A case of massive hemoptysis after radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial f ibrillation

Zhen Ren, Shu Li, Qing-bian Ma

Department of Emergency Medicine, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing 100191, China

Massive hemoptysis (MH) sometimes causes a fatal condition;thus, prompt diagnosis and treatment for MH are crucial. However, a wide range of diseases (e.g.,infectious diseases, malignancies, and systemic autoimmune diseases) is associated with the development of MH,which occasionally causes difficulty with identifying the specific etiology. The administering of drugs increases the difficulty,and MH may have other etiologies, such as conditions resulting from interventions.

The clinical management of atrial fibrillation (AF)consists of a multimodal approach, including medical,interventional, and surgical treatments.As a widely used intervention in the treatment of AF, radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) may introduce many complications.Pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS) is an underrecognized and often misdiagnosed syndrome associated with this procedure.However, the diagnosis and management of MH cases due to PVS have rarely been addressed.

A 41-year-old man presented to our emergency department (ED) with cough and hemoptysis. He had complained of hemoptysis 22 days before and had a history of AF. Four months ago, he had been hospitalized in a community hospital and undergone RFCA for AF. He had been taking dabigatran until 40 days before the onset of hemoptysis. His chest radiograph taken in our ED was unremarkable, but fibro-laryngoscopy revealed fresh blood stains in the posterior area of the epiglottis. The patient received azithromycin and hemostatic therapy medication with carbazochrome sodium sulfonate, hemocoagulase agkistrodon, and Yunnan white powder, but the treatment was ineffective. At the initial medical evaluation, his blood pressure was 118/74 mmHg (1 mmHg=0.133 kPa), heart rate 105 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute,and body temperature 36.7 °C. His oxygen saturation, when breathing room air, was 100%. Physical examination was generally normal, with no rales in the lungs or murmurs of the heart.

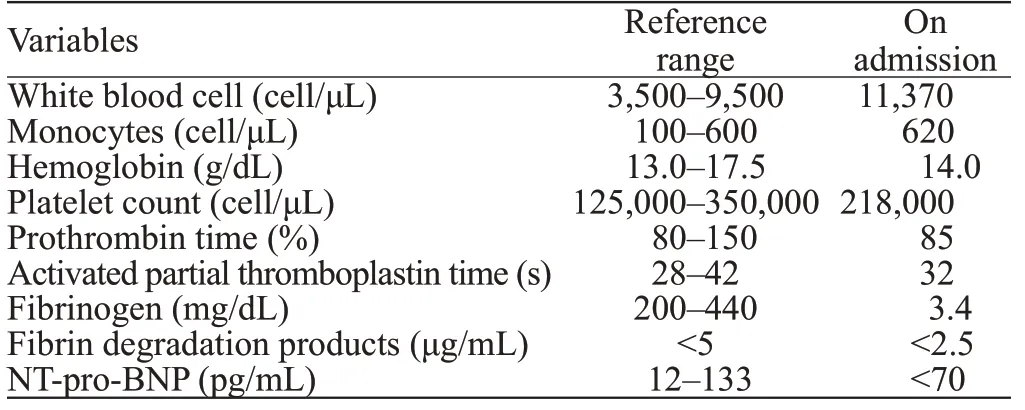

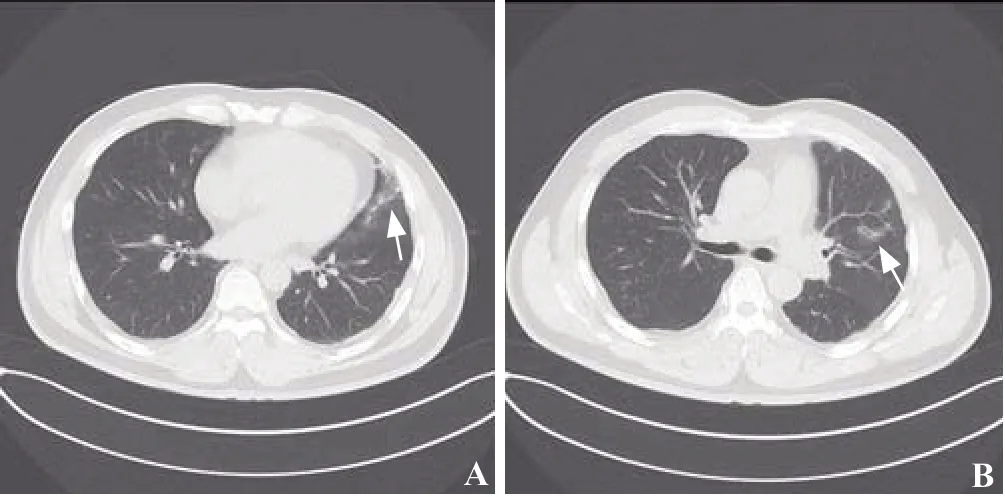

Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed scattered ground-glass opacities (GGOs) and patching effusions in the left upper lobe (Figures 1 A and B). Laboratory tests showed elevated white blood cells and monocytes (Table 1).The coagulation test was normal. An autoimmune panel was negative for the antinuclear antibody, anti-DNA antibody,anti-smooth muscle antibody, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. An infective workup was also negative for any cultures of beta-D-glucan and tuberculosis (TB).

Table 1. Laboratory data

Serial hemoglobin measurements revealed a progressive decline from 14 g/dL on admission to 11.7 g/dL the next day. Consequently, bronchial arteriography was performed,which showed no signif icant bronchial arterial hemorrhage,but suggested that the left bronchial artery was thickened and tortuous. The interventional radiologists decided to perform a bronchial artery embolization (BAE) on the left lobe suspected of culprit vessel with coils. Two hours after BAE,the patient developed another episode of MH (200 mL).

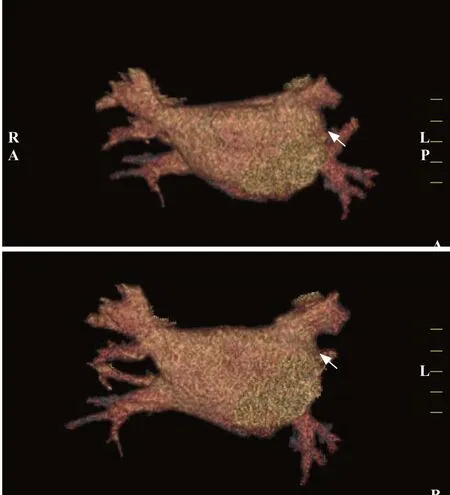

Taking the standard diagnostic approach, the bleeding source remained unexplained in the patient. Another possibility was that the hemoptysis and GGOs were caused by underlying cardiovascular diseases. However, this patient had no evidence of congestive heart failure, pulmonary edema, rheumatic heart disease, or pulmonary hypertension.Considering the medical history of RFCA 4 months ago,PVS was suspected. Contrast-enhanced multi-slice CT venography with three-dimensional reconstruction was conducted, which found left superior PVS (Figures 2 A and B). Pulmonary vein (PV) diameters (mean reference range)were reported as follows: right superior PV 20.5 mm (13.0-15.0 mm), left superior PV 13.8 mm (16.0-17.0 mm), right inferior PV 20.4 mm (16.0-17.0 mm), and left inferior PV 13.4 mm (14.0-15.0 mm). The f inal diagnosis was PVS post RFCA for AF.

Figure 1. Chest CT. Both f igures (A and B) revealed scattered GGOs and patching effusions (shown by arrows) in the left upper lobe. CT:computed tomography; GGOs: ground glass opacities.

Figure 2. Contrast-enhanced multi-slice CT venography with threedimensional reconstruction. Both figures (A and B) revealed detected left superior PVS (shown by arrows). CT: computed tomography; PVS:pulmonary venous stenosis.

Because the massive hemorrhage persisted, urgent surgical intervention was performed. During the surgical procedure, it was confirmed that the left superior PV and its branch wall were obviously thickened, and the lumen was almost occluded; the lumen of the left lower PV was enlarged, and its entrance to the atrium was significantly narrowed. Pericardial patch plasty restored the pulmonary venous drainage, veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) supported the patient’s breathing and circulation, and a temporary epicardial pacemaker provided cardiac pacing. On day 5 after surgery, the patient was successfully weaned offECMO. On postoperative day 7, the patient was extubated from the ventilator. On postoperative day 17, the patient was discharged with no event.

MH is rare, accounting for less than 1%-5% of all cases of hemoptysis.However, MH is life-threatening due to the influence of blood upon oxygen exchange.In geographical areas with a high incidence of TB, TB remains a common etiology of hemoptysis (24.8%).Otherwise,pulmonary malignancy (19.1%) is the most frequent cause of hemoptysis. Pneumonia (18.6%), bronchiectasis (14.9%),and acute bronchitis (13.7%) are frequent etiologies in developed countries.MH may have other etiologies, such as conditions resulting from interventions.

PVS is def ined as ≥20% luminal narrowing of PVs.Jin et alreported that when venous pressure suddenly rose for some reason, the venous dilatation or varicose formation caused by elevated pulmonary venous pressure may trigger rupture. Histological examination of PVS in patients after RFCA shows obviously thickened vein walls resulting in cardiomyocyte death followed by myof ibroblast proliferation.

This patient’s course highlighted three important clinical issues.

First, PVS after RFCA for AF might be an etiology of MH. PVS is an underrecognized syndrome that is a reported complication of RFCA in patients with AF; the published incidence of PVS varies widely from 0% to 38%.As a result, the diagnosis of PVS is often delayed. Emergency department (ED) physicians should be alert to surgical complications, especially for patients with newly developed respiratory symptoms after RFCA. Therefore, a detailed medical history and a complete physical examination may provide diagnostic information for the origin of a case of hemoptysis.

Second, according to the clinical condition of a patient’s MH, the appropriate examination should be chosen based on safety and efficiency. Especially in unstable MH, the primary focus is patient stabilization and resuscitation.The initial assessment should include complete laboratory tests and imaging.Multi-slice spiral chest CT angiography(MCTA) may be a noninvasive and useful examination to diagnose hemoptysis, localize bleeding, and detect potential vascular malformation.Hirshberg et alreported that bronchoscopy was another examination used to locate the bleeding spot with sufficient suction, and provided the possibility for endoscopic intervention. Unfortunately,during the COVID-19 pandemic, bronchoscopy has been underutilized due to conservative hospital policy. Yet, it is estimated that 90% of cases of MH emanate from the bronchial vascular system.Therefore, bronchial artery embolization (BAE) is now universally accepted as an effective and first-line treatment of MH, especially in the setting of failed noninvasive procedures.

Third, there are several therapeutic options to restore pulmonary venous drainage. Nonsurgical therapeutic options for management of patients include stent implantation and invasive balloon angioplasty.Currently, a percutaneous dilatation with balloon angioplasty of the narrowed PV represents the first-line therapy for symptomatic PVS. At long-term follow-up, stent implantation seems to be superior to balloon angioplasty alone.However, in an emergency situation, lobectomy or pneumonectomy could be a lifesaving procedure performed for acute MH or complete PV occlusion.Other surgical treatment options for patients with hemoptysis caused by acquired PVS include venoplasty or a pericardial patch plasty.

We report a case of MH caused by PVS after RFCA for AF. PVS should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with hemoptysis. In particular, patients with a history of interventional therapy for AF are predisposed to pulmonary venous obstruction. Contrast-enhanced multislice CT venography with three-dimensional reconstruction is an important method for the detection of PVS. Early diagnosis and reasonable treatment based on the patient’s condition can improve a patient prognosis.

None.

Not needed.

The authors have no conf lict of interest.

All authors have substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work;drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and f inal approval of the version to be published.

World Journal of Emergency Medicine2022年1期

World Journal of Emergency Medicine2022年1期

- World Journal of Emergency Medicine的其它文章

- Emergency department electric scooter injuries after the introduction of shared e-scooter services: A retrospective review of 3,331 cases

- Tranexamic acid for major trauma patients in Ireland

- A cadaveric model for transesophageal echocardiography transducer placement training: A pilot study

- Development of an intensive simulating training program in emergency medicine for medical students in China

- Changes and signif icance of serum troponin in trauma patients: A retrospective study in a level I trauma center

- Anemia and risk of periprocedural cerebral injury detected by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement