Optimal velocity encoding during measurement of cerebral blood flow volume using phase-contrast magnetic resonance angiography*☆

Gang Guo, Yonggui Yang, Weiqun Yang

Department of Radiology, Xiamen Second Hospital, Teaching Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Xiamen 361021, Fujian Province, China

INTRODUCTION

Accurate quantification of cerebral blood flow volume has many potential clinical applications in cerebrovascular diseases,such as measurement of the hemodynamic effect of carotid stenosis, monitoring cerebral blood flow after carotid endarterectomy, investigating vertebrobasilar insufficiency, evaluating the vasomotor response of an affected cerebral territory and idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and diagnosis of aqueductal stenosis[1-8].

It is important to select the optimal velocity encoding (VENC) for brain blood flow measurement using phase-contrast magnetic resonance angiography (PCMRA),as well as the intracranial venous outflow to arterial inflow ratio, an important pathophysiological index[1-2]. This study aimed to determine the optimal VENC for single acquisition assessment of cerebral arterial inflow and venous outflow through application of a range of VENCs in normal volunteers.

RESULTS

Quantitative analysis of subjects

A total of 10 healthy volunteers who were staff from the Department of Radiology,Xiamen Second Hospital in China and their family members, were included in the final analysis.

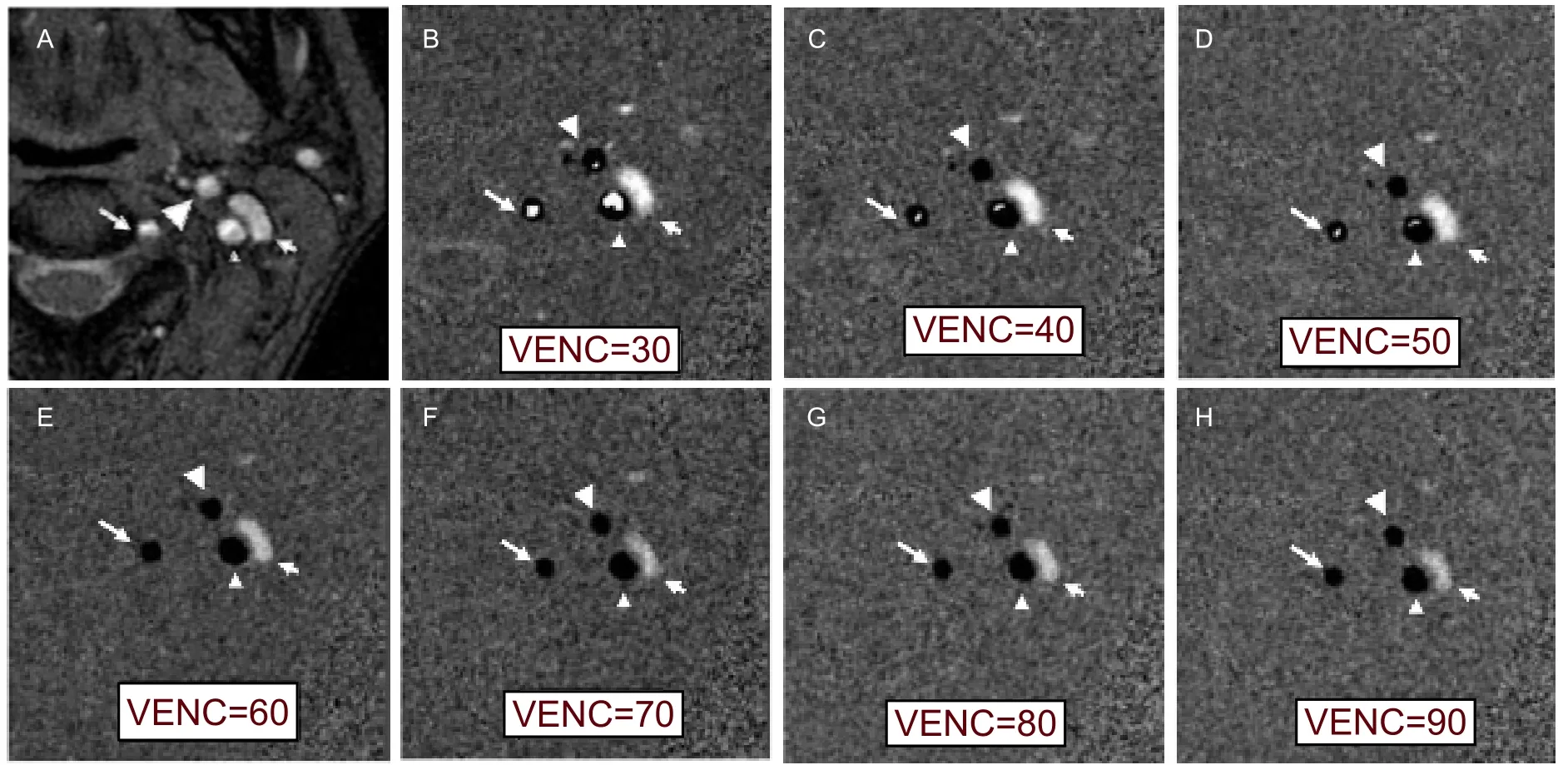

PCMRA image of subjects when velocity encoding was between 30 and 90 cm/s

In all subjects, the bilateral internal carotid artery (ICA), vertebral artery, and jugular vein were successfully displayed and measured by the PCMRA technique.

The magnitude and phase images at the C2level for different VENCs in one volunteer are shown in Figure 1. All subjects showed aliasing on phase images when VENC was 30 cm/s. No aliasing was observed with a VENC of 60 cm/s or greater.

Blood flow volume of subjects when velocity encoding was between 30 and 90 cm/s

The maximal peak velocity of the ICA was 60 cm/s. The mean flow velocities of the left and right ICA were 30.2 cm/s and 28.8 cm/s, respectively. The peak flow velocities of the left and right vertebral arteries were 24 cm/s and 23 cm/s,respectively. There were no significant differences in the peak flow velocity and mean flow volume between the paired arteries. The mean blood flow volumes of inflow and outflow in different VENCs are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1 Magnitude (A) and phase images (B-H) at the C2level for different velocity encodings (VENCs, cm/s), showing the internal carotid artery (small arrowhead), external carotid artery (large arrowhead), vertebral artery (long arrow), and jugular vein(short arrow). Aliasing (high signal in arteries) decreases and gradually disappears with increased VENCs. No aliasing was observed with a VENC of 60 cm/s or greater.

Table 2 Outflow measurements with different velocity encodings (VENCs) (mL/min)

PCMRA measurement of optimal VENC of cerebral blood flow

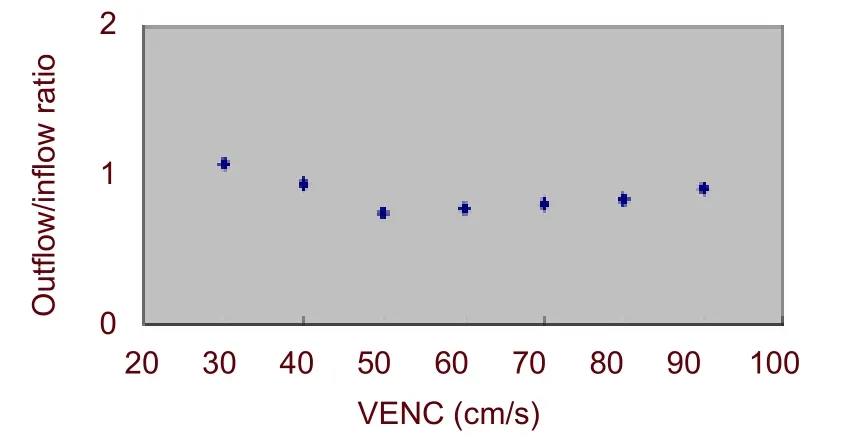

The mean inflow and outflow blood volume (mL/min)measured with PCMRA over an averaged cycle is shown in Figure 2. The ratio of outflow/inflow volume of intracranial blood for different VENCs is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2 Plot of arterial inflow and venous outflow for different velocity encodings (VENCs). Maximum arterial inflow was obtained when VENC was 60 cm/s.

Figure 3 Plot of the venous outflow to arterial inflow ratio.The outflow/inflow ratio is relatively stable with velocity encoding (VENC) between 60 and 80 cm/s.

When VENC was 30 cm/s, the arterial inflow volume and the blood flow volume of both ICAs were significantly lower than the blood flow volume obtained with other VENCs (P < 0.05). The peak flow and mean flow velocities of the ICA were also significantly lower than those obtained with other VENCs (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences when VENC was ≥ 40 cm/s (P > 0.05; Table 1, Figure 2). For the vertebral artery and jugular vein, the blood flow volume,and peak flow and mean flow velocities were not significantly different when VENC was from 30 to 90 cm/s(P > 0.05). Unexpectedly, we observed a decrease in venous outflow at a VENC of 50 cm/s (Table 2, Figure 2;detailed data not shown).

When VENCs were less than 50 cm/s or more than 90 cm/s, the ratio of outflow/inflow was equal to or more than 1. When VENCs were 60-80 cm/s, the ratio of outflow/inflow was steady at 0.78-0.83 (Figure 3), and there was no aliasing in any of the images (Figure 1).

The inflow blood volume was 655 ± 118 mL/min, and the outflow volume was 506 ± 186 mL/min.

DISCUSSION

In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that PCMRA provides reliable flow data[3,5,9-13]. However,considerable differences in total cerebral blood flow have been found in healthy volunteers using PCMRA[2,14].

These differences could be due to a lack of accuracy and reproducibility of the method[1,15]. The accuracy of PCMRA is affected by the effects of acceleration and eddy currents and by partial volume effects[4,14].

Knowledge of these issues can assist in optimizing sequence parameters to maintain error below 10%,which is an acceptable level of error for routine clinical use[10,16-17]. In general, the accuracy is improved by increasing the spatial resolution, decreasing the contrast between flowing blood and surrounding tissue and the VENC[13, 18-19].

Results of the PCMRA method show good correspondence to results of invasive techniques based on thermodilution, the ink-indicator method, and the Fick principle[20-21]. However, accurate quantification of blood flow volume in patients is difficult because of many well-documented errors inherent in the technique, and lack of evaluating standards[10,22]. A standardized protocol should be applied to minimize error with imaging parameters carefully selected to minimize the impact of the potential sources of error[23].

In the present study, multiple VENCs were used for demonstrating the variability of cerebral arterial inflow and venous outflow volumes with different VENCs. The data from this study showed that when VENC was 30 cm/s, all the subjects had aliasing in the phase images. As a result, blood flow volume was significantly reduced in the ICA. The aliasing in the ICA gradually decreased with increased VENC. Setting the VENC below the peak flow velocity in the vessel of interest always resulted in aliasing. To prevent aliasing, the VENC should be set above the maximum velocity anticipated in the vessel of interest[10]. However, the VENC should not be set too high. An increase in VENC invokes a proportional degradation of the precision[22]because of an increase in random error in velocity images[24]. In the present study, the maximum arterial inflow volume was obtained when VENC was 60 cm/s.

Arterial inflow slightly decreased with increased VENC.

In contrast, the venous outflow increased with increased VENC when VENC was ≥ 50 cm/s. The arterial inflow and venous outflow were similar with a VENC of 60 to 80 cm/s with flow volumes. Furthermore, we clearly showed that VENC less than 40 cm/s or more than 90 cm/s was not appropriate for intracranial blood flow measurement at the cervical level.

In theory, total brain arterial inflow can be assessed by summing the flows in the cervical carotid and vertebral arteries. Most of the venous outflow can be captured by the sum of the flows in both internal jugular veins. The arterial and venous flows measured by this method are not identical because a small percentage of venous outflow passes through alternate venous pathways, such as the vertebral venous system (lateral, posterior, and anterior condylar veins and the mastoid and occipital emissary veins)[8,25-27]. This method is only appropriate for reclining subjects since it is well known that the dominant venous drainage from the brain passes through the vertebral venous system in the erect position[28-29]. Validation that VENC of 60 to 80 cm/s is optimal for accurate measurement of cerebral blood flow using PCMRA can be derived from the relationship between brain blood flow and brain mass. It has been shown that mean regional cerebral blood flow is approximately 50 mL/100 g/min[30]. Brain weight predicted by selecting a VENC of 80 cm/s was 1.31 ±0.24 kg, which closely approximates the values of human brain weight (men, about 1.5 kg; women, about 1.3 kg)[30].

This study demonstrates the feasibility of measuring cerebral venous outflow and arterial inflow using a single optimally placed axial slice through C2. We determined that this ratio in normal reclining adults was approximately 0.80 through a relatively broad range of VENCs (60-80) cm/s. We believe that this method may be useful for quantitating the degree of alternate venous drainage in cerebrovascular disorders that result in sinovenous obstruction or elevated pressure. This index could provide valuable information for assessing the effectiveness of therapies used to manage these patients.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Design

Randomized, controlled, clinical trials.

坐标转换广泛采用的方法有二维转换模型[1,3]与三维转换模型[4]。其中,三维转换模型严密,但需要知道独立坐标系的中央子午线,抬高投影面高、点位大地高、地方坐标系参考椭球等信息,其应用不是很广泛;二维转换模型主要是对两坐标系进行尺度与旋转参数的线性化近似处理,方法简单,已得到广泛采用,但该方法未考虑坐标的非线性影响因素。神经网络具有自适应、自组织、自学习等智能处理能力,特别适合处理多因素影响下的非确定性信息问题,已广泛应用于地图数字化[5]、大地水准面精化[6]等多个领域。本文采用基于BP神经网络的方法进行独立坐标系向1980西安坐标系转换,削弱坐标转换中系统误差和其他异常误差的影响。

Time and setting

This experiment was performed at the Department of Radiology of Xiamen Second Hospital, China from March to May 2006.

Subjects

Ten volunteers were selected from the staff of Department of Radiology of Xiamen Second Hospital and their family members. The mean age of the subjects was 43 years (range, 21-75 years) and there were seven males and three females. All subjects provided written informed consent by our institutional research ethics board. The subjects were in good health and free of cardiovascular disease. All of them were right-handed.

Methods

PCMRA measurement of cerebral blood flow volume

Patients rested on an examination table for 10 minutes before blood flow volume measurements were conducted. Measurements were obtained on a 1.5 T MR system (Signa cv/I; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI,USA). A quadrature head coil was used to assess flow in the left and right ICAs, vertebral artery and jugular vein.

The appropriate scan level was determined on the basis of a two-dimensional time-of-fly magnetic resonance angiography (2D TOF MRA). A single 2D PC MRA slice was applied perpendicular to the ICA and the vertebral artery at C2(Figure 4). The imaging plane was carefully chosen perpendicular to the vessels of interest to minimize partial volume and oblique artifacts. Gating was performed retrospectively with a peripheral pulse unit.

Figure 4 Sagittal plane (A) and two-dimensional time-of-fly magnetic resonance angiography (2D TOF MRA) (B, C) for locating the scan slice at the C2 level. The slice was set perpendicular to the internal cerebral artery and vertebral artery on the corresponding oblique projection of 2D TOF MRA. The white parallel dashed line represents the scan plane.

The sequence parameters used in the present study included: repetition time = 40 ms; echo time = 6.6 ms;flip angle, 20°; slice thickness, 4 mm; matrix size, 256 ×256; and field of view, 140 mm × 140 mm. Forty images(20 phase images and 20 corresponding magnitude images) were obtained over each cardiac circle. For each subject, the VENC was set from 30 to 90 cm/s with an interval of 10 cm/s for a total of seven settings. Scan duration for each VENC was 3 to 4 minutes depending on heart rate.

Flow and velocity measurements were analyzed using CV Flow software on a GE Advantage Windows Workstation (4.0). For this analysis, a region of interest was manually drawn around the vessel of interest on the magnitude image at the static phase. This contour was then used for subsequent phase images. Visually, all phase images were screened for correct positioning of the region of interest. If required, the region of interest was manually adjusted. Peak flow velocity, mean flow velocity, and blood flow volumes of the bilateral ICAs,vertebral arteries, and jugular veins for each VENC were determined. All images were evaluated and analyzed by the same reader. The inflow volume of cerebral blood flow was the sum of the blood flow volumes of bilateral ICAs and vertebral arteries. The outflow volume of cerebral blood flow was the sum of the blood flow volumes of bilateral jugular veins.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 11.0 (SPSS,Chicago, IL, USA), and were expressed as mean ± SD. A paired sample t-test was used to determine the statistical significance of the differences between blood flow volume, peak flow velocity, and mean flow velocity of bilateral ICAs, the vertebral artery, and the jugular vein for different VENCs. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions:Gang Guo participated in the study concept and design, manuscript writing, and obtained funding.Yonggui Yang participated in data analysis and provided statistical expertise. Weiqun Yang participated in manuscript authorization and supervised the experiments.

Conflicts of interest:None declared.

Funding:This work was supported by the Medical Program of the Scientific & Technical Foundation in Xiamen (MRI study of chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency) in 2008, No.3502Z20084028.

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiamen Second Hospital in China.

[1]Spilt A, Box FM, van der Geest RJ, et al. Reproducibility of total cerebral blood flow measurements using phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16(1):1-5.

[2]Buijs PC, Krabbe-Hartkamp MJ, Bakker CJ, et al. Effect of age on cerebral blood flow: measurement with ungated two-dimensional phase-contrast MR angiography in 250 adults. Radiology. 1998;209(3):667-674.

[3]Taviani V, Patterson AJ, Graves MJ, et al. Accuracy and repeatability of fourier velocity encoded M-mode and two-dimensional cine phase contrast for pulse wave velocity measurement in the descending aorta. J Magn Reson Imaging.2010;31(5):1185-1194.

[4]Amano Y, Takagi R, Suzuki Y, et al. Three-dimensional velocity mapping of thoracic aorta and supra-aortic arteries in Takayasu arteritis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31(6):1481-1485.

[5]Wentland AL, Wieben O, Korosec FR, et al. Accuracy and reproducibility of phase-contrast MR imaging measurements for CSF flow. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(7):1331-1336.

[6]Stoquart-El Sankari S, Lehmann P, Gondry-Jouet C, et al.Phase-contrast MR imaging support for the diagnosis of aqueductal stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(1):209-214.

[7]Chiang WW, Takoudis CG, Lee SH, et al. Relationship between ventricular morphology and aqueductal cerebrospinal fluid flow in healthy and communicating hydrocephalus. Invest Radiol. 2009;44(4):192-199.

[8]Nedelmann M, Kaps M, Mueller-Forell W. Venous obstruction and jugular valve insufficiency in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol. 2009;256(6):964-969.

[9]Hansen KL, Udesen J, Oddershede N, et al. In vivo comparison of three ultrasound vector velocity techniques to MR phase contrast angiography. Ultrasonics. 2009;49(8):659-667.

[10]Lotz J, Meier C, Leppert A, et al. Cardiovascular flow measurement with phase-contrast MR imaging: basic facts and implementation. Radiographics. 2002;22(3):651-671.

[11]Hsiao A, Alley MT, Massaband P, et al. Improved cardiovascular flow quantification with time-resolved volumetric phase-contrast MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41(6):711-720.

[12]Dyverfeldt P, Sigfridsson A, Knutsson H, et al. A novel MRI framework for the quantification of any moment of arbitrary velocity distributions. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(3):725-731.

[13]Van Es AC, Van der Grond J, ten Dam VH, et al. Associations between total cerebral blood flow and age related changes of the brain. PLoS ONE 2010;5(3):e9825.

[14]Zhao M, Charbel FT, Alperin N, et al. Improved phase-contrast flow quantification by three-dimensional vessel localization. Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;18(6):697-706.

[15]Kang CK, Kim SH, Lee H, et al. Functional MR angiography using phase contrast imaging technique at 3T MRI. Neuroimage. 2010;50(3):1036-1043.

[16]Hollnagel DI, Summers PE, Poulikakos D, et al. Comparative velocity investigations in cerebral arteries and aneurysms: 3D phase-contrast MR angiography, laser Doppler velocimetry and computational fluid dynamics. NMR Biomed. 2009;22(8):795-808.

[17]Lehmpfuhl MC, Hess A, Gaudnek MA, et al. Fluid dynamic simulation of rat brain vessels, geometrically reconstructed from MR-angiography and validated using phase contrast angiography.Phys Med. 2011;27(3):169-176.

[18]Hollnagel DI, Summers PE, Kollias SS, et al. Laser Doppler velocimetry (LDV) and 3D phase-contrast magnetic resonance angiography (PC-MRA) velocity measurements: validation in an anatomically accurate cerebral artery aneurysm model with steady flow. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(6):1493-1505.

[19]Chang W, Landgraf B, Johnson KM, et al. Velocity measurements in the middle cerebral arteries of healthy volunteers using 3D radial phase-contrast HYPRFlow: comparison with transcranial Doppler sonography and 2D phase-contrast MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(1):54-59.

[20]Markl M, Harloff A, Bley TA, et al. Time-resolved 3D MR velocity mapping at 3T: improved navigator-gated assessment of vascular anatomy and blood flow. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(4):824-831.

[21]Hoeper MM, Tongers J, Leppert A, et al. Evaluation of right ventricular performance with a right ventricular ejection fraction thermodilution catheter and MRI in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2001;120(2):502-507.

[22]Bakker CJ, Hoogeveen RM, Viergever MA. Construction of a protocol for measuring blood flow by two-dimensional phase-contrast MRA. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9(1):119-127.

[23]de Boorder MJ, Hendrikse J, van der Grond J. Phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging measurements of cerebral autoregulation with a breath-hold challenge: a feasibility study.Stroke. 2004;35(6):1350-1354.

[24]Ho SS, Metreweli C. Preferred technique for blood flow volume measurement in cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 2000;31(6):1342-1345.

[25]Kirchhof K, Welzel T, Jansen O, et al. More reliable noninvasive visualization of the cerebral veins and dural sinuses: comparison of three MR angiographic techniques. Radiology. 2002;224(3):804-810.

[26]Passat N, Ronse C, Baruthio J, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography: from anatomical knowledge modeling to vessel segmentation. Med Image Anal. 2006;10(2):259-274.

[27]Anzalone N. Contrast-enhanced MRA of intracranial vessels. Eur Radiol. 2005;15 Suppl 5:E3-10.

[28]San Millán Ruíz D, Gailloud P, Rüfenacht DA, et al. The craniocervical venous system in relation to cerebral venous drainage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(9):1500-1508.

[29]Fisher M. The pathophysiology of ischaemic stroke. In: Fisher M,eds. Clinical Atlas of Cerebrovascular Disorders. London:Mosby-Year Book. 1994.

[30]Orrison WW, Lewine JD, Sanders JA, et al. Functional Brain Imaging. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book. 1995.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- NIH funding for disease categories related to neurodegenerative diseases

- A case of thalamic hemorrhage-induced diaschisis☆

- Occlusion of the middle cerebral artery Guidance by screen imaging using an EDA-H portable medium-soft electronic endoscope☆

- Propofol regulates Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ balance in the spinal cord after ischemia/reperfusion injury***★

- Using Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry to analyze differentially expressed brain polypeptides in scrapie strain 22L-infected BALB/c mice***☆

- Evidence-based treatment for acute spinal cord injury☆