亲子关系、感觉加工敏感性与COMT Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的交互影响*

刘倩文 王振宏

亲子关系、感觉加工敏感性与Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的交互影响*

刘倩文 王振宏

(陕西师范大学心理学院, 陕西(高校)哲学社会科学重点研究基地-儿童青少年心理与行为健康研究中心, 西安 710062)

基于个体多重敏感性因素与环境交互的视角, 本研究探讨了亲子关系、感觉加工敏感性(Sensory Processing Sensitivity, SPS)与Val158Met多态性的交互作用对学前儿童亲社会行为的影响。研究以507名学前儿童为被试(年龄= 4.83岁,= 0.90岁), 分别采用父母报告的亲子关系量表、高敏感儿童量表、长处与困难问卷中的亲社会分问卷测量了亲子关系、儿童的SPS和亲社会行为, 采集唾液样本进行基因位点的分型。研究结果发现, 亲子冲突、SPS与Val158Met多态性的三重交互作用对儿童亲社会行为影响显著。在携带Val/Val基因型的儿童中, 高SPS儿童比低SPS儿童在低亲子冲突条件下表现更多的亲社会行为, 但在高亲子冲突条件下表现更少的亲社会行为; 在携带Met等位基因的儿童中, 亲子冲突与SPS的交互作用对儿童亲社会行为的影响不显著。研究结果表明同时具有高气质敏感性和高基因敏感性儿童的亲社会行为更容易受到亲子冲突的影响, 这为深入理解个体多重敏感性因素与家庭环境交互影响儿童发展提供了证据。

亲子关系, 感觉加工敏感性,基因, 学前儿童, 亲社会行为, 个体−环境交互

1 问题提出

儿童亲社会行为是指儿童在社会交往中自发地对他人表达关心和共情, 并做出有益于他人的行为(Eisenberg et al., 2015)。亲社会行为在儿童发展早期就已经出现, 在学前期快速发展, 并出现个体差异(Eisenberg & Miller, 1987)。亲社会行为是儿童社会化和适应性的重要表现, 良好的亲社会行为有利于儿童建立积极的社会关系, 对儿童的健康发展具有重要作用(Eisenberg et al., 2015; Flouri & Sarmadi, 2016)。

亲社会行为的形成与发展受遗传、生理、心理以及环境等因素的影响(Brett et al., 2020; Knafo et al., 2011; Zhang & Wang, 2020)。个体−环境交互作用理论认为, 儿童发展包括亲社会行为是个体因素与环境因素相互作用的结果(Knafo & Plomin, 2006)。素质−压力模型(Diathesis-Stress Model; Monroe & Simons, 1991)、差别易感性模型(Differential Susceptibility Model, Belsky & Pluess, 2009)、优势敏感性模型(Vantage Sensitivity Model, Pluess & Belsky, 2013)以及感觉加工敏感性模型(Sensory Processing Sensitivity Model, Aron et al., 2012)等儿童发展的个体−环境交互作用模型认为不同儿童对环境刺激的感知加工能力与反应性不同, 即环境敏感性不同。有的儿童环境敏感性高, 有的儿童环境敏感性低(Greven et al., 2019; Pluess, 2015)。与低敏感儿童相比, 高敏感儿童对环境刺激的反应阈限更低, 更易受到外部环境刺激的影响(Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Ellis et al., 2011; Pluess et al., 2018)。研究表明, 儿童的环境敏感性特征体现在其气质类型(如负性情绪性、感觉加工敏感性等)、神经生理特征(如迷走神经功能、皮质醇反应等)和基因多态性等多个方面(Obradović & Boyce, 2009; 王振宏, 2022)。已有大量研究分别探讨了儿童气质、神经生理特征和基因等不同敏感性与环境因素对儿童发展的交互影响, 研究结果为理解个体与环境因素交互影响儿童多样性发展结果的内在机制提供了不同证据(王振宏等, 2020)。儿童不同敏感性特征如气质、基因等不仅可能独立地与环境因素交互影响儿童的发展, 研究也提出不同敏感性因素之间会交互作用, 产生多重敏感性因素的“倍增效应”, 与环境因素共同影响儿童的发展(Obradović & Boyce, 2009)。感觉加工敏感性(Sensory Processing Sensitivity, SPS)作为一种气质敏感性, 也反映了中枢神经功能的敏感性(Acevedo, 2020)。儿茶酚胺氧位甲基转移酶(catechol-O-methyltransferase, COMT) Val158Met多态性被认为是亲社会行为相关的敏感性基因(Reuter et al., 2011)。来自脑成像的证据表明, SPS与多巴胺系统基因调控功能均与中脑奖赏区域的激活有关(Acevedo, 2020; Berke, 2018)。高SPS和等多巴胺系统敏感性基因可能会共同调节大脑相关区域的功能, 形成大脑相关区域的功能敏感性。因此, SPS与Val158Met多态性两种敏感性因素可能会交互作用, 产生“倍增效应”, 与作为家庭心理社会环境核心变量的亲子关系共同影响儿童的亲社会行为, 但已有研究对此缺乏深入探讨。

亲子关系是影响学前儿童发展最重要、最直接的人际关系(Wilson et al., 2017; Zhang, 2011)。学前期的亲子关系塑造了儿童对自我和他人的看法, 是学前儿童社会情绪调节能力发展的重要基础, 影响其其他人际关系的形成(Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998)。研究表明, 亲子关系质量越高, 儿童越容易与父母形成安全依恋关系、具有更强的共情能力, 有利于其亲社会行为的形成与发展; 而低质量的亲子关系则会增加儿童发展失调的风险以及对人际关系的消极解释, 会引起更多的社会排斥和消极情绪、更多的问题行为与更少的亲社会行为(Acar et al., 2018; Driscoll & Pianta, 2011; Eisenberg et al., 2015; Eivers et al., 2012; Pianta & Lothman, 1994)。亲子关系包括亲子亲密和亲子冲突两个维度(Pianta, 1992)。其中, 亲子亲密指父母和孩子之间温暖、信任、支持及开放的沟通和互动; 亲子冲突则代表着父母和孩子之间的消极互动和冲突体验, 如消极的情绪表达、公开的意见或行为不一致、敌对性的争执等(Driscoll & Pianta, 2011; Fang et al., 2021; Laursen & Collins, 2009)。一方面, 已有研究以亲子亲密与亲子冲突的合成分数代表亲子关系整体水平, 探讨了亲子关系质量对儿童亲社会行为发展的影响(Holland & McElwain, 2013; Zhang, 2011)。另一方面, 已有大量研究也强调亲子亲密和亲子冲突是亲子关系的两个不同方面, 亲子亲密和亲子冲突对儿童发展会产生不同的影响(Yan et al., 2019)。亲子亲密强调亲子之间的联系, 反映了亲子之间情感上的亲近以及愿意分享自己内心的想法和感受等; 而亲子冲突是指父母和孩子之间产生分歧或发生争执等, 往往伴随着愤怒或恼怒的情绪以及其它不同的应激体验(Fang et al., 2021; Laursen & Collins, 2009)。因此, 分别考察亲子亲密和亲子冲突对儿童亲社会行为的不同作用有助于更好地揭示亲子关系影响儿童亲社会行为的内在机制。

SPS被认为是个体对环境刺激的敏感性差异在气质水平上的体现(Aron & Aron, 1997)。SPS反映了个体在认知加工深度及复杂程度、情绪与生理反应性大小、对细微刺激的敏锐性和易被过度刺激性等方面的差异(Aron & Aron, 1997; Aron et al., 2012; Greven et al., 2019), 主要包括审美敏感性(AestheticSensitivity, AES)、低感觉阈限(Low Sensory Threshold, LST)和易刺激性(Ease of Excitation, EOE)三个维度。AES指具有较高的艺术和审美意识(如沉醉于美妙的音乐或风景), LST指容易觉察到外部刺激并产生不愉快的感觉(如对强光和噪音不适), EOE则代表个体易受到来自外部和内部压力的过度刺激(如对同时要做很多事情的消极反应) (Pluess et al., 2018; 曾思瑶, 王振宏, 2022)。研究表明, 与低SPS儿童相比, 具有高SPS的儿童往往对环境刺激, 特别是重要的社会情境具有更强的反应以及更深层次的加工处理, 也更容易受到外部环境的影响(Greven et al., 2019; Slagt et al., 2018)。因此, 不同SPS水平的儿童对所处环境具有不同的反应性, 从而导致环境因素会对其社会行为发展产生不同影响(Lionetti et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021)。例如, Slagt等(2018)考察了父母教养方式的变化和SPS对儿童外化行为的影响, 研究发现, 当父母消极教养减少时, 高SPS儿童的外化行为比低SPS儿童减少得更多; 当父母消极教养增多时, 高SPS儿童的外化问题也增加得更多。Li等(2022)也发现高SPS学前儿童的问题行为会更容易受到早期养育环境不可预测性的影响; 与低SPS儿童相比, 高SPS儿童在环境不可预测性较低的情况下会表现出更少的问题行为; 在环境不可预测性较高的情况下则会表现出更多的问题行为。

多巴胺系统影响着中脑边缘的奖赏通路, 能够调节个体对环境刺激的动机敏感性(motivational sensitivity), 进而影响其社会行为的形成与发展(Wise, 2004)。多巴胺与社会认知功能关系的倒“U”型曲线模型认为(Stein et al., 2006), 与高基线多巴胺水平相比, 当脑内尤其是前额叶的基线多巴胺水平较低时, 在奖赏刺激下多巴胺浓度会达到更理想的水平, 从而能够促使个体表现出更多的积极适应。已有研究表明, COMT酶能够通过使突触间隙中的儿茶酚胺失活来分解儿茶酚胺, 进而参与前额叶多巴胺的代谢(Weinshilboum, 1988; 王美萍等, 2019)。该酶由位于染色体22q11.1−11.2上的基因编码。Val158Met多态性的编号为rs4680, 是由于第158位密码子发生G (鸟嘌呤)到A (腺嘌呤)的基因突变导致密码子编码的氨基酸发生缬氨酸到蛋氨酸(valine-methionine, Val-Met)的置换形成的(Meyer et al., 2016)。Val158Met多态性的变异会影响COMT酶的活性水平, Val/Val (GG)基因型比Met/Met (AA)基因型分解多巴胺的速度快3~4倍(Lachman et al., 1996)。与Val158Met多态性Met等位基因相比,Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型编码的COMT酶活性较高, 导致脑内多巴胺基线水平较低。因此在积极的环境下, 携带Val/Val基因型个体的多巴胺功能增强, 容易将奖励及其相关环境编码为情感记忆, 从而促进积极情感并将积极行为作为获得奖励的方式(Moore & Depue, 2016; Smolka et al., 2005)。此外, 前额叶皮层晚熟理论认为, 当边缘系统与前额叶连通性较低时, 儿童对环境有着更强的反应性(Andersen & Teicher, 2008)。而Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型与前额叶和边缘结构回路的连通性降低以及奖赏加工减少相关(Drabant et al., 2006)。因此, 与Met等位基因携带者相比, 携带Val/Val基因型的个体可能也会对消极环境更敏感, 容易产生更多的负面情绪和更少的积极行为。多项以亚洲人群为样本的基因−环境交互研究也发现, 与携带其他基因型的个体相比, 携带Val/Val基因型个体的抑郁水平、自杀意念、注意控制能力等会更容易受到环境的影响, 从而表现出不同的发展结果(Kwon et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021; 曹衍淼等, 2017; 王美萍等, 2019)。综上所述,Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型可能是一个对环境刺激高敏感的基因型, 携带该基因型儿童的亲社会行为会更容易受到外部环境的影响。

SPS是一种气质敏感性指标, 高SPS儿童更容易受到家庭环境的影响(Slagt et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022)。与气质敏感性类似, Belsky等(2009)提出特定的基因或遗传变异同样能够调节环境对个体适应的影响, 其中携带敏感基因型的个体会更容易受到环境的影响, 其行为发展也具有更高的可塑性。已有实证研究表明,Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型是个体亲社会行为的敏感基因型(Ru et al., 2017)。而Obradović和Boyce (2009)提出, 基因、神经生理特征、气质等不同类型的敏感性因素之间可能会交互作用, 产生多重敏感性因素的“倍增效应”, 从而与环境因素交互影响儿童的发展。由此可以推断, 与其他儿童相比, 携带Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型的高SPS儿童(即具有双重敏感性因素儿童)的亲社会行为可能更容易受到外部环境的影响。或者说, SPS、Val158Met多态性与环境因素是否交互影响儿童亲社会行为发展也可能会受到二者彼此的调节。来自脑成像的证据表明SPS与大脑奖赏处理脑区的激活相关; 与低SPS个体相比, 高SPS个体在面对积极刺激时会表现出更强的奖赏反应, 中脑腹背盖区(Ventral tegmental area, VTA)会表现出更高的活性; 而在面对消极刺激时, 其奖赏相关脑区的活性会显著降低(Acevedo et al., 2014; Acevedo et al., 2018; Acevedo, 2020)。同时, 多巴胺系统基因包括基因也会通过影响中脑边缘的奖赏通路来发挥作用(Berke, 2018; Wise, 2004)。因此, 在面对环境刺激信息时, 高SPS和多巴胺系统的敏感性基因型可能会共同调节或影响大脑相关区域的功能, 形成大脑相关区域神经功能的敏感性, 发挥多重敏感性的“倍增效应”, 从而影响个体的社会行为。亲子关系实质上表征着家庭心理社会环境的刺激信息。具有不同SPS与Val158Met多态性基因型的儿童, 其亲社会行为发展受亲子关系影响的程度可能会不同, 同时具有高SPS与Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型儿童的亲社会行为可能受亲子关系质量等环境因素的影响更大。如前所述, 亲子亲密和亲子冲突虽然都是亲子关系的核心维度, 但二者有所不同。亲子亲密表征着亲子之间的情感联结, 而冲突更多地与亲子之间的对抗并与广泛的应激反应相联系。因此, SPS、Val158Met多态性与亲子亲密、亲子冲突对儿童亲社会行为的交互影响也可能不同。

本研究基于个体多重敏感性因素与环境交互作用的视角, 考察了SPS、Val158Met多态性与亲子关系质量对学前儿童亲社会行为的交互影响。基于前述研究依据, 我们预期, 与携带Met等位基因的儿童相比, 携带Val/Val基因型(高敏感性基因型)的高SPS (高气质敏感性)儿童的亲社会行为更易受到亲子关系质量的影响, 而且携带Val/Val基因型的高SPS儿童对亲子亲密与亲子冲突可能会表现出不同的反应性, 从而表现出不同的亲社会行为。

2 方法

2.1 被试

来自西安市两所幼儿园共507名学前儿童(= 4.83岁,= 0.90岁, 236名女孩)及其父母参与了研究。我们采用父母受教育程度和家庭月均收入水平标准化后的总分作为家庭社会经济地位的指标(Cohen et al., 2006), 其中父母受教育程度为7点计分(“没有上过小学”、“小学”、“初中”、“高中”、“大专或本科”、“硕士研究生”和“博士研究生”), 家庭月均收入水平为5点计分(“低于3000元”、“3000~7000元”、“7000~10000元”、“10000~20000元”和“高于20000元”)。在本研究中, 儿童母亲受教育程度硕士及以上占51.5%, 大专(本科)占46.5%, 高中及以下占2%; 儿童父亲受教育程度硕士及以上占53.3%, 大专(本科)占44.5%, 高中及以下占2.2%; 儿童的家庭月均收入20000元及以上占39.6%, 10000~20000元占42.4%, 10000元以下占18%。此外, 已有研究表明, 基因与环境的交互作用达到显著水平(α = 0.05)时效果量一般为0.01 (Starr et al., 2014)。基于此, 研究采用G*Power 3.1.9.7软件进行分析, 显示要达到80%以上的统计功效, 约需要787名被试, 研究被试量基本满足要求。

2.2 工具

2.2.1 亲子关系

采用Pianta (1992)编制、张晓等(2008)修订的亲子关系量表(the Parent-Child Relationship Scale, PCRS)测量儿童和父母的亲子关系质量。该量表包括3个维度(亲密性、冲突性与依赖性), 共26道题目, 采用5点计分(1表示完全不符合, 5表示完全符合)。由于以往研究表明, 依赖性分量表的信效度并不理想(张晓等, 2008), 本研究仅采用亲密分量表和冲突分量表对亲子关系进行评估。在本研究中, 亲密分量表的Cronbach’s α系数为0.63, 冲突分量表的Cronbach’s α系数为0.80。

2.2.2 感觉加工敏感性

采用Slagt等(2018)编制、曾思瑶和王振宏(2022)修订的中文版高敏感儿童量表(the Chinese Version of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale, HSC-C)测量儿童的SPS。该量表包括3个维度(易刺激性、审美敏感性与低感觉阈限), 共12道题目, 采用7点计分(1 代表完全不同意, 7代表完全同意), 得分越高代表SPS水平越高。在本研究中, 高敏感儿童量表的Cronbach’s ɑ系数为0.65, 其中易刺激性、审美敏感性与低感觉阈限分量表的Cronbach’s α系数分别为0.52、0.66和0.58。

2.2.3 亲社会行为

采用Goodman (1999)编制、高欣等(2013)修订的长处与困难问卷(the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SDQ)中的亲社会分问卷来测量儿童的亲社会行为。该分问卷包括5道题目, 3点计分(0 代表不符合, 2代表完全符合), 得分越高代表亲社会水平越高。在本研究, 亲社会分问卷的Cronbach’s α系数为0.71。

2.2.4 施测程序

本研究经过所在学校伦理委员会的审核批准, 在被试父母和幼儿园签署知情同意书之后进行研究测评。首先, 幼儿园各班的班主任老师将相关问卷发放给儿童, 儿童将问卷带回家后, 由其主要的监护人进行填写。随后, 儿童将填写后的问卷带回班里交给班主任老师采用Harman单因子检验方法对所有监护人报告的问卷题目进行共同方法偏差检验 (Podsakoff et al., 2003)。结果发现, 共有11个因子的特征值大于1, 最大因子解释的变异量为16.02%, 小于40%的临界值, 表明数据不存在共同方法偏差。。最后, 在班级内经由严格培训的研究生采集儿童的唾液样本。研究使用厦门致善生物科技股份有限公司生产的唾液DNA样本采集管(型号:SAL-2000L)进行唾液采集。采集前半小时内儿童被要求禁止喝水和进食。在采集过程中, 儿童需向采集漏斗中轻轻吐入唾液, 直至液体唾液(非气泡)达到刻度线高度(2 ml)。随后主试旋下采集漏斗, 用管盖将采集管拧紧, 并上下颠倒采集管使唾液与原采集管中的唾液保存液充分混匀。采集的样本要求无杂物、无痰液, 于室温下保存。最后由专业的生物分析公司进行DNA样本的提纯和分型。

2.3 基因检测

基因分型由北京康普森生物技术有限公司采用Sequenom质谱法完成。Val158Met多态性的引物为F: ACGTTGGATGATCACCATCGAGATCAACCC, R: ACGTTGGATGTTTTCCAGGTCTGACAACGG。Val158Met多态性的基因型分布符合Hardy-Weinberg遗传平衡(Met/Met = 37人, Met/Val = 187人, Val/Val = 283; χ2= 0.34,= 2> 0.05)。根据已有研究以及本研究的研究假设, 我们将Val158Met多态性Met/Met基因型和Met/Val基因型合并为Met等位基因组(Met+ = 224, Val/Val = 283)进行编码及分析(Met+ = 0, Val/Val = 1) (Zhang et al., 2021; 曹丛等, 2017)。

2.4 数据处理与分析

运用SPSS 24.0、Mplus 8.3和R统计软件进行数据处理与分析。已有研究表明, 学前儿童随着年龄的增长其亲社会水平也会呈上升趋势(Hoffmann, 2007), 同时家庭社会经济地位作为家庭客观环境的核心变量也影响其亲社会行为(Cowell et al., 2017; 张文新等, 2021)。此外, 多巴胺系统基因在与环境交互影响儿童社会行为上可能存在性别差异(O'Brien et al., 2013; 王美萍, 张文新, 2010)。因此, 研究将性别、年龄和家庭社会经济地位作为控制变量, 通过分层回归分析来探究亲子亲密/亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的主效应和交互效应。回归分析前, 对连续变量均进行了标准化处理以避免多重共线性。此外, 在进行回归分析时采用Bootstrap法进行10000次随机抽样对数据结果进行验证。由于亲子亲密和亲子冲突之间存在显著负相关, 研究在分别考察亲密/冲突的作用时, 也在相应的模型中控制

了亲子关系的另一个维度。如果亲密/冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的交互效应显著, 则对显著的交互项进一步进行简单斜率分析, 并采用显著性区域检验和再参数化回归分析来判断交互作用模式符合何种理论模型(Roisman et al., 2012; Widaman et al., 2012)。

3 结果

3.1 描述性统计和相关分析

相关分析表明, 亲子亲密、SPS与亲社会行间呈显著正相关, 亲子冲突与学前儿童的亲社会行为显著负相关(< 0.01)。亲子冲突与SPS,Val158Met多态性与亲子亲密、亲子冲突、亲社会行为间的相关均不显著。各变量的平均值、标准差以及变量间的相关系数见表1。

3.2 亲子关系、SPS和COMT Val158Met多态性对亲社会行为的交互效应分析

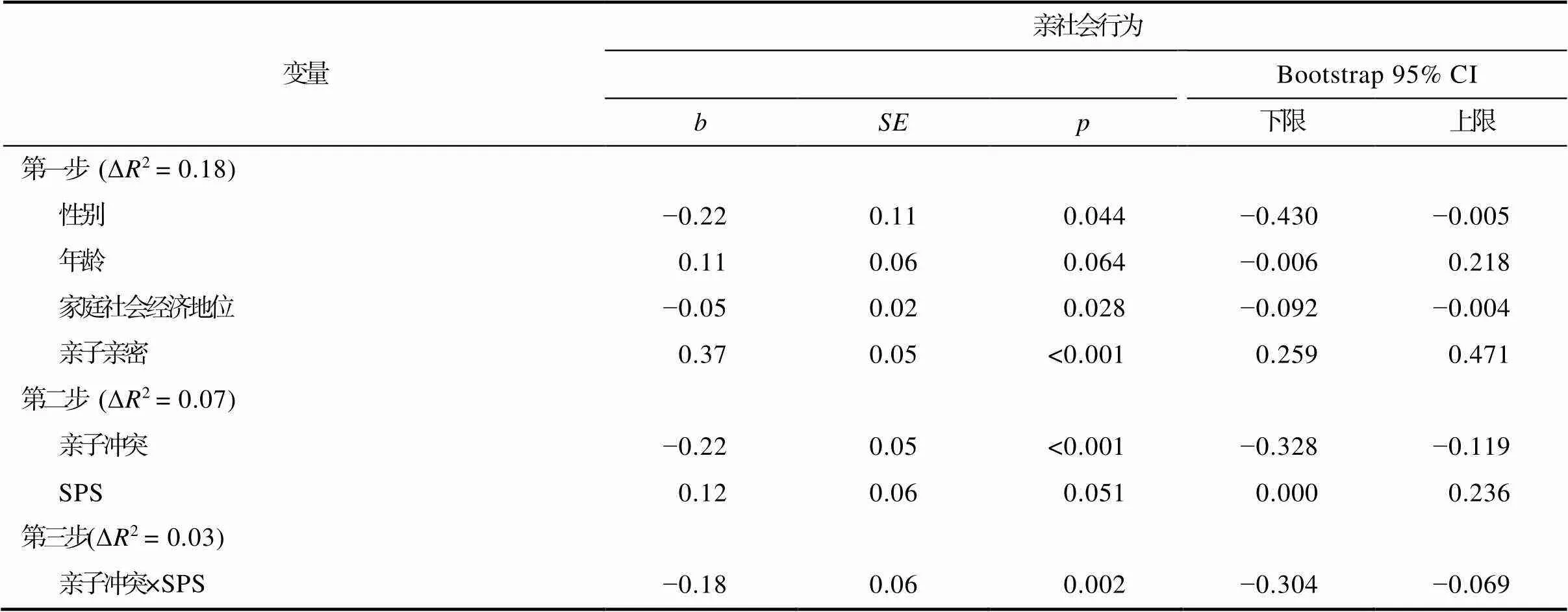

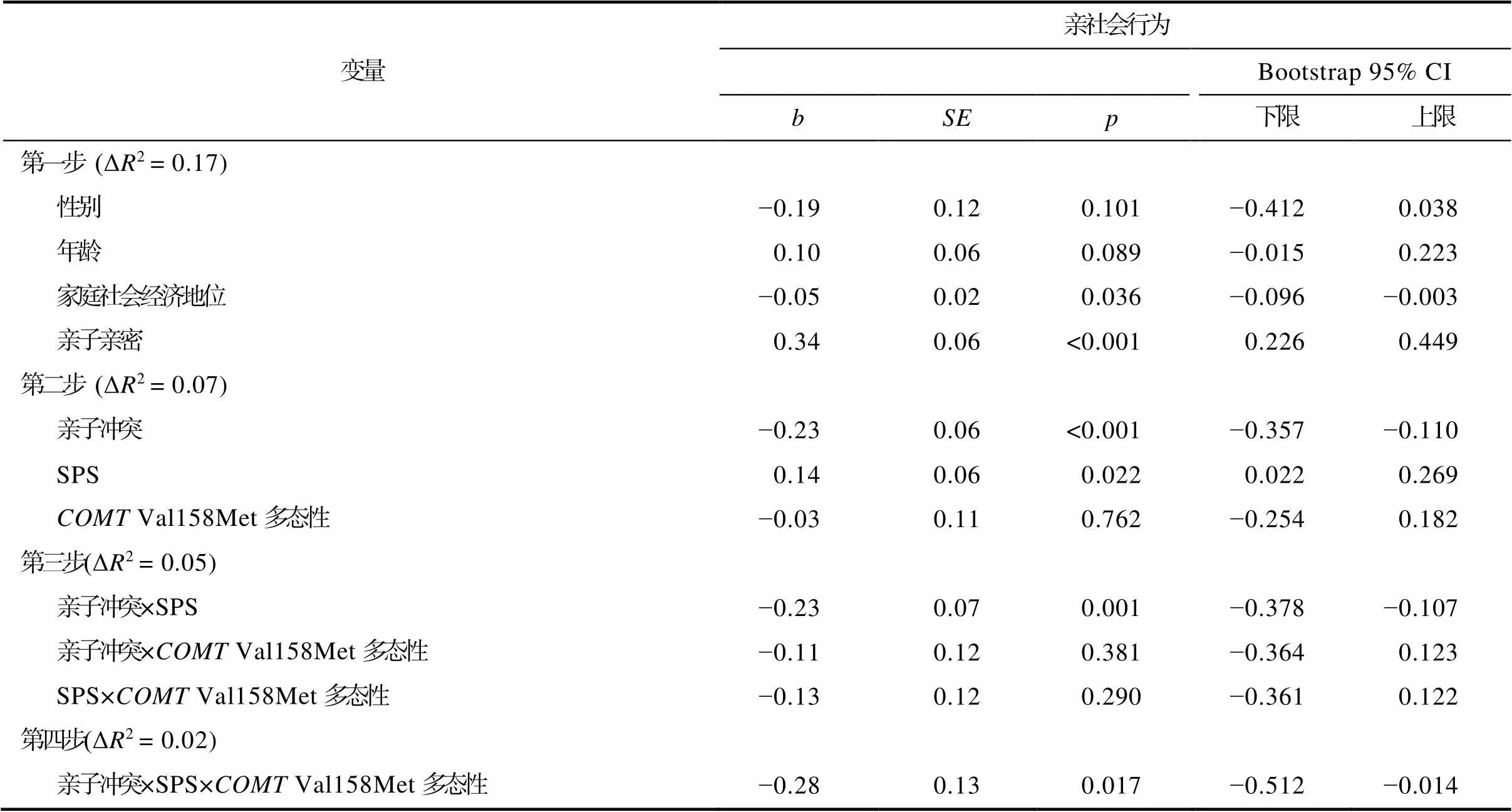

研究采用分层回归分析方法分别考察亲子亲密/亲子冲突与SPS、Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的主效应和交互效应。数据分析显示(见表2~3), 亲子亲密、亲子冲突和SPS对学前儿童亲社会行为的主效应显著(s < 0.01); 亲子亲密/冲突×SPS、亲子亲密/冲突×Val158Met多态性以及SPS×Val158Met多态性对亲社会行为的效应均不显著; 亲子亲密、SPS和Val158Met多态性对亲社会行为的三重交互效应不显著, 而亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性能够三重交互作用于学前儿童的亲社会行为(0.003, 95% CI [−0.399, −0.076])。进一步的交互作用分析显示(见表4~5), 在携带Val/Val基因型的学前儿童中, 亲子冲突与SPS对其亲社会行为的交互作用显著(0.002, 95% CI [−0.304, −0.069]); 在携带Met等位基因的学前儿童中, 亲子冲突与SPS对其亲社会行为的交互作用不显著。随后, 研究通过显著性区域检验和再参数化回归分析, 考察在携带Val/Val基因型的学前儿童中, 亲子冲突和SPS对亲社会行为的交互作用模式(Roisman et al., 2012; Widaman et al., 2012)。显著性区域检验考察了结果变量(亲社会行为)在调节变量(SPS)的不同水平上(± 1)存在显著差异时, 环境变量(亲子冲突)的取值区间([−1.893, 3.089])。使用Mplus 8.3软件进行显著性区域检验结果发现, 在高SPS儿童中, 亲子冲突对亲社会行为的主效应显著(= −0.42,< 0.001, 95% CI [−0.558, −0.273]); 而在低SPS儿童中, 亲子冲突对亲社会行为的主效应不显著(= −0.05,= 0.460, 95% CI [−0.186, 0.084])。具体而言, 在亲子冲突较少的条件下(亲子冲突得分低于X = 0.01), 高SPS儿童的亲社会行为水平显著高于低SPS儿童; 在亲子冲突较多的条件下(亲子冲突得分高于X = 1.68), 高SPS儿童的亲社会行为水平显著低于低SPS儿童, 该交互作用模式符合“差别易感性”模型(见图1)。此外, 研究使用R统计软件进行再参数化回归分析[模型亲社会行为=B+B× 性别 +B× 年龄 +B× SES +B× 亲子亲密+ B× (−) +B× (−) ×X+] (Widaman et al., 2012)进一步验证了交互效应的作用模式。结果显示, 交叉点(= −/)的点估计值及其95%置信区间(= 0.65, 95% CI [0.002, 1.719])在亲子冲突的取值范围([−1.893, 3.089])内, 即亲子冲突与SPS对携带Val/Val基因型学前儿童亲社会行为的交互作用模式符合“差别易感性”模型。

注:*< 0.05;**< 0.01;***< 0.001。

表2 亲子亲密、SPS和COMT Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的影响

表3 亲子冲突、SPS和COMT Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的影响

表4 亲子冲突和SPS在携带Val/Val基因儿童亲社会行为中的交互作用

表5 亲子冲突和SPS在携带Met等位基因儿童亲社会行为中的交互作用

3.3 内部验证

采用内部一致性分析方法, 把总样本随机分为两个子样本来检验亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为交互效应的稳定性和可靠性(子样本1:= 245; 子样本2:= 262)。两个子样本在基因型(χ2(2) = 0.78,= 0.677)、性别(χ2(1) =1.58,= 0.214)、年龄(= 0.37,= 0.709)、家庭社会经济地位(= −0.14,= 0.886)、亲子冲突(=0.77,= 0.443)、SPS (= 0.38,= 0.707)和亲社会行为(= 0.14,= 0.887的得分上均不存在显著差异。内部一致性分析的结果显示, 亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性的三重交互作用在子样本1 (见表6)和子样本2 (见表7)中均显著, 子样本的结果与总样本结果一致。

4 讨论

本研究探讨了亲子关系包括亲子亲密与亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的交互影响。研究结果发现, 亲子亲密、SPS与学前儿童亲社会行为间呈显著正相关, 亲子冲突与亲社会行为显著负相关。亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的三重交互作用显著, 即在携带Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型的儿童中, 与低SPS儿童相比, 高SPS儿童在低亲子冲突条件下会表现出更多的亲社会行为, 在高亲子冲突条件下则表现出更少的亲社会行为。

与以往研究结果一致, 本研究发现亲子亲密与学前儿童亲社会行为显著正相关, 亲子冲突与亲社会行为显著负相关。已有研究表明, 亲子关系作为一种核心的家庭心理社会环境因素, 是儿童认知、情感和行为发展最重要的预测因素之一(Eivers et al., 2012; Pianta & Lothman, 1994)。长期的、激烈的亲子冲突会对亲社会行为产生不利影响; 相反, 高水平的亲子亲密代表着积极的家庭环境, 学前儿童在良好的亲子互动中会发展出更多的亲社会行为以及更好的社会适应(Driscoll & Pianta, 2011; Eisenberg et al., 2015)。本研究进一步支持了这一结论。同时, 研究发现SPS与学前儿童的亲社会行为呈显著正相关, 这与已有研究结果有所不同。多项实证研究表明, SPS往往与儿童的不适应行为如外化问题、负性情绪性等显著正相关(Lionetti et al., 2022; Slagt et al., 2018), 而与适应性行为不相关或者负相关(Iimura & Kibe, 2020; Lionetti et al., 2019; Slagt et al., 2018)。也有研究发现SPS与开放性、积极情感等积极特质呈显著正相关(Pluess et al., 2018; 曾思瑶, 王振宏, 2022)。依据SPS理论, 高SPS的儿童对环境更加敏感, 更容易觉察到他人的情绪感受, 具有较高的共情关怀等, 因此, 与低SPS儿童相比, 高SPS儿童可能会表现出更高的亲社会行为(Acevedo et al., 2018; Aron et al., 2012)。本研究在我国学前儿童中发现SPS与亲社会行为呈显著正相关, 这也表明SPS与儿童亲社会行为发展的关系可能存在文化上的差异。在中国儿童被试群体中, SPS可能与亲社会行为正相关, 高SPS儿童倾向于表现出更多的亲社会行为, 这一研究结果也得到初步研究证据的支持(李喜乐, 2021)。

图1 亲子冲突与SPS对携带Val/Val基因型儿童亲社会行为的交互作用图

表6 亲子冲突、SPS和COMT Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的影响(子样本1)

表7 亲子冲突、SPS和COMT Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的影响(子样本2)

研究结果发现,Val158Met多态性与亲密/冲突、SPS与亲密/冲突的二重交互作用均不显著, 亲子亲密、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的三重交互作用也不显著, 但亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为具有显著的三重交互作用。具体而言, 在携带Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型的儿童中, 与低SPS儿童相比, 高SPS儿童在低亲子冲突水平下会表现出更多的亲社会行为, 在高亲子冲突条件下表现出更少的亲社会行为。而在携带Val158Met多态性Met等位基因的儿童中, 亲子冲突与SPS的交互效应不显著。与Val158Met多态性Met等位基因相比, Val/Val基因型代表更高的COMT酶活性和更低的基线多巴胺水平。在低冲突的亲子互动中, 携带Val/Val基因型的高SPS儿童的多巴胺系统会被频繁激活, 编码积极的奖励和促进趋近行为, 个体脑内多巴胺浓度会达到更理想的水平, 有利于其亲社会行为的发展(Moore & Depue, 2016; Reuter et al., 2011; Ru et al., 2017; Stein et al., 2006)。因此, 与Met等位基因携带者相比, 携带Val/Val基因型的高SPS儿童更有可能从低亲子冲突中获益, 发展得“更好”, 表现出较多的亲社会行为。而在高冲突亲子互动中, 由于学前儿童前额叶皮层尚未发育成熟, 前额叶与边缘系统之间联通性较低, 儿童对消极刺激有较强的反应性(Andersen & Teicher, 2008)。与此同时, 与Val158Met多态性Met等位基因携带者相比, 携带Val/Val基因型儿童对应激刺激也更敏感(Hygen et al., 2014; Hygen et al., 2015; Poletti et al., 2013)。因此, 携带Val/Val基因型的高SPS儿童在高亲子冲突条件下其亲社会行为会显著降低。以上结果支持了差别易感性模型的观点(Belsky & Pluess, 2009), 也支持了在亚洲人群样本的Val158Met多态性中, 与Met等位基因相比, Val/Val基因型更多是一个环境敏感性基因型(Kwon et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021;曹衍淼等, 2017; 王美萍等, 2019), 尽管也有研究显示, 对于攻击行为的形成, Met等位基因可能是环境敏感性基因型(Zhang et al., 2016)。

此外, 上述研究结果也表明具有双重敏感性因素即高气质敏感性和高基因敏感性的儿童可能会更容易受到家庭应激环境的影响, 研究结果支持了多重敏感性因素(高SPS、Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型)对儿童亲社会行为影响的“倍增效应” (Obradović & Boyce, 2009)。也就是说, 与其他儿童相比, 具有单一的敏感因素如高SPS或者携带Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型的儿童在不同心理应激环境因素影响下, 其亲社会行为不会有显著的变化; 但同时具有高SPS及携带Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型的儿童在不同心理应激环境因素的影响下, 其亲社会行为可能会产生实质性的改变。来自脑成像的证据也表明, 高SPS和多巴胺系统敏感性基因功能均与中脑奖赏区域的激活有关(Acevedo, 2020; Berke, 2018)。因此, 在面对环境刺激信息时, 与其他儿童相比, 同时具有双重敏感性因素儿童的大脑相关区域活性可能会发生更显著的变化, 进而作用于其亲社会行为发展。

本研究没有发现亲子亲密、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的显著三重交互作用。这可能是由于Val158Met多态性不同基因型代表的不同水平的COMT酶活性会影响儿童的应激反应和自我调节机制, 从而影响其社会行为的形成与发展(Poletti et al., 2013)。如前所述, 与Val158Met多态性的Met等位基因相比, Val/Val基因型可能对于应激刺激更加敏感(Hygen et al., 2014; Hygen et al., 2015; Poletti et al., 2013)。亲子关系中, 亲子冲突表征了亲子之间的对抗与对立, 反映了亲子互动的应激过程和应激反应,构成了儿童重要的心理应激源。因此, 携带Val158Met多态性的Val/Val基因型的高SPS儿童可能更容易受到应激环境的影响, 在应激水平较低(低冲突)的条件下发展形成更多的亲社会行为, 在应激水平较高(高冲突)的条件下亲社会行为受损, 表现出更少的亲社会行为。亲子亲密则代表着亲子之间相互影响的程度和亲密感受, 以及亲子之间自愿的交流和接触(Yan et al., 2019), 亲子亲密的高低与应激反应没有直接的联系。因此, 在相同的亲子亲密水平下, 携带Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型的高SPS儿童与其他儿童的亲社会行为可能不会表现出显著差异。

综上所述, 本研究首次发现了亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性对学前儿童亲社会行为的交互效应, 为多重敏感性因素与环境交互影响儿童亲社会行为发展提供了有意义的启示。但研究也存在一些局限需要进一步考虑:(1)研究仅选取了基因的一个位点来探究亲子亲密/亲子冲突、SPS和基因对儿童亲社会行为发展的交互影响。就多巴胺功能而言, 个体携带的敏感性等位基因(低活性多巴胺等位基因)数量越多, 其共情能力和亲社会倾向可能更强; 且相比单个基因位点与环境的交互作用相比, 多基因累加得分的解释率也会更高(Sáez et al., 2015; 曹衍淼, 张文新, 2019)。未来研究应结合多巴胺系统其他的基因位点如rs6267等计算候选多基因累加得分来探讨儿童亲社会行为发展的基因基础及其与SPS等其他敏感因素和环境因素对儿童亲社会行为发展的交互影响。(2) SPS作为一种相对稳定的特质, 会受到遗传因素和早期环境的共同影响(Acevedo, 2020; Assary et al., 2020)。已有研究发现, 多巴胺系统基因()、血清素系统基因()与脑源性神经营养因子基因()都可能参与调节个体的SPS (Acevedo, 2020; Drury et al., 2010; Drury et al., 2012; Lester et al., 2012; Licht et al., 2011)。因此, SPS除能够作为一种气质敏感性与其他类型的环境敏感性因素交互作用, 与外部环境共同作用于儿童的社会适应外, 基于“基因×环境—内表型—行为”的理论模型(Nava- Gonzalez et al., 2017; 张文新等, 2021), SPS同样可能作为内表型在基因×环境影响儿童社会行为发展之间起中介作用。SPS的遗传与环境交互研究及其在儿童行为发展中的作用机制在未来研究中应予以进一步关注。(3)本研究是横断研究, 未来应采取纵向研究设计来探讨家庭环境和多重敏感性因素对儿童亲社会行为发展水平及变化轨迹的影响。(4)本研究中被试量相对偏少, 且被试的家庭社会经济地位总体偏高, 未来研究应在更大的具有不同社会经济地位的学前儿童样本中进一步检验研究结果的稳定性。

5 结论

(1)亲子亲密、SPS与学前儿童亲社会行为间呈显著正相关, 亲子冲突与亲社会行为间呈显著负相关。

(2)亲子冲突、SPS和Val158Met多态性三重交互影响学前儿童的亲社会行为。在携带Val158Met多态性Val/Val基因型的儿童中, 与低SPS儿童相比, 高SPS儿童在低亲子冲突条件下会表现出更多的亲社会行为, 在高亲子冲突条件下表现出更少的亲社会行为, 表明Val/Val基因型是潜在的环境敏感性基因型。

Acar, I. H., Evans, M. Y. Q., Rudasill, K. M., & Yildiz, S. (2018). The contributions of relationships with parents and teachers to Turkish children’s antisocial behavior.(7)877−897.

Acevedo, B. P. (2020).. Academic Press.

Acevedo, B. P., Aron, E. N., Aron, A., Sangster, M. D., Collins, N., & Brown, L. L. (2014). The highly sensitive brain: An fMRI study of sensory processing sensitivity and response to others’ emotions.(4), 580−594.

Acevedo, B., Aron, E., Pospos, S., & Jessen, D. (2018). The functional highly sensitive brain: A review of the brain circuits underlying sensory processing sensitivity and seemingly related disorders.(1744), 20170161.

Andersen, S. L., & Teicher, M. H. (2008). Stress, sensitive periods and maturational events in adolescent depression.(4), 183−191.

Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (1997). Sensory processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality.(2), 345−368.

Aron, E. N., Aron, A., & Jagiellowicz, J. (2012). Sensory processing sensitivity: A review in the light of the evolution of biological responsivity.(3), 262−282.

Assary, E., Zavos, H. M. S., Krapohl, E., Keers, R., & Pluess, M. (2020). Genetic architecture of environmental sensitivity reflects multiple heritable components: A twin study with adolescents.(9), 4896−4904.

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences.(6), 885−908.

Belsky, J., Jonassaint, C., Pluess, M., Stanton, M., Brummett, B., & Williams, R. (2009). Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes?(8), 746−754.

Berke, J. D. (2018). What does dopamine mean?(6), 787−793.

Brett, B. E., Stern, J. A., Gross, J. T., & Cassidy, J. (2020). Maternal depressive symptoms and preschoolers’ helping, sharing, and comforting: The moderating role of child attachment.(5), 623−636.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes.(Vol. 1, pp. 563−634)Wiley.

Cao, C., Wang, M., Cao, Y., Ji, L., & Zhang, W. (2017). The interactive effects of monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene and peer victimization on depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: The moderating role of catechol-O- methyltransferase (COMT) gene.(2), 206−218.

[曹丛, 王美萍, 曹衍淼, 纪林芹, 张文新. (2017). MAOA基因T941G多态性与同伴侵害对男青少年早期抑郁的交互作用: COMT基因Val158Met多态性的调节效应.(2), 206−218.]

Cao, Y., Lin, X., Ji, L., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, W. (2017). The interaction between Val158Met polymorphism in the COMT gene and peer relationship on adolescents’ depression.(2), 216−227.

[曹衍淼, 林小楠, 纪林芹, 张粤萍, 张文新. (2017). COMT基因Val158Met多态性与同伴关系对青少年抑郁的影响.(2), 216−227. ]

Cao, Y., & Zhang, W. (2019). The influence of dopaminergic genetic variants and maternal parenting on adolescent depressive symptoms: A multilocus genetic study.(10), 1102−1115.

[曹衍淼, 张文新. (2019). 多巴胺系统基因与母亲教养行为对青少年抑郁的影响:一项多基因研究.,(10), 1102−1115.]

Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., & Baum, A. (2006). Socioeconomic status is associated with stress hormones.(3), 414−420.

Cowell, J. M., Lee, K., Malcolm-Smith, S., Selcuk, B., Zhou, X., & Decety, J. (2017). The development of generosity and moral cognition across five cultures(4), e12403.

Drabant, E. M., Hariri, A. R., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Munoz, K. E., Mattay, V S., Kolachana, B. S., …Weinberger, D. R. (2006). Catechol-O-methyltransferase ValI58Met genotype and neural mechanisms related to affective arousal and regulation.(12), 1396− 1406.

Driscoll, K., & Pianta, R. C. (2011). Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of conflict and closeness in parent-child relationships during early childhood.1−24.

Drury, S. S., Gleason, M. M., Theall, K. P., Smyke, A. T., Nelson, C. A., Fox, N. A., & Zeanah, C. H. (2012). Genetic sensitivity to the caregiving context: The influence of 5HTTLPR and BDNF Val66Met on indiscriminate social behavior.,(5), 728−735.

Drury, S. S., Theall, K. P., Smyke, A. T., Keats, B. J. B., Egger, H. L., Nelson, C. A., … Zeanah, C. H. (2010). Modification of depression by COMT Val158Met polymorphism in children exposed to early severe psychosocial deprivation.,(6), 387−395.

Ellis, B. J., Boyce, W. T., Belsky, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2011). Differential susceptibility to the environment: An evolutionary- neurodevelopmental theory.(1), 7−28.

Eisenberg, N., & Miller, P. A. (1987). The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors.(1), 91−119.

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2015). Prosocial development. In M. E. Lamb & R. M. Lerner (Eds.),(Vol. 3, pp. 610−656). Wiley

Eivers, A. R., Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., & Borge, A. (2012). Concurrent and longitudinal links between children’s and their friends’ antisocial and prosocial behavior in preschool.(1), 137−146.

Fang, S., Galambos, N. L., & Johnson, M. D. (2021). Parent-child contact, closeness, and conflict across the transition to adulthood.,(4), 1176−1193.

Flouri, E., & Sarmadi, Z. (2016). Prosocial behavior and childhood trajectories of internalizing and externalizing problems: The role of neighborhood and school contexts.(2), 253−258.

Gao, X., Shi, W., Zhai, Y., He, L., & Shi, X. (2013). Results of the parent-rated Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in 22, 108 primary school students from 8 provinces of China.(6), 364−374.

[高欣, 石文惠, 翟屹, 何柳, 施小明. (2013). 长处与困难问卷(父母版)在中国8个省份22, 108名小学生中的调查结果(英文).(6), 364−374.]

Goodman, R. (1999). The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden.,(5), 791−799.

Greven, C. U., Lionetti, F., Booth, C., Aron, E. N., Fox, E., Schendan, H. E., ... Homberg, J. (2019). Sensory processing sensitivity in the context of environmental sensitivity: A critical review and development of research agenda., 287−305.

Hoffman, M. L. (2007). The origins of empathic morality in toddlerhood. In C. A. Brownell & C. B. Kopp (Eds.),(pp. 132−145). The Guilford Press.

Holland, A. S., & McElwain, N. L. (2013). Maternal and paternal perceptions of coparenting as a link between marital quality and the parent-toddler relationship.(1), 117−126.

Hygen, B. W., Belsky, J., Stenseng, F., Lydersen, S., Guzey, I. C., & Wichstrøm, L. (2015). Child exposure to serious life events, COMT, and aggression: Testing differential susceptibility theory.(8), 1098−1104.

Hygen, B. W., Guzey, I. C., Belsky, J., Berg-Nielsen, T. S., & Wichstrøm, L. (2014). Catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met genotype moderates the effect of disorganized attachment on social development in young children.(4), 947−961.

Iimura, S., & Kibe, C. (2020). Highly sensitive adolescent benefits in positive school transitions: Evidence for vantage sensitivity in Japanese high-schoolers.(8), 1565−1581.

Knafo, A., Israel, S., & Ebstein, R. P. (2011). Heritability of children’s prosocial behavior and differential susceptibility to parenting by variation in the dopamine receptor D4 gene.(1), 53−67.

Knafo, A., & Plomin, R. (2006). Prosocial behavior from early to middle childhood: Genetic and environmental influences on stability and change.(5), 771−786.

Kwon, A., Min, D., Kim, Y., Jin, M. J., & Lee, S. H. (2019). Interaction between catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism and childhood trauma in suicidal ideation of patients with post−traumatic stress disorder.(8), e01733.

Lachman, H. M., Papolos, D. F., Saito, T., Yu, Y. M., Szumlanski, C. L., & Weinshilboum, R. M. (1996). Human catechol-O-methyltransferase pharmacogenetics: Description of a functional polymorphism and its potential application to neuropsychiatric disorders.(3), 243−250.

Laursen, B., & Collins, W. A. (2009). Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In R. M. Lerner& L. Steinberg (Eds.),(Vol. 2, pp. 3−42). Wiley.

Lester, K. J., Hudson, J. L., Tropeano, M., Creswell, C., Collier, D. A., Farmer, A., … Eley, T. C. (2012). Neurotrophic gene polymorphisms and response to psychological therapy.,, e108.

Li, Z., Sturge-Apple, M. L., & Davies, P. T. (2021). Family context in association with the development of child sensory processing sensitivity.(12), 2165−2178.

Li, Z., Sturge-Apple, M. L., Jones-Gordils, H. R., & Davies, P. T. (2022). Sensory processing sensitivity behavior moderates the association between environmental harshness, unpredictability, and child socioemotional functioning.(2), 675−688.

Licht, C. L., Mortensen, E. L., & Knudsen, G. M. (2011). Association between sensory processing sensitivity and the serotonin transporter polymorphism 5-HTTLPR short/short genotype.,(9), 152S−153S.

Li, X. (2021).(Unpublished master’s thesis). Southwest University, China.

[李喜乐. (2021).(硕士学位论文). 西南大学.]

Lionetti, F., Aron, E. N., Aron, A., Klein, D. N., & Pluess, M. (2019). Observer-rated environmental sensitivity moderates children’s response to parenting quality in early childhood.(11), 2389−2402.

Lionetti, F., Spinelli, M., Moscardino, U., Ponzetti, S., Garito, M., Dellagiulia, A., ... Pluess, M. (2022). The interplay between parenting and environmental sensitivity in the prediction of children’s externalizing and internalizing behaviors during COVID-19..

Meyer, B. M., Huemer, J., Rabl, U., Boubela, R. N., Kalcher, K., Berger, A., ... Pezawas, L. (2016). Oppositional COMT Val158Met effects on resting state functional connectivity in adolescents and adults.(1), 103−114.

Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders.(3), 406−425.

Moore, S. R., & Depue, R. A. (2016). Neurobehavioral foundation of environmental reactivity.(2), 107−164.

Nava-Gonzalez, E. J., Gallegos-Cabriales, E. C., Leal- Berumen, I., & Bastarrachea, R. A. (2017). Mini-review: The contribution of intermediate phenotypes to G×E effects on disorders of body composition in the new omics era.(9), 1079.

Obradović, J., & Boyce, W. T. (2009). Individual differences in behavioral, physiological, and genetic sensitivities to contexts: Implications for development and adaptation.(4), 300−308.

O’Brien, T. C., Mustanski, B. S., Skol, A., Cook, E. H., & Wakschlag, L. S. (2013). Do dopamine gene variants and prenatal smoking interactively predict youth externalizing behavior?67−73.

Pianta, R. C. (1992).. Unpublished measure, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Pianta, R. C., & Lothman, D. J. (1994). Predicting behavior problems in children with epilepsy: Child factors, disease factors, family stress, and child-mother interaction.(5), 1415−1428.

Pluess, M. (2015). Individual differences in environmental sensitivity.(3), 138−143.

Pluess, M., Assary, E., Lionetti, F., Lester, K. J., Krapohl, E., Aron, E. N., & Aron, A. (2018). Environmental sensitivity in children: Development of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale and identification of sensitivity groups.(1), 51−70.

Pluess, M., & Belsky, J. (2013). Vantage sensitivity: Individual differences in response to positive experiences.(4)901−916.

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies.(5), 879−903.

Poletti, S., Radaelli, D., Cavallaro, R., Bosia, M., Lorenzi, C., Pirovano, A., ... Benedetti, F. (2013). Catechol-O- methyltransferase (COMT) genotype biases neural correlates of empathy and perceived personal distress in schizophrenia.(2), 181−186.

Reuter, M., Frenzel, C., Walter, N. T., Markett, S., & Montag, C. (2011). Investigating the genetic basis of altruism: The role of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism.(5), 662−668.

Roisman, G. I., Newman, D. A., Fraley, R. C., Haltigan, J. D., Groh, A. M., & Haydon, K. C. (2012). Distinguishing differential susceptibility from diathesis-stress: Recommendations for evaluating interaction effects.(2)389−409.

Ru, W., Fang, P., Wang, B., Yang, X., Zhu, X., Xue, M., ... Gong, P. (2017). The impacts of Val158Met in catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) gene on moral permissibility and empathic concern., 52−56.

Sáez, I., Zhu, L., Set, E., Kayser, A., & Hsu M. (2015). Dopamine modulates egalitarian behavior in humans.(7), 912−919.

Slagt, M., Dubas, J. S., van Aken, M. A., Ellis, B. J., & Dekovic, M. (2018). Sensory processing sensitivity as a marker of differential susceptibility to parenting.(3), 543−558.

Smolka, M. N., Gunter, S., Jana, W., Sabine M., Grüsser, H. F., Karl, M., ... Heinz, A. (2005). Catechol-o-methyltransferaseVal158Met genotype affects processing of emotional stimuli in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.(4), 836−842.

Starr, L. R., Hammen, C., Conway, C. C., Raposa, E., & Brennan, P. A. (2014). Sensitizing effect of early adversity on depressive reactions to later proximal stress: Moderation by polymorphisms in serotonin transporter and corticotropin releasing hormone receptor genes in a 20-year longitudinal study.(4)1241−1254.

Stein, D. J., Newman, T. K., Savitz, J., & Ramesar, R. (2006). Warriors versus worriers: The role of COMT gene variants.(10), 745−748.

Wang, M., & Zhang, W. (2010). Association between aggressive behavior and a functional polymorphism in the COMT gene.(8), 1256−1262.

[王美萍, 张文新. (2010). COMT基因多态性与攻击行为的关系.(8), 1256−1262.]

Wang, M., Zheng, X., Xia, G., Liu, D., Chen, P., & Zhang, W. (2019). Association between negative life events and early adolescents’ depression: The moderating effects of Catechol- O-methyltransferase (COMT) Gene Val158Met polymorphism and parenting behavior.(8), 903−913.

[王美萍, 郑晓洁, 夏桂芝, 刘迪迪, 陈翩, 张文新. (2019). 负性生活事件与青少年早期抑郁的关系:COMT基因Val158Met多态性与父母教养行为的调节作用.(8), 903−913.]

Wang, Z. (2022). Environmental sensitivity model on child development: An integrated view.(6), 1367−1374.

[王振宏. (2022). 儿童发展的环境敏感性模型:一种整合的观点.(6), 1367−1374.]

Wang, Z., Wang, X., & Li, C. (2020).Different environmental sensitivity of children: Developmental theory and empirical evidence.36−47.

[王振宏, 王笑笑, 李彩娜. (2020). 儿童发展的不同环境敏感性: 理论与实证.36−47. ]

Weinshilboum, R. (1988). Pharmacogenetics of methylation: Relationship to drug metabolism.(4), 201−210.

Widaman, K. F., Helm, J. L., Castro-Schilo, L., Pluess, M., Stallings, M. C., & Belsky, J. (2012). Distinguishing ordinal and disordinal interactions.(4), 615−622.

Wilson, S., Stroud, C. B., & Durbin, C. E. (2017). Interpersonal dysfunction in personality disorders: A meta-analytic review.(7), 677−734.

Wise, R. A. (2004). Dopamine, learning and motivation.(6), 483−494.

Yan, J., Schoppe-Sullivan, S., & Feng, X. (2019). Trajectories of mother-child and father-child relationships across middle childhood and associations with depressive symptoms.(4)1381−1393.

Zhang, W., Cao, C., Wang, M., Ji, L. Q., & Cao, Y. (2016). Monoamine oxidase a (MAOA) and catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) gene polymorphisms interact with maternal parenting in association with adolescent reactive aggression but not proactive aggression: Evidence of differential susceptibility.(4), 812−829.

Zhang, R., & Wang, Z. (2020). Inhibitory control moderates the quadratic association between resting respiratory sinus arrhythmia and prosocial behaviors in children.(4), e13491.

Zhang, W., Li, X., Chen, G., & Cao, Y. (2021). The relationship between positive parenting and adolescent prosocial behaviour: The mediating role of empathy and the moderating role of the oxytocin receptor gene.(9), 976−991.

[张文新, 李曦, 陈光辉, 曹衍淼. (2021). 母亲积极教养与青少年亲社会行为:共情的中介作用与OXTR基因的调节作用.(9), 976−991.]

Zhang, X. (2011). Parent-child and teacher-child relationships in Chinese preschoolers: The moderating role of preschool experiences and the mediating role of social competence.(2), 192−204.

Zhang, X., Chen, H., Zhang, G., Zhou, B., & Wu, W. (2008). A longitudinal study of parent-child relationships and problem behaviors in early childhood: Transactional models.(5), 571−582.

[张晓, 陈会昌, 张桂芳, 周博芳, 吴巍. (2008). 亲子关系与问题行为的动态相互作用模型: 对儿童早期的追踪研究.(5), 571−582.]

Zhang, Y., Yang, X., & Wang, Z. (2021). The COMT rs4680 polymorphism, family functioning and preschoolers’ attentional control indexed by intraindividual reaction time variability.(4), 713−724.

Zeng, S., & Wang, Z. (2022). Revision of the parent reported Highly Sensitive Child Scale−Chinese version.(1), 101−107.

[曾思瑶, 王振宏. (2022). 中文版父母报告高敏感儿童量表的修订.(1), 101−107.]

The interactive effects of parent-child relationship, sensory processing sensitivity, and theVal158Met polymorphism on preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors

LIU Qianwen, WANG Zhenhong

(School of Psychology, Shaanxi Normal University; Shaanxi Provincial Key Research Center of Child Mental and Behavioral Health, Xi’an 710062)

Prosocial behaviors are voluntary behaviors aimed at benefiting others, which develop rapidly during preschool and provide a foundation for children’s social competence and moral development. According to the person-environment interaction (P×E) framework, children’s traits may interact with the family environment, affecting their prosocial behaviors. Numerous studies have established that parent-child relationship is a crucial component of family psychosocial environments in predicting children’s prosocial behaviors. Sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) is a temperament trait that reflects children’s sensitivity to environmental and social stimuli. Children with high SPS are more susceptible to environmental factors. Furthermore, previous research has suggested that the Val/Val genotype of theVal158Met polymorphism may be a sensitive genotype for prosociality, interacting with environmental factors to influence individuals’ prosocial behaviors. In particular, prior research has proposed that different types of environmental sensitivities, such as temperamental, physiological, and genetic sensitivities, may have a multiplicative effect on social development. Parent-child relationship is an important family psychosocial environmental stimulus. More importantly, two distinct aspects of parent-child relationship, that is, closeness and conflict, may have different functions. Closeness emphasizes the parent-child connection and is characterized by emotional closeness and the sharing of private thoughts and feelings. Conversely, conflict refers to stressful experiences between parents and children that are accompanied by anger or irritation. Therefore, the present study investigated three-way interactive effects of closeness or conflict, SPS, and theVal158Met polymorphism on preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors. Specifically, other hypotheses regarding potential differences in closeness and conflict were formulated.

A total of 507 preschoolers (M= 4.83,= 0.90; 236 girls) were recruited through advertisements at two local kindergartens. Saliva samples for DNA extraction were obtained from preschoolers. Their parents completed questionnaires on parent-child relationship, children’s SPS, and prosocial behaviors. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 24, Mplus 8.3, and R statistical software. First, a test for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and preliminary analyses were conducted. Moreover, linear regression models were conducted, with prosocial behaviors as the dependent variable to test for the main and interactive effects of closeness or conflict, SPS, and genotypes. Sex, age, and family socioeconomic status were included as covariates. The effects of parent-child closeness and parent-child conflict were examined in separate models, but the other dimension of parent-child relationship was controlled in each model. Finally, region of significance and reparameterization regression analyses were employed to examine the optimal shape of the P×E effect.

The results indicated that both parent-child closeness and SPS positively affected preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors (< 0.01), while parent-child conflict was negatively associated with prosocial behaviors (< 0.001). The two-way interaction terms (closeness/conflict × SPS; closeness/conflict × theVal158Met polymorphism; SPS × theVal158Met polymorphism) and the three-way interactive effect of parent-child closeness, SPS, and theVal158Met polymorphism on prosocial behaviors were not significant. However, the effect of parent-child conflict × SPS × theVal158Met polymorphism on prosocial behaviors was significant. We conducted further analyses to compare the interactive effect of parent-child conflict and SPS in preschoolers with the Val/Val and Met+ genotypes on theVal158Met polymorphism. A significant interaction term was observed in Val/Val genotype carriers (= −0.18,= 0.002, 95% CI [−0.304, −0.069]) but not Met carriers (= 0.06,= 0.286, 95% CI [−0.052, 0.167]). The region of significance test indicated that Val/Val genotype carriers with high SPS showed significantly more prosocial behaviors under a low level of parent-child conflict and fewer prosocial behaviors under a high level of parent-child conflict, which supports the differential susceptibility model. The results of the re-parameterized regression models further verified the shape of the interaction effect of parent-child conflict and SPS on preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors.

In summary, the present study signified that different types of sensitivities (temperament and genes) to family stressful environments may have a multiplicative effect on preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors. Furthermore, it suggested that preschoolers with both the sensitive genotype (Val/Val) and sensitive temperament trait (high SPS) were more affected by parent-child conflict and developed prosocial behaviors in a ‘‘for better and for worse’’ manner. The findings provide evidence for the differential susceptibility model and contribute to a further understanding of children’s prosocial behaviors based on the P×E approach, especially from the perspective of children’s multiple sensitivities.

parent-child relationship, sensory processing sensitivity,gene, preschoolers, prosocial behaviors, person × environment interaction

B844; B845

2022-06-23

*国家自然科学基金面上项目(31971004, 32271113)。

王振宏, E-mail: wangzhenhong@snnu.edu.cn