Nonpharmaceutical interventions effectively reduced influenza spread during the COVID-19 pandemic

Yuan Yuan, Yan Li, Jiang-shan Wang, Ye-cheng Liu, Jun Xu, Hua-dong Zhu, Lu-zhao Feng

1 Emergency Department, State Key Laboratory of Complex Severe and Rare Diseases, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Science and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100005, China

2 School of Population Medicine & Public Health, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences/Peking Union Medical College,Beijing 100730, China

Seasonal influenza, which is transmitted by droplets and direct contact, is a global public health issue that causes an average of 2.5 excess influenza-like illness (ILI) consultations per 1,000 person-years in China.[1]Nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) against droplet and direct contact transmission, including social distancing measures and personal protective measures, are recommended to reduce the spread of disease.Social distancing measures comprised isolating ill persons, quarantining exposed persons, school and workplace closures, and avoiding crowds.Personal protective measures included hygiene, respiratory etiquette,and face masks.[2]In December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) started to spread, and China introduced NPIs to address the pandemic in January 2020.These NPIs could also help reduce the spread of other respiratory diseases,such as seasonal influenza.[3]In the second half of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was gradually brought under control.Production, transport, and schools were returning to normal,while citizens were still required to wear masks in public.Cases of influenza also reappeared.This study compared the ILI percentage (ILI%), laboratory (LAB)-positive rate,incidence rate, and effective reproductive number (Rt) of influenzas from 2019 to 2022 to clarify the change in seasonal influenza spread after the COVID-19 outbreak.

METHODS

In this study, data were obtained from China’s National influenza Center, which publishes the ILI% and the confirmed cases of influenza weekly in both South and North China.We also extracted the number of domestic tourists, passenger transport volume, unemployment rate,Engel’s coefficient, and total retail sales of consumer goods from the National Bureau of Statistics and the influenza vaccination rate from the 2022 National Vaccines and Health Conference to estimate their association with the incidence rate.We believe that these data can reflect the degree of openness of society.In China, seasonal influenza has peak activity from November to March of the following year.[4]Therefore, each epidemic season is defined as 1 November to 31 March of the following year.

We used several indicators to reflect influenza activity,namely, ILI%, LAB-positive rate, incidence rate estimated by the ILI+ proxy and Rt.ILI+ proxy, which was calculated as ILI% multiplied by the LAB-positive rate, had a better linear correlation with the incidence of influenza.[5,6]The weekly ILI+ proxy values were interpolated to the daily ILI+proxy values using splines.Then, Rt was calculated using the R package EpiEstim (www.r-project.org), assuming a mean serial interval of 2.85 days and a standard deviation of 0.93 days.[3]

The weekly changes in the number of patients diagnosed with seasonal influenza and ILI% in the epidemiological years 2019–2020, 2020–2021, and 2021–2022 were compared.The correlation between the incidence rate and socioeconomic data was also analyzed.The Chi-square test, paired-differencettests, and Spearman’s rank correlation were used in the analyses.AP-value <0.001 was considered statistically significant, and all analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM Corp., USA).

RESULTS

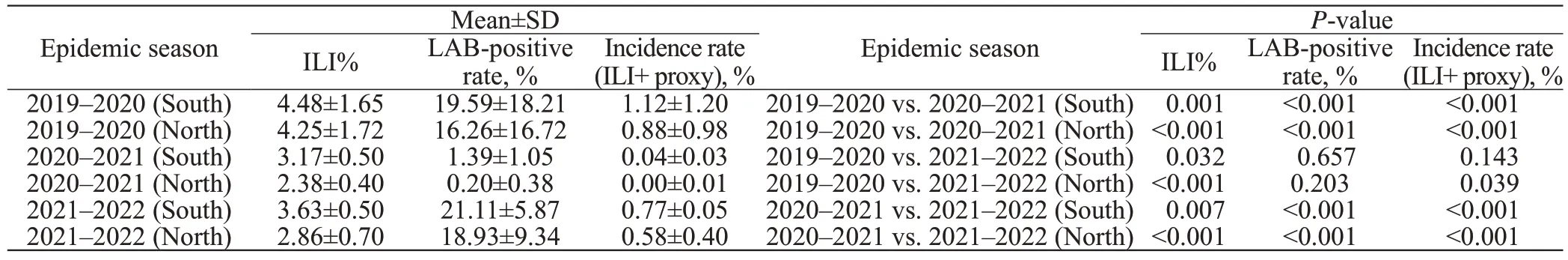

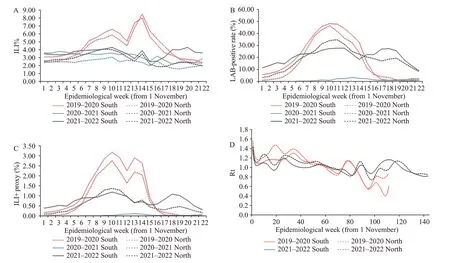

The ILI%, LAB-positive rate, and incidence rate for each year are listed in Table 1.Compared with 2019–2020 and 2021–2022, the incidence rate decreased by 94%–100% in 2020–2021.Both ILI% and the LAB-positive rate were much lower in 2020–2021 (P≤0.001) than in the other years, while there was no significant difference in the LAB-positive rate and incidence rate between 2019–2020 and 2021–2022 (Figures 1 A–D).By the end of the epidemiological year 2019–2020, Rt had fallen below 1,indicating that influenza was no longer being transmitted.However, in 2021–2022, Rt remained relatively flat throughout the epidemiological season.At the end of March 2022, Rt still fluctuated near 1, indicating that the influenza virus could still be transmitted.

We also explored the relationship between the incidence rate and vaccination rate, number of domestic tourists,passenger transport volume, unemployment rate, Engel’s coefficient, and total retail sales of consumer goods and found no statistical correlation (P>0.05) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

At the end of January 2020, China adopted NPIs to prevent the spread of COVID-19, which comprised personal protective measures and social distancing measures.[7]Unlike the epidemiological year 2019–2020, there was no influenza transmission in 2020–2021.This suggests that COVID-19 preventive measures reduced the spread of influenza.A studyhas proven that the number of COVID-19 cases could have been decreased significantly (by 95%) if NPIs had been initiated 3 weeks earlier than they were adopted.[8]We suspect that the same holds true for seasonal influenza.Despite the gradual weakening of social isolation measures in China from the end of 2020, the incidence of influenza remained low even in early 2021 because the NPIs were still in place at the beginning of the 2020–2021 epidemiological season.

Table 1.differences in ILI%, LAB-positive rate, and incidence rate of influenza in epidemic season

Table 2.Correlation of incidence rate with vaccination rate and social openness

Figure 1.Seasonal influenza activity during the epidemiological year 2019–2020 (red) compared with the epidemiological years 2020–2021 (black)and 2021–2022 (blue).A: ILI%; B: LAB-positive rate; C: ILI+ proxy, which represents the incidence rate; D: daily effective reproductive number of seasonal influenza in the epidemiological year 2019–2020 (red) compared with that in 2021–2022 (black).ILI: influenza-like illness; LABpositive rate: laboratory-positive rate; Rt: reproductive number.

The results showed that the overall incidence rate in 2021–2022 did not differ from that in 2019–2020.Some studies of NPIs discussed the difference between social distancing measures and personal protective measures.It is widely accepted that closing schools can reduce the spread of influenza.[9]With schools and businesses reopening in 2021, increased social contact could be the reason for the renewed spread of influenza.Although there was no statistically significant association between vaccination and incidence, it is important to note that the influenza vaccination rate in China in 2021 decreased by 22% compared with 2020 (3.3% vs.2.5%, respectively).People may have paid less attention to influenza vaccination during mass vaccination against COVID-19.

The results of this study suggested that personal protective measures alone cannot reduce the incidence of influenza.However, we believe that personal protective measures were effective in controlling the spread of respiratory diseases.The guidelines of the European Center for Disease Control and Prevention[10]state that the objectives in controlling a pandemic are delaying and flattening the epidemic curve, reducing the height of its peak, and spreading cases over a longer time period.These measures could reduce the burden on healthcare systems,provide time to prepare for hospitalizations, better manage cases, and even develop vaccines.From this perspective,the patterns of the influenza epidemic in 2021–2022 meet the objectives of epidemic control.

This study summarizes the changes in influenza from the beginning to two years after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic.NPIs have changed the transmission patterns of respiratory disease, and the healthcare system in China,especially emergency doctors in charge of fever clinics, must be prepared for these changes.

Limitations

This study analyzed the correlation between influenza prevalence and NPIs during COVID-19 epidemics.However, there was no implementation rate of each of the epidemic prevention measures, such as mask wearing.The relationship between specific protective measures and morbidity could not be analyzed and needs further research.

CONCLUSION

The NPIs adopted in China during the COVID-19 pandemic effectively reduced the spread of seasonal influenza.Social distancing measures combined with personal protective measures appear to be more useful than personal protective measures alone.

Funding:The study was supported by National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-D-005) and National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-B-109).

Ethical approval:This study used publicly available data and did not involve personal information or intervention.The Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital exempted the ethical review of this study (I-23ZM0005).

Conflicts of interest: None.

Contributors:YY proposed the study and wrote the manuscript.All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

World journal of emergency medicine2023年3期

World journal of emergency medicine2023年3期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Most patients with non-hypertensive diseases at a critical care resuscitation unit require arterial pressure monitoring: a prospective observational study

- Over-expression of programmed death-ligand 1 and programmed death-1 on antigen-presenting cells as a predictor of organ dysfunction and mortality during early sepsis: a prospective cohort study

- Effects of continuous renal replacement therapy on inflammation-related anemia, iron metabolism and prognosis in sepsis patients with acute kidney injury

- Effects of early standardized enteral nutrition on preventing acute muscle loss in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with mechanical ventilation

- Development and validation of a predictive model for the assessment of potassium-lowering treatment among hyperkalemia patients

- The relationship between physical activity in early pregnancy and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy:a cohort study in Chinese women