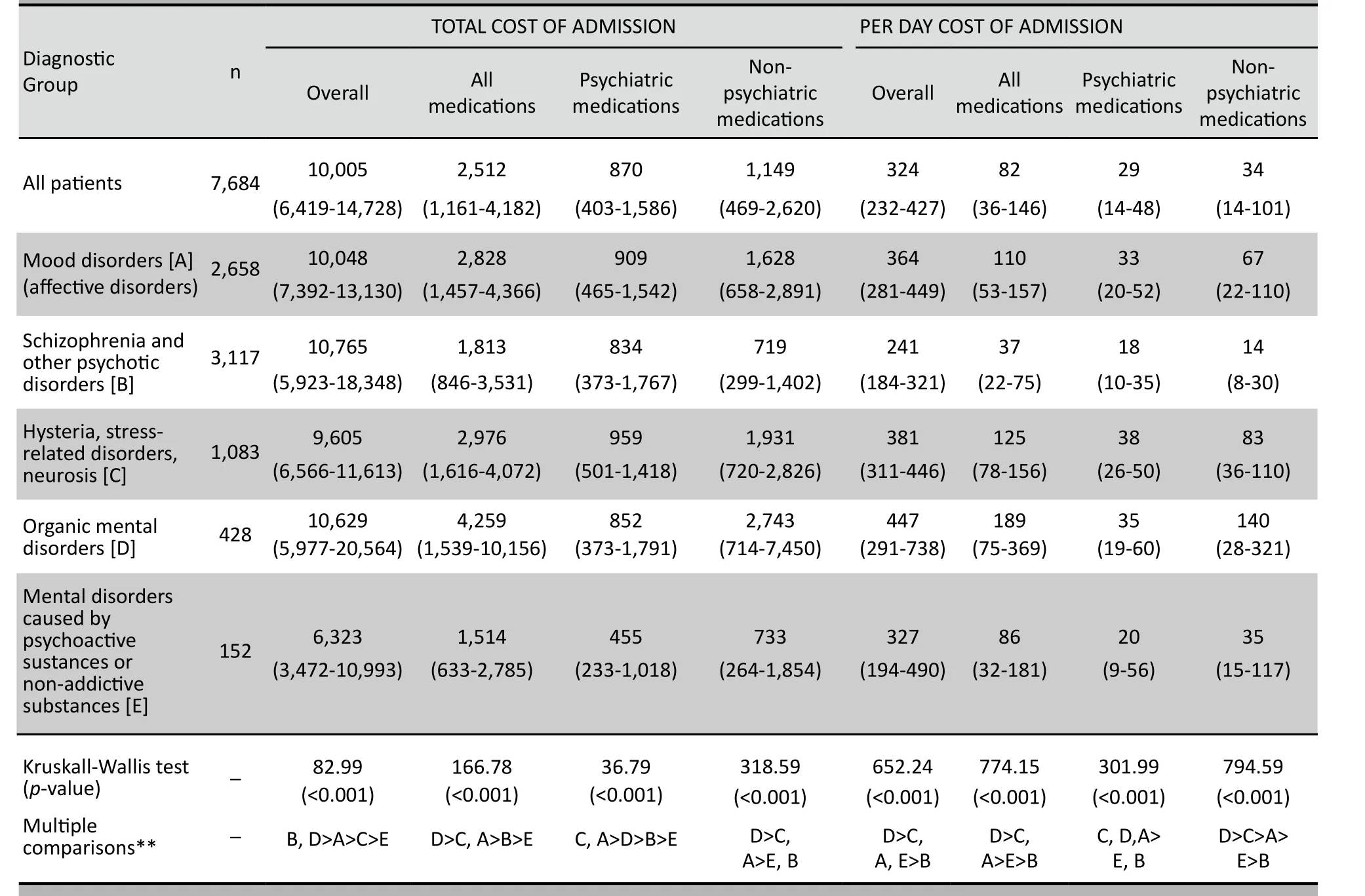

The median (IQR) cost of admission was 10,005(6,419-14,728) Yuan which is equivalent to about$1,539 ($US). The breakdown of these costs by discharge diagnosis is shown in Table 2. The per-day cost and medication costs are highest for patients with organic mental disorders and lowest for patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.Surprisingly, the per-day cost of psychiatric medication is lowest for patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. The per-day cost of non-psychiatric medication is significantly different across the five diagnostic groups: patients with organic mental disorders have the highest daily cost for non-psychiatric medications, followed by patients with neuroses, mood disorders, substance-induced disorders, and psychotic disorders.

For patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders the per-day and total costs of psychiatric medication are significantly greater than the perday and total costs of non-psychiatric medication[Z-values for Wilcoxon signed rank tests are 3.67(p<0.001) and 3.03 (p=0.002), respectively] but for the four other diagnostic groups the per-day and total costs of non-psychiatric medications are significantly higher than those for psychiatric medications (all p-values <0.001). For all of the admissions considered together (combining the five diagnostic groups) the per-day and total costs of non-psychiatric medications were significantly higher than those for psychiatric medications.

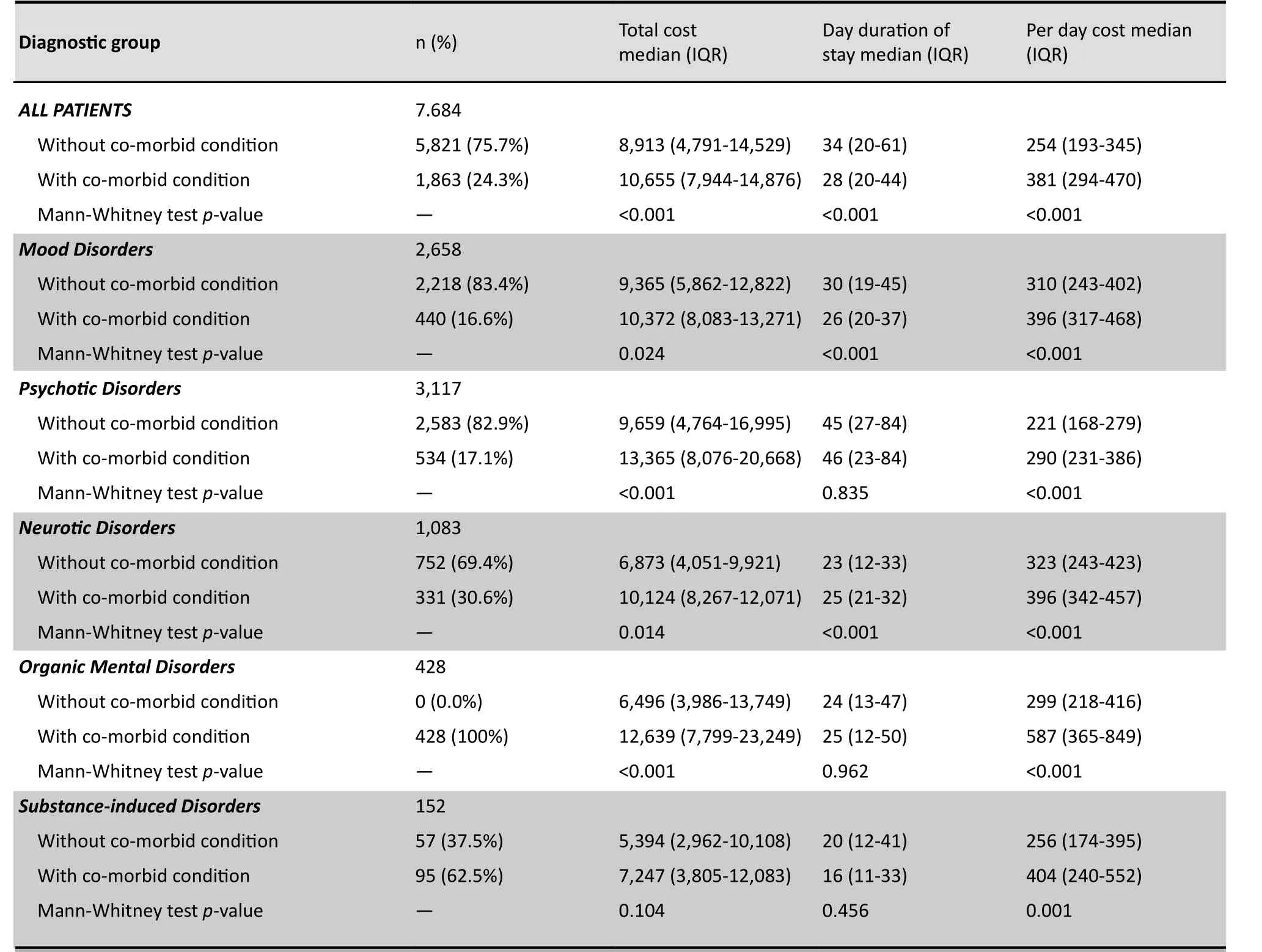

Table 3 compares the costs and duration of hospitalization of patients with and without co-morbid medical conditions within the five diagnostic groups.With the exception of discharges for substance-induced disorders, patients with any of the other psychiatric diagnoses that had co-morbid medical conditions had significantly higher total hospitals costs than those that did not have co-morbid medical conditions. Co-morbid medical conditions were associated with longer hospital stays in patients with mood disorders and neurotic disorders but were unrelated to the duration of admission in patients with psychotic disorders, organic mental disorders or substance-induced disorders. In all diagnostic groups the per-day cost of admission was higher in patients with co-morbid medical conditions.

3. 4 Predictors of duration of admission and per-day costs of hospitalization

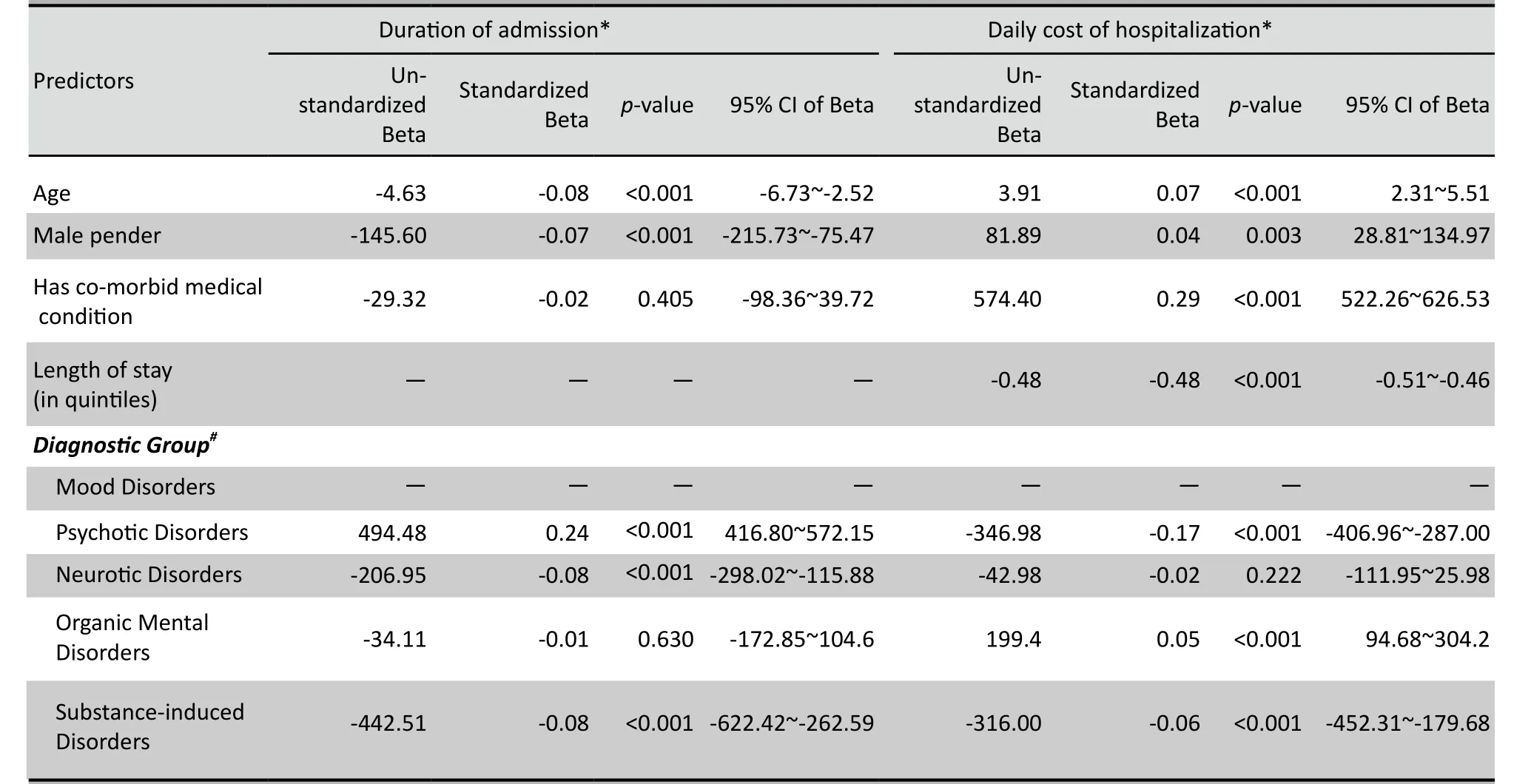

Table 4 shows the results of multiple regression equations used to identify the independent predictors of the duration of admission and per-day cost of hospitalization. Compared to patients with mood disorders, patients with psychotic disorders had longer admissions and patients with organic mental disorders or substance abuse disorders had shorter admissions;after adjusting for diagnostic group, younger patients and female patients had longer admissions; and after adjusting for diagnostic group, age and gender thepresence of a co-morbid medical condition was not significantly related to the duration of admission.Compared to patients with mood disorders, those with psychotic disorders and substance-induced disorders had lower per-day costs while those with organic mental disorders had higher per-day costs. After adjusting for diagnostic group, per-day costs increased with age, decreased with duration of admission, was higher in males, and was higher in patients who had comorbid medical conditions.

Table 1. Proportion of discharged psychiatric patients that experience different types of co-corbid medical conditions during their admis

4 Discussion

4.1 Main findings

This survey of a large, representative sample of discharges from psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang Province in 2010 has several key findings. One-quarter of all psychiatric inpatients have somatic illnesses that require treatment during the hospitalization for their psychiatric condition. The prevalence of somatic illnesses varies greatly depending on the type of psychiatric condition. The cost of hospitalization is substantially higher in patients that have comorbid somatic disorders but after adjustment for other factors the duration of hospitalization is not significantly different between those with and without co-morbid somatic illnesses. For non-psychotic disorders the costs of non-psychiatric medications during the hospitalization if greater than the cost of psychiatric medications. This information is useful for the budgeting of mental health services, for the organization of reimbursement schedules and health insurance benefits, for developing strategies to contain costs, and for determining the training needs of mental health providers.

Consistent with other studies in China[6]we found that hypertension (7.7%) and diabetes (4.4%) were more prevalent in psychiatric inpatients than among community members[7]. Leukopenia (5.6%) was also relatively common in these psychiatric inpatients.Interestingly, the prevalence of diabetes and leucopenia did not vary significantly across diagnostic groups so the presumed higher use of antipsychotic medications in patients with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia was not associated with a higher prevalence of diabetes or leucopenia. (But these results were not adjusted for gender or age so that may have obscured higher age-and gender-adjusted prevalence in the psychotic disorders group.)

These results confirm previous reports of high rates of somatic illness in patients with psychiatric disorders[1,8]and, thus, their need for high-quality medical care in addition to the need for high-quality psychiatric care. The complicated interaction between psychiatric and somatic illness—exacerbated bythe short-term and long-term side-effects of many psychiatric medications—highlights the need for psychiatrists and other mental health professionals to be up-to-date on the current guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of common medical illnesses and, importantly, on the potential interactions between psychiatric and non-psychiatric medications.

in 14 representative psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang Province, China in 2010

Cost containment for the inpatient treatment of mental disorders in China must focus on reducing the relatively long median stay (30 days for all patients and 45 days for patients with schizophrenia), limiting the occurrence of complications during hospitalization,and reducing the number and costs of the tests and medications provided during hospitalization. Similar to other studies[9]we found that the composition of inpatient costs varied by diagnostic group. The total cost for treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders was higher than that of other disorders but the per-day inpatient cost of treating schizophrenia was lower than the per-day cost of any of the other groups of disorders; so the driving force in the high cost of treating schizophrenia is the duration of admission. We also found that after adjusting for the diagnostic group the presence of a co-morbid somatic disease did not significantly increase the duration of admission. Thus the main focus on reducing the duration of psychiatric admissions needs to be on providing high-quality community based services that will make it possible to discharge patients after their acute psychiatric symptoms have resolved.

Similar to other studies in China[10,11]we found that the presence of a co-morbid somatic illness increases the cost of inpatient treatment for all psychiatric patients except for those discharged with a diagnosis of substance-induced mental disorders. Some of these somatic conditions are chronic conditions(e.g., hypertension, diabetes) that existed prior to the hospitalization and others are more often acute conditions that occur during the hospitalization (e.g.,leucopenia, hypokalemia), perhaps as a side-effect of the psychiatric treatment. There are two approaches to reducing these costs. The first it to determine if the diagnosis, tests, and medications provided for the somatic conditions in the psychiatric hospital are appropriate and, if not, to make necessary adjustments.The second is to improve the medical care of chronic somatic conditions in psychiatric patients in the community so that the costs for treating these common somatic conditions when the individual enters hospital for treatment of a psychiatric problem are reduced.

Psychiatric inpatients without identified somatic disorders also received non-psychiatric medications(analysis not provided in this paper) so this is another area where it may be possible to reduce costs. More study is needed to determine whether or not thesetreatments—often expensive Chinese traditional medications—can can be eliminated.

Table 2. The median (interquartile range) cost of inpatient psychiatric care in 14 representative psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang Province,China in 2010 (Yuan*)

4.2 Limitations

Several factors need to be considered in interpreting these results. Zhejiang is a relatively wealthy province that has a more extensive mental health care system than some other parts of the country so our results may not apply to all of China. We did not collect information on the details of the treatments provided for different types of medical conditions so it is not possible to determine the extent to which the treatments provided were appropriate. Nor were we able to identify the relationship between the use of different types of psychiatric medications and potential medical complications, such as the relationship between clozapine use and leucopenia. Some of the differences in prevalence of the medical conditions in the different diagnostic groups may have been due to differences in gender and age that were not adjusted for in the analysis. Unfortunately, the data collected did not include the specific hospital of each discharge so it was not possible to include the level of hospital in the analysis; this is one factor that could have influenced both the duration of hospitalization and the costs of treatment. And we did not assess the costs of nonpsychiatric medications in psychiatric patients who did not have identified medical conditions.

4.3 Implications

The rapidly increasing costs of hospitalization for mental disorders has serious consequences for patients,their families and the overall health budget. The high proportion of inpatient costs used for the treatment of non-psychiatric conditions suggests that this is one possible target for cost containment. Plans to revise the reimbursement mechanisms for mental disorders,to develop diagnostic-related group payment schemes,and to establish diagnostic-specific treatment guidelines need to take into consideration the high prevalenceand associated costs of treating somatic conditions that frequently accompany psychiatric illnesses[12,13].

Table 3. Comparison of total cost of admission (in Chinese Yuan*), duration of stay, and per day cost of psychiatric patients who do and do not have co-morbid medical conditions treated in 14 psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang Province in 2010 (Yuan*)

The current health reforms in China aim to greatly increase community-based services for the mentally ill. To do this it is important to understand what services these patients need. We have demonstrated that high-quality medical care for somatic conditions is an important component of treating patients with psychiatric conditions so community services for the mentally ill cannot be limited to psychiatric rehabilitation by non-medical personnel. More detailed research is needed to assess the quality and appropriateness of the non-psychiatric medical care being received by psychiatric patients but it is already clear that improved in-service training in internal medicine for mental health providers and substantial funding for non-psychiatric health care is needed to ensure that these patients receive appropriate treatments for their physical illnesses.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest regarding this paper.

Funding

Zhejiang Provincial Non-profit Applied Technology Project (number: 2010C33003).

Table 4. Multiple regression analysis of factors associated with duration of admission and per day cost of hospitalization in 7684 discharges from 14 psychiatric hospitals in Zhejiang Province, China in 2010

1. Cournos F, Mckinnon K, Sullivan G. Schizophrenia and co-morbid human immunodeficiency virus of hepatitis C virus. J Clin Psychiatry, 2005, 66(6):27-33.

2. Geng ZQ, Wang YS. The composition of psychiatric disorders in psychiatric inpatients. Chinese Journal of Hospital Statistics,2008, 15(9):287-289. (in Chinese)

3. Xin JC, Xu HD, Chen J, Wang ZU. Time-point survey of antipsychotics prescriptions for inpatients with mental disorders.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry, 2008, 20(2):92-95. (in Chinese)

4. Psychiatric Branch of Chinese Medical Association. Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. (CCMD-3).Jinan:Shandong Science and Technology Press, 2001:31-168. (in Chinese)

5. Zar HG. Biostatistical Analysis (4th edition). Prentice Hall: New Jersey, 1999:223-225, 563-565.

6. Sun SY. Survey of inpatients with mental disorder combined with somatic disease. Journal of Clinical Psychological Medicine,2007, 17(1):42-43. (in Chinese)

7. Hu RY, Yu M, Zhong JM, Gong WW. The changing trends of the incidences and the risk factors of chronic diseases among residents in the cities and rural areas in Zhejiang Province.Disease Surveillance, 2006, 21(9):480-483. (in Chinese)

8. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, Henderson DC, Freudenreich O, Copeland PM, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia:guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry, 2005,66(7):183-194.

9. Wan Q, Sun L, Shi SX. The count and analysis of influencing factors of inpatients’ expenses of mono-disorder of mental illness. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics, 2003, 20(1):27-29. (in Chinese)

10. Yuan Q, Yuan KC, Li QH, Xu LZ, Wang XZ, Song PP, et al.Multivariate stepwise regression analysis on factors affecting hospitalization cost for diabetes mellitus treatment. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics, 2008, 25(4):360-362. (in Chinese)

11. Lin SY, Gao ZS, Chen XZ, Luo MQ, Zheng SY. A study on the hospitalization expenses and in fluencing factors in schizophrenic inpatients. Chinese Journal of Hospital Statistics, 2009, 16(1):37-39. (in Chinese)

12. Fu Z, Zhang L. Theory and practice of case classification management. Beijing:People’s Military Medical Press, 2002:125-129. (in Chinese)

13. Chen XY, Zeng BT. The ethical value of single-disease entity expenditure-control in hospital. Medicine and Philosophy:Humanistic and Social Medicine Edition, 2008,29(1):49-50. (in Chinese)

浙江省精神病专科医院住院患者治疗费用调查

杨胜良1钱敏才1陆 炜1王春生2陈海支1费锦锋1沈鑫华1杨剑虹1

浙江省公益性技术应用研究计划项目(2010C33003)

1浙江省湖州市第三人民医院313000;2浙江省湖州师范学院医学院313000。

杨胜良,电子信箱:ysl7250@126.com

背景目前很少有关于精神疾病住院患者精神疾病和非精神疾病治疗费用的研究,而这方面的信息对规划精神卫生服务和医疗保险具有重要意义。

目的对2010年浙江省精神病专科医院住院患者的住院费用进行评估。

方法采用两阶段分层随机抽样方法从浙江省42家精神专科医院中抽出14家精神病院,再从抽出的各家医院中以月份为基本单位系统抽出2010年3个月(3、7、11月)的出院患者进行调查。编制《出院患者住院情况调查表》,收集患者的人口学特征、临床特征及多项住院费用信息。

结果共调查住院患者7 684例。患者的平均住院时间(四分位数)为30(20-52)d,平均总住院费用为10 005(6 419-14 728)元(1 539美元),平均药费为2 512(1 161-4 182)元,其中65%为非精神科药费,1 798(24.3%)例患者入院时伴有需要治疗的一种或多种躯体疾病,包括高血压、白细胞减少、糖尿病和各种感染。患者的精神疾病诊断不同,其躯体疾病合并症不同。经过排除其他混杂因素后,共病躯体疾病患者的住院费用显著增加,但住院时间未增加。对于精神分裂症患者,精神科的药费显著高于非精神科药费,但其他精神疾病患者的花费情况与之相反。

结论精神病院住院患者的费用中,躯体疾病的治疗费用占较大比例。在修订精神疾病的补偿措施、建立诊断相关的支付方案以及建立诊断特定的治疗指南时,都需要考虑到精神疾病伴发躯体疾病的高患病率和治疗费用,也需要确保精神科医生的在职培训能使他们及时了解常见躯体疾病的诊断和治疗的新进展。

精神疾病 医疗费用 合并症 调查

10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2011.06.002

1The Third People’s Hospital of Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province, Huzhou 313000, China

2Faculty of Medicine, Huzhou Teachers College, Huzhou 313000, China

* Correspondence: ysl7250@126.com

(received: 2011-07-21; accepted: 2011-11-02)

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- Mental health literacy in Changsha, China

- Eight-week follow-up of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis B, patients with hepatitis B cirrhosis and normal control subjects

- Relationship between blood levels and clinical efficacy of two different formulations of venlafaxine in female patients with depression

- 苯丙胺类兴奋剂所致精神障碍的临床诊治问题

- Biostatistics in Psychiatry (6)Estimating treatment effects in observational studies

- Management of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)—no easy solution