渔业在陆地上的印记——北极景观中的聚落结构与空间逻辑

著:(挪威)卡尔·奥托·埃利弗森 (挪威)艾斯彭·奥克鲁斯特·豪林 译:王威

安妮·惠斯顿·斯本(Anne Whiston Spirn)引入“深层结构”(deep structure)的概念来表示景观的持久稳定性:“景观中的所有有机体都与之回应。深层结构可以传达特定地点的基本气候、地貌和生物过程(信息)。这些过程跨越了漫长的时间尺度,在大区域和微观尺度上运行和相互作用,进而形成了深层结构。”深层结构由地域和地方的特征(包括全球地方化、地质和气候因素)塑造,这些因素“造就了具有鲜明的空间、物理和时间特征的景观结构”[1]。

深层结构代表资源,为生态系统、栖息地以及社会与环境进程奠定基础。用斯本的话来说:“(深层结构)响应了自然进程和变化的人类目的。”[1]人类与生态系统互动并改变环境,甚至有意识地构建系统,创造出查尔斯·L.雷德曼(Charles L. Redman)所定义的“社会生态系统”[2]。然而这些系统并不是稳定的。根据埃勒·C.埃利斯(Erle C. Ellis)的说法,社会文化生态位建设(socio-cultural niche construction)是一个持续的过程,人类根据自身需要改变着环境和生态系统[3]①。

在历史上,景观(相对于荒野)生产的逻辑与地方特定的竖向驱力直接相关,而全球生产链和市场使得地方景观受到本土和地域生态位之外的横向驱力的影响。应对(应对策略)的概念描述了社会是如何改变以开拓新的条件[4-5],它关注的是人们和社会如何创造更多的机会,或者更具体地说,是根据自身需求制定重要的策略,用亨利·列斐伏尔(Henri Lefevre)的一个术语来解释,就是根据自身需求进行“空间生产”(produce space)[6]。

当讨论社会、景观、建筑是如何相互关联的问题时,将建成环境视为社会物质(sociomaterial)的多层序列,呼应不同的历史结构不失为一个行之有效的方式。“在每一个社会物质层中,人们都可以观察到建成环境与物质生活互动的踪迹。周边事物既是生存方式的框架,也是生活文化的表达[7]。

1 深层结构

挪威西临北大西洋,北临巴伦支海,从坐落于李斯塔的南部灯塔到北部城市瓦尔达的距离为1 789 km[8]。挪威的海岸线崎岖,沿峡湾延伸,总长约100 915 km[9](图1),仅次于加拿大。北极圈(66°33′45″N,即极昼和极夜现象出现的理论边界)从距挪威最北端约800 km的萨尔特山脉横穿挪威。从地理角度而言,这意味着挪威北部的大部分地区属于北极或更准确地说是亚北极地区,是森林带与北方针叶林之间的过渡地带。然而,受到墨西哥湾暖流的影响,挪威沿海气候相当温和,只有在芬马克(挪威最北端的郡县)的东部半岛,出现类似于西伯利亚、阿拉斯加和加拿大北部的北极气候——位于66°33′N以北的无夏季带,7月平均气温低于10 ℃。

1 挪威海岸线,连接海洋和欧洲文脉Norway, coast, access to oceans and European context

北大西洋海岸的大部分地区山脉陡峭贫瘠,最高峰可达1 800 m。整个地区主要处在加里东山脉地质带,海洋通过峡湾和纵深的沟渠与陆地接壤。罗弗敦群岛、塞尼亚群岛和韦斯特隆群岛是鳕鱼渔业的核心区域,主要由坚硬的前寒武纪基岩构成,地貌种类多样,向海洋内部延伸。在芬马克郡,95%的土地在海拔500 m以下,沉积物向下渗透,将基岩覆盖,形成了一个没有树木、主要由苔藓和地衣组成的生物群落。沿峡湾和岛屿向南,是挪威语称作“滨海平地”的地方,即海岸线和山脉之间地势平坦的草木繁盛之地。

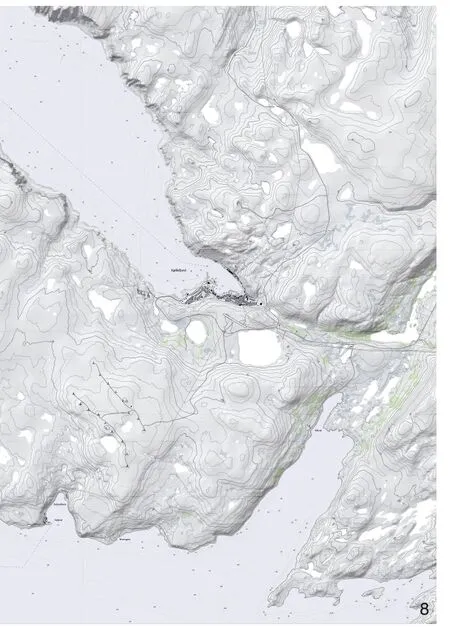

自古以来,在这片土地上,人们赖以生存的资源是海洋而非陆地。深水测量(bathymetry,图2)是深层结构的重要组成部分。连通着岛屿和峡湾的崎岖海岸造就了极其多样的水下地貌,2种不同的陆地系统对渔业和渔村的地方化具有决定性意义。一种是浅水区,从罗弗敦以南的瓦斯特弗约顿向北一直延伸到大西洋的底部(挪威海盆),这个深水边界叫作Egga。另一种是连续的浅水海岸,它沿着芬马克海岸延伸至巴伦支海的海底,具有适于渔业的特性。这2个系统是2种同类型海洋生态系统的基础。

2 挪威北部海岸的深水测量The bathymetry of the North Norwegian coast

2 资源

在国际市场中,如不依赖国家的补贴和优厚的区域政策,挪威北部薄弱的农业将无法存续。相反,大西洋北部沿海水域和巴伦支海的鱼类资源可能是世界上最丰饶的。根据对生产系统和聚落结构的历史影响而言,大西洋鳕鱼(挪威语:skrei)是生态系统中的初级资源②。不同于生活在峡湾和大西洋的普通沿海鳕鱼,大西洋鳕鱼一年中的大部分时间生活在北极和巴伦支海,每年冬季从巴伦支海向南迁徙,它们沿Egga,跟随富含营养的水流到达罗弗敦群岛以南、位于瓦斯特弗约顿的产卵地,成为1—4月的渔期资源。世界上大多数的鳕鱼捕捞业现在都已成为历史。曾经对葡萄牙人,以及后来对美国人和加拿大人都十分重要的纽芬兰渔业,因过度捕捞已不复存在。到目前为止,在斯瓦尔巴群岛和扬马延岛的渔业区和大的国家经济区中,挪威的渔业资源管理是相对成功的。受水深、墨西哥湾暖流的走向和纬度差异的影响,大西洋和巴伦支海的生态条件在远洋渔业(鲱鱼、鲭鱼、毛鳞鱼、沙鳗和其他群游鱼类)和底栖渔业(除了鳕鱼以外的大部分白鱼,以及黑线鳕和狭鳕的储备都是最丰富的)中都呈现差异(图3)。

3 挪威北部海岸鱼类资源。图上绿色区域表示鳕鱼的位置,颜色越深表示鳕鱼资源越丰富Fishing resources along the Northern Coast of Norway. The intensity of the green color shows the localization and abundance of the species Cod

滨海平地——围绕着峡湾的适于耕种的平坦区域,上面的沉积物成为农业、畜牧业和种植业的基础资源。这里的气候过于恶劣,不适合种植谷物和水果,因此在农场附近的菜地种植土豆、胡萝卜、卷心菜和一些浆果类作物,此外,未开垦的大地也可以被加以利用,萨米族人冬季在长有鹿蕊的内陆牧场放牧,夏季则迁移到沿海地区。陆地和海洋中的很多资源,例如水力、矿产、石油和天然气都已被人们利用,然而其中仍有许多潜在资源。

3 社会文化生态位建设

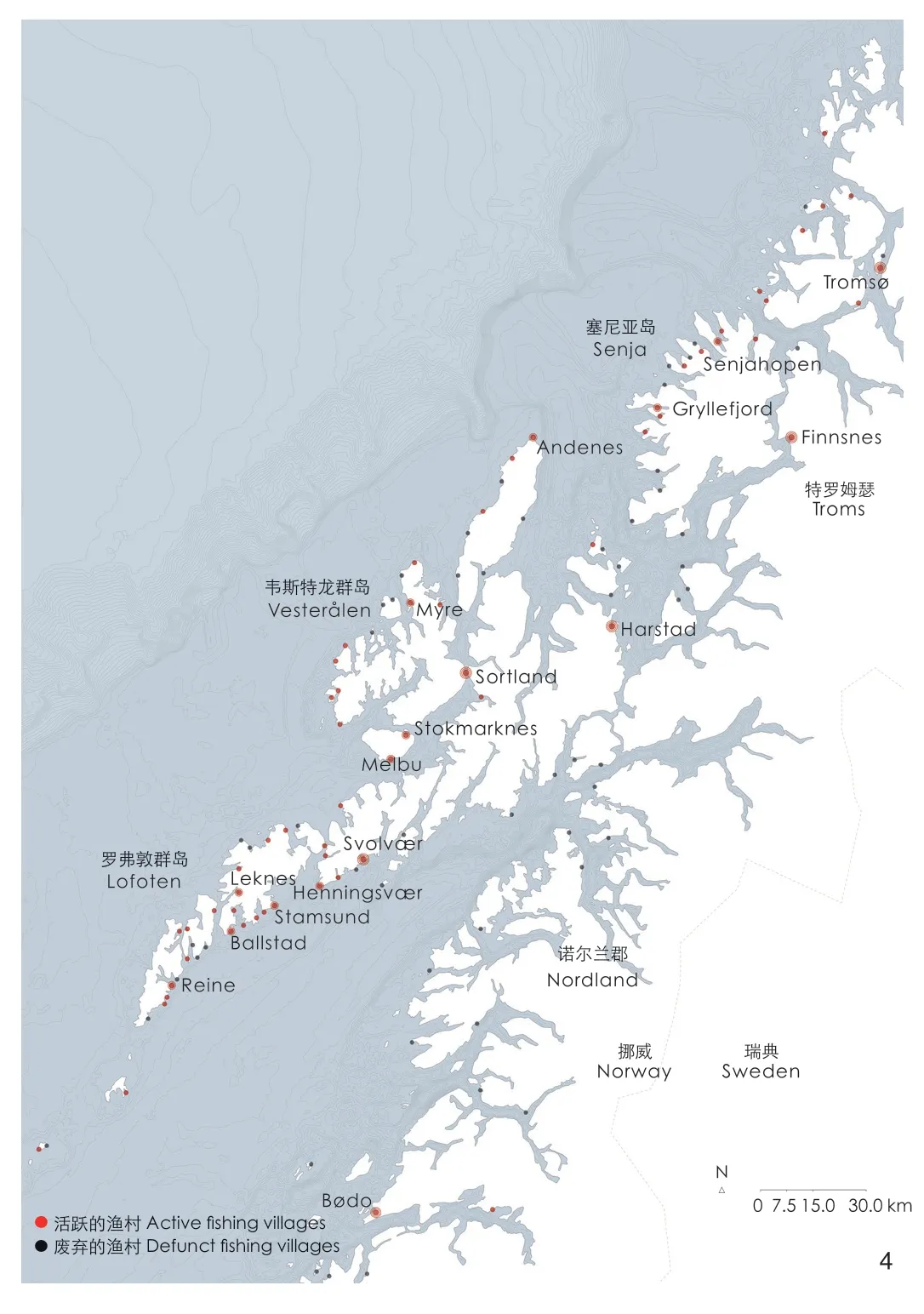

鳕鱼渔业的一个特点是生产过程具有较为持续的稳定性。在1 000年前,鳕鱼干是第一种可以在欧洲市场流通的挪威商品。它的生产模式非常简单,就是把除去内脏的鱼挂在架子上晾干。尤其受墨西哥湾暖流影响,岛屿的气候相对温暖,阳光充足且多风,(这为鳕鱼干的生成)营造了完美的风干环境,避免了霜冻和昆虫的侵扰。现代钢架保留了与传统木杆架类似的设计和技术,用于悬挂和晾晒鳕鱼。在专业和商业生活方面,城市化意味着专门化。在挪威北部海岸,这种专业化很早就发生了,因为鳕鱼干成为一种国际商品,这不仅创造了商业经济,也创造了渔村。这些渔村在某种程度上充当了专业化聚落的角色,专门为国际市场提供渔业产品(图4、5)。

4 地图显示了位于罗弗敦、韦斯特龙和塞尼亚岛渔村的位置点,这是大西洋鳕鱼渔业的核心区域Map showing the localization of fishing villages in Lofoten, Vesterålen and Senja,the core area for the skrei fisheries

人类活动的地域格局(聚落结构)形成的要素包括港口的质量、与渔场的距离、水对于渔场可能造成的危害、与可建土地的通达性和本地农业资源储备。土地利用是陆地和海洋之间的一场协作与竞争。在北欧乃至欧洲的贸易体系安全良好时,如中世纪晚期和19世纪后期的北欧工业化时期,渔村繁荣起来;当贸易线路变得不稳定,鱼价低廉,粮食难以购买时,人们就从渔村迁往峡湾,耕种土地,从事农业。

渔村不是一个明确的统计学或地理学术语。在渔村,渔民在港口有自己的泊位停放船只。渔获物的最初销售,即渔民与鱼商之间的首次交易,就在渔村里进行。当然,渔民不一定都居住在村中,他们可能是在港口捕鱼的季节性工人。历史上,挪威北部海岸的生存聚落经常被描述为小型个体农场的集合,依靠捕鱼带来收入。在农业资源丰富和容易捕鱼的地方,会形成密集的渔村,它们由许多个体农场和农舍组成。尽管整个沿海地区的渔业遵循着相对一致的模式和技术,但从地点、产权条件、生产方式和建造文化的角度来讲,每个地方又都与众不同。渔业和农业相结合形成了综合体农场(挪威语:kombinasjonsbruk),渔村代表着渔业在北方聚落形态上的印记。

历史上,不同类型的渔村可以基本区分为:1)永久定居的村庄,典型的就是由小农场组成的密集组团;2)季节性渔村,以流动性渔民的渔业为经济支撑(图5~9)。罗弗敦群岛的渔村位于天然港口,靠近渔场,有大量的季节性鳕鱼群经过。这些资源归本地主要的土地持有者和社区集体所有,他们拥有大型的白色住宅、晾鱼架、防洪堤边上的用于储存出口干鱼的棚屋,以及港口内的渔民小屋(这些小屋位于适合建造木质房屋的地点),渔业生产和权力关系都蕴含在渔村中。最古老的聚落应该是那些有农业资源的、永久定居的渔村。当中许多村子的历史都可以追溯到鳕鱼干首次成为交易商品的时代,从中世传承下来的沿海洋延伸到山脚的狭长的产权划分形式,依旧是今天村庄的基础格局。在19世纪末的土地整合过程中,挪威农村的农田经历了重新分配与合并,发展出更具备经济效率的农业单元,以应对不断增长的城市人口的需求。过程中,农舍搬迁和重新组合,原有村庄瓦解。然而渔村的合并并没有造成密集的农舍群落的解散和搬迁,因为渔业、船只和港口远远比农场更重要。渔业是一个联合性的企业,依靠海上辛勤劳作的人、经营农场和照料家庭的人之间通力协作,从而达成社群联结(图10)。

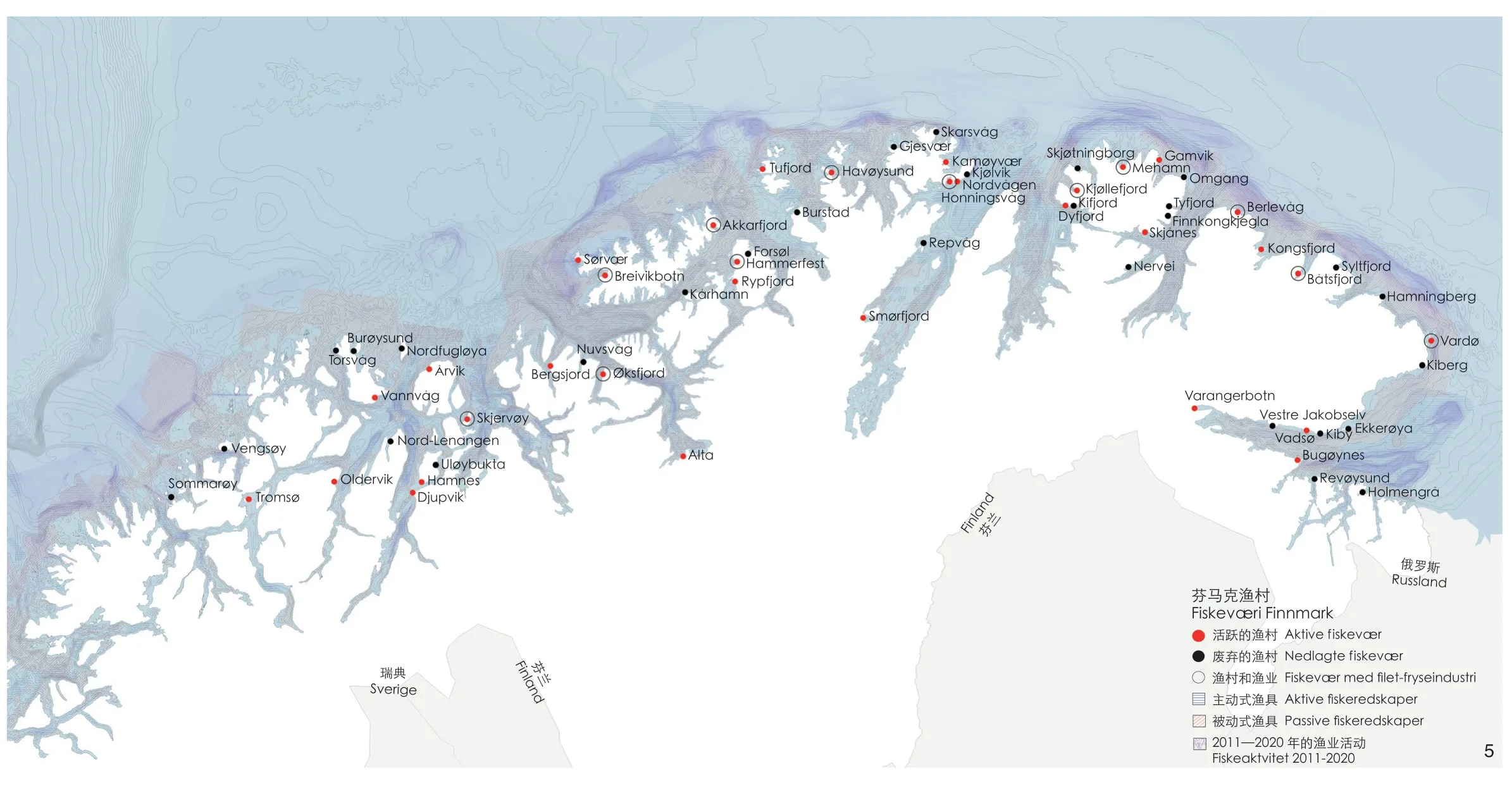

5 特罗姆瑟和芬马克的渔村,从塞尼亚岛到与俄罗斯的边境线。圆圈的附加标记表示的是在“二战”结束时撤退的德国军队烧毁芬马克后,由社会民主政府创立的渔业聚点。沿海捕鱼资源也标注在地图上Fishing villages in Troms and Finnmark, from the island Senja and to the border with Russia. The additional marking with a circle shows where fishing industries were first initiated by the social-democratic government after the retreating German troops burned down Finnmark at the end of the Second World War. Coastal fishing resources are also marked on the map

6 斯塔姆松——罗弗敦群岛西沃格岛的主要渔村和贸易运输中心之一Stamsund. One of the major fishing villages and center for trade and transport at Vestvågøy, Lofoten

7 诺德梅拉——位于韦斯特龙的安多岛的小渔村,显示着中世纪的土地划分结构。港口得到改善,渔业被设立在专门的位置Nordmela. Small fishing village at Andøya, Vesterålen,with the medieval plot-structure still showing. The harbor is improved and the fishing industries set on a pier

8 舍勒菲尤尔,诺德金哈尔夫霍伊——一个典型的芬马克渔村,位于峡湾内部朝北的封闭港口。几乎没有农业用地,只能进行驯鹿放牧,向南驱车2 h即可到达主要道路、机场、繁荣的渔场和渔业地区Kjøllefjord, Nordkinnhalvhøy. A typical Finnmark fishing village located in a shielded harbor in a fjord facing north.Nearly no agricultural land, only grazing for reindeer,2 hours driving south to reach the main roads, an airport,prospering fisheries and fishing industries

9 诺尔辰半岛的梅哈恩——地图展示着芬马克典型渔村的形态。工业区位于港口附近,一条连接整个区域的主干道,在西向坡地上规划的住宅区,中间穿插着用蓝色标记的小片草地Mehamn, Nordkinnhalvøya. Map showing the typical morphology of a fishing village in Finnmark. Industries around the harbor, a main road linking things together,planned areas for housing in the slopes facing west,small patches of grass-land marked in blue

10 货船“天线”号在迈尔港卸下了一批渔获的大西洋鳕鱼。在工业生产中,渔获物被清理并去掉内脏,其他所有部分都会被利用。几个小时内,鱼就会被放在冰上,装上拖车,向南部出口The vessel Arial unloads a catch of skrei in Myre harbor.The catch is gutted and cleaned in the industry; all parts of the fish are used. In a few hours the fish is put on ice,and exported southwards on trailers

沿着挪威大部分海岸,从西部的莫勒郡到最北部的芬马克郡,建立的定居形式——渔村,标示着社会文化生态位、栖息地和聚落形态。那些地方有的曾经荒芜,如今繁盛;有的已经变成城市,渔业部门变得次要。如今,罗弗敦、韦斯特龙、安多亚和塞尼亚大西洋鳕鱼的核心地区,以及芬马克海岸沿岸,渔村结构的现状最为稳定,那里的鱼类资源全年可享,集约型渔业在19世纪之前就已兴起。

4 社会物质层

调查渔村的历史、变化的景观、村庄的组织方式和建筑时,一系列叠加的“社会物质层”[10]会明确地显现出来。这一概念由社会理论家达哥·奥斯博格(Dag Østerberg)提出,用于表述城市建筑中的历史结构。在每个单独的社会物质层中,人们都可以追溯建成环境与这一物质领域中的活动之间的联系。这就是景观和建筑的原则,反映着它们作为生产和生活方式的工具而被创造出来的时代。这种理解方式类似于安德烈·科尔博斯(André Corboz)的概念,他认为土地是“复写本”(palimpsest),是对随时间推移而积累的不同景观层的系统解读[11]。理解方式也涉及结构主义理论,用历时(随着时间)和同时(现在)的科学研究诠释现象[12]。

在研究中,我们根据时间线区分出6个不同的社会物质层。1)历史层(historical layer,图11)反映和显现于村庄的本地化、土地使用和建筑物的组织原则,以及木质建筑的建造原理之中。这些建筑的原材料来源于从俄罗斯运来的松木或者从南部和北部内陆购买的木材。17世纪欧洲贸易路线被封锁,在此期间,为汉萨工会贸易体系供应干鱼的中世纪聚落结构走向了没落。

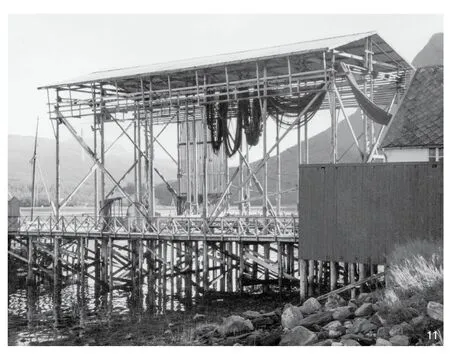

11 用于晾晒和储存渔网的架子,展现着20世纪30年代渔村的历史层。多样又特别的混合建筑样式是挪威北部海岸的建筑传统,也显示着基于粗糙木材的取材和建造传统。这张拍摄于塞尼亚岛的照片展示了一个用于晾干和储物渔网的架子;由巨大的树干组成的栏架Rack for drying and storing nets, 1930s manifesting the historical layer in the fishing villages. The tradition of building along the Northern Norwegian Coast is manifested by a mix of various but specialized building types, based on a construction—and material tradition—of rough wood. This picture from Senja shows a rack for drying and storing nets; a pole construction made of huge,straight-grown trunks, sourced from the Inner Troms region

随着北欧的工业化和城市化发展,鱼类市场以及相应的渔村在19世纪首次出现了蓬勃发展的趋势。挪威北部海岸变成了一个拥有吸引力资源的地区,成为除了美国之外的另一个移民目的地。2)生产和移居层(layer of production and resettlement)建立于19世纪到“二战”前的几十年间,在改善后的港口、临港的木制工业建筑、用于农产品生产的新灌溉形式和耕种的土地,以及传统住房类型中都可以观察到。

欧洲渔业在19世纪就已经实现了工业化。挪威有意寻找新的政策,用以改善粮食生产,提高渔业效率并实现沿海地区的现代化。在战后的几十年里,工业化和现代化是整个欧洲的口头禅。挪威社会民主政府意图将兼职农民或渔民转变为专业专职人员,将他们的妻子和女儿转变为渔业工人。这意味着生产结构的根本性改变,从咸鱼和干鱼工艺转向冷冻鱼技术,鱼片产品走入国际市场。并且,为满足全年资源供应,远洋拖网捕捞船队将成为现代渔业的统领。工业化适用于新型和不断发展的冷冻鱼市场,在这里鱼运上岸后就冷冻储存,切片后出口。3)工业化和现代化层(layer of industrialization and modernization,图12)明确地体现在新兴产业建筑、工业码头、产业工人居住区中。

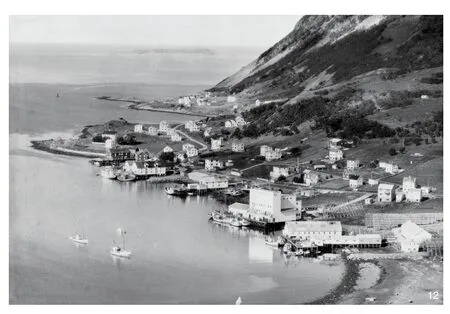

12 20世纪50年代末,韦斯特龙迈尔的用于冷冻切片工业的现代主义建筑,展现出工业社会物质层。战后挪威的渔业开始了以拖网渔船、冷冻机和鱼片加工流水线为基础的系统的工业化进程。图片中迈尔港已经开启了工业化的未来Modernist buildings for fillet-freezing industries, Myre, Vesterålen, late 1950s, manifesting the industrial socio-material layer. Systematic industrialization of the fisheries started in post-war Norway, based on trawlers, freezers and fillet-lines. Here the industrial future has arrived in Myre harbor

20世纪50—70年代的地区社会民主主义政策,促使挪威渔村进一步向社会化发展。4)社会民主福利层(layer of social democratic welfare)由此建立。在这一时期,挪威农村实现了现代化和城市化,但更多的是依托于系统性的权力下放,而非中央集中控制。主导的福利观念提倡所有居民都应享有同样的社会和文化服务。市政福利职能的范围扩大了,创造了公共行政和服务的新的工作场所。新建筑的需求,如:市政厅、中学、体育和游泳馆、保健中心、疗养院和多功能教堂,接踵而至。权力下放政策和经济的繁荣使得人们的财力和购买力不断扩大。贸易和商业、商店和汽车销售进入以前没有享受过此类服务的农村地区,创造了就业机会。部分工业生产,如造船业和建材产业,从城市迁出,由于工业创新,使得如塑料制品和建筑构件的制造出现在了乡村。

5)自由市场经济和全球化生产层(layer of marked liberal economy and globalized production)建立。挪威的渔业工业生产体系在20 世纪90 年代瓦解是其成因。欧洲去工业化进程体现着全球资本主义的逻辑,资源、生产和市场在国际、国家和地方之间重新调配,大部分的制造业转向了亚洲,也导致了地方性的灾难。鱼片价格跌至国际标价,从利润上看,把冷冻鱼运到中国生产鱼片,成本更低,之后,再把这些商品装入五颜六色的包装,运回欧洲和美国市场,甚至回到它的原产地——挪威北部的渔村,供应消费。市场和生产的变化导致了大规模破产,工业被废弃,工业建筑被拆除,工业设备被清算,社会环境恶化。然而,与许多欧洲沿海聚落不同,这一变化并不意味着挪威渔村的终结。从工业化时期再到全球鲜鱼市场的建立,挪威传统的小型船队一直保持着竞争力。鳕鱼在捕捞后仅几个小时内,就被去除内脏,黑线鳕被制成鱼片,放在聚苯乙烯泡沫塑料盒里的冰上,成为国际物流网络中的一件商品,通过洲际空运系统运往东京和上海。

这种生产体系意味着低薪劳动力的季节性引进和迁移,从福利和工人权利来看,从东欧国家低成本招募的工人很少得到关注。来自罗马尼亚和波兰的工人从船上接手捕捞上来的鱼,运送至生产线。有人可能会认为,这种情况在欧洲所有需要人力收获的农业生产中都是典型和正常的。挪威区域政策的一个主要目标是确保整个国家领土都有人口居住,并保证粮食的基本生产和现有的聚落结构,而超负荷的季节性劳动力引进威胁着这个目标。

6)再工业化层(layer of reindustrialization)在北大西洋沿岸、北极和巴伦支海沿岸的渔村中有迹可循。在这里它得到了政治和财政上的支持,欧洲表现出想要恢复制造业的迫切意愿。今天,我们可以找到鲑鱼养殖的不同模式,一些案例展示了技术的进步如何影响鱼类生产加工,以及当中涉及的自动化技术和系统的革新。与此同时,传统的船队以高科技为基础,也变得越来越先进。这些变化要求受过良好教育的高素质劳动力,为小型生产、小型聚落以及现代化的农村生活方式开辟可能性。

5 聚落和地域组织的语境挑战

北大西洋沿岸资源价值高,景观生产模式正在改变。运送到港口的捕捞物的所有部分都被利用,且利用方式不断创新,例如:从中获取新的制药产品。同时,旅游业的潜力也或多或少得到开发。极昼极夜现象与自然风景是主要的吸引点,围绕着渔业、极光、极夜和骤劣天气的观光游览项目呈现上升趋势。近几十年来,海水养殖业有所扩大,尤其是鲑鱼养殖和出口。包括传统渔业的海鲜产业,以及石油、天然气和电能,是挪威出口的主要部分。

不同的转型力量都会影响本土和区域的渔业景观的未来。目前,除野生鲑鱼外,多数的资源储备似乎都相当丰富,并依托监管政策得到了良好的管理。理论和实践经验证明,气候变化和全球变暖将提高海洋温度,改变海洋生态系统,将北极模式推向更北。这似乎在短期内就能观察到。全球变暖将长期持续,最终改变现有的墨西哥湾暖流的走向,对挪威沿海气候产生巨大影响。石油和天然气开采活动向北大西洋和巴伦支海扩展,占据更多的海岸线,对定居人口形成威胁,挑战着对劳动力最具吸引力的渔业。与此同时,许多国家都在争夺迄今为止隐藏在更北端的北极矿产和能源资源。除不断增长的环境污染风险外,渔业景观受到的影响还体现在俄罗斯北部水域的冰川融化,以及逐步发展的巴伦支海的运输通路。观光产业和大众旅游成为吸引投资和景观利用的一种替代方式,这将对聚落产生影响,但对船队和工业的影响甚微。更具决定性的是改变区域政策,包括政府针对市场推动的渔业重组政策,以及对资源和捕捞权的重新分配。迄今为止,挪威是少数几个能够长久保持健康、高科技的小型沿海船队的国家之一。

6 渔村——未来格局

整体而言,欧亚大陆的农村地区都受到席卷整个地域的强大的改造力量的影响,而乡村可以被理解为真实的深层结构,是景观、生态、生产链和聚落的复合体。中国农村保持着长期的相对稳定的聚落结构,而欧洲农村一直在发生变化。早在18世纪末,工业化就影响了欧洲农村,比中国的工业化早了170余年。20世纪70年代,中国开始在全球化进程中繁荣起来时,而欧洲则处于去工业化状态。今天,我们看到强大的中国政府和坚定的乡村政策。在欧洲,20世纪90年代出现了一大批发展农村基础设施的行之有效的举措,而到了今天,在政策方面,农村地区反而在某种程度上被忽视了,它们受制于市场压力,这一状况在农业生产、渔业、海产品工业和乡村聚落方面,影响显著。

大西洋沿岸的渔村一直是国际经济的组成部分,人们适应了当地的生态环境和贸易的逻辑。此外,今天的村庄依靠本地的实践技能来应对和适应工业经济、新技术和全球市场的影响。我们发现了一种既稳定又不断变化的人文活动的物质模式。在研究工作中,我们根据潜力定义了5种不同类型的村庄——可能与其他乡村语境存在共通③。

1)具有游憩功能的废墟空间(recreational ruins)。这类村庄在古老的繁盛时代产生,是如今难得的废墟景观。许多废墟景观都因休闲娱乐目的而得到维护,用于通勤者、老年人和退休人员居住,或用作度假使用。一些废弃的村庄被重新打造成旅游目的地。此类村庄已经是当代欧洲乡村中典型的聚落形式。废墟也可以被视为重组和中心化进程的产物。2)衰落的渔村(fading fishing villages,图13)。在罗弗敦群岛或芬马克村庄的“核心地区”,这类村庄是捕鱼配额竞争中的失败者,在吸引年轻家庭定居和为工业和参与季节性渔业的船只提供港口方面同样失利。鳕鱼渔业受到重大变革力量的影响:首先是鱼类配额制度,因为它可以在市场上出售,也会导致所有权和船队的结构性改变;其次是渔业所有权集中在少数人手中;然后是国际资本的进驻;最后是生产投资的数字化和资源加工的自动化。总体上,这导致了大容量船只的增加和活跃港口数量的减少。渔业的行业竞争和对于经济原则的更加依赖,不太明晰的所有权结构,以及处于变化中的船队和捕捞配额,影响着聚落结构,此类村庄似乎无法应对这些变化。村庄的实际社会功能在逐渐消退。3)劳工营地(labor campsis,图14)。这类村庄在生产方面具有相当优势,包含工业化生产,是构成社会和文化的独立场所。专业化工业区在鳕鱼捕捞季被用作基地和港口,来自低收入国家的工人被雇佣进行劳动作业,向本国其他地区运送渔获物,这是挪威渔业聚落的新的形式,这里的运行模式更像是劳动力集散地而非社会。4)创造性的小村庄(inventive hamlets)。这类村庄对于大多数困难似乎都能够应对。我们还意外地观察到,一些看似衰落的村庄,在创新型人才、自动化技术、水产养殖和新产品的影响下,恢复了生机。挪威渔业、船队和陆上生产基地,在过去的10年中已被重新定义为海鲜产业。在2019年出口的270万t海鲜产品中,三文鱼和其他种类的红鲑的产量达150万t。水产养殖业中,先进的生物和数字技术以及机器人技术开始应用于食品生产中,这也将影响白鲑鱼产业的生产方式。5)当代的稳定性村落(contemporary stabile villages)。这类村庄是从渔业发展成形的完备的城镇社会,拥有捕捞配额和现代化家庭船队,建立了本土文化自信和身份认同,拥有吸引来访船只参与季节性渔业的港口,是一个渔业复合体和为船队及产业服务的技术先进的机构。挪威北部海岸线的村庄聚落已经是一段历史,而渔业在陆地和海洋上的印记从未间断,继续构建着北极景观的未来。

13 塞尼亚的格吕勒峡湾——在20世纪,格吕勒峡湾可以被看作塞尼亚的主要渔村。而如今成了一个只有380人的衰落的渔村。经历了20世纪90年代冷冻鱼片行业的危机之后,格吕勒峡湾作为冬季的港口无法吸引足够的船只停靠,本地船只也在捕捞配额和资金的竞争中失利。格吕勒峡湾的产业今天已由Nergård AS经营,Nergård AS是挪威鳕鱼渔业的主要经营者之一,Nergård AS还在邻近的格伦法恩斯和森亚霍彭渔港经营产业,在格吕勒峡湾的产量十分有限Gryllefjord, Senja. Gryllefjord, during the 20th century, could be named the major fishing village in Senja. Today the populatins counts only 380 inhabitants and Gryllefjord is a fading fishing village. After the crises in the fillet-freezing industries in the 1990s,Gryllefjord has not been able to compete as a harbour for visiting boats during the winter season, and the local boats have relatively speaking, also lost in the competition for quotas and funding. The industries in Gryllefjord today is run by Nergård AS, one of the major actors in the Norwegian cod fisheries, Nergård AS also runs industries in the neighboring fishing harbors Grunnfarnes and Senjahopen, and the production in Gryllefjord is limited

14 森亚霍彭的渔船(2019年)——挪威捕鱼船队主要由“传统”船只组成,它们体量很小。渔民拥有自己的船,他们的渔获量受配额限制,配额可以买卖。这些船只都配备十分高效的电子和机械设备Fishing boats in Senjahopen, 2019. The Norwegian fishing fleet mostly consists of so called “traditional”, rather small vessels. The fishermen own their boat, their catch is regulated by quota, that might be sold or bought. These boats are very effective and utilize all available machinery and digital equipment

声明:

文章大部分内容参考以下3篇文章:

ELLEFSEN K O, LUNDEVALL T. North Atlantic Coast: A Monography of Place[M]. Oslo: Pax Publishers, 2019.

ELLEFSEN K O, HAUGLIN E A. Coastal Mapping Research Seminars[EB/OL]. [2022-07-27]. https://coastalmapping.no/.ELLEFSEN K O, TVARES A, DE SOUZA D I. Notes on Codfish Architecture[M].Lisbon: Cadernos da Garagem,2020.

注释:

① 文化生态位建设是第一个生物学概念。参考文献[2]和[3]是受到我们在奥斯陆建筑与设计学院的同事汉纳斯·赞德和他的中国河西走廊研究的启发。

② 挪威语skrei(Gadus morhua),是全年大部分时间生活在北极圈和巴伦支海的一种鳕鱼,不像其他普通的沿海鳕鱼那样主要生活在峡湾和大西洋。Skrei的生物习性包含每年一次去往南部的洄游。

③ 类型的详细介绍参见网站:https://coastalmapping.no/。

图片来源:

图1下载自ArcGIS Hub, World Countries;图2来自挪威地图编录(The Norwegian Catalogue of Maps,https://kartkatalog.geonorge.no)和GEBCO网格深测数据(GEBCO Gridded Bathymetry Data);图3来自挪威渔业理事会;图4~9、13、14来自海岸测绘研讨会(2017年,https://coastalmapping.no/);图10由卡尔·奥托·埃利弗森、塔哈德·伦德瓦尔拍摄(2016年);图11由南特罗姆瑟博物馆提供;图12由北部博物馆、奥克斯内斯博物馆提供,菲耶兰格尔·威德罗拍摄。

(编辑/刘玉霞)

The Imprint of Fisheries on Land: The Logics of Settlement Structure and Place in an Arctic Landscape

Authors: (NOR) Karl Otto Ellefsen, (NOR) Espen Aukrust Hauglin Translator: WANG Wei

Anne Whiston Spirn did introduce the concept “deep structure” to denote the enduring stability of landscapes: “to which all organisms within that landscape respond. Deep structure expresses the fundamental climatic, geomorphic,and biotic processes in a particular place. Deep structure is the product of these processes operating and interacting across vast scales of time at the scale of large regions and at the microscale.”The deep structure is formed by the characteristics of territory and site: global localization, geological and climatic factors which “yield landscape structure with distinctive spatial, physical, and temporal characteristics.”[1]

Deep structure represents resources and establishes the basis for ecosystems, habitats and social and environmental processes. In the words of Spirn,“in response to natural processes and changing human purposes.”[1]Humans interact with ecosystems and transform environments, even consciously engineer the systems, creating what Charles L. Redman has conceptualized as “socialecological systems”[2]. However, these systems are in no way stabile. There is a continuous process(according to Erle C. Ellis) of “socio-cultural niche construction” where human alter environments and ecosystems to their needs[3]①.

While the logic of production of landscape(as opposed to wilderness) historically was directly linked to site specific vertical forces, global production chains and markets have made local landscape subject to horizontal forces outside the local and territorial niche.

The concept coping or coping strategies describe how societies change in order to exploit new conditions[4-5]. Coping concerns how people and societies make the most of opportunities or more specifically engage in strategies they themselves find significant, and with a term from Henri Lefevre,produce space according to their needs[6].

When discussing how a society and its landscape and architecture relate to each other, it is expedient to see the built environment as a series of socio-material layers to denote the different historical structures, “in each socio-material layer,one can trace the connections between the built environment and the life that unfolded within this material field. These surroundings are both a framework around a way of life as well as living cultural expressions”[7].

1 Deep Structure

Norway faces the North Atlantic to the west and the Barents Sea to the north. From the southern lighthouse at Lista to the northern city of Vardø the distance is measured to be 1,789 km[8].Following the rugged coastline around the fjords the coastline is estimated to stretch 100,915 km[9](Fig. 1). Only Canada can boast a longer coastline.The Arctic Circle (66°33′ 45″ N) — the theoretical boarder for midnight sun and dark polar nights— crosses the country at Saltfjellet about 800 km from the most northern point of Norway. In terms of geography this means that most of Northern Norway belongs to the Arctic or more precisely the Sub-arctic area, defined as the transition zone between the tree line and the areas with boreal coniferous forest. However, due to the Gulf Stream the coastal climate is rather mild, only on the eastern peninsulas of Finnmark — the county to the utmost north — we find an arctic climate similar to Siberia, Alaska and Northern Canada.Situated north of the isotherm delineating a zone of no summer, with lower than 10℃ middle temperature for July.

Most of the North Atlantic Coast is characterized by steep barren mountainsides —the tops going up to maximum 1,800 meters —bordering the fjords, narrow and deep channels that allow the sea to enter into the land. The geology is dominated by the Caledonian mountain range. The archipelago of Lofoten, Senja and Vesterålen, the core area of the cod fisheries stretching out into the ocean, is constituted by hard pre-Cambrian bedrock. The geomorphology is varied. In Finnmark 95% of the land lies lower than 500 meters, the sediment covering the downgrinded bedrock nourishing a biome characterized by the lack of trees and mainly covered by mosses and lichens. To the south, along the fjords and on the islands, the land offers what in Norwegian is called strandflater, flat grassy land between the shoreline and the mountains.

In a territory where people historically have lived more of what the sea can offer than the products of the land, the bathymetry (Fig. 2) is an essential part of the deep structure. The rugged coast with islands and fjords corresponds to an extremely varied subwater geomorphology. Two different territorial systems are decisive for the fisheries and therefore for the localization of the fishing villages. The shallow waters along the coast from Vestfjorden south of Lofoten and northwards plunge down to towards the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean (Norwegian Basin), this bathymetric edge called Egga. The sea-bottom along the coast of Finnmark towards the Barents Sea on the other hand, has the character of a continuous shallow fishing bank. The two systems are the basis of two different interfacing ocean ecosystems.

2 Resources

In an international market, the scarce agriculture of Northern Norway cannot survive without subsidies and generous regional policies.The northern coastal waters of the Atlantic and the Barents sea are on the contrary contain fishresources that are probably the most abundant in the world. The Atlantic cod orskrei, is — in terms of historic influence on production systems and settlement structure — the primary resource in the ecosystem②. The annual winter migration ofskreifrom the Barents Sea and southwards, provides the basis for fisheries from January to April. The cod following the current and nourishing waters along Eggato the spawning grounds in Vestfjorden south of the Lofoten archipelago. Most of the many cod fisheries in the world are now history. The Newfoundland fisheries, once so important for the Portuguese, and later for the US and Canada,vanished due to overfishing. So far, the Norwegian management of fishing resources has been rather successful for most of the specimens found in the vast national economic zone and the fishing zones surrounding Spitzbergen and Jan Mayen islands. Referring to the bathymetry, the course of the Gulf Stream and difference in latitude, the ecologies of the Atlantic and the Barents Sea differs both in terms of pelagic fisheries (herring, mackerel,capelin, tobis and other schooling fish) and demersal fisheries (mostly whitefish, apart from cod, haddock and pollock are the most abundant, Fig. 3).

The resources for agriculture, livestock and arable farming was found in the sediments on Strandflatene, flat areas with sediments possible to cultivate along the fjords and on the islands.Potatoes, carrots, cabbage and some berries were grown on vegetable land near the farms. The climate being too harsh for grain and fruit. Also the uncultivated nature was harvested. The Sami minority migrated from winter pastures of reindeer moss in the inland to grazing in the coastal areas in the summer. The land and sea were ripe with resources — hydropower, minerals, oil and gas —many of these still only a future potential.

3 Socio-Cultural Niche Construction

A characteristic of the cod fisheries is the relative stability of the production processes over time. Dried cod was the first Norwegian commodity that was accessible on the European market, this happening a thousand years ago.The mode of production was very simple. The gutted fish was hung on racks to dry. Especially the relatively warm, sunny and windy climate on the islands out in the Gulf Stream gave perfect drying conditions preventing frost and attacks from insects. Modern steel racks for hanging and drying cod remain technically and in terms of design very similar to the traditional drying racks constructed by wooden poles. In terms of professional and commercial life, urbanization implies specialization.Along the Northern Norwegian Coast, such specialization took place early because the stockfish became an international commodity, creating not only a commercial economy but also fishing villages that to a certain degree acted as specialized settlements with fishermen producing for an international market (Fig. 4, 5).

Factors that generated the territorial pattern of human action — the settlement structure —was the quality of the harbor, the distance to the fishing grounds, the relative dangers of the waters to reach the fishing grounds, the access to buildable land and the local agricultural resources.The use of the land was determined by a dialectic between the land and the sea. In times of good and safe northern and European trade-systems,like in the late middle-ages and during the North European industrialization in the late 19th century,the fishing villages prospered. When trade routes were unstable, fish-prices low and grain difficult to buy, people moved from the fishing villages to the fjords to cultivate land for agriculture.

A fishing village is not a clear cut statistical or geographical term. In the fishing village,fishermen have their berth for their boats in the harbor, and the initial sales of their catch — the first transaction between the fisherman and the fish-buyer/producer — takes place in the village.However, the fisherman does not necessarily live in the village, he might be a seasonal worker fishing from the harbor. The historical settlements along the Northern Norwegian coast have often been described as the sum of small, individual farms where fishing produced cash. Where the agricultural resources were abundant and/or the fish were easily accessible, dens fishing villages would form, composed of many individual farms and farmhouses. Even though the fisheries followed patterns and techniques that were relatively identical along the entire coast, each place differed from the rest, depending on site, property conditions,modes of production and building culture. Along with the dispersed farms that combined fishing and agriculture —kombinasjonsbrukinNorwegian— the fishing villages represent the imprint of the fisheries on the settlement patterns of the North.

A fundamental distinction between different types of fishing villages can historically be drawn between the permanently populated villages,typified as dense agglomerations of small farms and the seasonal fishing villages whose economy was based on itinerant fishermen (Fig. 5-9). The fishing villages in the Lofoten archipelago were located in natural harbors close to fishing grounds with large seasonal drift of cod. They were owned by local, predominant landowners and the entire organization — with the landowner’s large white residence, the drying racks, the sheds by the piers for storing dried fish for export, and the many fishermen’s cabins located where the terrain and the harbor conditions made it possible to erect wooden constructions — encapsulating both the fishing production and the power relations in the fishing village. The oldest settlements are probably the permanently settled fishing hamlets located where agricultural resources were found.Many of them have roots back to the era when stockfish first became a tradable commodity and are structured according to the European medieval system of narrow properties from the sea to the foot of the mountain. During the late-nineteenth process of land consolidation, strips of farmland in the Norwegian countryside were redistributed and pooled together in order to develop more economically viable farming units and thereby supply a growing urban population. The process usually led to villages being broken up and the farmhouses relocated to the plot of land that the farming unit had been allocated to. By contrast, the consolidation in the fishing hamlets did not cause the dense cluster of farmhouses to be dissolved and relocated, because the fisheries, the boats and the harbor were far more important than farming.The fisheries were a joint venture and depended on the communal bound between those who toiled at sea and those who ran the farm and the household back home (Fig. 10).

The fishing village as a settlement form was established as socio-cultural niches, habitats and settlement forms along most of the Norwegian coast, from Møre in Western Norway to Finnmark in the very north. Some, where located desolately,and are now abundant. Some turned into cities where the fishery sector by now is of little importance. The structure of fishing villages is today most viable in the core area for the Atlantic cod — Lofoten, Vesterålen, Andøya and Senja— and along the coast of Finnmark where the resources are accessible all year and intensive fisheries initiated from the 19th century onwards.

4 Socio-Material Layers

Investigating the history of the fishing villages,their changing landscapes, the way the villages are organized and the architecture, one distinguishes a set of overlapping socio-material layers[10]. The term is obtained from the social theorist Dag Østerberg in order to denote historical structures in urban architecture. In each individual socio-material layer,one can trace the connections between the built environment and the life that unfolded within this material field. That is landscape and architectural principles that reflect the time they were made as a tool for the production and way of life. This approach to understanding is parallel to André Corboz’ notion of the land as palimpsest and the systematic reading of different landscape layers that have accumulated over time[11]. The way of understanding also referring to structuralist theory for interpreting phenomena by diachrone(over time) and synchrone (today) investigations[12].

In our research we, according to a timeline,have distinguished between six different sociomaterial layers. There is a 1) historical layer (Fig. 11),today reflected and visible in the localization of the villages, the organizational principles for land-use and buildings, and in the structural principles for the wooden architecture, built from pine material drifted from Russia or brought from the woods to the south or the inland of the north. The medieval settlement structure that had supplied dried fish to the Hanseatic trade system, to a large extent was abandoned in the 17th century when European trade routes were blocked.

A strong growth in the marked for fish and accordingly in the villages first happened in the 19th century along with North European industrialization and urbanization. The North Norwegian coast turned into an area with attractive resources at hand and a destination for migration,in fact an alternative for emigration to the US.2) A layer of production and resettlement was established from the 19th century through the decades towards the Second World War. This layer is observable in improvement of harbors,in the wooden buildings of the industries along the harbor fronts, in new drained and cultivated land for agricultural production and in traditional housing typologies.

Industrialization happened in European fisheries already during the 19th century. And the new policies were looked upon in Norway with interest, in order to improve food production, to make the fisheries more effective and to modernize coastal areas. In the first decades of the postwar period, industrialization and modernization were mantras for all Europe. The intention of the Norwegian social-democratic government was to transform part-time farmers/fishermen into specialized professionals, the wives and daughters becoming workers in the fishing industries. This implied a fundamental change in production, from salted and dried fish to frozen fish technology, the production of fish-filet to an international marked and — in order for all year supply of resources —a modern open sea going fleet for trawling. The industrialization adapted to a new and growing marked for frozen fish, with the fish being landed to be stored frozen, filleted later, then exported.3) A layer of industrialization and modernization(Fig. 12) is apparent in buildings for the new industries, in industrial harbors and in housing areas for the workers in the industries.

The fishing villages were further developed as societies due to social democratic regional policies in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, establishing 4) a layer of social democratic welfare. In this period the Norwegian countryside was modernized and urbanized, but more due to systematic decentralization than to centralization. The predominant welfare philosophy stated that all inhabitants should have access to the same social and cultural services. The scope of municipal welfare functions increased and created new workplaces in public administration and services.And the need for new buildings, like town halls,secondary schools, sports and swimming halls,health centers, nursing homes and multipurpose churches. The policy of decentralization and the booming economy led to people having more money and purchase powers. Jobs in trade and commerce, shops and car sales, were created in rural areas that had not previously enjoyed such services. Part of the industrial production — for example within the shipbuilding industry and the construction material industry — moved out from the cities, and industrial innovation took place in the countryside, for example the making of plastic products and building parts.

The Norwegian industrial production system in the fisheries fell apart in the 1990s leading to the establishment of 5) a layer of marked liberal economy and globalized production. There were many local, national and international reasons for what turned out to be local disasters, but as a whole we have to see the change as part of the European deindustrialization, through which most production was moved to Asia, due to the logic of global capitalism. The price of fish filet fell on the international marked, and, in terms of profit it became cheaper to send frozen fish to China, for fillets to be produced there, and then bring this commodity, put into neat and colorful packages, back to Europe or to the US markets or even back to its origin, the fishing villages in the north ,for consumption. Changes in markets and production ended up in bankruptcies, industries being abandoned, industrial buildings being torn down, industrial gear being liquidated and societies deteriorating. But to the contrary of many European coastal settlements this was not the end of the Norwegian fishing villages. The traditional fleet of small vessels had always been competitive,including during the industrial period, and eventually a new, profitable global marked for fresh fish emerged. Just a few hours after being caught the cod is gutted and the haddock made into filet,put on ice in Styrofoam boxes and transformed into an object within a web of international logistics,even as part of an intercontinental airborne system which takes fresh cod to Tokyo and Shanghai.

A downside to the production system is that it implies seasonal import and migration of low paid and in terms of welfare and worker’s rights, little cared for workers recruited in low-cost countries in Eastern Europe. Romanian and Polish workers angle the lines, receive the fish from the boats and handle the catch through production.One might state that the situation is typical and normal in all agricultural production in Europe in need of manpower to harvest. A major intention in Norwegian regional policies is to keep all the country populated and also to sustain primary production of food and the existing settlement structure. The overwhelming import of a seasonal work-force is a threat to these ambitions.

We find traces, and there is political and financial support for developing 6) a layer of reindustrialization in the fishing villages along the North Atlantic and coast to the Arctic and Barents sea. This may be seen in the context of the urge to return production to Europe. Today we may look to different models in salmon farming, and find examples showing how the production of fish is undergoing subtle technological progress involving robotics and ingenious systems. The traditional fleet is, at the same time, becoming more and more advanced and based on high technology. These changes require a well-educated workforce of high competence, and open up possibilities for both down-scaled production and small settlements, and a modernized rural way of life.

5 Contextual Challenges to Settlements and Territorial Organization

The landscape of production along the North Atlantic coast is changing. The monetary value of the resource is high. All parts of the catch being delivered in the harbors are used, and there is a lot of invention going on; for example,new pharmaceutical products are being subtracted from the catch. There is also, of course, a more or less exploited potential for tourism. The midnight sun combined with the scenery of nature are the main attractions, but there is also a growing winter tourism based on the fisheries, the northern light,the continuous darkness and the dramatic climate.During the recent decades marine aquaculture has expanded, mostly the breeding and export of salmon. The seafood industry, also including the traditional fisheries, oil, gas and electric energy, are the main elements of Norwegian export.

Different transformation forces will interfere with the future local and territorial landscape of the fisheries. Most of the specimens in the resource, with the exception of wild salmon, seems at the moment rather abundant and well managed by regulating policies. Theory and empirical material prove that climate change and global warming will raise the ocean temperature altering marine ecosystems and driving the arctic specimen further north. This seems observable also within a relatively short time-frame. Global warming,eventually in the long run, changing the current of the Gulf Stream, will have dramatic effects on the Norwegian coastal climate. The extension of oil and gas activities to the North Atlantic and the Barents sea will compete with established use of ocean banks, represent a risk for pollution and challenge the fisheries for the most attractive labor-force. At the same time many countries are competing for the access to so far hidden arctic mineral and energy resources further north. The eventual effects on the landscape of fisheries by the de-icing of the waters north of Russia and the gradually evolving Barents Sea transport connection are disputed,except the increased risk of pollution. Travelers and mass-tourism as a potential for alternative investment and an alternative use of landscape will have influence on the settlements but hardly on the fleet and the industries. More decisive are the potential for change in regional policies and the possible governmental urge for a marked driven reorganization of the fisheries and a new distribution of rights to the resources and the catch. Norway is one few countries that so far has been able to sustain a healthy, high technology,small vessel based coastal fleet.

6 Fishing Villages — Future Typologies

Generally, the rural areas in Eurasia are subject to strong transformation forces all over the continent, but the countryside might also be understood as a complexity of very genuine deep structures, landscapes, ecologies, production chains and settlements. While there has been a relative stability over a long time in the Chinese rural settlement structure, rural Europe has been changing. Industrialization affected the European countryside, already in the late 18th century.170 years before industrialization happened in China. While China prospered from globalization from the 1970s and onwards, Europe was deindustrialized. Today we see strong government and ambitious rural policies in China. In Europe a huge program for developing rural infrastructure worked in the 1990s, but today in terms of policies,rural areas are somehow neglected and being subject to marked forces, with a profound effect on agricultural production, the fisheries, the sea-food industries and rural settlement.

The fishing villages along the Atlantic coast were always part of an international economy and the people adapted to the ecologies on site and to the logics of trade. Also, today the villages are depending on local abilities to cope and adapt, to industrial economies, the use of new technologies and to global markets. We find a physical pattern of humane action that are both stabile and changing.In our work we have defined five different categories of villages — possible also relevant for other rural contexts — according to their potentials③.

Recreational ruins are picturesque ruin landscapes from bygone heydays of production.Many of these ruin landscapes are maintained for recreational purposes, used as homes for commuting, for the old and retired, or as holiday homes. Some of the abandoned villages are rebranded as tourist destinations. The recreational ruin is a very typical contemporary settlement in the European countryside. The ruins might also be seen as the outcome of a process of re-structuring and centralization. Fading fishing villages (Fig. 13)are losers in the competition for fishing quotas,to attract young families to settle, for industries and harbor for vessels taking part in seasonal fisheries, in Lofoten, in the “core area” or in the Finnmark villages. The cod fisheries are subject to major transformation forces. One of these is the system of fish-quotas, quotas that might be sold on the marked, leading to structural changes in ownership and fleet. Another is the tendency to concentrate ownership in the fishing industries on a few hands. A third tendency is international capital entering into the industries and a fourth are investments in digital production and robotization in the processing of the resources. Generally, these tendencies have brought about boats with larger capacity and a reduction of the number of active harbors. The competition and rationalization in the fishing industries, a less fine-grained ownership structure together with the changes in fleet and fishing quotas, affect the settlements. The fading villages seem not able to cope. Villages are gradually falling apart as viable societies. The labor campsis (Fig. 14) in terms of production a winner and contain industrialized production, independent of place as a social and cultural construct. In a Norwegian context, this is a new type of fishing settlement, a specialized industrial area employed by seasonal workers from low-cost countries, in the cod-season used as a base and harbor for delivering catch by fishing-vessels from other parts of the country, functioning more like a labor camp than a society. Inventive hamlets are small villages that against most odds seems able to cope. Surprisingly,we can observe a resurrection among a few of the seemingly fading villages due to inventive actors, robotics, aquaculture and new products.Norwegian fisheries, the fleet and the land-based production, have the last decade been renamed the Sea-food industries. Of the 2.7 million tons of exported sea-food in 2019, salmon and other redfish production amounted to 1.5 million tons. The aquaculture industries initiated the use of advanced biological and digital technologies and robotics in the food-production. This will also influence the organization of production in the white-fish industries. A last category is the contemporary stabile villages that has developed into complete societies, towns primarily based on the fisheries,with a modern home-fleet equipped with quotas, a strong local culture and proud identities, a harbor attractive for visiting vessels taking part in the seasonal fisheries, a complex structure of fishing industries and a technically advanced servicestructure for the fleet and the industries. There is a history, but might also be a future for the historical use of the land, the sea and for the settlement structure along the Northern Norwegian coast.

Statement:

The article is partly based on text from three different publication by the author(s):

ELLEFSEN K O, LUNDEVALL T. North Atlantic Coast: A Monography of Place[M]. Oslo: Pax Publishers, 2019.

ELLEFSEN K O, HAUGLIN E A. Coastal Mapping Research Seminars[EB/OL]. [2022-07-27]. https://coastalmapping.no/.

ELLEFSEN K O, TVARES A, DE SOUZA D I. Notes on Codfish Architecture[M]. Lisbon: Cadernos da Garagem,2020.

Notes:

① Cultural niche construction is a term from biology. The references [2] and [3] are inspired by our colleague Hannes Zander at AHO and his work on the Hexi corridor in China.

②Skrei(Gadus morhua) is a codfish that most of the year lives in the Arctic and the Barents Sea. As a species it differs somewhat from the ordinary coastal cod that lives in the fjords and in the Atlantic. The ecosystem ofskreiinvolves a yearly wandering to the spawning banks in the south.

③ The typologies are further exemplified on https://coastalmapping.no/.

Sources of Figures:

Fig. 1 source: ArcGIS Hub, World Countries (Generalized);Fig. 2 source: The Norwegian Catalogue of Maps(https://kartkatalog.geonorge.no) and GEBCO Gridded Bathymetry Data; Fig. 3 source: The Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries;Fig. 4-9, 13, 14 source: Coastal Mapping Research Seminar(2017), https://coastalmapping.no/; Fig. 10 photograph:Karl Otto Ellefsen and Tarald Lundevall (2016); Fig. 11©Sør-Troms Museum; Fig. 12©Museum Nord, Øksnes Museum,photograph: Fjellanger Widerøe.

(Editor / LIU Yuxia)