Current standard values of health utility scores for evaluating cost-effectiveness in liver disease: A metaanalysis

Tomohiro Ishinuki, Shigenori Ota, Kohei Harada, Masaki Kawamoto,Makoto Meguro, Goro Kutomi, HiroomiTatsumi, Keisuke Harada,Koji Miyanishi, Toru Kato, Toshio Ohyanagi, Thomas T Hui,Toru Mizuguchi

Abstract

Key Words: Quality of life; EuroQOL 5-dimensions 5-levels; Short from-36; RAND-36; Health Utilities Index-Mark

lNTRODUCTlON

The quality of health is an important factor when assessing medical management rather than simple survival periods[1,2]. Health utility is an important factor in medical assessments and socio-economic politics[3]. National health budgets have risen steadily in various countries, and governments need to deeply consider the need to maintain a socio-economic balance[4]. Therefore, health benefits should be compared with social costs to avoid national financial collapse.

It is difficult to quantify health quality at regular intervals[5]. We are developing wearable devices that can automatically obtain health data, including data regarding mental health. Some health utility assessments require the use of questionnaires, which are associated with low compliance and involve bothersome calculations[2,6,7]. Before launching our novel health utility assessment tool, we performed this meta-analysis in order to summarize the currently available health utility assessment tools. The most useful questionnaire for evaluating health status depending on liver disease status or sex is unclear. In addition, no universal health utility assessment values for specific liver diseases or the normal population have been reported. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to estimate health utility assessment values for specific populations.

The EuroQOL 5-dimensions 5-levels (EQ-5D-5L) is the simplest instrument for evaluating health utility and has been widely translated into various languages with high reliability and validity[6,8-10]. It only involves five questions and five answering levels. The health utility scores produced by the EQ-5D-5L can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life year (QALY) values[8]. The Health Utilities Index Mark 2/Mark 3 is another instrument for evaluating health utility scores and can also be used to obtain QALY values[11]. However, the Health Utilities Index is complicated, as it involves 45 questions, which take a long time to answer. The short-form 36-item (SF-36) is also widely used to evaluate health quality,although it does not directly involve QALY evaluations[9,12,13].

There are two types of SF-36, and the copyrights to these tools belong to The RAND Corporation(Santa Monica, CA, United States)[14] and QualityMetric (Johnston, RI, United States), respectively[15].However, most researchers do not actively consider which version they use[12]. Therefore, the exact method and results of such assessments are not always described in the literature (Table 1).

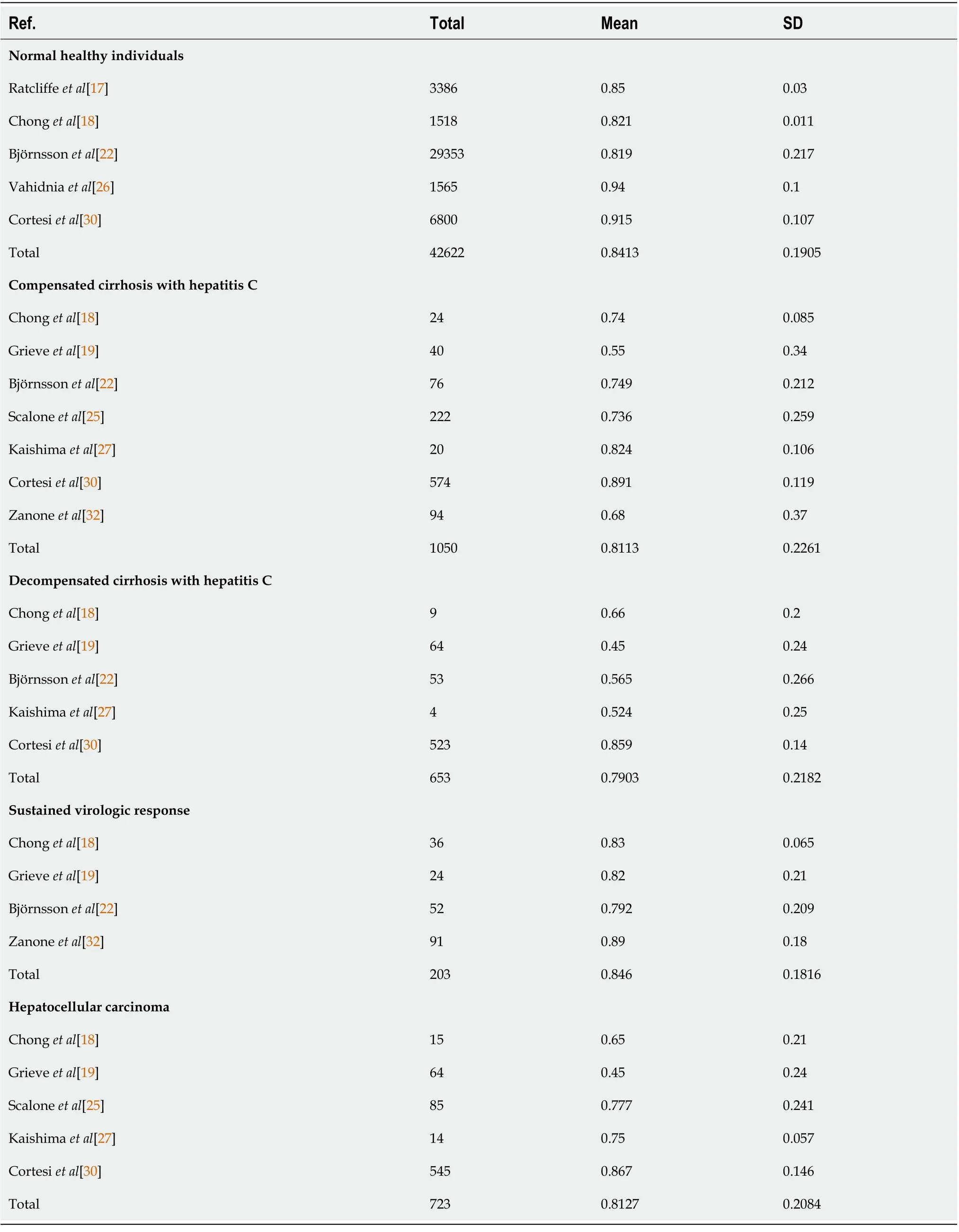

In this meta-analysis, we describe the scores obtained with various health utility indexes (HUIs) in normal healthy populations or patients with different types of liver disease (Table 2)[16-32].

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Literature search

The PICOS scheme was used to set appropriate inclusion criteria. A systematic literature search of PubMed and MEDLINE, including the Cochrane Library, was performed independently by two authors(Ishunuki T and Ota S). The search was limited to human studies whose findings were reported in English. No restrictions were placed on the type of publication, the publication date, or publication status. The search strategy was based on different combinations of words for each database. For the PubMed database, the following combination was used: (("liver"[MeSH Terms] OR "liver"[All Fields]OR "livers"[All Fields] OR "liver s"[All Fields]) AND "qol"[All Fields]) AND (1990/1/1:3000/12/12[pdat]). For the MEDLINE database, the following combination was used: [quality of life(QOL) and Liver].

Study selection

The two independent authors screened the titles and abstracts of the primary studies identified in the database search. Duplicate studies were excluded. The following inclusion criteria were employed for the meta-analysis: (1) Studies that compared QOL in patients who had liver disease; (2) Studies that compared QOL between male and female patients with liver disease; (3) Studies that reported at least one QOL outcome; and (4) If the same institute reported more than one study, only the most recent or the highest-level study was included.

Data extraction

The same two authors extracted the following primary data: (1) The questionnaires used for each QOL evaluation; (2) The first author, year of publication, and type of study; (3) The etiology of the disease and the number of times each intervention was performed; and (4) The timing of the evaluations.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using the RevMan software (version 5.3.; The Cochrane Collaboration).The mean differences (MD) between groups were calculated for continuous variables. The interquartile ranges of the data were transformed by dividing them by 1.35 to produce alternative standard deviation values. Multiple means and standard deviations were combined using the StatsToDo online web program (https://www.statstodo.com/index.php).

The chi-square test was used to evaluate heterogeneity, and the CochranQandI2statistics were reported. TheI2value describes the percentage variation between studies in degrees of freedom.Pvalues of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

EQ-5D-5L

The EQ-5D-5L has been widely investigated as a tool for evaluating general health in normal populations and patients with different stages of liver disease (Table 3)[17,18,22,25-27,30,32]. Health utility indices should be affected by age, sex, ethics, religion, and geography. However, the EQ-5D-5L produced similar utility indices for groups with different health statuses (Table 3), such as normal healthy individuals (0.8413 ± 0.1905) and hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients with compensated or decompensated cirrhosis (0.8113 ± 0.2261 and 0.7903 ± 0.2182), HCV-infected patients exhibiting a sustained virologic response (SVR) (0.846 ± 0.1816), and patients with hepatocellular carcinoma 0.8127 ±0.2084).

In general, the EQ-5D-5L produces significantly higher scores in males than in females (Figure 1A)(0.8267 ± 0.229vs0.7922 ± 0.239;P< 0.001). The mean total EuroQol-visual analogue scale score for the general population was found to be 79.796 ± 17.614 in two independent studies (Table 4)[26,30].

SF-36

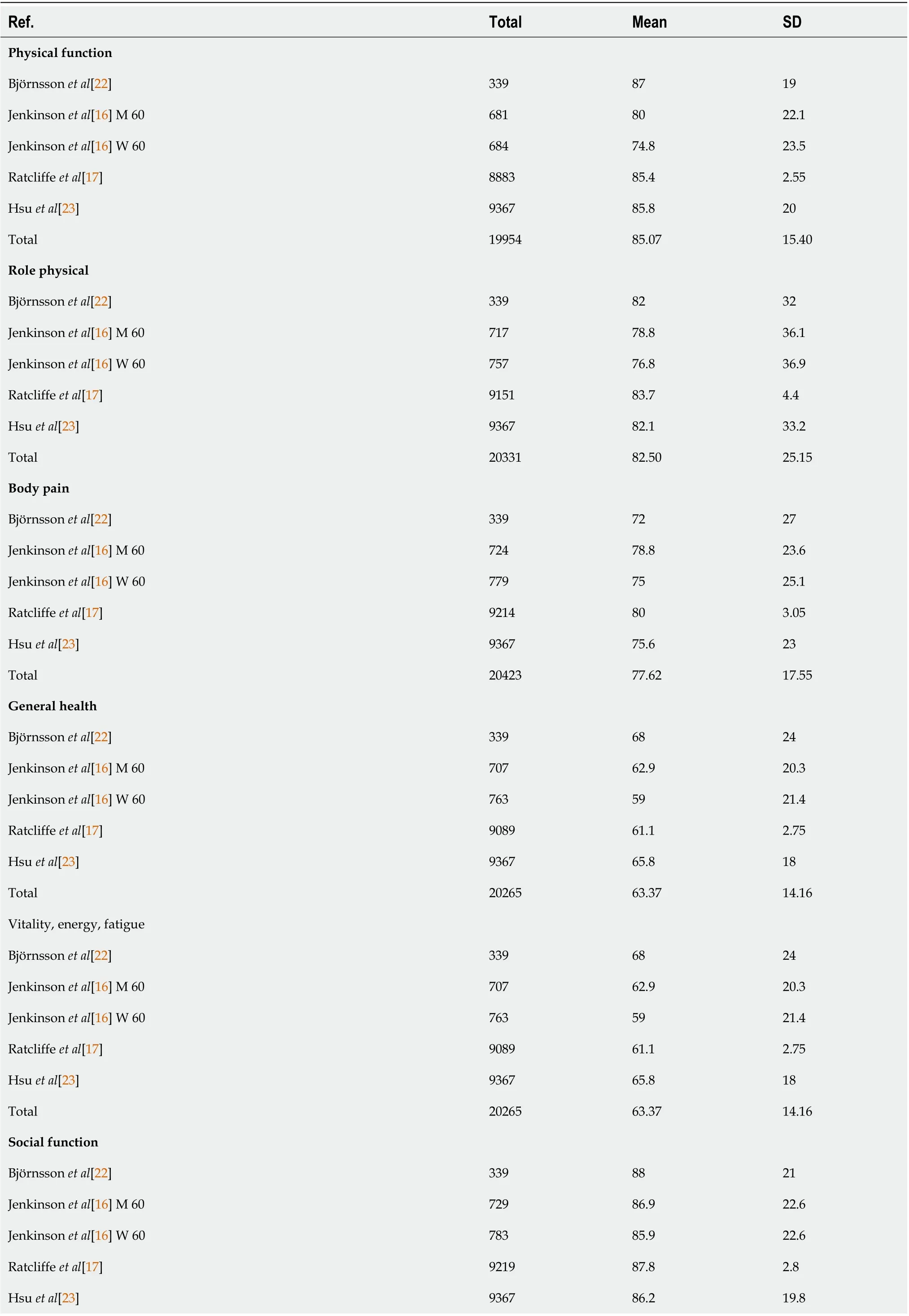

The SF-36 consists of eight scales, including physical functioning (85.07 ± 15.40); role limitations due to physical health problems (RP)(82.50 ± 25.15); bodily pain (BP) (77.62 ± 17.55); general health perceptions(GH) (63.37 ± 14.16); vitality, energy, or fatigue (VT) (63.37 ± 14.16); social functioning (SF) (86.97 ±15.13); role limitations due to emotional problems (RE) (83.94 ± 23.57); and general mental health (63.37± 14.16). Although the eligible healthy controls differed among countries and age groups, the health utility scores produced by each scale were similar (Table 5)[16,17,22,23].

Table 1 Current health-related outcome for liver disease

Table 2 List of previous studies and health utility assessments

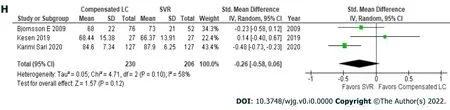

Compensated liver cirrhosis vs sustained virologic response

Patients with hepatitis C had achieved an SVR exhibited significantly better health utility scores for each SF-36 scale (Figure 2)[22,29,31] and the EQ-5D-5L (Figure 1B)[18,19,22,32] than those with compensated liver cirrhosis (Table 6)[18,19,22,29,31,32]. In particular, significant differences in the scores for RP (61.5± 31.6vs73.3 ± 27.3), GH (64.8 ± 20.9vs74.8 ± 18.5), VT (70.5 ± 24.0vs78.1 ± 18.4), RE (56.8 ± 32.0vs68.1± 27.3), and the EQ-5D-5L (0.6863 ± 0.3065vs0.846 ± 0.1816) were seen between these groups. These results indicate that health utility indices improve by 10%-20% after patients with hepatitis C achieve an SVR.

Table 3 EuroQol 5-dimensions 5-levels

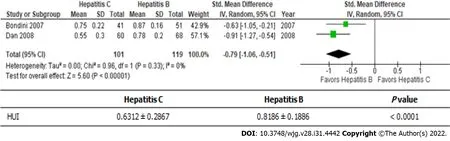

HUI Mark-2/Mark-3

Hepatitis B and C are the main causes of viral-associated chronic liver disease (Figure 3)[20,21]. The health utility scores of hepatitis B patients were significantly better than those of hepatitis C patients(0.6312 ± 0.2867vs0.8186 ± 0.1886);i.e., there was a roughly 30% difference between the scores of these patients.

Table 4 EuroQol-visual analogue scale in normal healthy individuals

Figure 1 EuroQOL 5-dimensions 5-levels. A: Men vs women; B: Compensated liver cirrhosis vs sustained virologic response. EQ-5D-5L: EuroQol 5-dimensions 5-levels.

DlSCUSSlON

Which HUI should be used for normal populations or patients with chronic liver disease?

In this meta-analysis, we summarized the findings of previous studies examining health utility evaluations in patients with chronic liver disease. Various questionnaires have been used to evaluate health utility in different populations/at different times. The EQ-5D-5L is the most popular of the questionnaires used to examine health utility scores internationally[17].

One of the concerns regarding the application of health utility scores is their sensitivity[33]. For example, the health utility scores produced by the EQ-5D-5L for patients with compensated cirrhosis and decompensated cirrhosis did not differ significantly (Table 3). On the other hand, the health utility scores for hepatitis C patients with compensated liver cirrhosis and those who achieved an SVR differed significantly according to both the SF-36 and EQ-5D-5L (Table 6). This indicated that both questionnaires are suitable for evaluating health utility in hepatitis C patients after viral elimination. Although the health utility scores derived from the EQ-5D-5L were calculated from 5 questions, the score range of the EQ-5D-5L (123.3%) was greater than that of the SF-36 (105.8%-119.2%). Therefore, the EQ-5D-5L could be suitable for evaluating health utility scores in this specific disease state. On the other hand, EQ-5D-5L-derived health utility scores are based on only five personal factors, mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Therefore, their sensitivity and any ceiling effects should be validated in each language and ethnic group.

It is well known that the prevailing subtype of viral hepatitis differs depending on the geographic region[34]. Hepatitis B is the prevailing subtype in East Asia[13], whereas hepatitis C is the most common in Western countries[35]. Both types of hepatitis can be controlled by nucleic acid analogs[36].In this meta-analysis, the HUI scores of hepatitis C patients were roughly 30% lower than those of hepatitis B patients. The differences between hepatitis B and hepatitis C need to be investigated using the EQ-5D-5L and SF-36 in future.

The second concern regarding the use of questionnaires for health assessments relates to the number of questions in each questionnaire. The EQ-5D-5L consists of only five questions[8], whereas the other tools consist of 36[14-16] or 45[11] questions. The number of questions affects study compliance,especially in the elderly[37]. If possible, the number of questions should be minimized.

Table 5 Short from-36: Healthy controls

Total 2043786.9715.13 Role emotional Björnsson et al[22]3398629 Jenkinson et al[16] M 6071485.829.5 Jenkinson et al[16] W 6075683.332.5 Ratcliffe et al[17]915983.74.4 Hsu et al[23]93678431.7 Total 2033583.9423.57 Mental health, emotional, well-being Björnsson et al[22]3395010 Jenkinson et al[16] M 606977817.5 Jenkinson et al[16] W 6074274.418.5 Ratcliffe et al[17]901474.62.35 Hsu et al[23]936777.515.3 Total 2015975.6412.23

Table 6 Compensated liver cirrhosis vs sustained virologic response

The last concern is about gaining permission to use such questionnaires for health utility assessments.It takes great effort to develop a questionnaire. However, health utility assessments need to be repeated continuously. In certain human health emergencies, the use of some vaccines has been allowed without patent royalties having to be paid[38]. Commercial companies that own the rights to health assessments should reconsider their policies regarding their use.

CONCLUSlON

Health assessments that allow free registration would be useful for evaluating health utility in patients with liver disease. Alternatively, a portable QOL tracker could be used to perform QOL evaluations of any patient-reported outcome, and we are currently developing such a tracker.

Figure 2 Short from-36: Compensated liver cirrhosis vs sustained virologic response. A: Physical function; B: Role physical; C: Body pain; D:General health; E: Vitality; F: Social function; G: Role emotional; H: Mental health.

Figure 3 Health Utilities lndex-Mark2 or 3: Hepatitis C vs hepatitis B. HUI: Health Utilities Index.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Sandy Tan and Miyako Nara for their valuable discussions and help in preparing this manuscript.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Ishinuki T and Ota S conceptualized and designed the review; Ishinuki T, Harada K,Kawamoto M, and Meguro M searched for and screened the articles; Kutomi G, Tatsumi H, Harada K, and Kato T assessed the articles for eligibility; Miyanishi K and Ohyanagi T carried out the statistical analyses; Hui TT and Mizuguchi T drafted the initial manuscript; Mizuguchi T finalized the manuscript; and all of the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Supported byGrants-in-Aid from JSPS KAKENHI, No. JP 20K10404 (to Mizuguchi T) and No. JP 21K10715 (to Ishinuki T); the Hokkaido Hepatitis B Litigation Orange Fund, No. 2059198 (to Mizuguchi T) and No. 2136589 (to Harada K); Terumo Life Science Foundation, No. 2000666; Pfizer Health Research Foundation, No. 2000777; the Viral Hepatitis Research Foundation of Japan, No. 3039838; Project Mirai Cancer Research Grants, No. 202110251;Takahashi Industrial and Economic Research Foundation, No. 12-003-106; Daiichi Sankyo Company, No. 2109540;Shionogi and Co., No. 2109493; MSD, No. 2099412; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, No. 2000555; Sapporo Doto Hospital, No. 2039118; Noguchi Hospital, No. 2029083; Doki-kai Tomakomai Hospital, No. 2059203; Tsuchida Hospital, No. 2000092; Shinyu-kai Noguchi Hospital, No. 2029083 (to Mizuguchi T); and the Yasuda Medical Foundation, No. 28-1 (to Ishinuki T).

Conflict-of-interest statement:All authors have nothing to disclose.

PRlSMA 2009 Checklist statement:The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Japan

ORClD number:Tomohiro Ishinuki 0000-0003-3225-9781; Shigenori Ota 0000-0003-3123-9172; Kohei Harada 0000-0002-3245-6980; Masaki Kawamoto 0000-0002-2800-6207; Makoto Meguro 0000-0002-9170-6919; Goro Kutomi 0000-0003-4557-5126; Hiroomi Tatsumi 0000-0002-9688-6154; Keisuke Harada 0000-0002-7497-6191; Koji Miyanishi 0000-0002-6466-3458;Toru Kato 0000-0002-8520-1949; Toshio Ohyanagi 0000-0001-8335-3087; Thomas T Hui 0000-0003-2717-3983; Toru Mizuguchi 0000-0002-8225-7461.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies:The Japanese Society of Gastroenterology.

S-Editor:Ma YJ

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Ma YJ

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年31期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年31期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Duodenal-jejunal bypass reduces serum ceramides via inhibiting intestinal bile acid-farnesoid X receptor pathway

- Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography-based radiomics model for overall survival prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Prevalence and clinical characteristics of autoimmune liver disease in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and acute decompensation in China

- Application of computed tomography-based radiomics in differential diagnosis of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma at the esophagogastric junction

- Radiomics and nomogram of magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion in small hepatocellular carcinoma

- Insights into induction of the immune response by the hepatitis B vaccine