Ecological correlates of sport and exercise participation among Thai adolescents:A hierarchical examination of a cross-sectional population survey

Areekul Amornsriwatanakul,Leanne Lester ,Fiona C.Bull ,Mihael Rosenerg

a College of Sports Science and Technology,Mahidol University,999 Phutthamonthon Sai 4 Salaya,Phutthamonthon District,Nakhon Pathom 73170,Thailand

b School of Human Sciences(Exercise and Sport Science),The University of Western Australia,35 Stirling Highway,Nedlands,Perth,WA 6009,Australia

c Centre for Built Environment and Health,School of Human Sciences,The University of Western Australia,35 Stirling Highway,Nedlands,Perth,WA 6009,Australia

Abstract Background:Understanding factors influencing adolescents’sport/exercise participation(S/EP)is vital to developing effective interventions,but currently,evidence from less developed countries is limited.The purpose of this study was to examine correlates of S/EP across individual,interpersonal,and environmental levels in a nationally representative sample of Thai adolescents.Methods:Data from 4617 Thai adolescents aged 14-17 years old were obtained from recruited schools across Thailand.Data on S/EP(outcome variable),and psychosocial,home,and community environment covariates were collected from individual adolescents using the Thailand Physical Activity Children Survey,Student Questionnaire.School environmental data were collected at the school level using a School Built Environment Audit.Hierarchical regressions taking into account school clustering effects were applied for data analysis.Results:At the individual level,age and body mass index were independently and strongly correlated with S/EP.Adolescents with high preference for physical activity (PA) (odd ratio (OR)=1.71, p <0.001) and at least a moderate level of self-efficacy (OR=1.33, p=0.001) were more likely to have high S/EP.At the interpersonal level,adolescents whose parents joined their sports/exercise at least 1-2 times/week(OR=1.36, p=0.003) received -3 types of parental support (OR=1.43, p=0.005) and who received siblings’ (OR=1.26, p=0.004) and friends’(OR=1.99,p<0.001)support had a greater chance of high S/EP.At the environmental level,adolescents’S/EP was greater when there were at least 3-4 pieces of home sport/exercise equipment(OR=2.77,p=0.003),grass areas at school(OR=1.56,p<0.001),and at least 1-2 PA facilities in the community(OR=1.30,p=0.009).Conclusion: Multiple factors at different levels within an ecological framework influencing Thai adolescents’ S/EP were generally similar to those found in developed countries,despite some differences.For those interested in promoting and supporting Thai adolescents’engagement in sports/exercise,further exploration of the influence of self-efficacy and attitude toward PA is required at the individual level;parental and peer support at the interpersonal level;and home sport equipment,school grass areas,and neighborhood PA facilities at the environment level.

Keywords: National survey;Noncommunicable diseases;Physical activity;Policy;Thailand youth

1.Introduction

Physical inactivity is a leading cause of noncommunicable diseases and mortality globally.1Adolescent participation in physical activity (PA),especially structured activities like sports and exercise,tracks into adult PA and may reduce the incidence of some noncommunicable diseases.2,3However,among adolescents,sedentary behavior and insufficient PA levels are high,and both constitute a global public health concern.4Participation in sports and exercise is significantly associated with an increased probability of adolescents’ accumulating PA of 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) daily,as recommended by the World Health Organization.5,6In Thailand,recent studies reported that in 2015 the prevalence of sufficient PA in adolescents aged 14-17 years was low (20%),7although almost half(44%) had participated in organized sports at least once a year,and 57% had engaged in -3 sport activities in the past week.8Similarly,the Thailand National Statistical Office reported that 21% of adolescents and young adults (aged 15-24 years) had participated in 3-4 days/week of moderate or vigorous sports/exercise or recreational activities.9Understanding the factors influencing Thai adolescents’ sport/exercise participation (S/EP) will help to explain the prevalence of low PA levels in this population and facilitate the development of effective interventions to increase PA,particularly through involvement in sport and exercise.

Adolescents’ S/EP can be influenced by a wide range of individual,interpersonal,and environmental factors,commonly framed as an “ecological framework”.10This ecological framework overcomes several limitations of individually based behavioral and psychosocial theories and incorporates a wide range of influences at multiple levels,specifically adding intrapersonal and environmental factors.10The present study was based on the adapted ecological framework proposed by Bauman et al.,11a more recent concept encompassing factors ranging from individual to global.These factors interact across different levels and influence a specific health behavior such as S/EP.

At the individual level,systematic reviews suggest that gender and age are consistent correlates of PA participation in adolescents.11-13Results from studies of the relationship between body mass index(BMI)and adolescents’PA have been inconsistent,with some studies suggesting no relationship5,11,12,14and others suggesting a negative relationship.15-17Time spent using screen devices (mostly TV watching) and doing other sedentary activities also have been shown to have an inconsistent relationship with adolescents’PA.12,18-22Individual-level variables associated with PA in adolescents also include psychological factors.Self-efficacy and attitude toward PA have a positive association,11,13,23-25whereas other psychological factors,including perceived PA benefits,outcome expectations,and perceived barriers,have an inconsistent relationship.12,24,26

At the interpersonal level,parental support in various forms(e.g.,encouragement and facilitation)has been shown to correlate positively with adolescents’ PA.12,13,27-29Parents’ direct involvement in their children’s activities also correlates with increased PA participation among adolescents,22,28,30,31whereas the literature has shown that parents’PA level has no correlation with their children’s PA.11,12,22,26In addition to parental support,support from siblings and friends can positively influence adolescents’PA participation.12,23,25,28,32-34

At the environmental level,studies of home environments suggest that availability of sport/exercise equipment12,22,26,35,36and play space at home36do not have any relationship with PA.In a wider context,the school environment has received greater attention,with some studies finding that adolescents spent the greatest amount of MVPA time on grass areas compared to other types of areas.37To date,it has been found that only certain types and locations of sport facilities (e.g.,indoor gymnasiums and football fields) are consistently associated with adolescents’ PA,whereas the number of PA facilities and access to sports equipment are not.25,38-40Certain aspects of the neighborhood environment can also influence adolescents’ PA;previous studies have suggested that availability of PA facilities and programs in the neighborhood are positively associated with adolescents’ PA,13,22,35whereas community safety is not.26,35,41

Much of the evidence to date is drawn from developed countries11,24,26where cultural and social contexts (including resources) might be different from those in less developed countries.Although there is a growing evidence base from these less developed countries (mostly from Brazil and China),11there is only limited evidence from studies conducted in Thailand and other Asian countries that have reported results from a population-representative sample with a particular focus on S/EP among adolescents.A recent review reported that only a small proportion (15.7%) of studies conducted in Thailand used adolescents as participants and suggested that additional studies using population-representative samples are needed.42Additionally,the evidence is particularly scant from studies that have applied an ecological framework encompassing larger-scale factors and less recognized environmental influences.More important,we cannot assume that the correlates of S/EP or the strength of associations would be similar to those found in developed countries.Although the prevalence of Thai adolescents who meet the World Health Organization PA guidelines is consistent with the global estimate of 20%,this percentage is lower than in countries that have more resources43(e.g.,the United States,where the percentage is 27%44).This warrants an exploration of potentially influential correlates,especially environmental correlates.Therefore,the purpose of this study was to examine correlates of S/EP across individual,interpersonal,and environmental levels in a nationally representative sample of Thai adolescents aged 14-17 years.Based on previous literature,it was hypothesized that the examined individual,interpersonal,and environmental variables would be correlates of S/EP among Thai adolescents.

2.Methods

2.1.Participants

Participants in this study were 4617 adolescents aged 14-17 years old.Data were obtained from the Thailand Children Physical Activity Survey (TPACS),a cross-sectional study in a nationally representative sample of more than 16,000 children and adolescents aged 6-17 years.The participants were recruited through a multistage,stratified cluster sampling from 28 provinces in 9 regions across the country,including Bangkok.Children aged <14 years were excluded from this present study because no duration data (time spent doing sports/exercise) were available.The participants aged 14-17 years completed the self-administered survey in a classroom setting,following a standard data-collection protocol and assisted by 3 trained research staff and a class teacher.Weights and heights of participants were objectively measured by a research staff at the time that participants completed the survey.Data were collected concurrently in all geographical areas during the period from June to August 2015.Data from the completed surveys were entered twice and manually checked by a trained group of research staff against hard copies to rectify discrepancies.Final datasets from each area were centrally collated and systematically cleaned.Further information about TPACS,the sampling conducted at each stage,and data collection protocol is provided in detail elsewhere.7

TPACS received ethical approval from the Institution for the Development of Human Research Protections in Thailand and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia (RA/4/1/7335).The survey adopted active school and passive parental consent,both of which were approved by the Institution for the Development of Human Research Protections and Human Research Ethics Committee.Because schools and school principals are considered guardians of students,the recruitment method used was the active school participation,which is commonly used in Thailand for research in children.After the school principal approved of and provided written consent for the study,it was then conducted.Most students agreed to participate.Students were provided with an information sheet for themselves and another information sheet for their parents.Students were asked to deliver the information sheets to their parents and inform them of the student’s potential participation in the survey.On the day of the data collection,before the survey took place,research staff asked the students to ensure that they had informed their parents before completing the survey.In taking the survey,students were provided with an opportunity to decline or withdraw their participation at any time.Staff administering the survey noted whether any participants declined or withdrew.

2.2.Measures

The Student Questionnaires (TPACS-SQ) version for adolescents aged 14-17 years was used to collect data on the adolescents’ participation in different PA domains,including sports/exercise and sedentary behaviors.Sociodemographic,social,psychological,and home and community environmental data were also collected.The questionnaire,which measures adolescents’participation in sports and exercise,was developed based on a previously validated instrument45that was significantly correlated with accelerometer data (r=0.40,p<0.001)46and had fair reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.34-0.85,Cohen k=0.15-1.00,percent agreement=33.3%-100%).The psychological measures,including attitude toward PA,expected outcomes,and self-efficacy,used in the TPACS-SQ were taken from a previously validated questionnaire called the Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey,an adjusted version of Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey used among Chinese-Australian adolescents.The original items provided acceptable reliability(4 of 9 factors with intraclass correlation coefficient -0.6) and predictive validity.47The questionnaires in the interpersonal attribute section have acceptable reliability.The Cohen k values for parents’coparticipation,sibling support,and friend support were 0.60 (p<0.001),0.45 (p<0.002),and 0.78 (p<0.001),respectively,whereas the Cohen k value for types of parental support ranged from 0.30 to 0.79.

School physical environmental data were collected from the 334 schools that participated in the student survey.Trained staff administered the survey using the School Built Environment Audit Form (TPACS-BEA).The TPACS-BEA was developed based on a previously tested audit tool called the Physical Activity School Scan.48Face validity was conducted for development of the original items used in the Physical Activity School Scan.The majority(90%)of intrarater correlations of the original items were above 0.70,reflecting moderate reliability,whereas 80% of interrater correlations provided good to excellent reliability.49Face validity was also employed for the TPACS-BEA by circulating the audit form to experts for their review.The improved audit was then pilottested by field staff.Feedback from the experts and field staff was used to improve the audit procedure and instructions.The TPACS-BEA had high interrater reliability (Cohen k=0.88,p<0.001)49when tested by different staff at the same school on the same day.

After merging the data from TPACS-SQ with TPACS-BEA and removing children who were younger than 14 years old,the participants included in this study were clustered within 124 schools where a high school level of education was offered.

2.2.1.Measurement of sport participation

Adolescents were provided with a list of possible sports/exercise activities and asked about the frequency and total amount of time (min) they had spent in each activity over the past 7 days.S/EP was calculated using the metabolic equivalent (MET),which is a measure of energy expenditure,where 1 MET equals 1 kcal/kg/h.50The intensity level of each activity was expressed as METs minute per day,which was derived from corrected METs multiplied by total minutes spent in the activities per day.The corrected METs were obtained from the MET value of each activity assigned,according to the updated compendium of PA50and age and BMI,adjusted by the resting metabolic rate for children.51Despite the potential limitations of categorizing continuous data,we chose to convert METs into low and high S/EP for the purposes of this study.Therefore,the total METs min per day summed across all activities was calculated separately for boys and girls and then merged into a unisex outcome variable dichotomized into low and high by using the median(164.24 METs min/day)as a cut-point.

2.2.2.Measurement of adolescents’individual variables

BMI,derived from weight(kg)divided by height squared(m2),was classified into Underweight,Normal,Overweight,and Obese by using the unofficial Asian BMI cut-offs for international children.52Screen time and sitting-down activities were assessed by asking the participants if they did any screen time or sitting-down activities(examples were provided in a list)over the past 7 days.If they did any screen time or sitting-down activities,they were required to provide additional data on the frequency and total amount of time (min) spent in those activities.The time spent across all activities per day was calculated and dichotomized into “-120 min/day” and “>120 min/day” according to the screen-time guidelines.53

2.2.3.Measurement of psychological characteristics

All psychological characteristics were assessed by asking how much participants agreed with a list of statements under each construct.A 5-point Likert scale was provided for all statements (1=strongly disagreeto 5=strongly agree,with 9=don’t know).For social parental support,participants were asked if,for example,their parents helped them to be physically active.To assess parental PA,participants were asked if their parents did a lot of PA.Family education beliefs were evaluated by asking participants if their parents thought education was more important than PA.In order to assess their perceived barriers,a list of possible barriers,e.g.,no sports equipment and no facilities,was provided,and participants were asked how much they agreed with each of the barriers.To assess their perceived ailments,they were asked how much they agreed with a list of possible injuries or health problems that might have impacted their PA.PA preferences and attitudes were assessed by asking the participants if,for instance,they liked PA or preferred to watch TV.Personal benefits of PA were assessed by asking participants about their perception of benefits provided by PA.Positive and negative outcome expectations were assessed by asking participants if they thought,for example,that PA helped them study better (positive)or prevented them from doing things they preferred to do(negative).To evaluate self-efficacy,participants were asked about their confidence in doing PA in specific situations (e.g.,being physically active most days after school).Response options for this construct ranged from 1=“I’m sure I cannot” to 5=“I’m sure I can”.The sum of the scores for each psychological construct were categorized into 3 groups using the following percentiles: Low (-25th percentile),Moderate(26th-75th percentile),and High (>75th percentile),except for parental PA,which was dichotomized into Low and High using the 50th percentile.

2.2.4.Measurement of interpersonal attributes

Parents’coparticipation was assessed by asking participants how often their parents or guardians played sports or exercised with participants.Their responses were classified into the following categories: none/rarely,1-2 times/week,and-3 times/week.Types of parental support were assessed by asking participants if their parents encouraged them to play sports or exercise.If the answer was yes,a list of potential types of support was provided,and the data were classified into:none,1-2 types,and -3 types.Friend or sibling support was assessed by asking participants whether their siblings or friends encouraged them to be physically active.Yes/No response options were offered.

2.2.5.Measurement of environmental variables

Data on play space at home,home sport/exercise equipment,community PA facilities,community sport programs,and community safety were derived from the TPACS-SQ.Data on the schools’ indoor gymnasiums,outdoor concrete areas,grass areas,sports-ground facilities,access to sports equipment,and shower rooms were derived from TPACSBEA.Availability of play space at home was assessed by asking participants where they usually played at home,and their responses were collapsed into yes or no classifications.Availability of sports/exercise equipment at home was assessed by providing a list of sports/exercise equipment,and participants were asked if they had any of them at home(Yes/No).Responses were classified into: none,1-2 pieces,3-4 pieces,and -5 pieces.Availability of community PA facilities was assessed by using a similar approach,and responses were classified into the following categories: none,1-2 facilities,and -3 facilities.Availability of community sports programs was assessed by recording each participant’s response to the following statement: “My community regularly organizes activities related to PA,exercise,and sports.” Community safety was assessed by recording each participant’s response to this statement:“It is safe enough for me to play in my neighborhood during the day.” For both the community sports programs and community safety statements,participants’response options ranged from 1=totally disagreeto 5=totally agree.Their answers were collapsed into a yes or no classification(3,or neutral,was handled as a no).The availability of the schools’ indoor gymnasiums,outdoor concrete areas,grass areas,and shower rooms was inspected by our research staff if these facilities were available at the participating schools.Sports ground facilities were assessed by computing the total number of facilities available and were categorized into 3 groups: 1-3,4-6,and -7 facilities.Access to sports equipment was categorized into None,Difficult,and Easy.Yes/No were available options for grass areas and shower rooms.

2.3.Data analysis

The original 5536 cases drawn from the TPACS were checked for eligibility and for missing data on any variables.Eventually,a total of 4617 cases (83.4%) remained for analysis and were weighted against age,sex,and regional distributions provided by the Ministry of Education in Thailand.54Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe sample characteristics,and x2tests andttests were performed to examine gender differences in the sample characteristics.The present study aimed to explore correlates of S/EP across different ecological levels,so hierarchical modeling was applied with 2 main steps,based on analytical strategies suggested by Victora et al.55and previous studies.56At the first step,all potential variables were examined individually using a univariable logistic regression.Variables significantly correlated with the outcome variable atp<0.01 in the first step were eligible to be included in the second step,and this inclusion criterion was applied for subsequent development of the hierarchical regression models.All variables were classified into 4 groups: (1)individual characteristics,(2)psychological attributes(this set of variables was separated from the first one to make a clear distinction),(3)interpersonal variables,and(4)environmental variables.Before developing the hierarchical models in the second step,the multicollinearity of all covariates was evaluated,and none was found.Based on the ecological framework,4 multivariable regression models were sequentially constructed: (1) an individual variable model;(2) a set of psychological variables that were added into Model 1 to generate Model 2;(3)a set of interpersonal variables that were added into Model 2 to create Model 3;and (4) environmental variables that were added into Model 3 to create Model 4.Only variables identified as significant in each model would remain in the subsequent analysis.This order of entry for each set of variables started from individual and extended to environmental,according to the ecological framework,which assumes that multiple factors at multiple levels influence behavior from the proximal factors to the more distal factors.All regression models took into account the school-clustering effect because students were nested within school-level data,and all models used robust standard errors to obtain unbiased standard errors.The log likelihood ratio test was conducted to examine the model fit.The descriptive statistics and x2tests were performed in SPSS Statistics for Windows,Version 23(IBM,Armonk,NY,USA),and all regressions were conducted in STATA Version 12(StataCorp.,College Station,TX,USA).

3.Results

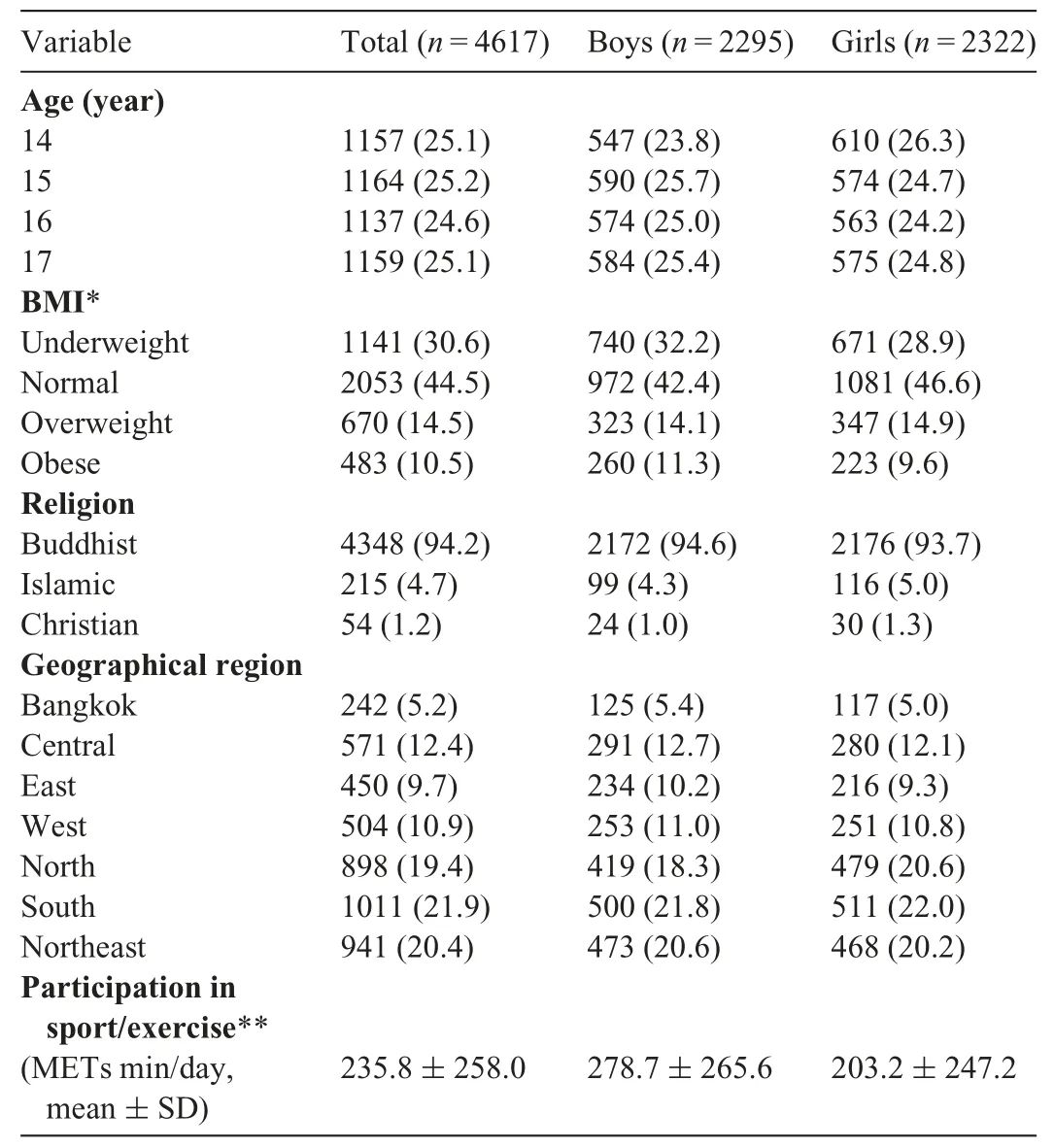

The descriptive statistics regarding survey respondents(sex,age,BMI,religion,geographical region,and participation in sports/exercise) are presented in Table 1.The proportion of boys(49.7%)and girls(50.3%)participating in the survey was similar,and no significant difference between genders was found by age,religion,or geographical region (allp>0.05).A significantly greater proportion of girls were within the normal BMI category than were boys (x2=12.70,p=0.005),and boys recorded higher METs min per day than did girls(t(4,615)=9.95,p<0.001).

Table 1Characteristics of the samples.

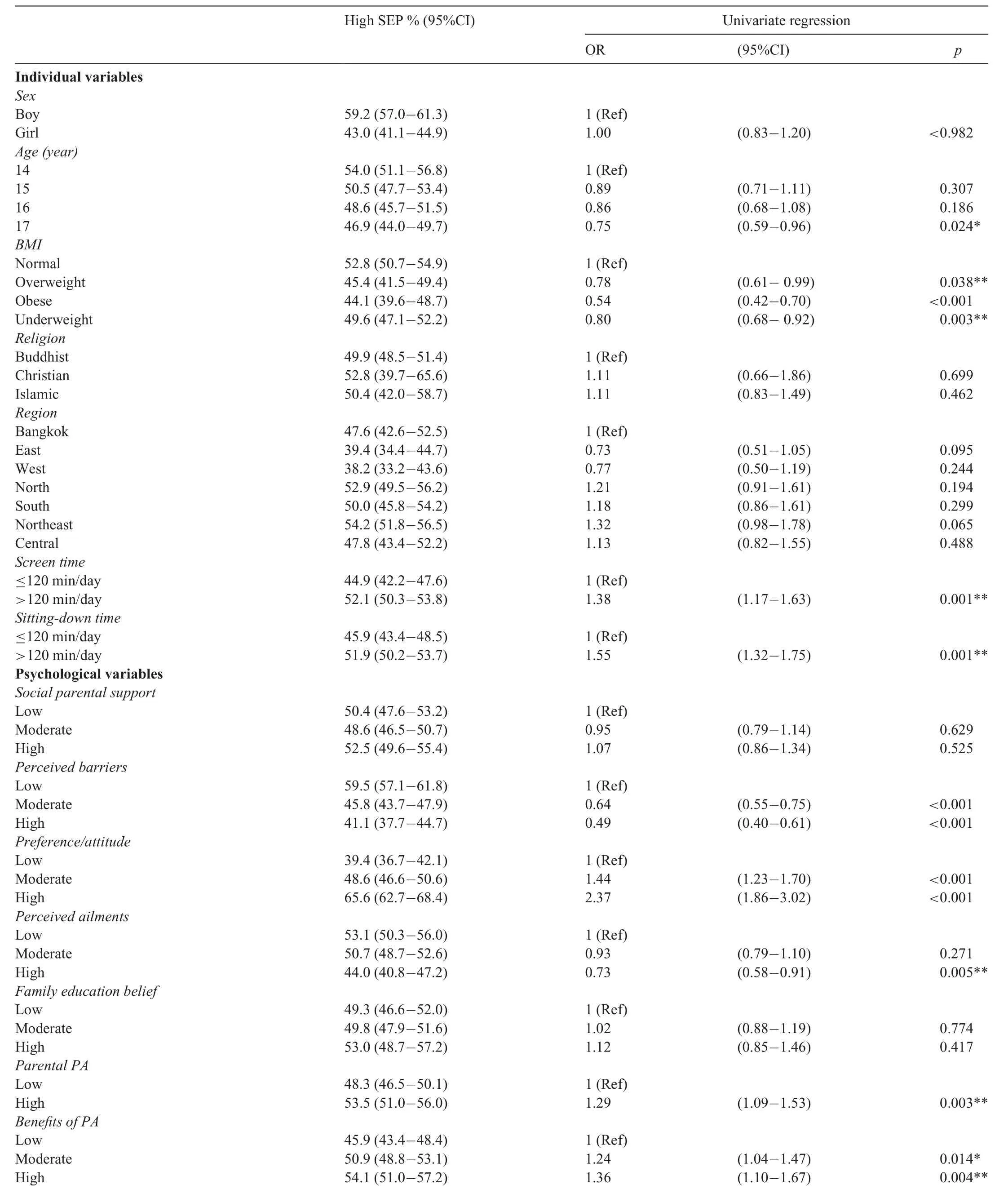

Univariable regressions (Table 2) revealed that 22 of the 32 variables across individual,interpersonal,and environment levels had significant correlations with high S/EP in adolescents.Religion (p=0.722),parental support (p=0.367),family education belief(p=0.720),school indoor gymnasiums(p=0.952),school outdoor concrete areas(p=0.697),school sports ground facilities(p=0.057),access to sports equipment (p=0.388),and change/shower rooms (p=0.994) were not significantly correlated with high S/EP and were excluded from the second step of analysis.Community safety (p=0.012) was significantly correlated with the outcome variable but was greater than the setpvalue(0.01)and was therefore excluded from Step 2.Exceptions were made for sex and age because the literature suggests that they are consistent correlates of PA.

Table 2Univariable regression of correlates of sports/exercise participation among Thai adolescents.

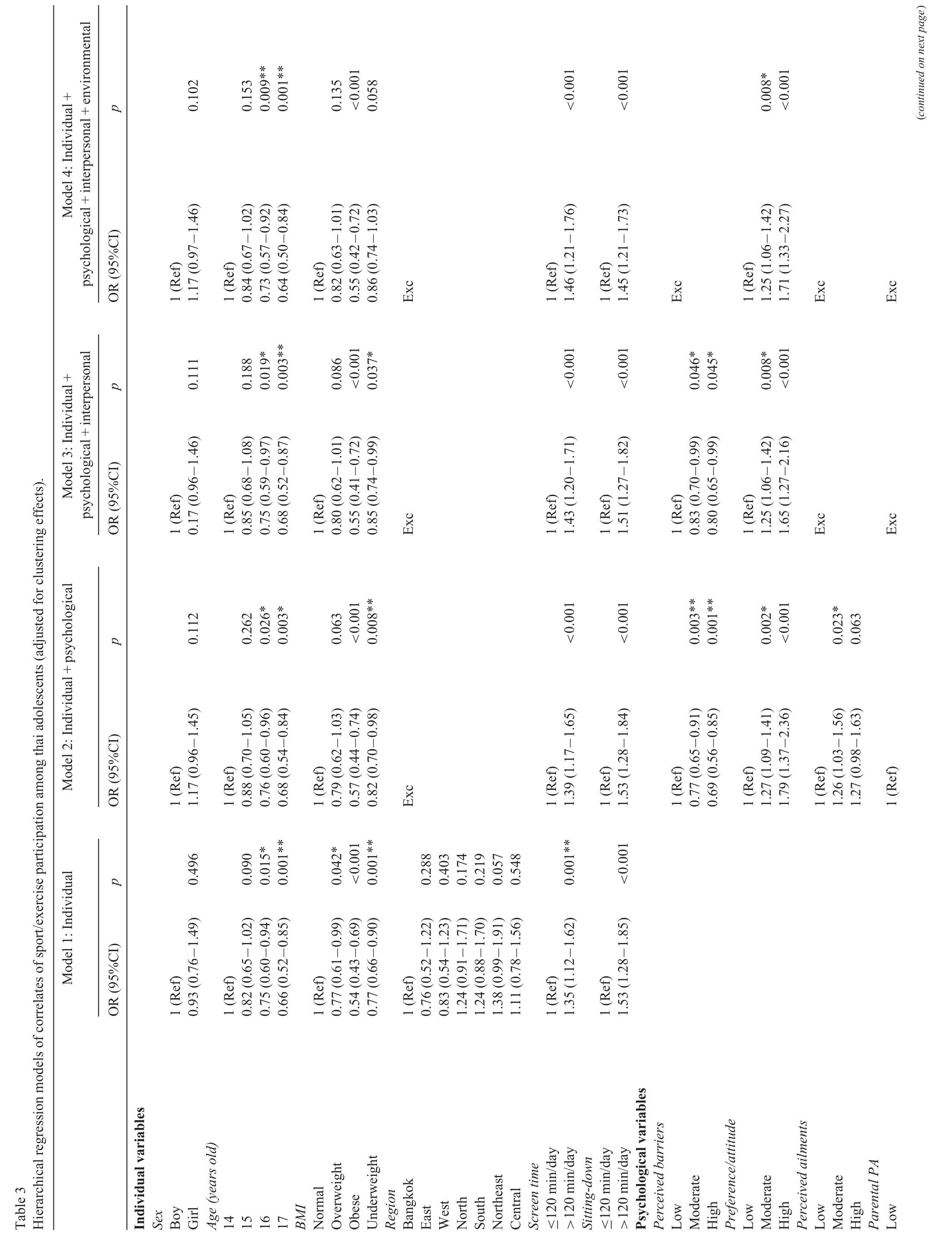

Results of the hierarchical regressions are presented in Table 3.At the individual level,adolescents aged 16 and 17 years were associated with reduced odds of greater S/EP(16 years: odd ratio (OR)=0.73,p=0.009;17 years:OR=0.64,p=0.001) compared with adolescents aged 14 years.Compared with adolescents with normal weight,obese adolescents were associated with reduced odds of high S/EP (OR=0.55,p<0.001).More time spent on screen devices (OR=1.46,p<0.001) and sitting-down activities(OR=1.45,p<0.001) were positively associated with increased odds of high S/EP.The odds of having high S/EP increased by 71% (OR=1.71,p<0.001) in adolescents who had high preferences for sports/exercise compared with those who had low preferences.Similarly,adolescents who had moderate self-efficacy had increased odds of having high S/EP compared with those who had low self-efficacy (OR=1.33,p=0.001).The odds of having high S/EP more than doubled(OR=2.08,p<0.001) among those who had high self-efficacy.Conversely,adolescents who had high levels of negative-outcome expectations reported reduced odds of engaging in sports/exercise compared with their counterparts who had low negative-outcome expectations(OR=0.63,p=0.001).

At the interpersonal level,adolescents who reported that their parents played sports or exercised with them 1-2 times/week had increased odds of high S/EP(OR=1.36,p=0.003)compared with those who reported no parent coparticipation.The odds increased to almost 70% (OR=1.68,p=0.001) when parents joined their sport/exercise activities -3 time/week.Adolescents who reported receiving -3 types of parental support reported increased odds of high S/EP (OR=1.43,p=0.005) compared with those who received no support.Furthermore,when there was support from sibling and friends,adolescents had higher odds of engaging in greater S/EP (OR=1.26,p=0.004 and OR=1.99,p<0.001,respectively).

At the environmental level,the availability of 3-4 pieces of home sport/exercise equipment was strongly associated with greater odds of having high S/EP among Thai adolescents(OR=2.77,p=0.003).The odds increased to 233%(OR=3.33,p<0.001) when there were -5 pieces of sport/exercise equipment.The availability of 1-2 PA facilities in the community was also positively associated with greater odds(OR=1.30,p=0.009)of high S/EP,with the odds rising to almost 80%(OR=1.77p<0.001)when there were -3 PA facilities in the community.When schools had grass areas,adolescents had increased odds of greater S/EP (OR=1.56,p<0.001).The log likelihood ratio test showed that the 4 developed models fit well because residuals of variance decreased significantly;all modelsp<0.001(Table 3).

4.Discussion

This study examined correlates of adolescents’ S/EP across individual,interpersonal,and environmental levels by using data from a nationally representative sample of an upper-middleincome country(Thailand).After adjusting for personal,interpersonal,and environmental factors influencing S/EP,screen and sitting time,parents’ coparticipation,and support from parents and peers,the amount of home sport/exercise equipment,school grass areas,and community PA facilities were the strongest positive correlates of S/EP by Thai adolescents.In addition,age and BMI remained independently significant correlates of S/EP.The results show some similarities but also reveal a number of differences compared to findings from developed countries.The positive associations of attitude toward PA,self-efficacy,parents’coparticipation,parental and peer support,school grass areas,and community PA facilities are similar to previously reported findings.12,13,22,23,27,28,30-33,37,41,57-60However,the results for home sport/exercise equipment and community sport programs differed in direction.12,13,22,26,35,36

As a biological factor,age remained independently and strongly correlated with S/EP in all models of analyses,whereas gender was no longer significant in the final model.S/EP decreased with age,and this finding is in line with the international literature.11,13,61BMI was another biological factor examined in the present study,and it showed an inverse relationship,which contrasted with the null association suggested by the literature,11but evidence from Asian countries supported our findings.15,62

Consistent with the literature,adolescents who anticipated negative consequences of playing sports and exercising were less likely to participate in these activities,whereas adolescents with positive attitudes toward PA had a greater probability of high S/EP.13The strong positive relationship between self-efficacy and greater S/EP found in our study of Thai adolescents was also consistent with findings from the international literature.11,13,23,24These positive psychological correlates should be examined further in intervention and longitudinal studies because potentially,they can contribute to the success of PA promotion among Thai adolescents.

Screen and sitting time were found to be positively correlated with S/EP in Thai adolescents.Our results are similar to some results of studies in Asian countries14,63and in the United States,64where adolescents simultaneously highly engaged in both sedentary behaviors and PA.Although counterintuitive,the literature suggests that the relationship between these 2 behaviors is more than a simple substitution of 1 for the other;they may coexist without detrimental effects on PA behaviors.18,20,65It is noteworthy that other studies have found particular types of sedentary activities,such as doing homework and sitting in a classroom,seem to have a positive relationship with PA behaviors,whereas other sedentary activities,such as watching TV,had no relationship.20To better understand the association between sedentary behaviors and S/EP in Thai adolescents,future research should seek to further clarify the association between different types of sedentary behaviors and S/EP.

All interpersonal factors were significantly associated with adolescents’ S/EP.Consistent with other studies,12,13,22,28our study found that parents have a substantial role in influencing Thai adolescents’ S/EP,and more parental support(either direct or indirect) was positively associated with adolescents’ being highly engaged in sports/exercise.Importantly,active involvement of parents in adolescents’sport/exercise activities,even at a minimal level (1-2 times/week),was associated with a higher level of S/EP.These results confirm findings in Western22,28,30and Asian countries.31Peer support (both siblings and friends)showed a strong positive association with high levels of S/EP among Thai adolescents.These results are in agreement with studies,mostly from developed countries,that suggest that peer support,especially friends,plays a critical role in encouraging adolescents to regularly engage in sports and exercise.23,29,66Interventions aimed at promoting or maintaining sports/exercise among Thai adolescents might be more beneficial if they focus not only on individual adolescents but also involve their family members and friends.Family-integrated or family-based interventions targeting parenting styles and skills,parents’ capability of providing support to their children,and parents’ active participation should be considered as researchers investigate the effectiveness of these kinds of interventions.67,68

Three environmental factors,1 related to the home (availability of home sport/exercise equipment),another related to the school(grass areas),and the third related to the community(PA facilities),were significantly correlated with adolescents’S/EP.The positive association found between the availability of home sport/exercise equipment and S/EP contrasted with previous studies that reported no association.12,22,26,35,36The literature suggests that the relationship between these 2 variables is difficult to find,especially when generalized measures of PA are applied.22Noticeably,the positive association identified in our study might be due to the particular type of PA(sports/exercise)being investigated.The lack of a relationship between play space at home and adolescents’ S/EP is in line with the international literature.36The lack of a relationship possibly occurs because the majority of MVPA occurs outside the home,and measures of the outcome variable are not typically specific to the home.33,35

It is interesting that we observed a strong significant relationship between school grass areas and high S/EP among Thai adolescents because grass areas are usually reported to be associated with low to moderate PA intensity,such as active play or recreation.59However,a positive association between school grass areas and MVPA has been found in other countries.37,58,59A study in Denmark found that adolescents spent more MVPA time on school grass areas compared with other types of schoolyards.37In Australia and Canada,green areas were found to be the location where the highest proportion of students engaged in PA,59and a larger amount of grass area per student was associated with a greater amount of class time MVPA.58The literature suggests that grass/green areas are used predominantly for sports by adolescents,especially males.69Thus,this is the probable explanation for the strong positive relationship identified between school grass areas and high S/EP in our study.More than 85% of Thai schools have some grass areas,so further investigation into the size of the grass areas and school policies on their use will be helpful in understanding their potential impact on adolescents’ S/EP.Additionally,other school facilities,including indoor gymnasiums,outdoor concrete areas,and sports grounds,as well as access to sports equipment,were not related to S/EP in our study.Although these school variables were dropped early in our analysis,it is worth discussing briefly because all of these school facilities usually are locations where some types of formal sports/exercise occur.Therefore,in our study it is possible that Thai adolescents engaged in informal types of sports/exercise rather than in formal types.Another possible explanation is that because we used school facility indexes to aggregate the number of PA facilities in schools,no association was likely to be detected.25,38,70Further examination of the types of sports/exercise (i.e.,formalvs.informal) that adolescents engage in,the locations where these sports/exercise occur,and the specific PA facilities available in schools is warranted in order to understand more about adolescents’sports/exercise behaviors.

Beyond the school environment,in our study the number of PA facilities available in the neighborhood had a positive correlation with S/EP in Thai adolescents,which is consistent with studies in other countries.13,22,41,60Therefore,a provision of PA infrastructure(e.g.,indoor/outdoor sports grounds or parks)may be helpful in encouraging adolescents to engage more in sports/exercise.In our study,the availability of community sport programs did not show any relationship with Thai adolescents’S/EP,although community sport programs have previously been shown to increase adolescents’ S/EP.13,22One possible explanation is that,in general,community sport programs are organized and competitive in nature,but older adolescents,particularly girls,change their preference to nonorganized and noncompetitive sports.71Another possible explanation is that sport/exercise activities among Thai adolescents do not depend primarily on community initiatives.Additional evidence regarding community sport programs in Thailand would be useful in explaining the inconsistency of these findings.

The results of our study should be considered in the context of its limitations.First,the cross-sectional design used in our study did not allow for a causal relationship;thus,interpretation of the results should be made with caution.Second,the selfreport instruments used to measure S/EP in adolescents may not have captured the exact details because recall ability and item misinterpretation are potential weaknesses of self-reported instruments.72Third,TPACS-SQ had only fair reliability overall,and some caution should be used when interpreting the interpersonal measures because validity information was not available.Fourth,the dichotomized outcome variable might lead to potential loss of sensitivity or granularity in the analysis(i.e.,differentiation of quantities of change,particularly in samples of participants who were close to the cut-off point).Finally,TPACS-SQ did not collect the socioeconomic data of the sampled adolescents;therefore,this variable was not included in the present study.Despite these limitations,this study has several strengths.First,we used a previously validated instrument that not only allowed for international comparisons but also allowed for culturally applicable examples of PA relevant to Thai adolescents.Second,we used a nationally representative sample that provided data that was generalizable to the overall population.Our study also incorporated multiple levels and domains of influence concurrently,which provide insights that can be applied in future intervention research.

5.Conclusion

This is the first study in Thailand to report on the correlates of S/EP in a nationally representative sample of Thai adolescents aged 14-17 years within a socioecological framework.Adolescent girls participated in sports/exercise less than their male counterparts.Multiple factors at individual,interpersonal,and environmental levels significantly influenced Thai adolescents’S/EP.Despite the sociocultural and economic-development differences in Thailand compared with developed countries,many significant factors are similar.It may be helpful to include attitudes toward PA,self-efficacy,parents’ coparticipation,parental and peer support,availability of home sports equipment,school grass areas,and community PA facilities in future promotional efforts aimed at increasing S/EP by Thai adolescents.Longitudinal research and intervention studies are needed in order to understand the causal relationship of these correlates to sport/exercise.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Thai Health Promotion Foundation for research funding.The foundation had no involvement in conducting this study or preparing the results for publication.The authors appreciate the Thailand Physical Activity Research Centre for its administrative and coordinating support.The lead author thanks the Office of the Basic Education Commission for its collaboration and institutional support.We are indebted to all regional coresearchers and their staffs for their assistance in collecting data.We are grateful to all school principals,teachers,and students who participated in this study.

Authors’contributions

AA conceived and designed the study,partially conducted the statistical analyses,interpreted the results,and drafted the manuscript;LL conducted the statistical analyses,provided critical feedback,and edited the manuscript;FCB and MR collectively conceived and designed the study,provided critical feedback,and edited the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2023年5期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2023年5期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- How to make the “jump” on understanding the importance of the intrinsic foot muscles for propulsion

- Public health research on physical activity and COVID-19:Progress and updated priorities

- Examining the intrinsic foot muscles’capacity to modulate plantar flexor gearing and ankle joint contributions to propulsion in vertical jumping

- Exploring overweight and obesity beyond body mass index:A body composition analysis in people with and without patellofemoral pain

- Machine-learning-based head impact subtyping based on the spectral densities of the measurable head kinematics

- The management of the long head of the biceps in rotator cuff repair:A comparative study of high vs.subpectoral tenodesis