Propofol regulates Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ balance in the spinal cord after ischemia/reperfusion injury***★

Shuzhou Yin, Qijing Yu, Ji Hu, Jie Yang, Juan Chen

1Department of Anesthesiology, Suzhou Kowloon Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Suzhou 215021, Jiangsu Province, China

2Department of Anesthesiology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430060, Hubei Province, China

3Department of Anesthesiology, Liyuan Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan 430077,Hubei Province, China

INTRODUCTION

Various methods have been developed to protect the spinal cord from injury and prevent the development of paraplegia during aortic surgery[1-2]. We have previously reported that co-application of the commonly used anesthetic, propofol,during ischemic pre- and post-conditioning prevents neurological injury in a rabbit model of spinal cord ischemia[3]. We also reported that four cycles of ischemic preconditioning (5 minutes of ischemia followed by 5 minutes of reperfusion)effectively prevents spinal cord injury, in association with a correction of the imbalance in Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+within the ischemic region[4]. However, it is not clear whether propofol can influence the balance of metal ions in the ischemic region during spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. In the present study, we used an I/R injury model induced via aortic occlusion in rabbits to test the effects of propofol in maintaining the balance of ions in I/R affected spinal cord tissues.

RESULTS

Quantitative analysis and grouping of experimental animals

A total of 24 rabbits were randomly assigned in even numbers into three groups: sham surgery, I/R, and I/R + propofol treatment. All rabbits survived and were included in the analysis of post-surgical neurological functions.

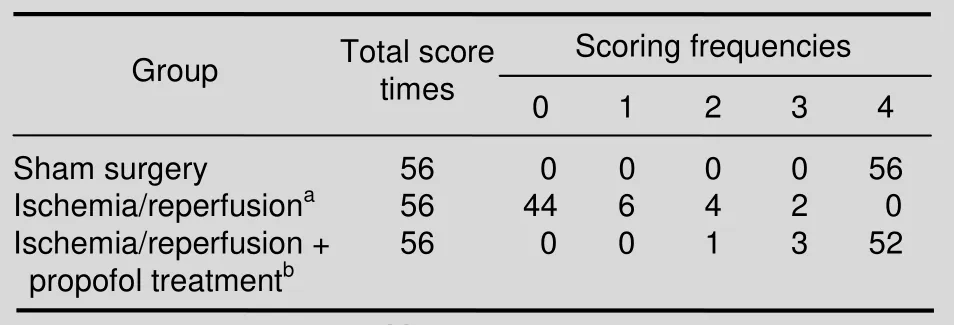

Comparison of hindlimb neurological function among three groups

After surgery, changes in neurological function were scored in all animals, as shown in Table 1. A high score indicates normal functioning. The scores of animals in the I/R group were significantly lower than those in the sham surgery group (P <0.01), and the I/R + propofol treatment group (P < 0.01). Neurological function scores were not different between the I/R + propofol treatment and the sham surgery groups (P > 0.05). Paraplegia was found in all animals in the I/R group (8/8),but in none of the animals in the sham surgery group or the I/R + propofol treatment group.

Table 1 Comparisons of neurological function scores of hind limbs

Changes in Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ concentrations in serum

Blood sampling time points were as follows: 40 minutes before ischemia (C-40), immediately after reperfusion (R0),60 minutes of reperfusion (R60) and 7 days after reperfusion (R7d). The concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+in the serum were determined by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

Serum Ca2+concentrations in the I/R group gradually increased after ischemia, and were significantly higher after reperfusion compared with pre-reperfusion.

Additionally, these concentrations were higher than the corresponding values in the sham surgery and the I/R +propofol treatment groups (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01,respectively). There were no significant differences in serum Ca2+concentrations between the different time points in the I/R + propofol treatment group (Table 2).

Table 2 Changes in serum Ca2+concentrations among three groups (mg/L)

After reperfusion, serum Mg2+concentrations in the I/R group were significantly lower than those of the pre-ischemia values in the same group, as well as those in the sham surgery group (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01,respectively). Serum Mg2+concentrations did not change significantly in the I/R + propofol treatment group during I/R (Table 3).

Table 3 Changes in serum Mg2+ concentrations among three groups (mg/L)

Serum Cu2+concentrations in the I/R group were higher after reperfusion compared with pre-ischemia values in the I/R and the sham surgery groups (P < 0.05 and P <0.01, respectively). Also, serum Cu2+concentrations at R7dwere significantly higher in the I/R group in comparison to the I/R + propofol treatment group (P <0.05). There were no significant changes in serum Cu2+concentrations over time in the I/R + propofol treatment group (Table 4).

Table 4 Changes in serum Cu2+ concentrations among three groups (mg/L)

Compared with pre-ischemia values in the I/R and sham surgery groups, serum concentrations of Zn2+in the I/R group were significantly lower after reperfusion (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively). Serum Zn2+concentrations did not vary significantly at each time point in the I/R +propofol treatment group, but the R7dvalue was significantly higher than the corresponding value in the I/R group (P < 0.01; Table 5).

Table 5 Changes in serum Zn2+concentrations among three groups (mg/L)

Changes in Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ concentrations in spinal cord homogenates

After 7 days of reperfusion, animals were sacrificed. The concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+in the spinal cord homogenates were determined by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

As shown in Table 6, the concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+,Cu2+and Zn2+in spinal cord tissues were not significantly different between the sham surgery and the I/R +propofol treatment groups (P > 0.05). However, the concentrations of Ca2+and Cu2+in the I/R group were significantly higher than those in the sham surgery and I/R + propofol treatment groups (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01,respectively). Conversely, the concentrations of Mg2+and Zn2+in the I/R group were significantly lower than those in the sham surgery or the I/R + propofol treatment groups (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively).

Table 6 Changes in Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ concentrations in spinal cord homogenates (mg/L)

DISCUSSION

In our animal model, spinal cord I/R injury was induced via 40 minutes of infrarenal aortic cross-clamping (1 cm below the left artery) followed by 7 days of reperfusion.

Although there may have been collateral blood flow, the occlusion was great enough to induce spinal cord ischemia.However, we found that animals treated with two intravenous infusions of propofol (one delivered at 10 minutes before aortic clamping [pre-I/R]and one at the onset of reperfusion) reversed the I/R-induced damage. Our results indicated that propofol treatment reversed I/R damage in all of the parameters analyzed,including neurological functioning of the hind limbs, blood serum metal ion concentrations, and spinal cord homogenates. Despite the considerable neuroprotective effects of propofol observed, the underlying mechanisms are still unclear.

Changes in multi-ion channels or cell membrane permeability are key factors in producing ischemic tolerance via ischemic preconditioning[6]. Additionally, the redistribution of extracellular and intracellular metal ions correlate with cellular damage during I/R[7]. Prior to this study, little was known about the effects of propofol on metal ions during spinal cord I/R injury. The present study revealed that propofol can maintain concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+at normal levels following 40 minutes of ischemia and 7 days of reperfusion.

Conversely, the animals in the I/R group without the treatment retained significantly higher levels of Ca2+and Cu2+, and significantly lower levels of Mg2+and Zn2+compared with control animals.

Cations play important roles in the development of I/R injury. Intracellular Ca2+overload is one of the key factors leading to cell death during I/R[8-9]. As an antagonist of Ca2+, Mg2+can inhibit Ca2+influx, thereby resulting in the recovery of neuron function after injury[10-11]. Increased Cu2+contents accelerate lipid oxidation, and consequently increase free radical production, resulting in the development or worsening of tissue injuries[12]. As one of the metal elements of superoxide dismutase, Zn2+can block Ca2+channels[13]. Zinc deficiency not only induces oxidative cell membrane damage, but also alters the functioning of membrane ion channels and carriers,as well as carriage proteins[14]. Increased permeability of cell membranes and the opening of ion channels results in a large influx of Ca2+, and an outflow of Mg2+, which induces a partial loss of ion balance and an increase in tissue injury[4]. On the other hand, spinal cord injury can result in the imbalance of metal ions. It has been reported that spinal cord injury can damage cell membranes, and decrease ion pump activity and energy barriers, thereby leading to a loss in a large number of Mg2+via renal excretion[15]. Spinal cord I/R injury induces a stress response, and consequently releases glucocorticoid and adrenocorticotropic hormones to speed up tissue repair. In turn, these hormones consume a large amount of zinc, and lead to a decrease in serum Zn2+concentration[16]. During repair of spinal cord injury,enhanced synthesis of enzymes can lead to an increase in Cu2+within spinal tissue[12].

The precise mechanism by which a co-application of propofol during pre- and post-conditioning leads to changes in Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+concentrations in both serum and spinal cord tissues of rabbits requires further study. However, recent studies suggested that the functional changes of K-ATP ion channels may be the central part of ischemic tolerance caused by ischemic preconditioning[17]. Whether a co-application of propofol during pre- and post-conditioning regulates the balance of Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+in I/R affected spinal cords by activating K-ATP channels is also worthy of further investigation.

Propofol treatment may also induce tissue release of other reagents that can affect cell membrane permeability and function. Further research is needed to test these possibilities.

In summary, propofol treatment reverses the imbalance of metal ions induced by spinal cord injury. This finding may help to develop new drugs for maintaining the ion balance in I/R affected spinal cord tissues, as well as more simple and effective methods for preventing spinal cord injury during aortic clamping operations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

A randomized controlled animal experiment.

Time and setting

The experiment was conducted at the Anesthesiology Laboratory of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University,China between May 2010 and June 2011.

Materials

A total of 24 white adult Japanese rabbits of either gender, aged 3 months and weighing 2.2-2.7 kg, were supplied by the Experimental Animal Institute of Wuhan University [certification No. SYXK (E) 20080003]. All protocols were in strict accordance with the Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,formulated by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China[18].

Methods

Surgical procedure

Rabbits were intravenously infused with 3% sodium pentobarbital (15 mg/kg in 5 mL 0.9% saline),endotracheally intubated, and finally connected to a small-animal respirator (Model DH140B; Zhejiang Medical Instrument Factory, Zhejiang, China).

Respiration was set at 30 breaths/minute, with a 1.5: 1 inspiration to expiration ratio. The level of PaCO2was maintained at 4.67-6.00 kPa. Ringer’s solution was infused at 10 mL/kg per hour through an ear vein, and an additional dose of 3% sodium pentobarbital (0.5 mL/kg)and rocuronium (0.5 mg/kg) were administered at regular intervals. Following intravenous heparin (3 mg/kg)administration, the right femoral artery was exposed, and a catheter with an arterial line connected to a pressure/heart transducer (LIFESCOPEE9; Japan Optical Co., Ltd., JO BLDG, Japan) was inserted for continuous monitoring of arterial pressure. Arterial pressures, both distal and proximal to the cross clamp,were measured, and mean arterial pressure was calculated. With the aid of a heating pad, the rectal body temperature was maintained at approximately 38 °C.

Aortic occlusion

To initiate I/R injury by aortic occlusion[5], the skin was incised along the lateral vertical side of the erector spinae muscle below the left costal verge. The abdominal aorta was exposed outside the peritoneum,and a silicone plastic tube of a small diameter was placed around the abdominal aorta at the distal side,1 cm below the left artery. Aortic occlusion was induced by pulling and clamping the surrounding plastic tubing until the distal mean arterial pressure reached 0 mm Hg(1 mm Hg = 0.133 kPa).

I/R injury and propofol treatment

Spinal cord ischemia was induced by a 40-minute infra-renal aortic cross-clamp in the I/R and I/R +propofol treatment groups. Immediately following occlusion, distal blood pressure decreased and the pulse disappeared. Reperfusion was initiated by removing the occlusion, which was continued for 7 days. During study optimization, a range of propofol concentrations were tested, including 20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 mg/kg. Based on the best benefits and the least adverse effects, the optimal dose for propofol was determined to be 30 mg/kg,and was used in this study (supplementary Table 1 online). Propofol (30 mg/kg, AstraZeneca Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China; lot No.

J20030039) in 30 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride was intravenously infused at a speed of 3 mL/min on two occasions in the I/R + propofol treatment group: 10 minutes before aortic clamping (pre-I/R) and at the onset of reperfusion. Animals in the I/R group underwent standard aortic occlusion and intravenous injection of the same volume of 0.9% sodium chloride without propofol under identical conditions. Sham operated animals were subjected to similar dissections, with the exception of aortic occlusion, and underwent intravenous injection of a similar volume of 0.9% sodium chloride without propofol and under identical conditions. An antibiotic(400 000 U penicillin) was administered intramuscularly immediately after the operating procedures. Wounds were then sutured and the rabbits were returned to their cages for observation.

Hindlimb motor function

During reperfusion, rabbits were assessed daily for their hindlimb motor functions by an observer, who was blinded to the experimental conditions. Each animal was evaluated each day for 7 days. Each group consisted of eight rabbits. Therefore, the motor function was assessed 56 times for each group. The modified Tarlov criteria[5]were used to score the observed neurological functions,using the following scores: 0 = paraplegia with no lowerextremity motor function; score 1 = poor lower-extremity motor function (flicker of movement or weak antigravity movement only); score 2 = some lower-extremity motor function with good antigravity strength, but an inability to draw legs under body and/or hip; score 3 = the ability to draw legs under body and hip, but with difficulty; and score 4 = normal motor function as seen in healthy animals.

Measurement of metal ion concentrations in blood serum and spinal cord homogenates

In each group, blood was drawn from the left femoral artery, and the serum was used to measure concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+. The blood sampling time points in all groups were, as follows: C-40,R0, R60, and R7d. At each time point, 3 mL blood was collected, allowed to coagulate for 30 minutes, and then centrifuged for 20 minutes (4 000 r/min). Serum was placed in a glass tube washed with deionized water, and preserved in deep hypothermia (-70°C). The concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+in the serum were determined via flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry (L-type spectrAA-40 atomic absorption spectrum apparatus, hollow cathode light,Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The wavelength used to determine Ca2+was 422.7 nm, Mg2+was 285.2 nm,Cu2+was 324.8 nm, and Zn2+was 213.9 nm.

Once the animals were sacrificed, approximately 1 cm of spinal cord tissue from the injured regions (L3-5) was collected and washed with triply distilled water to remove spinal dura mater and remnants of blood. Tissues were dried, weighed, and homogenized in triply distilled water.

After centrifugation, supernatants were collected and stored at -70°C for further analyses. Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+concentrations in spinal cord homogenates were determined via flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0(SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) software. The differences in concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, Cu2+and Zn2+among groups were analyzed by analysis of variance, followed by post-hoc test. Differences in neurological scores among groups were analyzed via nonparametric methods (Kruskal-Wallis test and Nemenyi test). Data were expressed as mean ± SD and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions:Shuzhou Yin, Qijing Yu and Ji Hu collected and integrated the data, proposed and designed the study, and were responsible for manuscript writing and authorization, and all contributed equally to this article and were co-first authors. Shuzhou Yin, Qijing Yu, and Ji Hu obtained funding. Jie Yang and Juan Chen were responsible for data analysis and statistical management.

Conflicts of interest:None declared.

Funding:This study was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, No. BK2009139; the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, No.2009CDB130; and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (HUST), No. M2009049.

Ethical approval:The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wuhan University, China.

Supplementary information:Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, by visiting www.nrronline.org, and entering Vol. 6, No. 23, 2011 after selecting the “NRR Current Issue” button on the page.

[1]Kahn RA, Stone ME, Moskowitz DM. Anesthetic consideration for descending thoracic aortic aneurysm repair. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;11(3):205-223.

[2]Hsieh YC, Cheng H, Chan KH, et al. Protective effect of intrathecal ketorolac in spinal cord ischemia in rats: a microdialysis study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51(4):410-414.

[3]Yu QJ, Hu J, Yang J, et al. Protective effect of propofol preconditioning and postconditioning against ischemic spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2011;6(12):951-955.

[4]Yu QJ, Wang YL, Zhou QS, et al. Effect of repetitive ischemic preconditioning on spinal cord ischemia in a rabbit model. Life Sci.2006;79(15):1479-1483.

[5]Naslund TC, Hollier LH, Money SR, et al. Protecting the ischemic spinal cord during aortic clamping. The influence of anesthetics and hypothermia. Ann Surg. 1992;215(5):409-416.

[6]Kouchi I, Murakami T, Nawada R, et al. KATP channels are common mediators of ischemic and calcium preconditioning in rabbits. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(4 Pt 2):H1106-1112.

[7]Shen C, Jiang S, Dong Y. Changes of trace element in the acute spinal cord injury. Zhongguo Zhongyi Gushangke Zazhi. 2001;9:14-16.

[8]Knott TK, Marrero HG, Fenton RA, et al. Endogenous adenosine inhibits CNS terminal Ca(2+) currents and exocytosis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210(2):309-314.

[9]Momose-Sato Y, Kinoshita M, Sato K. GABA-induced intracellular Ca2+elevation in the embryonic chick brainstem slice. Neurosci Lett. 2007;411(1):42-46.

[10]Muto O, Ando H, Ono T, et al. Reduction of oxaliplatin-related neurotoxicity by calcium and magnesium infusions. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2007;34(4):579-581.

[11]Ditor DS, John SM, Roy J, et al. Effects of polyethylene glycol and magnesium sulfate administration on clinically relevant neurological outcomes after spinal cord injury in the rat. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(7):1458-1467.

[12]Tokuda E, Ono S, Ishige K, et al. Metallothionein proteins expression, copper and zinc concentrations, and lipid peroxidation level in a rodent model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Toxicology. 2007;229(1-2):33-41.

[13]Yu RA, Xia T, Wang AG, et al. Effects of selenium and zinc on renal oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by fluoride in rats.Biomed Environ Sci. 2006;19(6):439-444.

[14]Classen HG, Gröber U, Löw D, et al. Zinc deficiency. Symptoms,causes, diagnosis and therapy. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2011;34(3):87-95.

[15]Ozdemir M, Cengiz SL, Gürbilek M, et al. Effects of magnesium sulfate on spinal cord tissue lactate and malondialdehyde levels after spinal cord trauma. Magnes Res. 2005;18(3):170-174.

[16]Kalkan E, Ciçek O, Unlü A, et al. The effects of prophylactic zinc and melatonin application on experimental spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury in rabbits: experimental study. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(11):722-730.

[17]Roseborough G, Gao D, Chen L, et al. The mitochondrial K-ATP channel opener, diazoxide, prevents ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rabbit spinal cord. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(5):1443-1451.

[18]The Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 2006-09-30.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- NIH funding for disease categories related to neurodegenerative diseases

- A case of thalamic hemorrhage-induced diaschisis☆

- Occlusion of the middle cerebral artery Guidance by screen imaging using an EDA-H portable medium-soft electronic endoscope☆

- Using Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry to analyze differentially expressed brain polypeptides in scrapie strain 22L-infected BALB/c mice***☆

- Optimal velocity encoding during measurement of cerebral blood flow volume using phase-contrast magnetic resonance angiography*☆

- Evidence-based treatment for acute spinal cord injury☆