Physical fitness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic:Results of annual national physical fitness surveillance among 16,647,699 Japanese children and adolescents between 2013 and 2021

Tetsuhiro Kidokoro,Grant R.Tomkinson,Justin J.Lang,Koya Suzuki

a Research Institute for Health and Sport Science,Nippon Sport Science University,Tokyo 158-8508,Japan

b Graduate School of Health and Sports Science,Juntendo University,Inzai City 270-1695,Japan

c Alliance for Research in Exercise,Nutrition and Activity(ARENA),University of South Australia,Adelaide,SA 5000,Australia

d Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research,Public Health Agency of Canada,Ottawa,ON K1A 0K9,Canada

e School of Epidemiology and Public Health,University of Ottawa,Ottawa,ON K1H 8M5,Canada

f Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group,Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute,Ottawa,ON K1H 8L1,Canada

Abstract Background:Limited nationally representative evidence is available on temporal trends in physical fitness(PF)for children and adolescents during the coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19)pandemic.The primary aim was to examine the temporal trends in PF for Japanese children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The secondary aim was to estimate the concurrent trends in body size (measured as body mass and height)and movement behaviors(exercise,screen,and sleep time).Methods: Census PF data for children in Grade 5 (aged 10-11 years) and adolescents in Grade 8 (aged 13-14 years) were obtained for the years 2013-2021 from the National Survey of Physical Fitness, Athletic Performance, and Exercise Habits in Japan (n=16,647,699). PF and body size were objectively measured,and movement behaviors were self-reported.Using sample-weighted linear regression,temporal trends in mean PF were calculated before the pandemic (2013-2019) and during the pandemic (2019-2021) with adjustments for age, sex, body size,and exercise time.Results: When adjusted for age, sex, body size, and exercise time, there were significant declines in PF during the pandemic, with the largest declines observed in 20-m shuttle run(standardized(Cohen’s)effect size(ES)= -0.109 per annum(p.a.))and sit-ups performance(ES=-0.133 p.a.). The magnitude of the declines in 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performances were 18-and 15-fold larger, respectively, than the improvements seen before the pandemic(2013-2019),after adjusting for age,sex,body size,and exercise time.During the pandemic,both body mass and screen time significantly increased,and exercise time decreased.Conclusion: Declines in 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performances suggest corresponding declines in population health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Census;Physical inactivity;Public health;Temporal trends;Youth

1. Introduction

On March 11,2020,the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19)outbreak a pandemic.1To mitigate the spread of COVID-19, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency on April 7,2020.While Japan did not have mandatory lockdowns,the government encouraged residents to stay at home and reduce social contact by 70%to 80%.2This caused significant reductions in physical activity (PA)among the Japanese population,particularly during the first state of emergency (April 7 through May 25, 2020).3In particular, it was expected that the movement behaviors of children(PA,sedentary behavior, and sleep) would be adversely affected by a series of restrictions (e.g., cancelation of sporting events and organized sports participation) after the government declared a temporary closure of schools on March 2, 2020.2Preliminary evidence indicated that PA levels declined and screen time increased among Japanese school-aged children during the pandemic (2021) as compared to before the pandemic (2019).4,5Additionally, recent reviews summarizing the international evidence from the first year of COVID-19 found that lockdown restrictions led to reduced PA,increased screen time,and altered sleep patterns, with a shift to later bed and wake times among children and adolescents.6,7

Physical fitness (PF) is an important marker of current and future health.8-10Preliminary evidence from small samples of youth suggested that lockdown measures had significant adverse effects on PF among children and adolescents.11-19For example,Wahl-Alexander et al.14reported significant declines in the 20-m shuttle run(-26.7%),sit-ups(-19.4%),and push-ups(-35.6%)performance of 264 children in the United States(mean age=9.6 years) during lockdown. Similarly, Chambonni‵ere et al.15found a significant lockdown-related decline in the 20-m shuttle run,standing long jump,medicine ball throw,and motor skill performance of 206 French primary school children (mean age = 9.9 years). These findings, while important, are not generalizable to their respective country populations because of their small samples,which were identified using non-probability sampling procedures. To date, only a single study has used nationally representative data to identify declining PF levels. A Slovenian study found that after only 2 months of lockdown, PF had declined in 6- to 15-year-old Slovenian children by 13%; these were the lowest PF levels seen in 30 years of national monitoring.18Unfortunately, the effect of lockdown restrictions on Slovenian children was only reported for a composite PF measure(comprising 8 distinct PF measures) rather than for individual components. Additionally, no study to date has examined the temporal trends in PF before and during the COVID-19 pandemic while adjusting for important covariates, such as age, sex, and PA.Furthermore,the effects of COVID-19-related restrictions on PF have only been reported for European11,12,15-19and American children;13,14no study has examined these effects in Asian children and adolescents.

Temporal trends in the PF levels of children and youth may help understand the impact of existing population-based intervention strategies, the impact of social change (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic), and provides insight into current and future population health. This is particularly important since PF among children and adolescents tracks moderately well into adulthood and is associated with current and future health.8-10In 2008, Japan launched its National Survey of Physical Fitness, Athletic Performance, and Exercise Habits(hereafter called the JP Fit Survey for Youth). While this survey is limited to students in Grades 5 and 8, nearly all students have completed PF testing annually(i.e.,approximately 2 million per annum (p.a.)) with an average response rate between 2013 and 2021 of 97% at the school level.20Therefore, unlike most studies using probability sampling, the JP Fit Survey for Youth recruited all students across Japan and so provided a complete annual picture of the PF levels among Japanese children and adolescents.20Additionally,the JP Fit Survey for Youth includes 8 PF tests and provides detailed data on PF levels before and during the pandemic according to these individual components.The aim of this study,therefore,was to use the JP Fit Survey for Youth data to examine temporal trends in PF levels(adjusted for age,sex,body size,and exercise time)for Japanese children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The secondary aim was to estimate concurrent trends in body size(height and body mass) and movement behaviors (exercise,screen,and sleep time).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the Japanese PF survey

The JP Fit Survey for Youth is a census survey,administered annually between May and July to approximately 2 million Japanese children (Grade 5; age = 10-11 years) and adolescents(Grade 8,age=13-14 years).A detailed description of the survey has been published previously.20Although data collection for the JP Fit Survey for Youth began in 2008, this study used data from 2013 onwards due to inconsistency in the sampling strategy during the 2008-2012 period.20Additionally, the 2020 PF survey was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In total, PF data from 16,647,699 participants (Grade 5: 8,490,558 children(49% girls); Grade 8: 8,157,141 adolescents (49% girls)) were available between 2013 and 2021.20

The survey includes objectively measured PF, height, and body mass, plus self-reported movement behaviors (exercise,screen, and sleep time). In schools, PF was commonly measured by classroom or physical education teachers using standardized protocols21,22for the following 8 tests: handgrip strength, sit-ups, sit-and-reach, side-step, 20-m shuttle run,50-m sprint, standing long jump, and ball throw (softball for Grade 5 students and handball for Grade 8 students). Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital weighing scale, and standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer.All students were invited to participate in the PF tests, but some did not participate for the following reasons: (a) those who were prohibited or restricted from exercising by a medical doctor, and (b) those who were unwell(e.g.,fever or undue fatigue)on the day of PF testing.

Questionnaires were also administered in school by classroom or physical education teachers. Self-reported exercise time was quantified using the following question: “Usually,how long do you play sports or exercise outside of physical education classes?” Participants quantified time spent participating in exercise for all days of the week (Monday through Sunday), and average daily exercise time was calculated by dividing total time by 7.Recreational screen time was quantified using the following question: “On school days, how long do you spend watching television, playing video games, or using your smartphone or computer, other than for homework?” As per the 24-h movement guidelines,23recreational screen time was classified as “meeting” (<2 h/day) or “not meeting” (≥2 h/day) the recommendation. Sleep was quantified by asking participants the number of hours they sleep per day,with cut-points of ≥9 h for Grade 5 and ≥8 h for Grade 8 as per the 24-h movement guidelines.23

2.2. Data analyses

Descriptive results (e.g., sample sizes, means, standard deviation (SD), and percentage meeting 24-h guidelines) at the grade and sex levels were reported annually and used in our analysis.Temporal trends before (2013-2019) and during (2019-2021)the COVID-19 pandemic were analyzed using sample-weighted linear regression models relating the year of testing to mean PF(8 PF tests) and body size (height and body mass). Linear models were used because they naturally summarized the overall temporal trends. Temporal trends in PF and body size were estimated by adjusting for (a) age and sex (Model 1), and (b) age, sex, body size (height and body mass), and exercise time (Model 2).24We expressed the overall linear trends in means as absolute trends(i.e.,the regression coefficient),percent trends(i.e.,the regression coefficient expressed as a percentage of the sample-weighted mean value for all means in the regression), and as standardized(Cohen’s)effect sizes(ES)(i.e.,the regression coefficient divided by the pooled SD for all values in the regression).Positive trends indicated temporal increases/improvements, and negative trends indicated temporal declines.Additionally,trends in mean exercise time and the percentage of children/adolescents meeting or not meeting the 24-h guidelines for sleep and sedentary behavior23were also calculated.

Distributional variability was quantified as the coefficient of variation(CV)(i.e.,the ratio of the SD to the mean).Trends in CVs were analyzed as the ratio of CVs by dividing the 2019 CV by the 2013 CV (before pandemic) and the 2021 CV by the 2019 CV(during pandemic)using the procedure described elsewhere.25,26Ratios >1.1 indicated substantial increases in variability (i.e., the magnitude of variability in relation to the mean increased over time), ratios < 0.9 indicated substantial declines in variability(i.e.,the magnitude of variability in relation to the mean decreased over time), and ratios between 0.9 and 1.1 indicated negligible trends in variability(i.e.,the magnitude of variability in relation to the mean did not change substantially over time).27

3. Results

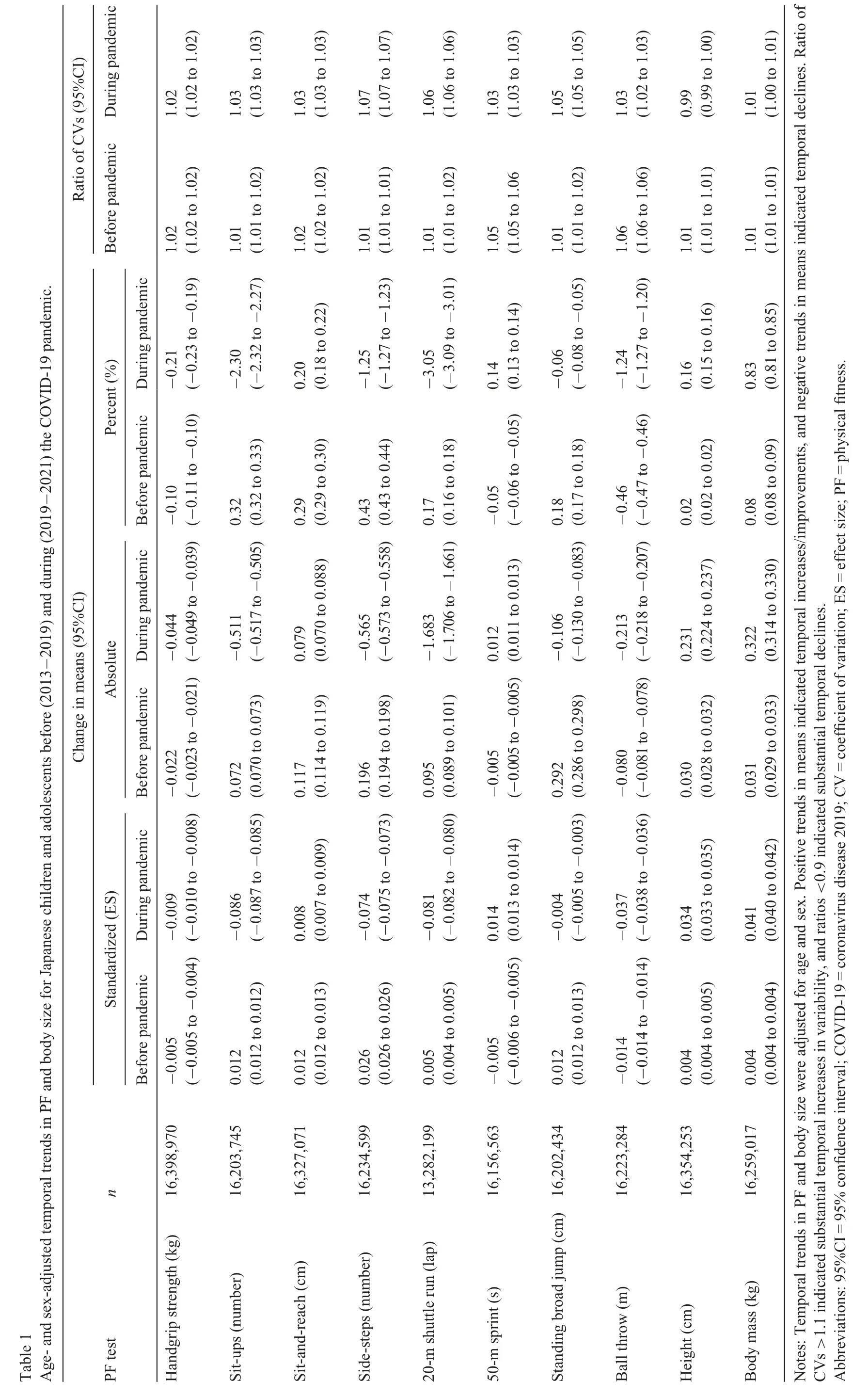

Age-and sex-adjusted temporal trends in PF and body size before and during the COVID-19 pandemic are shown in Table 1. There were significant trends for all PF measures before and during the pandemic. Some trended upward through 2019 before declining sharply in 2021. For example,the 20-m shuttle run performance improved steadily before the pandemic (ES=0.005 p.a.) but declined at a 16-fold larger rate during the pandemic(ES=-0.081 p.a.).Similarly,the situps performance was improving before the pandemic(ES=0.012 p.a.) but then declined at a 7-fold larger rate during the pandemic (ES=-0.086 p.a.). Similar trends were observed for all age-sex groups(Supplementary Tables 1-4).For other PF measures,the before- and during-pandemic temporal differences were considerably smaller (<3-fold). Body mass increased before and during the pandemic,with a 10-fold larger increase during the pandemic. There were negligible trends in variability for all PF and body size measures before and during the pandemic.

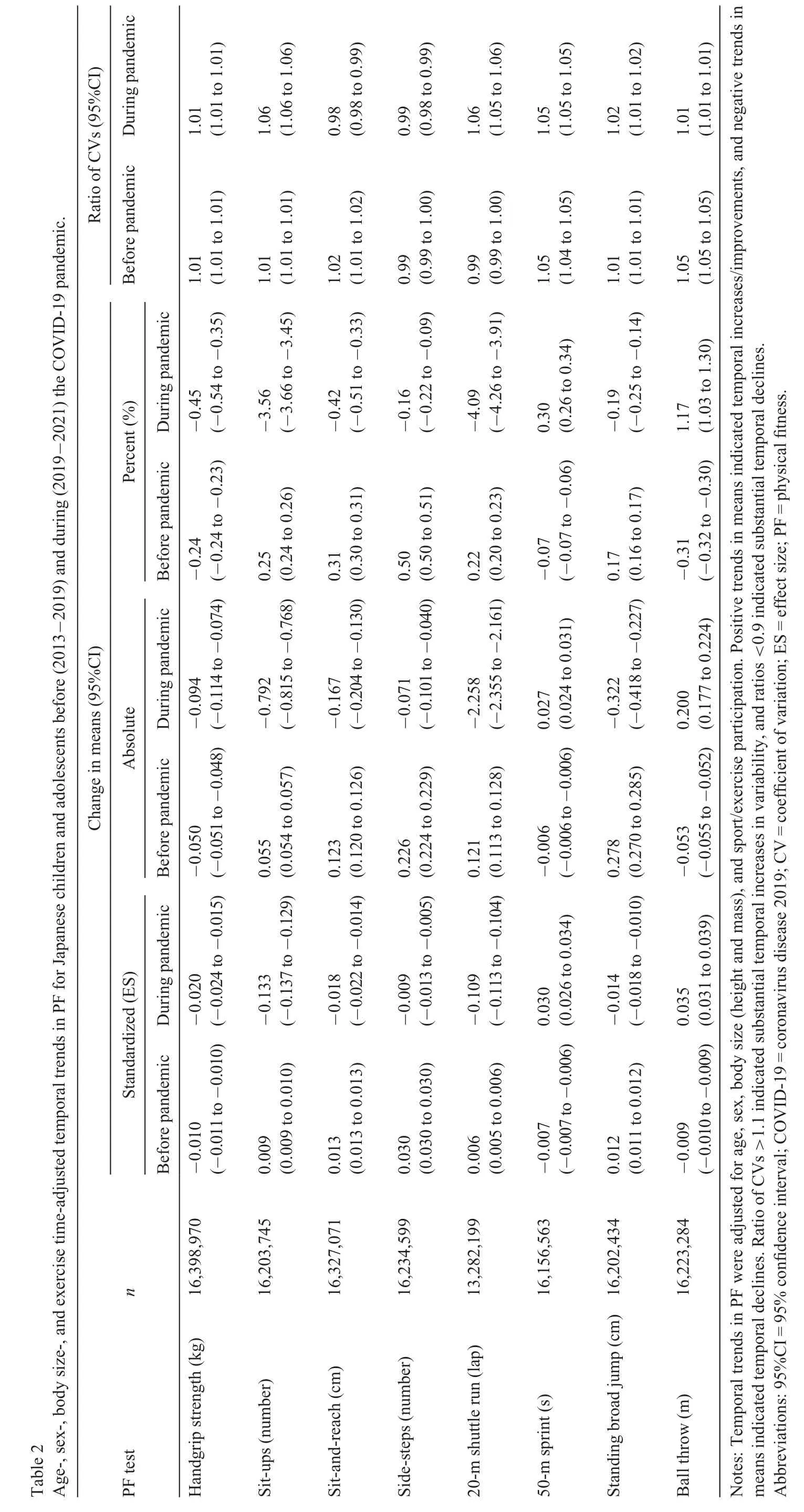

Age-,sex-,body size-,and exercise time-adjusted PF trends before and during the COVID-19 are shown in Table 2.Similar trends emerged as with the age- and sex-adjusted trends,which reversed from pre-pandemic increases to decline sharply during the pandemic. Both 20-m shuttle run(ES=0.006 p.a.) and sit-ups (ES=0.009 p.a.) performance improved before the pandemic but afterward declined at considerably higher rates (18-fold (ES= -0.109 p.a.) and 15-fold(ES=-0.133 p.a.),respectively).Temporal differences before and during the pandemic were<4-fold for other PF measures.

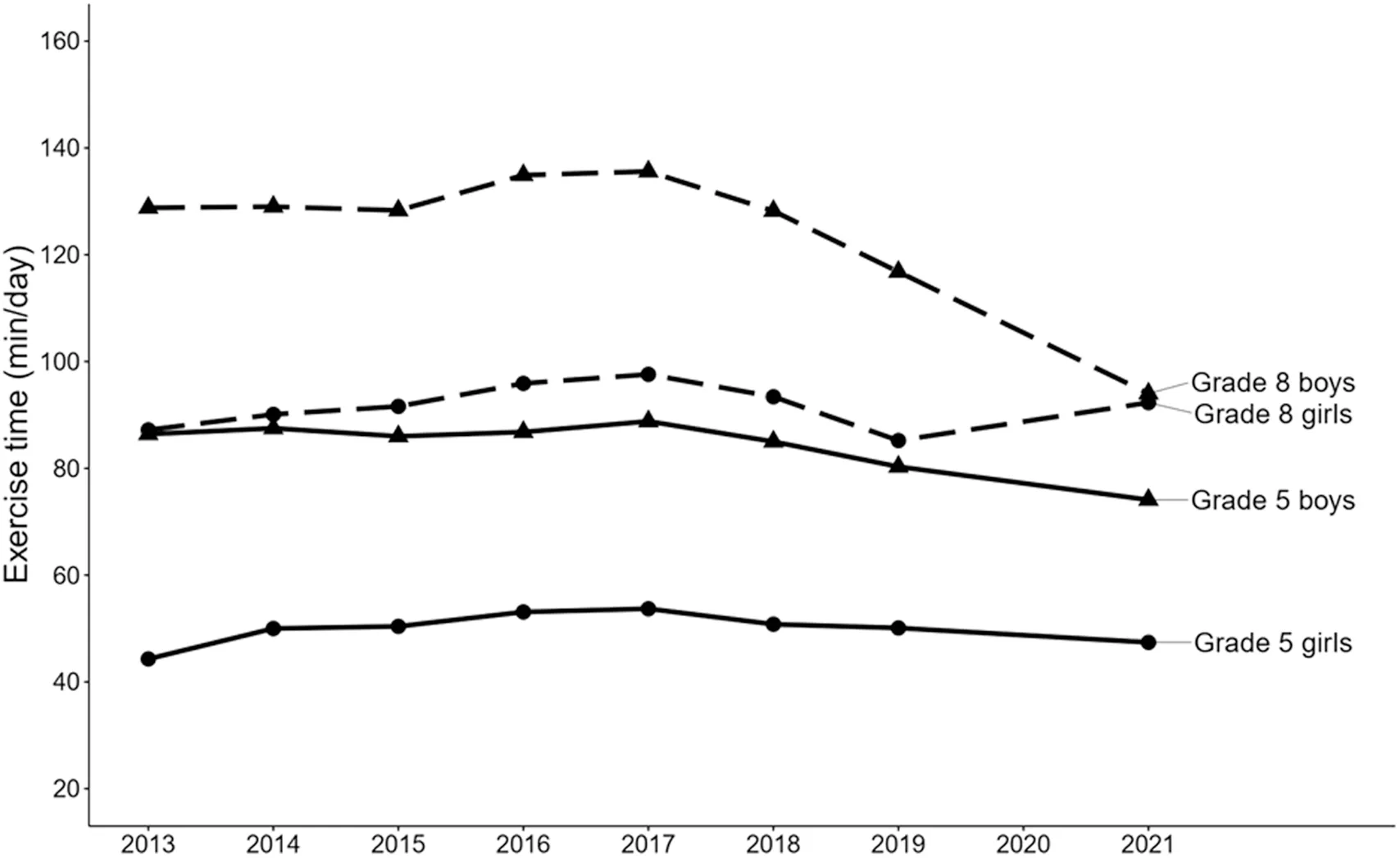

In Fig. 1, trends in mean exercise time between 2013 and 2021 are shown as trends in absolute values(min/day)because SD and sample size data were unavailable.There was a decline in exercise time among children and adolescents (except for Grade 8 girls), with grade- and sex-specific rates of decline ranging from-5.5% to-19.6% during the pandemic(2019-2021). There were negligible trends in variability for all adjusted PF measures before and during the pandemic.

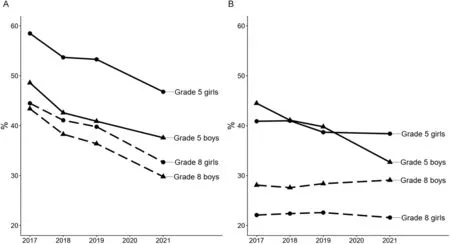

The percentages of children and adolescents who met the screen time (<2 h/day) and the sleep time guidelines(≥9 h/day for Grade 5, ≥8 h/day for Grade 8) are shown in Fig. 2. Collectively, there was a steady decline in the percentage of children and adolescents who met the screen time guideline, with grade-and sex-specific rates of decline ranging from-1.7% to-3.5% during the pandemic(2019-2021) and from-2.5% to-3.9% before the pandemic(2017-2019).The percentage of children and adolescents meeting the recommended sleep guidelines remained steady from 2017 to 2021. Descriptive statistics for PF by grade and sex between 2013 and 2021 are shown in Supplementary Table 5.

Fig.2. Temporal trends in the percentage of Japanese children and adolescents who met the(A)screen time and(B)sleep guidelines before(2017-2019)and during(2019-2021)the COVID-19 pandemic.Screen time and sleep were self-reported.Annual trends in the percentage of Japanese children and adolescents meeting(A)the recreational screen time guideline of<2 h/day and(B)sleep guidelines(≥9 h/day for Grade 5 and ≥8 h/day for Grade 8).23 COVID-19=coronavirus disease 2019.

4. Discussion

We examined trends in the PF levels of a census sample of 16,647,699 Japanese children and adolescents before(2013-2019) and during (2019-2021) the COVID-19 pandemic. The principal findings were (a) that PF generally declined during the pandemic and at larger rates than before,and(b)the 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance declined at rates considerably higher (>15-fold) than before the pandemic after adjusting for age, sex, body size, and exercise time.Declines in 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance are of concern to public health given these measures are significantly associated with present and future health outcomes among children and adolescents.8-10,28-30

4.1. Explanation of main findings

Fig.1. Temporal trends in mean exercise time for Japanese children and adolescents before (2013-2019) and during (2019-2021) the COVID-19 pandemic.Exercise time was self-reported.The 2020 PF survey was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19=coronavirus disease 2019; PF =physical fitness.

Declines in 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance during the pandemic were considerable when compared to before the pandemic levels, and when compared to international trends. For example, the decline in 20-m shuttle run performance during the pandemic was 18-fold larger than the improvement seen before the pandemic when adjusted for age, sex, body size, and exercise time. Among Japanese children and adolescents, the decline in 20-m shuttle run performance during the pandemic was 27-fold larger than the international decline of-0.004 ES p.a. that took place between 2010 and 2014.31Similarly, the age-, sex-, body size-, and exercise time-adjusted decline in sit-ups performance during the pandemic was 15-fold larger than the before-pandemic improvement, and 11-fold larger than the international decline of-0.012 ES p.a. that occurred between 2010 and 2017.32In contrast, the decline in standing long jump performance during the pandemic was 2-fold smaller than the international decline of-0.03 ES p.a.between 2010 and 2017.33These results suggest that declines in 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance among Japanese youth were considerable during the pandemic,which is cause for concern. Similar findings were observed in Slovenian children during the pandemic, with endurance performance (long distance running) showing the largest declines and muscle power performance (standing long jump) showing the smallest.18Also consistent with these findings are the results from a study of children living in the Miyagi prefecture after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake(this prefecture was one of the most affected areas34).Researchers saw larger declines in the 20-m shuttle run(ES=-0.09 p.a.)and sit-ups performance(ES=-0.07 p.a.)compared to other PF performance tests (ES: handgrip strength=-0.01 p.a.; sit-and-reach=-0.05 p.a.; sidesteps=-0.02 p.a.; 50-m sprint=-0.03 p.a.; standing broad jump=-0.03 p.a.;and ball throw=-0.05 p.a.).35

It is a challenge to explain why performances on endurance PF (longer duration) tests, such as the 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups,were more affected during the pandemic than other PF(short duration) tests, such as the standing long jump and handgrip strength. We have previously argued that temporal trends in PF performance are probably caused by a network of environmental, social, behavioral, psychosocial, and/or physiological factors.31,36Several recent studies have found declines in body-size adjusted 20-m shuttle run37and sit-ups38performances, which suggest that declines in PA levels have influenced the declines in PF. No study to our knowledge has examined temporal trends in 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance while statistically adjusting for trends in PA levels.Our novel finding of declines in age-, sex-, body size-, and exercise time-adjusted 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance indicate that factors other than increased body size and reduced exercise time are probably at play.Systematic reviews have found consistent positive associations between vigorous PA and both cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF)39and muscular endurance.40Given that only the duration,not the intensity,of exercise time was self-reported in the JP Fit Survey for Youth,it is possible that long duration vigorous PA levels among Japanese schoolchildren declined during,but not before, the pandemic. It is also possible that pandemic-related restrictions(e.g., school/recreation facility closures and organized sports cancellations/restrictions) impacted the quantity and intensity of physical education,active play,active transportation,and/or muscle strengthening activities, resulting in larger declines in 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance during the pandemic compared to beforehand. For example, in Japan, unlike in other countries, organized sport in school settings is highly popular,and the majority of Japanese children and adolescents participate in organized sport at school.41However, after the outbreak of the pandemic, most organized sports activities were cancelled for several months. The restrictions, such as reduced practice time, continued for more than a year. This starved children and adolescents of PA opportunities, including vigorous intensity and continuous types of PA(both maximal and sub-maximal PA).42In contrast, since children’s PA patterns are generally intermittent (as opposed to continuous)in nature,43pandemic-related changes in intermittent PA may have been minimal compared to changes in endurance (aerobic) PA. This may help explain why other PF measures were less affected during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance.

4.2. Comparisons with other studies

Previous studies examining the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on PF among children and adolescents have also found a negative effect,although the magnitude of the declines in PF varied between studies.11-19We do note that all studies,11-17,19with the exception of one,18recruited small non-probability samples of youth,ranging from 10 to 764 children and adolescents, which may explain the between-study differences.Such between-study differences could also be due to differences in participant pools, policy decisions on school and sport closures, timing of testing, test methodologies, as well as changes in movement behaviors during the pandemic.Our study builds on previous findings by providing the most complete national picture of the COVID-19 pandemic-related impact on PF, using annual census PF data on Japanese children and adolescents since 2013. Our study found significant declines in PF,which along with declines in exercise time and percentage of school children meeting screen time guidelines,suggest an overall decline in population health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.3. Future efforts to restore pre-pandemic PF levels

While the long-term effects of COVID-19-related restrictions are unknown and need further investigation,declines in PF during the COVID-19 pandemic,particularly with respect to CRF,may negatively impact population health. Low CRF, specifically,tracks moderately well from childhood into adulthood44-46and is significantly associated with all-cause mortality in later life.10,47Therefore,there is a pressing need to help Japanese children and adolescents return to pre-pandemic PF levels.Japan was succeeding in its approach to improving population PF levels,as demonstrated by the pre-pandemic improvements we found in most PF components, including CRF (measured as 20-m shuttle run performance in this study). Therefore, relaxing pandemic restrictions may help restore pre-pandemic PF levels. On the other hand,the COVID-19-related restrictions provide an opportunity for Japan to reimagine PA by complementing structured PA with informal and unstructured PA.Although Japan’s unique culture of organized school sport activities should be maintained,international experts also recommend increasing PA opportunities by promoting informal and unstructured PA activities at home, in the community, and in non-school settings.48Such an approach may improve population PF levels, especially among those not currently involved in organized sport.49

4.4. Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths.First,we used annual census PF data from the annual JP Fit Survey for Youth surveillance system for all Grades 5 and 8 Japanese students between 2013 and 2021. The school-level participation rate in the PF surveillance system has been consistently near perfect since 2013 (average = 97.0%). These data allowed us to estimate national trends in PF for Japanese children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic with very high statistical power. Additionally, our analytical approach enabled us to examine trends in PF while statistically adjusting for important covariates, including age, sex, body size, and exercise time. While we used only summary statistics (since raw data were not available), our trends (and corresponding 95%confidence intervals (95%CIs)) were not biased compared to those based on individual-level regression.24

The limitations of this study include missing data from 2020 due to COVID-19 lockdowns.This lack of data meant we could not determine continuous trends between May-July 2019(before pandemic) and May-July 2021 (during pandemic).Therefore, while the time course of the trends in PF during the pandemic is unclear(e.g.,Did PF steadily decline or drastically decline and then plateau/improve?), our linear regression approach did provide an overall summary. Second, our trends may not be generalizable to all Japanese children and adolescents(i.e.,those not in Grades 5 and 8).Understanding whether trends in PF during the pandemic differed for those at different developmental stages would help determine whether targeted or generalized initiatives are required. Third, movement behaviors were self-reported and may be inaccurate.For example,the exercise time question used in the JP Fit Survey for Youth reportedly overestimates PA levels when compared to accelerometry.50Additionally,only the duration of each movement behavior was estimated(exercise,screen,and sleep time)with neither the type nor the content evaluated (e.g., intensity (moderate, vigorous)and domain(school vs.non-school PA,weekday vs.weekend)).Trends in self-reported measures may also suffer from recall or response bias.51Furthermore,since only the mean exercise time statistics were presented in the surveillance report (no SD and sample size data were available), we were unable to determine the statistical significance of such trends. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the JP Fit Survey for Youth has used the same questions every year since 2013 (for exercise) and 2017(for screen time and sleep).

5. Conclusion

We found general declines in PF levels for Japanese children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the largest declines occurring in 20-m shuttle run and sit-ups performance. Given that these PF measures are significantly associated with present and future health, these declines suggest corresponding declines in population health due to the pandemic-related restrictions implemented in Japan. Japan’s annual national surveillance of PF for children and adolescents is unique.It not only provides insight into the negative effects of COVID-19-related restrictions on PF,it also predicts future disease burden and highlights potential opportunities to engage cost-effective public health surveillance strategies. Moving forward, efforts must be made to help Japanese children and adolescents return to pre-pandemic PF levels.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgment

Supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Scientific Research(C) (20K11450 to KS) and by Institute of Health and Sports Science&Medicine,Juntendo University.

Authors’contributions

TK developed the research question,designed the study,led the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript; GRT designed the study,led the statistical analysis,and helped draft the manuscript;JJL led the statistical analysis and helped draft the manuscript; and KS developed the research question,designed the study, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2022.11.002.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2023年2期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2023年2期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Exercise training-induced changes in exerkine concentrations may be relevant to the metabolic control of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients:A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Stair climbing,genetic predisposition,and the risk of incident type 2 diabetes:A large population-based prospective cohort study

- Twenty-four-hour movement guidelines during middle adolescence and their association with glucose outcomes and type 2 diabetes mellitus in adulthood

- The effects of a 20-week exercise program on blood-circulating biomarkers related to brain health in overweight or obese children:The ActiveBrains project

- Dose-dependent associations of joint aerobic and muscle-strengthening exercise with obesity:A cross-sectional study of 280,605 adults

- Chronotropic incompetence is more frequent in obese adolescents and relates to systemic inflammation and exercise intolerance