Effect of perioperative branched chain amino acids supplementation in liver cancer patients undergoing surgical intervention: A systematic review

Kwan Yi Yap,HongHui Chi,Sherryl Ng,Doris HL Ng,Vishal G Shelat

Abstract BACKGROUND Branched chain amino acid (BCAA) supplementation has been associated with favourable outcomes in liver malignancies requiring definitive resection or liver transplantation.Currently,there are no updated systematic reviews evaluating the efficacy of perioperative BCAA supplementation in patients undergoing surgery for liver cancer.AIM To evaluate the efficacy of perioperative BCAA supplementation in patients undergoing surgery for liver cancer.METHODS A systematic review of randomized control trials and observational studies was conducted on PubMed,Embase,Cochrane Library,Scopus,and Web of Science to evaluate the effect of perioperative BCAA supplementation compared to standard in-hospital diet,in liver cancer patients undergoing surgery.Clinical outcomes were extracted,and a meta-analysis was performed on relevant outcomes.RESULTS 16 studies including 1389 patients were included.Perioperative BCAA administration was associated with reduced postoperative infection [risk ratio (RR)=0.58 95% confidence intervals (CI): 0.39 to 0.84,P=0.005] and ascites [RR=0.57 (95%CI: 0.38 to 0.85),P=0.005].There was also a reduction in length of hospital stay (LOS) [weighted mean difference (WMD)=-3.03 d (95%CI: -5.49 to -0.57),P=0.02] and increase in body weight [WMD=1.98 kg (95%CI:0.35 to 3.61,P=0.02].No significant differences were found in mortality,cancer recurrence and overall survival.No significant safety concerns were identified.CONCLUSION Perioperative BCAA administration is efficacious in reducing postoperative infection,ascites,LOS,and increases body weight in liver cancer patients undergoing surgical resection.

Key Words: Branched-chain amino acid;Liver cancer;Liver surgery;Nutritional supplement;Perioperative supplementation

INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer is a global health issue with an estimated incidence of over 1 million cases by 2025[1].Secondary liver cancer is more prevalent than primary liver cancer[2-4].Lung and colorectal primaries account for half of the cases[5].Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for approximately 90 percent of all primary liver cancers[1],and is the third most common cause of cancer mortality in the world[6].Hepatectomy and liver transplant are the predominant curative treatments for liver cancers[7,8].

Although technological innovation and adoption of prehabilitation strategies have made hepatic surgery safe,there are still substantial morbidity risks,especially in cirrhotic patients[9].Emerging evidence suggests that levels of branched chain amino acids (BCAAs),namely valine (Val),leucine (Leu) and isoleucine (Ile),are decreased in various forms of hepatic injury[10].As important substrates for protein synthesis and regulators of protein turnover,BCAAs are involved in the pathophysiology of HCC by affecting gene expression,apoptosis,and regeneration of hepatocytes[10].Additionally,advanced liver diseases are usually associated with systemic catabolism and depletion of muscle mass[11].

In rat model studies,BCAAs have been reported to promote hepatocyte proliferation and suppress growth of HCC.Kimetal[12] reported that after major hepatectomy,supplementation with BCAAs helps not only to maintain a stable plasma BCAA/aromatic amino acids ratio,but also promotes liver regeneration in rats.BCAAs delay progression of carbon tetrachloride(CCl4)-induced chronic liver injury by attenuating hepatic apoptosis and stimulating the production of hepatocyte growth factors[13,14].Miumaetal[15] reported that all three BCAAs down-regulate vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression during HCC development.Through these mechanisms,supplementation with BCAA may potentially suppress HCC development and accelerate post-surgical recovery.Furthermore,many studies have reported that preoperative malnutrition increases the risks of postoperative morbidity and mortality[16-19].The benefits of administering BCAA to patients with HCC undergoing surgical treatment appear clear and promising.

Despite studies favouring BCAA supplementation,evidence of actual and measurable benefit is lacking.A 2012 Cochrane review showed that nutritional interventions for patients undergoing liver transplant did not offer benefits[20].Another review demonstrated that oral BCAA supplementation improved 3-year mortality in HCC patients,but without impact on cancer recurrence[21].In a meta-analysis on the use of supplemental BCAAs during the perioperative period in gastrointestinal cancer patients,Cogoetal[22] reported an improvement in morbidity from postoperative infection but no reduction in cancer recurrence.

Therefore,from current literature,it is unclear if the reported advantages of BCAA supplementation during surgical interventions in liver cancer warrant routine perioperative administration.Given these knowledge gaps,it is necessary to appraise the current evidence to determine if BCAA supplementation has beneficial impact on patients undergoing liver resection for various oncological indications.Thus,the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the role of perioperative BCAA supplementation in patients undergoing liver resection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[23].This review is part of a systematic review protocol registered on PROSPERO(CRD42022341658).Search of five databases (PubMed,Embase,Cochrane Library,Scopus,and Web of Science) was conducted on July 6,2022 for articles published since inception up to 6 July 2022.Keywords related to the terms (“BCAA”or “Branched-chain amino acid” or “Leu” or “Val” or “Ile” or “amino acid”),[(“liver” or “hepatic” or “hepatocellular”)and (“carcinoma” or “cancer” or “malignancy” or “tumour” or “neoplasm”)],(“resection” or “surgery” or “preoperative”or “perioperative” or “postoperative” or “hepatectomy” or “liver transplantation”) were used in literature search.The full search strategy is available in Supplementary Table 1.

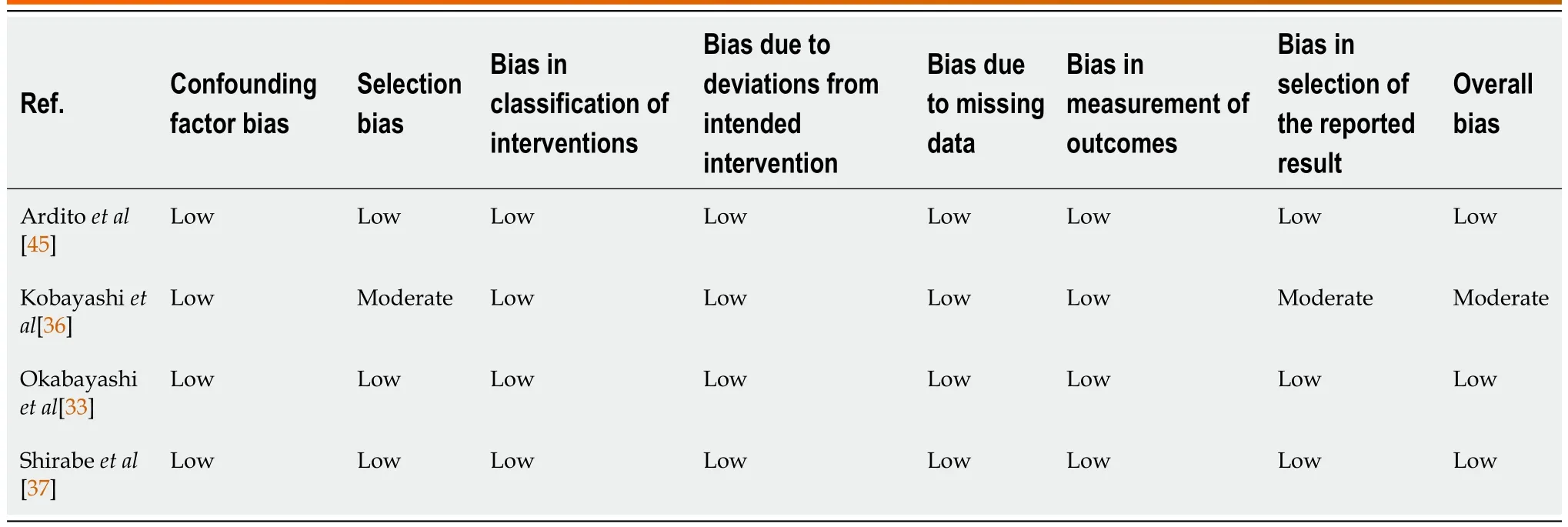

Table 1 Risk of bias assessment of non-randomised studies,using Cochrane ROBINS-1 tool

Study selection

Studies comparing outcomes of BCAAvsno supplementation in the perioperative period among liver cancer patients were considered for inclusion.Clinical trials and observational studies fulfilling the following criteria were included in the review: (1) Patients with a diagnosis of primary or secondary cancer in the liver;(2) patients underwent either hepatectomy or liver transplant;and (3) study has a control arm (placebo or normal usual diet).We excluded studies with patients undergoing liver surgery for other indications,or undergoing treatment procedures for liver cancer,such as radiofrequency ablation or transarterial chemoembolisation,without surgical intervention.All other studies were included,and details of source databases used in each included study were collected.The details of inclusion and exclusion criteria of this review according to the Population,Intervention,Comparison,Outcomes and Study framework are documented in Supplementary Table 2.

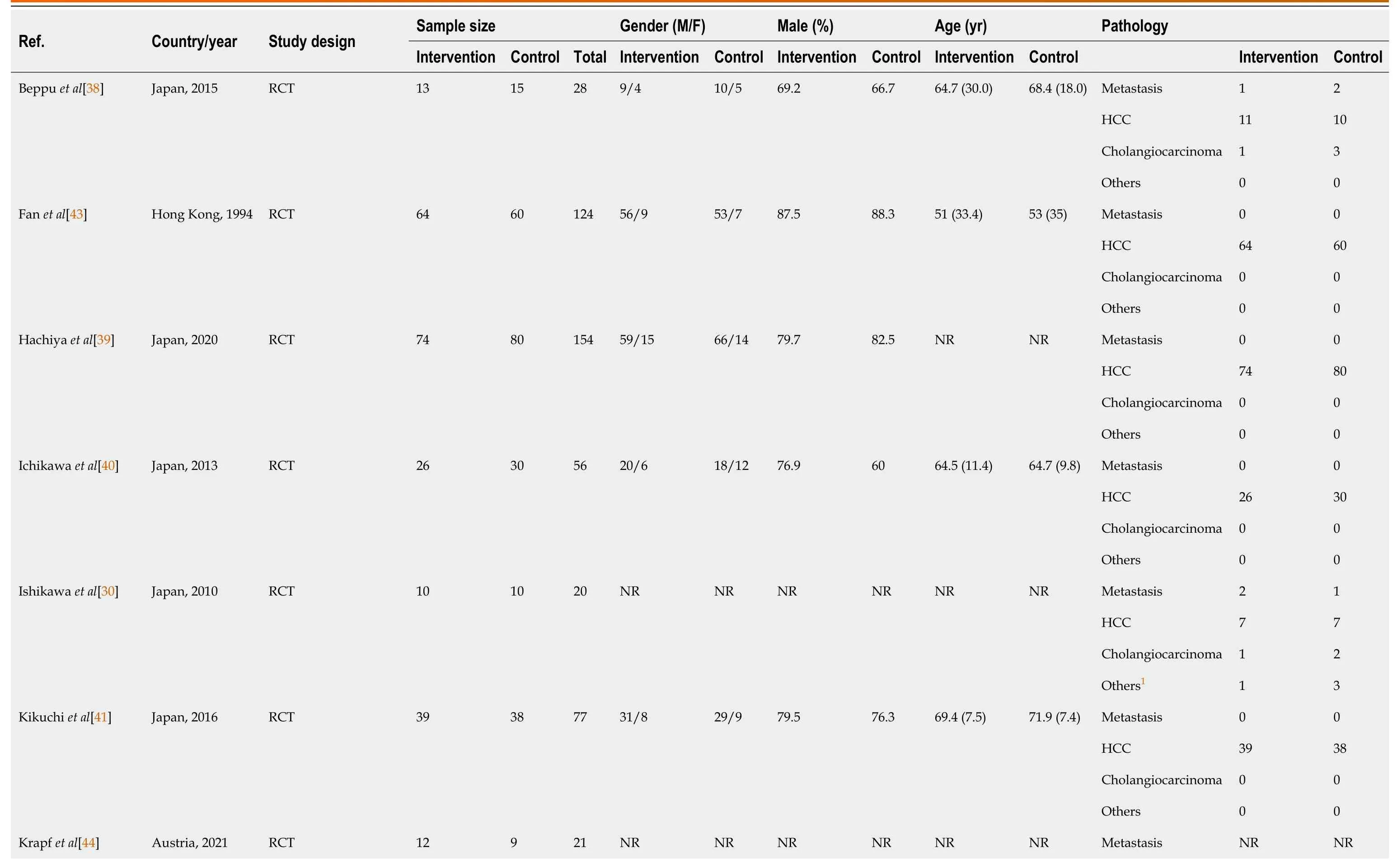

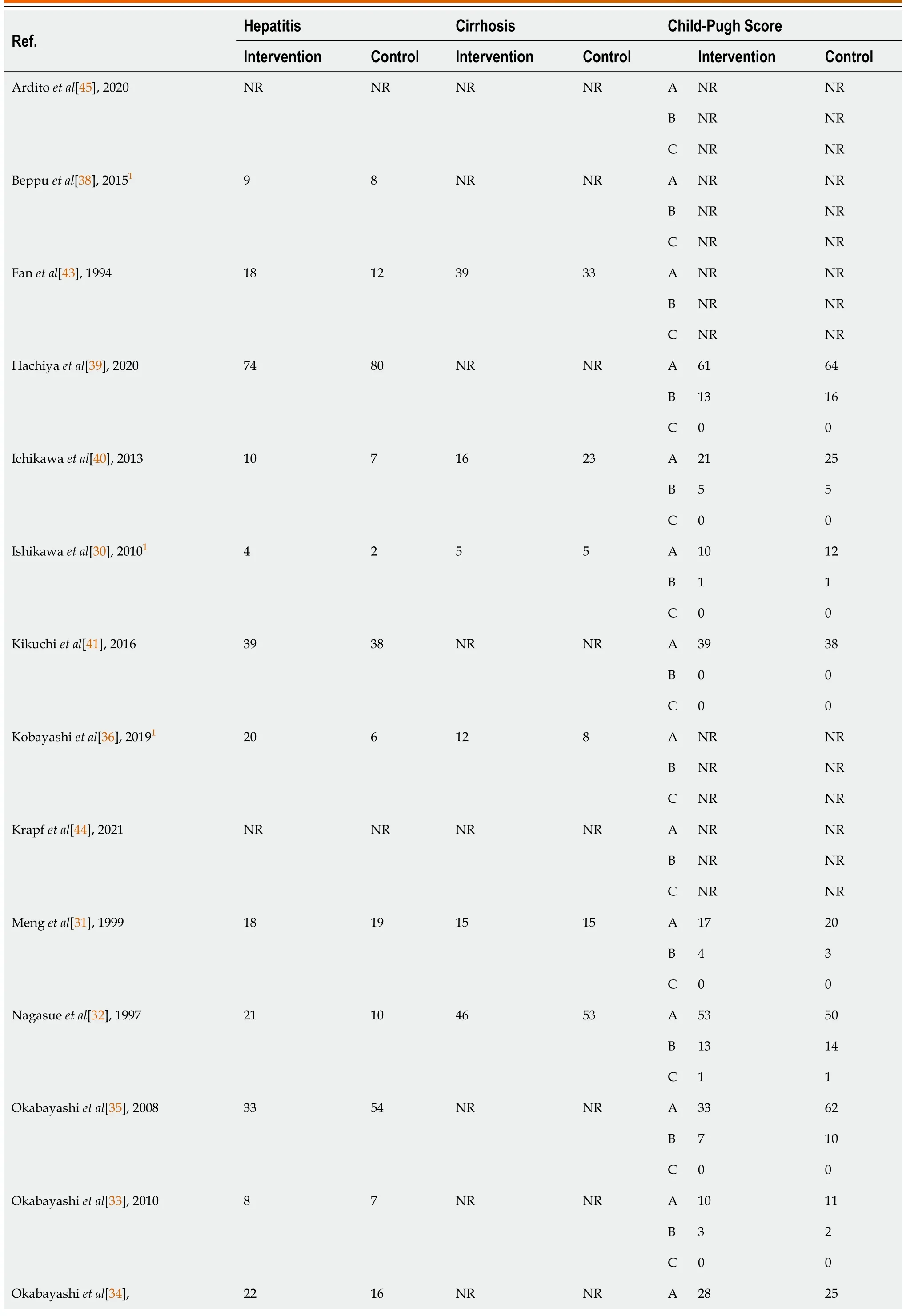

Table 2 Baseline participant information of included randomised control trials,observational studies and non-randomised trials

Data extraction

Three reviewers (Yap KY,Chi H,Ng S) independently performed the literature search and data extraction and all disagreements were resolved by mutual consensus.Data extracted include information on patient demographics (number of patients,age,sex,comorbid liver disease),cancer type and histopathology (HCC or metastatic or other cancers,tumour size and number,stage of cancer),surgical details (extent of hepatectomy,type of liver transplant) and mean duration of follow-up.

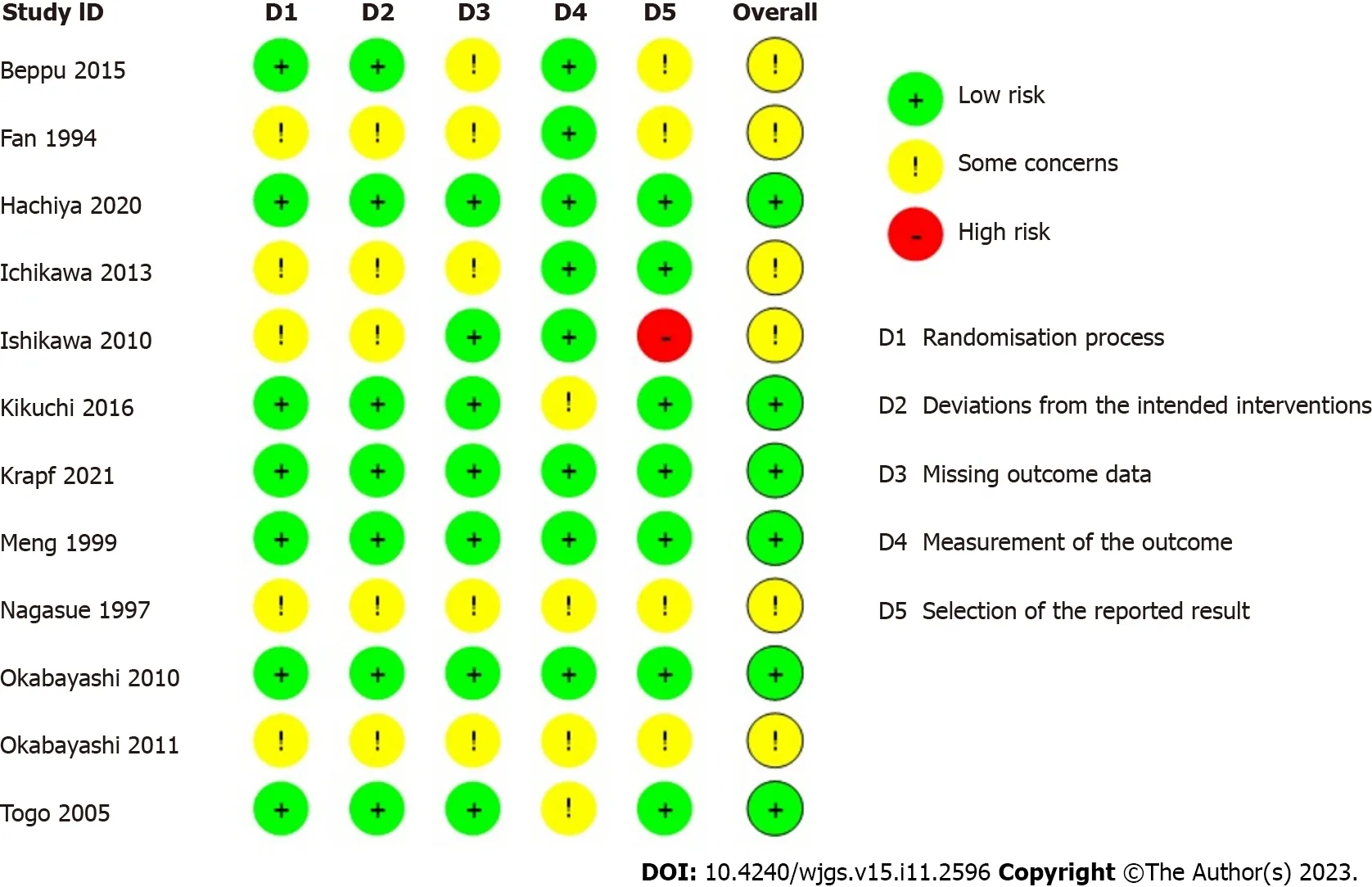

Risk of bias

Risk of bias and quality of studies were assessed.For randomised control trials (RCTs),quality control was performed by two co-authors (Yap KY and Chi H) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2[24],which assesses five domains: randomization process,deviations from intended interventions,missing outcome data,measurement of the outcome,and selection of the reported result.For observational studies,quality control was performed using the ROBINS-1 tool[25],which assesses seven domains in total: for pre-intervention (confounding and participation selection),during intervention(classification of intervention) and post-intervention (deviations from intended interventions,missing data,measurement of outcomes and selection of reported results) stages.

Outcomes of review

Primary outcomes of interest in this review were perioperative and oncological outcomes.Perioperative outcomes include postoperative morbidity,mortality,and length of stay (LOS).Oncological outcomes include recurrence and overall survival (OS).Secondary outcomes were changes in serum albumin,anthropometrics,and overall quality of life(QOL) in patients.

Postoperative infections were defined as any infectious complication arising in the postoperative period,including surgical site infections,septic complications,urinary tract infections,chest infections,liver abscesses and infected ascites.Ascites was defined as either new onset postoperative ascites or refractory ascites requiring diuretic agent for control.Allcause mortality was derived from OS in most studies,with a minimal follow-up time of 3 years (Supplementary Table 3).Recurrence was defined as reappearance of tumour with typical findings on imaging modalities.Changes in serum albumin were determined by comparing preoperative to postoperative measurements reported at 6-and 12-mo intervals.Anthropometrics reported by studies include body weight change,triceps skin-fold thickness and mid-arm circumference,but only body weight changes were included in this analysis.

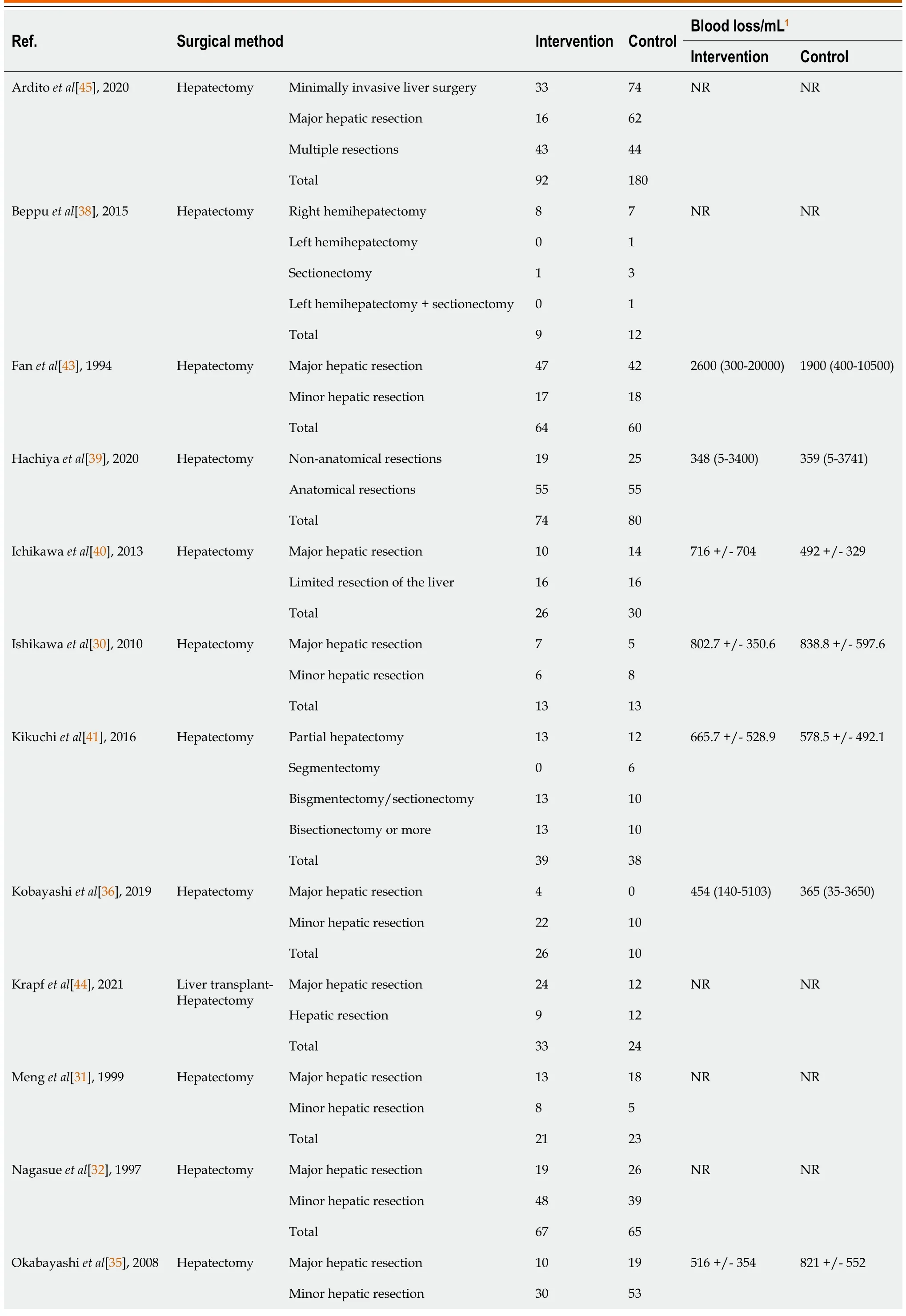

Table 3 Relevant surgical details of included studies

Statistical analysis

Review Manager version 5.4 was used to pool and analyse results with reference to approaches from the Cochrane Handbook[26].In studies without SD,P-values or confidence intervals (CI) were converted to SD.For studies without SD,P-values,and CI,we used the square-root of weighted mean variance of all other studies to estimate the SD[27].Preintervention baseline imbalances were corrected using the simple analysis of change scores method for panel data and longitudinal outcomes.In studies reporting the outcome in different scales,a simple unit conversion was performed.Inverse variance was used to derive the pooled outcomes.The random-effects model was used in accounting for betweenstudy variance.I2and τ2statistics were used to present between-study heterogeneity: Low heterogeneity (I2< 30%),moderate heterogeneity (I230%-60%),and substantial heterogeneity (I2> 60%).Two-sidedPvalue of < 0.05 was regarded as significant[26,28,29].The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Vishal G Shelat from National University of Singapore.

RESULTS

Study selection

A systematic search identified 8024 studies,of which 2949 duplicate studies were excluded.Subsequent screening of title and abstract performed independently by authors (Yap KY,Chi H,Ng S) identified 50 studies for full-text evaluation.Finally,12 prospective RCTs and 4 non-randomised studies (1 non-randomised trial and 3 observational studies) were included.A detailed PRISMA diagram is shown in Figure 1.The studies included were assessed for risk of bias,with a summary of the assessment shown in Figure 2 and Table 1 for trials and non-interventional studies,respectively.The PRISMA checklist is appended in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 1 Preferred reporting items of systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram of study selection.

Figure 2 Risk of bias assessment of included randomised control trials,using version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).

Baseline characteristics

The sixteen studies comprised a total cohort of 1389 patients.645 patients were randomized into the intervention group,consisting of various perioperative regimens of BCAA supplementation,and 744 patients into the control group.The total sample mean age is 60.5 years,intervention mean age is 62.3 years,control mean age is 58.9 years,and the total sample male is 78.7%.Table 2 summarises the baseline data of included studies.The subsequent tables outline surgical details(Table 3) and the presence and severity of comorbid liver diseases (Table 4).

Table 4 Presence and severity of liver diseases in patients of included studies

Use of BCAA supplementation

The BCAA supplementation used were mainly Aminoleban EN (Ajinomoto Pharma,Tokyo,Japan)[30-37] and Livact(Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd.,Tokyo,Japan)[37-42].The compositions of Aminoleban EN and Livact are compared in Supplementary Table 4.Three studies used generic BCAA supplements[43-45].The BCAA supplements were administered perioperatively in varying dose and duration,while patients in the control groups did not receive BCAA supplements for the same specified duration.Table 5 summarises the intervention and control protocol of all included studies.Patients were not blinded due to the lack of suitable placebos that share similar taste to the BCAA supplements.

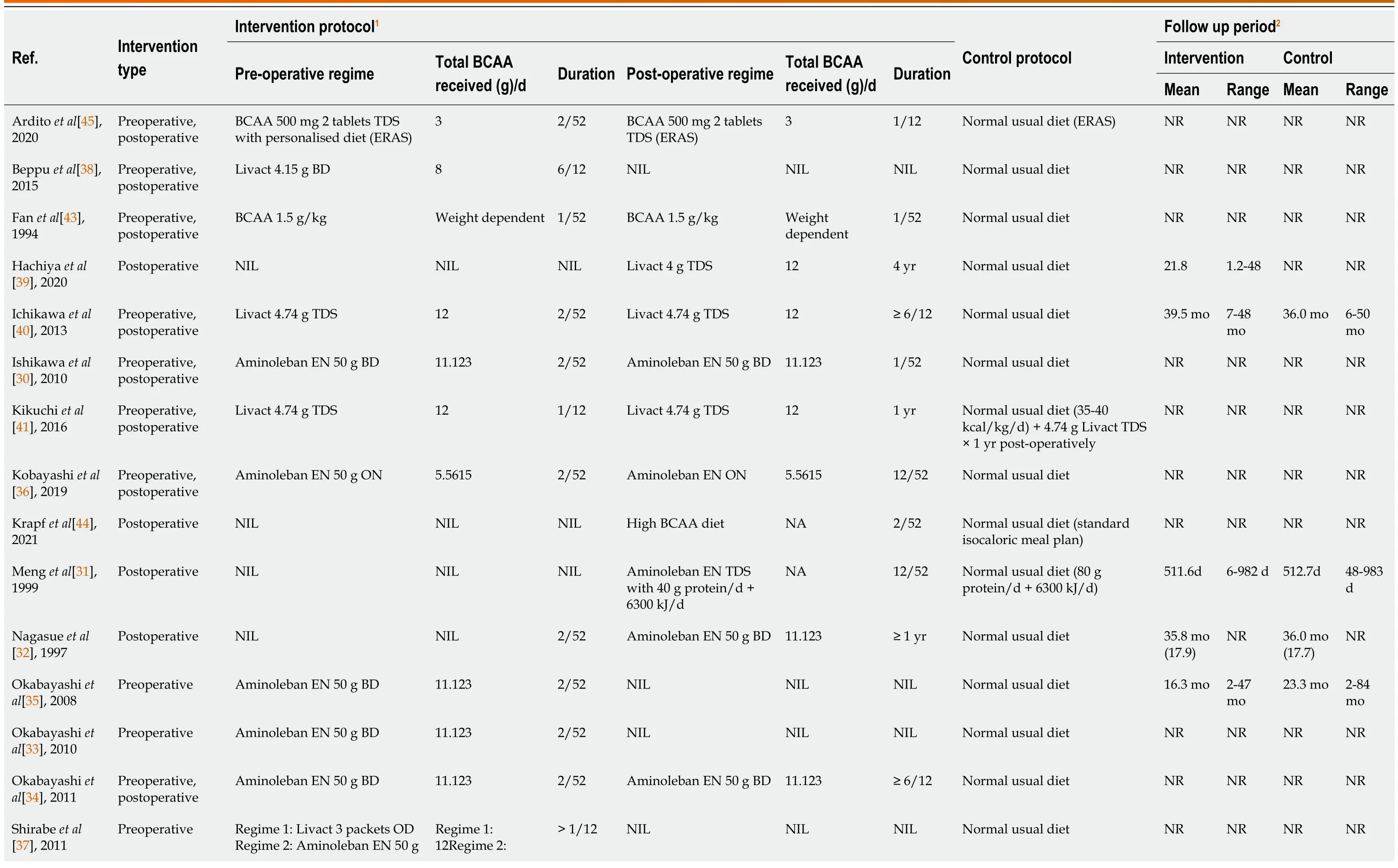

Table 5 Intervention and control protocol for all included studies

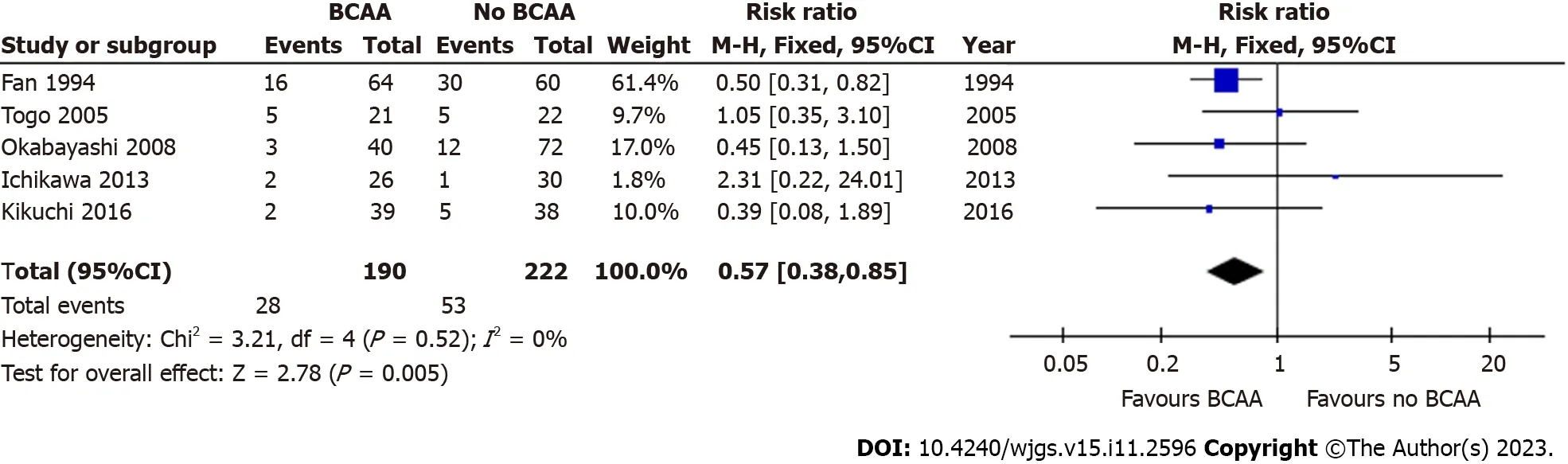

Postoperative infections

Seven out of sixteen studies[30,31,35,36,40,41,43] including 473 patients (227 in the BCAA group and 246 in the control group) reported data on postoperative infections.There was low statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2=0%).Postoperative infections were found to be significantly lower in the BCAA group [risk ratio (RR)=0.58 (95%CI: 0.39 to 0.84),P=0.005] (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Forest plot of meta-analysis on postoperative infection. BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

In a study involving BCAA supplementation in liver transplant patients,Shirabeetal[37] discovered that normal usual diet without BCAA supplementation significantly increased the risk of postoperative bacteraemia [OR=4.32 (95%CI:1.137 to 16.483),P=0.031].Although more than half of the study population had liver cancer,the study was not included in the meta-analysis as it was unclear if the effect of BCAA supplementation was generalisable to liver cancer patients.

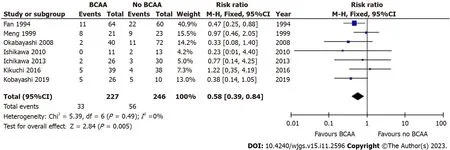

Postoperative ascites

Five out of sixteen studies[35,40-43] including 412 patients (190 in the BCAA group and 222 in the control group) reported data on postoperative ascites.There was low statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2=0%).Postoperative ascites was found to be significantly lower in the BCAA group [RR=0.57 (95%CI: 0.38 to 0.85),P=0.005] (Figure 4).Additionally,Kikuchietal[41] reported that the incidence of refractory ascites and/or pleural effusion in the BCAA group was significantly lower than in the non-BCAA group (P=0.047).

Figure 4 Forest plot of meta-analysis on all-cause postoperative ascites. BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

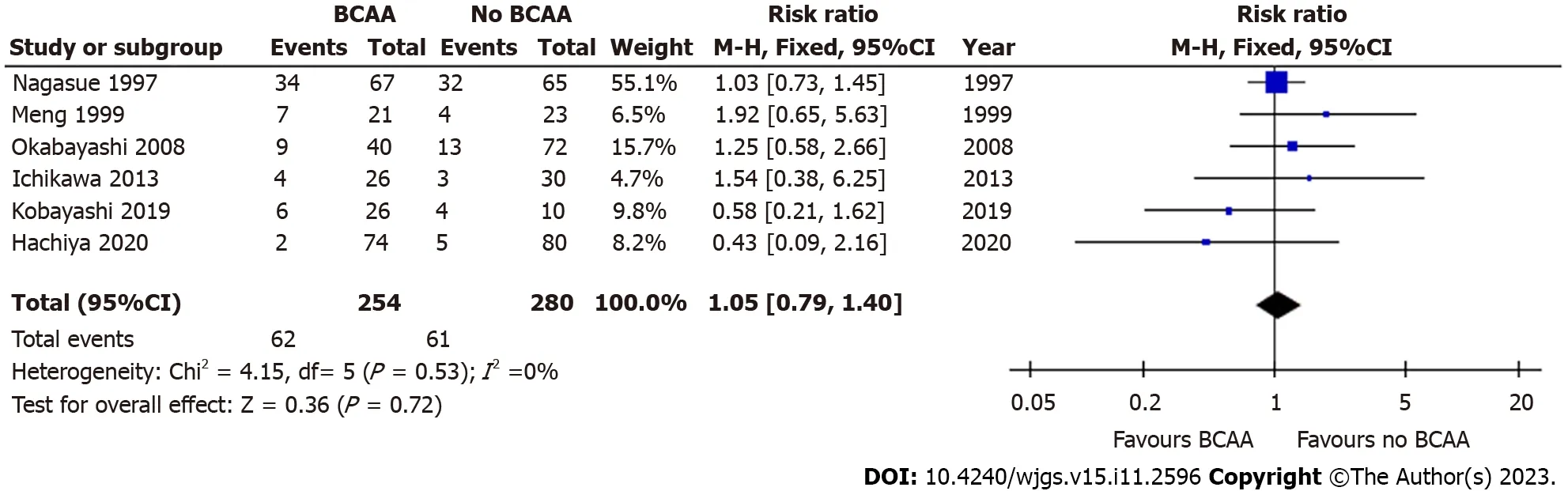

All-cause mortality (> 3 years follow-up)

Six out of sixteen studies[31,32,35,36,39,40] including 534 patients (254 in the BCAA group and 280 in the control group)reported data on mortality due to all causes (> 3 years follow-up).Follow-up periods were between 3-4 years for most included studies,and 3.5-6 years for one study.There was low statistical heterogeneity between included studies (I2=14%).There was no evidence of significant difference between the BCAA and control groups for all-cause mortality [RR=1.05 (95%CI: 0.79 to 1.40),P=0.72] (Figure 5).A separate analysis did not find any significant difference in 90-day mortality between the BCAA and control group [RR=1.69 (95%CI: 0.23 to 12.24),P=0.60] (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 5 Forest plot of meta-analysis on all-cause mortality. BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

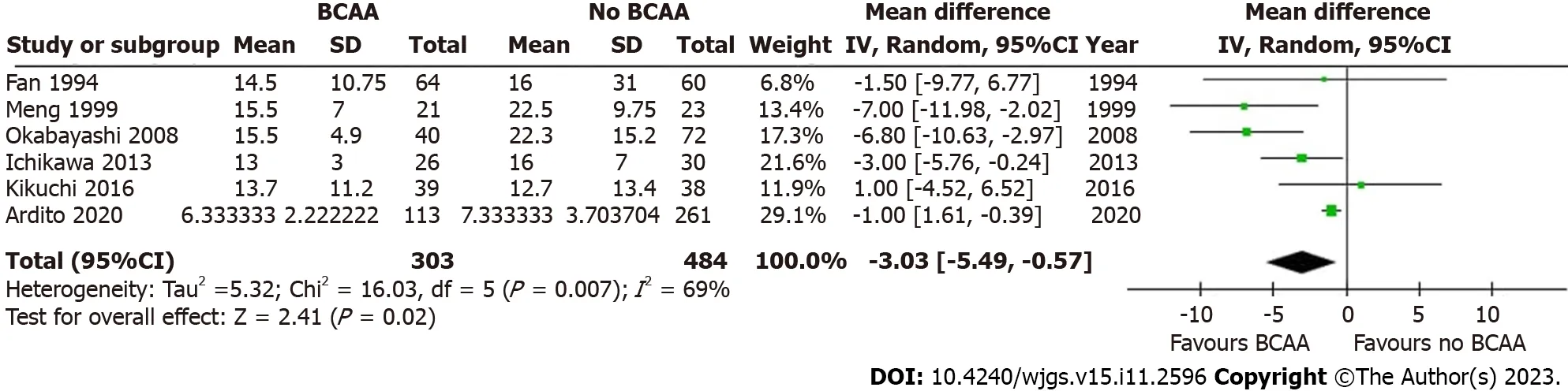

LOS

Six out of sixteen studies[31,35,40,41,43,45] including 787 patients (303 in the BCAA group and 484 in the control group)reported LOS data.There was considerable statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2=69%),and a random effects model was employed.LOS was reduced by 3.03 d in the BCAA group compared to controls [weighted mean difference(WMD)=-3.03 d (95%CI: -5.49 to -0.57),P=0.02] (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Forest plot of meta-analysis on length of hospital stay. BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

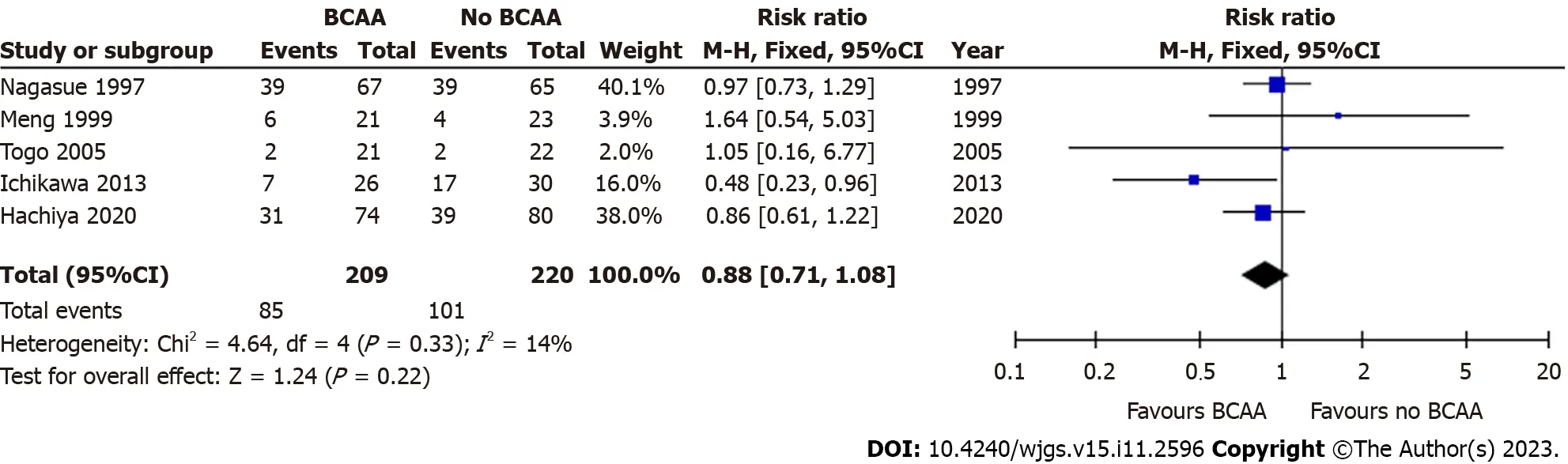

Recurrence

Five out of sixteen studies [31,32,39,40,42] including 429 patients (209 in the BCAA group and 220 in the control group)reported data on cancer recurrence.Median follow-up period varied from 12 to 30 mo.One author reported recurrence but was not included in analysis as recurrence was not an end point in the original study[34].A subgroup analysis in Hachiyaetal[39] of patients under 72 years of age with haemoglobin A1C levels below 6.4% revealed that recurrence-free survival was higher in the BCAA group compared to the control group (P=0.015).There was low statistical heterogeneity between included studies (I2=0%).There was no statistically significant difference between the BCAA and control groups for recurrence [RR=0.88 (95%CI: 0.71 to 1.08),P=0.22] (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Forest plot of meta-analysis on recurrence. BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

OS

Four out of sixteen studies[35,36,39,40] reported OS data.There was low statistical heterogeneity (I2=0%).OS did not differ significantly between the BCAA and control groups [hazard ratio=1.26 (95%CI: 0.72 to 2.21),P=0.41] (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Forest plot of meta-analysis on overall survival. BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

Figure 9 Forest plot of meta-analysis on change in serum albumin at 6 mo postoperatively. BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

Figure 10 Forest plot of meta-analysis on change in serum albumin at 12 mo postoperatively. BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

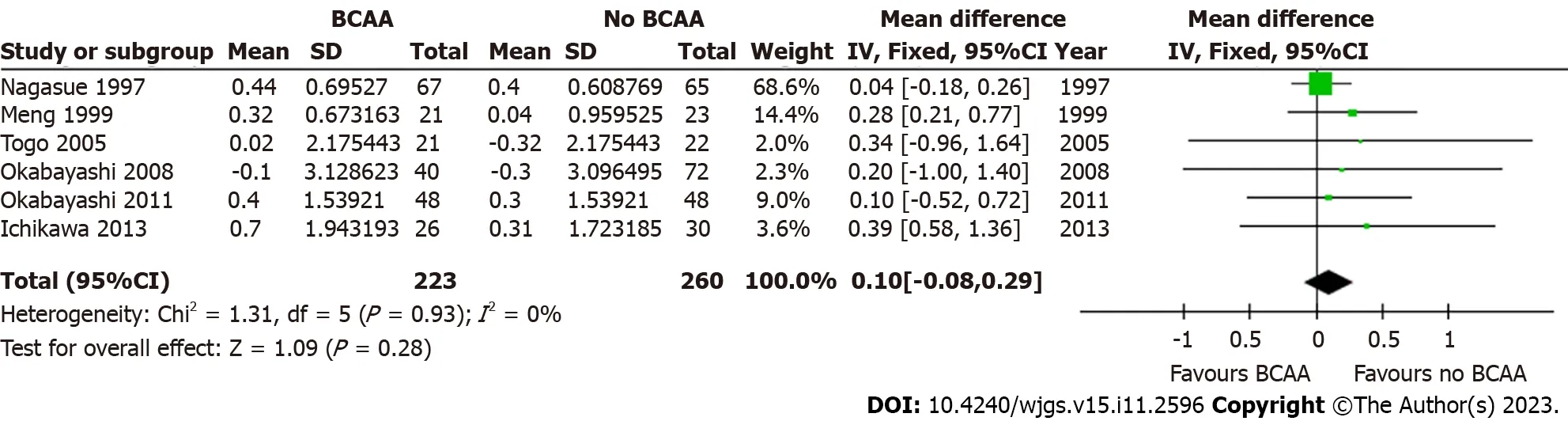

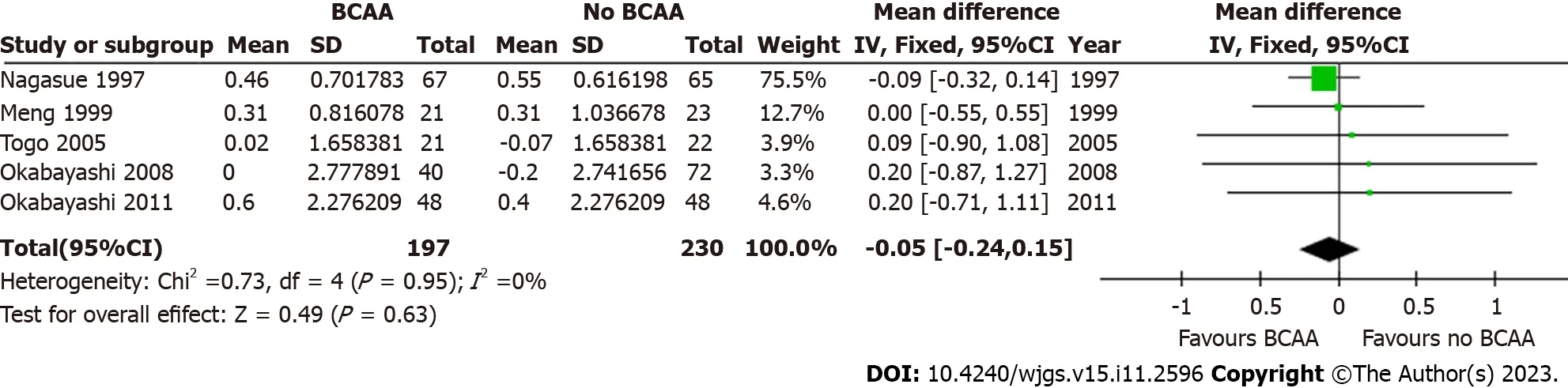

Postoperative change in serum albumin

Five out of sixteen studies[31,32,34,35,42] including 427 patients (197 in the BCAA group and 230 in the control group)reported data on change in serum albumin.There was low statistical heterogeneity (I2=0%).While individual studies reported faster albumin increase in the intervention group compared to the control group[22],change in serum albumin was not significant at 6 mo [WMD=0.10 (95%CI: -0.08 to 0.29),P=0.28] and 12 mo [WMD=-0.05 (95%CI: -0.24 to 0.15),P=0.63] (Figures 9 and 10).

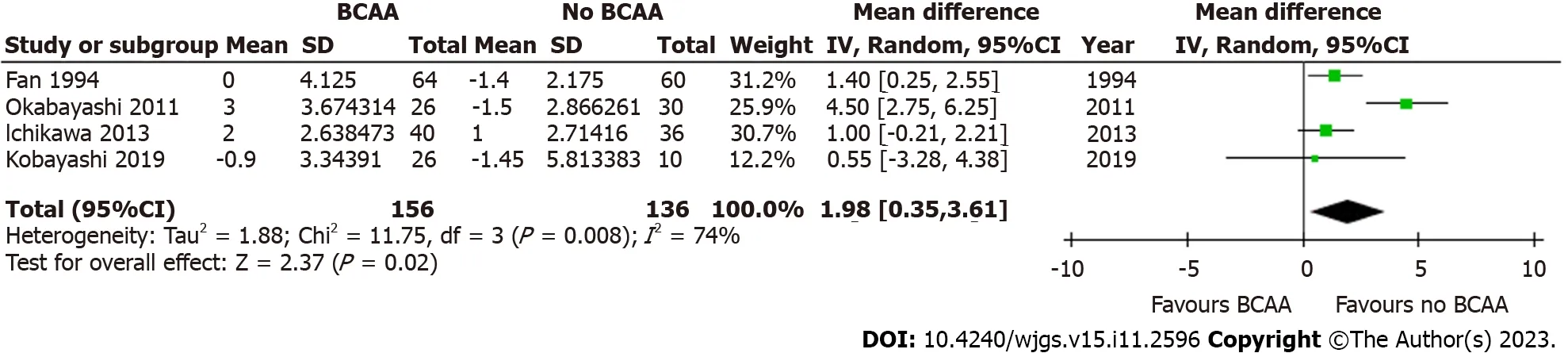

Anthropometrics

Four out of sixteen studies[34,36,40,43] including 292 patients (156 in the BCAA group and 136 in the control group)reported data on postoperative body weight change.There was considerable heterogeneity between studies (I2=74%),and a random effects model was employed.Postoperative body weight increased significantly by 1.98 kg in the BCAA group [WMD=1.98 kg (95%CI: 0.35 to 3.61),P=0.02] (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Forest plot of meta-analysis on postoperative body weight change for branched chain amino acid group relative to control.BCAA: Branched chain amino acid;CI: Confidence interval.

QOL

Three out of sixteen studies[32,34,44] reported data on QOL measures.Krapfetal[44] used the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) to look at physical,psychological,and social functions across 30 questions,and found that there was no significant difference between study groups.However,the study authors noted that patients in the BCAA group had a greater amount of food intake and significantly better subjective rating of the meals.

Okabayashietal[34] using the short-form 36 (SF-36) health sheet reported significant improvement in all 8 parameters(physical functioning,role physical,bodily pain,general health perceptions,vitality,social functioning,role emotional and mental health) in the BCAA group at the 12-month follow-up while the control group shown no significant differences in postoperative QOL.

Nagasueetal[32] used the Kanovsky scale to evaluate performance status and reported that the percentage change from baseline to the 12 mo follow-up was significantly higher in the BCAA group.

Other outcomes

It is worth nothing that two of the sixteen studies included in this review described unique outcomes of BCAA supplementation.Beppuetal[38] found that patients undergoing portal vein embolisation (PVE) and subsequent major hepatectomy had significantly greater functional liver regeneration after PVE (P=0.079) and better postoperative outcomes in the BCAA group compared to controls.A 2010 study by Okabayashietal[33] concluded that BCAA supplementation resulted in significantly reduced immediate postoperative insulin resistance (P=0.039),improved blood glucose levels and decreased need for insulin therapy in liver cancer patients.

DISCUSSION

This study shows perioperative BCAAs supplementation increases body weight,reduces infection,LOS and ascites in cancer patients undergoing liver surgery.

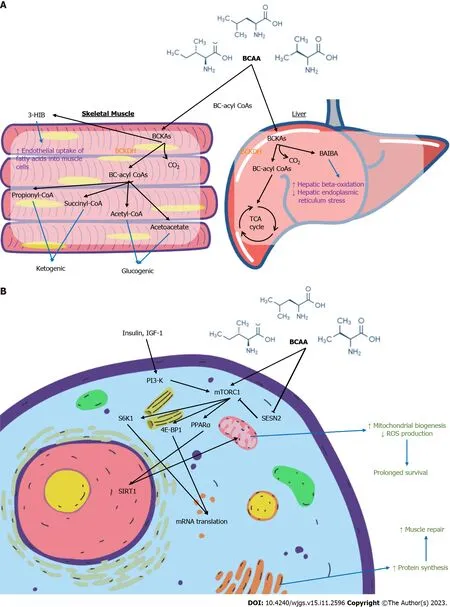

BCAAs are essential amino acids and contribute to protein synthesis,act as precursors of the tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates and are involved in key signalling pathways[46-48].Figure 12A summarises the molecular effects of BCAA on skeletal muscle and liver.Figure 12B summarises the cellular signalling pathways involving BCAA with downstream effects.Leu,the most abundant amino acid,plays a major role in protein synthesis and cellular growth.It promotes mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway activation by binding to Sestrin2,preventing the latter from inhibiting mTOR complex 1 activity[49].This contributes to downstream phosphorylation of ribosomal proteins and upregulates mRNA translation[50].Val catabolites also serve signalling functions,particularly 3-hydroxyisobutyrate (3-HIB) and betaamino-isobutyric acid (BAIBA).3-HIB promotes the endothelial uptake of fatty acids into muscle,acting as an intermediary between protein and lipid metabolism[51].BAIBA promotes hepatic beta-oxidation and reduce hepatic endoplasmic reticulum stress[52].Ile is less well-studied.Some authors have postulated its immune modulating role in inducing the expression of host defence peptides and improving innate immunity by maintaining skin mucus barrier[53,54].

Figure 12 Branched chain amino acid. A: Biochemical effect of Branched chain amino acid (BCAA) on skeletal muscles and the liver;B: Signalling pathways involving BCAA.

BCAAs in liver disease

Over 85% of liver cancer patients are cachectic[55],resulting from malignancy and protein energy malnutrition on a background of cirrhosis[56].Liver surgeries are often associated with ischemia-reperfusion periods.Poor nutritional status further exacerbates ischemic injury by accelerating glycolysis and rapidly depleting adenosine triphosphate,leading to irreversible cellular necrosis[57-59].BCAA supplementation is well-established in liver disease.The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism[60] recommend long-term oral BCAA supplements (0.25 g × kg-1× d-1) in patients with advanced cirrhosis to improve event-free survival or QOL.The American Association for the Study of Liver[61] recommend BCAA administration as an alternative or additional agent to treat hepatic encephalopathy in patients who are unresponsive to conventional therapy.However,the evidence of benefit for BCAAs in liver cancer patients managed by surgical approaches is less clear.

Importance of optimising nutrition in perioperative patients

Despite many studies reporting a strong association between malnutrition and poor surgical outcomes,oncological patients often lack opportune time to delay treatment for nutritional optimisation.In a study of nutrition and HCC,Huangetal[62] noted that patients assessed by dietitians to be malnourished had a significantly higher rate of major complications[63].With an increasing focus on optimisation of postoperative surgical recovery,enhanced recovery after surgery protocols and prehabilitation initiatives have also emphasised the importance of perioperative nutrition[64].

Relevance of BCAAs to outcomes

This review investigated perioperative and oncological outcomes of BCAA supplementation in patients undergoing surgery for liver cancers unlike the previous review that included diverse oncological diagnoses[22].We demonstrated that BCAA supplementation significantly reduced postoperative complications,with over 40% relative risk reduction of postoperative infection and ascites.The BCAA group also had slightly higher body weight and performed better on both perceived and actual QOL metrics,suggesting that BCAA intake can optimise recovery and function after surgery.

Effect of BCAA on oncological outcomes

BCAA supplementation had no impact on cancer recurrence and OS.This is consistent with the conclusions of recent meta-analyses[22,65].The relationship between BCAA and liver cancer at the molecular level has been explored[66-68].BCAAs suppress the development of liver cancers in rodent models[69,70],presumably improving insulin resistance in obesity or diabetes mellitus.Insulin resistance is involved in the pathogenesis of HCC,as insulin has oncogenic properties on HCC cells,stimulating cell growth and inducing anti-apoptotic activity[71,72].Another study postulated suppression of VEGF expression in tumour cells as an alternative mechanism[73].The catabolism of BCAAs has also been extensively implicated in carcinogenesis[67] through various molecular pathways,including accumulation of branched-chain αketoacids and activation of the mTORC1 pathway[74,75].Ericksenetal[76] validated oncogenic pathways and linked high dietary BCAA intake to tumour burden and mortality specifically in HCC patients.

Given the apparent contradictory effects of BCAA on liver cancer development and prognosis,it may be challenging to interpret our findings.BCAAs may potentially improve liver function and body weight postoperatively but also contribute to tumour recurrenceviathe above-mentioned pathways.The beneficial oncological effects of BCAA supplementation remain inconclusive.

Effect of BCAA on postoperative complications

While oncological outcomes do not support routine use of BCAA supplementation in the perioperative period,our review found that the risk of postoperative infection and ascites were significantly lowered in BCAA groups.

Postoperative infection is a frequent complication of hepatic resection,with reported rates of up to 25%[77,78].It can be associated with significant morbidity in the absence of early recognition and treatment[79].After major liver surgery,impairment of innate immune function increases host susceptibility to infection[80].Furthermore,surgery in HCC patients results in higher risk of infectious sequelae,presumably due to underlying cirrhosis and chronic liver dysfunction,bile leak with risk of abdominal sepsis,and postoperative pneumonia due to upper abdominal incision[81].Another major risk factor for infection is malnutrition[82-85].BCAA supplementation directly improves patients’preoperative nutritional status[86].BCAAs also play an essential role in immune cell function relating to protein synthesis[87],and in immune regulation in patients with advanced cirrhosis[88-90].

Postoperative ascites is reported in 5% to 56% patients undergoing hepatectomy[91],and is associated with liver failure[92,93].Chanetal[94] described higher 1-year mortality and lower recurrence-free survival rates attributed to postoperative ascites.

BCAAs increase the synthesis and secretion of albumin by hepatocytes[95],and improve impaired metabolic turnover of albumin in cirrhotic patients[96].Fukushimaetal[97] reported that BCAAs effectively improved the oxidisation/reduction imbalance of albumin in cirrhosis.In our study,BCAA supplementation did not significantly increase postoperative serum albumin levels.The underlying mechanisms behind the demonstrated efficacy of BCAA supplementation in reducing postoperative ascites remain uncertain.

Effect of BCAA on QOL

2 out of 3 included studies[34,44] demonstrated significant improvement in QOL with BCAAs,but differing methodologies and domains for assessment were employed.Krapfetal[44] noted a significantly higher subjective rating of high BCAA content diet compared to normal usual diet,despite similar preparation methods and staff.If such an outcome is indeed replicated in future QOL studies,it may represent a potential benefit of BCAA supplementation in improving oral intake and avoiding malnutrition in post-surgical patients.These results are consistent with QOL improvements seen in RCTs on BCAA supplementation in cirrhosis[98,99].

Overall,more robust,large-scale clinical studies of surgical patients with liver cancer would need to be conducted with standardisation of total calorie and protein intake in intervention and control groups to conclude on the risk-benefit calculation of BCAA supplementation.Future studies should report BCAA to total protein intake ratio,protein to calorie ratio and type of BCAA to understand cause effect relation on perioperative outcomes of BCAA supplementation.

Side effects of BCAA

We reviewed side effects reported from routine BCAA ingestion in the included studies.Most studies did not report side effects with the exception that one RCT[43] reported 2 events (3%) relating to intravenous administration,while another[32] reported that 3 patients were unable to continue with BCAA administration due to adverse reactions.Overall,BCAAs have an extremely low incidence of side effects in the included studies.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include data pooling from newer RCTs and multiple real-world observational studies.While RCTs are considered the gold standard for ascertaining the efficacy and safety of a treatment,their methodologies may limit generalizability.The inclusion of observational studies provides more generalizable results applicable in the realworld situation.Since both types of study design have their strengths and limitations,they provide insight into the efficacy of BCAA supplementation.

Though many Japanese studies were included,exclusion of non-English articles may have led to language biases as a potential confounding factor in our conclusions.The included studies had varying doses of BCAA supplementation and a lack of data on composition of normal usual diet in the participating institutions.Most of the patients in this review had Child-Pugh score A cirrhosis and thus might not be malnourished.Further,there is no population data to suggest that HCC patients have deficiency of BCAA.A lack of long-term follow-up data in the included studies makes it difficult to study the impact of BCAA supplementation on oncological outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Perioperative BCAA administration increases body weight and reduces postoperative infection,ascites,and LOS in liver cancer patients undergoing surgery.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Branched chain amino acids (BCAA) show promising results in improving surgical outcomes in liver cancer patients and potential for routine use.

Research motivation

Current studies on BCAA supplementation show varying results but with no clear conclusion and no updated reviews on the matter.

Research objectives

To provide the most updated review on whether BCAA supplementation provides measurable benefits in liver cancer patients for surgical intervention.

Research methods

Current trials and studies on BCAA supplementation in liver cancer patients undergoing surgery were appraised by three independent authors.Studies were identified and data extracted for meta-analysis of the relevant outcomes.

Research results

Perioperative BCAA supplementation reduced postoperative infections,length of stay and increased body weight in the studied patient groups but did not improve mortality,oncological recurrence,and long-term survival.

Research conclusions

This review has shown that BCAA supplementation improves postoperative outcomes with no significant side effects.However,benefits on oncological outcomes remain inconclusive.

Research perspectives

This review highlights the possible routine use of BCAA for liver cancer patients for surgical intervention.Further clinical research can be directed at assessing optimal BCAA supplementation regime for such patients.

FOOTNOTES

Co-first authors:Kwan Yi Yap and HongHui Chi.

Author contributions:Yap KY acquisition of data,analysis and interpretation of data,drafting the article,revising the article,final approval;Chi H acquisition of data,analysis and interpretation of data,drafting the article,revising the article,final approval;Ng S acquisition of data,interpretation of data,final approval;Ng DH revising the article;Shelat VG supervision,critical revision,final approval.Yap KY and Chi H contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.This research is the product of the collaborative effort of the team,and the designation of co-first authors authorship is reflective of the time and effort invested by the co-first authors into the completion of the research.Furthermore,the decision of co-first authors authorship acknowledges and respects the equal contribution made by both co-first authors throughout the process of writing the paper.As a whole,the team believes that designating Yap KY and Chi H as co-first authors is appropriate and reflective of the team’s collective spirit and wishes.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors deny any conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement:The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist,and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license,which permits others to distribute,remix,adapt,build upon this work non-commercially,and license their derivative works on different terms,provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial.See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Singapore

ORCID number:Kwan Yi Yap 0000-0002-6766-9222;HongHui Chi 0009-0003-8888-0590;Sherryl Ng 0009-0003-1321-2408;Doris HL Ng 0009-0005-3360-6986;Vishal G Shelat 0000-0003-3988-8142.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies:Singapore Medical Association,12617I.

S-Editor:Qu XL

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Wu RR

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023年11期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2023年11期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery的其它文章

- Systematic sequential therapy for ex vivo liver resection and autotransplantation: A case report and review of literature

- Gastric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor,a rare mesenchymal neoplasm: A case report

- Comprehensive treatment and a rare presentation of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: Two case reports and review of literature

- Isolated traumatic gallbladder injury: A case report

- Metachronous primary esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and duodenal adenocarcinoma: A case report and review of literature

- Organ sparing to cure stage IV rectal cancer: A case report and review of literature