AMF 和PGPR 单独或“跨界”互作促进植物耐盐性的研究进展

摘要: 盐碱地改良和利用对拓展我国后备耕地资源及保障国家粮食安全具有重要意义。根际微生物作为植物的“第二基因组”,在提高作物抗盐碱胁迫能力,促进作物“以种适地”方面具有巨大潜力。其中,丛枝菌根真菌(arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi,AMF) 和植物根际促生细菌(plant growth promoting rhizobacteria,PGPR) 均为重要的根际有益微生物,能显著提高植物耐盐性。本文分别总结了AMF 和PGPR 提高植物抗盐能力的相关研究进展,并进一步梳理了两者协同提高植物耐盐的机制,包括提高养分效率、调节激素内稳态、提高植物诱导抗性以及调控转录因子表达等,最后提出了基于两者跨界组合的改良方向。旨在充分理解盐胁迫条件下微生物耐盐促生的作用机制,为充分挖掘微生物资源潜力和发展生物技术治理盐碱地提供重要的科学支撑。

关键词: 盐化土壤; 丛枝菌根真菌; 植物根际促生细菌; 植物耐盐性

土壤盐碱化是指土壤中盐分离子在随水分蒸发过程中,于土壤表层形成积盐层,影响植物正常生长的现象[1]。盐碱地遍布全球100 多个国家,面积高达1×109 hm2[2]。在我国,盐碱地总面积高达3690 万hm2,其中盐碱耕地760 万hm2。据估计,土壤的盐碱胁迫将威胁到全球50% 以上的耕地,严重影响粮食安全和生态系统健康,因此盐碱地改良成为当前耕地产能提升的一个重要内容[3]。长期以来,盐碱地改良主要依赖水利工程、化学改良剂和农艺措施等传统方法,但在实际应用中常常受到水资源匮乏、高投入成本等因素的制约。根际微生物组作为植物的“第二基因组”,在促进植物营养生长,维持植物健康方面发挥重要作用[4−5]。在加强田间管理和改良土壤的基础上,结合现代生物学技术,强化“植物−土壤−微生物”互作,是新时期“以种适地”和“以地适种”相结合的一个重要突破方向。

关于微生物响应、适应盐碱生境及其对植物的促生机制的研究,正成为近年来微生物领域的研究热点。作为两类重要的根际有益微生物,丛枝菌根真菌(arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, AMF) 和植物根际促生细菌(plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, PGPR)在协同提高植物抗盐性上存在巨大的潜力。AMF 可以与陆地上约70%~80% 高等植物建立互惠共生关系,对植物的养分吸收和抗逆性具有显著的提升作用[6]。PGPR 是指分布于植物根际微域内可以促进植物生长的有益微生物类群,参与根际多种关键物质的循环转化过程[7]。植物主要通过根系分泌物来招募和塑造特异性根际微生物组[8]。与植物类似,AMF可以分泌有机酸、氨基酸和糖类等物质,在菌丝际招募和塑造核心微生物组,两者互作可显著提高其对养分的利用效率并增强植物的抗逆性[ 9 ]。然而,目前对AMF、PGPR 及两者互作提高植物耐盐能力的机制仍不清楚。随着基因组学、基因编辑等技术的快速发展,为深入研究植物−真菌−细菌三者跨界合作提供了可能性。本文总结了国内外关于AMF 和PGPR 单独及其互作提高植物耐盐能力的研究进展,以期为理解植物−AMF−PGPR 联合抗盐的机制,充分挖掘微生物资源,为绿色、高效地改良盐碱土壤提供重要理论支撑。

1 植物对盐胁迫的响应

盐胁迫对植物的影响具有多重性,Munns 等[10]提出,盐胁迫下植物存在两个过程,即起始阶段的快速渗透胁迫和后期叶片中盐离子过量积累引起的离子胁迫阶段。盐胁迫还会导致一系列的次生效应,其中主要是氧化胁迫。盐胁迫引起植物细胞内生物分子的物理或化学变化,从而引发细胞应激反应并启动一系列响应机制,主要包括渗透调节机制、离子平衡机制和抗氧化机制3 个方面[11−12]。在许多情况下,这些调控途径之间相互关联形成了复杂的调控网络。

1.1 渗透调节

随着土壤盐分的升高,土壤溶液的水势低于植物根细胞的水势,植物体内的水分子排到细胞外进而导致植物生理性干旱,形成渗透胁迫[13−14]。植物细胞会通过多种方式降低细胞渗透势,从而保持胞内外渗透压平衡,维持植物正常生理代谢[15]。植物体内的渗透调节过程主要分为两类:一类是在土壤中吸收并积累无机盐离子(如K+和Ca2+),从而快速恢复细胞膨压;另一类是植物通过自身合成有机物质调节渗透压,如合成多元醇类、甜菜碱、可溶性糖和脯氨酸等,降低细胞渗透势[16]。

1.2 离子平衡

在盐碱胁迫下,土壤中高浓度的Na+进入植物细胞并在细胞中积累,细胞中Na+的外排和木质部中Na+的回收是植物耐盐的重要途径,该过程通过高亲和力钾转运蛋白和Na+/H+逆向转运蛋白的调控来实现。植物激活高亲和力的K+转运体(HKT) 调控木质部对Na+再吸收,降低Na+的毒害。例如由拟南芥中AtHKT1、水稻中OsHKT1;4 和OsHKT1;5 以及高粱中GmHKT1;1 编码的HKT1 蛋白,增强根部木质部对Na+的回收[17]。当植物遭受盐碱胁迫后Ca2+会通过质膜和细胞器膜流入细胞质, 导致细胞质中的Ca2 +峰,Ca2 +信号依赖的盐超敏感途径(salt overlysensitive, SOS) 则在盐离子转运过程中发挥关键作用,磷脂酸与SOS2 的Lys57 残基结合后,促进其质膜定位,进而激活Na+/H+反转运蛋白SOS1,植物将过量的Na+排除到细胞外和将其区域化隔离在液泡中两种方式来缓解植物盐胁迫[18]。此外,植物还能通过促进K+吸收和液泡对Cl−的区隔化来维持细胞内离子稳态[19−23]。

1.3 抗氧化机制

植物体内活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)的积累会导致细胞膜脂质过氧化、DNA 损伤、蛋白质变形、碳水化合物氧化、色素分解和酶活性受损等,并产生有毒物质丙二醛(MDA),导致植物死亡[24]。植物体内存在两类抗氧化防御系统:一是酶促抗氧化系统,主要包括在ROS 加工中起作用的酶,如超氧化物歧化酶(SOD)、过氧化物酶(POD)、过氧化氢酶(CAT) 等。研究表明,当胁迫强度超过植物的承受能力时,这些酶的活性下降,呈先升后降的趋势[25]。二是非酶促抗氧化系统,主要包括还原型谷胱甘肽(GsH)、抗坏血酸(ASA)、氧化型谷胱甘肽(GSSG) 和类胡萝卜素等,两个系统通过清除细胞中过度积累的ROS 来维持ROS 稳态[26−27]。此外,植物还可以通过抑制miRNA ZmmiR169q 的积累,增强抗氧化酶基因ZmPER1 的表达,从而消除过量ROS[28]。

2 AMF 或PGPR 单独作用缓解盐胁迫的机制

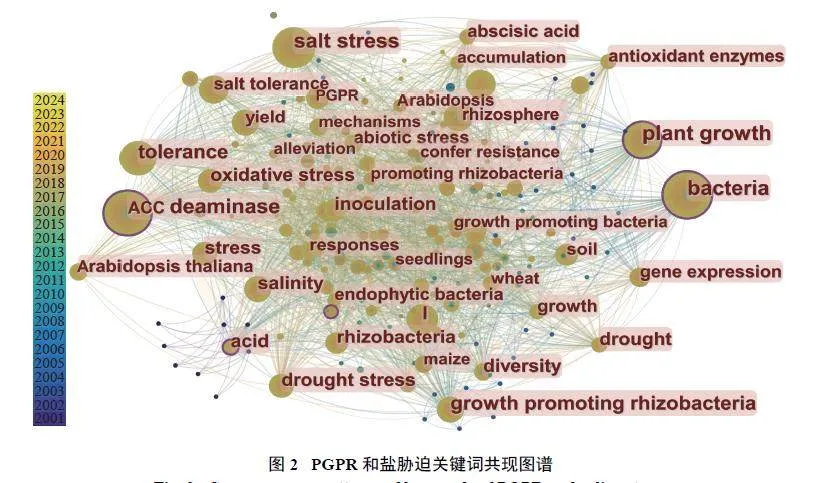

基于可视化应用软件CiteSpace,选取Web ofScience (WOS) 核心合集数据库,AMF 抗盐胁迫检索条件为主题=“AMF” and “saline” or “AMF” and“salt”,PGPR 抗盐胁迫检索条件为主题=“PGPR”and “saline” or “PGPR” and “salt”,文献类型均选择“Article”和“Review”,分别检索出该研究领域发表的文献635 篇和872 篇,进行了关键词突现性分析(图1 和图2)。可以看出,AMF 和PGPR 均影响植物耐盐性。AMF 主要通过调节植物激素,改善植物对水分和养分的利用效率,以及植物光合速率,调节离子平衡和产生抗氧化剂等发挥作用。PGPR 的相关研究则较多集中在ACC 脱氨酶、定殖过程和对植物的促生作用等方面[29]。

2.1 提高养分和水分利用效率

作为有益微生物,AMF 和PGPR 在促进土壤养分循环和植物养分吸收方面均发挥着重要作用。在盐胁迫下,两者在促进养分吸收的机制上有所区别。PGPR 主要通过直接作用,例如通过分泌有机酸、胞外磷酸酶、产生铁载体等促进土壤养分活化。例如,溶磷菌Y2R2 可以直接分泌酸性磷酸酶将难溶性无机磷化物活化为有效磷[30]。Bacillus aquimaris 和Azospirillum brasilense 能够增加生物固氮酶活性,加速氮素活化过程[31−32]。AMF 则通过菌丝的直接作用以及菌丝−菌丝际微生物的互作两种方式促进植物对养分的利用。一方面,AMF 庞大的菌丝网络扩大了根系与土壤的接触面积,提高了对磷(氮) 的吸收效率[33];另一方面,AMF 根外菌丝分泌物释放到菌丝际微域土壤,在菌丝际招募解磷菌以及氮循环相关细菌,促进了植物对养分的吸收[34−35]。

在水分吸收利用方面,AMF 和PGPR 均可通过调节植物的水通道蛋白基因的表达来促进植物吸收水分[36−37]。如贺忠群等[38]通过荧光定量研究表明,盐胁迫下接种AMF 的番茄(Solanum lycopersicum) 根系中水通道蛋白LeAQP2 基因表达显著上调。Azospirillumbrasilens、Bacillus megaterium 等PGPR 能够激活水通道蛋白相关基因(如PIP2、ZmPIP1-1 和HvPIP2-1) 表达来帮助植物在盐胁迫下吸收水分等[39]。Kakouridis等[40]通过18O 同位素标记试验发现,AMF 可以作为根系沿着土壤−植物−空气连续体水分运动的延伸,植物蒸腾作用驱动水分通过菌丝的胞质外途径输送到植物体内。

2.2 调节植物内源激素的水平

植物激素的变化是植物适应逆境胁迫的主要反应。植物受到盐胁迫时,PGPR 和AMF 显著影响植物激素水平。AMF 和PGPR 在机制上存在一些异同点,两者均可以诱导植物体内脱落酸(ABA)、赤霉素(GA)、吲哚乙酸(IAA) 和细胞分裂素(CTK) 等植物内源激素的合成[41−43]。但AMF 与PGPR 诱导植物激素水平上升并促进植物生长的途径存在一定差异。例如,有研究发现,AMF 可以调控水杨酸、茉莉酸、游离多胺类物质(如腐胺、亚精胺和精胺) 和独脚金内酯的含量,进而维持植物细胞膜稳定性[ 4 4 − 4 6 ]。PGPR 可以通过释放挥发性有机化合物(VOCs) 介导并维持盐胁迫条件下植物生长的稳态[47−48]。盐胁迫致使植物产生大量的乙烯,对植物生长有抑制作用,一些耐盐的PGPR 含有acdS 基因,能够编码1-氨基环丙烷-1-羧酸脱氢酶(aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase,ACCD),ACCD 将乙烯的前体ACC 水解成碱和α-酮丁酸盐作为氮源,从而降低乙烯的过量积累[49−51]。近80% 的固氮菌(Azotobacter)和荧光假单胞菌(Pseudomonas fluorescens) 及近20% 的芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus) 能分泌IAA,在盐胁迫下接种这些促生菌不仅能够直接促进生长,也能激发ACCD 活性,诱导植物抵抗盐胁迫损伤[52]。

2.3 调控植物体内离子平衡

AMF 和PGPR 可通过截留Na+以缓解离子毒害。AMF 可以将Na+截留在根外菌丝中,抑制其从根向地上部的转运[53]。PGPR 可在根际分泌胞外多糖(exopolysaccharides, EPS),其能够通过羟基、羧基和磷酰基等各类官能团形成庞大的生物膜,在根际微域阻隔Na+进入植物体,进而降低离子毒害[29]。此外,AMF 和PGPR 还通过调控K+转运蛋白(HKT)和Na+/H+逆向转运蛋白(NHX) 的特异性表达,并调节SOS 途径基因的表达,协同缓解离子毒害。例如,解淀粉芽孢杆菌SQR9 可以调控玉米体内与Na+外排相关基因(HKT1、NHX1、NHX2 和NHX3) 表达,将Na+排到细胞外[54−55]。AMF 可以通过增加OsSOS1OsHKT2;1 两类基因的表达促进Na+的排出,并且上调水稻中的OsNHX3 将Na+区域化隔离到根系细胞的液泡中,减少向地上部的转运[56−59]。

2.4 缓解渗透胁迫

AMF 和PGPR 可能通过促进植物体内的碳水化合物、胺、氨基酸及其衍生物等渗透调节物质的合成来缓解渗透胁迫,如脯氨酸、甜菜碱、海藻糖、有机酸和可溶性糖等[29, 47, 60−61]。其中,脯氨酸是植物体内一种重要的渗透保护物质,可通过稳定膜和蛋白亚结构、增加胞内溶质浓度来增加植物对盐的耐受性。Bharti 等[62]发现接种PGPR (Bacillus pumilus、Halomonas desiderata 等) 处理,野薄荷叶片中的脯氨酸含量显著提升。同时,在拟南芥上接种绿脓假单胞菌肠杆菌(Enterobacter sp. EJ01) 使植株叶片中脯氨酸合成相关基因P5CS1 和P5CS2 均表达上调[63]。关于植物遭受盐胁迫时AMF 通过分泌渗透调节物质帮助植物抵抗渗透胁迫的分子机制还缺乏证据。例如,在低盐条件下,莴苣接种菌根真菌Rhizophagusintraradices 后,其脯氨酸合成酶的调控基因P5CS 表达上调,但在高盐条件下P5CS 基因的表达量不受AMF 影响[ 6 4 ]。然而,目前仍缺乏关于PGPR 或AMF 直接促进植物合成渗透调节物质的直接证据。

2.5 调节植物抗氧化防御机制

AMF 和PGPR 均可以调控植物体内的抗氧化酶与非酶抗氧化物的活性。在抗氧化酶方面,AMF 和PGPR 能分泌清除ROS 的SOD、CAT、POD 和APX等抗氧化酶,减轻氧化损伤[65]。在抗氧化剂方面,二者能够提高如AsA、GSH 等的含量,从而阻止自由基和膜质脂肪酸相互作用,增加细胞膜稳定性,增强植物细胞的抗氧化能力。例如,Kim 等[63]发现盐胁迫下接种绿脓假单胞菌肠杆菌(Enterobacter sp. EJ01)的拟南芥中APX 含量比对照高11 倍。AMF 还能诱导上调抗坏血酸-谷胱甘肽(AsA-GSH) 循环相关酶的表达,使植株体内保持较高的抗氧化剂含量,阻止自由基破坏膜质脂肪酸[63−69]。

2.6 增强植物的光合作用

盐胁迫下AMF 和PGPR 均能促进植物体内光合作用相关基因的表达来提高植物的光合作用。例如,在盐胁迫下,AMF 提高了光反应核心亚基蛋白合成基因RppsbA 和RppsbD 的表达量,提高了植株光反应速率,且当PSⅡ反应中心的D1 和D2 蛋白降解时,AMF 对这2 个基因的上调,可以使接种AMF 的刺槐中PSⅡ有更好的修复能力[70]。同时,接种AMF 后,植物体中尿卟啉原脱羧酶(UROD)、叶绿素还原酶(NYC) 和叶绿素合成酶(CHLG) 等一些调控叶绿素合成的蛋白的基因显著上调[71]。在小麦、番茄、玉米、拟南芥和苜蓿等植物上接种PGPR 发现有同样的效果[54, 72]。接种解淀粉芽孢杆菌FZB42后,拟南芥中与光合作用相关的基因表达上调[41]。

3 AMF-PGPR 互作协同提高耐盐机制

目前对于微生物增强植物耐盐的认识大多局限于单菌的耐盐促生功能,但是在土壤中,微生物之间的协同作用更利于植物的生长。通过Web of science核心合集数据库搜索,以“AMF” and “saline” and“PGPR” or “AMF” and “salt” and “PGPR”为检索词,文献类型选择“Article”和“Review”,共检索出已发表的文献仅58 篇,表明盐土环境下AMF+PGPR联合效应的研究仍然相对较少,且多集中在优化植物生长、改善土壤微生物群落结构、促进菌根侵染等方面。

3.1 AMF 和PGPR 对盐胁迫下植物生长的影响

目前AMF 和PGPR 联合接种对于植物生长和耐盐性的影响多集中于农作物。研究发现,AMF 和PGPR 互作提高了水稻(Oryza sativa L)、高粱(Sorghumbicolor)、玉米(Zea mays L.)、豆类、油菜(Brassicacampestris L.) 和番茄等作物的生长和抗盐性。在大田研究中,二者联合接种可使作物产量增加约30%~40%[ 7 3 − 7 8 ]。例如,在水稻田盐土上双接种AMF 和PGPR,通过改善根际环境,促进植物吸收水分来缓解生长抑制,双接种水稻的分蘖数、穗数和每穗粒数及产量提升最高,在正常土壤和盐土上产量分别提高了23%~44.5% 和32.5%~56%[79]。然而,当在不同试验田进行试验时,AMF 和PGPR 共接种时,发现在Kolli Hills 试验田中小米和木豆的作物产量提升了128%,但在Bangalore 试验田增产效果不显著,这可能与作物种植方式、环境条件、接菌菌种以及植物种类有关[80]。

在碱蓬( S u a e d a g l a u c a )、高羊茅( F e s t u c aarundinacea) 和白刺(Nitraria tangutorum Bobrov) 等盐生植物上,AMF 和PGPR 的促生作用显著[81]。在盐碱地环境下,在碱蓬上单独接种AMF 或PGPR 的效果低于联合接种,联合接种显著促进了菌根定殖,提高了光合性能、气孔调节能力,降低了盐分对植物幼苗的不利影响[82−83]。

3.2 AMF 和PGPR 协同调控植物抗盐机制

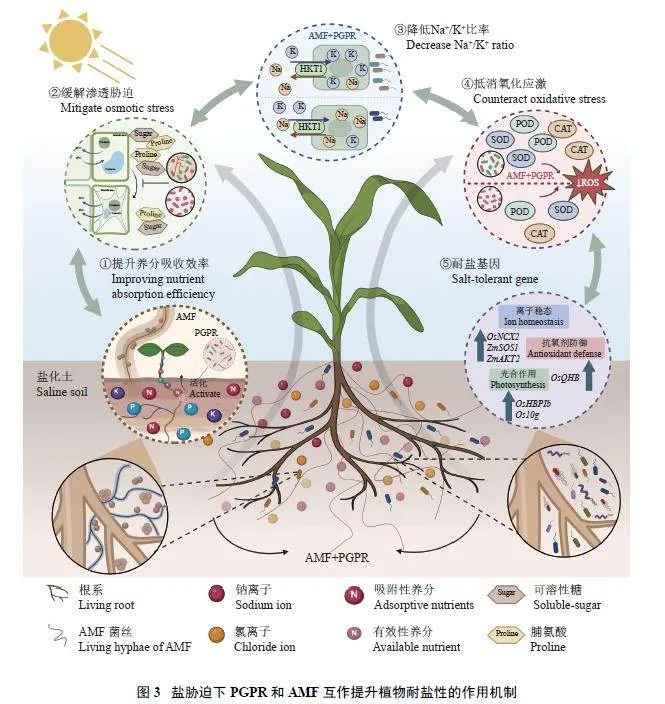

关于AMF 和PGPR 联合接种促进植物生长及帮助植物抗胁迫机制方面的研究,主要集中在土壤养分活化、植物生理生化变化、调节植物耐盐基因表达和二者直接互作的界面机制等方面(图3)。

1) 在养分活化方面,PGPR 直接提高土壤养分的有效性,而AMF 一方面可将PGPR 通过菌丝网络运输到养分(如有机磷) 富集斑块活化养分,同时也可直接吸收养分[84]。例如,Chen 等[74]发现单独接种Rhizophagus irregularis 对玉米生长无显著促进,但由于PGPR 提高了AMF 的侵染率,扩大养分吸收范围,可以有效提高玉米的生物量。同时,AMF 提高PGPR 分泌胞外酶的活性,而PGPR 也可增强AMF在植物根系表面的定殖。在油菜籽上单独和联合接种枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis) 和Rhizophagusintraradice,联合接种相比于单独接种显著提高了碱性磷酸酶、β-葡萄糖苷酶和脱氢酶等土壤胞外酶活性,改善土壤养分循环功能[85]。

2) 在植物生理生化方面,AMF 和PGPR 的协同作用在维持K+和Na+离子稳态、调节细胞内外渗透平衡和清除ROS 方面有显著效果[86]。例如,在盐胁迫环境中,联合接种Bacillus subtilis 和Funneliformismosseae 增加了植物体内原花青素、类黄酮、抗坏血酸、SOD、APX 的含量,同时增加总可溶性糖和蛋白质[87],提升了番茄的总抗氧化能力。在研究单独和双接种AMF (Funneliformis mosseae) 和固氮菌(Sinorhizobium meliloti) 对苜蓿的影响时,发现双接种处理中叶片蛋白质和脯氨酸含量显著最高,根系和叶片中钠离子含量最低,且结瘤量(每株结瘤数和根瘤菌重量) 最高[ 7 5 ]。在种植水稻的盐土上双接种Pseudomonas putida strain S34、Pseudomonasfluorescens strain R167 和Rhizophagus irregularis,可通过降低水稻的CAT 活性,提高脯氨酸含量和清除活性氧来降低其对作物生长限制[79]。

3) 在植物耐盐基因方面,目前已挖掘出大量耐盐关键基因及调控网络,如钠离子通道、ABA 信号和SOS 通路的上调提高了植物对高盐碱胁迫的抗性。联合接种AMF 和PGPR 可诱导相关耐盐基因的表达,例如,研究发现水稻的多种过氧化物酶基因受OsQHB 调控,导致水稻中ROS 清除酶活性更高,MDA 积累更低[ 8 8 ]。盐胁迫下AMF (Funneliformismossea) 和两种PGPR (Piriformospora indica 和Agrobacterium rhizogenes) 联合接种处理,水稻的OsQHB、OsHBP1b、OsNCX2 等与抗氧化酶合成、光合作用和调控离子稳态的相关基因表达量上调[89]。联合接种AMF 和孢子表面细菌能显著提高ZmAKT2、ZmSOS1 和ZmSKOP 等离子稳态相关基因的表达,提高水稻对盐碱胁迫的适应性[90]。另外,接种AMF处理促进了小麦根系分泌物中苯并恶嗪类代谢物的释放,诱导增强PGPR 的趋化作用[91]。虽然AMF 和PGPR 在调控植物基因表达方面已取得了一定的研究进展,但AMF 及PGPR 对植物体内众多基因表达过程的调控机制尚不明确。

4) 在AMF 和PGPR 直接互作的界面机制方面,AMF 和PGPR 在植物根际微域内发生互作[92]。在与植物漫长的协同进化过程中,AMF 失去了腐生功能,无法通过分泌胞外酶来直接活化土壤中复杂的有机化合物,难以利用土壤有机态的养分[93−94]。然而AMF 的菌丝可以作为土壤细菌的栖息场所,通过释放菌丝分泌物吸引一些假单胞菌和芽孢杆菌在菌丝际定殖,这些细菌可产生有机酸和分泌磷酸酶等活化土壤中的磷,这些微生物同时可以通过释放挥发性物质来调控AMF 孢子的萌发,促进菌丝生长和菌根定殖,增强养分活化,达到抗盐促生的目的[95]。

盐胁迫下二者互作过程中,AMF 菌丝可能发挥了“高速公路”的作用,AMF 的根外菌丝可以将溶磷菌运输至富含有机磷的斑块[83]。同样的,AMF 可使PGPR 附着于菌丝表面并沿其游动至盐分较低/生态位适宜的区域;或者将植物地上部光合作用获取的碳源,通过海藻糖、果糖等菌丝分泌物的方式释放到土壤中,驱动PGPR 沿着菌丝趋化运动,最终定殖于菌丝表面。这个过程可能是复杂的化学和分子水平的互作。例如,菌丝可以将PGPR 分解的养分(如氮、磷) 运输至植物根细胞,并且菌丝介导的细菌运动可以促进细菌细胞间的水平基因转移,从而推动PGPR 的快速进化,以适应胁迫环境并发挥功能,从而间接协助植物耐盐[96−98]。反过来,细菌对AMF 的作用机制还不清楚,例如PGPR 能否通过代谢物刺激菌丝细胞壁代谢或细胞膜形成,促使菌丝固定土壤溶液中的盐基离子仍未可知[99−100]。

这些研究结果(表1) 表明,PGPR 和AMF 双接种能够显著降低盐分对幼苗的不利影响,为提升植物抗盐胁迫能力奠定基础,然而,植物生长受到土壤条件、真菌和细菌群落的多重调节,其影响因素还取决于植物与微生物之间的功能相容性以及AMF和PGPR 的特定组合效果。

4 结论与展望

植物−微生物以及微生物−微生物的互作关系一直是农业生命科学领域的研究热点。综上所述,AMF与PGPR 联合提高植物耐盐碱能力的研究还刚起步,未来还需加强的研究方向包括:

1) 盐碱地中AMF 与PGPR 在多重胁迫效应下的互作机制研究。盐碱地存在高盐和高碱等类型,有机质含量低,土壤结构差,同时存在多种胁迫因素。目前有关在盐碱地土壤AMF 和PGPR 互作的研究主要集中在盐胁迫方面,对于其他胁迫,如Na2SO4盐胁迫、NaHCO3 和Na2CO3 碱胁迫以及盐碱混合胁迫的报道相对较少。因此,未来研究需要综合考虑多种胁迫条件下微生物互作的效果和机制。

2) 探索植物−微生物互作过程中的关键信号通路和挖掘植物主效耐盐碱基因。其中,组学技术如转录组学、宏蛋白质组学、代谢组学有利于深入挖掘微生物间的物质传递和信号交流;利用CRISPR/Cas9 基因编辑技术和基因沉默技术等,研究AMF和PGPR 的关键耐盐基因的具体功效。理想的耐盐作物需要在保持抗逆能力的同时稳定产量,但目前仅依靠分子技术难以优化作物的生长−抗逆权衡,可以通过分子设计育种增强作物抗性,然后利用AMF与PGPR 改善作物生长环境,可能是一个重要的突破口。

3) 盐碱胁迫条件下AMF 与菌丝际细菌互作在作物生长中的应用潜力。AMF 庞大的根外菌丝网络可以与土壤中功能细菌形成互惠关系,菌丝特异性招募并构建菌丝际核心微生物组,弥补AMF 缺失的关键功能基因。然而,目前关于AMF 菌丝际的研究大多集中在养分吸收方面,对AMF−菌丝际细菌互作帮助植物抵御非生物胁迫的研究偏少。未来应利用现代分子生态学的研究手段,监测盐碱胁迫下根际微生物组及菌丝际细菌的动态变化,并结合合成生物学的方法构建耐盐碱合成菌群,建立菌丝际核心微生物组、AMF 和植物表型之间的互惠关系,以改良作物根际微环境,促进作物在盐碱土壤环境下的养分获取、水分吸收,最终提高作物产量。

4) 构建功能互补型的合成菌群并研发相关微生物菌剂。目前,盐碱地物理和化学改良技术已有较多的研究,但盐碱地理化修复技术耦合微生物产品,系统提升盐碱地产能的相关研究较少,且大多是在受控的生长室或温室条件下进行的。当前合成菌群已被广泛应用于环境治理、人体健康和工业生产领域,未来需要构建并利用AMF 和PGPR 的合成菌群研发抗盐促生的微生物菌剂,结合种子包衣/颗粒技术,配以合理的农学管理措施,系统解决耐盐碱合成微生物定殖及功能高效稳定问题。

参 考 文 献:

[ 1 ]冯保清, 崔静, 吴迪, 等. 浅谈西北灌区耕地盐碱化成因及对策[J].中国水利, 2019, (9): 43−46.

Feng B Q, Cui J, Wu D, et al. Preliminary studies on causes ofsalinization and alkalinization in irrigation districts of northwestChina and countermeasures[J]. China Water Resources, 2019, (9):43−46.

[ 2 ]Chernousenko G, Pankova E, Kalinina N, et al. Salt-affected soils ofthe Barguzin depression[J]. Eurasian Soil Science, 2017, 50:646−663.。

[ 3 ] Akbar A, Han B, Khan A H, et al. A transcriptomic study reveals salt stress alleviation in cotton plants upon salt tolerant PGPRinoculation[J]. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 2022, 200:104928.

[ 4 ]Li X G, Jousset A, de Boer W, et al. Legacy of land use historydetermines reprogramming of plant physiology by soil microbiome[J]. The ISME Journal, 2019, 13(3): 738−751.

[ 5 ]Allsup C M, George I, Lankau R A. Shifting microbial communitiescan enhance tree tolerance to changing climates[J]. Science, 2023,380: 835−840.

[ 6 ]罗佳煜, 宋瑞清, 邓勋, 等. PGPR与外生菌根菌互作对樟子松促生作用及根际微生态环境的影响[J]. 中南林业科技大学学报, 2021,41(9): 22−34.

Luo J Y, Song R Q, Deng X, et al. PGPR interacts with ectomycorrhizalfungi to promote growth of Pinus sylvestnis var. mongolica and toeffect of rhizosphere microecological environment[J]. Journal ofCentral South University of Forestry and Technology, 2021, 41(9):22−34.

[ 7 ]Chen J, Zhang H P, Feng M F, et al. Transcriptome analysis ofwoodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) response to the infection bystrawberry vein banding virus (SVBV)[J]. Virology Journal, 2016,13: 128.

[ 8 ]Sasse J, Martinoia E, Northen T. Feed your friends: Do plantexudates shape the root microbiome?[J]. Trends in Plant Science,2018, 23(1): 25−41.

[ 9 ]Zhang C, van der Heijden M G, Dodds B K, et al. A tripartitebacterial-fungal-plant symbiosis in the mycorrhiza-shapedmicrobiome drives plant growth and mycorrhization[J]. Microbiome,2024, 12(1): 13.

[ 10 ]Munns R, Schachtman D, Condon A. The significance of a twophasegrowth response to salinity in wheat and barley[J]. Functional Plant Biology, 1995, 22(4): 561−569.

[ 11 ]Ilangumaran G, Smith D L. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria inamelioration of salinity stress: A systems biology perspective[J].Frontiers in Plant Science, 2017, 8: 275185.

[ 12 ]Qin Y, Druzhinina I S, Pan X Y, Yuan Z L. Microbially mediatedplant salt tolerance and microbiome-based solutions for salineagriculture[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2016, 34(7): 1245−1259.

[ 13 ]Razzaq A, Ali A, Safdar L B, et al. Salt stress induces physiochemicalalterations in rice grain composition and quality[J]. Journal of FoodScience, 2020, 85(1): 14−20.

[ 14 ]Qin H, Huang R. The phytohormonal regulation of Na+/K+ andreactive oxygen species homeostasis in rice salt response[J].Molecular Breeding, 2020, 40(5): 47.

[ 15 ]Zhu J K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants[J]. Cell,2016, 167(2): 313−324.

[ 16 ]Sun J K, He L, Li T. Response of seedling growth and physiology ofSorghum bicolor (L.) Moench to saline-alkali stress[J]. PLoS ONE,2019, 14(7): e0220340.

[ 17 ]Oda Y, Kobayashi N I, Tanoi K, et al. T-DNA tagging-based gainof-function of OsHKT1; 4 reinforces Na exclusion from leaves andstems but triggers Na toxicity in roots of rice under salt stress[J].International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2018, 19(1): 235.

[ 18 ]Yang Y Q, Guo Y. Unraveling salt stress signaling in plants[J].Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 2018, 60(9): 796−804.

[ 19 ]Li B, Tester M, Gilliham M. Chloride on the move[J]. Trends inPlant Science, 2017, 22(3): 236−248.

[ 20 ]Li B, Qiu J E, Jayakannan M, et al. AtNPF2. 5 modulates chloride(Cl−) efflux from roots of Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Frontiers in PlantScience, 2017, 7: 2013.

[ 21 ]Cubero-Font P, Maierhofer T, Jaslan J, et al. Silent S-type anionchannel subunit SLAH1 gates SLAH3 open for chloride root-toshoottranslocation[J]. Current Biology, 2016, 26(16): 2213−2220.

[ 22 ]Teakle N L, Tyerman S D. Mechanisms of Cl− transport contributingto salt tolerance[J]. Plant, Cell and Environment, 2010, 33(4):566−589.

[ 23 ]Gierth M, Mäser P, Schroeder J I. The potassium transporterAtHAK5 functions in K+ deprivation-induced high-affinity K+uptake and AKT1 K+ channel contribution to K+ uptake kinetics inArabidopsis roots[J]. Plant Physiology, 2005, 137(3): 1105−1114.

[ 24 ]Parihar M, Rakshit A, Rana K, et al. A consortium of arbuscularmycorrizal fungi improves nutrient uptake, biochemical response,nodulation and growth of the pea (Pisum sativum L.) under saltstress[J]. Rhizosphere, 2020, 15: 100235.

[ 25 ]Meloni D A, Oliva M A, Martinez C A, Cambraia J. Photosynthesisand activity of superoxide dismutase, peroxidase and glutathionereductase in cotton under salt stress[J]. Environmental and ExperimentalBotany, 2003, 49(1): 69−76.

[ 26 ]Das K, Roychoudhury A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) andresponse of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmentalstress in plants[J]. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 2014, 2: 53.

[ 27 ]Yang Y, Guo Y. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediatingplant salt-stress responses[J]. New Phytologist, 2018, 217(2): 523−539.

[ 28 ]Xing L J, Zhu M, Luan M D, et al. miR169q and NUCLEARFACTOR YA8 enhance salt tolerance by activating PEROXIDASE1expression in response to ROS[J]. Plant Physiology, 2022, 188(1):608−623.

[ 29 ]Etesami H, Beattie G A. Mining halophytes for plant growthpromotinghalotolerant bacteria to enhance the salinity tolerance ofnon-halophytic crops[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 148.

[ 30 ]Koutika L-S, Mareschal L, Epron D. Soil P availability undereucalypt and acacia on Ferralic Arenosols, republic of the Congo[J].Geoderma Regional, 2016, 7(2): 153−158.

[ 31 ]Upadhyay S, Singh D. Effect of salt-tolerant plant growthpromotingrhizobacteria on wheat plants and soil health in a salineenvironment[J]. Plant Biology, 2015, 17(1): 288−293.

[ 32 ]Zhang J H, Hussain S, Zhao F T, et al. Effects of Azospirillumbrasilense and Pseudomonas fluorescens on nitrogen transformationand enzyme activity in the rice rhizosphere[J]. Journal of Soils andSediments, 2018, 18: 1453−1465.

[ 33 ]向丹, 徐天乐, 李欢, 陈保冬. 丛枝菌根真菌的生态分布及其影响因子研究进展[J]. 生态学报, 2017, 37(11): 3597−3606.

Xiang D, Xu T L, Li H, Chen B D. Ecological distribution ofarbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and the influencing factors[J]. ActaEcologica Sinica, 2017, 37(11): 3597−3606.

[ 34 ]Wang L, George T S, Feng G. Concepts and consequences of thehyphosphere core microbiome for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungalfitness and function[J]. New Phytologist, 2024, 242(4): 1529−1533.

[ 35 ]Li X, Zhao R T, Li D D, et al. Mycorrhiza-mediated recruitment ofcomplete denitrifying Pseudomonas reduces N2O emissions fromsoil[J]. Microbiome, 2023, 11(1): 45.

[ 36 ]Basu S, Rabara R C, Negi S. AMF: The future prospect forsustainable agriculture[J]. Physiological and Molecular PlantPathology, 2018, 102: 36−45.

[ 37 ]Al-Arjani A-B F, Hashem A, Abd_Allah E F. Arbuscular mycorrhizalfungi modulates dynamics tolerance expression to mitigate droughtstress in Ephedra foliata Boiss[J]. Saudi Journal of BiologicalSciences, 2020, 27(1): 380−394.

[ 38 ]贺忠群, 贺超兴, 闫妍, 等. 盐胁迫下丛枝菌根真菌对番茄吸水及水孔蛋白基因表达的调控[J]. 园艺学报, 2011, 38(2): 273−280.

He Z Q, He C X, Yan Y, et al. Regulative effect of arbuscularmycorrhizal fungi on water absorption and expression of aquaporingenes in tomato under salt stress[J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica, 2011,38(2): 273−280.

[ 39 ]Motaleb N A, Elhady S, Ghoname A. AMF and Bacillus megateriumneutralize the harmful effects of salt stress on bean plants[J].Gesunde Pflanz, 2020, 72(1): 29−39.

[ 40 ]Kakouridis A, Hagen J A, Kan M P, et al. Routes to roots: Directevidence of water transport by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to hostplants[J]. New Phytologist, 2022, 236(1): 210−221.

[ 41 ]Liu S F, Hao H T, Lu X, et al. Transcriptome profiling of genesinvolved in induced systemic salt tolerance conferred by Bacillusamyloliquefaciens FZB42 in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. ScientificReports, 2017, 7(1): 10795.

[ 42 ]贺忠群, 李焕秀, 汤浩茹, 等. 丛枝菌根真菌对 NaCl 胁迫下番茄内源激素的影响[J]. 核农学报, 2010, 24(5): 1099−1104.

He Z Q, Li H X, Tang H R, et al. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizalfungi on tomato endogenous under NaCl stress[J]. Journal ofNuclear Agricultural Sciences, 2010, 24(5): 1099−1104.

[ 43 ]Bharti N, Pandey S S, Barnawal D, et al. Plant growth promotingrhizobacteria Dietzia natronolimnaea modulates the expression ofstress responsive genes providing protection of wheat from salinitystress[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 1−16.

[ 44 ]Estrada B, Beltrán-Hermoso M, Palenzuela J, et al. Diversity ofarbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the rhizosphere of Asteriscusmaritimus (L.) Less., a representative plant species in arid and salineMediterranean ecosystems[J]. Journal of Arid Environments, 2013,97: 170−175.

[ 45 ]Abdelhameed R E, Metwally R A. Mitigation of salt stress by dualapplication of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and salicylic acid[J].Agrochimica: International Journal of Plant Chemistry, Soil Scienceand Plant Nutrition of the University of Pisa, 2018, 62(4): 353−366.

[ 46 ]Evelin H, Giri B, Kapoor R. Ultrastructural evidence for AMFmediated salt stress mitigation in Trigonella foenum-graecum[J].Mycorrhiza, 2013, 23: 71−86.

[ 47 ]Bhattacharyya D, Yu S-M, Lee Y H. Volatile compounds fromAlcaligenes faecalis JBCS1294 confer salt tolerance in Arabidopsisthaliana through the auxin and gibberellin pathways and differentialmodulation of gene expression in root and shoot tissues[J]. PlantGrowth Regulation, 2015, 75: 297−306.

[ 48 ]Vaishnav A, Kumari S, Jain S, et al. Putative bacterial volatilemediatedgrowth in soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill) andexpression of induced proteins under salt stress[J]. Journal ofApplied Microbiology, 2015, 119(2): 539−551.

[ 49 ]Singh R P, Shelke G M, Kumar A, Jha P N. Biochemistry andgenetics of ACC deaminase: A weapon to “stress ethylene”produced in plants[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 6: 937.

[ 50 ]Camoni L, Visconti S, Aducci P, Marra M. 14-3-3 proteins in planthormone signaling: Doing several things at once[J]. Frontiers inPlant Science, 2018, 9: 297.

[ 51 ]Vives-Peris V, Gómez-Cadenas A, Pérez-Clemente R M. Salt stressalleviation in citrus plants by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteriaPseudomonas putida and Novosphingobium sp.[J]. Plant CellReports, 2018, 37(11): 1557−1569.

[ 52 ]del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M, Glick B R, Santoyo G. ACCdeaminase in plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB): An efficientmechanism to counter salt stress in crops[J]. MicrobiologicalResearch, 2020, 235: 126439.

[ 53 ]Kong L, Gong X W, Zhang X L, et al. Effects of arbuscularmycorrhizal fungi on photosynthesis, ion balance of tomato plantsunder saline-alkali soil condition[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition,2020, 43(5): 682−698.

[ 54 ]Chen L, Liu Y P, Wu G W, et al. Beneficial rhizobacterium Bacillusamyloliquefaciens SQR9 induces plant salt tolerance throughspermidine production[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions,2017, 30(5): 423−432.

[ 55 ]Chen L, Liu Y P, Wu G W, et al. Induced maize salt tolerance byrhizosphere inoculation of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9[J].Physiologia Plantarum, 2016, 158(1): 34−44.

[ 56 ]Lin H X, Yang Y Q, Quan R D, et al. Phosphorylation of SOS3-LIKE CALCIUM BINDING PROTEIN8 by SOS2 protein kinasestabilizes their protein complex and regulates salt tolerance inArabidopsis[J]. The Plant Cell, 2009, 21(5): 1607−1619.

[ 57 ]Zhang X H, Han C Z, Gao H M, Cao Y P. Comparativetranscriptome analysis of the garden asparagus (Asparagusofficinalis L.) reveals the molecular mechanism for growth witharbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under salinity stress[J]. PlantPhysiology and Biochemistry, 2019, 141: 20−29.

[ 58 ]Porcel R, Aroca R, Azcon R, Ruiz-Lozano J M. Regulation of cationtransporter genes by the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in riceplants subjected to salinity suggests improved salt tolerance due toreduced Na+ root-to-shoot distribution[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2016, 26:673−684.

[ 59 ]Haque S I, Matsubara Y I. Salinity tolerance and sodium localizationin mycorrhizal strawberry plants[J]. Communications in SoilScience and Plant Analysis, 2018, 49(22): 2782−2792.

[ 60 ]Li H Q, Jiang X W. Inoculation with plant growth-promotingbacteria (PGPB) improves salt tolerance of maize seedling[J].Russian Journal of Plant Physiology, 2017, 64: 235−241.

[ 61 ]Rojas-Tapias D, Moreno-Galván A, Pardo-Díaz S, et al. Effect ofinoculation with plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) onamelioration of saline stress in maize (Zea mays)[J]. Applied SoilEcology, 2012, 61: 264−272.

[ 62 ]Bharti N, Barnawal D, Awasthi A, et al. Plant growth promotingrhizobacteria alleviate salinity induced negative effects on growth,oil content and physiological status in Mentha arvensis[J]. ActaPhysiologiae Plantarum, 2014, 36: 45−60.

[ 63 ]Kim K, Jang Y J, Lee S M, et al. Alleviation of salt stress byEnterobacter sp. EJ01 in tomato and Arabidopsis is accompanied byup-regulation of conserved salinity responsive factors in plants[J].Molecules and Cells, 2014, 37(2): 109−117.

[ 64 ]Jahromi F, Aroca R, Porcel R, Ruiz-Lozano J M. Influence ofsalinity on the in vitro development of Glomus intraradices and onthe in vivo physiological and molecular responses of mycorrhizallettuce plants[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2008, 55: 45−53.

[ 65 ]Kong Z, Glick B R. The role of plant growth-promoting bacteriain metal phytoremediation[J]. Advances in Microbial Physiology,2017, 71: 97−132.

[ 66 ]Abeer H, Abd_Allah E F, Alqarawi A A, Egamberdieva D.Induction of salt stress tolerance in cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.)Walp. ] by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi[J]. Legume Research-AnInternational Journal, 2015, 38(5): 579−588.

[ 67 ]Santander C, Ruiz A, García S, et al. Efficiency of two arbuscularmycorrhizal fungal inocula to improve saline stress tolerance inlettuce plants by changes of antioxidant defense mechanisms[J].Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2020, 100(4):1577−1587.

[ 68 ]孙思淼, 常伟, 宋福强. 丛枝菌根真菌提高盐胁迫植物抗氧化机制的研究进展[J]. 应用生态学报, 2020, 31(10): 3589−3596.

Sun S M, Chang W, Song F Q. Mechanism of arbuscularmycorrhizal fungi improve the oxidative stress to the host plantsunder salt stress: A review[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology,2020, 31(10): 3589−3596.

[ 69 ]Radhakrishnan R, Khan A L, Kang S M, Lee I J. A comparativestudy of phosphate solubilization and the host plant growthpromotion ability of Fusarium verticillioides RK01 and Humicolasp. KNU01 under salt stress[J]. Annals of Microbiology, 2015, 65:585−593.

[ 70 ]陈婕. 丛枝菌根真菌(AMF)提高刺槐耐盐性机制的研究[D]. 陕西杨凌: 西北农林科技大学博士学位论文, 2018.

Chen J. Study on the mechanism of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi(AMF) in improving the salt tolerance of Robinia pseudoacacia[D].Yangling, Shaanxi: PhD Dissertation of Northwest Aamp;F University,2018.

[ 71 ]Wang Y N, Lin J X, Huang S C, et al. Isobaric tags for relative andabsolute quantification-based proteomic analysis of Puccinelliatenuiflora inoculated with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reveal stressresponse mechanisms in alkali-degraded soil[J]. Land Degradationamp; Development, 2019, 30(13): 1584−1598.

[ 72 ]Han Q Q, Lü X P, Bai J P, et al. Beneficial soil bacterium Bacillussubtilis (GB03) augments salt tolerance of white clover[J]. Frontiersin Plant Science, 2014, 5: 115855.

[ 73 ]Karimi R, Noori A. Streptomyces rimosus rhizobacteria and Glomusmosseae mycorrhizal fungus inoculation alleviate salinity stress ingrapevine through morphophysiological changes and nutritionalbalance[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2022, 305: 111433.

[ 74 ]Chen Q, Deng X H, Elzenga J T M, et al. Effect of soil bacteriomeson mycorrhizal colonization by Rhizophagus irregularis—interactiveeffects on maize (Zea mays L.) growth under salt stress[J]. Biologyand Fertility of Soils, 2022, 58(5): 515−525.

[ 75 ]Zhou W, Zhang M M, Tao K Z, Zhu X C. Effects of arbuscularmycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria ongrowth and reactive oxygen metabolism of tomato fruits under lowsaline conditions[J]. Biocell, 2022, 46(12): 2575−2582.

[ 76 ]Afrangan F, Kazemeini S A, Alinia M, Mastinu A. Glomusversiforme and Micrococcus yunnanensis reduce the negativeeffects of salinity stress by regulating the redox state and ionhomeostasis in Brassica napus L. crops[J]. Biologia, 2023, 78(11):3049−3061.

[ 77 ]Younesi O, Moradi A. Effects of plant growth-promotingrhizobacterium (PGPR) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus(AMF) on antioxidant enzyme activities in salt-stressed bean(Phaseolus vulgaris L.)[J]. Agriculture (Pol'nohospodárstvo),2014, 60(1): 10−21.

[ 78 ]Yadav R, Ror P, Rathore P, et al. Bacillus subtilis CP4, isolatedfrom native soil in combination with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungipromotes biofortification, yield and metabolite production in wheatunder field conditions[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2021,131(1): 339−359.

[ 79 ]Norouzinia F, Ansari M H, Aminpanah H, Firozi S. Alleviation ofsoil salinity on physiological and agronomic traits of rice cultivarsusing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Pseudomonas strains underfield conditions[J]. Revista de Agricultura Neotropical, 2020, 7(1):25−42.

[ 80 ][ 80 ] Diagne N, Ndour M, Djighaly P I, et al. Effect of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi(AMF) on salt stress tolerance of Casuarina obesa (Miq.)[J].Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2020, 4: 601004.

[ 81 ]Li X, Zhang Z C, Luo J Q, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungiand nitrilotriacetic acid regulated Suaeda salsa growth in Cdcontaminatedsaline soil by driving rhizosphere bacterial assemblages[J]. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 2022, 193: 104669.

[ 82 ]Liu H, Tang H M, Ni X Z, et al. Interactive effects of Epichloëendophytes and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on saline-alkali stresstolerance in tall fescue[J]. Front Microbiology, 2022, 13: 855890.

[ 83 ]Pan J, Huang C H, Peng F, et al. Synergistic combination ofarbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promotingrhizobacteria modulates morpho-physiological characteristics andsoil structure in Nitraria tangutorum bobr. under saline soilconditions[J]. Research in Cold and Arid Regions, 2022, 14(6):393−402.

[ 84 ]Jiang F Y, Zhang L, Zhou J C, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungienhance mineralisation of organic phosphorus by carrying bacteriaalong their extraradical hyphae[J]. New Phytologist, 2021, 230(1):304−315.

[ 85 ]Hidri R, Mahmoud O M-B, Debez A, et al. Modulation of C: N: Pstoichiometry is involved in the effectiveness of a PGPR and AMfungus in increasing salt stress tolerance of Sulla carnosa Tunisianprovenances[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2019, 143: 161−172.

[ 86 ]Reginato M, Cenzano A M, Arslan I, et al. Na2SO4 and NaCl saltsdifferentially modulate the antioxidant systems in the highly stresstolerant halophyte Prosopis strombulifera[J]. Plant Physiology andBiochemistry, 2021, 167: 748−762.

[ 87 ]Ashrafi E, Zahedi M, Razmjoo J. Co-inoculations of arbuscularmycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia under salinity in alfalfa[J]. SoilScience and Plant Nutrition, 60(5): 619−629.

[ 88 ]Zhou J H, Qiao J Z, Wang J, et al. OsQHB improves salt toleranceby scavenging reactive oxygen species in rice[J]. Frontiers in PlantScience, 2022, 13: 848891.

[ 89 ]Zhang B, Shi F, Zheng X, et al. Effects of AMF compoundinoculants on growth, ion homeostasis, and salt tolerance-relatedgene expression in Oryza sativa L. under salt treatments[J]. Rice,2023, 16(1): 18.

[ 90 ]Selvakumar G, Shagol C C, Kim K, et al. Spore associated bacteriaregulates maize root K+/Na+ ion homeostasis to promote salinitytolerance during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis[J]. BMC PlantBiology, 2018, 18(1): 109.

[ 91 ]Cameron D D, Neal A L, van Wees S C, Ton J. Mycorrhiza-inducedresistance: More than the sum of its parts?[J]. Trends in PlantScience, 2013, 18(10): 539−545.

[ 92 ]Hidri R, Barea J, Mahmoud O M-B, et al. Impact of microbialinoculation on biomass accumulation by Sulla carnosa provenances,and in regulating nutrition, physiological and antioxidant activitiesof this species under non-saline and saline conditions[J]. Journal ofPlant Physiology, 2016, 201: 28−41.

[ 93 ]Tisserant E, Malbreil M, Kuo A, et al. Genome of an arbuscularmycorrhizal fungus provides insight into the oldest plant symbiosis[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2013, 110(50): 20117−20122.

[ 94 ]Zhang L, Xu M G, Liu Y, et al. Carbon and phosphorus exchangemay enable cooperation between an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungusand a phosphate-solubilizing bacterium[J]. New Phytologist, 2016,210(3): 1022−1032.

[ 95 ]Wang G W, Jin Z X, George T S, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizalfungi enhance plant phosphorus uptake through stimulatinghyphosphere soil microbiome functional profiles for phosphorusturnover[J]. New Phytologist, 2023, 238(6): 2578−2593.

[ 96 ]Castaeda-Gómez L, Powell J R, Pendall E, Carrillo Y. Phosphorusavailability and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi limit soil C cyclingand influence plant responses to elevated CO2 conditions[J].Biogeochemistry, 2022, 160(1): 69−87.

[ 97 ]Wu H W, Cui H L, Fu C X, et al. Unveiling the crucial role of soilmicroorganisms in carbon cycling: A review[J]. Science of the TotalEnvironment, 2023, 909: 168627.

[ 98 ]Simon A, Bindschedler S, Job D, et al. Exploiting the fungalhighway: Development of a novel tool for the in situ isolation of bacteriamigrating along fungal mycelium[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology,2015, 91(11): fiv116.

[ 99 ]Zhang L, Zhou J C, George T S, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungiconducting the hyphosphere bacterial orchestra[J]. Trends in PlantScience, 2022, 27(4): 402−411.

[100]Li H H, Chen X W, Zhai F H, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungusalleviates charged nanoplastic stress in host plants via enhanceddefense-related gene expressions and hyphal capture[J]. EnvironmentalScience and Technology, 2024, 58(14): 6258−6273.

[101]Hashem A, Abd_Allah E, Alqarawi A, et al. Induction ofosmoregulation and modulation of salt stress in Acacia gerrardiiBenth. by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Bacillus subtilis (BERA71)[J]. BioMed Research International, 2016, 1: 6294098.

[102]Pan J, Huang C H, Peng F, et al. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizalfungi (AMF) and plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPR)inoculations on Elaeagnus angustifolia L. in saline soil[J]. Applied Sciences, 2020, 10(3): 945.

[103]Xun F F, Xie B M, Liu S S, Guo C H. Effect of plant growthpromotingbacteria (PGPR) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi(AMF) inoculation on oats in saline-alkali soil contaminated bypetroleum to enhance phytoremediation[J]. Environmental Scienceand Pollution Research, 2015, 22: 598−608.

[104]Rueda-Puente E O, Murillo-Amador B, Castellanos-Cervantes T, etal. Effects of plant growth promoting bacteria and mycorrhizal onCapsicum annuum L. var. aviculare ([Dierbach] D’Arcy andEshbaugh) germination under stressing abiotic conditions[J]. PlantPhysiology and Biochemistry, 2010, 48(8): 724−730.

[105]Toubali S, Meddich A. Role of combined use of mycorrhizae fungiand plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in the tolerance of quinoaplants under salt stress[J]. Gesunde Pflanzen, 2023, 75(5): 1855−1869.

[106]Abd-Alla M H, El-Enany A-W E, Nafady N A, et al. Synergisticinteraction of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae and arbuscularmycorrhizal fungi as a plant growth promoting biofertilizers for fababean (Vicia faba L.) in alkaline soil[J]. Microbiological Research,2014, 169(1): 49−58.

[107]Lee Y, Krishnamoorthy R, Selvakumar G, et al. Alleviation of saltstress in maize plant by co-inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizalfungi and Methylobacterium oryzae CBMB20[J]. Journal of theKorean Society for Applied Biological Chemistry, 2015, 58(4):533−540.

[108]Hidri R, Mahmoud O M-B, Farhat N, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizalfungus and rhizobacteria affect the physiology and performance ofSulla coronaria plants subjected to salt stress by mitigation of ionicimbalance[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 2019,182(3): 451−462.

[109]Gamalero E, Berta G, Massa N, et al. Interactions betweenPseudomonas putida UW4 and Gigaspora rosea BEG9 and theirconsequences for the growth of cucumber under salt-stress conditions[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2010, 108(1): 236−245.

作者简介:

秦敬泽,中国农业大学资源与环境学院博士研究生,主要研究领域为盐碱地土壤改良与菌根生理生态。

张俊伶,中国农业大学资源与环境学院教授,博士生导师。主要从事土壤健康和根际微生物研究方向的工作。在土壤健康和资源可持续利用、微生物多样性和生态功能、土壤生物肥力以及生物肥料等方面也开展了大量的研究工作。主持国家自然科学基金、国家重点研发项目课题,参加国家自然科学基金委创新群体和重点项目、科技部973 项目、农业部公益性行业项目、参加科技部国家重点研发计划中澳可持续农业管理项目、中荷农业绿色发展项目等。相关研究成果发表在Nature Communications、Microbiome、Global Change Biology、EcologyLetters、Environmental Microbiology、New Phytologist 等期刊上。任中国土壤学会土壤健康工作组组长、中国菌物学会内生菌和菌根真菌专业委员会主任、中国植物营养与肥料学会第十届教育工作委员会副主任等。

基金项目:国家自然科学基金联合基金项目(U23A201464)。