Nutritional status and prognostic factors for mortality in patients admitted to emergency department observation units: a national multi-center study in China

Hai-jiang Zhou, Dong-jing Zuo, Da Zhang, Xin-hua He, Shu-bin Guo

Nutrition School of Education College of Chinese Emergency Medicine, Beijing Key Laboratory of Cardio-pulmonary Cerebral Resuscitation, Emergency Medicine Clinical Research Center, Beijing Chao-yang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China

KEYWORDS: Nutritional risk; Malnutrition; Nutritional Risk Screening 2002; Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form

INTRODUCTION

The general decline in the fertility rate and increase in life expectancy have led to an upsurge in the elderly population worldwide.[1]According to the Seventh National Population Census in China, there are 264 million individuals in the age group 60 years and over, accounting for 18.7% of the total population.[2]The problem of the large aging population in China affects the economy, placing huge financial burdens on the healthcare system and posing a major challenge for Chinese society in the decades to come.

The frequency of disability increases with aging. As one ages, health problems accumulate, and people begin to lose their ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL).[3,4]Inadequate nutrition contributes to the progression of many diseases and is also regarded as an important contributing factor in the complex etiology of sarcopenia and frailty.[5]Malnutrition or risk of malnutrition is reported in up to 30% and 50% of community dwellers and in-hospital patients, respectively.[6]Appropriate nutritional therapy can assist in preventing disease-related or age-related disabilities and in accelerating recovery from illness or surgery.[6]As an independent risk factor that can negatively influence patients’ clinical outcomes, hospital malnutrition is becoming a clinical concern. Malnutrition and its risk should be routinely and systemically screened in all patients at hospital admission using validated tools.[5]Currently, the most common validated nutritional screening tools include the Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form (MNA-SF), Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002), and the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index.[7-9]

Owing to the special medical insurance model in China, elderly patients with disability and multi-system comorbidities are among the groups that most frequently visit the emergency department (ED), and these patients have longer stays in the ED observation unit (EDOU).[10]The failure to provide older patients with any nutritional therapy incurs the risk of underfeeding during their recovery course. Timely NRS and appropriate treatment are of vital importance to improve the bed turnover rate and reduce patient mortality. Despite its large population, until now, few comprehensive studies have been conducted in China concerning the nutritional status of patients admitted to the EDOU. We therefore conducted this multi-center study to investigate nutritional status and explore the prognostic factors of mortality in patients admitted to EDOUs in China.

METHODS

lnclusion and exclusion criteria of patients

EDOUs from 90 tertiary public hospitals in China (42 cities in 23 provinces, province-level municipalities, and autonomous regions) were invited to participate in this study, and 2,627 patients admitted between June 2020 and December 2020 were enrolled during recruitment. The inclusion criteria were length of stay (LOS) in the EDOU for more than 48 h, age older than 18 years, and the patient or their relatives agreeing to participate in this study. The following patients were excluded from this study: those with LOS in the EDOU for less than 48 h, age less than 18 years, refusal to participate in this study, patients with incomplete medical records (e.g., incomplete demographic information or laboratory examination results that could influence the calculation of Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE II], MNA-SF, and NRS 2002 scores), pregnant patients, or those with an unclear prognosis.

Data collection

Case report forms to collect information regarding the nutritional status of patients were distributed and completed by the attending physicians. For all enrolled patients, we collected demographic and other information (sex, age, diagnosis, comorbidities, consciousness status, body mass index [BMI], triceps skinfold thickness [TST]), vital signs [body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and transcutaneous oxygen saturation]), and laboratory data at admission. Laboratory parameters included whole blood cell count (white blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count), biochemistry examination (albumin, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, sodium, potassium), and arterial blood gas analysis (pH value, arterial partial pressure of oxygen and carbon dioxide, oxygenation index). Nutritional support therapies were also recorded, including oral nutritional supplements (ONS), enteral nutrition (EN), parenteral nutrition (PN), and the combination of EN and PN (EN+PN) during patients’ stay in the EDOU. The APACHE II, MNA-SF, and NRS 2002 scores for each patient were calculated and recorded at admission. All patients were followed up for 28 d, and 28-day mortality was recorded. Patients were divided into a survival group and a mortality group according to the outcome.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables with a normal distribution are expressed as the mean±standard deviation and were compared using thettest or one-way analysis of variance. Data with a skewed distribution are presented as the median (interquartile range) and were compared using the Mann-WhitneyUnonparametric test. Categorical variables are described as numbers and percentages and were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., USA). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were carried out, and the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) was compared using MedCalc 15.0 software (Acacialaan, Belgium) to evaluate and compare the predictive ability of age, APACHE II, NRS 2002, MNA-SF, consciousness, heart failure, and combined predictors. According to the cutoff values, we also calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. TheZ-test was used to compare the AUROCs among different ROC curves. Univariate and multi-variate logistic regression analyses were performed to screen and assess potential independent risk factors for mortality. The Bonferroni correction method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. A two-tailedP-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of enrolled patients

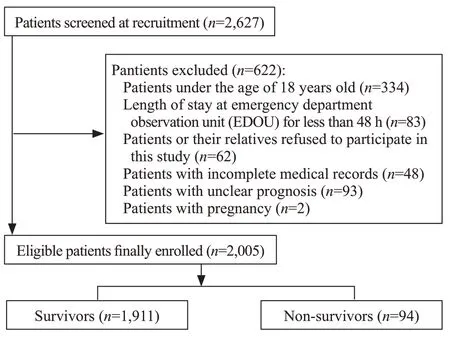

A total of 2,627 patients were evaluated at recruitment, and 622 patients were excluded (Figure 1). A total of 2,005 eligible patients who met all the inclusion criteria were finally included in our study. Among them, 1,196 (59.65%) patients were men, and 809 (40.35%) were women. At the 28-day follow-up, 1,911 patients survived, and 94 died (supplementary Table 1).

Patients were divided into three groups according to BMI: <18.5 kg/m2, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2and ≥25 kg/m2, accounting for 15.06%, 64.84%, and 20.10% of the total population, respectively (supplementary Table 1). In total, 1,046 patients had APACHE II scores <15, and 959 patients had APACHE II scores ≥15 at admission (supplementary Table 1). Patients were divided into three groups according to their NRS 2002 score at admission: a group with a score of 1-2 points (n=450), a group with a score of 3-4 points (n=1,043), and a group with a score of 5-7 points (n=512) (supplementary Figure 1).

Comorbidities of the enrolled patients are shown in supplementary Table 1 and supplementary Figure 2. Patients were divided into three groups according to the number of commorbidities: patients with no comorbidity, patients with one comorbidity, and patients with two or more comorbidities. As for nutritional support therapy, the number of patients receiving ONS, EN, PN, and EN+PN were 425, 314, 853 and 413, respectively, with patients receiving PN accounting for the majority (42.54%) (supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients enrolled in this study.

Nutritional status of enrolled patients

Totally 1,555 (77.55%) patients had a nutritional risk (NRS 2002 ≥3, and 512 (25.53%) patients had a high nutritional risk (NRS 2002 ≥5) (supplementary Figure 1).

In the age group >80 years old, the proportion of patients with high nutritional risk (NRS 2002 ≥5) was 29.00% (136/469); this proportion was significantly higher than that in the age group 66-80 years (290/1212, 23.93%,P=0.032) but not significantly higher than that in the age group 18-65 years (86/324, 26.54%,P=0.449) ( supplementary Figure 3).

The proportion of patients with high nutritional risk (NRS 2002 ≥5) was 27.94% (19/68), 25.43% (193/759), and 25.47% (300/1178) in the three comorbidity groups, respectively, with no significant difference between any two groups (supplementary Figure 4). In the proportion with high nutritional risk, we found significant differences between patients with clear consciousness and altered consciousness (21.23% vs. 35.35%,P<0.001) and patients with admission APACHE II scores <15 and ≥15 at admission (37.66% vs. 71.03%,P<0.001).

In terms of malnutrition (MNA-SF ≤7), with increased age group, the proportion of patients with malnutrition (11.73% vs. 15.02% vs. 18.12%) increased, as did the number of comorbidities (13.24% vs. 14.62% vs. 15.70%). The patients with the age >80 years (18.12%) and patients with two or more comorbidities (15.70%) had the highest malnutrition rate. The malnutrition rate among patients with altered consciousness was significantly higher than that of patients with clear consciousness (18.33% vs. 13.85%,P<0.01). There was also a significant difference between patients with an admission APACHE II score <15 and those with scores ≥15 (12.62% vs. 18.04%,P<0.01).

Status of nutritional support therapy

The proportion of patients receiving ONS as nutritional therapy increased with increased patient age (16.67% for age 18-65 years, 20.05% for age 66-80 years, and 27.29% for age >80 years), BMI (14.43% for <18.5 kg/m2, 20.48% for 18.5-24.9 kg/m2, and 28.57% for ≥25 kg/m2), and number of comorbidities (7.35% in the group with no comorbidity, 18.58% with one comorbidity, and 23.68% with two or more comorbidities). The proportion of patients taking ONS in the group with age >80 years, with BMI ≥25 kg/m2, and with two or more comorbidities was significantly higher than that of the other two age groups (P<0.01), the other two BMI groups (P<0.05), and the other two comorbidity groups (P<0.05) (supplementary Table 1). The proportion of patients taking ONS as nutritional therapy among patients with clear consciousness or APACHE II score <15 was significantly higher than that in patients with altered consciousness (27.62% vs. 6.55%,P<0.01) or patients with APACHE II score >15 (30.31% vs. 11.26%,P<0.01).

The proportion of patients receiving PN or EN+PN as nutritional therapy decreased with increased age (65.44% for age 18-65 years, 64.60% for age 66-80 years, and 57.78% for age >80 years), BMI (70.49% for <18.5 kg/m2, 64.30% for 18.5-24.9 kg/m2, and 53.94% for ≥25 kg/m2) and number of comorbidities (75.00% for no comorbidity, 68.64% for one comorbidity, and 58.92% for two or more comorbidities). The proportion of patients receiving PN or EN+PN in the group with age >80 years, with BMI ≥25 kg/m2group, and with two or more comorbidities was significantly lower than the proportions in the other two age groups (P<0.05), the other two BMI groups (P<0.05), and the other two comorbidity groups (P<0.05). The proportion of patients receiving PN or EN+PN among patients with clear consciousness or those with APACHE II score <15 was significantly lower than that among patients with altered consciousness or APACHE II score ≥15 (60.41% vs. 70.07%,P<0.001).

Mortality rate comparisons among different groups

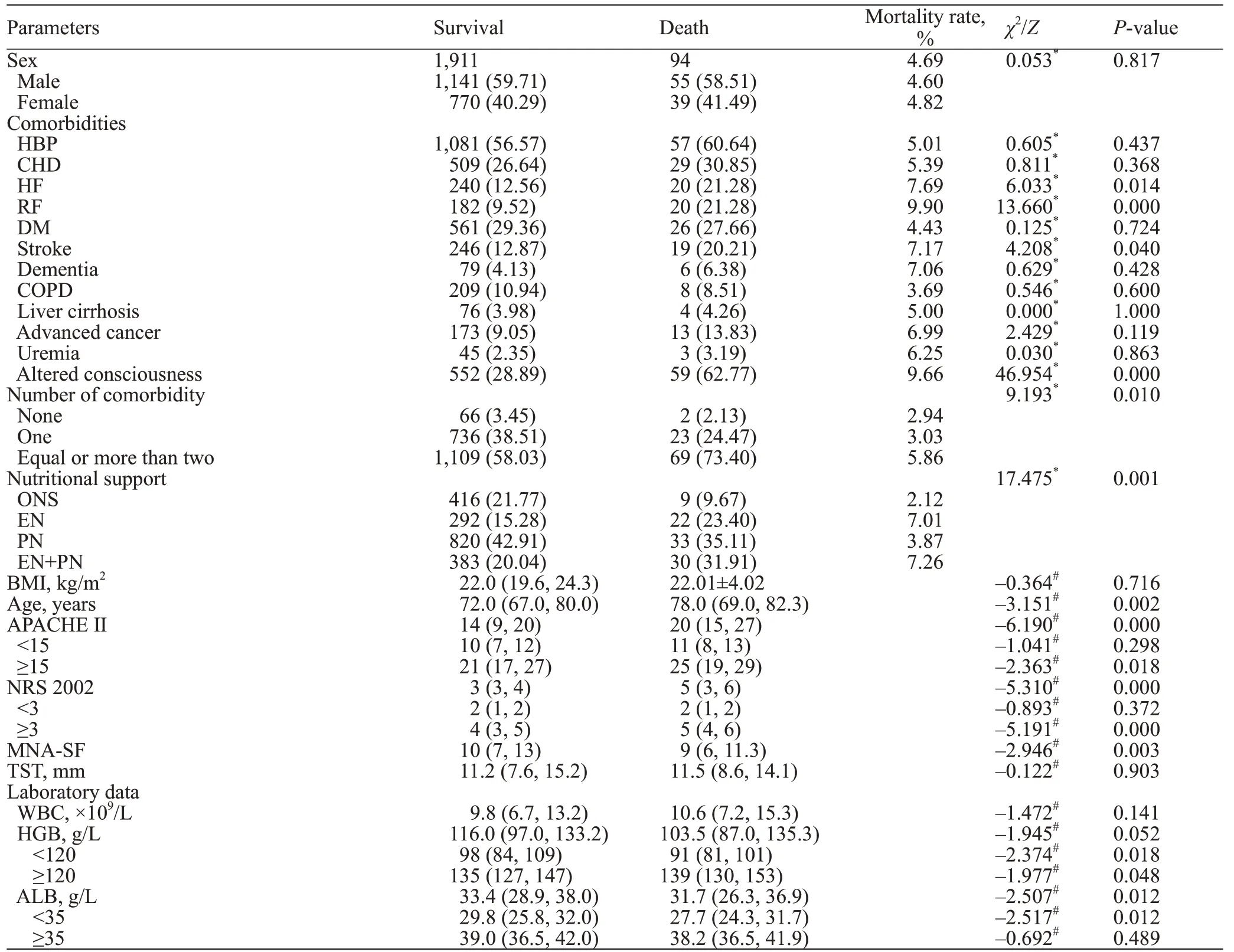

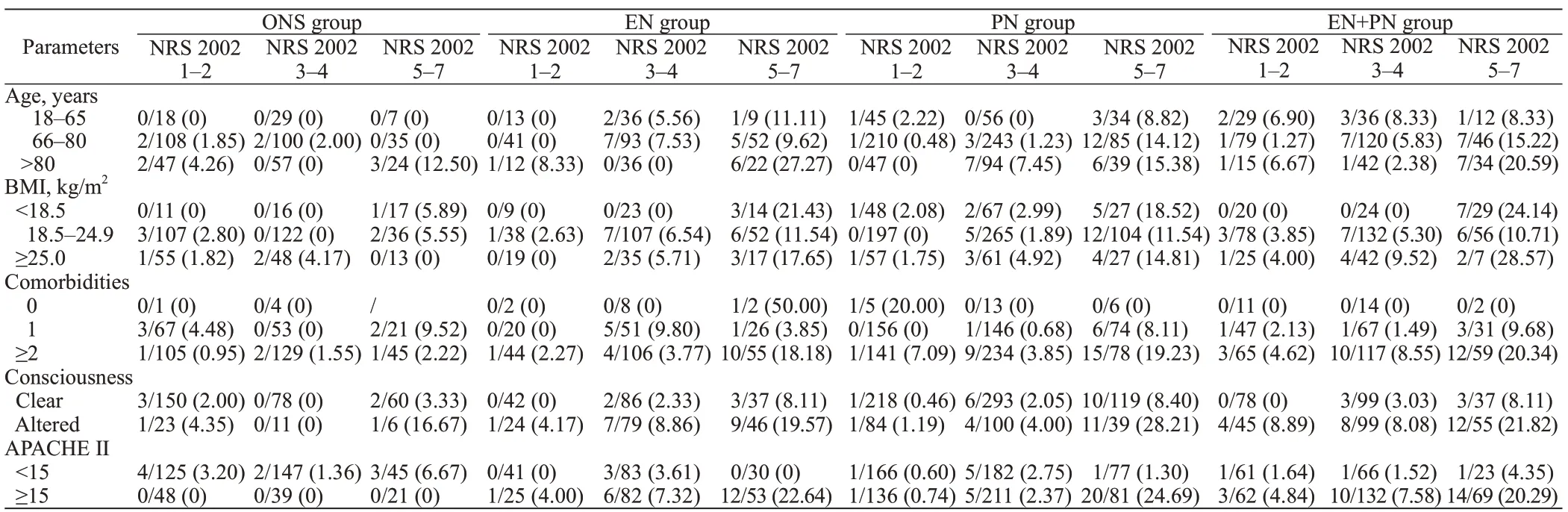

The mortality rate among patients aged >80 years and those with two or more comorbidities was significantly higher than that in the other two age groups (P=0.004;P=0.011) and the other two comorbidity groups (P=0.004;P<0.001); there was no significant difference among the three BMI groups (P=0.081;P=0.144;P=0.746, respectively) in terms of mortality rate (Table 1 and supplementary Figure 3). The mortality rate in patients with high nutritional risk (NRS 2002 ≥5) was significantly higher than that in patients with low nutritional risk (NRS 2002 between 3 and 4) (P<0.01) or with no nutritional risk (NRS 2002 <3) (P<0.01). The differences in values for BMI, APACHE II, NRS 2002, MNA-SF, and TST by sex and age groups are shown in supplementary Figures 5-9.

Prognostic risk factors for mortality

The results of univariate analyses demonstrated that heart failure, respiratory failure, stroke, altered consciousness, number of comorbidities, nutritional support therapy, age, APACHE II, NRS 2002, MNA-SF, and albumin level were potential influencing factors in 28-day mortality (Table 2). Further multi-variate binary logistic regression analysis revealed that heart failure (odds ratio [OR]=1.856, 95%CI1.087-3.167,P=0.023), consciousness (OR=2.967, 95%CI1.894-4.648,P<0.001), APACHE II score (OR=1.037, 95%CI1.017-1.058,P<0.001), NRS 2002 score (OR=1.286, 95%CI1.115-1.483,P=0.001), and MNA-SF score (OR=0.946, 95%CI0.898-0.997,P=0.039) were all independent risk factors for 28-day mortality among patients admitted to the EDOU ( supplementary Table 2, supplementary Figure 10).

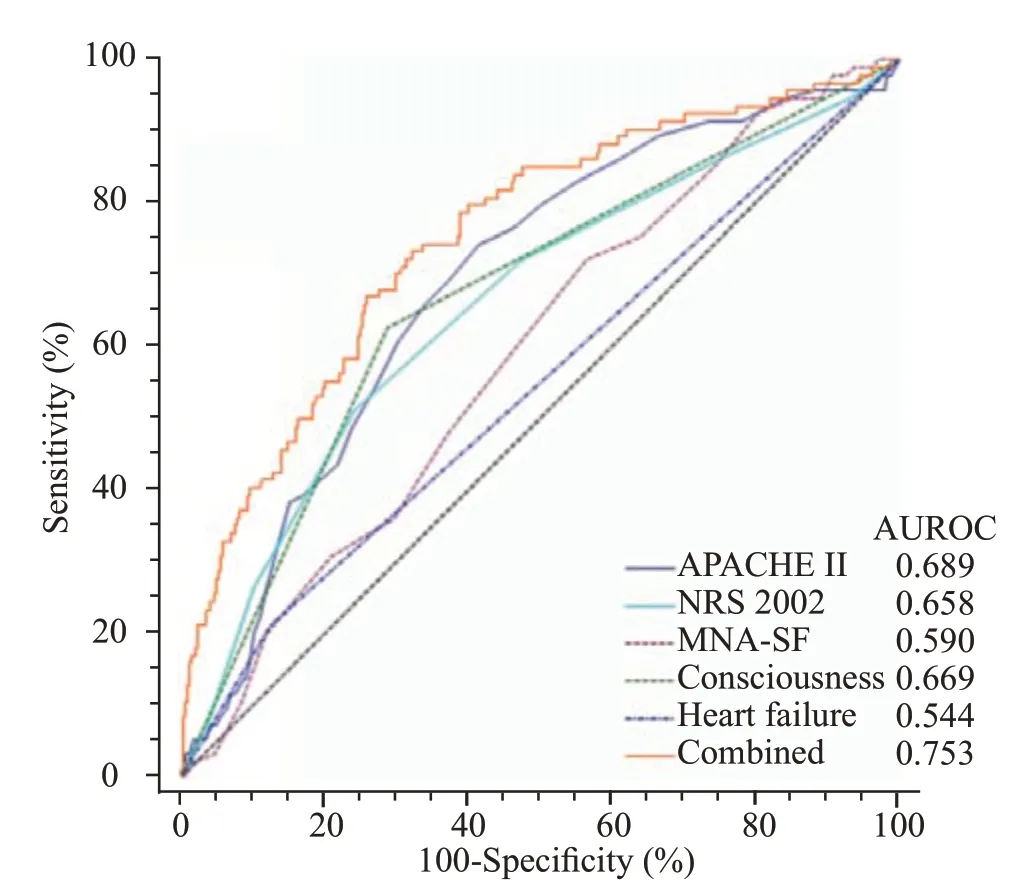

In predicting 28-day mortality, the AUROC of APACHE II (0.689) was the highest, followed by NRS 2002 (0.658), age (0.596) and MNA-SF (0.590) (supplementary Table 3). Pairwise comparisons among different single predictors revealed that there were no significant differences between APACHE II and NRS 2002 (Z=0.851,P=0.395), NRS 2002 and age (Z=1.481,P=0.139), or age and MNA-SF (Z=0.163,P=0.871). APACHE II and NRS 2002 scores had similar predictive ability for mortality and were both superior to other single predictors. The AUROC of the combined model using APACHE II, NRS 2002, MNA-SF scores as well as consciousness and heart failure was 0.753; the predictive performance of the combined model was superior to any single predictor (allP<0.05) (Figure 2).

Table 2. Univiarate analysis of risk factors for mortality

Figure 2. ROC curve comparisons of predictors in predicting mortality.

Table 1. Mortality comparisons among different NRS 2002 and nutritional support therapy groups

DISCUSSION

The numbers of ED visits and observations are currently increasing in most tertiary hospitals of China; a similar trend has also been found in the USA.[10-12]With aging populations growing globally, older people comprise the largest proportion of patients admitted to the EDOU. A lack of knowledge about nutritional therapy among medical staffincreases the nutritional risk for patients in the EDOU, which could prolong their LOS and lead to a poor prognosis.

Our analyses revealed that about 84% of patients were more than 65 years old, and about 97% had one or more comorbidities. Moreover, about 78% of patients had nutritional risk, and 26% had high nutritional risk. There may be several reasons for this. The rapid growth of the economy in China has led to more people switching from consuming high-carbohydrate and high-fiber foods to consuming highfat and high energy-density foods.[13]These unhealthy foodshave important roles in the development of overweight and obesity, contributing to the morbidity of chronic diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and stroke. The sequelae of these chronic diseases could influence food intake among these patients. Elderly patients are more prone to chronic diseases that can lead to inadequate intake of nutrients, thereby leading to malnutrition and sarcopenia and making patients refractory to treatment.

Aging is accompanied by increased comorbidity, functional decline, and an increased prevalence of geriatric syndromes manifesting as frailty, falls, immobility, incontinence, and delirium.[14]Advanced age is also associated with an increased risk of malnutrition, characterized by a reduction in nutrient intake or nutrient absorption.[15]Our study results support those of previous research. With increased patient age and more comorbidities, the nutritional risk also increased. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nutritional status among older adults revealed that the prevalence of malnutrition differed significantly across healthcare settings and individuals’ dependency levels, from 3.1% for those living in the community to 17.5% among those in care homes and 28.7% among patients in long-term care.[15]A study by Saka et al[16]found that malnutrition risk showed a positive correlation with the number of existing geriatric syndromes, whereas depression, dementia, functional dependence, and multiple comorbidities were associated with poor nutritional status. Similarly, patients with severe conditions in our study (e.g., altered consciousness or APACHE II score >15) had higher nutritional risk or a higher proportion with malnutrition (85.2% vs. 75.4%; 84.2% vs. 71.4%). Owing to severe catabolism caused by stress-related and proinflammatory cytokines and hormones, the nutritional status of critically ill patients can deteriorate rapidly, even when patients are well nourished.[17]The importance of nutrition in the hospital setting, especially for critically ill patients, is crucial to understand because nutrition therapy can help attenuate patients’ metabolic response to stress, prevent oxidative cellular injury, and favorably modulate immune responses.[18]

Nutrition is an important modulator of health and well-being; however, for various reasons, nutritional intake is often compromised in elderly people.[5]ONS are energy- and nutrient-dense products designed to increase dietary intake when the normal diet alone cannot meet the daily nutritional requirement.[5]Older hospitalized patients with malnutrition or a risk of malnutrition should be offered ONS to improve dietary intake and body weight and to lower the risk of complications, readmission, and functional decline.[5]A systematic review and metaanalysis involving 36 randomized controlled trials provided evidence that high-protein ONS can yield these clinical benefits.[19]Moreover, administration of standard ONS in the hospital setting has the advantage of cost savings and is cost-effective in patients with different ages, nutritional statuses, and underlying conditions.[20]EN is the first choice for elderly patients with normal gastrointestinal function. Nutritional formulas and the best route for EN should be tailored to each patient in consideration of their age, comorbidities, and nutritional risk.[21]PN is an alternative choice for patients with gastrointestinal function deficiency and intolerance of the gastrointestinal tract.[21]The beneficial effects of EN compared with PN have been well documented in randomized controlled trials involving a variety of patient populations with critical illness.[19]Despite no obvious difference in mortality, EN showed superiority in reducing infectious morbidity (e.g., pneumonia, central line infections) and ICU LOS.[18,22]EN is now recommended as the preferred route for early nutrition therapy in critically ill adults compared with PN.[23]In this research, the proportion of patients receiving ONS increased, and the proportion of patients receiving PN or the combination of EN and PN decreased with increased patient age. This is mainly because patients in the age group 18-65 years had a higher proportion of diagnosed gastrointestinal disorders that required fasting and interim PN before recovery in comparison with the other two age groups. Moreover, patients in the older age group had more comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, and stroke at the same time). This could help elucidate why more patients with two or more comorbidities were taking ONS and fewer were receiving PN or EN+PN. Moreover, patients with severe conditions or those who are critically ill (e.g., patients who are hemodynamically unstable, unconscious, or in shock) cannot take ONS themselves, so the proportion of patients receiving PN or EN+PN was higher in these patients. Early EN is recommended to be initiated within 24-48 h among critically ill patients who are unable to maintain volitional intake. In settings of hemodynamic compromise or instability, EN should be maintained until the patient is fully resuscitated.[18]

Frailty can be observed in adults of all ages but is closely tied to aging.[24]Malnutrition is associated not only with physical and cognitive impairment, poor quality of life, morbidity, and mortality in elderly populations, but also with higher levels of frailty.[24]Optimal management of nutrition can improve frailty, making malnutrition a modifiable risk factor in relation to frailty.[24]Gentile et al[25]proved that malnutrition is the strongest independent risk factor predicting short-term mortality in elderly patients presenting to the ED and that malnutrition is easily detected using the MNA-SF and can be supported during the ED visit. A study including 2,465 adult patients in the ED found that hypoalbuminemia, high C-reactive protein levels, and NRS 2002 score ≥3 were independent predictors of mortality.[26]The NRS 2002 score has been proven to be a strong and independent risk score for malnutrition-related mortality and adverse outcomes, particularly in patients with high nutritional risk who have an NRS 2002 score ≥5.[27-29]According to the nutritional score domain of the NRS 2002, patients receive one point if they have had weight loss greater than 5% in the past 3 months or food intake between 50% and 75% of their nutritional needs. For patients over age 70 years, one additional point is awarded for weight loss of more than 5% in the past 3 months or food intake between 50% and 75% of nutritional needs, leading to the diagnosis of nutritional risk.[8]Reduced oral intake and weight loss are very common in patients admitted to the EDOU, especially elderly patients.

The MNA was developed for certain subgroups, especially elderly people, before changes in weight or albumin occur. The MNA-SF incorporates only six of the original 18 items; this scale was designed as a simpler and more practical screening tool because the original MNA is complex and time-consuming.[7,30]The MNA-SF has been validated and has sensitivity and specificity as high as those of the original MNA.[30]However, overestimation may occur when the MNA-SF is used. Additionally, the need for caregivers to help patients complete the scale, especially for questions regarding weight loss and evaluation of cognitive factors and disabilities, is a disadvantage in using the MNASF.[30]Our study results were consistent with previous research in that the NRS 2002 performed better than the MNA-SF in predicting mortality (AUROC 0.658 vs. 0.590,P=0.0499).[30]Helminen et al[31]concluded that the MNASF was superior to the NRS 2002 in predicting short-term outcomes of hip fracture. Nonetheless, the study results are contradictory, so the prognostic value of the NRS 2002 and MNA-SF for mortality remains unclear.[30]

The prognosis of elderly patients is often influenced by their underlying state of health, defined as consciousness, nutritional status, and functional capacity (level of independence in ADL). Deterioration of these aspects has been proven to be an independent risk factor for mortality in elderly patients. Our study revealed that APACHE II, NRS 2002, and MNA-SF scores as well as consciousness and heart failure were all independent risk factors for mortality among patients admitted to the EDOU. APACHE II and NRS 2002 scores had a similar AUROC, indicating that they had similar predictive ability for mortality; both scales were superior to other single predictors. APACHE II, a well-known and commonly used tool to assess prognosis, classifies the severity of disease using physiological parameters. The scale has been proven to be a good predictor for hospital clinical outcomes. Higher scores represent a more severe disease state and higher mortality rate.

Our study results provide a reference for further indepth research and will help to enhance awareness among medical staff about nutritional support therapies for patients admitted to the EDOU. Nonetheless, some limitations exist in our research. Although EDOUs from 90 hospitals in China participated in this study, only 20 to 30 patients were enrolled in each center. The sample sizes in each center therefore cannot fully represent the characteristics of each EDOU and could result in selection bias. Second, a proportion of patients with incomplete clinical data were not included in our study, which could lead to an incomplete analysis of data from all patients. Finally, prognostic factors determining patient mortality are diverse, and nutritional status is only one of them. Additional aspects must be considered in future studies. With the rapid advancement and wide application of artificial intelligence and big data technology in routine clinical practice, more in-depth studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to further validate our study results.

CONCLUSIONS

Nutritional risk is prevalent among EDOUs in China. APACHE II and NRS 2002 scores are important risk factors for mortality in patients admitted to the EDOU in China. Enhancing awareness about nutritional risk as well as appropriate screening and timely intervention measures can reduce mortality and improve prognosis in patients admitted to the EDOU. Our study results warrant further research to better understand the effects of nutrition on patients admitted to the EDOU.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our sincere gratitude for the cooperation of the superb medical staffparticipating in this study from all 90 emergency department observation units in China.

Funding:This study was supported by the research fund of “Clinical Application Value Exploration of Standard Diagnosis and Treatment Pathway and the Database of Clinical Decision Support System for Acute Pancreatitis in Emergency Department”. We also thank the support from FRESENIUS KABI SSPC.

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing Chao-yang Hospital, Capital Medical University (2021-Ke-456). Written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients or their relatives.

Confl icts of interest:None.

Contributors:HJZ and DJZ are both first authors and they contributed equally to this article. HJZ, XHH, and SBG: conceptualization; HJZ: data curation, formal analysis, and writing-original draft; HJZ, DJZ, DZ, YL, and XHH: investigation; HJZ, XHH, and SBG: methodology; XHH and SBG: supervision; HJZ and XHH: writing-review & editing.

All the supplementary files in this paper are available at http://wjem.com.cn.

World journal of emergency medicine2023年1期

World journal of emergency medicine2023年1期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Modified qSOFA score based on parameters quickly available at bedside for better clinical practice

- Hyoscine N-butylbromide inhalation: they know, how about you?

- Occurrence of Boerhaave’s syndrome after diagnostic colonoscopy: what else can emergency physicians do?

- A case of chemical eye injuries and aspiration pneumonia caused by occupational acute chemical poisoning

- A case of unusual acquired factor V deficiency

- A case of persistent refractory hypoglycemia from polysubstance recreational drug use