Pregnancy-induced leukocytosis: A case report

Xi Wang, Yang-Yang Zhang, Yang Xu

Xi Wang, Yang-Yang Zhang, Yang Xu, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Pregnancy is a complex physiological process. Physiological leukocytosis occurs often and is mainly associated with increased neutrophil counts, especially in the third trimester of pregnancy. Non-congenital leukocytosis with white blood cell counts above 20 × 109/L lasting 13 wk during pregnancy is rare and has been reported occasionally. Herein, we present a case of pregnancy-induced leukocytosis.CASE SUMMARY We present the case of a 33-year-old Chinese woman at 27 wk of gestation who had a leukocytosis complication. No abnormalities were detected in the examinations before pregnancy or in the first trimester. From the third trimester of pregnancy, the patient began to suffer from asymptomatic leukocytosis. We administered antibiotics to treat the patient; however, the complication persisted until the patient underwent a cesarean section after 40+3 wk of gestation. One day after the cesarean section, the patient’s neutrophil count returned to normal. After 2 years of follow-up, we found that the patient and baby were healthy.CONCLUSION Pregnancy-induced leukocytosis seems to be associated with immunoregulation and pregnancy termination may be the most effective treatment approach for pregnancies complicated with malignant leukocytosis.

Key Words: Leukocytosis; Pregnancy; In vitro fertilization; Malignancy; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy is a complex physiological process[1]. The normal range of white blood cell (WBC) counts changes with age and pregnancy[2,3]. In pregnant women, local adaptation of the maternal immune system enables the successful coexistence of the mother and fetus/placenta[4]. Physiological leukocytosis (3.5-9.5 × 109/L) has a high incidence and is mainly associated with the increased circulation of neutrophils (1.8-6.3 × 109/L), especially during the last trimester of pregnancy[5]. It is important for clinicians to distinguish between malignant and non-malignant causes and to identify the most common causes of non-malignant leukocytosis. During pregnancy, the normal WBC count increases gradually (third trimester 95% upper limit = 13.2 × 109/L; 99% upper limit = 15.9 × 109/L)[6]. Leukocytosis is similar in several non-obstetrical cases, such as infections, allergic reactions, malignancies, surgery[7], traumas[8], and strenuous physical activities[9]. For pregnant and parturient women, an increased WBC count may also be related to gestational and puerperal infections such as endometritis[10] and chorioamnionitis[11]. Other factors that affect WBC count include smoking[12], race[13,14], and body mass index[14]. Leukocytosis is a common symptom of infections, especially bacterial infections, and physicians should be encouraged to recognize other signs and symptoms of infections. Chorioamnionitis, defined as the inflammation of fetal membranes after 20 wk of gestation is one of the main causes of perinatal morbidity and mortality[15]. The traditional diagnostic criteria for clinical chorioamnionitis are fever and at least two of the following: Maternal tachycardia, maternal leukocytosis (maternal WBC > 15000 in the absence of corticosteroids), uterine tenderness, fetal tachycardia (> 160 bpm for 10 min or longer), and foul-smelling amniotic fluid[16,17].

Non-congenital leukocytosis with WBC counts above 20 × 109/L for 13 wk during pregnancy is rare and has been reported occasionally. Herein, we present the case of gestation-induced leukocytosis.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a complaint of high blood pressure for 6 wk and leukocytosis for 13 wk.

History of present illness

The patient had experienced leukocytosis for 13 wk at the time she presented to the emergency department. To prevent implantation failure after IVF, she took aspirin enteric-coated tablets 75 mg a day, 5 mg acetate orally once a day, and one vitamin complex tablet a day until 12 wk of gestation. During her pregnancy, repeated routine blood tests before 20 wk of gestation showed that the WBC and neutrophil counts were within the normal range. Ultrasonography suggested a post-placental hematoma with a diameter of approximately 20-30 mm before 20 wk of gestation, which disappeared thereafter. At 27 wk of gestation, the WBC rose to 23.73 × 109/L and the neutrophil count rose to 20.74 × 109/L (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Variation tendency of leukocyte and neutrophil. Line chart is shown depicting changes in white blood cell and neutrophil count over time. N:Neutrophil count; WBC: White blood cell count.

History of past illness

The patient was diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome and her partner was diagnosed with male factor infertility. The patient had no known allergies to food or medication. In addition, she denied any family history or history of sexually transmitted infections. The patient was an employee of an Internet company, did not smoke and was not exposed to second-hand smoking during pregnancy.

Personal and family history

The patient had no specific personal and family history.

Physical examination

At the initial inspection, the patient had a blood pressure of 126/87 mmHg and a pulse rate of 68 beatsperminute. The patient’s lungs were clear and she had normal heart sounds with no murmurs on auscultation.

Laboratory examinations

At 27 wk of gestation, blood analysis revealed leukocytosis of 23.73 × 109/L, with predominantly neutrophils (87.4%) with normal hematocrit and platelet count, and the neutrophil count rose to 20.74 × 109/L (Figure 1). C-reactive protein count was 0.52 (< 0.8) mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 30 (0-20) mm/h, and procalcitonin (PCT) count was < 0.05 (< 0.5) ng/mL, which showed no sign of infection.

Methods

The manuscript is a case report and meets the requirements of biostatistics.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the case is asymptomatic leukocytosis.

TREATMENT

The patient had no fever, and had a normal temperature. In addition, there was no presence of other symptoms, including no cough, expectoration, oral ulcers, or shivering. She was administered antibiotic treatment for 2 wk, which did not work. Afterward, the patient visited several other hospitals; during this time, routine blood tests showed a sustained high level of WBC and neutrophil counts. The patient visited the outpatient department of our institution because of leukocytosis. The C-reactive protein count was 0.52 mg/dL, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 30 mm/h, and the PCT count was < 0.05 ng/mL, which showed no sign of infection. Thereafter, the patient visited the outpatient hematology department. The patient refused a bone marrow biopsy. Peripheral blood smear showed that mature neutrophils accounted for 73.2%, and the count of immature granulocytes was 0.95 × 109/L, accounting for 3.7%. Tests at another hospital showed leukocytosis, but normal levels of red blood cells and megakaryocytes. The patient was hospitalized with an elevated blood pressure at 40+3wk of gestation. On admission, the WBC count was 20.09 × 109/L, the neutrophil granulocyte count was 15.3 × 109/L, the blood platelet count was 343 × 109/L, and the hemoglobin concentration was 140 g/L. The next day, she underwent a cesarean section because of fetal distress. The surgery was successful.

On the first postoperative day, the WBC count was 14.71 × 109/L, the neutrophil granulocyte count was 11.26 × 109/L, the hemoglobin concentration was 124 g/L, and the platelet count was 304 × 109/L. The thyroid function tests were within the normal range; free thyroxine was 16.27 pmol/L and thyrotropin was 1.16 uIU/mL. Ultrasonography of the fetus, abdomen, lower limb arteries, and deep veins showed that all the tested areas were normal. Ultrasonography of the kidneys showed a right hydronephrosis with a renal pelvis approximately 1.1 cm wide. Tests for immunoglobulin M (IgM) against toxoplasma, IgM against rubella virus, and IgM against cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex type I virus, and herpes simplex type II virus were negative. Tests for hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, andTreponema pallidumwere all negative. By 34 wk, blood pressure had risen to a range of 138/80 mmHg and 142/90 mmHg, and the patient was diagnosed with pregnancy-induced suspicious hypertension without medication. During 40+3wk of gestation, she underwent a cesarean section because her blood pressure had increased to 143/90 mmHg. Six weeks postpartum, the patient’s blood pressure gradually returned to normal.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Postoperatively, neutrophil granulocytes returned to normal levels. The patient delivered a live, healthy, full-term babyviaa cesarean section. After 2 years of follow-up, the patient and baby were found to be healthy.

DISCUSSION

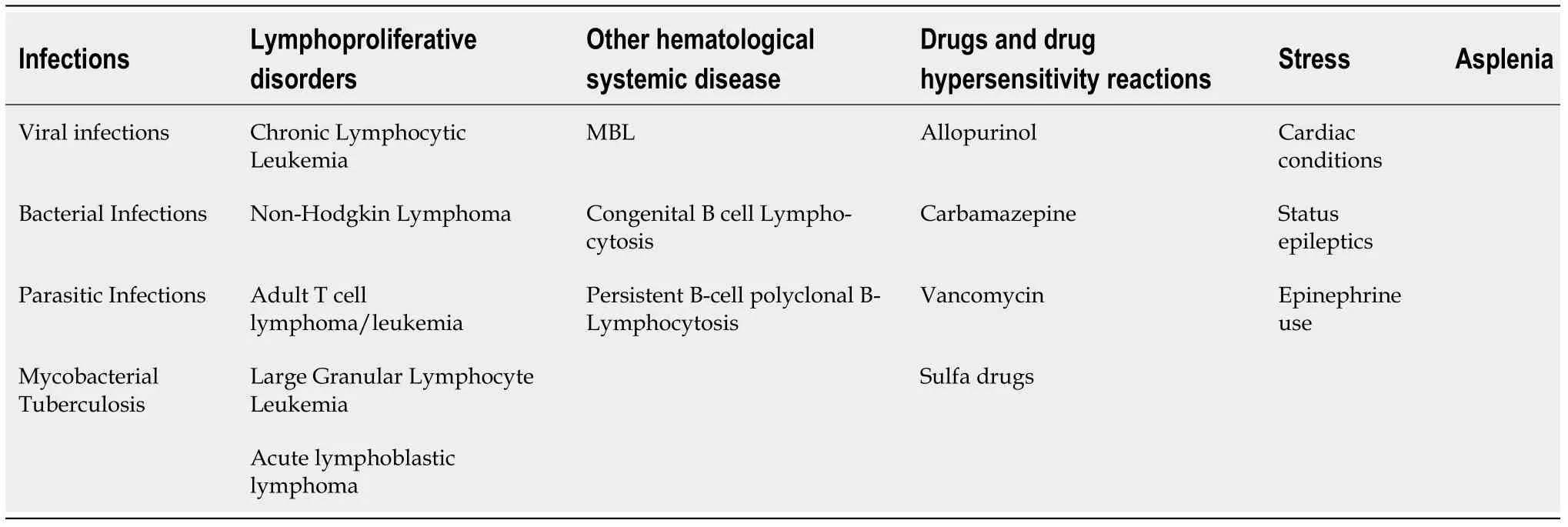

Hematological diseases in pregnancy should be meticulously managed with multidisciplinary cooperation, including obstetrics and hematology. Distinguishing between reactive and malignant lymphocytosis is challenging and may vary with age and other demographics. Table 1 lists the most common etiologies[18]. The patient did not suffer from allergic reactions, malignancy, surgery, trauma, strenuous physical activity, or smoking; in addition, the patient had no fever, had normal temperature, experienced no other symptoms such as cough, expectoration, oral ulcers, or shivering. The patient visited the outpatient department for the complaint of an infection. The C-reactive protein count was 0.52 mg/dL, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 30 mm/h, and the PCT count was < 0.05 ng/mL, which showed no sign of infection. A peripheral blood smear showed that mature neutrophils accounted for 73.2%, and immature granulocytes count was 0.95 × 109/L, accounting for 3.7%. Tests at another hospital showed leukocytosis, but normal levels of red blood cells and megakaryocytes. Six weeks postpartum, the patient's blood pressure gradually returned to normal, which illustrated that it was not malignant. Molberget al[19] found that the average WBC count in a laboring patient was 12.45 × 109/L, with a range of 4.4 × 109/L to 29.1 × 109/L. WBC counts in patients with postpartum complications were similar to that in patients without complications (12.9 × 109/Lvs12.3 × 109/L,P= 0.449)[19]. We describe a case of asymptomatic leukocytosis with WBC counts > 20 × 109/L during pregnancy. The patient did not suffer from leukocytosis until 27 wk of gestation; after cesarean section, WBC and granulocyte counts dropped to normal levels. Levothyroxine sodium is safe for pregnant women, and there is no evidence that its side effects include leukocytosis[20]. At the same time, there was no obvious evidence that hypothyroidism caused leukocytosis, and the patient had no history of using cytotoxic drugs or other medications that explicitly cause leukocytosis. Therefore, we believe that drug-induced leukocytosis was less likely the case.

Table 1 Causes of leukocytosis

There are a few reports on leukocyte counts and differentials related to the severity of pregnancyinduced hypertension. Terroneet al[21] assessed the difference in leukocyte counts between normal pregnancies and pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia (PE). In a retrospective study of 240 women, women with severe PE had a significantly higher WBC count than those with mild PE and normal pregnancy controls [10.66 +/- 3.70vs9.47 +/- 2.59 and 8.55 +/- 1.93 (× 109/L) (P< 0.0001)]. The increase in the total WBC count was mainly due to an increase in the number of neutrophils [8.05 +/- 4.01 (severe)vs6.69 +/- 2.23 (mild) and 5.90 +/- 1.79 (controls) (× 109/L) (P< 0.0001)]. Terroneet al[21] evaluated the total WBC count of 86 patients with severe PE with and without hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome of 91 patients. The WBC counts in patients with HELLP syndrome (12.5 +/- 0.442 × 109/L) were significantly higher than those in patients with severe PE (10.3 +/- 0.288 × 109/L). The patient was diagnosed with hypertension during pregnancy, without PE. Furthermore, the counts of WBCs were above 20 × 109/L. Leukocytosis may have had nothing to do with hypertension in this case.

There have been few reports on the relationship between leukocytosis andin vitrofertilization and embryo transfer (IVF). Ludwiget al[22] observed the effects of a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone antagonist protocol (Cetrorelix) and the administration of recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) on the development of leukocytosis compared to the administration of urinary human menopausal gonadotropin. Thirty patients underwent IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment after controlled ovarian stimulation using a multiple dose protocol and the luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) antagonist Cetrorelix, and no significant leukocytosis was discovered after controlled ovarian stimulation using the LHRH antagonist Cetrorelix and recFSH.

During pregnancy, the integration and balance of these immune factors produce an environment that allows the fetus to escape rejection by the maternal immune system. Multiple mechanisms influence the maternal immune system in accepting semiallogeneic fetal tissues during pregnancy[23]. Female sex hormones affect many immune pathways more often during pregnancy.

Limitations

In summary, the etiology and mechanism of this phenomenon remain largely unknown. In addition, during pregnancy, asymptomatic leukocytosis seems to be related to immunosuppression induced by immunoregulation. The termination of pregnancy may be effective in pregnancies complicated with leukocytosis; however, further studies are needed to confirm this.

CONCLUSION

Thus, we conclude that leukocytosis seems to be associated with the pregnancy itself and is associated with immunoregulations. Although this study presents a case of leukocytosis without evidence of clinical infection, caution should be exercised when applying these data clinically. We suggest that pregnancy termination may be a therapeutic approach for pregnancies complicated with leukocytosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the patient in this study for her collaboration.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Wang X and Xu Y wrote the manuscript with contributions from all other authors; Zhang Y performed the topic selection, designed the study and edited the manuscript; All authors contributed to and reviewed the final manuscript.

Supported byScientific Research Seed Fund of Peking University First Hospital to Xi Wang, No. 2020SF30.

Informed consent statement:Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Xi Wang 0000-0002-2068-4740; Yang-Yang Zhang 0000-0001-7224-9954; Yang Xu 0000-0003-0035-4186.

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Fan JR

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年36期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年36期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Liver injury in COVID-19: Holds ferritinophagy-mediated ferroptosis accountable

- Amebic liver abscess by Entamoeba histolytica

- Living with liver disease in the era of COVID-19-the impact of the epidemic and the threat to high-risk populations

- Cortical bone trajectory screws in the treatment of lumbar degenerative disc disease in patients with osteoporosis

- Probiotics for preventing gestational diabetes in overweight or obese pregnant women: A review

- Effectiveness of microwave endometrial ablation combined with hysteroscopic transcervical resection in treating submucous uterine myomas