Comparison of fungal vs bacterial infections in the medical intensive liver unit: Cause or corollary for high mortality?

Sarah Khan, Hanna Hong, Stephanie Bass, Yifan Wang, Xiao-Feng Wang, Omar T Sims, Christine E Koval,Aanchal Kapoor, Christina C Lindenmeyer

Abstract BACKGROUND Due to development of an immune-dysregulated phenotype, advanced liver disease in all forms predisposes patients to sepsis acquisition, including by opportunistic pathogens such as fungi. Little data exists on fungal infection within a medical intensive liver unit (MILU), particularly in relation to acute on chronic liver failure.AIM To investigate the impact of fungal infections among critically ill patients with advanced liver disease, and compare outcomes to those of patients with bacterial infections.METHODS From our prospective registry of MILU patients from 2018-2022, we included 27 patients with culture-positive fungal infections and 183 with bacterial infections. We compared outcomes between patients admitted to the MILU with fungal infections to bacterial counterparts. Data was extracted through chart review.RESULTS All fungal infections were due to Candida species, and were most frequently blood isolates. Mortality among patients with fungal infections was significantly worse relative to the bacterial cohort (93% vs 52%, P < 0.001). The majority of the fungal cohort developed grade 2 or 3 acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) (90% vs 64%, P = 0.02). Patients in the fungal cohort had increased use of vasopressors (96% vs 70%, P = 0.04), mechanical ventilation (96% vs 65%, P < 0.001), and dialysis due to acute kidney injury (78% vs 52%, P = 0.014). On MILU admission, the fungal cohort had significantly higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (108 vs 91, P = 0.003), Acute Physiology Score (86 vs 65, P = 0.003), and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium scores (86 vs 65, P = 0.041). There was no significant difference in the rate of central line use preceding culture (52% vs 40%, P = 0.2). Patients with fungal infection had higher rate of transplant hold placement, and lower rates of transplant; however, differences did not achieve statistical significance.CONCLUSION Mortality was worse among patients with fungal infections, likely attributable to severe ACLF development. Prospective studies examining empiric antifungals in severe ACLF and associations between fungal infections and transplant outcomes are critical.

Key Words: Fungal; Infection; Sepsis; Acute on chronic liver failure; Intensive care

INTRODUCTION

Advanced liver disease predisposes patients to acquisition of infections. This vulnerability is best described in cirrhosis, through development of a cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction (CAID). Intestinal dysbiosis and disruption of the gut barrier leads to gut inflammation, causing portal and systemic inflammation in cirrhosis patients[1]. Despite persistent immune activation[2-5], converse immunodeficiency develops due to immune exhaustion and senescence in advanced cirrhosis[6]. Immune dysfunction through impaired phagocytosis, complement deficiency, and Kupffer cell disruption mediates this vulnerability to invasive fungal infections[7-9]. Vulnerability due to immune dysfunction is further compounded by management practices that heighten the risk of infections, such as need for invasive monitoring, use of proton-pump inhibitors, frequent procedures such as paracenteses, cardiopulmonary support, and use of corticosteroids[10]. This model of CAID has been extrapolated to other forms of advanced liver disease, including acute states such as acute liver failure and severe alcohol-associated hepatitis[11,12]. This innate immunodeficiency predisposes patients to infections and increased mortality[13,14]. Infections have been shown to be the most common cause of acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF), and development of ACLF in patients with cirrhosis contributes significantly to infection-related mortality[14-16]. Further, infection-triggered ACLF is associated with higher mortality than that triggered by noninfectious causes[17].

This theorized immunodeficient phenotype also predisposes patients to other types of opportunistic pathogens[14,16], including fungal infections. The existing literature on ACLF has predominantly focused on bacterial infections due to their prevalence as the primary triggers of ACLF in Western countries[18]. Invasive fungal infections, however, are emerging as under-recognized significant causes of mortality, particularly in the critical care setting[7,11,16,19]. Recent studies have demonstrated an association between fungal infections with the development of severe ACLF, increased rate of intensive care admission among infected patients, and higher mortality[15,19], when compared with bacterial infections.

Due to this significant impact, there has been a growing interest in further characterizing the impact of fungal infections in cirrhosis[19]. There is limited data comparing outcomes between patients with fungal and bacterial infections among patients with advanced liver disease in the critical care setting, though studies have characterized these for general hospitalizations[20,21]. We aimed to compare mortality and clinical characteristics including laboratory markers, illness severity indices and degree of shock, between patients with fungal and bacterial infections within our Medical Intensive Liver Unit (MILU). Furthermore, we characterized epidemiology of such infections within our MILU.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Study design and definitions

The Cleveland Clinic MILU is a multi-disciplinary care setting designed for daily co-management of patients by hepatology and critical care teams, with a special focus on bridging critically ill patients to transplant. We designed a cohort study comparing patients with fungal and bacterial infections, who were admitted to our MILU between January 2018 to September 2022. To identify a study sample of patients with culture-confirmed infections, we queried our prospectively-curated, longitudinal MILU database for patients with positive cultures. Diagnostic criteria for infections were: positive blood cultures/cultures from sterile sites in combination with clinical symptoms of infection, which were usually treated with antimicrobials in consultation with our infectious disease department[22]. Fungal infections were deemed present if fungi were isolated from blood (candidemia) or other sterile sites (peritoneal fluid), or urine in certain cases. Positive cultures from urinary sources were included as infection if there were clinically associated symptoms and were treated with targeted antifungal agents. One case of tracheitis was included following isolation from tracheal biopsy due to complicated wound infection at a tracheostomy site. For patients with multiple positive sites of fungal culture including blood and non-sterile sites, infection was classified as fungemia. Among patients with bacterial isolates, 15 patients had 2 separate culture-positive instances of infection within the same MILU stay. In such cases, the second instance of infection was used in the mortality analysis. All infection parameters were defined in consultation with our transplant infectious disease department. Multi-drug resistant organisms (MDRO) were defined using previously established guidelines for each isolated organism: resistance to two or more classes of antibiotics for the majority of bacterial pathogens; and resistance to two or more classes of antifungals for fungal pathogens[23-27].

Furthermore, patients were included if they had clinically significant advanced liver disease, as defined by the presence of cirrhosis, acute liver failure, severe alcohol-associated hepatitis, or severe acute liver injury. Cirrhosis was defined either as biopsy-proven bridging fibrosis of the liver or as a composite of clinical signs, laboratory tests, endoscopy and radiologic imaging. Acute liver failure and severe alcohol-associated hepatitis were defined in accordance with the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines[28,29]. Severe acute liver injury was taken as clinically significant hepatic impairment with composite radiologic and laboratory abnormalities not meeting criteria for acute liver failure or alcohol-associated hepatitis. ACLF and organ failures were defined by the European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure (CLIF) Consortium[30]. Exclusion criteria included culture from contaminants or clinically mild liver disease, such as transient liver injury. The Cleveland Clinic Foundation’s institutional review board approved the study protocol as a non-interventional, anonymized study waiving the need for informed consent.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest for this study was mortality from time of onset of infection, which was determined by the date of a positive culture. Mortality was compared between patients with fungal and bacterial infections in the MILU.

Secondary outcomes of interest included need for cardiopulmonary support, development of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, transplant evaluation endpoints and length of stay. Three separate lengths of stay were compared: total stay from hospital admission to discharge/death, time from intensive care unit (ICU) admission to ICU discharge and time from hospital admission to ICU discharge. Outcomes were compared between fungal and bacterial cohorts. Comparisons were also conducted on characteristics of acute illness including labs at infection, illness severity scoring and severity of ACLF, if applicable, at the time of culture. Finally, pre-infection predisposing variables were analyzed for differences between bacterial and fungal cohorts, including circulatory failure requiring hemodynamic support, prior antimicrobial use, and admission scores of illness severity.

Variables and definitions

All variables and outcomes were collected through chart extraction. Patients were identified from our longitudinal, prospective registry of all admissions to the MILU, and eligible cases were extracted from the electronic medical record based on culture positivity. ACLF was defined as suggested by the chronic liver failure consortium (CLIF-C OFs), graded by the number and severity of organ failures after an initial insult[30,31]. Infections were considered to have precipitated ACLF if the date of culture was prior to or on the day of syndrome development. Furthermore, grading of ACLF was done at the time of positive culture. Labs of interest at time points of infection were taken within 3 d prior to or after the date of culture, if unavailable at the date of culture. Stress dose steroid use preceding infection was defined as steroid dosing equivalent to 50 mg of hydrocortisone every 8 h, used for at least 3 d in the preceding 3 months from date of positive culture. MDROs were defined using pre-established criteria by an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance[23,24,26,27]. Elucidation of epidemiology of fungal infection and colonization within our unit to inform antimicrobial protocols was done using individual culture data.

Statistical analysis

Measures of central tendency (means and standard deviations for normally distributed continuous variables, medians and quartiles for non-normally distributed continuous variables) and frequency distributions were used to characterize the sample. Comparisons between fungal and bacterial cohorts were done using Wilcoxon rank sum and Welch’s twosamplet-tests for continuous variables. Pearson’s chi-square and Fischer’s exact tests were used for comparison of categorical variables. A Kaplan-Meier curve was constructed to compare survival from ICU admission. All statistical analyses were conducted using R 4.0.5. Core Team (R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2018. URL http://www.R-project.org/).Pvalues < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted in partnership with biostatisticians from our institution’s department of quantitative health sciences.

RESULTS

Study sample and population characteristics

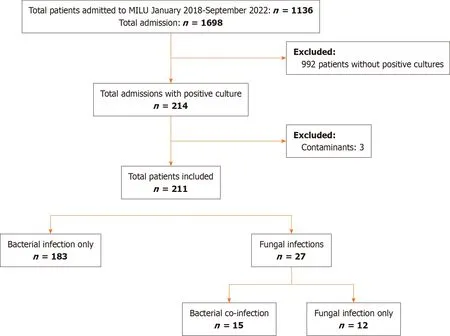

From 2018-2022, 1136 individual patients were treated in the MILU, accounting for 1698 admissions. Of these, we isolated 214 unique patients with positive microbial cultures. Of this population, we further excluded 3 cases with positive cultures as these were clinically treated as contaminants (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Study population and inclusion criteria. MILU: Medical intensive liver unit.

Twenty-seven patients with positive fungal cultures, and 183 with bacterial infections were included in our analysis. Ten patients in the fungal cohort had bacterial co-infections. Of the bacterial cohort, 15 patients had 2 instances of separate infections within the same MILU stay. The last infection prior to discharge or death was utilized for analysis in these cases.

There were no differences in baseline demographics of age, race, or sex between the 2 cohorts (Table 1). Both cohorts also had similar Charlson Comorbidity Scores. The fungal and bacterial cohorts had similar proportions of patients admitted with cirrhosis, alcohol associated hepatitis, acute liver failure and severe acute liver injury. Viral hepatitis due to hepatitis B and C infection was more commonly the etiology of liver disease among patients with fungal infections, but other etiologies were similar between cohorts. Patients with fungal infections had higher rates of hepatorenal syndrome. One case of alcohol-associated hepatitis occurred without underlying cirrhosis in the bacterial cohort, while all other cases occurred with comorbid cirrhosis.

Table 1 Baseline cohort characteristics between liver intensive care unit patients with fungal and bacterial infections

Among the fungal cohort, 33% of patients also suffered surgical illnesses including small bowel obstruction, cholecystitis, colitis and abdominal fistula, during their ICU stay. Of those with isolated fungal infection, 71% received 5 d of antibiotic therapy prior to initiation of antifungal treatment.

Infection types and epidemiology

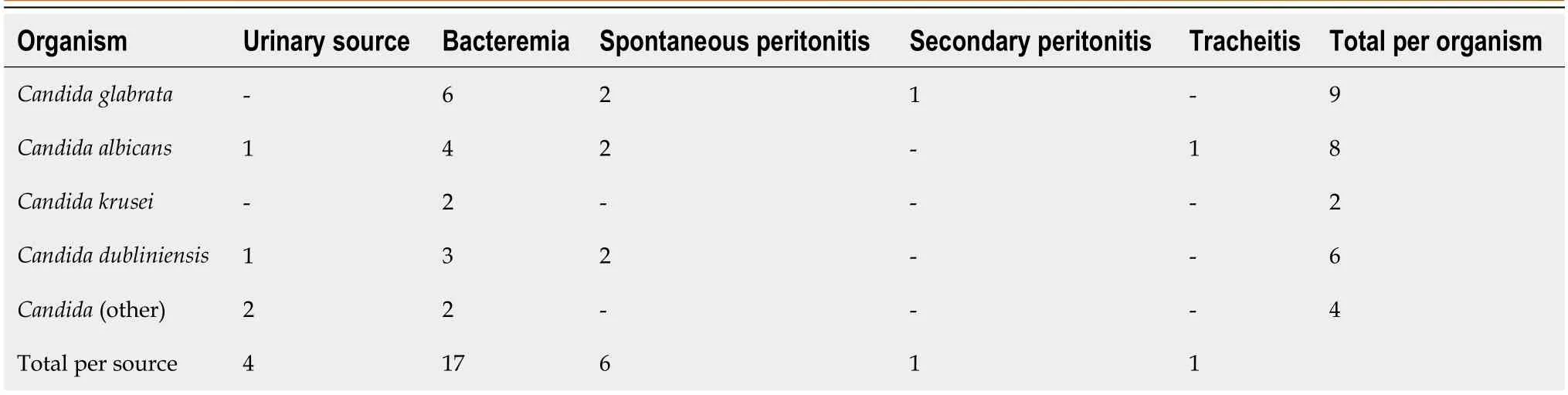

All isolated fungal infections wereCandidainfections (Table 2).Candida glabratawas the most common isolated fungus, followed byCandida albicans. Isolates were most frequently from blood, followed by ascites and urine. We isolated one case of secondary peritonitis and one case of tracheitis.

Table 2 Epidemiology of Candida isolates among patients with fungal patients in the intensive care unit

Among 183 patients with bacterial infections, 45 (24.5%) had co-infections with multiple bacterial isolates and 15 (8.1%) patients had 2 separate instances of bacterial infection during their MILU stay. Blood was the most frequently isolated source (Appendix). Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and respiratory and urinary tract infections were the most common sources of gram-positive infections following bacteremia. There were 117 g-positive cultures, of which the most common organism wasEnterococcus faecium, followed by methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus. There were 126 g-negative isolates, and the majority were caused byEscherichia coli, followed byKlebsiellaspecies.

Mortality, intensive care resource utilization, and transplant outcomes

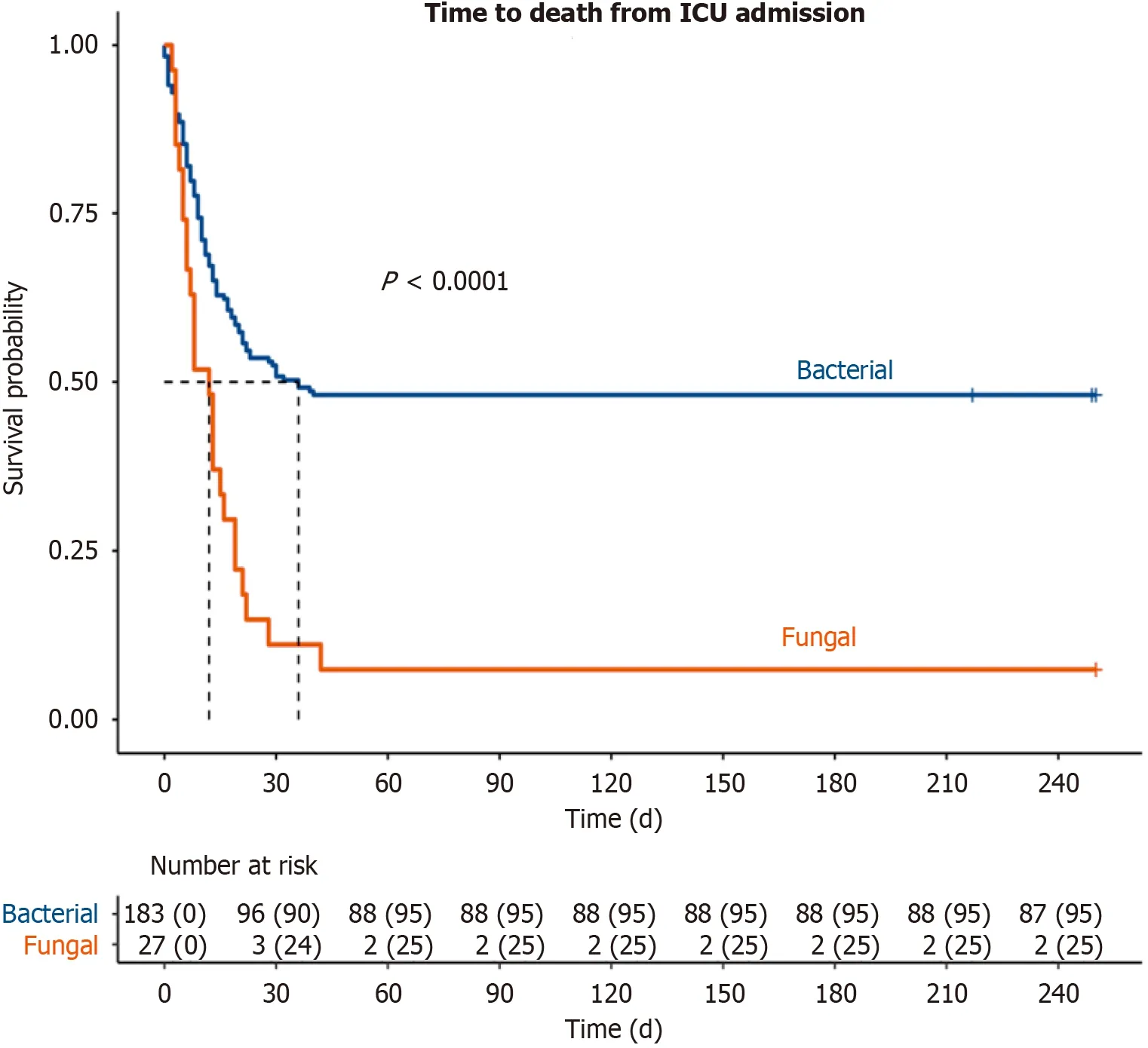

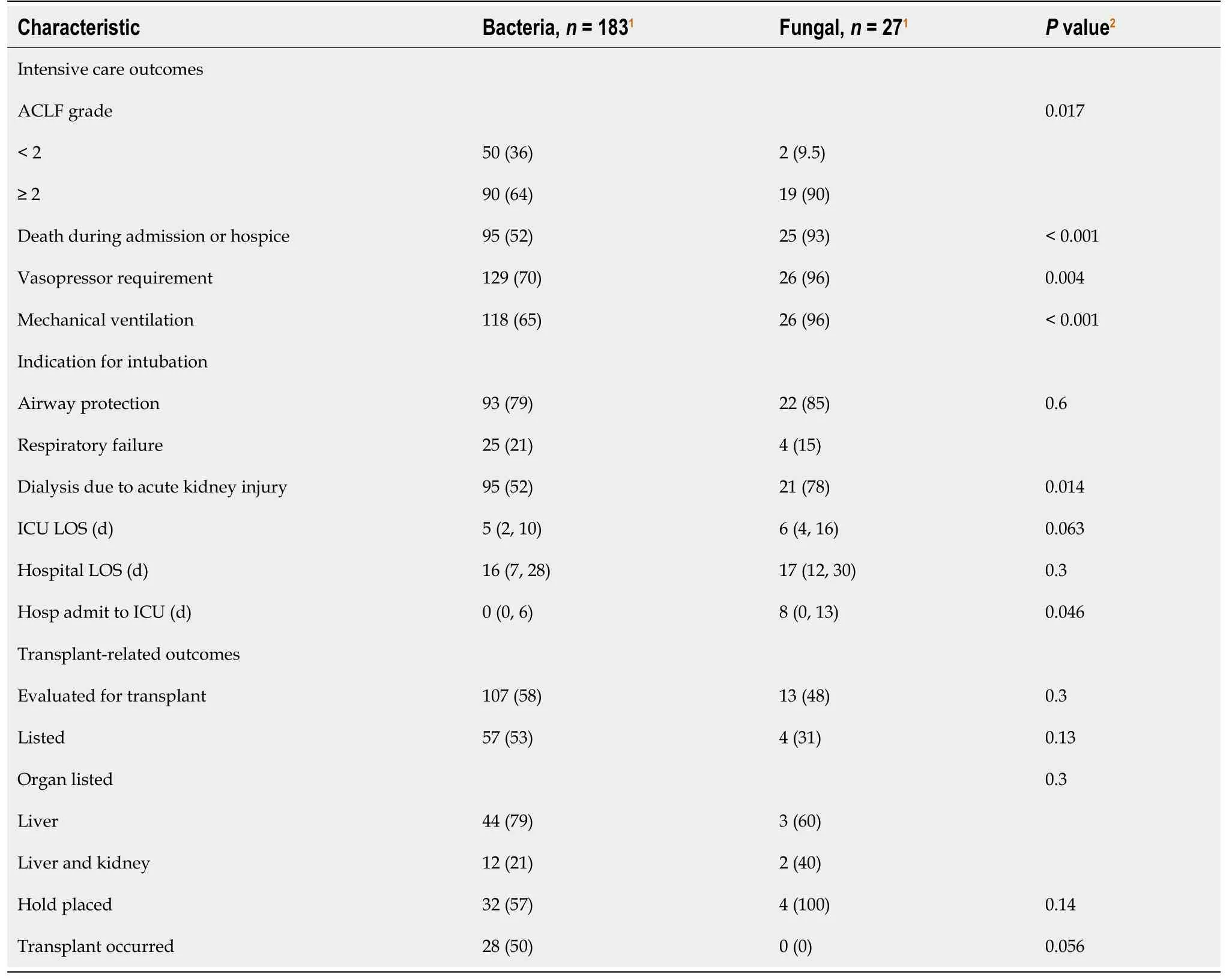

The mortality rate among patients with fungal infections was significantly higher than those with bacterial infections (93%vs52%,P< 0.001, Figure 2). Median survival among the fungal cohort was 12 d relative to 31 d in the bacterial cohort (Figure 2). The majority of patients with fungal infections had severe ACLF, defined as ACLF grade 2 or higher (90%vs64%,P= 0.02, Table 3), and either died or transitioned to hospice during their MILU stay (93%vs52%,P< 0.0001). One patient with fungal infection had decompensated cirrhosis without ACLF, while 34 patients in the bacterial cohort had decompensated cirrhosis alone. Significantly higher proportions of those in the fungal cohort required vasopressor support (96%vs70%,P= 0.04), mechanical ventilation (96%vs65%,P< 0.001), and dialysis initiation due to acute kidney injury (78%vs52%,P= 0.014). There were no differences in indication for intubation, MILU length of stay (LOS) or overall hospital LOS. However, those in the fungal cohort had longer hospital LOS prior to MILU admission (8 dvs0 d,P= 0.046).

Figure 2 Comparison of survival from intensive care unit admission between fungal and bacterial cohorts. ICU: Intensive care unit.

Table 3 Transplant and intensive care outcomes comparison between fungal and bacterial cohorts

There were no differences between fungal and bacterial cohorts in rate of transplant evaluation initiation (48%vs58%,P= 0.3) or rate of listing (31%vs51%,P= 0.13). Of those patients who were listed, all patients with fungal infection were subsequently placed on hold, and no patients with fungal infections received a transplant. Patients with fungal infection had higher rate of hold placement (100%vs57%,P= 0.14), and lower rates of transplant compared to bacterial counterparts (0%vs50%, 0 = 0.056); however, these differences did not achieve statistical significance.

Characteristics of acute infection and predisposing variables

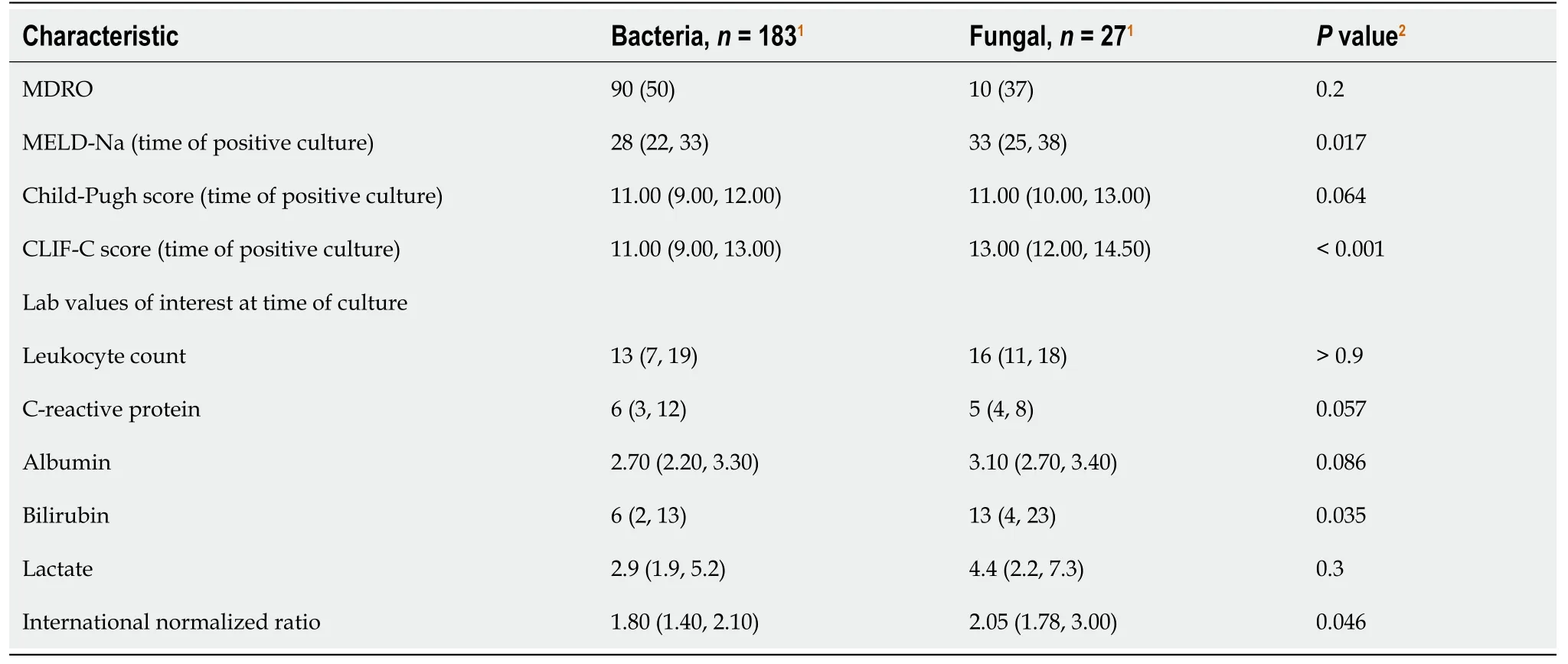

At the time of positive culture, fungal and bacterial cohorts had similar rates of infection with MDROs (37%vs50%,P= 0.2) and Child-Pugh scores (11vs11,P= 0.064) (Table 4). Patients in the fungal cohort had higher Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium (MELD-Na) (33vs28,P= 0.017) and CLIF scores (13vs11,P< 0.001). Albumin, lactate, leukocyte count, and C-reactive protein were not significantly different between cohorts.

Table 4 Comparison of infection characteristics among liver patients in intensive care unit between fungal and bacterial cohorts

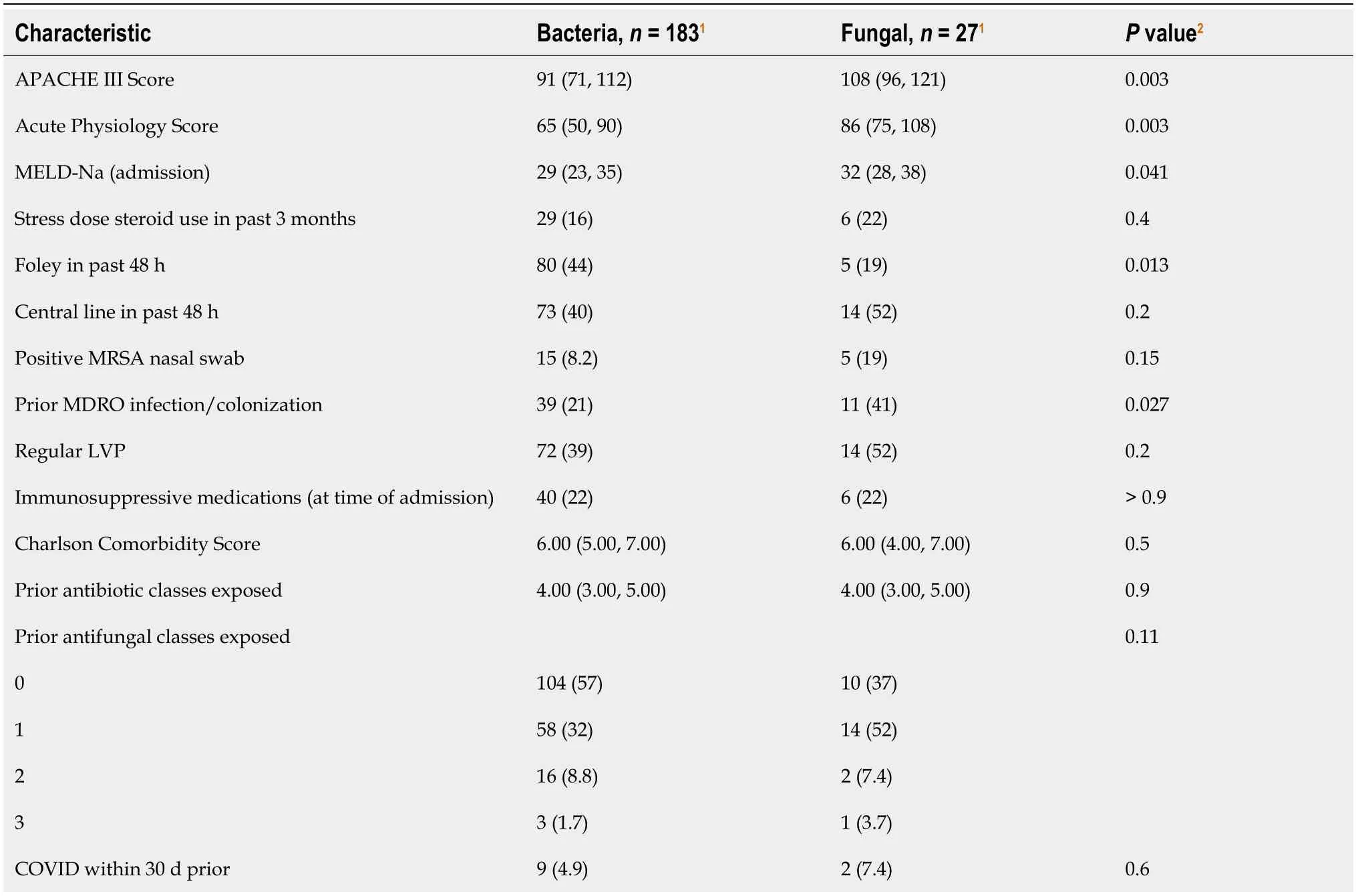

At the time of MILU admission, patients with fungal infection had significantly higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (108vs91,P= 0.003), Acute Physiology Score (86vs65,P= 0.003), and MELD-Na scores (86vs65,P= 0.041) (Table 5). There was no significant difference in the rate of central line use in 48 h preceding positive culture in fungal patients (52%vs40%,P= 0.2). Prior infection or colonization with MDRO was more common in the fungal cohort (41%vs21%,P= 0.027). Foley catheter use within 48 h preceding infection was less common among the fungal cohort relative to the bacterial cohort (19%vs44%,P= 0.013). There were no significant differences in preceding stress dose steroid use, screening MRSA nasal swab, regular large volume paracentesis requirement prior to admission (defined as at least monthly paracenteses within the preceding six months of admission), outpatient immunosuppression use, prior antibiotic exposure, prior antifungal exposure, or SARS-CoV-2 infection within preceding 30 d (Table 5).

Table 5 Comparison of pre-infection variables between liver patients in intensive care unit with fungal and bacterial cohorts

DlSCUSSlON

While bacterial infections have been recognized as a major cause of mortality among patients with advanced liver disease, especially as the most common trigger for ACLF, outcomes of fungal infections have not been as well studied. Our study is among the few to examine survival in this population and is among the first to compare outcomes of fungal and bacterial infections in the intensive care setting. Our findings demonstrate survival reductions are associated with fungal infections among patients with advanced liver disease who are receiving care in intensive care units such as the MILU. Further, our findings suggest the need for future work, such as exploration of predictors of poor outcomes to elucidate indications for palliative care, and implications for transplant.

The stark difference in mortality among fungal and bacterial cohorts is the most notable finding of our study. As bacterial infections are common and confer a 4-fold increase in mortality, several studies have examined factors associated with infection acquisition, outcomes, and prevention strategies[13,32-35]. Our findings highlight, comparative to bacterial infections that fungal infections are associated with worse survival, as 93% of patients in our fungal cohort died or transitioned to hospice care. This may be attributable in part to development of ACLF, as the majority of patients with fungal infections had severe ACLF relative to bacterial counterparts. It is clear from our results that fungal infection is likely associated with ACLF severity; however, we were unable to run predictive models given the respective aspect of our study design. Our findings affirm the need for future work to further elucidate associations, and the potential benefits of empiric or prophylactic fungal coverage.

Furthermore, patients with fungal infection had severely reduced rates of transplant. Half of listed patients with bacterial infections received liver transplantation, whereas no patients with fungal infections received liver transplantation. Other studies have shown that in ACLF grades 2-3, non-transplant 90-d mortality ranged from 52.3-79.1%[30]. Transplant is the only ultimate standard therapy for severe ACLF that does not rely on liver regeneration for clinical improvement; 1-year post-transplant survival has been shown to be over 80% regardless of ACLF grade, and is better among transplant recipients compared to non-recipients[36,37]. However, patient selection is crucial given the narrow window for transplant[38,39]. Several studies have examined pre-transplant predictors to prognosticate post-transplant survival in ACLF[39,40]. Certain factors associated with poor post-transplant prognosis, including age > 53 years and mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure, were seen among the majority of our fungal cohort. Serum INR has also been shown to be predictive of short-term post-transplant mortality, and was significantly elevated among the fungal cohort relative to bacterial counterparts[41]. Post-transplant, fungal infection has been found to be the second most common cause of mortality and significantly more common among patients with pre-transplant ACLF[42]. The role of fungal infection as a peri-transplant prognostic factor and whether positive fungal culture is a true contraindication to transplant remains to be seen.

While prior studies have reported relatively lower rates of fungal infection, our study found prevalence of fungal infection among all culture-positive patients in the ICU to be 12.9%, or 10.9% when including only sterile source isolates. This is higher than previously postulated estimates ranging between 2%-7% among hospitalized patients with cirrhosis[15,43], suggesting that fungal infection may be more common specifically in the intensive care setting. The incidence of invasive candidiasis in non-selected patients in the ICU has been reported to be between 1%-2%, and on the rise[44]. Our estimation of prevalence may be subject to bias, however, due to the limited size of our fungal cohort. Nevertheless, underestimation of prevalence of invasive fungal infections has been suggested in the past due to dependence of prior estimates on performance of specific fungal cultures. To enable early recognition, interest in non-culture based diagnostic tools is growing, though current clinical use remains limited[45]. Additionally, similar to our findings,Candidainfection has been associated with prolonged antibiotic administration prior to diagnosis ofCandidemia[46], potentially leading to under-diagnosis. Further epidemiologic characterizations of patients with advanced liver disease is thus crucial, as inadequate antimicrobial coverage is associated with increased mortality[15,34]. Our findings demonstrate this, asCandida glabratawas the most commonly isolated species, in keeping with recent trends towards the rising prevalence of non-albicansspecies[44]. While echinocandins have been recommended by the Infectious Disease Society of America for empiric antifungal therapy[47], recommendations differ forC. glabratadepending on susceptibility due to resistance.

In addition to empiric therapy, the severe mortality associated with fungal infections raises the importance of early risk stratification for potential prophylactic therapy. Markers of utility may be MELD-Na or ACLF grade cutoffs; MELD-Na has previously been shown to be predictive of fungal infection development[48]. In our study, MELD-Na was higher both at MILU admission and at time of infection among the fungal cohort. A prior study has also raised the possibility of prophylaxis in waitlisted patients with severe ACLF[49]. Our findings on pre-infection variables of interest may represent useful targets of future work to identify appropriate indications for prophylactic antifungals. In our cohort, fungal infections were associated with a higher rate of prior multi-drug resistant colonization and infection. Prior bacterial infection has been established as a risk factor for subsequent fungal infection development[19,43,50], and may represent an important indication to explore for prophylactic antifungal therapy in critically-ill liver patients. Additionally, bilirubin and INR were significantly higher among patients with fungal infections, though this may represent collinearity with the MELD-Na score. Further studies investigating these markers for independent inclusion in predictive models would be valuable. A prolonged hospital stay prior to ICU admission in the fungal cohort compared to the bacterial cohort may also suggest an increased rate of nosocomial infections in this population. Invasive fungal infections have been reported as important causes of healthcare-acquired infections, and may warrant further study in this setting[46].

Parallel to the need for early aggressive treatment among patients with fungal infections is also the need to develop prognostication tools to guide goals of care. The concepts of futility and palliative care in severe ACLF are rising due to the associated reductions in quality of life beyond that associated with decompensated cirrhosis alone. In our study, despite their poor survival, the fungal cohort had similar lengths of stay in the intensive care unit compared to bacterial counterparts, with higher rates of vasopressor support, mechanical intubation, and dialysis initiation. Furthermore, prior work has shown that survival withCandidainfection despite timely administration of antifungals is poor[51]. Our findings suggest the importance of exploring the potential prognostic role of positive fungal culture in severe ACLF, to better inform advanced care planning, improve end of life quality, and reduce psychosocial patient and family burden.

Several factors set our study apart from others. We provide data from a large population of unique MILU patients and used data from a prospectively maintained database over the course of four years. Within the unit, all patients are daily co-managed by hepatologists and intensivists, ensuring multi-disciplinary comprehensive care. We report on a critically ill, unique population of patients with complex pathologies seeking care at a quaternary center. We are also one of few studies to provide granular data on fungal infections in the critical care setting, and to comment on interplay with ACLF. An important limitation of some prior studies has been the use of population-based databases[37].

With these strengths, our study had some notable limitations. Despite data extracted from a prospective registry, our population had a limited sample size, and for this reason our study was limited in its ability to construct predictive models. Though being a quaternary referral center provides complexity and allows study of a critically ill population, data on patients’ pre-care from prior hospital admissions is at times unavailable; this may have impacted our comparison of pre-infection variables. Finally, due to our requirement for culture positivity, our study did not include patients who may otherwise meet criteria for infection despite lack of microbiological isolation. Selection by culture may allow bias towards selection of a population with higher illness severity; however, our study aimed to investigate infections in this cohort of critically ill patients, and culture positivity is crucial for differentiating infection from other acute states of decompensation/inflammation.

CONCLUSlON

Our findings demonstrate that fungal infection is associated with severe ACLF and marked increase in mortality among critically ill patients with advanced liver disease. We highlight the poor outcomes in this population despite aggressive supportive care and efforts towards stabilization for transplant evaluation. Future multi-center prospective studies are necessary to predict infection and prognosticate trajectory of care.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research background

Advanced liver disease predisposes critically ill patients to the development of fungal infections. While bacterial infections have been well-studied as the most common cause of acute-on-chronic liver failure and associated mortality, fungal infections have been relatively under-studied in the intensive care setting.

Research motivation

Infections increase mortality four-fold among critically ill liver patients, but few studies have compared predictors and outcomes of fungal infections to bacterial infections in this population.

Research objectives

We compared outcomes of fungal and bacterial infections among critically ill patients who were admitted to our unique medical intensive liver unit (MILU) from 2018-2022. We also conducted a comprehensive comparison of predictors and illness severity scores between these cohorts. Finally, we characterized microbiologic epidemiology of infections within our unit.

Research methods

Patients were identified for inclusion from a prospectively-curated database of all admissions to our MILU during the study period. Infections were defined based on culture positivity and clinical presentation. Data on outcomes and predictors of interest were collected manually through chart review.

Research results

We found that fungal infections among our patients were all caused byCandidaspecies and were most frequently blood isolates. Mortality was significantly worse among the fungal cohort relative to patients with bacterial infections, as the majority of these patients died or transitioned to hospice during the intensive care unit (ICU) stay. The majority of patients in the fungal cohort developed severe acute on chronic liver failure, and they had higher need for vasopressors, mechanical ventilation and acute kidney injury. Further, patients who developed fungal infections were sicker on admission to the unit. Patients with fungal infection had higher rate of transplant hold placement, and lower rates of transplant; however, differences did not achieve statistical significance.

Research conclusions

Fungal infection is a poor prognostic marker for patients with advanced liver disease in the critical care setting, and it is associated with significantly worse mortality than bacterial infection. This may be in large part due to development of severe acute on chronic liver failure. Patients who developed fungal infections had higher Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, and Acute Physiology Score scores on admission to the ICU.

Research perspectives

We believe our work highlights the importance of a need for future studies to investigate associations between fungal infections and acute on chronic liver failure. Furthermore, research efforts examining prognostic markers, potential indications for prophylactic/empiric antifungal use, and transplant outcomes would be equally important and informative for clinical practice.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:All authors were involved in study design; Khan S and Hong H collected data and designed the data collection tool; Khan S, Wang X, Wang Y, Sims O and Lindenmeyer CC were responsible for statistical analysis; Khan S, Bass S, Sims O, Koval C, Kapoor A and Lindenmeyer CC were involved in analysis and interpretation of results of statistical testing; Khan S, Sims O and Lindenmeyer CC were involved in writing the manuscript; all authors were involved in manuscript appraisal and approval.

lnstitutional review board statement:The study was reviewed and approved by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation Institutional Review Board [IRB# 22-721].

lnformed consent statement:Our Institutional Review Board allowed our study to proceed without the need for informed consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement:None of the study authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data sharing statement:Our statistical code and de-identified data may be made available upon reasonable request.

STROBE statement:The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:United States

ORClD number:Sarah Khan 0000-0002-4830-9176; Hanna Hong 0000-0001-6637-8573; Stephanie Bass 0000-0001-5175-0459; Yifan Wang 0000-0002-4663-6202; Xiao-Feng Wang 0000-0001-8212-6931; Omar T Sims 0000-0002-3207-2231; Christine E Koval 0000-0002-8196-2601; Aanchal Kapoor 0000-0001-5130-2373; Christina C Lindenmeyer 0000-0002-9233-6980.

S-Editor:Gong ZM

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Zheng XM

World Journal of Hepatology2024年3期

World Journal of Hepatology2024年3期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Update in lean metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

- Retrospective study of the incidence, risk factors, treatment outcomes of bacterial infections at uncommon sites in cirrhotic patients

- Palliative long-term abdominal drains vs large volume paracenteses for the management of refractory ascites in end-stage liver disease

- Comprehensive prognostic and immune analysis of sterol Oacyltransferase 1 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

- Prediction model for hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B with peginterferon-alfa treated based on a responseguided therapy strategy

- lnfluence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on response to antiviral treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B: A meta-analysis