Use of anticoagulation reversal therapy in the emergency department: a single-center real-life retrospective study

Jacopo Davide Giamello, Andrea Pisano, Fabrizio Corsini, Remo Melchio, Luca Bertolaccini, Enrico Lupia, Giuseppe Lauria

1 School of Emergency Medicine, University of Turin, Turin 10100, Italy

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, Santa Croce e Carle Hospital, Cuneo 12100, Italy

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Santa Croce e Carle Hospital, Cuneo 12100, Italy

4 Department of Thoracic Surgery, IEO, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, Milan 20141, Italy

5 Department of Emergency Medicine, Città della Salute e della Scienza Hospital, Turin 10126, Italy

6 Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin 10100, Italy

The incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) and deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (DVT/PE) has increased in the last decades as a consequence of global aging and the refinement of diagnostic techniques; thus, the consumption of anticoagulant drugs has increased significantly.[1,2]Prescriptions of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have overtaken those of vitamin K antagonists (VKA) since the mid-2010s.[3]Consequently, the incidence of these drugs’ side effects has also increased; the most relevant side effect in terms of morbidity and mortality is bleeding. In addition to critically ill bleeding patients, another indication of anticoagulant reversal therapy is the need for emergency surgery or for a procedure with a high risk of bleeding.[4]In these situations, it is possible to use antidotes to restore the coagulation balance; idarucizumab, a specific antidote for the reversal of dabigatran, is available; and andexanet-alfa, a specific antidote for factor Xa inhibitors, has recently been approved in Europe, but its use in clinical practice is not yet widespread.[5]In addition, reversal therapy can be performed with the use of non-specific reversal agents such as prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) containing three-factor prothrombin complex concentrates (3F-PCCs) or four-factor prothrombin complex concentrates (4F-PCCs). Although some guidelines (mostly based on expert opinions) for anticoagulant reversal therapy have been published, their use in real life is a little-studied topic.[6]We aimed to analyze the use of reversal therapy in an emergency department (ED) to evaluate the outcome of the treated patients.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective observational single-centre study conducted in the ED of the Santa Croce e Carle Hospital in Cuneo, a teaching hub hospital in northwest Italy.

We included all patients undergoing anticoagulation reversal therapy over two years (from January 1st, 2018, to December 31st, 2019). The indication for reversal therapy was classified as follows: (1) trauma-related major bleeding; (2) spontaneous major bleeding; and (3) the need for urgent surgery or operative procedures.

Major bleeding was defined as the presence of at least one of the following: (1) bleeding at a critical site (central nervous system hemorrhage, pericardial tamponade, airways, hemothorax, intra-abdominal bleeding, retroperitoneal hematoma, intramuscular and intra-articular bleeding); (2) hemodynamic instability; and (3) clinically overt bleeding with hemoglobin decrease >2 g/dL.

The primary outcome was all-cause 30-day mortality; we also assessed all-cause mortality at 48 h and three months after admission. This study complied with theDeclaration of Helsinkiand was approved by the local ethics committee. The manuscript was written according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement.[7]

RESULTS

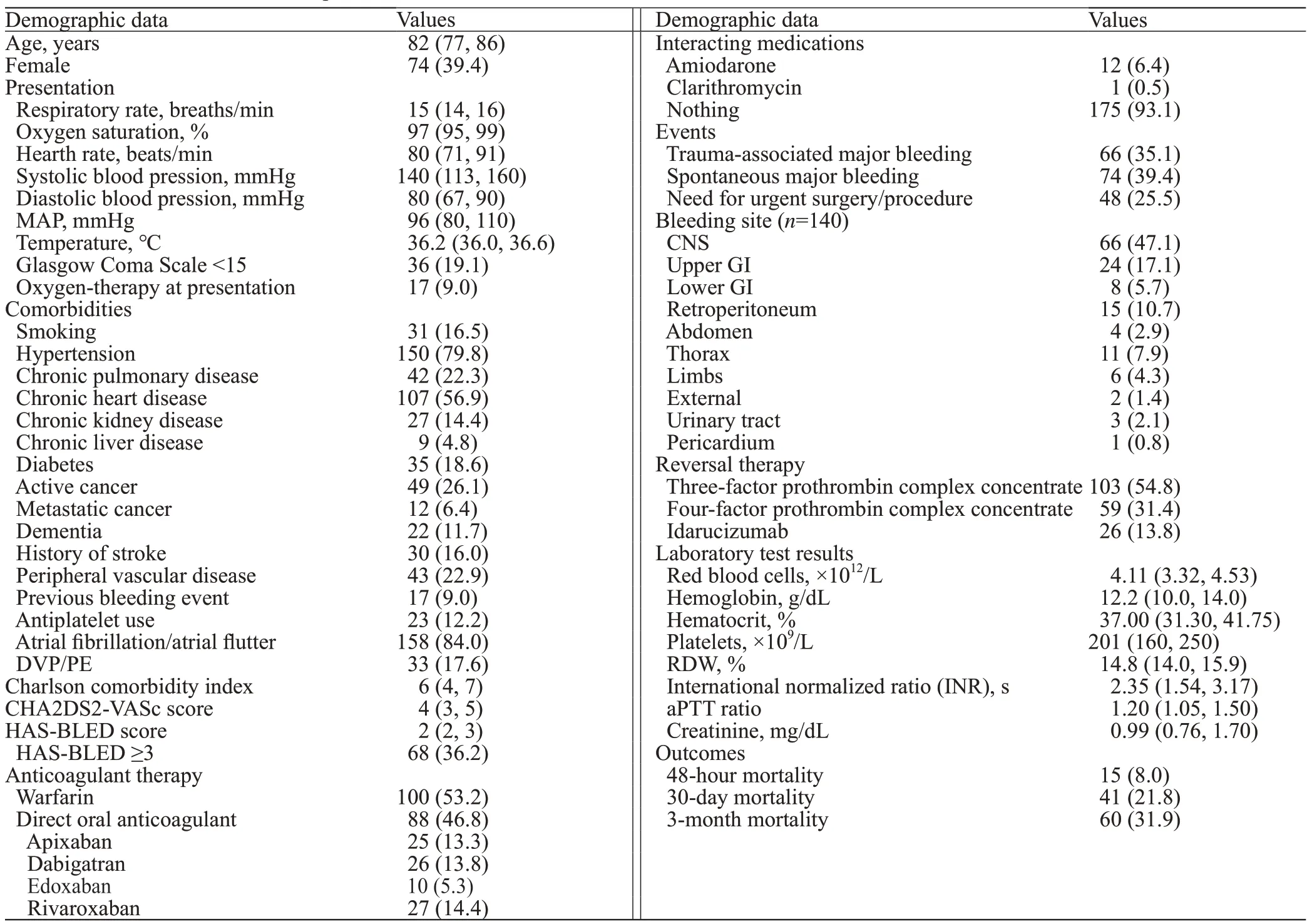

In the studied period, 188 requests for an antidote for the reversal of anticoagulation were made. The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Almost 65% of patients were 80 years old or older, with a male/female ratio of 1.54. Almost 20% of patients had an altered state of consciousness at presentation, and 5.3% had a mean arterial blood pressure below 65 mmHg (1 mmHg=0.133 kPa). Approximately 36.2% of patients had a Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol concomitantly (HAS-BLED) score ≥3. The indications for the reversal of anticoagulation were major bleeding associated with trauma (35.1%), spontaneous major bleeding (39.4%), and the need for urgent surgery or an urgent procedure (25.5%). The central nervous system (47.1%) was the most frequent bleeding site, followed by the gastrointestinal tract (22.8%).

Univariate analysis identified the following variables significantly associated with 30-day mortality: age greater than 80 years (P=0.046), lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at presentation (P<0.001), metastatic cancer (P=0.002), higher Charlson comorbidity index (P=0.019), hemoglobin <12.2 g/dL (P=0.043) and higher red blood cell distribution width (RDW) (P=0.014).

We found no differences in mortality when comparing patients with different indications of reversal therapy. In addition, no mortality differences were detected considering either the type of anticoagulant (warfarin vs. DOACs) or the site of bleeding.

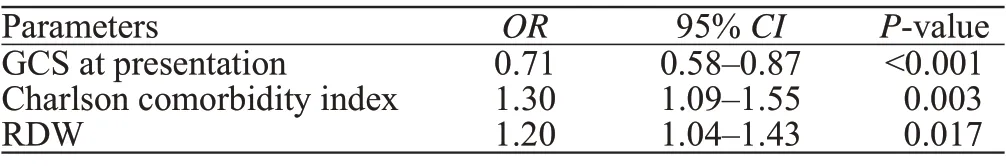

Independent predictors of 30-day mortality were GCS score at presentation, Charlson comorbidity index score and RDW (Table 2). This predictive model had a concordance (C)-statistic of 0.75.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

Table 2. Multivariable model

DISCUSSION

In our experience, patients who require reversal therapy are elderly and often have several comorbidities, as highlighted by the high median Charlson comorbidity index; this may explain the high mortality we observed. Surprisingly, nearly 40% of patients were considered at high risk of bleeding with a validated tool such as the HAS-BLED score.[8,9]

All patients on dabigatran were treated with idarucizumab; most patients on VKA were treated with 3F-PCC, while most patients on DOACs received 4F-PCC. It should be noted thatandexanet-alfa was unavailable in Italy in the studied years. The guidelines suggest using specific antidotes (idarucizumab and andexanet-alfa) if available; alternatively, 4F-PCC should be used; for VKA-related bleeding, the use of 4F-PCC is indicated as well.[3]However, there is no evidence that 4F-PCC reduces mortality compared to 3F-PCC, although 4F-PCC appears to be more effective in stabilizing INR.[10]However, the cost per administration is significantly lower for 3F-PCC, and both are approved for VKA reversal therapy.

The GCS was found to be a strong predictor of mortality; it reflects patients’ acute neurological impairment; a low GCS value may depend on the severity of intracranial bleeding or on major bleeding leading to cerebral hypoperfusion. Some comorbid conditions and advanced age were also associated with increased mortality; these variables are summarized in the Charlson comorbidity index value, which accurately reflects the state of frailty due to past medical history. The role of the GCS and Charlson comorbidity index in predicting mortality is biologically prominent, reflecting the severity of the acute event and the chronic status of the patient, respectively; on the other hand, the predictive power of RDW is surprising. RDW is a measure of anisocytosis and is routinely reported in the complete blood cell counts; it is available to all patients at no cost. RDW has already been associated with worse clinical outcomes in a previous study for chronic and acute diseases.[11]It has been described that higher RDW values correlated with increased mortality in patients with trauma and particularly traumatic brain injury; moreover, RDW was higher in trauma patients admitted to the ED than that in healthy patient controls.[12]RDW expresses the presence of pathological stress resulting in high red blood cell turnover. Anisocytosis is closely related to infl ammation and oxidative stress;[13]these events can occur in trauma patients with severe bleeding and in those who need urgent surgery.

Our study has limitations, particularly its retrospective and monocentric design; the sample size is modest, although it is considerable in this field, and has not been widely explored with real-life studies thus far.

In conclusion, anticoagulation reversal therapy is often needed in the ED for patients with ongoing major bleeding or an indication for urgent surgery or procedures that cannot be safely delayed. These patients are often elderly and have several comorbidities; in fact, the mortality of these patients is relatively high, probably because of their frailty. In addition to the GCS and Charlson comorbidity index (an indicator of patient’s general condition), RDW, a little-used and low-cost parameter, is a strong predictor of poor prognosis.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:This study complied with theDeclaration of Helsinkiand was approved by the local ethics committee.

Confl icts of interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Contributors:JDG wrote the main body of the article. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study.

World journal of emergency medicine2023年1期

World journal of emergency medicine2023年1期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Patient care during interfacility transport: a narrative review of managing diverse disease states

- Endothelial cell metabolism in sepsis

- Nutritional status and prognostic factors for mortality in patients admitted to emergency department observation units: a national multi-center study in China

- Prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation improves long-term prognosis for acute coronary syndrome: five-year results from a large cohort study

- Efficacy and safety of remimazolam-based sedation for intensive care unit patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a cohort study

- Glutamine supplementation attenuates intestinal apoptosis by inducing heat shock protein 70 in heatstroke rats