Liver transplant in primary sclerosing cholangitis: Current trends and future directions

Yash R Shah,Natalia Nombera-Aznaran,David Guevara-Lazo,Ernesto Calderon-Martinez,Angad Tiwari,SriL akshmiDevi Kanumilli, Purva Shah, Bhanu Siva Mohan Pinnam, Hassam Ali, Dushyant Singh Dahiya

Abstract

Key Words: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; Liver transplantation; Management; Psychosocial outcomes; Pathogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic immune-mediated cholangiopathy characterized by inflammation and scarring of the biliary tree, affecting both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts.Its etiology remains idiopathic and it presents a wide spectrum of symptoms and complications.PSC is a rare condition with a global incidence rate ranging from 0 to 1.58 cases per 100000 per year, and a prevalence bracket of 0 to 31.7 cases per 100000 persons[1].Recent research northern Europe has shown an increasing frequency of both new cases and overall instances of PSC[1].As compared to the adult population, the incidence and prevalence of PSC is lower in the pediatric population at 0.2 and 1.5 per 100000 children[2].

Currently, there is no proven no medical therapy to treat effectively or alter the natural history of PSC[3].As a result, the prognosis of this condition is poor, and it is strongly associated with an elevated risk of developing liver cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease, often necessitating liver transplantation (LT)[4].The development and progression of PSC involve a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors, although the contribution of genetic factors remains limited[5].On the other hand, environmental factors, particularly the gut microbiota, have gained increasing attention in PSC development[6].Additionally, approximately 70% of PSC patients have concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which serves as a strong risk factor for colon, bile duct, and gallbladder cancers[7].The co-occurrence of IBD and PSC is evident, with 2%-7.5% of IBD patients developing PSC[4].

Advancements in noninvasive imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), have improved the understanding and diagnosis of PSC, including its relationship to LT.PSC accounts for approximately 10% of all liver transplants performed annually[4-8].However, post-transplant recurrence of PSC has been reported, highlighting the need for a better understanding of its underlying pathogenesis and the development of more comprehensive therapeutic strategies[9].Despite these challenges, long-term outcomes following transplantation are encouraging, with a 5-year survival rate of 89% and favorable graft survival rates[10].

PSC is a poorly understood domain and has been presented with a huge void in terms of concrete solutions that are yet to be fulfilled.In this review, we discuss the current understanding of PSC’s pathogenesis, clinical presentation, management options, the scope of LT, and associated challenges.

DISCUSSION

Pathogenesis of PSC

Inflammation and fibrosis of the bile ducts are two primary processes in the pathogenesis of PSC.However, the mechanism of inflammation and fibrosis in PSC are not fully understood.It is believed that various factors such as Ischemic, traumatic, infectious, autoimmune, or toxic injuries cause damage to cells, leading to the release of “dangerassociated molecular patterns (DAMPs)”.These DAMPs activate the innate immune system through “pattern recognition receptors”[11].Chronic inflammatory response mediated by DAMPs and the recruitment and activation of innate or adaptive immune cells play a critical role in initiating and perpetuating the activation of profibrogenic cells into myofibroblasts through the release of cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS).ROS and oxidative stress can induce hepatocyte injury, cell death, and parenchymal cell proliferation, along with altered remodeling and increased expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases[12].Additionally, certain cytokines produced by damaged cells, such as interleukin (IL)-1a, IL-33, and others, directly or indirectly promote the development of a Th2 immune response, which is believed to promote fibrosis.Th2 immune response is recognized to have profibrotic properties through the release of IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13[11,13].However, the exact mechanisms and interactions between these processes are still being investigated in the context of PSC pathogenesis.

Role of Bile Ducts in PSC

Cholangiocytes can be activated by various insults such as infections, cholestasis,etc., leading to increased proliferation along with pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory secretions through pleiotropic autocrine and paracrine mechanisms[14].Persistent biliary cell damage causes an inflammatory reaction that leads to a pathological reparative reaction with excessive deposition of scar tissue around the injured ducts.The biliary epithelium is exposed to cytokines and chemokines secreted by innate and adaptive immune cells in response to DAMPs.If biliary homeostasis is not restored, there will be a maladaptive chronic inflammatory response stimulating the deposition of connective tissue (Figure 1)[14].

Genetic and Environmental factors in pathogenesis of PSC

Genetic factors play a significant role in PSC pathogenesis.Studies have demonstrated an increased risk of PSC among first-degree relatives of patients with the disease[15].Genome-wide association studies have identified over 20 susceptibility genes for PSC, with the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex on chromosome six showing the strongest association[16-20].Patients with PSC exhibit chromosomal instability and immunosenescence, as evidenced by higher rates of short telomere length and telomere aggregates compared to patients with IBD[21,22].It is important to note that genetic findings explain less than 10% of the disease liability, while environmental factors account for over 50% of it[22].

The microbiome has also been implicated in PSC pathogenesis, with bacteria potentially triggering an aberrant immune response and perpetuating inflammation[23].Studies have shown an enrichment ofBarnesiallaceaeandBlautiafamilies andBarnesiellacaeaegenus in PSC patients.Microbiome shifts associated with PSC are observed inClostridialesandBacteroidalesorders, with more than 80% of shifts occurring within the former order.However, the causal relationship between these shifts remain unclear due to limited sample size[24].Some environmental triggers have been investigated, indicating a higher prevalence of PSC in rural areas and a possible connection to agricultural activities, pesticides, or fertilizers[25].Close contact with dogs or cats has also been identified as a potential trigger, suggesting the pathogenic role of an unidentified agent such as a toxin or microbiome[26].Additionally, coffee consumption and smoking have been suggested as protective factors against PSC[27].

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of PSC

PSC is characterized by bile duct injury and fibrosis, leading to a variety of symptoms and signs.It is commonly associated with IBD[12].It typically affects individuals between the ages of 30 and 40, with a higher prevalence in men[28].PSC patients are identified during general health examinations or the investigation for another disease, and about 50% patients are asymptomatic[29].When symptoms occur, the most common are pruritus, fatigue, and right upper quadrant pain; less frequent symptoms are weight loss and fever[29,30].Physical exam often reveals jaundice, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and excoriation marks[29,31].PSC is a progressive cholestatic liver disease associated with complications such as bacterial cholangitis, dominant strictures, gallbladder polyps, adenocarcinoma, and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA)[29,30,32].Disease progression may differ in children due to absence of other risk factors like alcohol abuse or polypharmacy that can lead to faster progression of the liver disease[33].

Diagnosis of PSC relies on the presence of cholestasis markers [alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl (GGT) transferase], characteristic bile duct changes on imaging and the exclusion of secondary causes[29,20].The elevation of serum ALP is the commonest marker[29,32].ALP is not reliable in children as it can be elevated due to high bone turnover.So, GGT transferase is more commonly used as a diagnostic marker in the pediatric population[34].However, the transient blockage of the strictured bile ducts can create fluctuations in ALP and bilirubin levels.The total serum bilirubin level is usually normal, but an increase or fluctuations in bilirubin levels indicate the presence of dominant strictures or advanced liver disease[32,35].The dominant strictures are present in around 45% of adult patients at the diagnosis of PSC as compared to < 5% in the pediatric population[34].Additionally, serum aminotransferases are elevated 2-3 times the upper limit of normal[29].In cases of a high level of serum aminotransferases, autoimmune hepatitis should be ruled out[36].

PSC is commonly associated with an underlying IBD, with ulcerative colitis (UC) being the most prevalent.Both PSC and UC have an autoimmune component, which is reflected in the presence of autoantibodies.The most frequently reported autoantibodies in PSC and UC are perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, found in 26%-94% of PSC cases and 50%-70% of UC cases[37,38].Additional autoantibodies reported in PSC include antinuclear antibodies (present in 8%-77% of patients) and smooth muscle antibodies (present in 0%-83% of patients)[32,38].However, it's important to highlight that these autoantibodies lack specificity and are not necessary for a diagnosis of PSC.

Figure 1 Pathogenesis of disease progression in primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Imaging techniques such as abdominal X-ray and ultrasound can reveal abnormal bile ducts and exclude gallstones.However, these techniques are unable to provide a clear view of intrahepatic biliary ducts.Additionally, sclerosis does not dilate the ducts enough to be seen on imaging, resulting in suboptimal assessment in suspected cases of PSC[39].For this reason, cholangiography assessment is essential for the diagnosis of PSC, as the morphological features of PSC mainly involve biliary ductal changes, while liver parenchymal changes develop later[39].The common imaging findings in PSC seen on MRCP or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) include intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct strictures, which alternate with normal or dilated bile ducts showing a beading appearance (Figure 2)[39-41].MRCP is preferred as an initial non-invasive imaging method, while ERCP is reserved for therapeutic interventions[30,32,42,43].The sensitivity and specificity for ERCP in the diagnosis of PSC are 89% and 80% respectively[44].MRCP has shown a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 94% for diagnosis of PSC, with superior cost-effectiveness compared to ERCP[45,46].

Staging, Prognosis, and Management of PSC

PSC is staged using a four-stage system first developed by Ludwiget al[47] in 1978, which is shown in Table 1.Several good prognostic factors have been identified, including young age, female sex, small duct phenotype, and the presence of Crohn’s disease[48].In early disease, the Mayo PSC risk score can be useful in predicting short-term survival, but it cannot predict the need for LT[49,50].However, a meta-analysis has shown that the United Kingdom-PSC score and the PSC risk estimate tool are better at predicting long-term risk[51-53].The components of each prognostic score are listed in Table 2[49,52-57].

The management of PSC focuses on slowing the disease progression and managing its complications.However, there is no definitive treatment to halt the disease process.LT is a viable option for advanced cases and has shown favorable outcomes.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a hydrophilic bile acid, is commonly used in the treatment of cholestatic liver diseases and is extensively studied in PSC[58].Its mechanisms of action include protecting cholangiocytes against cytotoxic hydrophobic bile acids in early stages, stimulating hepatobiliary secretion in more advanced stages, and protection of hepatocytes against bile acid-induced apoptosis in all stages[59,60].UDCA has been shown to improve liver function tests, its impact on survival rates, prevention of CCA, or clinical symptoms is inconclusive[61-63].However, other data has shown that meaningful reductions in ALP levels have been associated with better outcomes in PSC[64-66].In addition, withdrawing UDCA may be associated with increase in fatigue, pruritus, liver biochemistries, and Mayo PSC risk score[58,67].American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) updated their guidelines on PSC management in 2022, to suggest a dose of 13-23 mg/kg/d of UDCA, with continued use if there is a reduction or normalization of ALP levels and/or improvement of symptoms after 12 mo of treatment[68].

Immunosuppressive therapies, including glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil, have been explored for PSC treatment.However, a systematic review concluded that these agents, either as monotherapy or in combination do not reduce the risk of mortality or LT, and monotherapy may increase adverse effects[69].Recent findings from a meta-analysis suggest that immune-modulating therapy may benefit patients with high baseline levels of ALP (> 420 U/L) and aspartate transaminase (> 80 U/L)[70].Nevertheless, immunosuppressive agents should be reserved for patients with overlap syndromes such as autoimmune hepatitis-PSC or IgG4-associated cholangitis[68].Ongoing clinical trials are investigating potential treatments options, such as cilofexor (a nonsteroidal farnesoid X receptor agonist), and 24-nor UDCA (a derivative of UDCA), which show promising results[71,72].

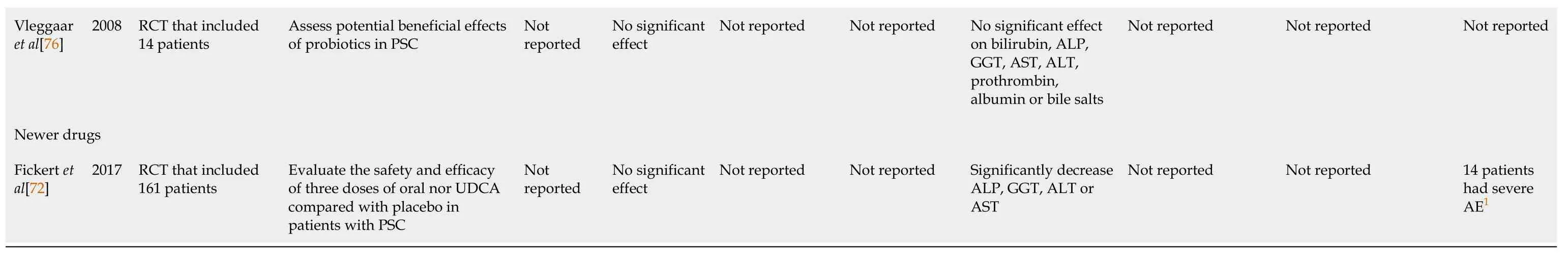

Medical management of PSC has several limitations, despite various drugs being investigated, a recent meta-analysis concluded that there is currently insufficient evidence to show differences in effectiveness measures, such as mortality,health-related quality of life, cirrhosis, or LT between any active pharmacological intervention and no intervention[73].The high risk of bias in most assessed trials further underscores the need for well-designed randomized controlled trials with adequate follow-up in order to improve pharmacological management of patients with PSC.An overview of various clinical trials and meta-analysis assessing the efficacy and adverse effects of medications used in management of PSC is described in Table 3[61-63,69,70,72,74-76].

Table 2 Overview of the clinical scores for predicting prognosis in primary sclerosing cholangitis and its components that include serum-based biomarkers and clinical features

While most cases of PSC are characterized by multifocal bile duct strictures, a few have a localized high-grade stricture (dominant stricture) superimposed on diffuse disease that can cause jaundice or cholangitis[77].Furthermore, CCA may appear as a dominant stricture[78,79].Hence, brush cytology of the biliary tree, endobiliary biopsy, and fluorescence in situ hybridization should be performed to assess it[68].AASLD recommends ERCP for the evaluation of relevant strictures as well as new-onset or worsening pruritus, unexplained weight loss, worsening serum liver test abnormalities, rising serum cancer antigen 19-9, recurrent bacterial cholangitis, or progressive bile duct dilation[68].However, it is important to consider that PSC patients undergoing ERCP have an increased risk of bacterial cholangitis and pancreatitis, so antimicrobial prophylaxis should be administered before the procedure[80-84].

Liver Transplant in PSC

Indications for liver transplant in PSC: LT is performed in patients with PSC when medical therapy has reached its limits[85].PSC is a hepatic condition with a variable clinical course.LT becomes necessary when the patient develops end-stage liver disease and complications related to portal hypertension, such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal hemorrhage, or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis[51,85].In 2006, United Network Of Organ Sharing reported that 6650 patients received liver transplants, while 17221 were on the waiting list[86].To address the insufficient number of deceased donors and long wait times, living donor liver transplant (LDLT) emerged as an alternative with favorable outcomes for acute and chronic liver diseases, provided appropriate selection criteria[87,88].

In the United States, Model For End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score is used by Organ Procurement and Transportation in Network (OPTN) to prioritize liver transplant recipients.LT is considered when MELD score is ≥ 15, indicating hepatocellular dysfunction[85].The MELD score incorporates the patient’s serum bilirubin level, international normalized ratio, and serum creatinine level[89].MELD exceptions for LT are granted to patients with at least two admissions within a 1-year period for acute cholangitis with a documented bloodstream in infection or with evidence of sepsis requiring vasopressors for hemodynamic instability, as well as those with a diagnosis of CCA[90].The inclusion and exclusion criteria for LT in patients with CCA are detailed in Table 4[68,91].The LT process involves a multidisciplinary team with different roles, as outlined in Table 5[92].

Table 3 Overview of important clinical trials and meta-analysis assessing medications used in management of primary sclerosing cholangitis

1Results of this outcome were not included in the meta-analysis.It was derived from the assessment of individual studies.GGT: Gamma-glutamyl; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; AE: Adverse effects; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine transaminase; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; UDCA: Ursodeoxycholic acid; BA: Bile acids.

Psychosocial evaluation in liver transplant candidates: Patients with PSC may experience anxiety, depression, substance use disorder, or other psychological symptoms due to the chronic and potentially progressive nature of the disease[93].35%-65% of transplant candidates meet criteria for an internalizing disorder as a result of waiting and anticipating surgery[94].Chronic illness can impact the quality of life, especially in case of conditions like PSC where patients may have unpredictable flares of symptoms.The psychological evaluation can also help in identifying coping strategies that patients can use to manage their symptoms and improve their overall well-being[93].Various psychological instruments used for psychosocial evaluation in transplant candidates are listed in Table 6[93].

Overall, the medical and psychological evaluation in PSC plays a crucial role in assessing the severity of the disease and identifying any associated conditions, as well as addressing psychological factors that may affect the patient's quality of life[93].

Ethical considerations in liver transplant candidates: Organ transplantation raises significant ethical considerations, making it one of the most controversial disciplines in medicine[95].Key ethical concerns related to organ retrieval include accurately diagnosing brain death, respecting the patient's known wishes regarding organ donation, and upholding the principle of altruism in living organ donation[96].When it comes to living organ donors, ensuring their understanding of the surgery’s risks, benefits and potential complications is crucial, especially during the informed consent process.Comprehensive discussions on short-term and long-term outcomes should take place at this stage[97].There is notable regional variability in the application and acceptance of MELD exceptions for LT.A study revealed that, despite OPTN’s clinical criteria, nearly 80% of exception applications for PSC and cholangitis were approved by regional review boards regardless of the indication[98].This highlights the need for a standardized national review board to ensure equitable access to LT for patients with PSC and bacterial cholangitis[98].

Sex-based disparities in organ transplantation are also a concern.The MELD score, which relies on creatinine levels, underestimates true renal function in females due to lower muscle mass.Additionally, men face an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, which can lead to MELD exceptions[95].A analysis of waitlisted candidates from the scientific registry for transplant recipients showed that Hispanics with MELD scores < 20 had an 8% lower deceased donor liver transplant (DDLT) rate compared to Whites[99].Asian patients with MELD score < 15, on the other hand, had a 24% higher DDLT rate compared to Whites, but this rate dropped by 46% for Asian patients with MELD scores between 30-40 compared to Whites[99].As the field of LT continues to evolve, addressing ethical concerns requires filling knowledgegaps with robust and carefully gathered data that go beyond the informed consent of donors[95].

Table 4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients with cholangiocarcinoma being considered for Model For End Stage Liver Disease exception points

Table 5 Role of multidisciplinary team involved in the process of liver transplantation

Outcomes of liver transplant in patients with PSC: The one-year and five-year survival rates were better in patients with LT for impaired quality of life (97.4% and 94.9%) as compared to patients with LT for end-stage liver disease (91.4% and 88.6% respectively) based on a retrospective study on 74 patients with LT[100].The one-year and five-year survival rates for patients with suspicion of neoplasia prior to the LT were 95.8% and 74.1% respectively[100].A larger study of 6071 patients had similar outcomes with patient survival rate of 89.7%, 79.8%, 70.7%, 58.3%, 43.8% and 20.4% respectively at 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 years respectively[101].Based on a study of 6911 LT patients from the OPTN database, the unadjusted survival rate was significantly higher among the LDLT group as compared to the DDLT group[102].The most common factors associated with death after LT were infections, malignancies, cardiovascular diseases, graft failure (GF) due to rejection, and hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT)[101,103,104].

Patients with LT for PSC have an acute cellular rejection (ACR) rate of 20-40%, requiring additional immunosuppression[105].ACR does not affect long-term graft or survival outcomes in patients with LT, as opposed to patients with renal transplant[105].A retrospective study of patients with a diagnosis of PSC (24 patients) and PSC-autoimmune hepatitis overlap (2 patients) without evidence of CCA at the time of LDLT showed allograft rejection successfully managed by immunosuppression in 11.5% patients, postoperative bile leak in 7.6% patients managed conservatively, and biliary stricture in 11.5% patients with successful ERCP and biliary stent placement[103].Biliary strictures and bile leaks are other common complications after LT with an incidence of 5%-15% in patients who received DDLT and 28%-32% in recipients of right lobe LDLT[106].The mean time interval for presentation of biliary strictures after LT is 5-8 mo[106].Biliary strictures are classified into anastomotic variant and non-anastomotic (NAS) variant.NAS variants may be caused due to HAT and non-HAT etiologies like chronic ductopenic rejection, ABO incompatibility, PSC causing recurrent or ischemic strictures, age of the donors, duration of use of vasopressors, prolonged cold and warm ischemia times, preservative injury, and donation after cardiac deaths[106].NAS variants related to ischemia usually present within one year and those related to immunological factors present after one year of LT[107].

A study based on the review of 22 publications with a total of 1399 patients who underwent LT for PSC showed that the recurrence rate of PSC was around 18.5%, ranging from 5.7%-59.1%[108].Another study with a patient population of 230 had a recurrence rate of 23.5% with a median of 4.6 years after LT[108].Some of the most common factors related to an increased risk of recurrence of PSC are presence of HLA-DRB1*08 in the donor or recipient, absence of donor HLA DR52, older and younger recipients, male recipients, development of UC after LT, requirement of a longer duration of maintenance therapy with steroids (> 3 mo), steroid resistant ACR, and the presence of CCA or concurrent infection with cytomegalovirus in the donor[108].Due to a high recurrence rate of PSC in patients and a 4-fold increase in the risk of GF or mortality within 5 years of LT; liver re-transplant (ReLT) is considered to extend survival[109].

Quality of life and psychological outcomes after liver transplant: The health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and employment after LT depends on the etiology of the ESLD.In a cross-sectional study of 356 patients post LT, the return to employment rates within six months were highest amongst patients with PSC (2.4 times) and alcoholic cirrhosis (2.5 times) as compared to patients with primary biliary cirrhosis.However, post LT HRQOL was comparable among different ESLD etiologies[110].Early retirement was also significantly higher, reaching 83% in patients with PSC[110].Most commonly reported symptoms of physical distress after LT were fatigue, muscle weakness, increased appetite, headache, backache, and bruising which were higher in females over one year as compared to men[111].The most commonly reported symptoms of psychological distress at one year were sleeplessness and mood swings, followed by nervousness, depression, and difficulty concentrating[111].Recipients of LT rated their overall health as 7.17 ± 2.22 out of a possible score of 10 based on a questionnaire adapted from Karnofsky functional performance scale, medical outcomes study short form (SF-36), and psychosocial adjustment to illness scale, with 10 being the best outcome[112].The greatest benefit reported post LT was “being alive”.The worst factor reported about being a LT recipient was dependence on medications and the cost of insurance and medications[112].

Future directions in management of PSC: Recent advancement in digital technology have opened up new possibilities of enhancing the understanding of liver anatomy and vascular structures through the creation of three-dimensional (3D) liver models using data from computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans[113].PSC often involves the development of strictures and narrowing of the bile ducts, making LT surgery more challenging[114].The emerging technique of 3D liver transplant offers surgeons assistance in planning surgical procedures, including precise identification of blood vessels and bile ducts, improving the accuracy and efficiency of transplant surgeries[115,116].

Stem cell therapy and gene therapy represent two emerging treatments with potential for managing PSC.Stem cell therapy involves using stem cells to repair and regenerate damaged liver tissue[117].Various types of stem cells , such as mesenchymal stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, and embryonic stem cells, have been investigated for their potential in treating liver diseases, including PSC.Studies indicate that stem cell therapy may reduce inflammation and promote tissue regeneration in PSC cases[117,118].Gene therapy, on the other hand, utilizes genes to modify the expression of specific proteins involved in the development and progression of the disease.One potential target for gene therapy in PSC is the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, which plays a role in liver inflammation regulation.Inhibiting the NF-κB pathway has shown promise in reducing inflammation and fibrosis in PSC[119].Despite the potential benefits of stem cell and gene therapies in PSC, further research is needed to determine their safety and efficacy.Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the use of these therapies in PSC treatment, and their outcomes will determine their future role in managing the disease[117].

CONCLUSION

LT plays a very crucial role in the management of patients with PSC due to limited options and studies on outcomes with medical management.This review offers a summary of clinical features, diagnosis, medical management and a detailed discussion on the indications, clinical and psychosocial outcomes, ethical dilemmas, and future aspects in the field of liver transplant for management of PSC.The review also highlights the important aspect of pReLT psychosocial evaluation, as well as psychosocial outcomes post-transplant, which plays a pivotal role in preventing mental health crises in the patients.Significant efforts need to be directed towards addressing the ethical issues in liver transplant for equity of the care.Patients with PSC will also greatly benefit from more advances in the medical management of PSC.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Shah YR, Nombera-Aznaran N, Ali H, and Dahiya DS contributed to conception and design; Shah YR, and Dahiya DS contributed to administrative support; Shah YR, Nombera-Aznaran N, Ali H, and Dahiya DS contributed to provision, collection, and assembly of data; Shah YR, Guevara-Lazo D, Calderon-Martinez E, Nombera-Aznaran N, Tiwari A, Kanumilli S, and Dahiya DS contributed to review of literature and drafting the manuscript; Shah YR, Dahiya DS, Shah P, Pinnam BSM, and Ali H contributed to revision of key components of the manuscript and final approval of manuscript; Shah YR, Guevara-Lazo D, Calderon-Martinez E, Nombera-Aznaran N, Tiwari A, Kanumilli S, Shah P, Pinnam BSM, Ali H and Dahiya DS are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial.See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin: United States

ORCID number: Purva Shah 0000-0001-5516-3411; Hassam Ali 0000-0001-5546-9197; Dushyant Singh Dahiya 0000-0002-8544-9039.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Gastroenterology; American Gastroenterological Association; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

S-Editor: Qu XL

L-Editor: A

P-Editor: Cai YX

World Journal of Hepatology2023年8期

World Journal of Hepatology2023年8期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Emerging therapeutic options for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review

- Stages of care for patients with chronic hepatitis C at a hospital in southern Brazil

- Tenofovir alafenamide significantly increased serum lipid levels compared with entecavir therapy in chronic hepatitis B virus patients

- Prognostic and diagnostic scoring models in acute alcohol-associated hepatitis: A review comparing the performance of different scoring systems

- Impact renaming non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to metabolic associated fatty liver disease in prevalence, characteristics and risk factors