effect of post-rewarming fever after targeted temperature management in cardiac arrest patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Guang-qi Guo, Yan-nan Ma, Shuang Xu, Hong-rong Zhang, Peng Sun

Department of Emergency Medicine, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China

KEYWORDS: Cardiac arrest; Target temperature management; Post-rewarming fever; Rebound hyperthermia

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrest (CA) is an important global public health issue and is associated with high mortality.[1,2]Inhospital CA occurs in more than 290,000 adults each year in the United States.[3]Cardiopulmonary resuscitation(CPR) is an effective emergency intervention for CA.[4]After CA treatment and the successful return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), the neurological outcome of patients tends to be undesirable.[5]Approximately 50% of survivors suffer brain injury and consequent different severities of neurologic disability.[6]Targeted temperature management (TTM), also known as “temperature control”, which maintains the patient’s temperature from 32 ℃ to 36 ℃ for at least 24 h, was recommended by international guidelines to attenuate brain injury and improve the neurological outcome.[7,8]The development of fever before TTM occurs frequently and has previously been found to be associated with unfavorable outcomes.[9,10]With the implementation of TTM in recent years, post-arrest fever in the immediate period can be prevented.However, an important study,the TTM-2 trial, suggested that TTM did not lead to a lower mortality by 6 months than targeted normothermia in patients with coma after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest(OHCA).[11]Although recent guidelines suggested that there was insufficient evidence to provide advice for the implementation of TTM after CA.[8,12]Notably, the fever can also occur after the rewarming period following TTM and affect the outcome of CA patients.[13-25]In this study, we mainly focus on the fever in the patients who completed TTM.

Post-rewarming fever (PRF), or rebound hyperthermia (RH), was observed in many patients who received TTM.[13-26]PRF was defined as a phenomenon of increased body temperature (>38.0 ℃ or greater) after the rewarming period following TTM.[14-22,24,25]According to the European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ERC-ESICM)guidelines, actively preventing fever (defined as body temperature >37.7 ℃) for at least 72 h is recommended for comatose patients after CA.[8]However, the influence of temperature control strategies after rewarming remains unclear.There is no sufficient evidence to support temperature control in CA patients after rewarming following TTM.[8,27]Previous studies on the influence of PRF on neurological outcomes have shown conflicting results.Some studies have suggested that PRF is related to unfavorable neurological outcomes.[15,18,24,25]However,recent studies have indicated that PRF may be a symbol of good neurological outcome.[19,20,28]Therefore, the clinical significance of PRF should be better understood.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to investigate whether PRF could have an impact on clinically relevant outcomes, including neurological outcome and mortality, in patients suffering from CA.Meanwhile, this meta-analysis may provide a better understanding of temperature control strategies in patients who completed TTM.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis —Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines.[29]The protocol of this study was registered at www.inplasy.com(INPLASY202240052).

Data sources and search strategies

We performed the literature retrieval up to March 13,2022, in the EMBASE, PubMed, and Cochrane Central databases using the following Medical Subject Headings(MeSH) terms: “cardiac arrest”AND “targeted temperature management”AND (“fever”OR “hyperthermia”)(supplementary Table 1).

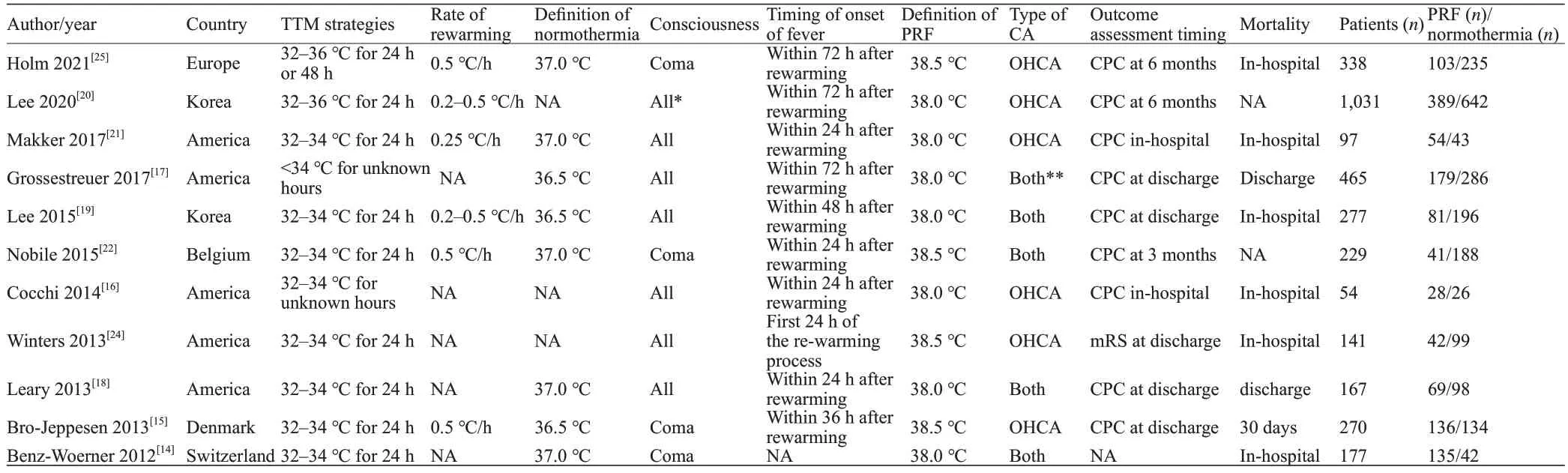

Table 1.Summary of the included studies

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies were selected for the meta-analysis according to the following requirements: (1) the participants of the study were adult patients with CA; (2) the TTM therapy was involved in the research; (3) the study observed and defined the phenomenon of PRF (body temperature >38.0℃ or greater); (4) the data about neurological outcome and mortality of patients who suffered PRF were available; (5) the studies were cohort studies or randomized controlled trials(RCTs); and (6) the study articles were written in English.

The studies were excluded if the following conditions were met: (1) the full text of the article could not be accessed; (2) only the abstract of articles was accessible;(3) only a citation or report on the study could be found in another publication; and (4) the neurological outcome and mortality data were not available.

We reviewed the articles that conformed to the abovementioned criteria and extracted the relevant data about neurological outcome and/or mortality.In this meta-analysis,the definition of unfavorable neurological outcome was Glasgow-Pittsburgh cerebral performance category (CPC)> 2 or modified Rankin Scale (mRS) >3.[30,31]The primary outcome is unfavorable neurological outcome at discharge or at the end of the follow-up period.The secondary outcome is the mortality rate in the hospital or at the end of the followup period.

Research selection and data extraction

Two independent researchers (GQG and YNM) screened all the accessible articles based on the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria and extracted the relevant data of the studies.In the progress of the data extraction, the arising controversies about studies from two researchers were discussed with a third researcher (SX).The first author’s first name, the study’s year, the study’s host country, the study design type, the study period, the methods of TTM, the number of PRF patients and control patients, the definition of PRF, the type of neurological outcome assessment and mortality of the original studies were all extracted.

Risk of bias assessment

No RCTs were selected in this meta-analysis.The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the risk of bias (ROB).[32]The NOS had a total score of 9 points and included cohort selection, cohort comparability, and outcome evaluation.Studies that scored at least 6 points were included in the meta-analysis (supplementary Table 2).

Statistical analysis

The degree of variability and heterogeneity of the meta-analysis were assessed usingI2andPvalues.WhenI2was 50%, 51%–75%, or >76%, it was classified as low, moderate, or high heterogeneity, respectively.For high heterogeneity, the random effects model was used to calculate the merged odds ratios (ORs) and 95%confidence intervals (CIs), while the fixed effect model was used for low or moderate heterogeneity.The study model’s robustness was tested by sensitivity analysis.In this study, Review Manager 5.4 software was used to conduct statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Screening of relevant research

After electronic database searches and bibliographical inspections, 330 records were screened according to the retrieval strategies.Forty-two records were duplicated, and 277 of the remaining records were excluded on account of title, abstract, study design, unavailable data and other factors.As a result, 11 studies were selected for this metaanalysis (supplementary Figure 1).[14-22,24,25]

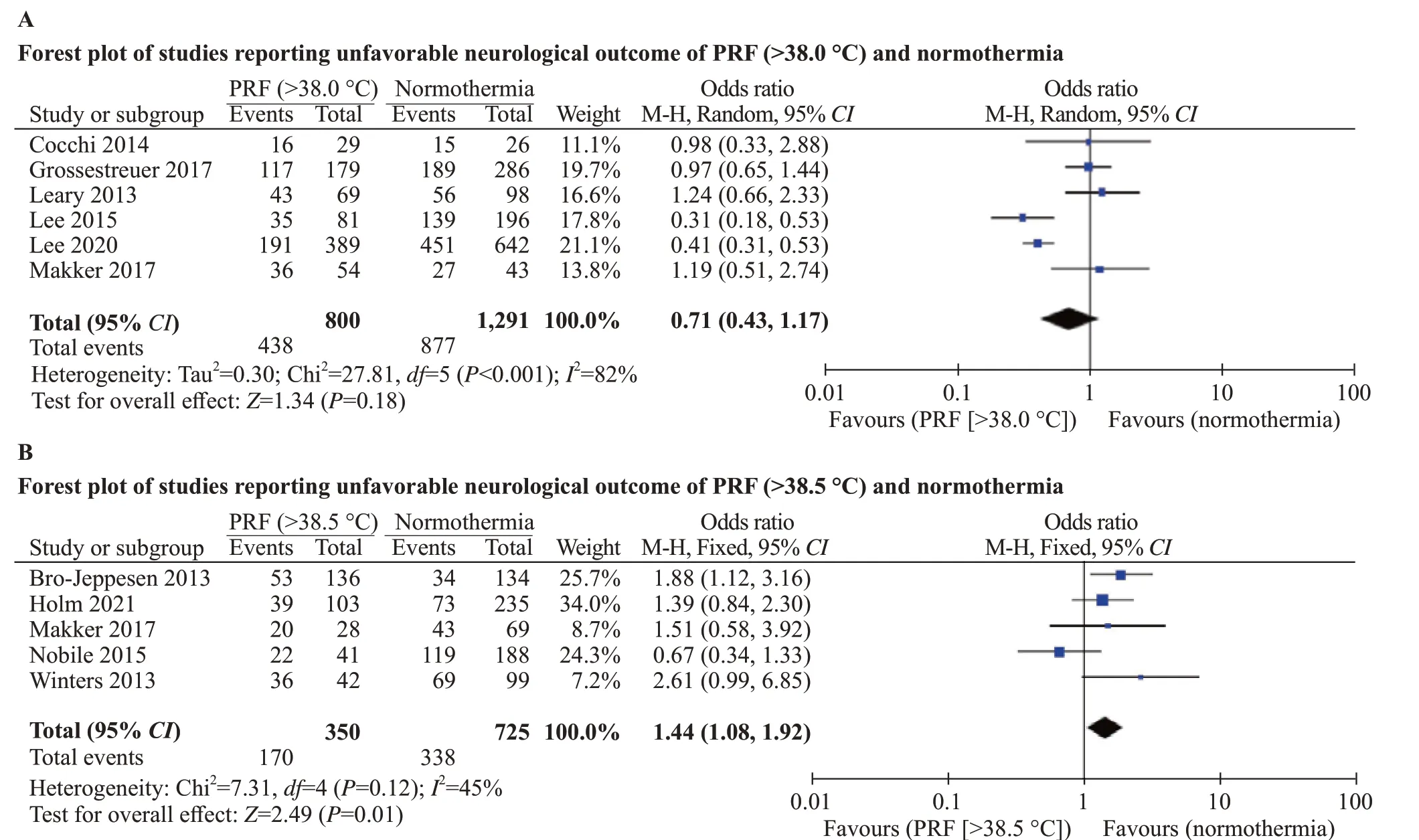

Figure 1.Forest plot of studies reporting unfavorable neurological outcomes of PRF and normothermia.

Study characteristics

A total of 3,246 CA patients were selected in this meta-analysis, of whom 1,257 patients developed PRF and 1,989 patients maintained normothermia.The 11 included studies had different definitions of PRF.Eligible studies included seven articles that defined PRF as a body temperature >38.0 ℃ after TTM.[14,16-21]Four articles defined PRF as >38.5 ℃ after TTM.[15,22,24,25]The neurological outcome of patients was assessed in 10 studies,[15-22,24,25]while mortality was calculated in 9 studies.[14-19,21,24,25]More details and characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Assessing the risk of bias

The 11 included studies were observational cohort studies,and no RCTs were selected for this meta-analysis.The scores of all the eligible cohort studies were greater than or equal to 6 points based on the NOS (supplementary Table 2).

Primary outcome—unfavorable neurological outcome

Ten of the included studies reported the neurological outcome of patients.Six studies defined PRF as >38.0°C,[16-21]and four studies defined PRF as >38.5 °C.[15,22,24,25]The neurological outcome was assessed at different timepoints in the respective original studies.We extracted the timing of neurological outcome data in accordance with Table 1.

Articles defining PRF as >38.0 °C and >38.5 ℃ were selected for different meta-analyses of PRF and neurological outcomes.Six articles defined PRF as >38.0 °C[16-21]and analyzed it with a random effects model.Analysis of these six articles showed that PRF (> 38.0 °C) had no significant effect on the unfavorable neurological outcome of CA patients (OR0.71; 95%CI0.43–1.17;I282%) (Figure 1A).

Four articles defined PRF as >38.5 °C and investigated the effect of PRF on neurological outcome.[15,22,24,25]One study conducted by Makker et al[21]defined PRF as >38.0 °C but contained a subgroup that investigated the relationship between PRF >38.5 °C and the neurological outcome of CA patients.We used the fixed effects model to analyze data from the five studies.The results showed that PRF with higher body temperature (PRF >38.5 ℃) had a significant association with unfavorable neurological outcomes in CA patients (OR1.44, 95%CI1.08–1.92,I245%) (Figure 1B).

Secondary outcome—mortality

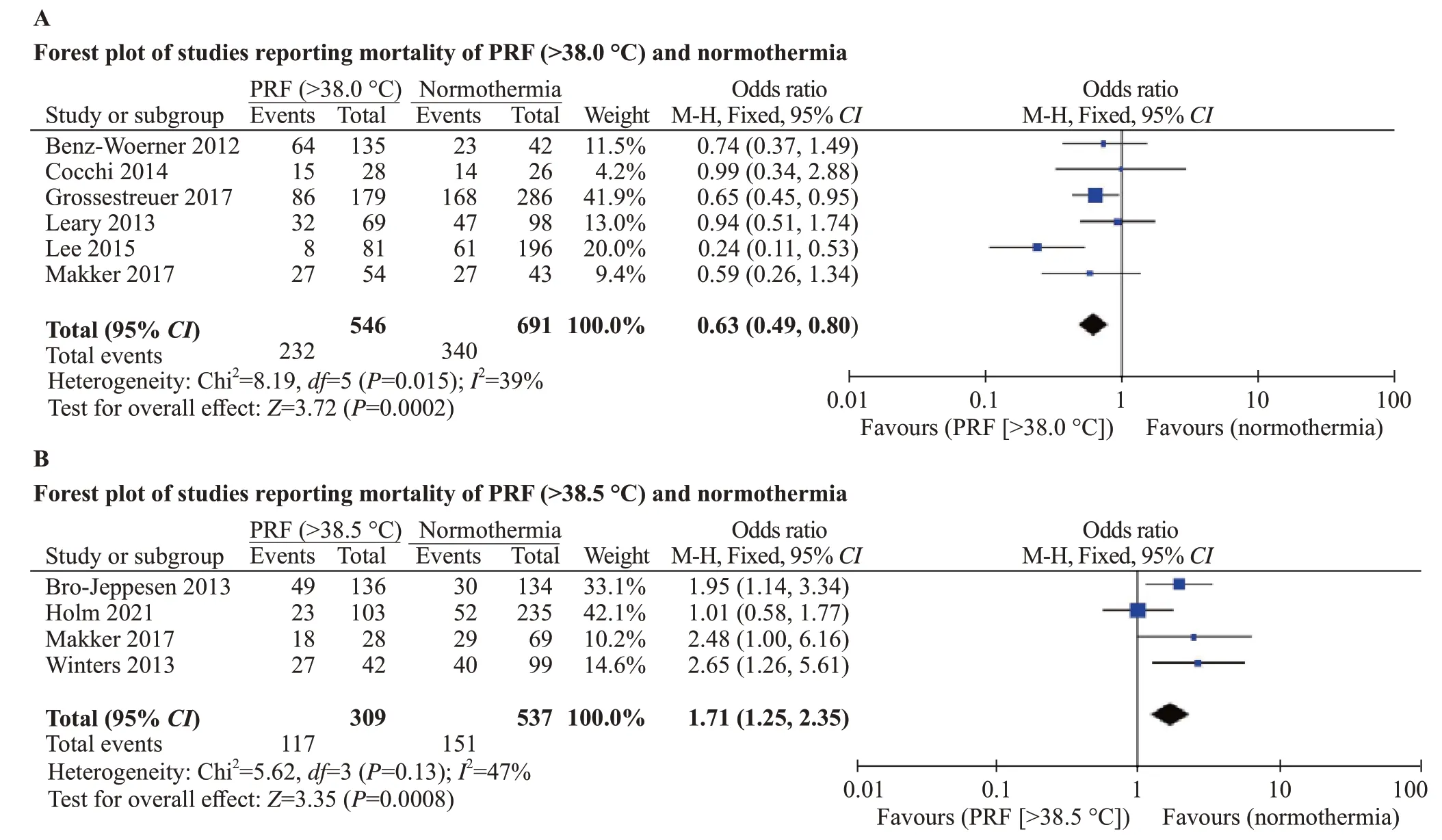

Mortality data were available in nine of the studies included in this meta-analysis.Six studies defined PRF as>38.0 °C,[14,16-19,21]and three studies defined PRF as >38.5°C.[15,24,25]We examined the six studies (PRF >38.0 ℃)using a fixed effect model.The results suggested that PRF(body temperature >38.0 ℃) was associated with lower mortality (OR0.63, 95%CI0.49–0.80,I239%) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.Forest plot of studies reporting mortality of PRF and normothermia.

Three studies investigated the association between PRF >38.5 ℃ and mortality.[15,24,25]One study conducted byMakker et al[21]contained a subgroup that investigated the effect of PRF >38.5 ℃ on mortality.A fixed-effect model was used to analyze the five studies.The results showed that PRF with higher body temperature was associated with higher mortality (OR1.71, 95%CI1.25–2.35,I247%)(Figure 2B).

Sensitivity analysis

None of the 11 studies were evaluated as having a high risk of bias.Therefore, sensitivity analysis was performed by removing the included studies one by one to see how they affected the pooledOR, 95%CIand heterogeneity.The results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in supplementary Tables 3–6.The studies conducted by Lee et al,[19]Nobile et al,[22]and Holm et al[25]influenced the heterogeneity in their respective analyses (supplementary Tables 4–6).However, these studies had no effect on the robustness of the results.Sensitivity analysis showed that the results of this metaanalysis had good robustness.

DISCUSSION

In this meta-analysis, 11 studies involving 3,246 patients analyzed the relationship between PRF and the prognosis of patients.The results of this meta-analysis suggest that CA patients who experienced PRF (>38.0 ℃) after TTM had similar neurological outcomes and lower mortality than normothermia patients.However, patients who experienced PRF, defined as a stricter body temperature (>38.5 °C), were associated with worse neurological outcomes and higher mortality.

The analysis of PRF >38.0 ℃ and neurological outcome had high heterogeneity, and sensitivity analysis was conducted to test the robustness of the merger results in the analysis (supplementary Table 3).The reasons for the high heterogeneity varied, such as the type of CA,the design of the TTM plan and the timing of outcome acquisition.It is noteworthy that the onset time of PRF may affect heterogeneity.The study conducted by Lee et al[20]observed the development of PRF in different periods after rewarming and divided the PRF patients into three subgroups.The results indicated that PRF occurring within 24 h after rewarming (but not within 24–48 h or 48–72 h)was associated with favorable neurologic outcomes and decreased mortality.This study suggests that the onset time of PRF may also be a critical factor affecting the prognosis of CA patients.It is difficult to avoid heterogeneity since the original studies had different research protocols for PRF.

A concise meta-analysis conducted by Makker et al[33]found that PRF (both >38.0 ℃ and >38.5 ℃) was associated with a significantly worse neurological outcome, which was not consistent with the present results.Possible reasons for the above discrepancy may be the inclusion of emerging studies.The studies that have emerged in recent years suggested that PRF may not be associated with unfavorable neurological outcomes.Several studies have even suggested that PRF is a favorable symbol for CA patients.[19,20,28]

This meta-analysis reveals that PRF has different effects on the mortality of CA patients when the definition of PRF is diverse.When the cutoff temperature of PRF was lower(>38.0 ℃), patients with moderate fever (38.0–38.5 ℃) were included in the study.Several included studies suggested that moderate PRF have no effect on the prognosis of CA patients and tended to be associated with favorable outcomes.[17,19,20]One probable explanation proposed by Murnin et al[34]was that more severe brain injury impacts the function of hypothalamus and thermoregulation, since the hypothalamus is not one of the especially vulnerable regions to ischemia-reperfusion injury.PRF reflects higher heat generation and preserved thermoregulatory function, which suggests less severe brain injury than that in patients with lower post-rewarming body temperatures.[27]This explanation was supported by the study conducted by Lee et al[19]that the prevalence of PRF was associated with favorable CA prognosis indicators, such as younger age and lower SOFA scores.

In the present study, PRF with a stricter definition(body temperature >38.5 ℃) was associated with worse neurological outcome and higher mortality.Fever, as is well known, has a significant association with poor prognosis in patients with brain injury.Before TTM was recommended by the guidelines and widely used as a clinical strategy, fever was a marker for worse outcomes in CA patients.[35]In anin vitrostudy, the prevention of PRF aggravated apoptosis of cells and release of inflammatory factors.[36]Meanwhile,post-cardiac arrest syndrome (PCAS) is characterized by multi-organ ischemia-reperfusion injury and the production of inflammatory cytokines, which can cause fever in CA patients.[37]These studies indicated that PRF was related to the activation of the inflammatory response and programmed cell death following ischemia-reperfusion injury caused by CA.This is a reasonable explanation for the relationship between severe fever and worse outcomes in CA patients who completed TTM.The study conducted by Grossestreuer et al[17]indicated that higher body temperature was linearly associated with increased mortality.

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that preventing fever after rewarming is necessary when the body temperature was >38.5 ℃.However, one study conducted by Kim et al[27]indicated that the implementation of controlled normothermia to prevent PRF was not associated with favorable neurological outcome.Although this study conducted by Kim et al[27]had some limitations, such as the nonstandard controlled normothermia protocols and the incomplete data of included patients, the results showed that the post-rewarming active temperature control could prevent the high fever after the rewarming period of TTM.

Most previous studies were focused on the clinical application of TTM, including optimal cooling temperature,[38]practical methods of cooling for temperature control[39]and rate of rewarming following TTM.[40]The guidelines rarely mention body temperature control strategies after the rewarming period.[8]In this meta-analysis, we focused on active body temperature management strategies after TTM.The results suggest that therapeutic intervention is necessary to prevent high fever after the completion of TTM.

The following are the advantages of this study: (1) this meta-analysis evaluated PRF after TTM in CA patients and assisted physicians in recognizing the clinical Effects of PRF and patient prognosis following ROSC; (2) the PRF group was divided into subgroups >38.0 °C and >38.5 °C so that physicians could better understand the severity of fever and make corresponding treatment decisions.

Nonetheless, the following are the limitations of this meta-analysis: (1) meta-analysis was a secondary analysis of original studies, and high heterogeneity caused by many reasons existed among different studies; (2) the TTM therapy methods of the included studies were different, which may contribute to the high heterogeneity.Therefore, more RCTs with standard TTM treatment are needed in the future to investigate the effect of PRF.

CONCLUSION

This study provides a specific understanding of the PRF phenomenon and suggests that PRF with a broader definition(body temperature >38.0 ℃) is associated with favorable neurological outcomes and lower mortality.However, PRF was associated with worse neurological outcomes and higher mortality when PRF was defined as >38.5 ℃.It is necessary to prevent fever after rewarming when the body temperature of CA patients is >38.5 ℃.

Funding:This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072137; 81571866).

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributors:GQG conceived the study concept and design and was involved in the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

All the supplementary files in this paper are available at http://wjem.com.cn.

World journal of emergency medicine2023年3期

World journal of emergency medicine2023年3期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Most patients with non-hypertensive diseases at a critical care resuscitation unit require arterial pressure monitoring: a prospective observational study

- Over-expression of programmed death-ligand 1 and programmed death-1 on antigen-presenting cells as a predictor of organ dysfunction and mortality during early sepsis: a prospective cohort study

- Effects of continuous renal replacement therapy on inflammation-related anemia, iron metabolism and prognosis in sepsis patients with acute kidney injury

- Effects of early standardized enteral nutrition on preventing acute muscle loss in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with mechanical ventilation

- Development and validation of a predictive model for the assessment of potassium-lowering treatment among hyperkalemia patients

- The relationship between physical activity in early pregnancy and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy:a cohort study in Chinese women