The Wisdom Hidden in Yunjin Brocade

Yang Jiyuan

Yang Jiyuan is a researcher specializing in silk fabric technology and a national expert in the restoration of textile heritage. She is head of the Reproduction Department and director of Heritage Restoration at the Nanjing Yunjin Brocade Research Institute, and a city-level intangible cultural heritage inheritor in Nanjing.

Li Xiaowei

Li Xiaowei is an eighth-generation inheritor of the Pick-Flower Hall at the Jiangning Weaving House from the Qing Dynasty. She is a design expert at the Nanjing Yujin Brocade Research Institute, a senior artisan in Jiangsus arts and crafts, a senior rural revitalization technician, and a representative inheritor of Nanjings intangible cultural heritage.

Shi Kangni

An intermediate textile engineer. She joined the Nanjing Yujin Brocade Research Institute in 2019, working on Yunjin brocade craft processing, textile heritage restoration, and reproduction.

This book begins with the origin of silkworms, sequentially narrating the uniquely beautiful patterns of Yunjin brocade, the lesser-known but essential design concepts, the ancient wisdom encapsulated in the pick-flower knotting technique, the ingeniously crafted looms, and the numerous exquisite garments made from Yunjin brocade, including pieces that merge modern aesthetics with traditional brocade.

Chronologically, Shu Brocade is the earliest known. A specialty of Chengdu, Sichuan Province, Shu Brocade refers to the distinctive brocades produced in Shu County (now Chengdu, Sichuan) from the Han Dynasty to the Three Kingdoms Period. Shu Brocade, typically woven from dyed mature silk threads, features warp thread patterns, striped or dyed designs, and a combination of geometric patterns and decorations, with a history spanning over 2,000 years. “Shu” is the ancient name for Sichuan, renowned for its abundance of mulberry trees and silkworms, establishing it as a prominent center for sericulture in ancient times. Here, the sericulture industry originated earliest, making it one of the birthplaces of Chinese silk culture. Shu Brocade dates back to the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, flourishing during the Han and Tang dynasties, named after its production in the state of Shu. It has a long history and profound influence on traditional silk brocade production. In 316 BCE, following the Qin conquest of Shu, “Jin Guan City” was established south of the Yiliqiao Bridge in Chengdu. “Jin Guan” officials were appointed to supervise the production of brocade and embroidery, and this tradition continued into the Han Dynasty.

“Every brocade pattern having a meaning” is an artistic characteristic of Shu Brocade, representing visions and blessings for life. The weaving technique is exquisite and rigorous, and the color scheme is elegant and gorgeous, mostly using warp-colored yarns to create patterns, adding flowers with colored stripes, creating patterns with both warp and weft, adding brocade groups after colored stripes, adding flowers with square, rectangular, and geometric frames, creating symmetrical and continuous patterns, with bright and contrasting colors, and a unique style.

The Origin of Song Brocade

At the end of the Jin Dynasty, the “Upheaval of the Five Barbarians” led to the southward migration of the Han people. Shan Qianzhi, the prefect of Song in the Southern Dynasties, introduced brocade craftsmen from Shu (Sichuan) and established the Douchang Jinshu (Douchang Brocade Office), the official weaving institution of the Eastern Jin and Southern Dynasties in Danyang (Jiangsu), which was adjacent to Nanjing, the capital of Liu Song, (Douchang Brocade Office, this is the name of the earliest documented official weaving institution in the south of the Yangtze River, which is why we say Yunjin originated in 417 CE), bringing Shu brocade skills to the south of the Yangtze River and developing Song brocade based on Shu brocade. Mainly produced in Suzhou, it was also referred to as “Suzhou Song Brocade.” Song Brocade, known for its vibrant colors, exquisite patterns, and sturdy yet soft texture, was once hailed as the “crown of Chinese brocades,” with products including heavy brocades, fine brocades (collectively known as “large brocades”), as well as box brocades and small brocades. Heavy brocades are thick and mainly used for palace and hall decorations; fine brocades, the most representative of Song Brocades, are of medium thickness and are widely used for clothing and mounting. During the Five Dynasties Period, King Qian Liu of Wuyue established a handicraft workshop in Hangzhou, gathering over 300 skilled brocade weavers. In the early Northern Song Dynasty, the capital, Bianjing, established the “Lingjin Academy,” assembling over 400 looms and bringing in many highly skilled Shu Brocade weavers from Sichuan as the core team. Additionally, a “Transport Commissioners Brocade Academy” was set up in Chengdu. After the Southern Song Dynasty imperial court moved to Hangzhou, a Song Brocade weaving bureau was established in Suzhou. Shu Brocade weavers and machines from Chengdu were relocated to Suzhou, gradually shifting the silk industrys center to the south.

During the Song Dynasty, weaving bureaus or departments were set up in Suzhou, Hangzhou, Jiangning (Nanjing), and other places. In the Song era, the silk industry in the Jiangnan region reached its peak, and Suzhou saw the emergence of a very fine and thin new variety of brocade, ideal for mounting books and paintings. Examining the brocade-mounted scrolls from the Song Dynasty reveals the existence of over 40 varieties of Song Brocade, including “Brothel Terrace Brocade,” “Embroidered Brocade,” and “Purple Hundred-Flower Dragon Brocade.” Initially, Suzhou Song Brocade was exclusively used for mounting books and paintings. Traditional Song Brocade production involved many steps. Its basic characteristic is the use of a combined warp and weft thread structure to display patterns, employing unique color throwing and changing techniques, enriching the fabrics surface colors and textures. Artistically, it features varying geometric frames filled with natural flowers, auspicious patterns, and harmonious, contrasting colors, creating a vibrant yet elegant and sophisticated style. Thus, since the Song Dynasty, Song Brocade replaced the warp brocades of the Qin and Han periods and the weft brocades of the Sui and Tang periods, flourishing through the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. This craft was absorbed by Yunjin Brocade and has continued to influence contemporary brocade weaving techniques.

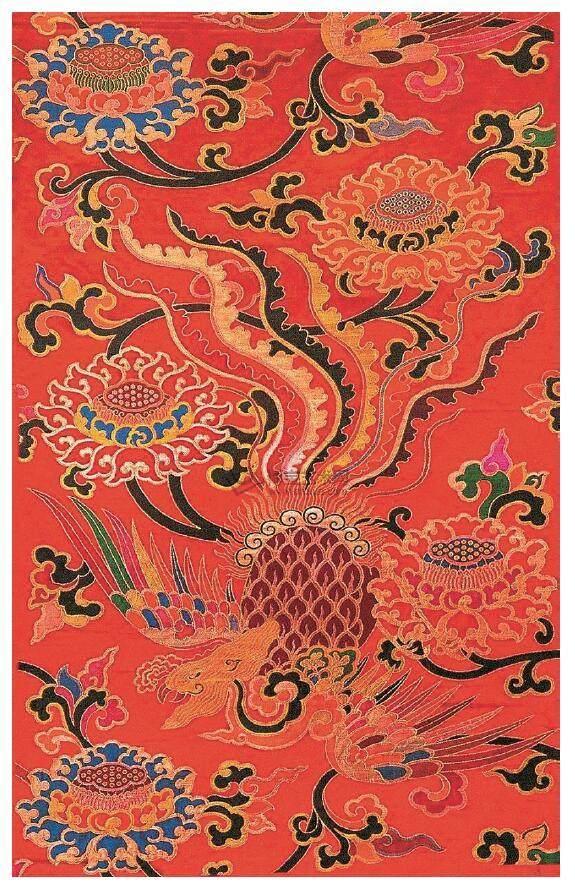

It is evident that Chinas three renowned brocades, Shu, Song, and Yunjin, represent the developmental stages of brocade, evolving from the pinnacle of silk weaving techniques post-Han Dynasty. Yunjin Brocade, as the foremost among the three, incorporates the finest patterns from all dynasties. Craft-wise, it integrates all previous techniques and develops its own unique characteristics based on the latest technology. In terms of looms, it encompasses the best features from looms of each era, culminating in the large-patterned wooden loom that incorporates most functions of looms from previous generations. Yunjin Brocade can be described as a culmination of achievements, a beautiful name, intricate in craftsmanship, and laborious in process, thus becoming a silk fabric exclusively used by the royal family.

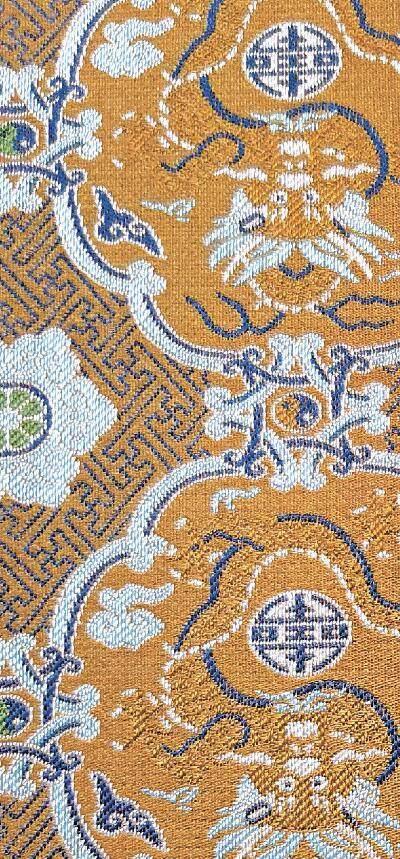

Yunjin Brocade can be defined as a fabric made with exquisite materials, fine craftsmanship, elegant and rich patterns, and colors, resembling the magnificent beauty of colorful clouds in the sky. Thus it was named for its luxurious and splendid appearance, akin to clouds and rosy dawn. Additionally, known as “Nanjing Yunjin Brocade,” it is exclusively produced in Nanjing. Its main features include flowers with varying colors, transverse warp, broken weft, and carved-out panel weaving. When viewed from different angles, the colors of the flowers on the same fabric appear different. Used for royal garment making, Yunjin Brocade, in its design and weaving, is meticulous, sparing no expense, and constantly striving for perfection. It was the exclusive fabric for royal garments like dragon robes and imperial attire during the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties (e.g., gold-thread peacock feather embroidered gauze dragon robes and satin dragon robes, green gold-thread embroidered long-sleeve over-the-shoulder satin collared jackets for women, etc.), reserved for court use or as rewards for meritorious officials (like the Ming Dynastys gold-thread embroidered dragon silk skirts). Later, it expanded to the clothing of officials, scholars, and ladies of the elite class, as well as festive and wedding attire for the general public.

Named for its brilliant and dazzling colors, like clouds in the sky, Yunjin Brocade evolved from the excellent traditions of past brocades, amalgamating various silk weaving experiences to reach the pinnacle of silk craftsmanship, hailed as the “crown of brocades,” representing the highest achievement in Chinese silk artistry, encapsulating the essence of Chinese silk weaving skills, a glittering jewel of Chinese silk culture.

There are intricate connections between the various brocades of each dynasty. Without the Shu Brocade of the Han Dynasty or the kesi (cut silk) and carved weaving techniques of the Song Dynasty, there would be no Yunjin Brocade varieties with warp-reversing and flower-embellishing styles. Without the extensive use of gold threads, the development of Yunjin Brocades with golden treasure grounds and gold-thread brocades during Ming and Qing dynasties would be challenging. Without the colored brocades of the Song Dynasty, the emergence of colorful flowered treasury brocades would be unlikely. Without Shu Brocades warp brocade looms and small-patterned wooden looms, there would be no large-patterned looms for Yunjin Brocade, making it impossible to weave multicolored, large-patterned, individually patterned Yunjin fabric pieces.

Named for its brilliant and dazzling colors, like clouds in the sky, Yunjin Brocade evolved from the excellent traditions of past brocades, amalgamating various silk weaving experiences to reach the pinnacle of silk craftsmanship. Hailed as the “crown of brocades,” it represents the highest achievement in Chinese silk artistry, encapsulating the essence of Chinese silk weaving skills, a glittering jewel of Chinese silk culture.

The Wisdom Hidden in Yunjin Brocade

Yang Jiyuan, Li Xiaowei, Shi Kangni

Jiangsu Phoenix Fine Arts Publishing House

November 2023

128.00 (CNY)

- 中国新书(英文版)的其它文章

- Wen Zhengming: A Suzhou Elegance Legend

- The Legend of the City

- Candlelight Tales in the Whitewashed Hall

- Jiangnan Medical Sage Yu Jiayan

- The China Path -- A Unique Modernization Journey (English Edition) Published and Distributed

- 2023 China Shanghai International Children’s Book Fair Concludes