Urinary cystatin C:pediatric reference intervals and comparative assessment as a biomarker of renal injury among children in the regions with high burden of CKDu in Sri Lanka

Patabandi Maddumage Mihiri Ayesha Sandamini·Pallage Mangala Chathura Surendra De Silva ·Thibbotuwa Deniya Kankanamge Sameera Chathuranga Gunasekara·Sakuntha Dewaka Gunarathna ·Ranawake Arachchige Isini Pinipa·Chula Herath·Sudheera Sammanthi Jayasinghe ·Ediriweera Patabandi Saman Chandana·Nishad Jayasundara

Abstract Background Cystatin C (Cys-C) is an emerging biomarker of renal diseases and its clinical use,particularly for screening the communities affected by chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu),is hindered due to the lack of reference intervals (RIs) for diverse ethnic and age groups.The present study aimed to define RIs for urinary Cys-C (uCys-C) for a healthy pediatric population in Sri Lanka and in turn compare the renal function of the residential children in CKDu endemic and non-endemic regions in Sri Lanka.Methods A cross-sectional study was conducted with 850 healthy children (10–17 years) from selected locations for reference interval establishment,while a total of 892 children were recruited for the comparative study.Urine samples were collected and analyzed for Cys-C,creatinine (Cr) and albumin.Cr-adjusted uCys-C levels were partitioned by age,and RIs were determined with quantile regression (2.5th,50th and 97.5th quantiles) at 90% confidence interval.Results The range of median RIs for uCys-C in healthy children was 45.94–64.44 ng/mg Cr for boys and 53.58–69.97 ng/mg Cr for girls.The median (interquartile range) uCys-C levels of children in the CKDu endemic and non-endemic regions were 58.18 (21.8–141.9) and 58.31 (23.9–155.3) ng/mg Cr with no significant difference (P =0.781).A significant variation of uCys-C was noted in the children across age.Conclusions Notably high uCys-C levels were observed in children with elevated proteinuria.Thus,uCys-C could be a potential biomarker in identifying communities at high risk of CKDu susceptibility.

Keywords Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology·Cystatin C·Pediatric·Reference intervals·Renal injury ·Urinary albumin–creatinine ratio

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology (CKDu) is a critical global health concern that claims a number of lives every year [1].Although several underlying causes have been discussed,the exact etiology of the disease is still uncertain.Importantly,multiple studies indicate that the pediatric populations in CKDu endemic regions may express early indications of kidney dysfunction [2–4],that may be linked with incidence of CKDu in later life [5].Therefore,a comprehensive assessment of renal health of adolescents and pre-adolescents along with potential risk factors,is critical for early diagnosis of disease susceptibilities,identification of vulnerable communities and to develop better disease management strategies [2,6].

Commonly used conventional markers of renal function,such as serum creatinine (SCr),albuminuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR),may lack adequate sensitivity and specificity,in the early detection of abnormal kidney function,due to the non-proteinuric nature of the disease without detectable changes in these conventional markers in early stages [7–11].Particularly,in the case of children,SCr may not be adequately reliable and specific in identification of renal injury [12].Importantly,due to certain practical limitations associated with serum-based biomarkers,more sensitive,specific and noninvasive urinary biomarkers are preferably sought for assessing renal function in children.

Cystatin C (Cys-C) has been approved as a diagnostic biomarker of renal injury by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2018 [13].It is a small protein molecule (13 kDa) with a single non-glycosylated polypeptide chain consisting of 120 amino acid residues [14].The low molecular weight of Cys-C allows its easy filtration at the glomerulus [15].Cys-C has a constant production rate in the body as it is being secreted from all nucleated cells [7].Cys-C in circulation is eliminated by glomerular filtration and subsequently it undergoes complete tubular reabsorption and catabolism without tubular secretion.Hence,Cys-C is not normally found in urine in significant amounts [16].Further,as implied by the recent findings elevated levels of urinary Cys-C (uCys-C) may reflect tubular dysfunction and tubulo-interstitial disease [17].Previous research findings indicated that serum Cys-C is not only a more sensitive marker for CKDu but also a specific marker for the diagnosis of renal tubular damage particularly in the adults [18–20].In addition,studies have shown Cys-C to be a good predictor of acute kidney injury (AKI) in pediatrics and adults[21].Initial renal injury leads to AKI that is associated with significant morbidities and contributes the development of CKD in the absence of preventive interventions [22].Hence,precise characterization of early renal injury becomes vitally important in the management of both AKI and CKD.In contrast to serum-based markers,uCys-C is advantageous as a noninvasive marker of renal injury in screening vulnerable communities,particularly children.However,the main hindrance for the implementation of uCys-C in clinical practice is the lack of validated reference intervals for healthy pediatric populations.The reference intervals referred for adults may not be precisely applicable for children due to certain changes in renal physiology in children during growth and with advancing age [23].Importantly,certain non-occupational environmental risk factors including contaminated food and water with nephrotoxic substances are known to be potential drivers of CKDu in global hotspots[24].Thus,exposure to these risk factors may lead early renal damage in children,particularly in the areas with high burden of CKDu.According to recent studies,it is evident the prevalence of early renal injury among school-age children in regions with high burden of CKDu in Sri Lanka[2],Nicaragua [3,4],El Salvador [25] and Mexico [26].However,early detection of susceptibilities of renal injury requires diagnostic approaches with more sensitive and specific biomarkers of renal injury.Hence,to implement uCys-C as a potential diagnostic marker,the primary objective of the present study was to setup reference intervals of uCys-C for healthy children in Sri Lanka.The secondary objective was to comparatively assess the renal function of the residential children in CKDu endemic and non-endemic regions in Sri Lanka.Further,it was also aimed to investigate the associations of uCys-C with conventional marker,urinary albumin–creatinine ratio (UACR) [27–29] with several other variables including age,gender and body mass index (BMI)to develop detailed insights into the renal health of a pediatric population in rural Sri Lanka.

Methods

Study participants

Determination of reference intervals

The sample size for establishment of reference intervals was determined based on the formula derived by Bellera and Hanley (2007) for estimation of reference limits with regression-based methods [30].Assuming the uniform distribution of the covariate,a sample size of 837 produced a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) of a 95% reference limit with a width of only 8% of the width of a 95% reference interval.Including the dropouts,a total of 880 healthy children from 10 to 17 years of age at the time of sample collection,were recruited from government schools in CKDu endemic and non-endemic regions in Sri Lanka,in adherence to a multi-stage stratified proportionate random sampling approach.Participants with previous or persistent medical complications including renal,respiratory,and metabolic disorders,known genetic disorders,family history of chronic kidney disease,BMI in the unhealthy range;underweight (<18.5 kg/m 2),overweight (23–24.9 kg/m 2)and obese (>25 kg/m 2) [31],and those who were taking medications for any form of medical complications were excluded from the analysis to enhance the probability of getting data of healthy individuals for setting up reference intervals.After application of above exclusion criteria,860 boys and girls were recruited for further analysis.Furthermore,10 individuals were also excluded due to the presence of microalbuminuria (UACR >30 mg/g).Hence,biomarker data from 850 (boys:400;girls:450) were used for the establishment of reference intervals.

Comparison of renal function of the residential children in CKDu endemic and non-endemic areas

The second phase of the study was conducted with total 892 children from seven selected locations representing different climatic zones and prevalence of CKDu cases.Three locations were selected representing CKDu endemic regions;Ambagaswewa in Polonnaruwa District,Padavi Jayanthipura and Lassanagama in Trincomalee district in the dry zone,Sri Lanka.The regions with highest incidence of CKDu cases were selected as CKDu endemic regions based on the prevalence of CKDu in Sri Lanka.Four locations were selected as CKDu non-endemic regions representing both dry and wet zones.Two locations,Tissapura and Dematamalpelassa were selected from regions with emerging evidence of CKDu in Ampara district (dry zone)while the other two locations Kolambageara and Sevanagala were selected from Rathnapura (wet zone) and Monaragala (intermediate zone) districts,respectively.Sample size was calculated using the formula;n=[(z 2) P (1–P)]/d 2 .The standard normal variate (z 2) was taken as 1.96 at 5% type 1 error (P<0.05) and the absolute error (d) was assumed to be 3% (d=0.03) [32].The prevalence of abnormal renal function (P),as indicated by moderately and highly elevated UACR among the children in CKDu endemic regions in Sri Lanka,was considered as 8.7% (P=0.087) based on the previous study conducted by Agampodi et al.in 2018[2].Accordingly,the estimated minimum sample size was 340 for the CKDu endemic region and the same size of sample was taken from CKDu non-endemic regions for comparison.A multi-stage stratified proportionate random sampling approach was adopted for selection of schools and children in CKDu endemic and non-endemic regions.For the baseline screening session,the total participation was 892 children (10–17 years of age);421 from CKDu endemic regions and 471 from CKDu non-endemic regions.

Management of samples and data

A fresh non-fasting,first void morning urine sample was obtained into a sterile container.Following collection,each sample was immediately stored at 4 °C and during the transit to the laboratory.Urine samples were centrifuged at 1000 RCF for 15 minutes at 4 °C and the supernatant of each sample was stored at –80 °C until further analysis for creatinine,albumin and Cys-C.Sample analysis was done in the Biochemistry laboratory of the Department of Zoology,Faculty of Science,University of Ruhuna,Matara,Sri Lanka.An interviewer-administered structured questionnaire was used to gather data on lifestyle patterns,present health status,and medical history along with demographic data from the participants.

Assessment of cystatin C

Determination of Cys-C concentrations in urine samples was performed using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with assay kits (CUSABIO,P.R.China;cat no:CSB-E08384h) according to the manufacturer’s assay protocol.The intra-assay precision was (CV% <8%) while the inter-assay precision was (CV% <10%).Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer(Epoch 2,Biotek Instruments,USA).

Determination of creatinine and micro-albumin in urine

Biochemical analysis of urine samples for creatinine and micro-albumin was done using an automated biochemistry analyzer (Humastar 100,Human GmbH,and Germany).Creatinine assay was based on Jaffe reaction while microalbumin assay was based on Particle Enhanced Turbidimetric Inhibition Immuno Assay (PETINIA).

Statistical analysis

For the reference interval establishment

uCys-C concentrations were adjusted for urinary creatinine before analysis.We identified near log-normal distribution in uCys-C data;therefore,according to the guidelines of International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) for determination of reference limits [33],a non-parametric approach was adopted for data analysis.

The uCys-C values of the individuals with elevated UACR (>30 mg/g) were excluded from the data set for determination of reference intervals.The data were analyzed for outliers and according to Tukey’s method,outliers were identified and removed [34].The data were stratified according to age and partitioned based on gender before the analysis.To compare the uCys-C levels of children in the same age range from different locations and variation of uCys-C levels among different age groups,Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test was performed [35].As the uCys-C concentrations showed no significant difference among the participants from different locations,the data were processed as single data set.There was no significant difference in uCys-C concentrations between boys and girls according to the of Mann–WhitneyUtest.Quantile regression was applied for the determination of reference intervals for creatinine-adjusted uCys-C concentrations.Reference intervals at 2.5th,50th and 97.5th quantiles were expressed with 90% CIs for each age group partitioned by gender [12].

For the assessment of the renal function of the residential children in CKDu endemic and non-endemic areas

The concentrations of uCys-C in each urine sample were normalized to its creatinine content prior to further analysis.Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine the distribution pattern of creatinine-adjusted uCys-C concentrations for endemic and non-endemic groups separately.Since the distributions of data followed lognormal distribution,a nonparametric statistical approach was adopted.Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test was used for comparison of creatinine-adjusted uCys-C concentrations in children in different age groups from endemic and non-endemic regions.

Mann–WhitneyUtest was performed to compare uCys-C and UACR levels of the study groups from endemic and nonendemic regions.Spearman’s correlation test was performed to identify the associations of uCys-C with UACR for both groups.Further,the associations of uCys-C and UACR with age,gender and BMI were also identified using Spearman’s correlation analysis.

Statistical analysis and data presentations were performed using Stata MP 1.0 (Stata Corp LLC,USA),IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM INC.,USA) and GraphPad Prism 9.0(GraphPad Software LLC,USA).

Ethical considerations

The present study was conducted under the approval of the Ethics Review Committee of the Faculty of Medicine,University of Ruhuna,Sri Lanka [ref.no.2020.P.124(20.11.2020)].School authorities and children from all selected schools were made aware of the study with information sheets and personal communications.Written consent was obtained from the parents or guardians on behalf of the children involved in the study along with their ascent for participation.The participants granted consent for the provision of data and samples,sample analysis and storage,and use of results for publications.The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Reference interval assessment

From the total recruitment of 880 participants from rural regions in Sri Lanka,a total of 850 (boys:400;girls:450)healthy children met the inclusion criteria for the study.The mean age of the study population was 14.32 (standard deviation:1.07) years.

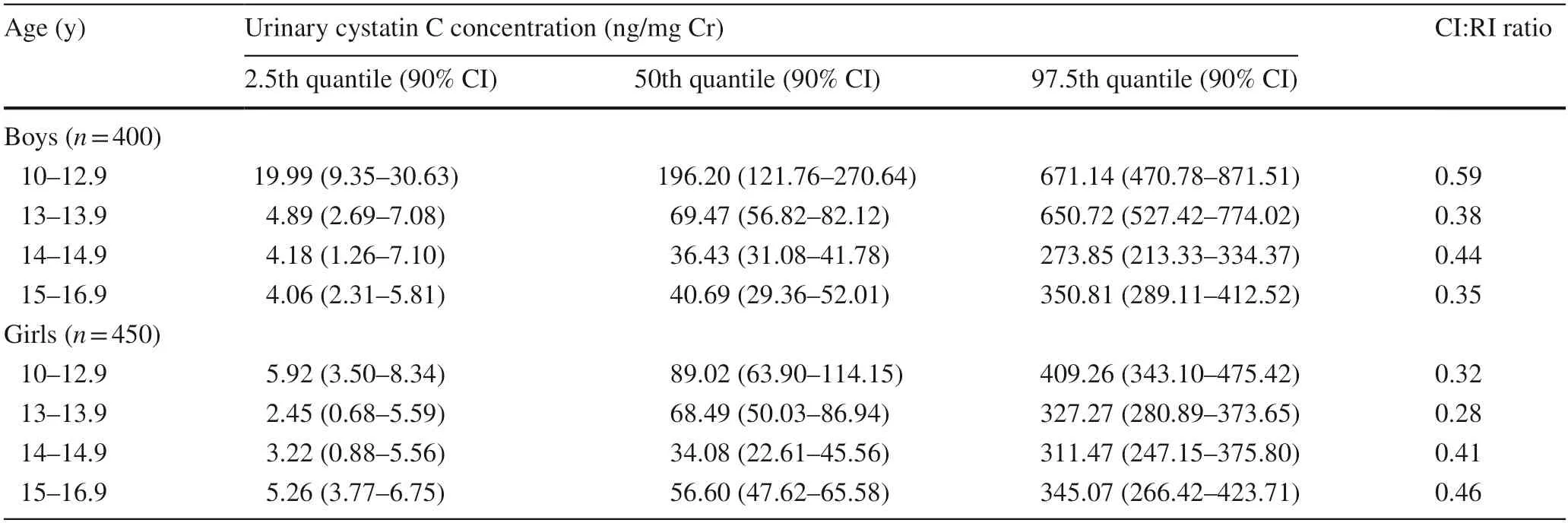

Reference intervals for uCys-C were defined for boys and girls separately by age stratification.The 95% reference intervals for uCys-C (2.5th and 97.5th quantiles) along with median (50th quantile) and the 90% CIs were determined using the quantile regression method (Table 1).

Table 1 Reference intervals and confidence intervals for creatinine-adjusted urinary cystatin C levels for healthy children

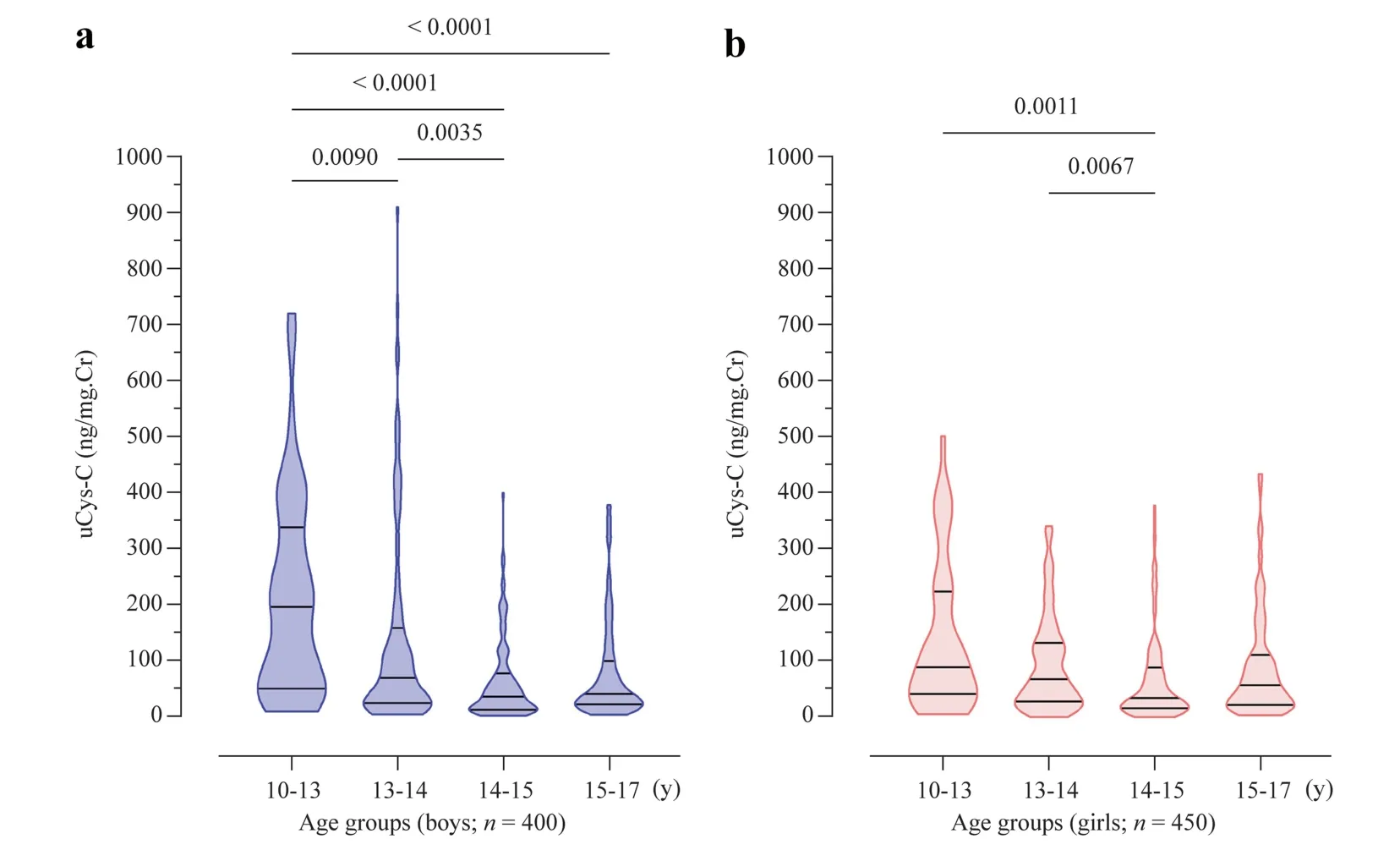

There was no significant difference in uCys-C concentrations between boys and girls in the study groups (P=0.169).Moreover,significant differences in uCys-C levels were identified among the age groups within a given gender.The distribution of uCys-C in boys and girls across the age is shown in Fig.1.

Fig.1 Age-stratified distribution of uCys-C in children.Graphs illustrate the median and interquartile range.Inter-group statistical significance is expressed as implied by Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test.a Boys; b girls.uCys-C urinary cystatin C,Cr creatinine

In Spearman’s correlation analysis,uCys-C showed weak associations with UACR (r=0.01;P<0.0001),BMI (r=–0.07;P=0.04) and age (r=–0.13;P<0.0001)irrespective of gender.In gender-specific analysis,uCys-C concentrations of both boys and girls showed weakassociations with UACR (r=0.39 for boys andr=0.29 for girls;P<0.0001) while uCys-C concentrations showed significant associations with age (r=–0.21;P<0.0001)and BMI (r=–0.12;P=0.03) only in boys.Significantly high incidence (P<0.0001) of family history of CKDu was noted in CKDu endemic regions compared to the CKDu non-endemic regions.

Assessment of renal function of the residential children in CKDu endemic and non-endemic areas

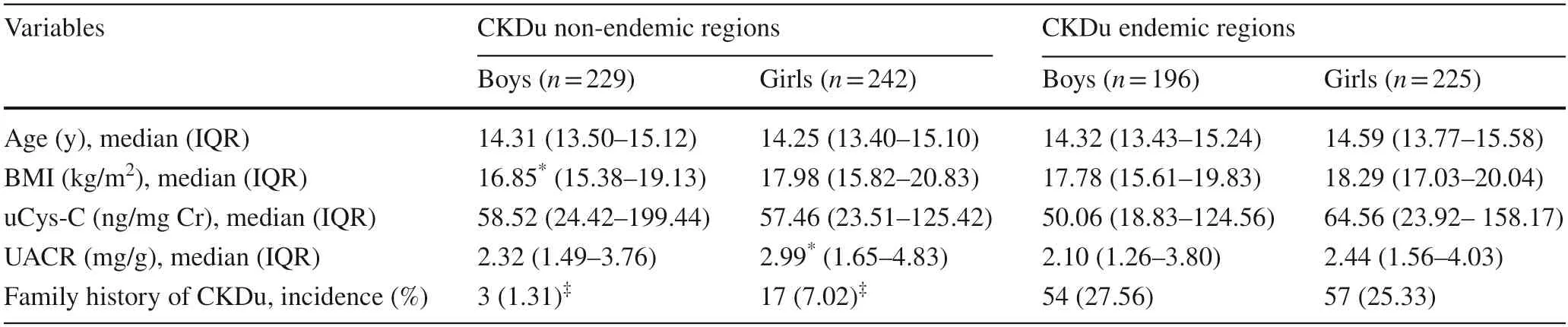

A total of 892 participants who met the selection criteria were recruited to compare differences in renal function between participants from CKDu non-endemic (n=471)and CKDu endemic (n=421) regions.The summary of the distribution of age,BMI,uCys-C and UACR in both cohorts is displayed in Table 2.

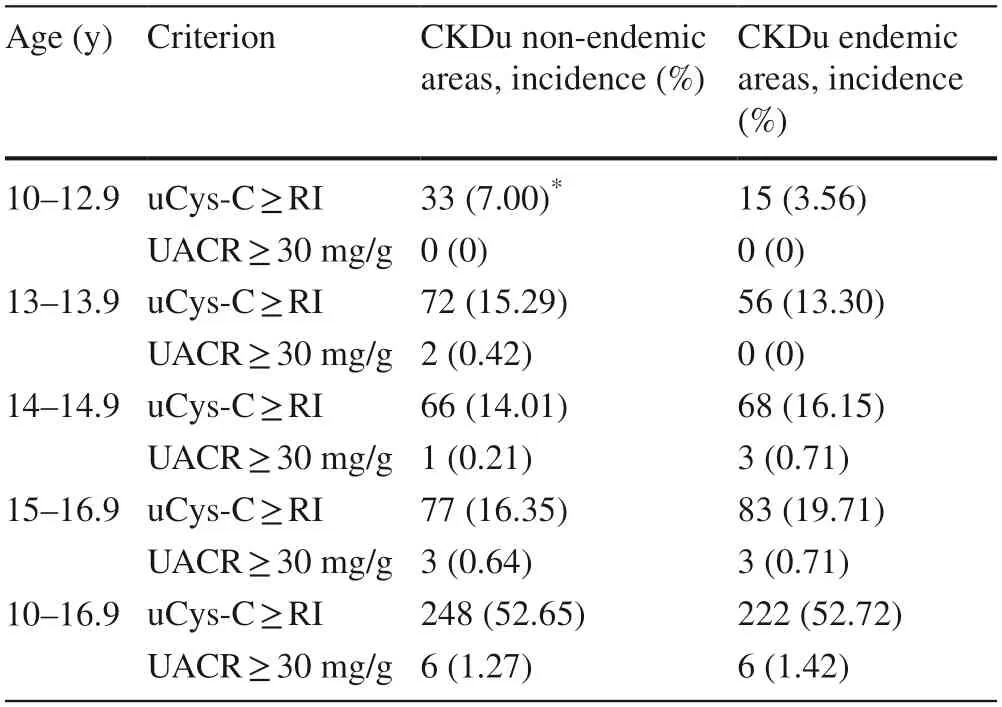

According to the calculated reference intervals for the uCys-C concentrations of participants across different age groups,the number of children who had uCys-C levels above median reference interval (50th quantile) and children who had elevated UACR (>30 mg/g) were identified and the incidence is given in Table 3.

Table 2 Creatinine-adjusted urinary cystatin C concentrations,UACR,age and BMI in CKDu non-endemic cohort and CKDu endemic groups

Table 3 The incidence of elevated urinary cystatin level above the median reference value (50th quantile) and urinary ACR value above low-risk limit (30 mg/g) in study participants from CKDu endemic and non-endemic regions

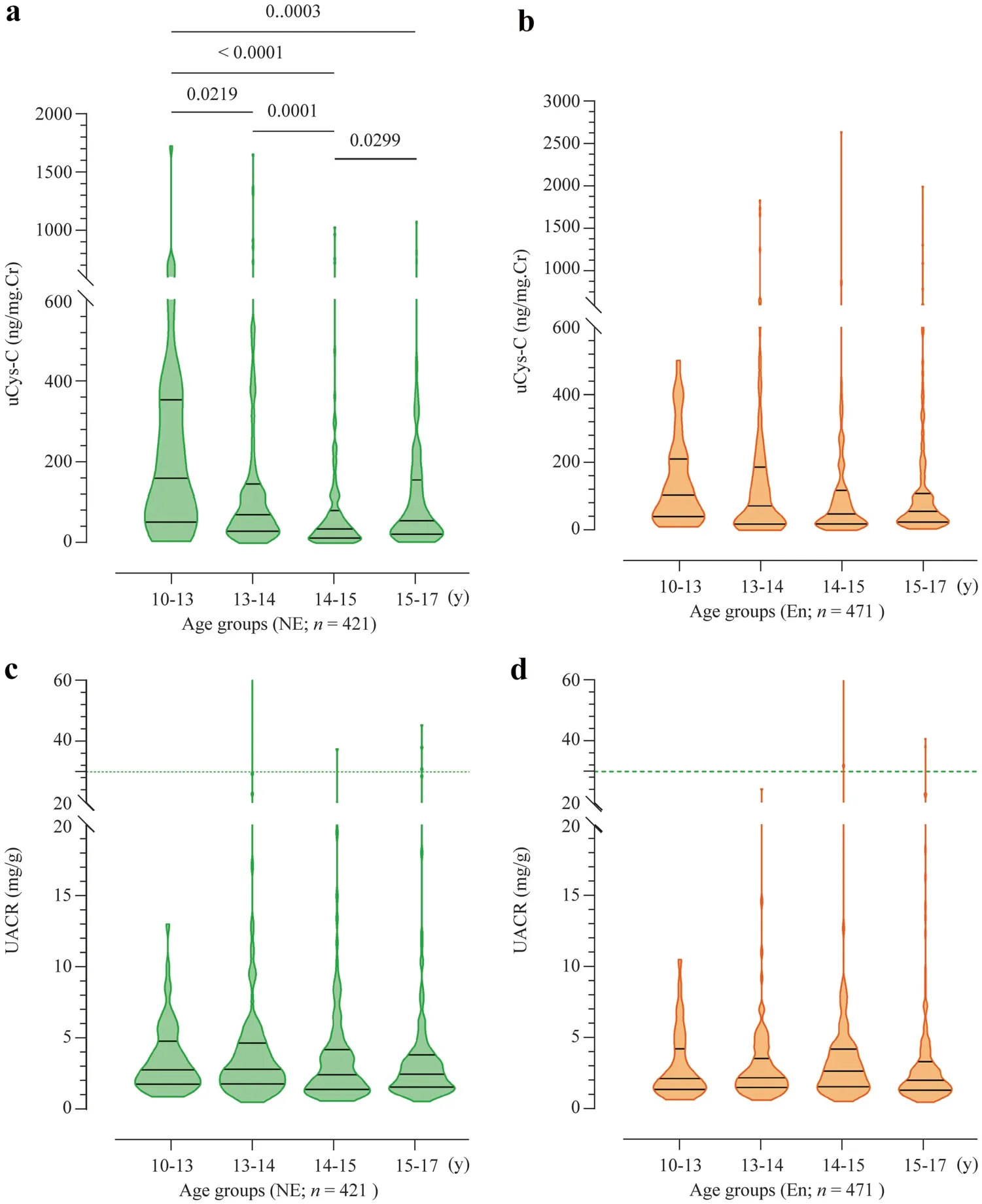

uCys-C levels showed no significant difference between the study participants in CKDu endemic and non-endemic regions when stratified based on age or gender.Notably,uCys-C is statistically significant (P<0.05) between age groups in the CKDu non-endemic group,but such a relationship was not evident among the study participants from the CKDu endemic regions The distributions of uCys-C levels and UACR in children from CKDu endemic and nonendemic regions are shown comparatively in Fig.2.

Fig.2 Age-stratified distribution of clinical parameters in children from CKDu endemic (En) and non-endemic (NE) regions.Graphs illustrate the median and interquartile range.a uCys-C levels in children from CKDu NE regions; b uCys-C levels in children from CKDu En regions; c UACR levels in children from CKDu NE regions; d UACR levels in children from CKDu En regions.Intergroup statistical significance is expressed as implied by Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test.uCys-C urinary cystatin C,CKDu chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology,UACR urinary albumin–creatinine ratio,Cr creatinine

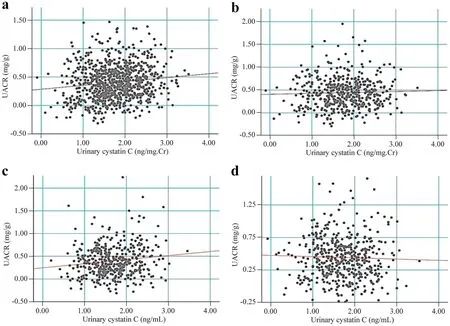

In Spearman’s correlation analysis,uCys-C levels of children in the CKDu endemic group showed a significant positive correlation with UACR values.This correlation was also identified in CKDu endemic group between UACR and uCys-C,when uCys-C was not adjusted for creatinine levels.Further,no significant association of uCys-C was detected with age,gender or BMI was detected in CKDu endemic cohort.In contrast,in the CKDu non-endemic cohort,there was a significant weak correlation between uCys-C and age (Rs=–0.185;P<0.0001) while no significant association with gender,BMI and UACR was identified.The associations of uCys-C with UACR for the children in CKDu endemic and non-endemic groups are illustrated in Fig.3.

Fig.3 Association of UACR with (a,b) or without (c,d) creatinine-adjusted urinary cystatin C levels in study participants as implied by Spearman’s correlation analysis.a Children in CKDu endemic regions (correlation coefficient; R s =0.245,P <0.05);b children in CKDu non-endemic regions (R s =0.032,P =0.489);c children in CKDu endemic regions (correlation coefficient;R s =0.136,P <0.01); d children in CKDu non-endemic regions(R s =–0.032,P =0.490).UACR urinary albumin–creatinine ratio,CKDu chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology,Cr creatinine

The ACR level (mean ± standard error of mean) of children from CKDu endemic region was (5.263 ± 1.404) mg/g and(4.558 ± 0.626) mg/g indicating a significant difference across the region (P=0.009).Additionally,significant,but weak positive correlations were identified between UACR and gender in CKDu endemic (Rs=0.099,P=0.042) and non-endemic(Rs=0.144,P=0.002).The median (interquartile range,IQR)uCys-C levels of children from CKDu endemic regions was 58.18 (21.80–141.90) ng/mg Cr and 57.46 (23.81–152.3) ng/mg Cr indicating no significant difference (P=0.823) across the region of residency.Further,the median (IQR) uCys-C level of the children with high albuminuria (ACR ≥ 30 mg/g)was high [107.3 (59.02–197.3) ng/mg Cr] in comparison to the uCys-C level [56.72 (22.73–146.7) ng/mg Cr] of the children with low albuminuria (ACR <30 mg/g) while the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.158).However,this may imply certain utility of uCys-C in diagnosing renal injury and it requires further validation with detailed studies.

Discussion

In the present study,we sought to determine reference intervals for uCys-C for a healthy pediatric population within the age range of 10–17 years from the dry zone in Sri Lanka.Subsequently,we compared differences in uCys-C and UACR levels between regions impacted by CKDu and regions with little CKDu prevalence.

Our study on the reference population did not identify a significant relationship between uCys-C concentrations in boys and girls.However,reference intervals were calculated for boys and girls separately as in previous studies [34,36].Further,when assessed based on regions of residency,uCys-C levels showed no significant variation across the regions.Hence,the data were evaluated as a single group for the establishment of the reference intervals.

The range of median reference intervals (50th quantile)we observed here for uCys-C was 45.94–64.44 ng/mg Cr for boys and 53.58–69.97 ng/mg Cr for girls within the age range of 10–17 years.Nonetheless,the uCys-C values are consistent with the values reported in the studies with pediatric communities in the same age range from different countries.Madsen et al.reported a median value of 99.5 ng/mg Cr (range:13.5–215.6 ng/mg Cr) for healthy boys and girls within the age range of 3–15 years [7].In our study,the mean uCys-C level was 81.98 ng/mL while 95% CIs were (74.18–89.77) ng/mL and the values are consistent with the findings of the above studies.However,adjustment of urinary biomarkers for urinary creatinine,particularly for setting up reference intervals,may be more reliable as biomarker concentrations in urine is likely variable due to several factors (e.g.,level of hydration,sample collection time and urine output) [2].

A striking result in our analysis is the finding that compared to the CKDu non-endemic population,CKDu endemic participants showed reduced variability in uCys-C across different age groups (Figs.1,2 a,and b).Recent studies have shown that several kidney biomarkers including albumin,β2-microglobulin,neutrophil gelatinaseassociated lipocalin,SCr and serum Cys-C are expressed at varying degrees in early life [34,37].However,no published data could be found for the variability of uCys-C with different age groups in healthy pediatric populations.In the present study we have identified the variation of uCys-C at different age levels of our pediatric populations.Our findings show that uCys-C concentrations exhibit no specific pattern till approximately 13 years of age and then tends increase from 14 to 17 years of age.Studies show that in the transitional age individuals start to produce higher levels of Cys-C and the peak production of Cys-C is observed after 13 years of age that remains stable until age 50 [6,37].

Our findings also suggested that the non-endemic individuals in transitional age (around 10–13 years),uCys-C is highly variable in the 10–14 age categories and attain some kind of stability as the age increases to adolescents age (about 14–17 years).The lack of such a trend in CKDu endemic population coupled to the significant positive relationship that was identified between uCys-C and UACR in the CKDu endemic cohort (r=0.245,P<0.01)indicates a unique uCys-C phenotype in CKDu endemic pediatric populations.The differences between CKDu endemic and non-endemic urinary markers are further reflected in the percent distribution of participants with uCys-C and UACR values that differ from the reference interval values.For example,the percentage distribution of children with above reference level uCys-C and UACRvalues increased in CKDu endemic cohorts with increasing age,while the opposite was true for the non-endemic cohort.

We have several strengths in our study that are worth to be mentioned here.According to the guidelines of the IFCC,the minimum number of subjects required for setting up reference intervals is referred to as 120 [33].In the present study,we reached this criterion with a total of 880 healthy individuals in the study group.However,recruitment of a higher number of candidates,may enhance the accuracy and reliability of the reference limits in the study [33,38].For establishment of reference intervals,we attempted our best to select healthy children.For ensuring that,we selected children with no records of current or previous medical complications including urinary disorders and receive no medications.Further,BMI in normal range,and absence of family history of CKD/CKDu,were also considered as enrolment criteria.Then we have prioritized the children in the dry zone for the assessment of renal function,as the prevalence CKDu is highly associated with dry zone agricultural lifestyle,and the children in these communities are more vulnerable for renal diseases.This is the other main strength of our study.

There were also several noteworthy limitations in our study.As there were no established cutoffvalues for uCys-C to distinguish renal injury,we used elevated UACR(≥ 30 mg/g) as the main criteria to characterize abnormal renal function in children.In this consideration,the number of cases with elevated UACR (≥ 30 mg/g) was not satisfactory enough in comparison to the number of children with UACR below 30 mg/g to determine cutoffvalues for uCys-C with acceptable sensitivity and specificity.To understand the renal function better,it still requires conventional markers of renal function,such as SCr and eGFR.However,due to certain practical limitations in venesection with children,we did not assess serum-based markers in the present study,hence SCr and eGFR data for the children are not presented.Although our main focus was noninvasive urinary markers in the present study,incorporation of these data may contribute better assessment of renal function with CKD staging.The present study was a cross-sectional study and did not evaluate renal function in repeated measures to identify persistent renal damage and progression of renal injury towards chronic conditions.Considering the receiver operator characteristic analysis to define cutoffvalues for uCys-C to predict the outcome of elevated albuminuria,the number of children with high albuminuria was very low compared to the number of children with normal albuminuria.Hence,we could not achieve cutoffvalues for uCys-C to predict the outcomes of abnormal renal function in the present study.Further,the main focus of the study is children within the age range of 10–17 years and it does not interpret the renal function of children below 10 years of age.However,a cohort study with increased sample size and wider age range,with progressive assessment of renal function may contribute better accuracy in making conclusions about the prevalence of altered renal function among children particularly from CKDu endemic regions.

In conclusion,our study suggested that the uCys-C may be an early diagnosis marker for children in the adolescent age range,and potentially it may not be appropriate for early ages.To our knowledge,this is the first study to establish age-appropriate reference intervals for uCys-C levels in a pediatric population from a rural and socioeconomically underprivileged region in Sri Lanka.Due to certain practical limitations,serum-based evaluations are not favorable for pediatric populations.Hence,urinary biomarkers such as Cys-C,appear to be noninvasive and convenient in assessment of renal function.Although statistical significance was not achieved due to high degree of variability of uCys-C in children,some notable differences were identified between child groups from CKDu endemic and non-endemic regions.Particularly,based on elevated albuminuria (UACR ≥ 30 mg/g),the prevalence of abnormal renal function among the children in CKDu endemic regions (1.42%) and non-endemic areas (1.27%) was not statistically significant.However,the median uCys-C levels in children with elevated albuminuria (UACR ≥ 30 mg/g) were high in comparison to the uCys-C level of the children with low albuminuria(ACR <30 mg/g) while the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.158).Thus,this may suggest that uCys-C may be a potentially applicable biomarker for early detection of renal injury in children.To the extent of findings from pediatric studies and the present study,the prevalence of altered renal function is evident among children particularly in regions affected by CKDu.As CKD/CKDu is an ultimate outcome of progressive renal injury,detection of renal damage or susceptibilities is critically important in disease management.To achieve this,it requires sensitive,specific and noninvasive markers over the conventional clinical markers.Shedding light upon this clinical approach,our study has revealed potential utility of uCys-C in characterization of early renal injury in children.If further validation is done with detailed studies,uCys-C could be integrated into clinical decision making for pediatric populations to characterize the early renal damage and effective interventions in management of renal diseases.Further,validation of uCys-C as a biomarker of renal injury,particularly glomerular dysfunction,may be advantageous in identifying communities at high risk of kidney disease susceptibility.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank all the participants children who participated in the study,parents,academic and nonacademic staff members of the schools,government authorities school principals,teachers,and parents for their valuable support.

Author contributionsSPMMA contributed to data curation,formal analysis,investigation,software,visualization,writing of the original draft,review and editing.DSPMCS contributed to conceptualization,data curation,formal analysis,funding acquisition,investigation,methodology,project administration,resources,software,supervision,validation,review and editing.GTDKSC contributed to data curation,formal analysis,investigation,software,visualization,writing of the original draft,review and editing.GSD contributed to data curation,formal analysis,and investigation.PRAI contributed to data curation and investigation.HC,JSS and CEPS contributed to resources,supervision,validation,review and editing.JN contributed to conceptualization,project administration,resources,supervision,validation,review and editing.

FundingThis research was funded by the Accelerating Higher Education Expansion and Development (AHEAD) Operation of the Ministry of Higher Education funded by the World Bank (No.AHEAD DOR 02/40).

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due restrictions under the approval of the ethics review board,but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approvalThe study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki,and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Faculty of Medicine,University of Ruhuna (reference no:2020.P.124;date:29.01.2021).Informed consent to participate in the study have been obtained from the children and their parents.

Conflict of interestNo financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.None of the authors was involved in the journal’s review of,or decisions related to,this manuscript.The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

World Journal of Pediatrics2022年3期

World Journal of Pediatrics2022年3期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Long-term physical,mental and social health effects of COVID-19 in the pediatric population:a scoping review

- Prediction modelling in the early detection of neonatal sepsis

- Maternal smoking status during pregnancy and low birth weight in offspring:systematic review and meta-analysis of 55 cohort studies published from 1986 to 2020

- Associations of early-life factors and indoor environmental exposure with asthma among children:a case–control study in Chongqing,China

- Handmade tri-leaflet ePTFE conduits versus homografts for right ventricular outflow tract reconstruction

- Occurrence of early epilepsy in children with traumatic brain injury:a retrospective study