Adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines in children with mental,behavioral,and developmental disorders:Data from the 2016-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health

Ning Pn,Li-Zi Lin,Gorg P.Nssis,Xin Wng,Xio-Xun Ou,Li Ci,Jin Jing,Qing Fng,Gung-Hui Dong*,Xiu-Hong Li,*

a Department of Maternal and Child Health,School of Public Health,Sun Yat-sen University,Guangzhou 510080,China

b Guangdong Provincial Engineering Technology Research Center of Environmental Pollution and Health Risk Assessment,Department of Occupational and Environmental Health,School of Public Health,Sun Yat-sen University,Guangzhou 510080,China

c Physical Education Department,College of Education(CEDU),United Arab Emirates University,Al Ain 15551,United Arab Emirates

d Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics,SDU Sport and Health Sciences Cluster(SHSC),University of Southern Denmark,Odense 5230,Denmark

e Department of Fitness Surveillance Centre,China Institute of Sport Science,Beijing 100061,China

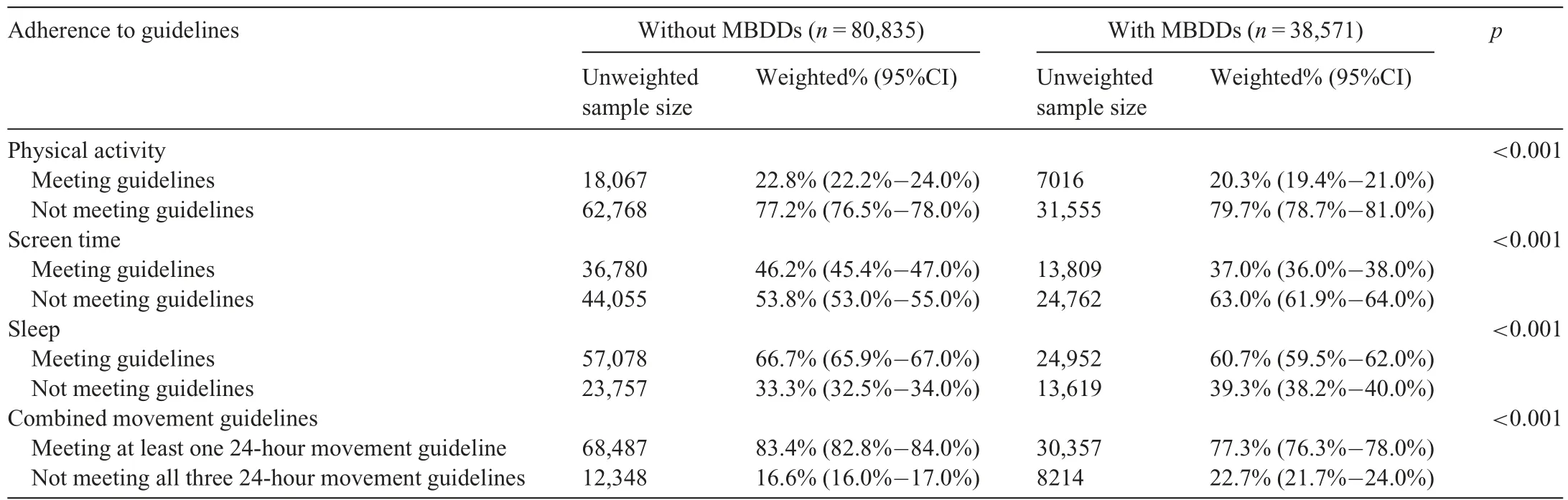

Abstract Background: Adopting a healthy lifestyle during childhood could improve physical and mental health outcomes in adulthood and reduce relevant disease burdens.However,the lifestyles of children with mental,behavioral,and developmental disorders (MBDDs) remains under-described within the literature of public health field.This study aimed to examine adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines among children with MBDDs compared to population norms and whether these differences are affected by demographic characteristics.Methods: Data were from the 2016-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health—A national,population-based,cross-sectional study.We used the data of 119,406 children aged 6-17 years,which included 38,571 participants with at least 1 MBDD and 80,835 without.Adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines was measured using parent-reported physical activity,screen time,and sleep duration.Results: Among children with MBDDs,20.3%,37.0%,60.7%,and 77.3% met the physical activity,screen time,sleep,and at least 1 of the 24-hour movement guidelines.These rates were lower than those in children without MBDDs(22.8%,46.2%,66.7%,and 83.4%,respectively;all p <0.001).Children with MBDDs were less likely to meet these guidelines (odds ratio (OR)=1.21,95% confidence interval (95%CI):1.13-1.30;OR=1.37,95%CI:1.29-1.45;OR=1.29,95%CI:1.21-1.37;OR=1.45,95%CI:1.35-1.56)than children without MBDDs.Children with emotional disorders had the highest odds of not meeting these guidelines (OR=1.43,95%CI: 1.29-1.57;OR=1.48,95%CI:1.37-1.60;OR=1.49,95%CI:1.39-1.61;OR=1.72,95%CI:1.57-1.88)in comparison to children with other MBDDs.Among children aged 12-17 years,the difference in proportion of meeting physical activity and screen time guidelines for children with vs.children without MBDD was larger than that among children aged 6-11 years.Furthermore,the above difference of meeting physical activity guidelines in ethnic minority children was smaller than that in white children.Conclusion: Children with MBDDs were less likely to meet individual or combined 24-hour movement guidelines than children without MBDDs.In educational and clinical settings,the primary focus should be on increasing physical activity and limiting screen time in children aged 12-17 years who have MBDDs;and specifically for white children who have MBDDs,increasing physical activity may help.

Keywords: Mental disorders;Physical activity;Sedentary behavior;Sleep

1.Introduction

Mental,behavioral,and developmental disorders (MBDDs),which have adverse physiological and psychological effects on the health and well-being of individuals across their lifespan,are among the top 10 leading causes of burden worldwide in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.1Adopting a healthy lifestyle during childhood could be an inexpensive and powerful approach to improving physical and mental health outcomes in adulthood and reducing relevant disease burdens caused by MBDDs.2,3Governments and relevant institutes from around the globe have successively released a series of 24-hour movement guidelines to promote an active lifestyle in children(e.g.,Canada,4Australia,5USA,6China,7World Health Organization,8etc.).However,these guidelines are based on a healthy population,and limited information exists regarding whether children with MBDDs could be expected to meet them.

Compared to their typically developing peers,children with MBDDs are more likely to experience unfavorable health outcomes,such as obesity-related conditions9and cardiovascular diseases,10which are ultimately related to energy imbalances and unhealthy lifestyles.11There is increasing interest in improving modifiable lifestyle factors to promote favorable prognosis and better quality of life.12,13Accumulating epidemiological evidence indicates that children with MBDDs aged 6-17 years were less likely to meet individual or combined 24-hour movement guidelines compared to children without MBDDs (Supplementary Table 1).However,these studies were limited,failing to examine the association in national large-scale surveys or across a variety of MBDDs.For example,most had small sample sizes and tended to focus on a specific group within the spectrum of MBDDs (e.g.,autism spectrum disorder (ASD),14attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder(ADHD),15anxiety,16or depression16,17)or combined various conditions and treated them in a single group (e.g.,neurodevelopmental disorders,18developmental disabilities19).Accordingly,it appears that the associations between the spectrum of MBDDs and adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines have not been studied in adequate details.

Table 1 Adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines in children with and without MBDDs.a

In addition,there were marked variations in burden by gender for MBDDs.For example,the burden of emotional disorder was greater in females than males and the burden of developmental disorder was greater in males than females.1Meanwhile,distinct patterns of occurrence related to age20and ethnicity21,22were found across various MBDDs in children and adolescents.20However,previous studies examining the associations between MBDDs and adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines by demographic characteristics have only focused on specific types of MBDDs,such as ASD,14intellectual disability,23depression,and so on.17To date,associations related to gender,age,and ethnicity are insufficiently characterized among children with various MBDDs.The National Survey of Children’s Health(NSCH)is a national,populationbased,cross-sectional study in the United States that provides substantial and valuable data for a comprehensive and systematic evaluation of not only a broad set of MBDDs but also adherence to individual and combined 24-hour movement guidelines.The detailed demographic information from NSCH allows us to perform a more granular assessment of the contributions of heterogenous demographic characteristics and to identify susceptible populations across various MBDDs.

The current study combines data from the NSCH from 2016 to 2020 in order to address the critical knowledge gap related to the relationship between MBDDs and adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines.It also examines whether the difference in proportion of adherence to these guidelines between children with and without MBDDs is affected by demographic characteristics,including gender,age,and race/ethnicity.

2.Methods

2.1. Study population

The present study used cross-sectional data from the NSCH from 2016 to 2020.The NSCH is a national survey on the health and wellbeing of children between the ages of 0 and 17 years in the USA.24Data were collected by the U.S.Department of Health and Human Services,Health Resources and Services Administration,Maternal and Child Health Bureau.We have requested the data from Child &Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative,Data Resource Center with permission (reference number: 11275).All of the survey procedures were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board.Written consent was provided by electronically submitting or paper mailing and was sent back to the U.S.Census Bureau.

2.2. Data collection

The detailed procedure for data collection can be found here: www.childhealthdata.org.24The NSCH included 2 stages of data collection: (a) households received a screener mailing to identify whether any children aged 0-17 years were living in the household;and (b) if a child lived in the household,one of the caregivers who was familiar with the health and healthcare needs of their child (usually the parent)was randomly selected to complete a more detailed,agespecific topical questionnaire.To minimize the respondent burden of caregivers,only 1 child per household was randomly selected to be a participant in the survey.

A total of 174,551 participants completed the topical NSCH survey between 2016 and 2020,including 50,212 in 2016,21,599 in 2017,30,530 in 2018,29,433 in 2019,and 42,777 in 2020.Survey results were weighted to represent all non-institutionalized children in the USA,and in each state as well as the District of Columbia,who live in housing units.Included in the final analysis were 119,406 participants aged 6-17 years with available information regarding MBDDs and adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines(Supplementary Fig.1).

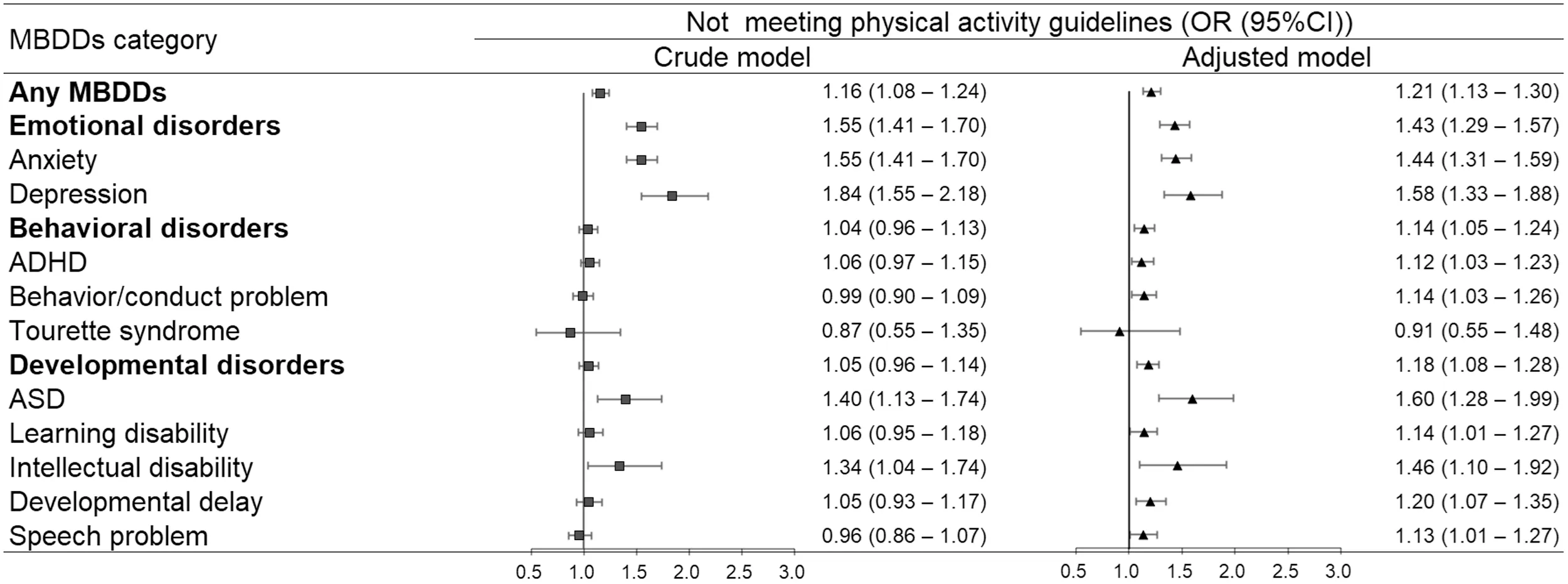

Fig.1.Associations between MBDDs and not meeting physical activity guidelines.Adjusted models were adjusted for child’s gender,age,race/ethnicity,highest parental education,and household income level.95%CI=95% confidence interval;ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder;ASD=autism spectrum disorder;MBDDs=mental,behavioral,and developmental disorders;OR=odds ratio.

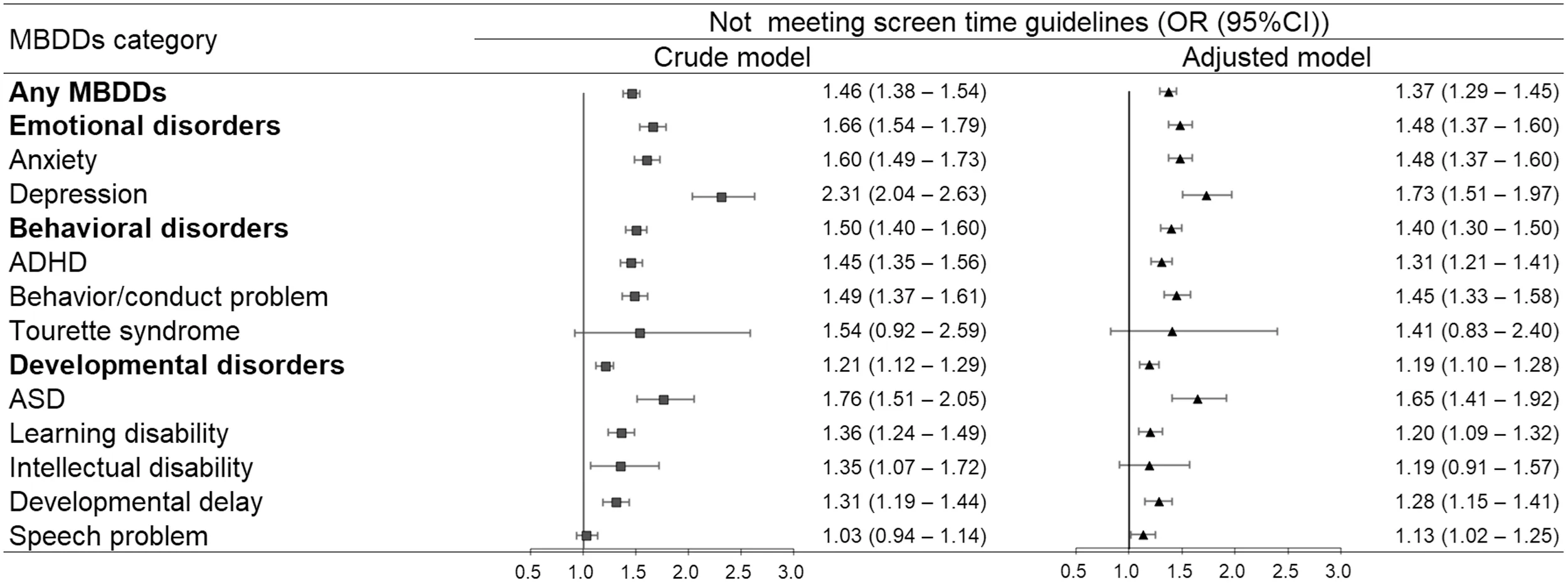

Fig.2.Associations between MBDDs and not meeting screen time guidelines.Adjusted models were adjusted for child’s gender,age,race/ethnicity,highest parental education,and household income level.95%CI=95% confidence interval;ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder;ASD=autism spectrum disorder;MBDDs=mental,behavioral,and developmental disorders;OR=odds ratio.

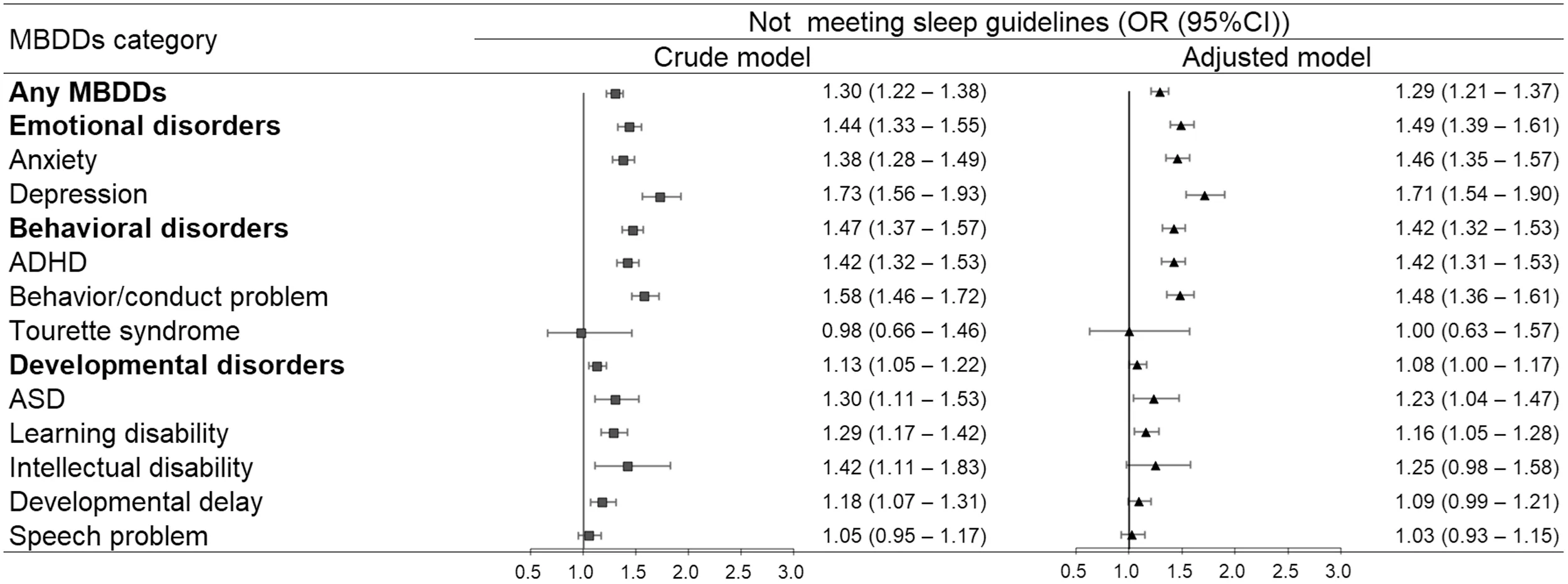

Fig.3.Associations between MBDD and not meeting sleep guidelines.Adjusted models were adjusted for child’s gender,age,race/ethnicity,highest parental education,and household income level.95%CI=95% confidence interval;ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder;ASD=autism spectrum disorder;MBDDs=mental,behavioral,and developmental disorders;OR=odds ratio.

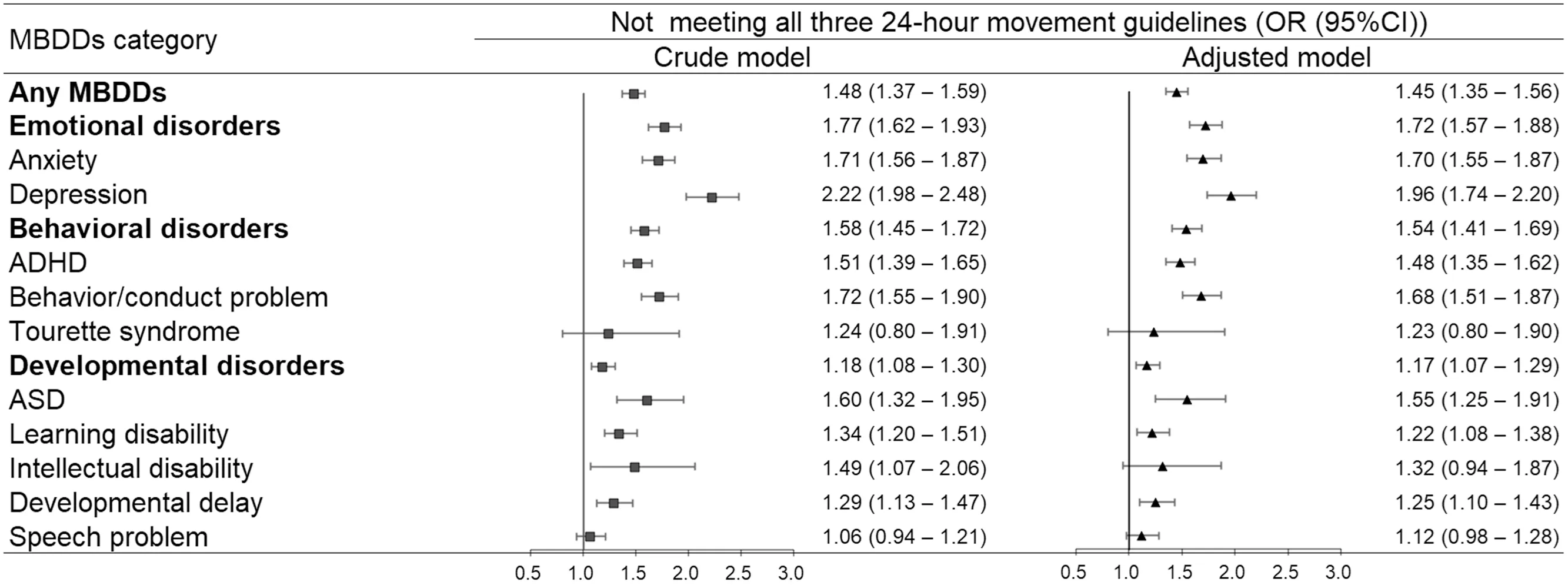

Fig.4.Associations between MBDDs and not meeting all three 24-hour movement guidelines.Adjusted models were adjusted for child’s gender,age,race/ethnicity,highest parental education,and household income level.95%CI=95% confidence interval;ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder;ASD=autism spectrum disorder;MBDDs=mental,behavioral,and developmental disorders;OR=odds ratio.TagedEnd

In the NSCH,MBDDs were identified based on parents’affirmative responses to the question: “Has a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that this child has (specified disorder)?” MBDDs were categorized as “emotional disorders”(anxiety problems or depression),“behavioral disorders”(ADHD,behavioral or conduct problems,or Tourette syndrome),and “developmental disorders” (ASD,learning disability,intellectual disability,developmental delay,or speech or other language disorder).A child was considered to have any MBDDs if the parent reported one or more of the above disorders.Similarly,a child was considered to have emotional,behavioral,or developmental disorders if the parent reported one or more of emotional,behavioral,or developmental disorders,respectively.These categories are not exclusive of each other.

Physical activity was assessed by the question:“During the past week,how many days did this child exercise,play a sport,or participate in physical activity for at least 60 min?”Response options included: “0 days”,“1-3 days”,“4-6 days”,and “every day”.A dichotomous variable was created to represent whether children met physical activity guidelines for at least 60 min/day of physical activity (every day,code as 0)or not(6 days or less,code as 1).4

Screen time was determined based on different questions from the 2016-2020 NSCH surveys.The 2016 and 2017 NSCH surveys asked the participants 2 relevant questions:“On an average weekday,about how much time does this child usually spend in front of a TV watching TV programs,videos,or playing video games?” and “On an average weekday,about how much time does this child usually spend with computers,cell phones,handheld video games,and other electronic devices doing things other than schoolwork?”Response options were:“None”,“Less than 1 hour”,“1 hour”,“2 hours”,“3 hours”,and “4 or more hours”.For both items,“Less than 1 hour”was set as 0.5 and“4 or more hours”as 4.The sum of the 2 items represented the total screen time of children from these 2 survey cycles.Surveys from 2018 to 2020 asked participants to respond to a combined item on screen time: “On most weekdays,about how much time did this child spend in front of a TV,computer,cellphone or other electronic device watching programs,playing games,accessing the internet or using social media?”.Response options included: “Less than 1 hour”,“1 hour”,“2 hours”,“3 hours”,and“4 or more hours”.A dichotomous variable was created based on total screen time to represent whether children met screen time guidelines of less than or equal to 2 h of screen time per day(code as 0)or not(>2 h,code as 1).4

Sleep duration was assessed by the question:“During the past week,how many hours of sleep did this child get on an average weeknight?” Response options included: “Less than 6 hours”,“6 hours”,“7 hours”,“8 hours”,“9 hours”,“10 hours”,and“11 or more hours”.Responses were divided into a dichotomous variable.Children aged 6-12 years who reported 9 or more hours of sleep per 24 h and adolescents aged 13-18 years who reported 8-10 h of sleep per 24 h were defined as meeting sleep guidelines(code as 0);all others were not(code as 1).4,25

A dichotomous variable was created for combined movement guidelines adherence (meeting at least one 24-hour movement guideline or not meeting all three 24-hour movement guidelines).Children were categorized as meeting at least one 24-hour movement guideline if they had one of the following movement behaviors:at least 60 min/day of physical activity every day;9 or more hours of sleep per 24 h for children aged 6-12 years,8-10 h of sleep per 24 h for adolescents aged 13-18 years;and 2 h or less of screen time (code as 0).Children were categorized as not meeting all three 24-hour movement guidelines if they met none of the guidelines outlined above(code as 1).

Demographic information on children’s gender,age,race/ethnicity,highest parental education,and household income level were included as covariates.Gender was recorded as either boy or girl.Age was grouped into 6-11 years and 12-17 years.Race/ethnicity was a dichotomized variable with white and ethnic minority (Black or African American and other).Highest parental education was categorized into less than high school,high school,some college or associate degree,and college degree or higher.Household income level (percentage of the federal poverty level) was classified based on the 2010 federal poverty line and included <100%,100%-199%,200%-399%,and≥400%.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Differences in demographic information and adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines across the 2 groups (children with and without MBDDs) were examined using χ2tests.Logistic regression models were used to assess the associations of MBDDs with individual or combined 24-hour movement guidelines adherence.We fitted crude models without adjustment,and we fitted models adjusting for children’s gender,age,race/ethnicity,highest parental education,and household income level.The subgroup analyses were conducted by gender(boysvs.girls),age(6-11 yearsvs.12-17 years),and race/ethnicity (whitevs.ethnic minority) to estimate specific differences in the associations between MBDDs and individual or combined 24-hour movement guidelines adherence related to gender,age,and ethnicity.The data from each subgroup were subjected to independent adjusted logistic regressions to obtain gender-,age-,and ethnicity-specific estimates of the odds ratio (OR).Based on the point estimate and standard error (SE),we used a two-sample test to analyze statistically significant differences in the estimated OR across categories.The same method was utilized in a previous study.26

We used survey weights,strata,and primary sampling units,which were provided along with the NSCH data,in all the analysis procedures to represent the noninstitutionalized children in the USA.All statistical analyses were performed in theRprogramming language (Version 4.1.0;R Foundation for Statistical Computing,Vienna,Austria).Allpvalues were two-sided,and apvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.Results

Of the 119,406 eligible children aged 6-17 years in the NSCH(2016-2020),38,571(29.5%(95%confidence interval(95%CI):29.0%-30.0%)) had MBDDs (Supplementary Table 1).Compared to children without MBDDs,children with MBDDs were more likely to be boys (59.4%,95%CI: 58.2%-60.0%),12-17 years old (55.1%,95%CI: 54.0%-56.0%),and white(69.3%,95%CI: 68.1%-70.0%).Families of children with MBDDs had low socioeconomic status as determined by their parent/caregiver’s education level,household income,and poverty level.The weighted proportion of those meeting the guidelines for physical activity (20.3%vs.22.8%),screen time (37.0%vs.46.2%),sleep (60.7%vs.66.7%),and at least one 24-hour movement guideline (77.3%vs.83.4%) among children with MBDDs was significantly lower than among children without MBDDs (allp<0.001,Table 1).Of these,the weighted proportion was lowest when it came to meeting physical activity guidelines.As shown in Figs.1-4,the adjusted models found that children with MBDDs were more unlikely to meet physical activity,screen time,sleep,or at least one 24-hour movement guideline (OR=1.21,95%CI: 1.13-1.30;OR=1.37,95%CI: 1.29-1.45;OR=1.29,95%CI: 1.21-1.37;OR=1.45,95%CI: 1.35-1.56) compared to children without MBDDs.In addition,children with emotional disorders had the highest odds of not meeting physical activity,screen time,sleep,or all three 24-hour movement guidelines (OR=1.43,95%CI: 1.29-1.57;OR=1.48,95%CI: 1.37-1.60;OR=1.49,95%CI: 1.39-1.61;OR=1.72,95%CI: 1.57-1.88) relative to children with behavioral disorders and developmental disorders.

The weighted proportions of children with different MBDDs meeting individual or combined 24-hour movement guidelines by gender,age,and race/ethnicity are shown in the Supplementary Figs.2-13.We observed no genderspecific difference in all associations (allp>0.05,Supplementary Figs.14-17).Among children aged 12-17 years,the difference in proportion for those withvs.those without MBDD who met physical activity (14.8%vs.17.7%;27.1%vs.27.6%,Supplementary Fig.6) and screen time guidelines(26.3%vs.34.6%;50.2%vs.57.0%,Supplementary Fig.7)was larger than that among children aged 6-11 years(z=2.69,p=0.007;z=3.18,p=0.001,respectively;Supplementary Figs.18-19).Furthermore,the proportional difference in meeting physical activity guidelines (21.4%vs.20.7%;19.9%vs.23.9%,Supplementary Fig.10) for ethnic minority children was smaller than that for white children(z=-2.36,p=0.018,Supplementary Fig.22).

4.Discussion

Children with and without MBDDs tended not to meet all three 24-hour movement behavioral standards,especially the physical activity standards.Children with MBDDs were less likely to meet all three 24-hour movement guidelines than children without MBDDs.Taking different categories of MBDDs into consideration,children with emotional disorders were the least likely to meet these guidelines.We also found specific differences related to age and ethnicity in the proportion of children with and without MBDDs who adhered to the 24-hour movement guidelines.

We found that children with MBDDs were the most unlikely to meet all three 24-hour movement guidelines,as compared to individual movement guidelines,indicating the need for comprehensive lifestyle modifications for these children.It should also be noted that children with MBDDs who do not achieve guidelines might face increased risk for exacerbated symptoms as they grow into adolescence.27Several meta-analyses have highlighted that meeting all three 24-hour movement guidelines across the lifespan is favorably associated with psychosocial health indicators (e.g.,social-cognitive development,behavioral and emotional problems,mental health) as compared with meeting fewer or none of these guidelines.28,29Recent evidence supports positive associations between adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines and mental health in a dose-response gradient.27In addition,specific combinations of physical activity,screen time,and sleep guidelines adherence have been reported to be associated with various health indicators among children and adolescents.30,31Therefore,a consideration of the combined effects of these 24-hour movement behaviors and the health implications of time spent in each behavior could inform the development of effective interventions and treatments for children with MBDDs.Additional studies exploring whether children with MBDDs could gain different benefits from specific combinations of adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines are still needed.

Among the three 24-hour movement guidelines,physical activity was identified as the most challenging one.Previous research using the 2016 NSCH data suggested that children aged 10-17 years with chronic conditions were least likely to meet the physical activity guidelines compared to the other 24-hour movement guidelines.32We extended these findings by focusing on all MBDDs,and our results reveal that this trend has remained consistent over the last 5 years.Reversing the trend of declining physical activity in children with MBDDs could help with disease prevention.Indeed,evidence shows that a 10% reduction in the number of individuals not meeting physical activity guidelines could prevent 533,000 premature deaths every year in the general community.33

Among children with different categories of MBDDs,those with emotional disorders (i.e.,anxiety or depression)performed the worst in terms of meeting the 24-hour movement guidelines compared to children with behavioral or developmental disorders.Notably,children with depression had higher odds of not meeting these guidelines than children with anxiety.Globally,depression and anxiety continue to be among the leading causes of disease burden worldwide,with relatively higher prevalence estimates and disability weights than many other mental disorders.1Emotional disorders not only harm physical and psychosocial health and increase social burden in their own right,they also elevate the risk of other negative health outcomes,such as role impairment,psychiatric comorbidity,and suicidal behavior.34,35Establishing healthy lifestyles and meeting the 24-hour movement guidelines would contribute to reducing healthcare burdens for children with MBDDs by alleviating their clinical symptoms.12Some interventions have already been developed and proven effective in different settings,including at home,at school,and in communities.36,37Children with emotional disorders were physically capable of attending school in most cases;38therefore,the school-based approach might be an effective one for promoting their adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines.39,40However,home-based intervention may be more suitable for children with other MBDDs since these children tend to spend more time at home.Future studies conducted by public health practitioners,educators,and clinicians are warranted to develop targeted interventions according to the types of MBDDs we see in children.

Our results also highlighted significant differences with respect to age and ethnicity,which further indicates the importance of interventions targeted at increasing physical activity and limiting screen time in children aged 12-17 years who have MBDDs and at increasing physical activity in white children with MBDDs.Our findings agree with those of previous studies showing that children with disabilities tend to become more inactive with increasing age.41Regarding ethnic-specific differences in physical activity among children,previous studies showed controversial findings.42-45Studies based on objective physical activity data consistently show that white children are less active than ethnic minorities.42However,studies based on self-reported physical activity report that ethnic minorities generally engage in lower levels of physical activity than white children.43-45This is inconsistent with the results of the present study.The discrepancy could be explained by an underestimation of physical activity participation in self-reported data from ethnic minorities.46Another possible explanation is that a national focus on eliminating health disparities among different ethnicities has had a positive response.47Our findings indicate that if a population-level change has already occurred with respect to physical activity among ethnic minorities,the long-standing goal of comprehensive lifestyle modifications for white children should not be overlooked.

In addition to the implications of subgroup analyses,another important advantage of this descriptive study is that the data may be useful for estimating the disease burden of a population and,consequently,for planning resource needs.Information on the odds of children with various MBDDs not meeting the 24-hour movement guidelines may help researchers in related fields tailor interventions to best meet the needs of different population subgroups.For example,the associations of ADHD from behavioral disorders and ASD from developmental disorders with combined movement guidelines adherence were not as strong as expected in this study.With respect to the three 24-hour movement guidelines,children with ADHD were more likely to meet physical activity guidelines while children with ASD were more likely to meet sleep guidelines.It is possible that these data are overreported by parents due to the presence of physical hyperactivity in ADHD48and the concern toward sleep quality in children with ASD.49Nonetheless,according to our data,interventions targeting sleep insufficiency and/or excessive screen time in ADHD or interventions targeting physical inactivity and/or excessive screen time in ASD may be more necessary for these children as we aim to improve their adherence to the combined movement guidelines.This is merely 1 example of how this nationally descriptive data can be interpretated and utilized.

This study had several limitations that should be addressed.First,this cross-sectional study cannot elucidate the causal link between MBDDs and adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines in children.Second,we used parent-reported questionnaires to measure all variables,which might subject the data to recall bias.Third,due to the large-scale nature of NSCH data collection,the measurements of physical activity,screen time,and sleep were subjective and simplistic.Objective activity measurements were not used and detailed information,such as activity intensity,the content of screen viewing,and sleep quality,was not reported.Fourth,data from the 2019 and 2020 NSCH were collected during coronavirus disease 2019 related restrictions,which may have affected the results.Finally,typically developing children who met 24-hour movement guidelines might have improved physical,mental,cognitive,and social functioning,27,50,51but the health benefits of meeting the 24-hour movement guidelines might differ in children with MBDDs due to physiological responses,comorbidities,treatments,and medication experiences.However,estimating the associations of meeting individual and combined 24-hour movement guidelines with these health indicators in children with and without MBDDs was beyond the scope of the current study,and further studies are still needed.Despite these limitations,our study had notable strengths,including a large-scale sample size based on the 2016-2020 NSCH data,comprehensive information on individual and combined 24-hour movement guidelines adherence,and various categories of MBDDs,all of which could help us to improve the reliability of our findings.

5.Conclusion

Our study indicated that in the USA,children performed badly with respect to all three 24-hour movement behaviors.Children with MBDDs were more unlikely to meet individual or combined guidelines than children without MBDDs.We also found that populations at higher risk include children with emotional disorders,children aged 12-17 years,and white children.Health promotion interventions have been shown to be effective and should continue to be promoted to parents of children with MBDDs to improve awareness of healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2019B030335001),the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82103794),Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation(2021A1515011757),General Administration of Sport of China and China Institute of Sport Science (19-21),and Guangxi Key Research and Development Plan(GUIKEAB18050024).The authors greatly appreciate the work of the U.S.Department of Health and Human Services,Health Resources and Services Administration,Maternal and Child Health Bureau,and the Data Resource Center on Child and Adolescent Health for collecting and providing data.In addition,the authors also thank the parents,who have been generous with their time,for answering the 2016-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health.

Authors’contributions

NP and LZL participated in drafting,writing,and revising the manuscript;XHL and GHD had full access to all of the data and took responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis;GPN assisted in the interpretation of the data analysis and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript;XW and XXO helped to perform statistical analysis;LC,JJ,and QF helped to draft the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2022.12.003.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2023年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2023年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Impact loading in female runners with single and multiple bone stress injuries during fresh and exerted conditions

- Are EPB41 and alpha-synuclein diagnostic biomarkers of sport-related concussion?Findings from the NCAA and Department of Defense CARE Consortium

- Factors and expectations influencing concussion disclosure within NCAA Division I athletes:A mixed methodological approach

- Effects of contact/collision sport history on gait in early-to mid-adulthood

- Refinement of saliva microRNA biomarkers for sports-related concussion

- Lacrosse-related injuries in boys and girls treated in U.S.emergency departments,2000-2016