From Paris to the Nine-Story Pavilion

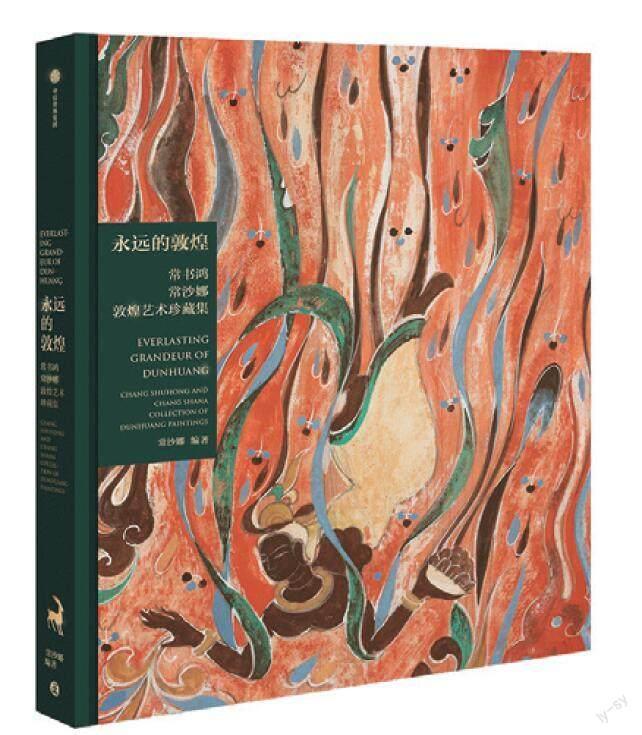

This book compiles the artistic creations of “Guardian of Dunhuang” Chang Shuhong and “Eternal Dunhuang Girl” Chang Shana, spanning over 80 years and various periods. Featuring diverse Dunhuang-related themes, it includes over a hundred pieces of Dunhuang mural restorations, copies, organization, and re-creations, some of which were previously unpublished. Chang Shana vividly interprets the characteristics of Dunhuang art, recalling the Dunhuang connection of two generations, and leads readers to experience the splendor of this artistic treasure.

Chang Shana

Chang Shana is a renowned educator and artist in art and design. Born in Lyon, France, in 1931, she later moved to Dunhuang with her parents and studied and copied Dunhuang murals under her father, Chang Shuhong. She taught at Tsinghua University and the Central Academy of Fine Arts and served as the dean of the Central Academy of Art and Design. She participated in the decoration of key national architectural design projects and mural creation. She is a recipient of the “Lifetime Achievement Award for Chinese Art” from the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles.

In the early 20th century, a group of Chinese painters, including my father, went to Paris to study Western painting. I was born in Paris. At that time, my home was a gathering place for art students who studied in France. Painters, sculptors, architects, and many Chinese students who visited Paris were our guests.

My father first came to France when he was 23. He originally went to study dyeing and weaving but later accidentally became well-known for his oil paintings. His oil paintings incorporated the national characteristics of Chinese painting, and his distinctive artistic style was recognized by Westerners. He won awards in Europe repeatedly. My father created The Painters Family with his family members as models and won a silver medal at the “Spring Salon” in Paris. He created Shanas Portrait for me, which was bought by the director of the Museum of Modern Art, Dou Shaluo, on behalf of France. It is now collected in the Guimet Museum in France. At that time, French art critics called him “the most important star of tomorrow” and predicted that as long as this Chinese student stayed and painted in Paris, the list of world art masters would have one more Chinese name.

However, an accidental encounter on the banks of the Seine in autumn of 1935 changed the course of my fathers life. That evening, my father was walking along the Seine, passing by a row of bookstalls specializing in art books, when a set of six booklets bound as The Dunhuang Grottoes Catalogue caught his attention. This set of albums showed more than 300 murals and statues, which were photographed by Pelliot from the Dunhuang Grottoes in Gansu, China, in 1907. My father was deeply attracted by the images in the book as if he had discovered a new world. The next morning, he went to Musée Guimet nearby, which exhibited Dunhuang relics, to see those great artistic creations with his own eyes. My father thought to himself: “I am a person who is fascinated with Western culture, and I used to be very proud of being a painter of Montparnasse, always mentioning Greece and Rome. Now, facing the countrys long and splendid cultural history, I feel guilty and forgetful of my ancestors. I am really ashamed and dont know how to repent!” My father decided to return to his motherland and go to Dunhuang to see for himself. (In 2018, I went to France to hold the “Flowers of Dunhuang” exhibition. The team took me to visit the residence of my childhood and the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine in Paris to recall the footsteps of my parents. To my surprise, the owners of the bookstalls were very interested in communicating with me, an old Chinese lady who could speak French. Many of the bookstall owners said they knew my father, Chang Shuhong, and his fate with Dunhuang. I was very happy. I didnt expect that after so many years, there are still people in Paris who remember my father and his story with Dunhuang!)

In 1936, my father accepted a professorship position at the Peiping Art College and went to Beijing alone. In 1937, my mother took me back to China in the fire of the Anti-Japanese War. Then, the family moved around in the war, living a life of displacement. But my father was the kind of person who had to realize his ideas. Dunhuang was always his dreamland.

In the autumn of 1942, Mr. Liang Sicheng asked my father if he would like to work at the proposed Dunhuang Art Institute. My father gladly accepted the position of deputy director of the preparatory committee. Although my mother disagreed, my father still resolutely decided to go to Dunhuang and decided to take the whole family with him. He had to do what he had decided.

Soon, the proposal to establish the National Dunhuang Art Institute was approved, and my father was officially appointed as the director. My father first set off from Chongqing, took an open truck to Lanzhou, and finally managed to recruit a team of people and horses. In the early spring of 1943, six people, wearing old sheepskin jackets and old felt hats, sat in an old open truck and headed west toward Dunhuang. It took them a month and four days to get from Lanzhou to Dunhuang. After arriving at Anxi (now Guazhou County, Jiuquan City, Gansu Province), the rest of the road could only be done by walking or camel. They hired more than a dozen camels and made their way through the desert, where there were only sparse camel thorns and grass, and finally arrived at the foot of Mingsha Mountain.

Facing the holy land in his dreams, facing the tall landmark building of the Nine-Story Tower, my father was shocked again: The beautiful Dunhuang art, under the ravages of time and sand, under the years of human destruction, had already decayed and was pitiful. My father wrote in his memoir: “The treasure has been plundered for three or four decades, and such a great art treasury still does not get the minimum protection and appreciation. When we first arrived here, there were cattle and sheep grazing in front of the caves, and the caves were used as places for gold diggers to stay overnight. The fallen murals were mixed in the ruins everywhere. I was overwhelmed with emotion, and the work that weighed on our shoulders would be so arduous and heavy!”

It was such a deep feeling that made my father root himself in Dunhuang and never leave.

Eternal Dunhuang

Edited and written by Chang Shana

CITIC Press Group

January 2024

238.00 (CNY)

- 中国新书(英文版)的其它文章

- Wen Zhengming: A Suzhou Elegance Legend

- The Legend of the City

- Candlelight Tales in the Whitewashed Hall

- Jiangnan Medical Sage Yu Jiayan

- The China Path -- A Unique Modernization Journey (English Edition) Published and Distributed

- 2023 China Shanghai International Children’s Book Fair Concludes