Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome induced by tacrolimus following liver transplantation: Three case reports

Jia-Yun Jiang, Yu Fu, Yan-Jiao Ou, Lei-Da Zhang

Jia-Yun Jiang, Yan-Jiao Ou, Lei-Da Zhang, Institute of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Southwest Hospital, Third Military Medical University (Army Medical University), Chongqing 400038,China

Yu Fu, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS) is a rare complication in solid organ transplant recipients, especially in liver transplantation recipients. However, the consequences of HSOS occurrence are pernicious, which could result in severe liver or renal failure, and even death. In addition to previously reported azathioprine and acute rejection, tacrolimus is also considered as one predisposing factor to induce HSOS after liver transplantation, although the underlying mechanism remains unclear.CASE SUMMARY In this study, we reported three cases of tacrolimus-related HSOS after liver transplantation. The diagnosis of HSOS was firstly based on the typical symptoms including ascites, painful hepatomegaly and jaundice. Furthermore, the features of patchy enhancement on portal vein and delayed phase of abdominal enhanced computed tomography were suspected of HSOS and ultimately confirmed by liver biopsy and histological examination in two patients. A significant decrease in ascites and remission of clinical symptoms of abdominal distention and pain were observed after withdrawal of tacrolimus.CONCLUSION Tacrolimus-induced HSOS is a scarce but severe complication after liver transplantation. It lacks specific symptoms and diagnostic criteria. Timely diagnosis of HSOS is based on clinical symptoms, radiological and histological examinations. Discontinuation of tacrolimus is the only effective treatment. Transplantation physicians should be aware of this rare complication potentially induced by tacrolimus.

Key Words: Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome; Tacrolimus; Refractory ascites; Orthotopic liver transplantation; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS), previously known as hepatic veno-occlusive disease (HVOD), is a rare disorder characterized by painful hepatomegaly, ascites, weight gain and jaundice[1]. The initial lesion of HSOS originated from the injury of hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells, followed by the migration of damaged sinusoidal endothelial cells to the centrilobular veins, thus contributing to progressive fibrocystic occlusion of centrilobular veins and congestion of hepatic sinusoidal veins, and finally leads to intrahepatic post sinusoidal portal hypertension[2].

The diagnosis of HSOS is relatively difficult owing to the lack of specific symptoms. Although ascites, painful hepatomegaly and jaundice are identified as the most typical symptoms of HSOS, the clinical presentations are variable, from few symptoms to multi-organ failure and even death[3]. At present, the clinical suspicion of HSOS is based on the Baltimore and modified Seattle criteria which was actually formed for the diagnosis of HSOS in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) recipients[4]. In addition, no diagnostic criteria are available for HSOS after liver transplantation. Doppler ultrasound examination can present some non-specific signs of HSOS, including ascites, hepatomegaly and attenuated hepatic veins[5]. Moreover, enhanced computed tomography (CT) can further confirm the ultrasound findings. A flow obstruction is suspected if it shows patchy enhancement of the liver with unclear hepatic veins on the portal vein phase and delayed phase[6]. Additionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can monitor similar signs[7]. It also needs to exclude other diseases, such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, acute rejection, ischemic liver injury and biliary stricture. So, liver biopsy is recommended as the gold standard for the diagnosis of HSOS[8].

State of the art

In general, the frequencies of HSOS are associated with large amounts of toxins or drugs during chemotherapies, immuno-suppressive therapies and irradiation. It was reported that the main causes of HSOS were highly related with high-dose chemotherapy regimens and irradiation in HSCT recipients, as well as in liver, lung, renal and pancreatic transplantation recipients in Western countries[2]. In contrast, HSOS is most frequently associated with oral intake of Chinese herbal medicines that contain pyrrolidine alkaloids in China[8]. As reported, the morbidity of HSOS after liver transplantation was rare, only ranging from 1.9% to 2.3%[9]. However, although rare, the mortality rate of severe HSOS is more than 90%[4].

For liver transplantation recipients, azathioprine and acute rejection were thought to be two main causes of HSOS[10]. Recently, several studies have reported that tacrolimus could cause HSOS and discontinuation of the drug may be the only effective treatment[5,10,11]. In this study, we present 3 cases of HSOS related to tacrolimus after orthotopic liver transplantation. Among them, only one patient experienced acute rejection. All patients underwent orthotopic liver transplantation for hepatitis B virus (HBV)-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were applied as the initial immunosuppressive therapy. Acute rejection occurred in one patient and was relieved after the application of corticosteroid. Also, the immunosuppressive treatments were converted to sirolimus after the diagnosis of HSOS. Eventually, two patients achieved clinical remission after the discontinuation of tacrolimus, while one patient died of gastrointestinal bleeding and acute renal failure. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to present the dynamic course with clinical manifestation, radiological, pathological features and treatment for HSOS after liver transplantation.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Case 1:A 43-year-old man was hospitalized on POD (post-operative day) 14 after liver transplantation with chief complaints of abdominal pain and distension accompanied by poor appetite for 2 d.

Case 2:A 56-year-old man was readmitted on POD 50 after liver transplantation with chief complaints of fatigue and abdominal distension, accompanied by chest stuffiness for 10 d.

Case 3:A 57-year-old man went to the doctor with the chief complaints of abdominal pain and distention, accompanied by 850 mL of ascites and was hospitalized on POD 14 after liver transplantation.

History of present illness

Case 1:The patient described that abdominal pain and distension occurred 2 d ago. These symptoms were particularly severe in the upper abdomen. Although diuretics were administrated, abdominal distention was not relieved and renal function deteriorated. He also suffered from poor appetite and hypourocrinia.

Case 2:The patient suffered from abdominal distension and paroxysmal upper abdominal pain without any obvious inducement 10 d ago, accompanied by chest stuffiness and oliguria. Although diuretics were applied, the symptoms did not relieve significantly.

Case 3:The patient described that abdominal pain and distention occurred on postoperative day (POD) 14 after liver transplantation and this was accompanied by 850 mL of ascites. Diuretics were administrated but showed ineffective. The amount of ascites continued to increase, which peaked at 1050 mL on POD 16.

History of past illness

Case 1:The patient had a history of hepatitis B virus infection for more than 20 years and was diagnosed with HCC (BCLC stage A) at a local hospital about 8 mo ago. After the diagnosis of HCC, he received two radiofrequency ablations and one transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. However, the tumor was not completely necrotic and parts of it remained viable. At last, the patient underwent orthotopic liver transplantation. No specific pathology was observed in the graft liver at the time of transplantation. It took about 8 h for the operation, which was performed successfully with the satisfactory reconstruction of the vessels and biliary duct. The donated liver worked well after transplantation and the early recovery post-operative period was uneventful. The liver function and coagulation returned to normal 1 wk after transplantation. The portal venous phase of contrastenhanced CT on POD 10 showed the blood flow of hepatic veins were fluent. No stenosis was observed at the vascular anastomosis of hepatic veins or the suprahepatic inferior vena cava (Figure 1). The patient was discharged 12 d after transplantation and administered a routine immunosuppressive treatment consisting of tacrolimus (1.5 mg, twice daily) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).

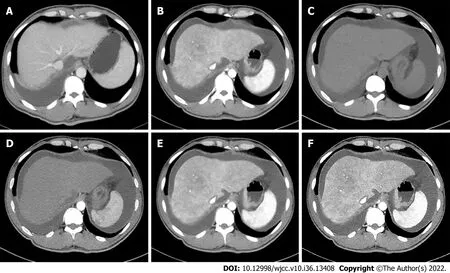

Figure 1 Typical abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography features of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome after liver transplantation. A: Portal venous phase computed tomography (CT) on postoperative day (POD) 10 showed the blood flow of hepatic veins were fluent. No stenosis was observed at the vascular anastomosis of hepatic veins and suprahepatic inferior vena cava; B: Portal venous phase CT on POD 14 showed hepatic veins were obscured, while no stenosis was observed at the vascular anastomosis of suprahepatic inferior vena; C, D: Plain scan and arterial phases CT on POD 14 showed that liver parenchyma was heterogeneous low-density; E, F: Portal venous phase CT on POD 14 showed enlarged liver with patchy enhancement, massive ascites and unclear hepatic veins and these signs existed persistently to delayed phase.

Case 2:The patient was a hepatitis B virus carrier for more than 20 years and took entecavir regularly. He received orthotopic liver transplantation for HBV-related HCC 1.5 mo ago. The operation was successful and early recovery after transplantation was smooth. The liver function and coagulation function returned to normal 10 d after liver transplantation. The patient was discharged on POD 14 following liver transplantation.

Case 3:The patient had a history of hepatitis B virus infection for 10 years. He was diagnosed with HCC 2 mo ago and received transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy. But the tumor was not completely necrotic. At last, he underwent orthotopic liver transplantation for small HCC. The operation was successfully performed and the early recovery after transplantation was stable. Liver function returned to normal 1 wk after transplantation while it showed a little fluctuation on POD 8. It was suspected that the patient suffered from acute rejection after liver transplantation. So, methylprednisolone was applied to enhance anti-immune rejection and the liver function soon returned to normal.

Personal and family history

Case 1:The patient had a history of hepatitis B virus infection for more than 20 years. There were no other special findings in his personal and family history.

Case 2:There were no other special findings in his personal and family history except for a history of hepatitis B virus.

Case 3:The patient had a history of hepatitis B virus infection for 10 years. There were no other special findings in his personal and family history.

Physical examination

Case 1:Physical examination revealed hepatomegaly and positive shifting dullness of the abdomen.

Case 2:Physical examination showed positive shifting dullness of the abdomen.

Case 3:Physical examination showed no positive signs.

Laboratory examinations

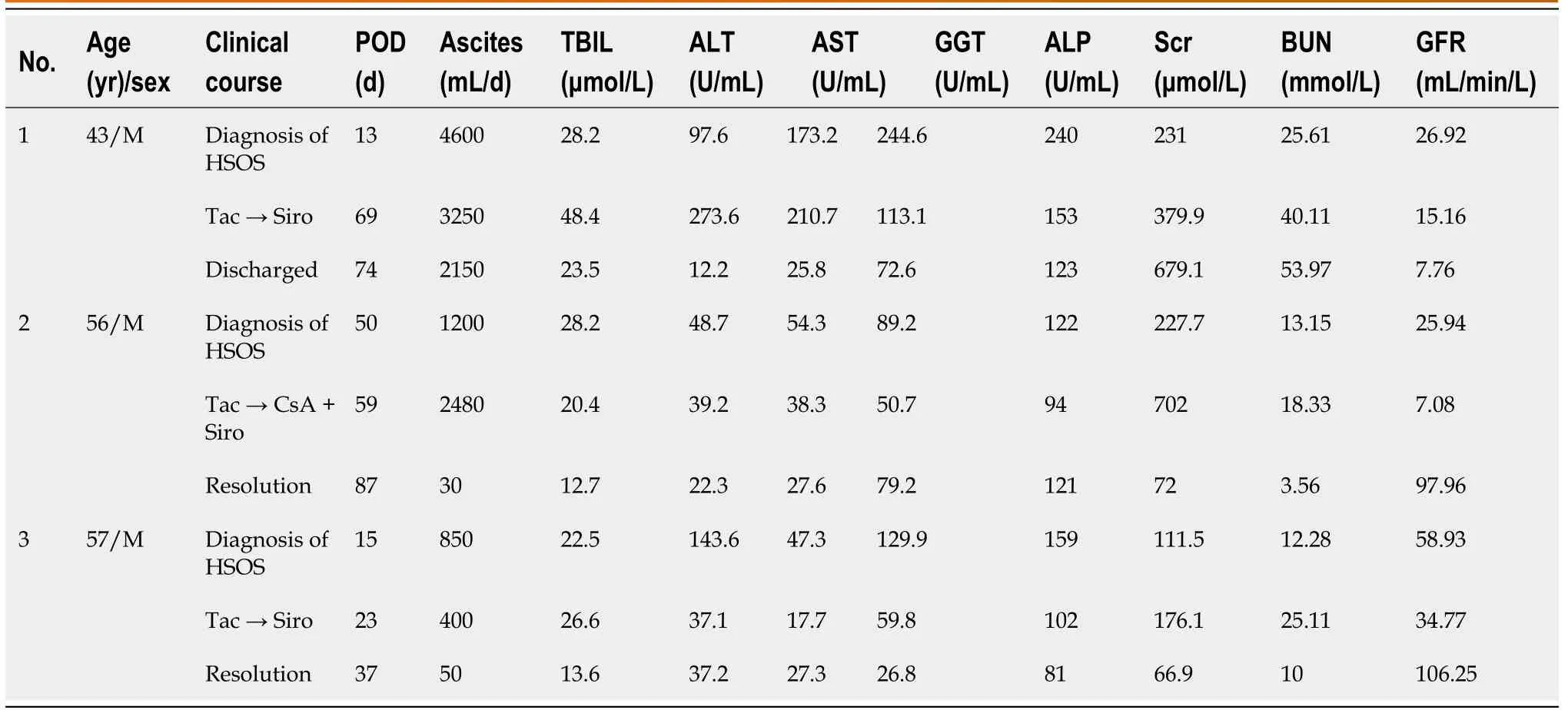

Case 1:Laboratory examinations showed a mildly abnormal liver function, severe renal insufficiency and hyperkalemia. Tests of viral infection of hepatitis A, B, C, D, E as well as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus were all negative and the serum trough concentration of tacrolimus was 8.0 ng/mL. The clinical characteristics during the disease were shown in Table 1.

Case 2:Laboratory examinations showed liver function was a little increased, but renal function had continuously deteriorated. Blood routine examination was normal. Virus infections such as hepatitis A, B, C, D, E as well as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus were all negative. The serum trough concentration of tacrolimus was higher than 30 ng/mL. The patient presented with 1200 mL of ascites drainage when admitted and it peaked at 2480 mL on POD 59. The clinical characteristics during the disease were shown in Table 1.

Case 3:Laboratory examinations revealed a mild elevation of total bilirubin, aminotransferase and the biliary enzyme spectrum. Virus infections such as hepatitis A, B, C, D, E as well as cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus were negative while renal function got worse and worse. The minimal serum concentration of tacrolimus was 6.9 ng/mL. The clinical characteristics during the disease were shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of three presented cases during the disease course

Imaging examinations

Case 1:Ultrasonography demonstrated that more than 2000 mL of ascites and an enlarged liver were present. Abdominal enhanced CT showed an enlarged liver with patchy enhancement and unclear hepatic veins with massive ascites (Figure 1).

Case 2:Ultrasonography showed large amount of ascites and an enlarged liver. Enhanced CT on POD 57 showed the liver with patchy enhancement, indistinct hepatic veins, massive ascites and pleural effusion at the phases of portal vein and a delayed period (Figure 2).

Case 3:Ultrasonography revealed an enlarged liver with moderate ascites and reflux of the left portal vein. Enhanced abdominal CT showed an enlarged liver with patchy enhancement and moderate ascites.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Case 1

All these findings supported the diagnosis of a tacrolimus-related HSOS by excluding the possibilities of viral infection, chylous fistula, tumor recurrence or acute rejection.

Case 2

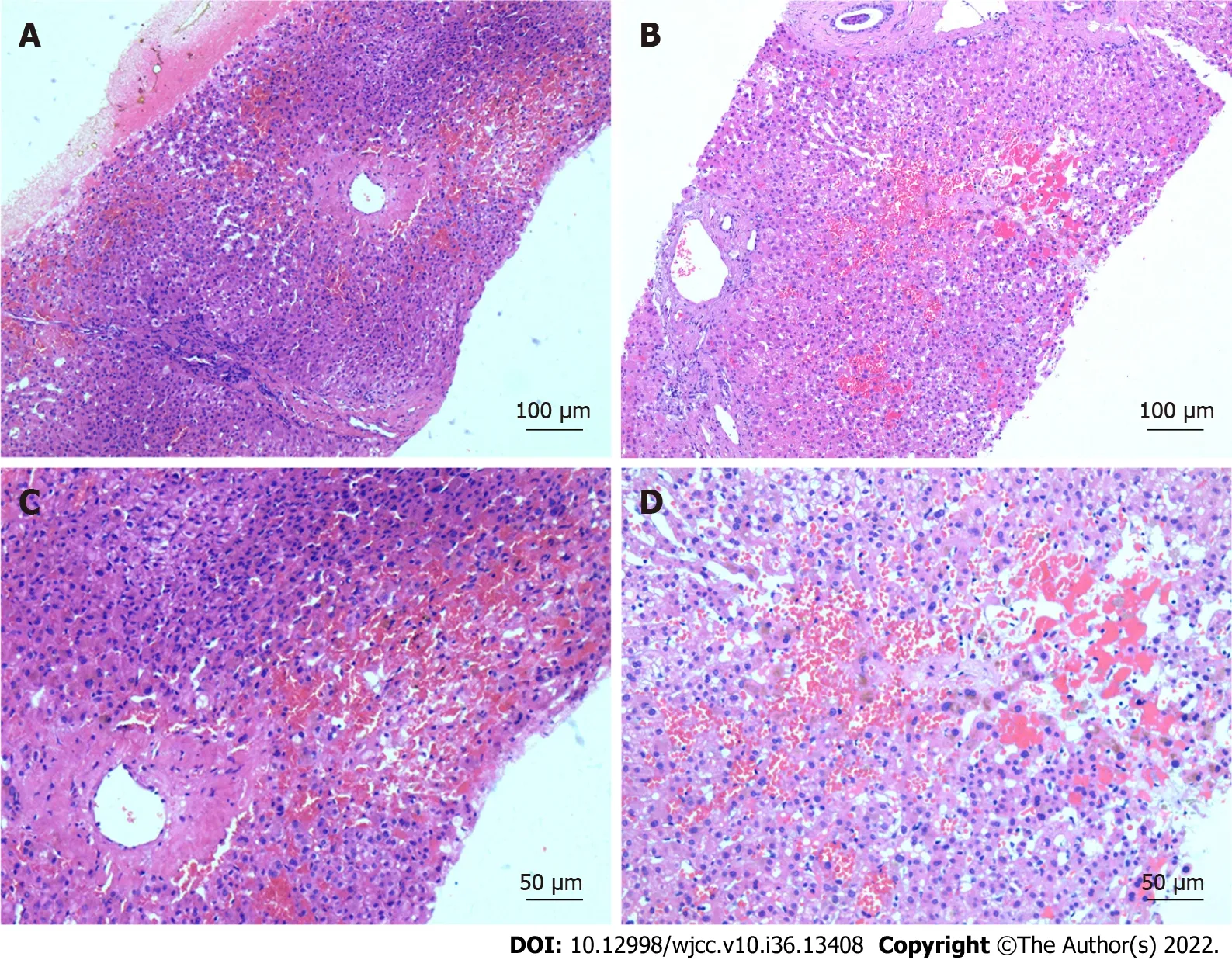

The patient was suspected of HSOS as acute rejection and viral infections were excluded. Liver biopsy was performed on POD 59 and the results showed hepatocyte edema, dilatation and congestion of hepatic sinusoidal with the formation of a local thrombosis (Figure 3). These results were in favor of the diagnosis of tacrolimus-related HSOS.

Case 3

The patient was suspected of HSOS based on the clinical symptoms and radiological examinations. To confirm the diagnosis of HSOS, he received a liver biopsy. The liver biopsy demonstrated dilatation and congestion of the hepatic sinusoidal with focal moderate edema of hepatocytes, enlarged portal area, lymphocytic infiltration, and venous endocarditis (Figure 3). The patient was finally diagnosed with HSOS by excluding acute rejection, obstruction of outflow, viral infection and biliary complications.

TREATMENT

Case 1

Although diuretics were administrated on admission, abdominal distention was not relieved and the renal function deteriorated. Ascites and pleural effusion were drained to alleviate the symptoms. The serum trough concentration of tacrolimus was 9 ng/mL on POD 20. Upon the diagnosis of HSOS, tacrolimus was switched to sirolimus with MMF being continued and enoxaparin was applied to improve the congestion of small hepatic veins.

Case 2

Diuretics were applied but proved to be ineffective. Ascites and pleural effusion were drained to relieve the symptoms of abdominal distention. The patient was finally diagnosed with HSOS, tacrolimus was replaced by sirolimus, and enoxaparin was used for antithrombotic therapy.

Case 3

At first, it was suspected that the patient suffered from acute rejection after liver transplantation. So, methylprednisolone was applied to enhance anti-immune rejection, and liver function soon returned to normal after that. Diuretics were also applied to relieve the clinical symptoms. But the amount of ascites continued to increase where diuretics were ineffective, which peaked at 1050 mL on POD 16. As tacrolimus was thought to be the most predisposing factor for HSOS. Upon the diagnosis of HSOS, tacrolimus was replaced by a sirolimus-based regimen and the MMF continued.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1

After the adjustment of immunosuppressant, the amount of ascites reduced and the symptoms were alleviated but then deteriorated from an upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The patient ultimately died of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and acute renal failure.

Case 2

As tacrolimus was replaced by sirolimus, the amount of ascites and plural effusion was significantly reduced and the symptoms of abdominal distention were also relieved after these treatments. After liver and renal function returned to normal, the patient was discharged on POD 87. Two months later, the abdomen enhanced CT showed normal morphology of liver, homogenous enhancement and clear hepatic veins without ascites (Figure 2). And the patient remained asymptomatic during the last followup.

Figure 3 Typical pathological features of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome after liver transplantation. A and C: Histopathologic examination of Case 2 showed congestion of hepatic sinusoids, fibrosis of centrilobular veins and edema in portal areas; B and D: Histopathologic examination of Case 3 showed significant dilation and congestion of sinusoids, regional hepatocytes necrosis, infiltration of red blood cells in the space of Disse, and fibroplasias in the portal areas (A, B magnification, × 100; C, D magnification, × 200).

Case 3

The levels of liver enzymes and total bilirubin decreased continuously and returned to normal after discontinuation of tacrolimus. The ascites reduced to 50 mL on POD 34. The liver function and renal function recovered to normal. The patient was discharged on POD 36 and remained asymptomatic on immuno-suppressive treatment of sirolimus and MMF in the last follow-up.

DISCUSSION

HSOS is a rare complication after liver transplantation, which ranges from 1.9% to 2.3% according to the literature[9,10]. Although the incidences are quite low, HSOS can cause graft failure and even death in liver transplant recipients[2]. So, it’s of great importance to recognize the clinical characteristics of HSOS in liver transplantation recipients. HSOS is associated with injury of hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells, which might be induced by many toxic agents, such as chemotherapeutic drugs, immunosuppressants, and Chinese herbal medicines containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids[1,8]. Azathioprine and acute rejection are considered as two main predisposing factors to induce HSOS after liver transplantation. In fact, azathioprine is rarely used nowadays due to its vascular hepatotoxicity. Although the incidences of acute rejection decreased due to the applications of new immunosuppressants, the morbidity of HSOS after liver transplantation remained unimproved. Therefore, we reviewed the literature on HSOS after liver transplantation[5,9-14], and recent progress in the early diagnosis and treatment of HSOS after liver transplantation were presented in Table 2. Several recent studies showed that tacrolimus was the most possible predisposing factor to induce HSOS and withdrawal of the drug may be the only effective treatment. Recently, some research also reported tacrolimus-related HSOS in renal, pancreas and lung transplantations[5,15-17]. However, the mechanism of tacrolimus-related HSOS still remains unclear. One possible explanation is that the genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 and glutathione-Stransferase influence the metabolism of tacrolimus, thus resulting in hepatoxicity[2,18]. In this study, we describe 3 patients suffering from HSOS after liver transplantation, among which one experienced acute rejection. Two patients were relieved of symptoms after switching from tacrolimus to sirolimus, indicating that tacrolimus might be the most relevant predisposing factor. However, this study was a single center retrospective case report and the sample size was small. The evidence may not be convincing. In the future, multicenter large sample retrospective case-control studies and randomized controlled studies are needed to verify these results.

Table 2 Literature review of recent progresses in the diagnosis and treatment of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome after liver transplantations

Although the typical symptoms of HSOS are painful hepatomegaly, ascites and jaundice, the clinical manifestations of HSOS after liver transplantation are not specific. Thus, early diagnosis of HSOS is difficult, which may lead to a missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. Besides, pathology is the gold standard for diagnosing HSOS and liver biopsy is difficult to achieve in most patients because of various reasons, such as severe coagulation disorders, massive ascites, patient refusal of an invasive examination and so on. It was reported that reversed blood flow in the branch of the portal vein may be the positive sign of HSOS[19]. In fact, we found reversed blood flow in the left branch of the portal vein and an ultimately formed thrombus in Case 3. Some studies analyzed the radiologic characteristics of HSOS and they found that an enlarged liver with patchy enhancement, massive ascites and pleural effusion accompanied by slender hepatic veins due to congestion of sinusoidal were the common features of abdominal enhanced CT and MRI of HSOS. The patchy enhancement of liver on abdominal enhanced CT and MRI is rarely presented in other liver diseases[6,7]. Therefore, the radiologic features are of great value in the diagnosis of HSOS and the extent of liver patchy enhancement might be highly associated with the prognosis of HSOS.

In fact, it still lacks an evidence-based treatment for HSOS after liver transplantation at present. Though defibrotide was recommended for HSOS treatment after HSCT, it was proven ineffective on patients with HSOS after liver transplantation[8]. All three patients in our study were not exposed to azathioprine or other hepatoxicity drugs except tacrolimus and tacrolimus was recognized as the potentially offending drug, so it was discontinued thereafter .The immunosuppressant therapy was replaced by sirolimus, where mycophenolate mofetil was continued. A significant decrease in ascites and remission of clinical symptoms of abdominal distention and pain were achieved following the discontinuation of tacrolimus, which further verified the suspicion that HSOS was triggered by tacrolimus. Although we and other researchers speculated tacrolimus may be the most possible predisposing factor for inducing HSOS after liver transplantation, the mechanism remains unclear. Further basic studies are needed to clarify the underlying mechanism.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we present three cases of HSOS after liver transplantation. The diagnosis of HSOS was first based on the typical symptoms including ascites, painful hepatomegaly and jaundice. Furthermore, the features of patchy enhancement on portal vein and delayed phase of abdominal enhanced CT were suspected of HSOS and ultimately confirmed by liver biopsy in two patients. Clinical and radiologic remissions were observed after withdrawal of tacrolimus. Transplantation physicians should be aware of this rare complication that might be caused by tacrolimus.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Feng Wu for histological examinations of the liver lesions, Cheng-Cheng Zhang for support in the diagnosis of HSOS, Wei Liu for assessment the conditions of liver transplantation recipients.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Jiang JY designed the study and wrote the manuscript; Jiang JY and Fu Y collected and analyzed the clinical data; Ou YJ and Zhang LD guided the diagnosis and treatment of HSOS; and all authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Supported bySurface Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81972760; The Joint Project of Chongqing Health Commission and Science and Technology Bureau, No. 2022QNXM020; Doctoral Through Train Scientific Research Project of Chongqing, No. CSTB2022BSXM-JCX0004.

Informed consent statement:The study performed followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for ethical approval was approved by the Ethics Committee of Southwest Hospital, Third Military Medical University (Army Medical University). Written informed consents were obtained from the three patients or their guardians for the publication of this report and the clinical data. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Jia-Yun Jiang 0000-0002-0802-5750; Yu Fu 0000-0002-8960-5000; Yan-Jiao Ou 0000-0001-7899-2415; Lei-Da Zhang 0000-0002-2357-5566.

S-Editor:Wang JL

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Wang JL

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年36期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年36期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Liver injury in COVID-19: Holds ferritinophagy-mediated ferroptosis accountable

- Amebic liver abscess by Entamoeba histolytica

- Living with liver disease in the era of COVID-19-the impact of the epidemic and the threat to high-risk populations

- Cortical bone trajectory screws in the treatment of lumbar degenerative disc disease in patients with osteoporosis

- Probiotics for preventing gestational diabetes in overweight or obese pregnant women: A review

- Effectiveness of microwave endometrial ablation combined with hysteroscopic transcervical resection in treating submucous uterine myomas