The Legend of the City

Zhou Wenhan

Zhou Wenhan is an art and architecture critic and writer. He worked as a cultural reporter for the China Financial Times and Beijing News and later traveled to India, Spain, Southeast Asia, and other places for cultural exploration.

“People cannot live without their destined age,” Wang Shizhen lamented in his biography of Wen Zhengming, Wen Zhengming: The Esteemed Masters Biography. The people of Wu admired Xu Zhenqings poetry, Zhu Yunmings calligraphy, and Tang Bohus painting. These people were proficient in one art each and were friends with Wen Zhengming, but unfortunately, they passed away one after another and did not live as long as Wen Zhengming. In addition, Wen Zhengming was good at painting, calligraphy, poetry, and prose, eventually becoming the “Mr. Wen” everyone in Suzhou knew.

In the 32 years after Wen Zhengming returned from Beijing, he remained Suzhous most famous painter and connoisseur. Wang Shizhen described exaggeratedly, “All kinds of people came to visit, and the shoes outside were piled up, but the gentleman only received students, sons or relatives of old friends and those who were in trouble because of marriage. Even if they insisted, the gentleman would accompany them patiently. Others, such as the officials of the counties and states, or those with carriages and horses, or rich merchants and traders, brought precious gifts and filled the outside of the door, but they could not catch a glimpse of the gentleman. And then those who wanted to ask the gentleman for something but could not get it, they would go find those students, sons, or relatives of old friends and pay them a high price for what they got from the gentleman. Therefore the gentlemans paintings and calligraphy were spread all over the world, and often the originals were not as good as one-twelfth of the fakes. The people who lived around Wu were blessed by the gentleman for decades.”

After Wen Zhengming resigned from the Imperial Academy in Beijing and returned to Suzhou, he became a cultural idol in the city of Suzhou. This was true both officially and among the common people. In the early years of the Jiajing reign, when the women of Suzhou city prayed for sons, they would worship a goddess called “Grandma,” and when they offered wine and bowed, they would say, “Tonight I offer Grandma three cups of wine, and wish that my family would raise sons like Lu Nan, Wang Huan, and Wen Zhengming.” Lu Nan and Wang Huan were famous talents in Suzhou city at the end of the Hongzhi reign and the beginning of the Jiajing reign, but unfortunately, they did not pass the imperial examination for many years and only served as small officials with the status of scholars. No one remembered their names by the Wanli reign, but Wen Zhengming had a lasting reputation.

In his daily life, Wen Zhengming had breakfast every day, and ate some snacks like “Bing Er” in the morning. He would drink yellow wine when he ate lunch. He was used to drinking two cups of wine as soon as he sat down, then eating, and after the guests had drunk a few rounds, he would drink another two cups, which meant that his lunch habit was to drink two cups of wine after a break for eating. He ate “mianfan” (probably noodles) in the afternoon (from three to five oclock) and two bowls of porridge when he lit the lamp at night.

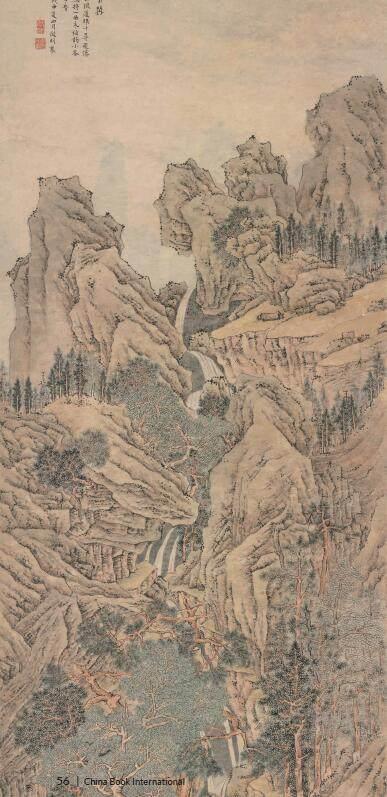

Besides writing, painting, and entertaining guests with conversation, Wen Zhengmings favorite thing was to appreciate and comment on paintings and calligraphy. When friendly collectors like He Liangjun brought paintings and calligraphy to visit Wen Zhengming, he would open each piece one by one and admire them until evening. He also liked to take out his own collection and share it with fellow enthusiasts. He often went into his study and brought out four volumes of paintings and calligraphy, and after opening and looking at them, he went back into the study and brought out another four volumes for people to see. He never got tired of doing this repeatedly. Wen Zhengming liked to listen to children singing opera and artists telling stories.

He also handwrote an article by Wei Liangfu, the founder of Kunqu opera, called Standardization of Southern Operatic Lyrics, which shows his interest in opera.

In the seventeenth year of the Jiajing reign (1538), when the imperial censor Wen Renquan returned to Beijing after inspecting Suzhou and Songjiang, he ordered the building of an archway named “Chong De” for Zhu Xizhou and an archway named “Biao Jie” for Wen Zhengming, to commend their moral integrity. When Wen Zhengming, who was 69 years old, heard the news, he wrote a letter to let his son submit it to the prefect of Suzhou, Wang Yi, to express his gratitude. He modestly said that he was “the lowest in rank, character, ability and intelligence” and did not deserve such an extraordinary commendation and could only make the scholars laugh. However, the government did not listen to Wen Zhengmings opinion and still built the “Biao Jie” archway west of Deqing Bridge. Before that, there was already an archway in the street where the Wen family lived, which commended Wen Lin and Wen Sen for passing the imperial examination called “Brothers Lian Fang.” There was also an archway in the city of Suzhou that commended Wen Hong, Wen Lin, and Wen Sen, called “Father and Son Ji Mei.” Now, there was Wen Zhengmings archway, further highlighting the Wen familys status in Suzhou.

In the twenty-eighth year of the Jiajing reign (1549), when Wen Zhengming was 80 years old, the prefect of Suzhou, the magistrate of Changzhou, and the scholars and gentry in the city all congratulated him with paintings and calligraphy. Lu Can wrote The Imperial Scholar Wen Zhengming: An Account of His 80th Birthday Celebration, and Zhu Xizhou, Xie Shichen, and 13 others collaborated on the Celebratory Album of Poems and Paintings for the Esteemed Wen Zhengmings 80th Birthday, in which Xie Shichen painted “Heng Shan,” “Lou Jiang” and “Bao Dai Qiao” in three sections, Lu Zhi painted “Fen Xi” and “Yang Cheng Hu” in two sections, and Qian Gu, Zhu Lang, and Chen Kui respectively painted “Dong Chan Si,” “Qi Men” and “He Hua Dang.” The places painted were all related to Wen Zhengmings life, and Mao Xigu, Yuan Bu, and Huangfu Chong each wrote poems on the opposite pages. Another ten disciples of Wen and famous people in Wu also collaborated on the “Compendium for the Eightieth Birthday Celebration” to congratulate him. The first was Peng Nians small script “Shou Xu”, the painters included Xie Shichen, Lu Zhi, Qian Gu, Zhu Lang, and Chen Kui, and the poets included Yuan Bi, Yuan Bu, Xu Chu, Huangfu Chong, Mao Xigu, among others. It can be seen that at that time, Wen Zhengmings disciples and friends had discussed and prepared in advance to congratulate Wen Zhengming and determined the content and arrangement of the poems and paintings, and cooperated to complete two albums. In addition, friends such as Liu Lin, Gu Menggui and others wrote birthday poems, and He Liangjun also wrote three long poems to congratulate him. In order to thank the relatives and friends who came from afar to celebrate his birthday, Wen Zhengming gave each of them a copy of his small script, One Thousand Character Primer.

Wen Zhengming also appeared in a series of cultural projects organized by local officials. For example, in the fifteenth year of the Jiajing reign (1536), following the rebuilding of the Changzhou county school, the magistrate requested Wen Zhengming to write the Records of the Reconstruction of Confucian Learning in Changzhou County. The steles inscription was engraved in seal script by Scholar Wang Guxiang. After such official cultural projects were completed, local celebrities were usually invited to write records. Inviting Wen Zhengming instead of Jinshi officials to write showed the degree of attention he received at that time. The imperial censor Wen Renquan supervised the education of Nanji, and ordered the county school to engrave the Tang Book when he inspected Suzhou. After it was completed in the eighteenth year of the Jiajing reign, he asked Wen Zhengming to write Reprinting the Old Tang Book. In the thirty-sixth year of the Jiajing reign (1557), Wen Zhengming, who was 88 years old, wrote Records of the Charitable Lands for the Suzhou Prefecture Schools by the prefect of Suzhou, Wen Jingkui, for the stele.

Other local officials also invited Wen Zhengming to write or write related articles, such as the Prefect of Shaoxing, who asked him to write the Record of the Restoration of the Orchid Pavilion in the twenty-eighth year of the Jiajing reign (1549). This was to commemorate the cultural event of Wang Xizhi and others elegant gatherings in the past. It was a perfect match to ask Wen Zhengming, a famous calligrapher, to write it. Wen Zhengmings influence even reached the northwest. In the first month of the thirty-fourth year of the Jiajing reign (1555), the deputy envoy of Taomin Road, Qi Fengxiang from Qingzhou, Shandong, saw that the local calligraphy style was indifferent and asked someone to engrave four poems handwritten by Wen Zhengming on stone and preserve them in the official residence, for the local literati to learn from.

Wen Zhengming: A Suzhou Elegance Legend

Zhou Wenhan

Tsinghua University Press

September 2020

99.00 (CNY)