Replacement of leisure-time sedentary behavior with various physical activities and the risk of dementia incidence and mortality:A prospective cohort study

Ying Sun,Chi Chen,Yuetin Yu,Hojie Zhng,Xio Tn,Jihui Zhng,Lu Qi,Yingli Lu,*,Ningjin Wng,*

a Institute and Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism,Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital,Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine,Shanghai 200011,China

b Department of Medical Sciences,Uppsala University,Uppsala 751 85,Sweden

c School of Public Health,Zhejiang University,Hangzhou 310058,China

d Center for Sleep and Circadian Medicine,The Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University,Guangzhou 510180,China

e Department of Epidemiology,School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine,Tulane University,New Orleans,LA 70112,USA

f Department of Nutrition,Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health,Boston,MA 02115,USA

g Channing Division of Network Medicine,Department of Medicine,Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School,Boston,MA 02115,USA

Abstract Background: Whether or not there is targeted pharmacotherapy for dementia,an active and healthy lifestyle that includes physical activity(PA)may be a better option than medication for preventing dementia.We examined the association between leisure-time sedentary behavior(SB)and the risk of dementia incidence and mortality.We further quantified the effect on dementia risk of replacing sedentary time with an equal amount of time spent on different physical activities.Methods: In the UK Biobank,484,169 participants (mean age=56.5 years;45.2% men) free of dementia were followed from baseline(2006-2010) through July 30,2021.A standard questionnaire measured individual leisure-time SB (watching TV,computer use,and driving)and PA(walking for pleasure,light and heavy do-it-yourself activity,strenuous sports,and other exercise)frequency and duration in the 4 weeks prior to evaluation.Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype data were available for a subset of 397,519 (82.1%) individuals.A Cox proportional hazard model and an isotemporal substitution model were used in this study.Results: During a median 12.4 years of follow-up,6904 all-cause dementia cases and 2115 deaths from dementia were recorded.In comparison to participants with leisure-time SB <5 h/day,the hazard ratio ((HR),95% confidence interval (95%CI)) of dementia incidence was 1.07(1.02-1.13)for 5-8 h/day and 1.25(1.13-1.38)for >8 h/day,and the HR of dementia mortality was 1.35(1.12-1.61)for >8 h/day.A 1 standard deviation increment of sedentary time(2.33 h/day)was strongly associated with a higher incidence of dementia and mortality(HR=1.06,95%CI: 1.03-1.08 and HR=1.07,95%CI: 1.03-1.12,respectively).The association between sedentary time and the risk of developing dementia was more profound in subjects <60 years than in those ≥60 years(HR=1.26,95%CI:1.00-1.58 vs.HR=1.21,95%CI:1.08-1.35 in>8 h/day,p for interaction=0.013).Replacing 30 min/day of leisure sedentary time with an equal time spent in total PA was associated with a 6%decreased risk and 9%decreased mortality from dementia,with exercise(e.g.,swimming,cycling,aerobics,bowling)showing the strongest benefit (HR=0.82,95%CI: 0.78-0.86 and HR=0.79,95%CI: 0.72-0.86).Compared with APOE ε4 noncarriers,APOE ε4 carriers are more likely to see a decrease in Alzheimer’s disease incidence and mortality when PA is substituted for SB.Conclusion: Leisure-time SB was positively associated with the risk of dementia incidence and mortality.Replacing sedentary time with equal time spent doing PA may be associated with a significant reduction in dementia incidence and mortality risk.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease;Apolipoprotein E;Dementia;Isotemporal substitution model;Physical activity;Sedentary behavior

1.Introduction

Dementia is a growing public health concern.Worldwide,1 new case of all-cause dementia is detected every 4 s,1and the total number will reach 115 million by 2050.2According to a report by Alzheimer’s Research UK,32% of people born in 2015 will develop dementia,which has already become the leading cause of death for women in the UK and the second for men.3

The most recent World Health Organization guidelines on physical activity (PA) and sedentary behavior (SB) mention that SB is “any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure of 1.5 metabolic equivalents or lower while sitting,reclining,or lying”.4Opportunities for leisure-time SBs like watching television are ubiquitous in modern society,and time spent on sedentary pursuits has significantly increased over recent decades.5Research on how SBs impact health has also increased,6and more attention has been paid to its effect on the elderly.7A meta-analysis found that SB was independently associated with dementia.8Nevertheless,most previous studies estimate the effect of a sedentary lifestyle while adjusting for PA as a covariate.9These models fail to consider that a 24-h day is finite,so risk reduction depends on which activities displace SB.Recently,isotemporal substitution modeling analyses have directly addressed such issues by displacing sedentary time with an equivalent time spent on PA.10-12Although current public health recommendations encourage people to “sit less and move more”,it remains unclear which types of PA are ideal alternatives to SB.Even less evidence exists regarding the magnitude to which substituting SBs with various categories of PA reduces the risk of dementia and its related mortality.

In addition,genetic predisposition has been acknowledged as an important contributor to the development of dementia.13Specifically,carrying the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele appears to be consistently associated with an increased risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).14Yet it remains unknown whether the effect of replacing leisure-time SB with PA would be different in persons with different APOE genotypes.

In the present study,we explored the following questions in a large prospective cohort: Is there an association between leisure-time SB and the risk of dementia incidence and mortality? Could specific types of PA substituted for leisure sedentary time confer benefits with respect to dementia risk and mortality reduction? Would the replacement impact be different for participants with different APOE genotypes?

2.Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and sample

Our data source is UK Biobank,a population-based cohort study including approximately 500,000 community-dwelling adults across the UK aged 37-73 years and recruited between 2006 and 2010 (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).Detailed information on participants has been described previously.15We declare that all data are publicly available in the UK Biobank repository.15The North West Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee Study approved the UK Biobank study,and all participants provided written informed consent.

In UK Biobank cohort including 502,505 participants,we excluded participants who withdrew from the follow-up(n=44),those with physician-diagnosed dementia at baseline(n=495) and in the first 2 years (n=271),and those missing reliable information on SBs (n=17,526).Thus,484,169 participants were included in the main analysis;among them,397,519 (82.1%) individuals of European descent had APOE genotype data.

2.2. Exposure:SBs and PA

Information on leisure-time SB and PA was collected by a standard questionnaire based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire form,which was validated and used in prior studies.16,17As suggested previously,17and based on the information provided in the UK Biobank,leisure-time SBs included driving,computer use (not at work),and watching TV.If the time participants spent driving,using a computer,and watching TV varied greatly from day to day,they were asked to give the average time for a 24-h day over the previous 4 weeks.To increase the reliability of exposure factors,individuals who reported extreme sedentary hours (TV plus computer use ≥12 h/day and driving time ≥8 h/day) were excluded.For other participants,excluded time spent sleeping or performing life activities like working and eating,the“disposable time”was <24 h.The total SB duration was categorized into <5 h/day,5-8 h/day,and >8 h/day.The same questionnaire was repeated in 3 follow-up surveys (2012-2013,2014+,and 2019+) intended to record SB time.The correlation between baseline SB time and that in the follow-up surveys was relatively high (Spearmanr=0.642,0.565,and 0.519,respectively,allp<0.001)(Supplementary Table 1).

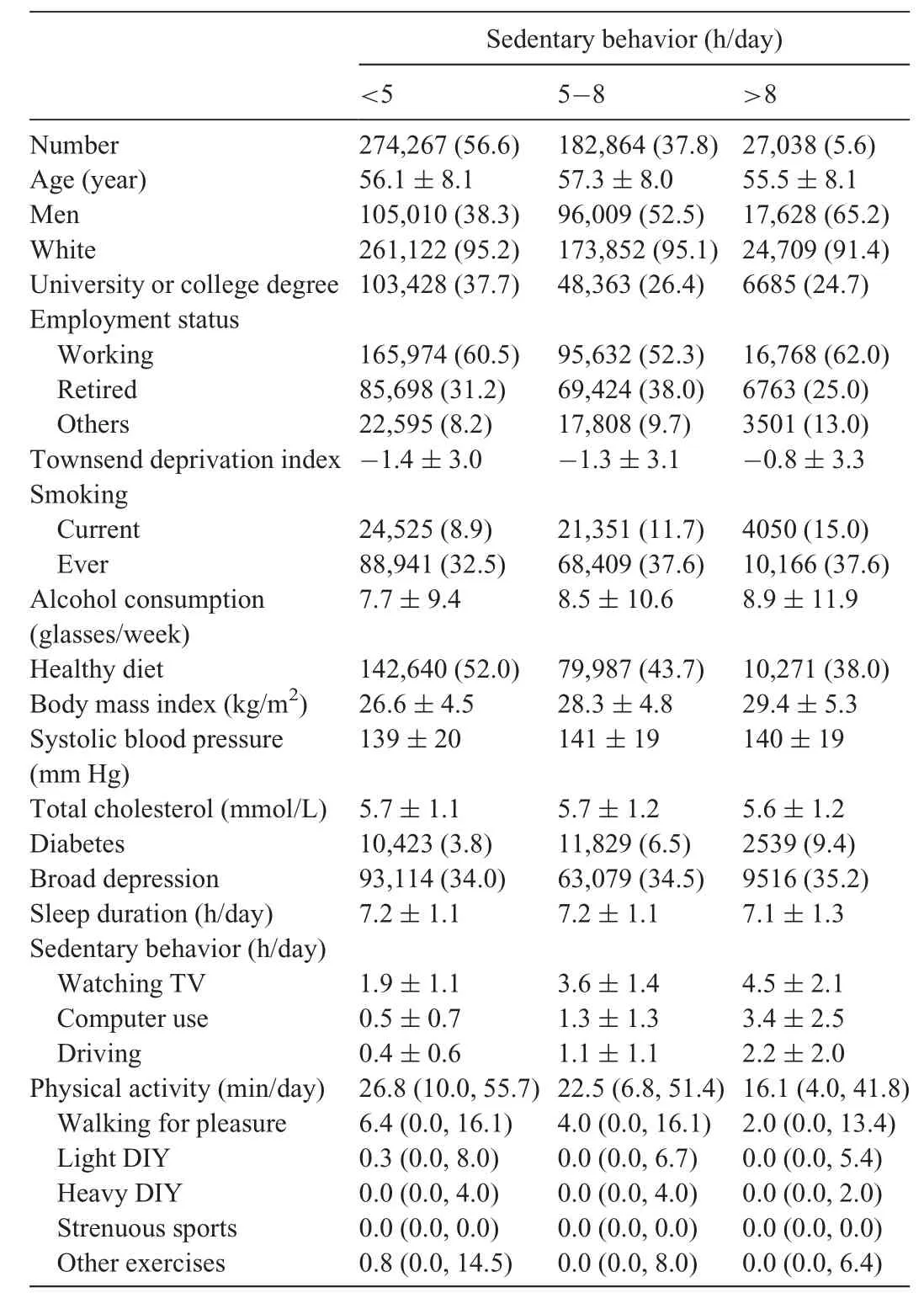

Table 1 UK Biobank participant characteristics by sedentary behavior time(n=484,169).

Different PAs performed at home and during leisure time were divided into types in the questionnaire: (a) walking for pleasure;(b) light do-it-yourself (DIY) activity (e.g.,pruning,watering the lawn);(c) heavy DIY activity (e.g.,weeding,lawn mowing,carpentry,digging);(d) strenuous (defined as inducing sweat and hard breathing) sports;and (e)other exercise (e.g.,swimming,cycling,aerobics,bowling).PAs were sorted into types based on their relatively similar metabolic equivalents,which were provided in previous literature.18We collected the average frequency and duration of each type of PA performed during the previous 4 weeks and calculated the total PA time by summing them.In addition,total discretionary time in our study included the average time spent engaging in SBs and PA in a single day.The detailed questionnaire information is listed in the supplemental file.A multicollinearity test was also performed,and it showed no collinearity among these activity types(Supplementary Table 2).

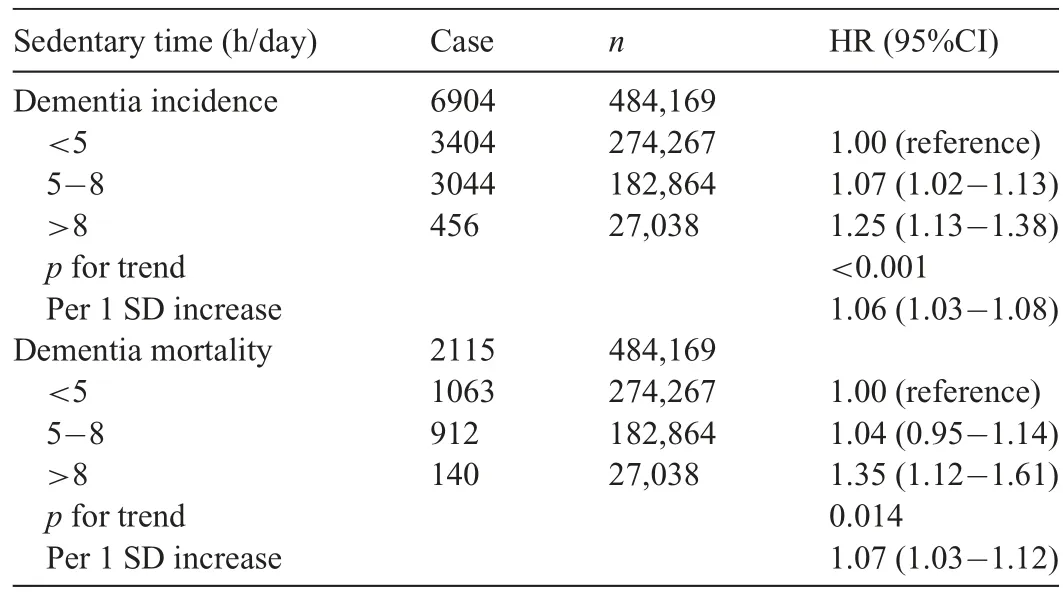

Table 2 Association between sedentary behavior time and dementia incidence and mortality.

2.3. Outcome:Dementia

The primary outcomes included incident dementia and dementia-related death.Additionally,their 2 major component endpoints,AD and vascular dementia (VD),were secondary outcomes.Incident dementia information was obtained from primary care and hospital inpatient records extracted from the“first occurrence of health outcomes defined by a 3-character International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision code” (category ID in UK Biobank 1712).Information on dementia-related death (i.e.,dementia was either the primary cause or a contributing cause of death) was obtained through death certificates held within the National Health Service Central Register to July 30,2021.The detailed International Classification of Diseases codes are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

2.4. APOE genotype information

UK Biobank performed the genotyping,imputation,and quality control,and the detailed genetic information was reported previously.19We used variable genetic kinship to other participants (Biobank field ID 22021) as a covariate when performing genetic analysis to limit confounding from population relatedness.20The APOE haplotypes (ε2/ε3/ε4)were determined by rs429358 and rs7412.The APOE ε4 genotype has a recognized association with susceptibility to AD.21Participants of European descent were categorized into APOE ε4 carriers(1 or 2 ε4 alleles)and APOE ε4 noncarriers(no ε4 allele).22

2.5. Covariates

The following potential confounders were included in the analysis: age,sex,ethnicity (white/others),education (university or college degree/others),employment status (working/retired/others),Townsend index reflecting socioeconomic status (continuous),23smoking status (current/ever/never),alcohol consumption (glasses per week),healthy diet score(score ≥4,detailed information is given in the supplemental file),body mass index ((BMI) continuous),total cholesterol(continuous),systolic blood pressure(continuous),diabetes(yes/no),broad depression (yes/no),sleep duration (h/day,continuous),genetic kinship to other participants,and cognitive function (mean time to correctly identify matches,continuous).If covariate information was missing,we used multiple imputation for continuous variables and a missing-indicator approach for categorical variables.The missing percentages ranged from 0.3%(smoking status)to 6.8%(total cholesterol).

2.6. Statistical analyses

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics,Version 25(IBM Corp.,Armonk,NY,USA).Apvalue <0.05 indicated statistical significance (two-sided).Baseline characteristics of the study population are reported as means,medians,or percentages by categories of sedentary hours.The follow-up time was determined from the baseline date(date of attending the assessment center) to the diagnosis of dementia,death,or censoring date(July 30,2021),whichever came first.

First,to measure the association between leisure-time SB and dementia incidence and mortality,the Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratio(HR)and 95% confidence interval (95%CI).The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals.The model was adjusted for age,sex,ethnicity,education,employment status,Townsend index,smoking status,alcohol consumption,healthy diet score,BMI,total cholesterol,systolic blood pressure,diabetes,broad depression,and sleep duration.Then,the interaction analysis between (a) SB time and (b) APOE category for the risk of all-cause dementia and AD was performed by using the likelihood ratio test to compare models with and without a cross-product term.In the preplanned secondary analyses,we also tested whether sex,age,BMI,and economic status modified the association between SB time and dementia events.

Second,an isotemporal substitution model was used to estimate the effect of substituting SBs with an equal time spent doing different types of physical activities (e.g.,we replaced SBs with walking for pleasure by taking SBs out of the model).10The isotemporal substitution model could be expressed as follows:h(t)=h0(t) exp (β1walking for pleasure+β2light DIY+β3heavy DIY+β4strenuous exercise+β5other exercises+β6total discretionary activity time+β7covariates),where β1-β7are coefficients of respective activities or covariates.The total discretionary time=SB time+total PA time (walking for pleasure,light DIY,heavy DIY,strenuous exercise,and other exercises).The model eliminates 1 activity component at a time (e.g.,SB) while keeping discretionary time unchanged.The coefficient β6represents the omitted activity component (in this case,SB),and the remaining coefficients represent the consequence of substituting 30 min of a specific activity for SB while holding the other activity types constant.The choice of a 30-min/day was arbitrary,but the unit of measurement(min/day)was based on the original assessment.

Third,the isotemporal substitution model was evaluated separately according to sex (men or women),age (<60 years or≥60 years),BMI (<25 kg/m2or ≥25 kg/m2),economic status(<-1.3526 or ≥-1.3526),and APOE genotype (ε4 carrier or ε4 noncarrier) to understand whether the isotemporal effects of the physical activities would vary among different subgroups.

Finally,we conducted several sensitivity analyses to confirm the robustness of our findings,excluding participants who had missing covariates and further adjusting for baseline cognitive function(mean time to correctly identify matches).

3.Results

The flow diagram and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 and Supplemental Fig.1.In this cohort,218,647(45.2%) were men,and the mean baseline age was 56.5 ±8.1 years(mean±SD).Overall,participants with more sedentary time were more likely to be men and to have a lower education level and economic status.Compared to the individuals with leisure sedentary time <5 h/day,those with leisure sedentary time >8 h/day tended to drink more,be a current smoker,and have a higher BMI.A higher prevalence of diabetes and broad depression symptoms were also found among participants with more sedentary time.

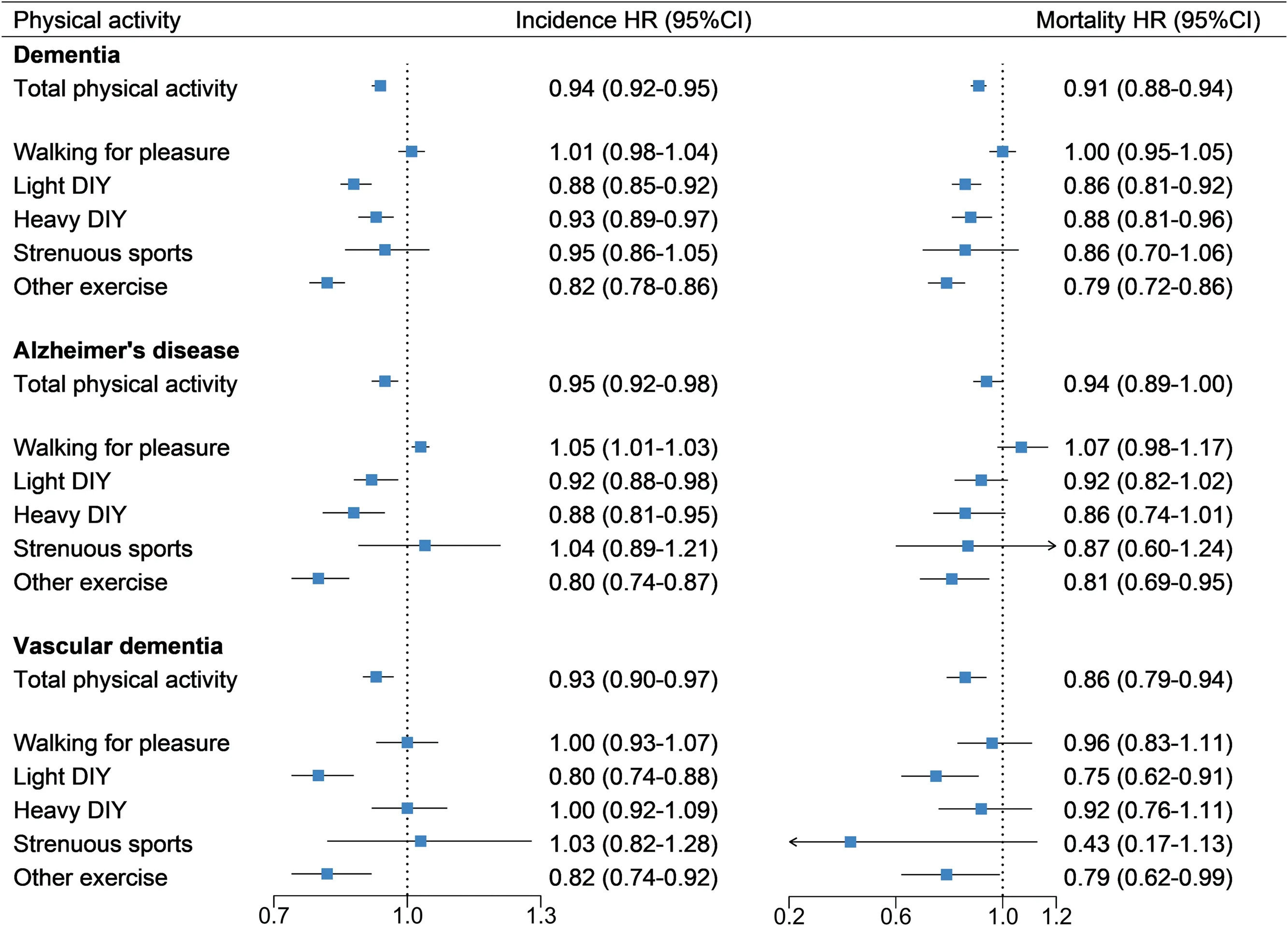

Fig.1.Multivariate HRs of isotemporal substitution model for incidence and mortality of all-cause dementia,Alzheimer’s disease,and vascular dementia.Data are HR (95%CI).The model was adjusted for age (continuous),sex,ethnicity (white/others),education (university or college degree/others),employment status(working/retired/others),Townsend index(continuous),smoking status(current/ever/never),alcohol consumption(glasses/week),healthy diet score ≥4(yes/no),body mass index (kg/m2),total cholesterol (mmol/L),systolic blood pressure (mmHg),sleep duration (h/day),diabetes (yes/no),and broad depression (yes/no).95%CI=95%confidence interval;DIY=do-it-yourself;HR=hazard ratio.

During 5,869,806 person-years (median 12.4 years) of follow-up,6904 all-cause dementia cases were recorded after 2 years,including 2642 AD,1376 VD,and 2115 deaths due to dementia(Table 2).Table 2 presents the associations between categories of SB time and dementia incidence and mortality.In the multivariable adjusted model,increased leisure sedentary time was significantly associated with a higher risk of both dementia incidence and mortality (per 1 SD,HR=1.06,95%CI:1.03-1.08 and HR=1.07,95%CI: 1.03-1.12,respectively) after adjusting for age,sex,ethnicity,education,employment status,Townsend index,smoking status,alcohol consumption,ideal healthy diet,total cholesterol,systolic blood pressure,BMI,diabetes,broad depression,and sleep duration.Compared to participants in the lowest category(<5 h/day),the risk of incident dementia was significantly higher for 5-8 h/day (HR=1.07,95%CI: 1.02-1.13) and >8 h/day(HR=1.25,95%CI:1.13-1.38)(pfor trend <0.001).There was a significant increase in SB over 8 h/day for dementia-related death(HR=1.35,95%CI:1.12-1.61)(pfor trend=0.014).Theresults were similar when the outcomes of AD and VD were considered separately(Supplementary Table 4).

The stratified analysis showed significant interactions between age and sedentary time for incident dementia (pfor interaction=0.013).The associations were more profound among subjects <60 years of age than among those ≥60(HR=1.16vs.1.06 in 5-8 h/day and HR=1.26vs.1.21 in >8 h/day)(Supplementary Table 5).Sex,BMI,economic status,and APOE genotype did not significantly modify the above associations.

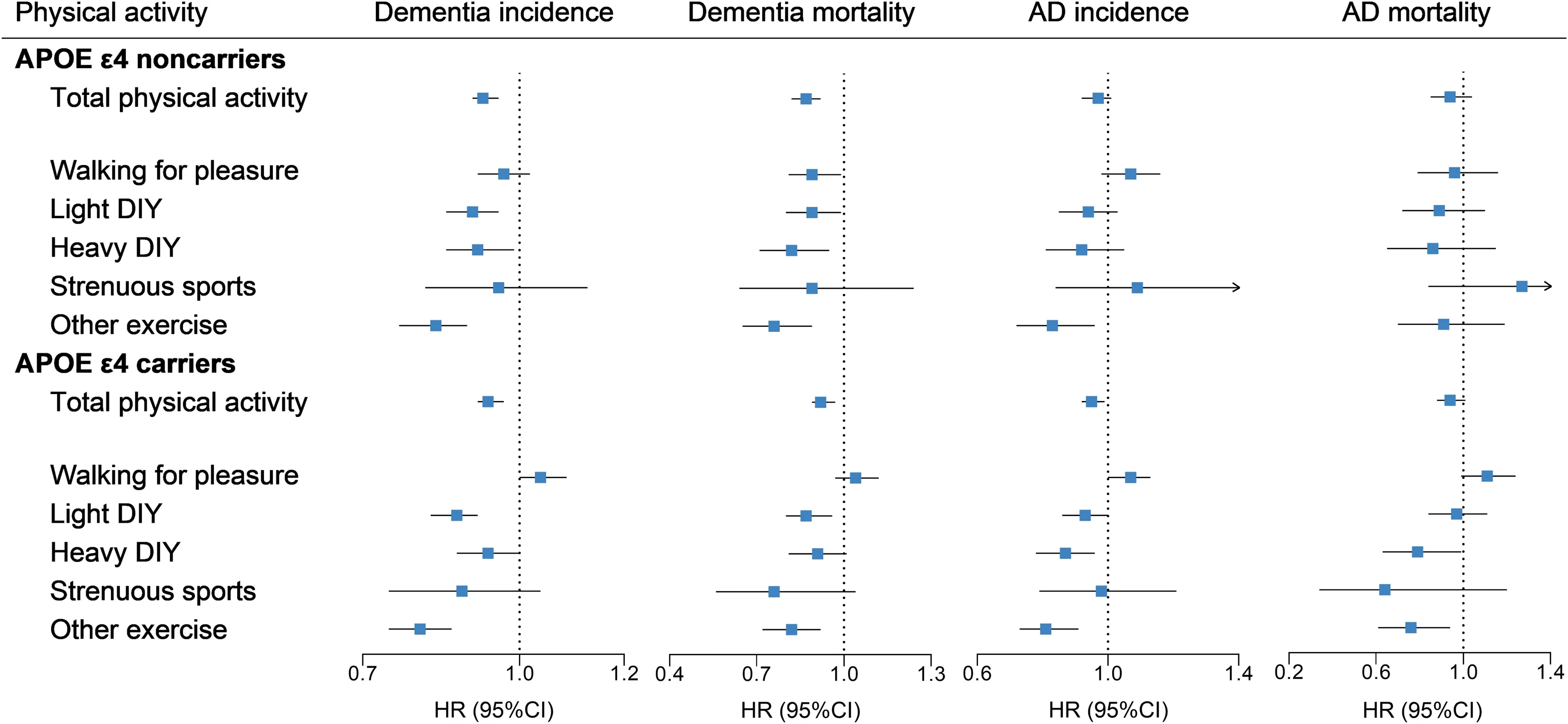

We found that replacing 30 min/day of leisure-time SBs with an equal amount of time of PA was significantly associated with a decreased risk of incident all-cause dementia,AD,and VD(by 6%,5%,and 7%,respectively)as well as mortality from dementia,AD,and VD (by 9%,6%,and 14%,respectively)(Fig.1).The intensity of the various physical activities may play a key role in their impact.Even substituting 30 min/day of SBs with an equal amount of time spent doing light DIY (such as pruning or watering the lawn) was associated with a 12% and 14% lower risk of dementia incidence and mortality,respectively.Further stratified analyses showed that the substitution effect of structured exercise was more profound in participants <60 years old than in those≥60 years old.Overall benefits were similar in men and women (Supplementary Table 6).The substitution effect appeared to be more profound among APOE ε4 carriers,with heavy DIY and other exercise showing significant benefits(HR=0.93,95%CI: 0.86-1.00 and HR=0.81,95%CI:0.73-0.91 for AD incidence;HR=0.79,95%CI:0.63-0.99 and HR=0.76,95%CI: 0.61-0.94 for AD mortality) (Fig.2 and Supplementary Table 7).

Fig.2.Replacing 30 min/day of sedentary behavior time with different types of physical activity according to APOE groups.Data are HR (95%CI).The model was adjusted for age(continuous),sex,ethnicity(white/others),education(university or college degree/others),employment status(working/retired/others),Townsend index(continuous),smoking status(current/ever/never),alcohol consumption(glasses/week),healthy diet score ≥4(yes/no),body mass index(kg/m2),total cholesterol (mmol/L),systolic blood pressure (mmHg),sleep duration (h/day),diabetes (yes/no),broad depression (yes/no),and genetic kinship to other participants.95%CI=95%confidence interval;AD=Alzheimer’s disease;APOE=apolipoprotein E;DIY=do-it-yourself;HR=hazard ratio.

In sensitivity analyses,after excluding participants with incomplete covariates,we obtained a positive association between SB time and dementia risk;the replacement impact was similar (Supplementary Tables 8 and 9).After further adjusting for cognitive function,the association of SB duration with dementia incidence and mortality was still prominent(Supplementary Table 10).

4.Discussion

This prospective cohort study,with nearly half a million participants and 12 years of follow-up,has offered the following findings: First,longer periods of leisure-time SB were associated with a higher risk of dementia incidence and mortality;this association was stronger among individuals≤60 years of age.Second,replacing 30 min/day of SB time with an equal amount of time spent doing different physical activities was associated with a 7%-18% decreased risk of dementia incidence and 12%-21% decreased mortality from dementia,with more intense exercises showing a stronger benefit.Third,compared with APOE ε4 noncarriers,APOE ε4 carriers are more likely to see reduced AD incidence and mortality when PA is substituted for SB.

Whether or not there is targeted pharmacotherapy for dementia treatment and prevention,a better option for some may be an active and healthy lifestyle,which effectively acts as a “polypill”,providing multiple and compounding benefits.24Since sitting may be required for work,we were more concerned about the impact of SBs during leisure time,which are more within the control of an individual to change.In a meta-analysis summarizing 18 cohort studies with 250,063 participants,the authors found a pooled 30%increased risk of dementia with SB.8However,most previous studies provided limited information about sedentary time,inconsistent definitions of SB (which could lead to bias in the effect size estimates),and insufficient information on dementia subtypes.8No study done to date has looked at whether SB is associated with increased dementia mortality.Our results indicated that sedentary time (>8 hvs.<5 h or 1 SD increment) was positively associated with risk for both dementia incidence and mortality.Younger individuals(>60 years) could be especially susceptible to the impact of sedentary time on increasing incident dementia—a finding that is rarely mentioned in the literature but could serve as a hint for early prevention.

Many studies have found that PA is associated with a lower risk of developing dementia;25-28yet,the results remain inconsistent.This could be due to the age scope of participants29,30or the type,duration,and frequency of PA.31While accelerometers provide an objective estimate of the duration and intensity of a PA,they offer limited information about the type and frequency of activities,32and the results for energy expenditure may vary across different devices,such as wrist-,arm-,waist-,and thigh-mounted accelerometers,depending on activity type.33,34In contrast,questionnaires might be suitable to collect information on type and frequency of physical activities,especially moderate-to-vigorous activities,but they may overestimate activity time.32However,a moderate correlation between both measurements has been accepted in some studies.35

It should be noted that this study collected information on PA that took place at home during leisure time only—a time during which behaviors tend to be less structured or prescribed than they are during fixed working hours.We found that participants generally did not exercise much.Our results showed that replacing SB time with time spent on daily life activities and structured exercises could significantly reduce the risk of all-cause dementia incidence and mortality.Specifically,various sports (such as swimming,cycling,and bowling) were associated with an 18% and 21%reduction in dementia incidence and mortality,respectively;light DIY saw corresponding reductions of 12% and 14%,and heavy DIY saw 7% and 12%.Some previous research limited PA to structured activities with the objective of improving physical fitness,while daily activities such as housework,farm work and walking for pleasure were not included.This could easily result in an underestimation of the total amount of activity in a day,making the influence of these very common forms of PA on dementia risk reduction unclear.36,37Our findings indicated that substituting sedentary time with even light DIY could significantly reduce the risk of dementia and associated death,but its replacement by walking for pleasure did not reduce the corresponding risk.The specific intensity of walking for pleasure was unclear but tended to be lower than the other activities in our study.18A prior report indicated that a slow walking speed was associated with an increased dementia risk,38which means that people who spend a certain amount of time walking for pleasure should consider intensity.Sports such as swimming,cycling,bowling,etc.may provide more benefits than walking.Previous prospective studies found that moderate-tovigorous PA could significantly reduce dementia risk,again indicating that intensity matters.39,40Interestingly,the subgroup analyses indicated that more vigorous exercise has more benefits for middle-aged individuals than for elderly individuals with respect to dementia development.

Regarding the gene-environment interaction,we observed a significant interaction between SB time and APOE genotype for risk of dementia incidence.We found that replacing sedentary time with structured exercise could significantly reduce the risk of AD incidence and mortality among APOE ε4 carriers but not among APOE ε4 noncarriers.These results are in line with those of previous studies that found greater PA to be associated with a lower brain amyloid burden41and dementia risk among APOE ε4 carriers.40

Our findings have clinical and public health implications for the primary prevention of dementia.These new insights into the benefits of reducing sedentary time by replacing it with PA challenge the common notion that there are few measures we can adopt to counter a genetic predisposition to dementia.Especially for APOE ε4 carriers,it may be good clinical advice to adopt a more active lifestyle with reduced SBs and a concomitant increase in daily life activity (e.g.,pruning,watering the lawn,weeding,lawn mowing,and purposeful exercise,such as swimming,bowling,and cycling).From a public health perspective,translating epidemiological findings into practice by applying specific types of PA in daily life is feasible and hence well-received by the general population.Leisure-time SB and PA are already common components of every individual’s life,so implementation is just a matter of time redistribution.Since it is relatively easy and cost-effective,replacing sedentary time with PA should be a go-to option for the primary prevention of dementia in clinical setting.

An increasing body of evidence suggests that PA could reduce the risk of vascular disease;and,at the metabolic level,it is associated with weight loss,lower blood pressure,and lower blood cholesterol.42Hence,it is not surprising to find that reallocating 30 min of SB time to PA was associated with a decreased risk of VD.It is rather exciting to observe that sitting less and moving more could result in a significant reduction in risk for AD and AD death as well.Multiple mechanisms may account for these benefits.PA is often performed in groups,thereby creating social networks that enhance social engagement.Social engagement protects individuals from loneliness,which is a strong risk factor for AD.43In addition,habitual exercise could increase brain-derived neurotrophic factors and promote synaptic plasticity and hippocampal neurogenesis,all of which have been linked to cognitive improvements.44Finally,regular PA has been shown to attenuate not only inflammation but also oxidative stress in the brain by improving the expression of several antioxidant enzymes45and modulating the production and activity of amyloid-β-degrading enzymes while inhibiting the amyloidogenic pathway.46

Our study has the following strengths:a large cohort design,consistent information about variables collected,use of an isotemporal substitution model,and most importantly,consideration of genetic risks.From a public health perspective,the epidemiological findings are easy to understand and translate into practice.However,this study also presents several potential limitations.First,the observational nature of the current study hampers the exploration of causality.18Second,we used a single and self-reported measure of both SB and PA rather than objective (accelerometry) data,meaning it was prone to recall bias.Since we did not include changes in time of SB and PA during follow-up,there may also be some degree of classification error.However,as mentioned in previous studies,47the true association could be toward the null and thus underestimated due to potential exposure misclassification.Third,because of the limitations of the questionnaire,only time spent watching TV,using the computer,and driving were recorded,instead of all sedentary hours.The objectives of SB can have varied effects on the brain.For this reason,leisure-time SBs were our primary interest,rather than those SBs that take place at work and may be more likely to stimulate the brain.Studies using compositional data analyses that record all activity time for each 24-h day are warranted in the future.Fourth,categorizing PA into types rather than according to metabolic equivalents may be culturally sensitive,and the accuracy could be less than objective.Fifth,these findings were based on hypothetical modeling of existing cohort data;although isotemporal substitution might be a more realistic approach,it is still just a mathematical technique and cannot substitute for experimental evidence.Last,since the UK Biobank cohort was restricted to volunteers with European ancestry and a relatively high socioeconomic background,representation of the general population is limited.Therefore,further research utilizing well-designed trials among more diverse populations is warranted.

5.Conclusion

This prospective population-based study found that leisuretime SB was positively associated with the risk of dementia incidence and mortality,and that replacing sedentary time with a short duration of PA was associated with a decreased risk of dementia.Our findings provide feasible and practical alternatives for the general population to reduce their time spent in SBs with an eye toward preventing or delaying dementia development and even its related death.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 77740.This study was supported by Shanghai Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau (2020074),Clinical Research Plan of SHDC(SHDC2020CR4006),Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital(YBKA201909),Innovative research team of high-level local universities in Shanghai (SHSMU-ZDCX20212501),Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2022XD017).The funders played no role in the design or conduction of the study;in the collection,management,analysis,or interpretation of the data;or in the preparation,review,or approval of the article.

Authors’contributions

NW and YL conceptualized this paper;YS and CC wrote the manuscript,researched data,and reviewed and edited the manuscript;LQ reviewed and edited the manuscript;YY,HZ,JZ,and XT contributed to data acquisition and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2022.11.005.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2023年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2023年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Impact loading in female runners with single and multiple bone stress injuries during fresh and exerted conditions

- Are EPB41 and alpha-synuclein diagnostic biomarkers of sport-related concussion?Findings from the NCAA and Department of Defense CARE Consortium

- Factors and expectations influencing concussion disclosure within NCAA Division I athletes:A mixed methodological approach

- Effects of contact/collision sport history on gait in early-to mid-adulthood

- Refinement of saliva microRNA biomarkers for sports-related concussion

- Lacrosse-related injuries in boys and girls treated in U.S.emergency departments,2000-2016