Psychiatric comorbidities in children and adolescents with chronic urticaria

George N. Konstantinou · Gerasimos N. Konstantinou

Abstract Background Chronic urticaria (CU) has been shown to impact patients' quality of life negatively and may coexist with psychiatric disorders.We systematically reviewed the published evidence of comorbid psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with CU.Methods A systematic review of studies published until February 2022 in PubMed,Google Scholar,and Scopus was performed.An a priori set of inclusion criteria was predefined for the studies to be included: (1) clear distinction between urticaria and other allergies;(2) precise distinction between acute and CU;(3) participants younger than 18 years old,exclusively;(4) use of appropriate standardized questionnaires,psychometric tools,and standard diagnostic nomenclature for the mental health and behavioral disorders diagnosis;and (5) manuscripts written or published in the English language.Results Our search identified 582 potentially relevant papers.Only eight of them satisfied the inclusion criteria.Quantitative meta-analysis was not deemed appropriate,given the lack of relevant randomized control trials,the small number of relevant shortlisted,the small sample size of the patients included in each study,and the remarkable heterogeneity of the studies' protocols.Conclusions The included studies suggest an increased incidence of psychopathology among children and adolescents with CU as opposed to healthy age-matched individuals,but the data are scarce.Further research is required to clarify whether psychopathology is just a comorbid entity,the cause,or the consequence of CU.Meanwhile an interdisciplinary collaboration between allergists/dermatologists and psychiatrists is expected to substantially minimize CU burden and improve patients'quality of life.

Keywords Adolescents · Children · Chronic urticaria · Psychiatry · Psychopathology · Quality of life

Introduction

Urticaria is a common condition characterized by transient erythematous and edematous plaques or papules with circumscribed erythematous borders and central clearing,known as wheals or hives.These lesions are usually accompanied by pruritus,they may have different sizes,and up to 60% of the patients may report coexisting angioedema at least once in their lifetime.Recurrent urticarial lesions,appearing most of the days of the week for at least six weeks,define chronic urticaria (CU) [1,2].Chronic spontaneous urticaria refers to CU with no specific cause or trigger and is responsible for almost 80% of all CU cases [3].Despite its benign nature,this ailment may cause frustration for patients and their families.In addition,it is a diagnostic and therapeutic conundrum for physicians due to the persistent symptoms,prolonged duration,and unknown origin [4].The symptoms can persist for months and are a significant source of distress that negatively impacts patients' quality of life (QoL)and may account for sleep disorders,negative self-image,functional disability,and adverse emotions [5-7].Interestingly,meta-analytic findings support the high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders in adult patients with CU [8].However,the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms that may connect or relate to these clinical entities have not yet been identified,given CU's still poorly understood pathogenesis [9].

In children,the prevalence of CU ranges from 0.1%to 3.0% [10].It is unclear whether the underlying pathophysiology is the same as in adults.However,physical stimuli (like cold,heat,mechanical stimuli,and sun exposure),viral infections,medication intake,and food ingestion seem to be among the most common triggers[11-13].The QoL of children with CU is impaired from a greater to a lesser degree,depending on the disease severity.The recurrence of the symptoms can represent a heavy burden for them and their families (or their caregivers).As a chronic and distressing disorder,the emergence or the coexistence of psychological burdens is of no surprise in this unique population,and daily activities such as school performance,sleep,personal care,and peer interaction can be negatively impacted [13].

Limited studies have investigated the comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with CU.Therefore,in the absence of any systematic review in the extant literature related to this field,we performed a systematic review to examine the incidence of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents with CU,any potential associations that may exist,and the role of the psychiatric interventions in the control and treatment of CU.

Methods

This systematic literature review was conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [14].The protocol of this systemic review has been registered on PROSPERO (CRD42019123008).An a priori set of inclusion criteria was predefined.An a priori set of inclusion criteria was predefined for the studies to be included: (1) clear distinction between urticaria and other allergies;(2) precise distinction between acute and CU;(3) participants younger than 18 years old exclusively;(4) use of appropriate standardized questionnaires,psychometric tools,and standard diagnostic nomenclature for the mental health and behavioral disorders diagnosis (i.e.,the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and related health problems,and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders);and (5) manuscripts written or published in the English language to precisely follow and record the relevant nomenclature.Unpublished research and research in progress were not included.The references of eligible publications were scrutinized to identify additional possible studies.

Type of studies and participants

Eligible studies included randomized clinical trials (RCT),controlled clinical trials,cohort studies,case-control studies,case series,and case reports investigating the comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and CU in children and adolescents under 18 years old.Studies that included both adult and pediatric patients were excluded.

Search strategies for identification of studies

A systematic review of studies published until February 2022 in PubMed (for MEDLINE database),Google Scholar,and Scopus was performed.Our relevance search algorithm consisted of a combination of MeSH terms and keywords:urticaria AND (psych* OR depress* OR anxi* OR attention OR somatic OR eating OR suicid* OR neurodevelopment*OR tic OR affective OR bipolar OR mood OR schizophr*OR sleep OR obsess*) AND (child* OR adolescen*).

Data collection

The two authors independently conducted the literature review,assessed all titles and abstracts,extracted all data,and assessed quality.The full manuscripts of all potentially eligible studies were assessed for eligibility against the predefined inclusion criteria.A manual search was also performed on the reference list from these articles to identify other potentially relevant studies missed in the data-based search.All the included studies were discussed and approved by both authors.

The primary outcome was to examine the prevalence and the type of psychiatric disorders existing as comorbidities in children and adolescents with CU.The secondary outcome was the evaluation of potential psychiatric interventions applied.The outcome terminologies used were those reported in the original publications.

Results

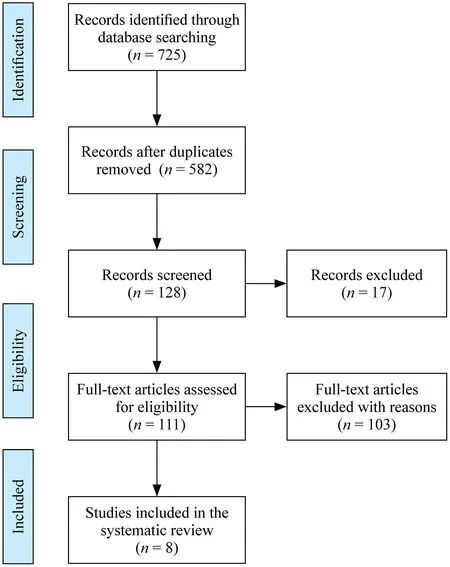

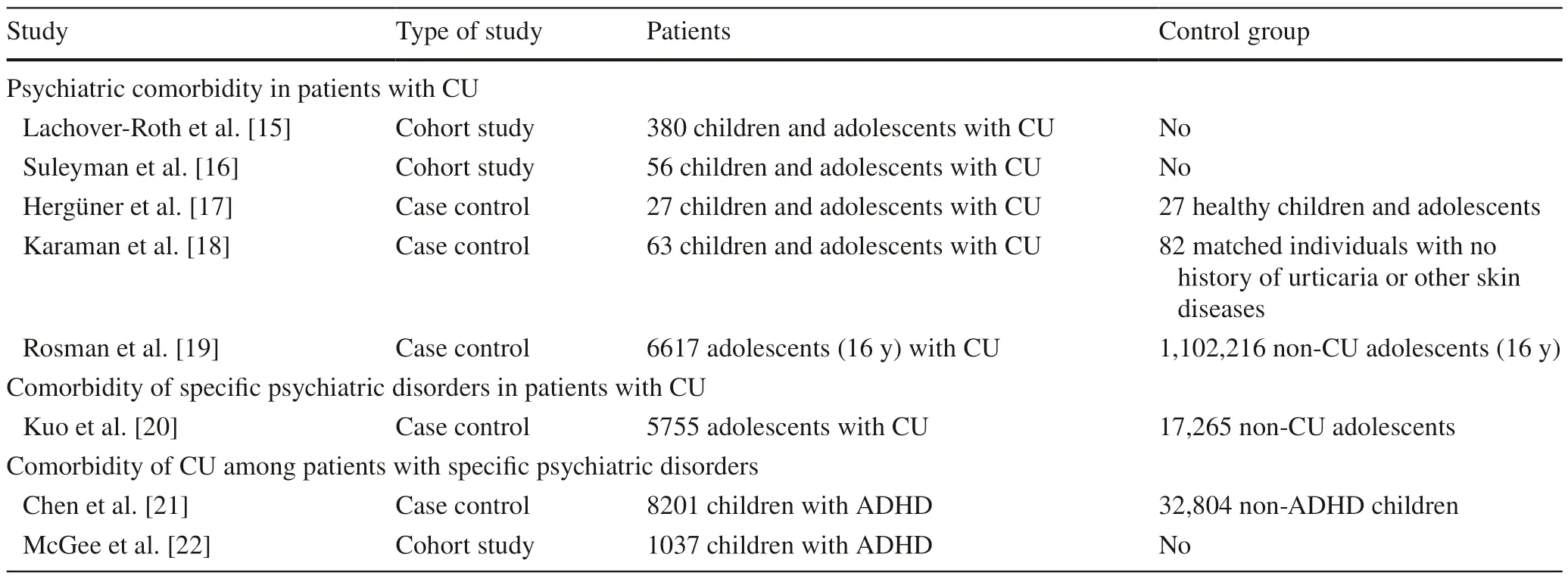

After excluding duplicated articles,our initial search identified 582 potentially relevant papers (Fig. 1).However,only eight satisfied our inclusion criteria (Table 1).Most studies were based on retrospective reviews,and no RCTs were found.There was wide variability among the studies regarding their design,the recruited participants (demographic variables,ethnicity,gender),the psychometric tools,and the diagnostic criteria used.It should also be noted that among the few studies identified in the extant literature examining the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with CU,there are studies that include both pediatric and adult populations in a single group without quoting each age group separately or specifically for CU.These studies were not included in this systematic review.Quantitative metaanalysis was not deemed appropriate,given the lack of relevant randomized control trials,the small number of relevant shortlisted studies,the small sample size of the patients included in each study,the fact that not all different mental health disorders were assessed simultaneously among the CU children examined,and the remarkable heterogeneity of the studies' protocols.Of note,there is a lack of evidence suggesting an increased incidence of psychiatric comorbidities among more severe forms of CU.

Fig.1 Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaanalysis flow diagram of this study

Table 1 Psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents with chronic urticarial (n =8)

Psychiatric comorbidities (all) in children and adolescents with chronic urticaria (studies without a control group)

In a retrospective study from Israel,380 children and adolescents up to 18 years old diagnosed with CU were included and evaluated [15].Seven (2.8%) patients had comorbid psychiatric disorders,including depression,anxiety,bipolar disorder,and schizophrenia.Interestingly,all patients were diagnosed after the first CU episode.Previously,a Turkish study found an incidence of any psychiatric disorder of 69.6% (n=39) among 56 children and adolescents with CU[16].Notably,17.9% (n=10) of them had been diagnosed with more than one psychiatric disorder.

Psychiatric comorbidities (all) in children and adolescents with chronic urticaria (studies with a control group)

Another study recruited 27 children and adolescents with CU and 27 age-and sex-matched healthy individuals as a control group [17].Nineteen of the patients with CU had at least one psychiatric disorder,whereas this was the case in eight individuals in the control group(70.4% vs.29.6%,respectively,P=0.002).In line with these results,Karaman et al.conducted a study of 63 patients with CU younger than 18 years and 82 matched individuals with no history of urticaria or other skin diseases who served as a control group [18].Increased rates of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with CU were found compared to the control group[for the anxiety disorders: 17/63 (26.9%) compared to 3/82 (3.6%),P< 0.001;and for the depressive disorders:8/63 (12.6%) compared to 0/83 (0%),P=0.001].Interestingly,this increase was also correlated with increasing age and disease duration.

In a large cohort of adolescents in Israel,the medical records of 1,108,833 16-year-old adolescents were reviewed,and a total of 6617 (0.6%) individuals had the diagnosis of CU (study group) [19].The control group consisted of those individuals without the CU diagnosis (n=1,102,216).Psychiatric comorbidities,including depression and psychosis but not anxiety disorders,were found to be less prevalent in the study group,and the multivariate analysis further confirmed these findings [depression odds ratio (OR)=0.38,95% confidence interval (CI)=0.21-0.68,P< 0.001;psychosis OR=0.06,95% CI 0.02-0.15,P< 0.001].

Specific psychiatric comorbidities among children and adolescents with chronic urticaria

Kuo et al.aimed to provide insights into urticaria-related major depression in adolescents [20].This study used the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database.The study group included 5755 adolescents with CU and 17,265 matched non-CU control individuals.Thirty-four (0.6%)adolescents with CU and 59 (0.3%) non-CU control individuals suffered a new-onset episode of major depression.The stratified Cox proportional hazard analysis showed that the study group had a crude hazard ratio that was 1.73-timesgreater than the control group (95% CI=1.13-2.64,P< 0.05).

Comorbidity of chronic urticaria among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders

Chen et al.studied the prevalence of allergic diseases among patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder(ADHD) [21].Utilizing the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database,8201 patients with ADHD were identified and compared with 32,804 non-ADHD controls.Compared with the control group,the patients with ADHD had a greater CU prevalence than the control group (8.4%vs.6.2%,P< 0.001).Similarly,McGee et al.recruited 1037 children with ADHD at the age of three who were followed up every two years up to 15 years of age [22].An additional follow-up was performed when they were 18 years old.At the age of nine,67 out of the 815 (8.2%) children with ADHD suffered from CU.This percentage increased to 15.7% (115/735 children with ADHD) four years later.

Discussion

This systematic review investigated the psychiatric comorbidity among children and adolescents with CU.Although the included studies suggest an increased incidence of psychopathology among children and adolescents with CU as opposed to healthy age-matched individuals,the data are still remarkably scarce.Most studies are based on retrospective reviews,and no RCTs were found.The wide variability of the studies' design and the recruited participants(e.g.,demographics,ethnicity,gender),the small samples,and the different psychometric tools and diagnostic criteria used are significant limitations.It should also be noted that among the few studies that have been identified in the extant literature that show evidence of psychiatric comorbidity in CU patients,there are studies that included both pediatric and adult populations in a single group without quoting each age group separately or specifically for CU [23-31].Apart from these studies,articles that were not published in the English language were not included in this systematic review to avoid psychiatric nomenclature mistranslation and misinterpretation;these are among the limitations of the current review.

Given that mental illness in childhood and adolescence is often caused by precipitating or predisposing stressors,the hypothesis that chronic illness is a risk factor for the onset of psychopathology in youth has a solid theoretical basis [32].Several studies,including meta-analyses,epidemiological studies,and clinical sample studies,have shown that children and adolescents with chronic illnesses are more likely to develop mental health disorders [33].However,most of the studies have been cross-sectional,and relatively few have been able to use longitudinal study designs.A recent systematic review highlighted that the vast majority of research that has looked at the impact of chronic illness conditions in younger age groups had been mainly based on small,crosssectional samples of varied ages,recruited from clinically drawn samples rather than nationally representative samples that may be more generalizable [34].Furthermore,the available studies have been mainly focused on individual chronic pathological conditions [35].There has been a considerable difference in the prevalence of psychopathology among different chronic illnesses,with approximately 30% of children with neurological issues presenting with a comorbid mental illness,compared to 13% of children with asthma and 12%of children with diabetes mellitus [36].Notably,to date,there has not been any systematic review or meta-analyses within the extant literature regarding the prevalence of mental health disorders among children and adolescents with CU,despite the chronic and debilitating symptoms of this entity that are expected to have a significant impact on mental health and QoL.This could be attributed to the fact that some physicians (pediatricians,dermatologists,allergists)tend to underestimate the chronicity of the CU symptomatology in daily clinical practice [37-39],although studies report low-resolution rates,for instance,only 10% per year in Canada [38] and rates of 18.5% in the first,54% in the third and 67.7% in the fifth year after CU onset in Thailand[37].This evidence exists on top of the considerable humanistic and economic impacts of CU [40].

The consideration of CU as a chronic illness is of paramount importance for the physicians,the patients and the caregivers/parents,especially under the potential of a higher risk of comorbid psychopathology and consequently the need for a multidisciplinary approach involving prompt recognition and management of all the comorbid clinical entities.To our knowledge,this is the first systematic review in the literature that emphasizes this important aspect of CU by highlighting an increased prevalence of mental health disorders in children and adolescents with CU.

An additional burden that limits the in-depth understanding of the CU and psychiatric comorbidity is the inaccessibility to relevant health care services,lack of multidisciplinary approach due to the unawareness,or the stigma associated with the diagnosis of pediatric mental health and skin disorders [41,42].Limited mental health knowledge and broader perceptions of help-seeking,perceived social stigma and embarrassment,financial costs associated with mental health services,logistical barriers,and the availability of professional help are among the most common barriers to children and adolescents seeking and accessing professional help for mental health problems [43].On top of these,the parents (or the caregivers) sometimes avoid seeking professional help due to existing stereotypes and stigmatized attitudes.The same may apply to skin disorders,as these may negatively impact long-term psychosocial growth as well [41].

It has been well-documented that childhood and adolescence comprise a unique developmental period characterized by several physical and mental changes.However,the association between stress,mental health difficulties,and dermatologic disorders in this age group has not been adequately investigated,even though it has been shown that this age represents a time of increased susceptibility to stress[44,45].Furthermore,adolescence represents a critical time window of neural plasticity when different brain regions are still maturing and seem vulnerable to several pathological conditions,including skin disorders,potentially impacting these individuals' lives later during adulthood [46,47].

Similar to the adults,the relationship between psychiatric disorders and CU in children and adolescents remains unclear.CU pathophysiology is particularly complex,and several underlying mechanisms may explain the coexistence of atopic and central nervous system (CNS) disorders [9].Studies have shown an association between other childhood atopic disorders (e.g.,asthma,atopic eczema) and depressive or anxiety disorders [48-50].The results of our review indicate that children and adolescents with CU may also be more vulnerable to stress and to manifesting psychiatric disorders without clearly attributing the role of a cause or causality in their interrelation.According to the literature,there seems to be evidence of an increased susceptibility among disorders such as ADHD.Given the increase in CU prevalence among children with ADHD from 8.2% (67/815) at the age of nine,to 15.7% (115/735)four years after [22].This is suggestive of another type of interrelationship or a common underlying pathogenetic background.

The comorbidity of mental and atopic disorders suggests the possibility of shared or overlapping genetic,biological,or environmental risk factors contributing to the onset of these clinical entities.One area of increasing interest is the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and,in particular,its role in response to stress [51].HPA dysregulation is probably one of the mechanisms believed to contribute to the association between psychologic symptoms,stress,and immune responses of atopy [52].Psychosocial stress is correlated with anxiety and depression [53],and dysregulation of the HPA axis has been associated with the prevalence of anxiety and depression in children and adults[54].Abnormalities in the HPA axis have also been reported in children with atopy compared to healthy individuals [55,56].

Moreover,evidence shows a bidirectional relationship between the CNS and the immune system [57].The CNS modulates immune system functions by releasing neurotransmitters (such as serotonin and dopamine),neuropeptides,and cytokines [9].During an allergic or atopic response,inf almmatory cytokines may penetrate the blood-brain barrier and activate neuroimmune mechanisms involving specif ci neural circuits related to behavioral and emotional modulation [58,59].The dysregulated secretion of autoimmunity-related proinflammatory cytokines may play an essential role in the comorbid association between CU and psychiatric disorders.

The impact of stress on the morbidity associated with psychiatric and allergic disorders is also of direct clinical importance.Converging evidence suggests that stress and emotional difficulties may exacerbate childhood atopic disorders' physical symptoms and severity and may contribute to decreased QoL and increased medical care [49].Similar fnidings of an association between stress,psychologic symptoms,and exacerbation of atopic medical morbidity have also been reported in studies of other atopic disorders [52,60].

CU significantly impacts the patient's personal and social life due to its longstanding debilitating symptoms.Children with CU have suffered a substantial impairment in their QoL,similar to other chronic conditions such as epilepsy and diabetes,and considerably lower school performance compared to those with other allergic disorders[61].Multimorbidity appears to have a detrimental impact on children's QoL and physical ailment alone.This impact is widespread,affecting various dimensions of QoL [62].The extant data suggest a positive association between disease control and physical as well as psychological aspects of QoL in children and adolescents with a chronic illness[63].Pediatric CU is a long-term condition that can continue for up to ten years,and the rate of CU resolution in children is comparable to that of adults,at 10 per 100 patient-years.Thus,an adequate treatment plan in the context of a biopsychosocial approach is required over a long period for children with CU [64].

In the included studies,psychotropic medications or other psychiatric interventions were not used as a treatment option in children and adolescents with CU.However,it has been reported that antidepressants and anxiolytics could be part of the pharmacological regimen of these patients [65-67].It is noteworthy that in a study of treatment patterns among children with CU in the United States,3.8% and 1.5% of the patients used anxiolytic and antidepressant medications at baseline,respectively,and over an 18-month follow-up period,the rates of relevant medication usage increased up to 19.3% and 3%,respectively [66].

Given the increased comorbidity of CU and psychiatric disorders in adulthood [8],further research is warranted to clarify whether the emergence of psychiatric disorders in adults with CU is the result of the premorbid CU and its chronicity since childhood which in this case could serve as a potential trigger,or the psychiatric disorders pre-exist since youth and make these patients vulnerable to the onset of CU through the activation of overlapping underlying pathophysiological mechanisms that are currently unknown.With the current evidence,we cannot conclude which clinical entity develops first and substantially affects the other or whether they develop simultaneously with a shared mechanism.Additional data are required to uncover this trend and to clarify whether psychopathology is just a comorbid entity,the cause,or the consequence of CU.This will help to further explore the underlying mechanisms and identify any biological and psychosocial risk factors crucial for developing targeted prevention and treatment interventions for this special population in a patient-centered biopsychosocial approach.Meanwhile,screening for psychological difficulties or psychiatric symptoms among children and adolescents with CU should be considered in clinical practice.An interdisciplinary collaboration between allergists/dermatologists and psychiatrists is expected to substantially minimize CU burden and improve patients'QoL.

Author contributionsKGN (the first author) and KGN (the second author) contributed equally to this work.They conceptualized and designed the study,drafted the initial manuscript,reviewed,and revised the manuscript,designed the data collection instruments,collected data,carried out the initial analyses,coordinated and supervised data collection,and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content.Both authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FundingNo financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Data availabilityAll data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files,including the figures and the tables.

Declarations

Ethical approvalNot needed.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年4期

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年4期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Effect of maternal pregestational diabetes mellitus on congenital heart diseases

- Effectiveness of resilience-promoting interventions in adolescents with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Addition of respiratory exercises to conventional rehabilitation for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Effects of synbiotic supplementation on anthropometric indices and body composition in overweight or obese children and adolescents: a randomized,double-blind,placebo-controlled clinical trial

- Estimated prevalence and trends in smoking among adolescents in South Korea,2005-2021: a nationwide serial study

- Factors of heavy social media use among 13-year-old adolescents on weekdays and weekends