都锦生的锦绣江南

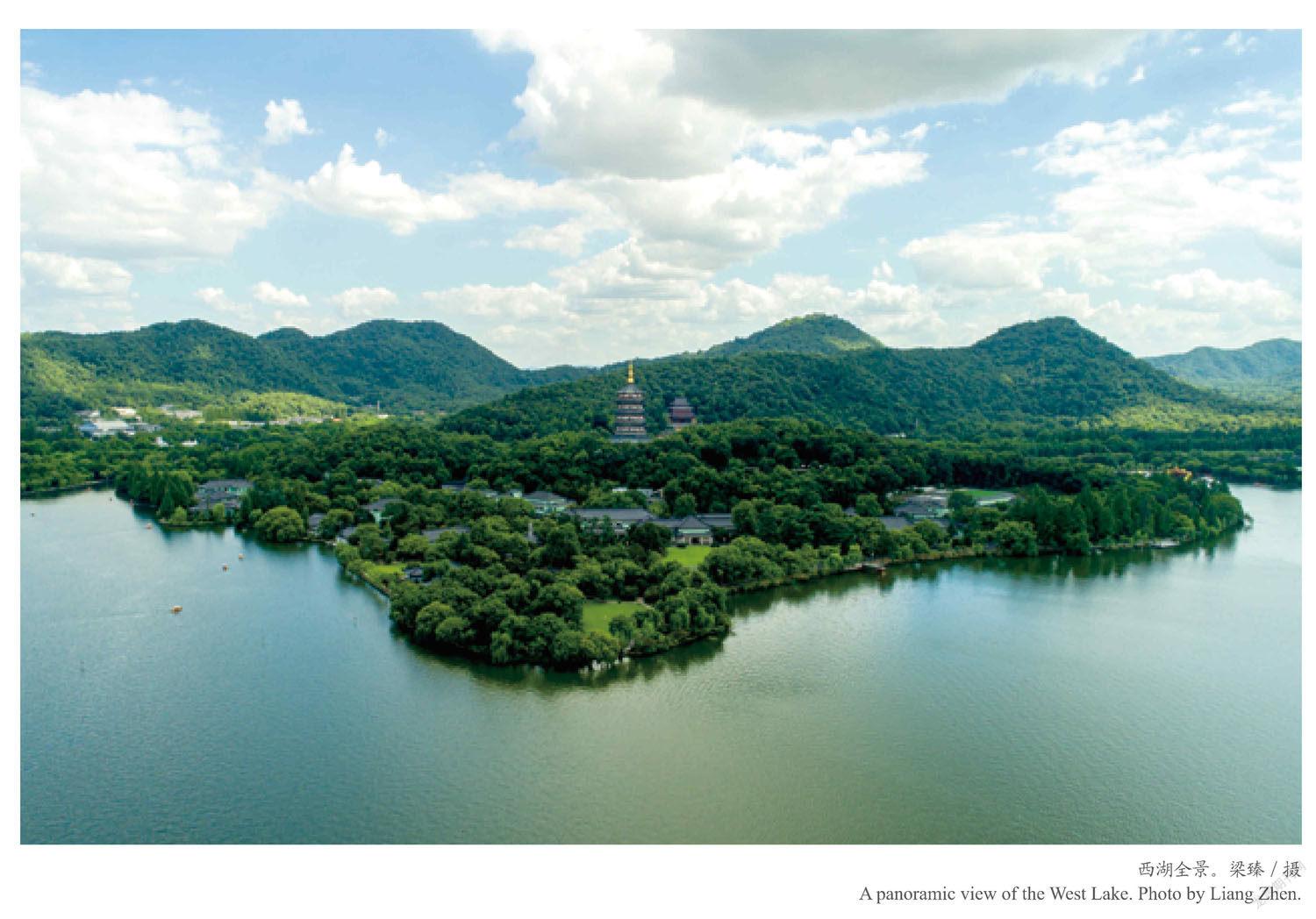

虎年的立春,杭城下了一场鹅毛大雪,白绒绒的雪花漫天飞舞,将西湖的山山水水裹上了银色的素装。

那一天,鬼使神差,我没来由地想起了自己人生第一份工作的所在——都锦生丝织厂,突然有一种想在春雪里寻故觅旧的冲动。细想想,冲动其实是有原因的。辞旧迎新,又长一岁,未免会产生老之将至的惆怅,在惆怅中怀旧,似乎是自然而然的事情。

1972年,我刚满18岁,高中毕业后被分配到都锦生丝织厂。记忆中,厂区里绿荫浓密,鲜花盛开。印象最深刻的是周恩来总理1957年视察工厂时说的一段话 :都锦生织锦是中国工艺品中的一朵奇葩,是国宝,要保留下去,要后继有人。如今这段话还陈列在都锦生故居内。

当时,我为自己能成为都锦生丝织厂的工人而自豪的。后来,我因为热爱文学而离开工厂,去了一家文学刊物做编辑,但却从来没有忘记过都锦生。

多年以后,我听说都锦生丝织厂的老厂房要拆迁,心里很是失落了一阵。工厂旧址地处杭州市区核心地段,那是多少商业大亨垂涎欲滴的黄金宝地。我曾去过那儿几次,厂房已不复存在,从前不绝于耳的织机声也早就喑哑,我还能到哪里去寻找当年那座美丽的花园工厂呢?

虎年开春,寻故觅旧的念头再一次冒出来,而且拂之不去,我在那一瞬间明白,都锦生依旧住在我的心里。老工厂虽然没了,老工厂的创始人都锦生的故居还在,我决定踏着春雪去寻访这位和我生命历程有过交集的先人旧踪。

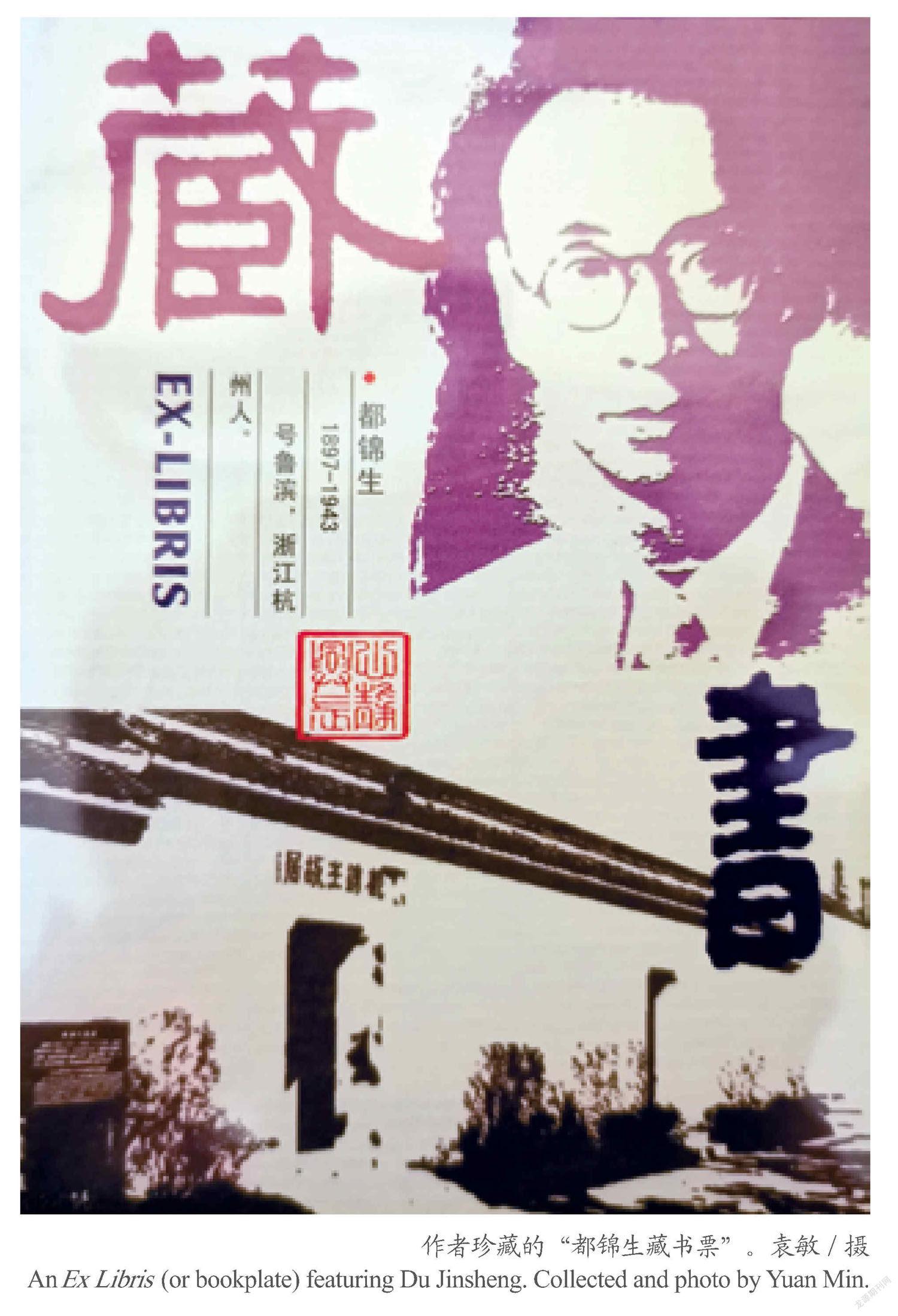

我找出了自己珍藏的一枚都锦生藏书票,那位戴着眼镜,眉眼和我非常崇敬的翻译家傅雷先生有几分神似的爱国实业家静静地看着我,仿佛在问:为什么找我?而书票中,都锦生肖像的下方,正是先生故居的黑白门墙,素朴肃穆,似乎在我耳边说:我在等你。

立春那天故居闭馆。我只好等到第二天再去。没想到,仅仅隔了一晚,鹅毛大雪裹卷的银白踪影全无。江南的春雪见水消融,留不住,能永恒的,只有西湖山山水水中淡泊的绿。

都锦生故居就藏匿在这片淡泊的绿中,它坐落在杭州绿意最浓的茅家埠。茅家埠位于西湖以西,东望杨公堤,西接龙井路。据《武林旧事》记载,从前居住在这一带的人家大多姓茅,他们以采茶养蚕为生。而“茅家埠”之名的由来,按当地村民的说法,不过是明清时村口船埠头茅草丛生,村里人随口叫叫沿袭至今罢了。由于这里旧时是前往灵隐和天竺寺上香拜佛的香客们弃舟登岸的码头,也是著名的“上香古道”起点,香客们常常在茅家埠吃了素斋,小憩片刻,然后沿着“上香古道”直奔天竺、灵隐,因此,历史上的茅家埠,曾经商铺云集,酒肆茶楼林立,热闹非凡。

而今天的茅家埠,反倒成为游人如织的西湖边难得的清幽之地,除了了解杭州的本地人会来此疏竹丛苇间漫步徜徉,或坐湖边石头上听风观水,一般游客很少到此打卡。

我坐公交车在龙井路的“五峰草堂”下车,穿过古色古香的“醉白楼”,沿着湖边的褐石小径往前走。这里长满了水杉、棕榈、野树杂草,虽然一眼望去,仍是残冬过后的满目凋零,但遍地新绿已经抵挡不住地冒出来,蓬蓬勃勃地舒筋展骨,将春意蔓延开来。在这样美妙的小径上行走,你会不由自主地放慢脚步,看看不远处湖面上青山的倒影,偶尔有一两只野鸭游过,剪开水波,荡起涟漪,却不会发出一丁点儿的声音。

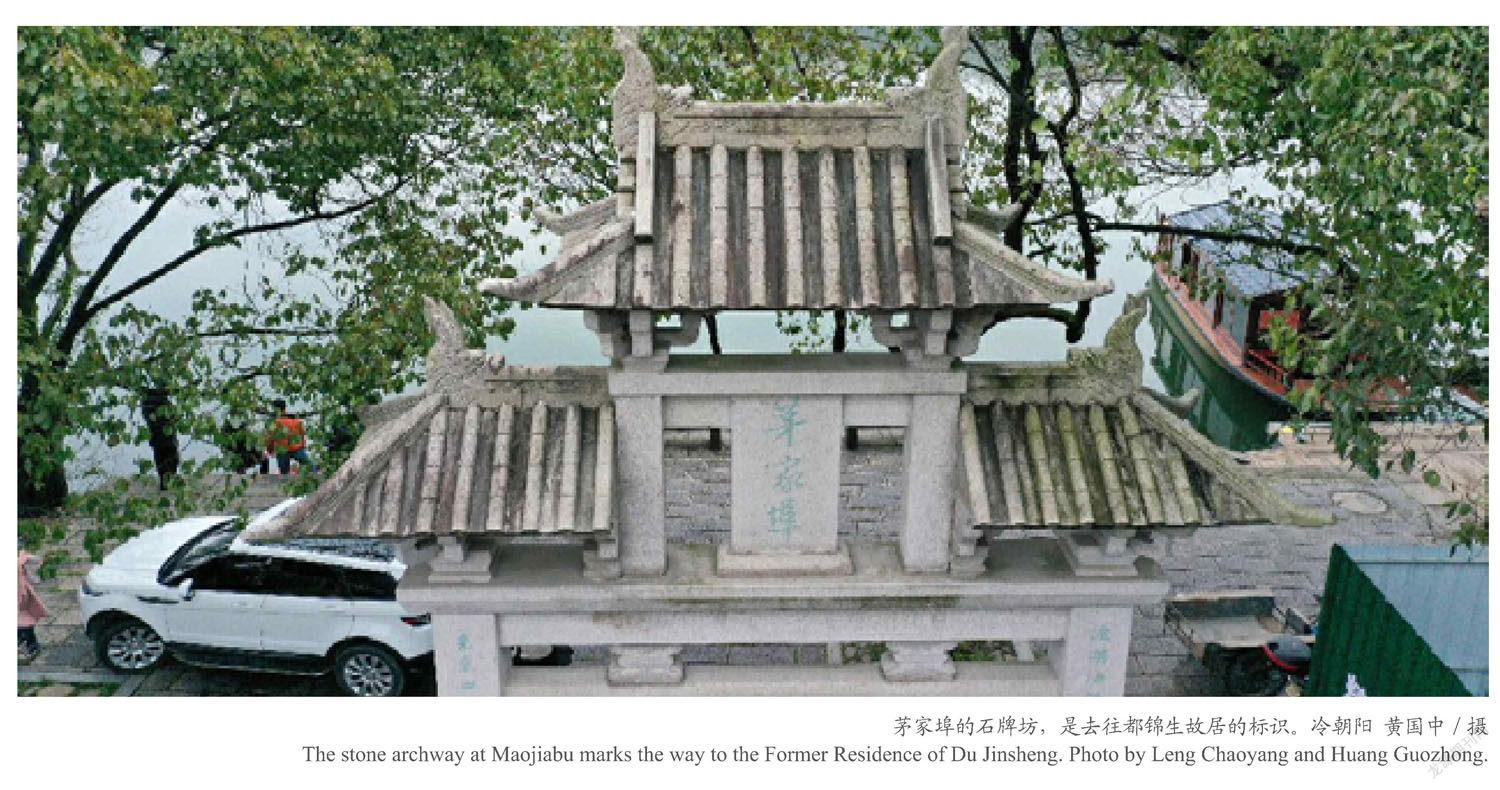

独步大约几百米后,我看到一条锈红色的画舫静卧湖中,旁边一大片木板地应该就是船埠头了。我想象着,当年的香客在湖滨下船,一路划到这里,从这里的船埠头登岸,一抬眼就能看到茅家埠的石牌坊,看到石牌坊前的老樟树。我不知道,多少年前,都锦生有没有站在这棵老樟树下向香客们展示自己的第一幅织锦,但他在距此一步之遥的故居里开办自己的织锦作坊,并在此第一次让都锦生织锦亮相,却是有文字记载的。

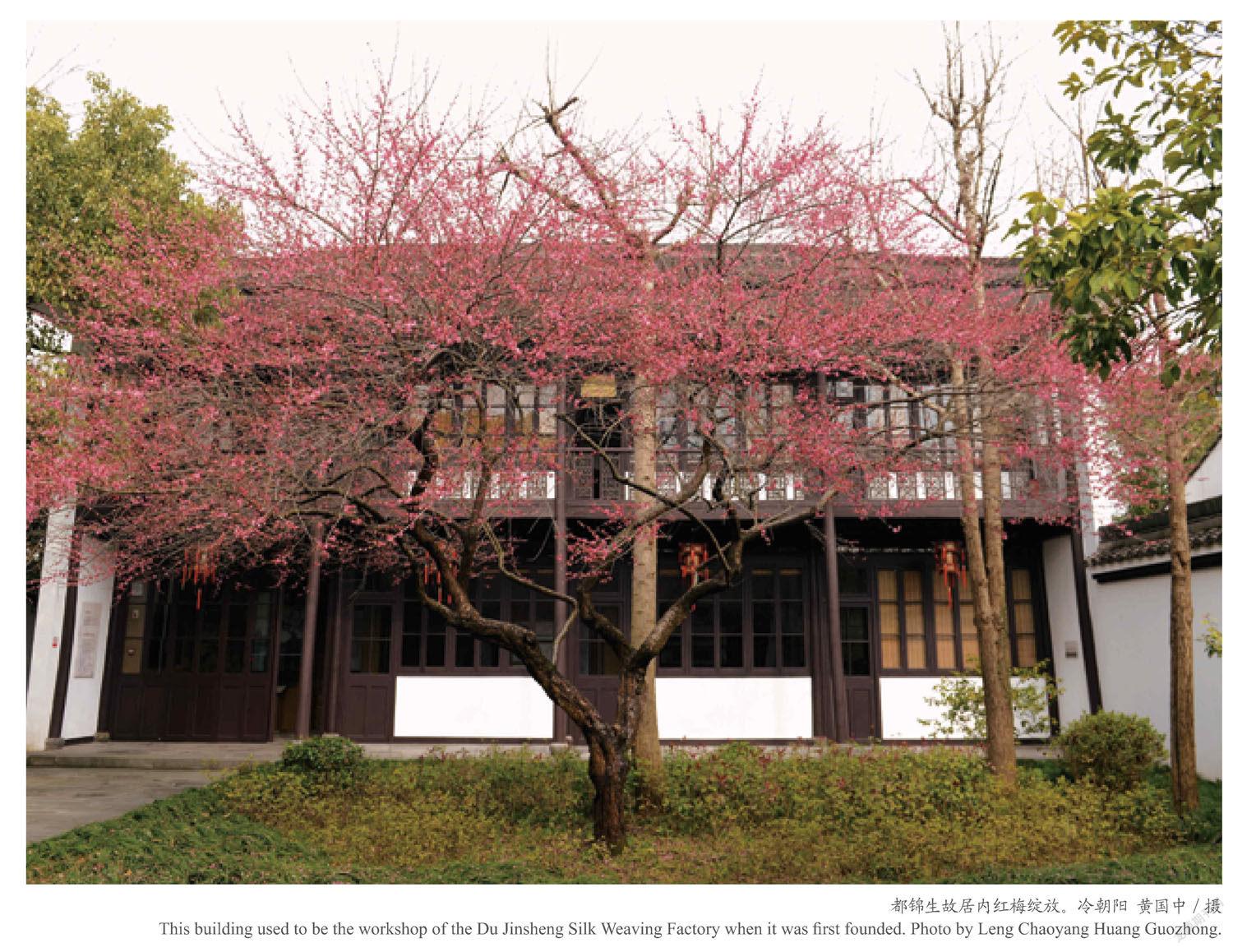

穿过石牌坊,再往前走几十米,黑瓦白墙的都锦生故居就出现在眼前。这一路,我几乎没碰到一个人,走进故居,在庭院里站了一會儿,也没见第二个来故居参观的人。

在清幽的庭院一角,都锦生雕像静静地伫立着,身后有几竿苍翠修竹,像他的身姿一样挺拔。都锦生眼睛里射出的具有穿透力的目光,仿佛在向你讲述久远的故事,让你觉得他似乎并没有走远。我想,来此参观的游人那么稀少,都锦生肯定是寂寞的,我不知道,这种寂寞有没有给他的内心带来荒凉,但我相信,他内心是不甘的。

春天是万物生灵苏醒的日子,也是树木花草欣欣向荣的时节,都锦生的一生和春天温暖缠绕,他在春天里降生,也在春天里成长;他在春天里绽放,也在春天里凋谢。这座普普通通的江南民居,陪伴都锦生经历了将近半个世纪的坎坷岁月,也见证了这位织锦大王执着追求的精彩人生。

1897年早春二月,都锦生降生在这里。父亲都宗祁既不种茶养蚕,也不开店经商,而是做了一名职业军人。他毕业于河北保定军官学校炮兵科,先后在清末新军和国民党军队中任下级军官。他养育了八个孩子,个个聪慧有才,而出类拔萃的都锦生,最得父亲的宠爱。

出生在如诗如画的茅家埠,都锦生自幼受到湖光山色的洇染和熏陶,热爱艺术,擅画风景,尤其喜爱摄影。19岁生日那天,父亲送他的生日礼物是一台照相机,都锦生背着这台照相机走遍了西湖的山山水水。那时候,他和父亲都没有意识到,这台照相机会在不知不觉中奠定了他的人生志向。

1919年,22岁的都锦生从浙江省甲种工业学校机织科毕业,留校任美术老师,兼做学校艺徒班的织制工场管理员。在教学实践中,都锦生很快就掌握了从设计到织造的丝织工艺全过程,与此同时,他拍下了很多幅西湖山水美景图。闲暇时,爱动脑筋的都锦生常常在心里琢磨,能不能将自己拍摄的西湖山水美景,用织锦技术制造出丝织工艺品呢?

在自己拍摄的众多西湖山水美景图中,都锦生尤爱那张“九溪十八涧”。其实,杭州的风景名胜中,九溪十八涧是相对偏远和冷僻的,它既没有平湖秋月的妩媚秀美,也不如柳浪闻莺的风姿绰约;既缺少断桥残雪的婉约缠绵,更难及雷峰夕照的雄伟壮观……但九溪十八涧是独特的,它拥有别处无法替代也不可能效仿的气质。清末著名学者俞曲园曾在《春在堂随笔》中盛赞“九溪十八涧乃西湖最胜处”,他写下的诗句:“重重叠叠山,曲曲环环路,叮叮咚咚泉,高高下下树”,将九溪十八涧的幽深美妙作了最好的诠释,给世人留下了深刻的印象。

也许是九溪十八涧骨骼清新非俗流的气质,契合了都锦生内心深处崇尚和追求的东西,又或许是九溪十八涧淡定旷达的从容,深得都锦生的喜爱,他研创的第一幅风景黑白织锦,即为“九溪十八涧”。

传统的丝绸锦缎,其纹样均由手工或写生或写意直接绘画而成,纹样结构变化比较简单,多为平纹、斜纹或五枚缎纹。都锦生觉得,这样陈旧的工艺,无法生动还原和表现出摄影图像的生动和逼真,必须进行改革创新。他经过刻苦钻研,反复试验,大胆摆脱老祖宗沿用了两千多年的丝绸锦缎常规设计画法,改成先以照相机拍摄好的风景照片为原本,再按照一定比例放大,然后做成纹版,并根据照片所呈现的溪涧风景自身特点,改用八枚缎的点子,以三十五种不同的色阶来表现明暗的光影层次,运用经丝纬线上跳动的半点、全点,构成了画面上的老树、小桥、溪涧流水,使织物图案凸显出与黑白照片几近一致的风景,细腻、生动、逼真、传神。可以说,都锦生研制的中国第一幅黑白风景织锦图《九溪十八涧》,做工精细,美妙绝伦,为中国近代丝绸技术史添上了一笔浓墨重彩。

1921年春天,都锦生时年23岁。“九溪十八涧”织锦图的试织成功,一炮打响,让年轻的都锦生信心大增,他进一步认清了自己的人生理想。当时,风雨如磐的旧中国正处于半封建半殖民地状态,国家的贫穷和落后,让中国人在世界上更是没有地位,相比在书斋里教书育人,都锦生觉得,实业救国也许是更值得做的事情!

不久,都锦生辞去了学校的教职,回到茅家埠,在自己家老宅的房子里筹建织锦作坊。

翌年,这幢坐落在茅家埠的普通江南民居,居然挂出了“都锦生丝织厂”的牌子。谁也不会想到,后来闻名全国、享誉世界的都锦生织锦,竟然由此启航。

一开始,都锦生只购置了一台织机,雇了一名工人,大部分的时间他都是自己上机梭织,雇来的工人只是给他打打下手。由于都锦生既是学机织科班出身,又有直接上机的反复实践,其工艺手段和制造技术炉火纯青,织出的风景图十分新颖别致、精美绝伦,更关键的是,价格非常亲民便宜,投放市场后很受大众欢迎。

小小的作坊不负“都锦生丝织厂”大大的名声,办得红红火火,产能迅速扩大。原来的茅家埠旧居已经容纳不了生产规模的扩大,都锦生又在杭州艮山门外置地建厂。几年后,都锦生丝织厂已拥有百余台织机、百余名工人,轧花机5台、意匠8人,产品也从单一的风景图像扩大到人像、名画、台毯、靠垫、床罩披肩、头巾、提花窗帘、室内装饰面料、旗袍和名族服装原材料等,生产经营档次不断提升。当然,在都锦生众多产品中,最经典的,仍然是各式各样的织锦图。

1926年,都锦生丝织厂生产的织锦远赴美国,参加费城的世界博览会,其中一幅彩色古画织锦《宫妃夜游图》引起轰动,一举荣获金奖,让中国人在国际上扬眉吐气。从此,“都锦生”名扬四海,为全世界瞩目。

然而,一家民族企业的兴衰,必定和国家的盛衰休戚相关。1931年“九一八事变”到1937年“七七事变”,这一年岁末,杭州沦陷。都锦生亲眼目睹国破家亡,悲愤欲绝,健康状况急剧下降。而侵略者却企图借助都锦生的名望和他曾东渡日本的经历,要其为伪政府效力。一身铮铮傲骨的都锦生坚决回绝,侵略者恼羞成怒,不仅一把火烧了艮山门外的都锦生大部分厂房和引进的新式织机,还洗劫了茅家埠老宅,就连远在广州、重庆等地的都锦生门市部,也难逃劫数,先后被战争的炮火炸毁。

都锦生不堪忍受骚扰破坏,工厂不断搬迁,每况愈下,最终还是难以维持。都锦生眼见自己的企业面临倒闭,心急如焚。但一介儒生无力反抗,无奈之下,他离开杭州,举家迁居上海。在上海期间,都锦生虽然也试图建造厂房,重新恢复生产,但终是内忧外患,积重难返,都锦生再也没有恢复元气。1941年12月,太平洋战争爆发,上海租界被占领,摇摇欲坠的都锦生丝织厂被迫倒闭,这给了都锦生致命一击。

1943年春末,都錦生忧郁成疾,病逝于上海,年仅45岁。

一代织锦魂驾鹤西去,但他发明创造的织锦技术却留给了后人,他曾经创造的辉煌与凝聚其毕生心血的灿烂织锦,也永远驻存在温柔美丽的西子湖畔。解放后,国家没有忘记这家老牌的民族企业,公私合营时,由政府投资在杭州市中心的凤起路重新建造了厂房,购置了机器,招聘了工人,都锦生丝织厂终于以国有企业的身份涅槃重生,亮相于世人面前。

待到我进都锦生丝织厂时,工厂规模已经与当年的老字号企业不可同日而语:一座座车间高大壮观,一台台新式织机操作简便,生产的花色品种层出不穷,高达上千种。当年周总理陪外宾到杭州参观,农必“梅家坞”,工必“都锦生”。曾经让创始人都锦生痛惜不已,濒临灭亡的都氏织锦工艺,不仅满血复活,重放异彩,而且不断改进,推陈出新!

我不知道,如今的都锦生丝织厂迁移去了哪里,但凤起路上依然保留着的都锦生织锦博物馆,记载了都锦生织锦及都锦生丝织厂跌宕起伏的前世今生,都锦生织锦门市部依然以其产品的独特魅力,吸引着来往的中外游客。都锦生织锦,还被原浙江省文化厅列为第一批国家非物质遗产名录上报国务院。2003年,在西湖综合保护工程中,都锦生故居作为杨公堤重要景观之一,更是得到了全面修复,并作为名人故居对游人开放。

我相信,历史不会忘记都锦生,这位为祖国丝绸织造工业作出巨大贡献的爱国实业家,亲手绘制的茅家埠的春天,是杭州一道亮丽的风景,而这道风景,无论到什么时候都不会消亡。

袁敏,女,作家、编辑、出版人。毕业于北京大学中文系,曾任《江南》杂志主编、浙江省作协副主席。1976年开始文学创作,现已创作发表小说、散文、报告文学等数百万字。尤其以长篇纪实文学《兴隆公社》《燃灯者》等引起读者和社会的广泛关注。

Du Jinsheng’s Splendid Brocade

By Yuan Min

The Year of the Tiger brought a heavy snow in Hangzhou, when an uncanny impulse came to me: I would like to pay a visit to my former work place — Du Jinsheng Silk Weaving Factory.

In 1972, at the age of 18, fresh from high school, I was assigned to work at Du Jinsheng Silk Weaving Factory, which I remember was full of trees and flowers. I was impressed by a placard bearing Premier Zhou Enlai’s instruction, made when he inspected it in 1957: “Du Jinsheng’s brocade is an exquisite gem of traditional Chinese handicrafts, and we should conserve it and train young people to inherit the techniques.”

I was so proud to be an employee there, although I left later to become a literary editor. Still, I miss it all the time.

Years later, I felt so lost as I heard that the factory was relocated. Originally situated in the busiest place of the city, it was so coveted by big businesses that even the time-honored brand was expected to be squeezed out in the tide of market economy. I was so sad for a while.

I returned there several times. The factory buildings were gone and most of the workers found other jobs. The deafening looms were no more. Where could I find the old garden-like factory?

While the factory is gone, I could still visit the former residence of its founder Du Jinsheng (1897-1943), hidden in a large piece of green at Maojiabu. One of the greenest places in Hangzhou, Maojiabu sits in the west of the West Lake, facing the Yanggong Causeway to its east and the Longjing Road to the west. According to Wulin Jiushi, or Ancient Matters from the Wulin Garden, most of the people, surnamed Mao (meaning “thatch”), used to live in this area by picking tea leaves and raising silkworms. But some local villagers believed it was so named just because several hundred years ago the area was overgrown with grass.

Since this place was the pier where Buddhist pilgrims landed, it was also the starting point of the famous “Ancient Road for Pilgrims”. Here pilgrims ate vegetarian meals and took a rest before going straight to the Tianzhu and Lingyin Temples. Therefore, Maojiabu was historically a prosperous place bustling with shops, restaurants and tea houses.

Today’s Maojiabu has become rather quiet, next to the tourists-filled West Lake. Except for local people, who will come here to stroll among the sparse bamboos and reeds, or sit on the rocks by the lake to listen to the wind and watch the water, tourists rarely drop by.

I got off my bus at the “Wufeng Thatched Cottage” on the Longjing Road, passed through the quaint “Drunken White House”, and walked along the brownstone path by the lake.

After walking alone for a few hundred meters, I saw a rust-red pleasure boat lying quietly in the lake and the wooden pier beside it. I imagined pilgrims embarking at the east lakeside and rowed all the way here. They landed from the pier here, looking up to the stone archway at Maojiabu, with an old camphor tree in front of it. I wondered if Du Jinsheng had stood under this old tree to show his first brocade to the pilgrims, though written record indicates that he started his own brocade workshop in his former residence nearby.

A few dozen meters beyond the stone archway, the Former Residence of Du Jinsheng, in black tiles and white walls, appeared. Along the way, I hardly encountered a single person, and standing in the courtyard for a while, I did not see a second visitor.

In a corner, Du’s statue stood quietly, with a few bamboo trees behind him, as green and tall as his figure. The penetrating gaze in his eyes seemed to be telling you a long story, as if he had not gone far. I thought that so few tourists coming here must have made him lonely. I didn’t know if this loneliness had brought desolation to his heart, but I believed that he wouldn’t accept this.

Du Jinsheng’s life was intertwined with the warmth of spring. He was born in spring and grew up in spring. He bloomed in spring and withered in spring. This ordinary of a Jiangnan (south of the Yangtze River) style dwelling accompanied him during half a century of ups and downs and witnessed the wonderful life that this king of brocade persistently pursued.

Du Jinsheng was born here in the early spring of 1897. His father, Du Zongqi, was a professional soldier who graduated from the Artillery Division of Baoding Military Academy, Hebei province, and served as a junior officer in the New Army during the late Qing dynasty (1616-1911) and the Kuomintang army. He begot eight children, all of whom were talented, and Jinsheng, who was outstanding, was most favored by his father.

Growing up in the picturesque Maojiabu, Du Jinsheng was influenced by lakes and mountains since childhood. He loved art, especially photography and he was good at painting landscapes. His father gave him a camera as his 19th birthday present. At that time, neither he nor his father realized that the camera would unknowingly change his life.

In 1919, the 22-year-old Du Jinsheng graduated from the Machine Weaving Department of Zhejiang Jiazhong Industrial School, serving as an art teacher and managed the weaving workshop for apprentice classes in the school. In teaching practice, Du quickly mastered the whole process of silk weaving from design to weaving; at the same time, he took many pictures of the beautiful West Lake. In his spare time, he often wondered whether he could use the brocade technique to create silk handicrafts from the beautiful scenery in his photos.

Among his pictures, Du Jinsheng loved the “Nine Brooks and Eighteen Dales” best. In fact, this scenic spot is relatively remote and secluded, not as charming, magnificent or graceful as other famous sites. But it is unique, with a temperament that cannot be imitated anywhere else. Yu Quyuan (1821-1907), a famous scholar in the late Qing dynasty, once praised “Nine Brooks and Eighteen Dales” as the most beautiful place in the West Lake”.

Perhaps it was the fresh and refined temperament of the “Nine Brooks and Eighteen Dales”, which was in line with what Du Jinsheng advocated and pursued in his heart, or perhaps it was the broad-minded calmness of the scene, which was deeply loved by Du, that the first landscape black-and-white brocade created by Du was the scenery of the “Nine Brooks and Eighteen Dales”.

The patterns of traditional silk brocade were all drawn by hand, sketch or freehand in style. The pattern structure varied not much, mostly executed in plain weave, twill weave or five-heddle satin weave. Du felt that such an outdated process could not restore and express the vividness and fidelity of photographic images, so it had to be renovated. After assiduous study and repeated experiments, he boldly got rid of the conventional silk design and drawing method that his ancestors had used for more than 2,000 years. Instead, he used the scenery in the photo as the original and enlarged it in proportion to make the plate. Then the features of the water scenes were converted into dots of eight-heddle satin, and thirty-five different color scales were used to express levels of light and shade, with jumping half-dots and full-dots on the warps and wefts to represent the old trees, small bridges and streams so that the fabric pattern highlighted the scenery that was almost the same as a monochrome photo, delicate, vivid, lifelike and expressive. It was the first black and white landscape brocade developed in China. The “Nine Brooks and Eighteen Dales” was exquisite and wonderful in workmanship, one of the representative silk works in China’s history of modern silk technology.

It was the spring of 1921, when Du was 23 years old. The successful trial weaving of the brocade “Nine Brooks and Eighteen Dales” was an instant hit, which greatly boosted the confidence of the young man, and he further recognized his ideals in life. At that time, the stormy old China was in a semi-feudal and semi-colonial status. The poverty and backwardness of the country rendered the Chinese people no place in the world. Compared with teaching, Du Jinsheng felt that saving the country through industry might be more important. Something worth doing!

Soon, Du resigned from his teaching position and returned to Maojiabu to build a brocade workshop. The following year, this ordinary Jiangnan dwelling actually bore the sign of “Dujinsheng Silk Weaving Factory”. No one would have thought that the Dujinsheng brocade, which was later famous all over the country and the world, would set sail from such a humble beginning.

At first, Du only possessed one loom and hired one worker. Most of the time he wove himself, and the worker just helped him. Because Du was a student in a weaving class with repeated practice directly on the machine, his craftsmanship and technology were very sophisticated, and the woven landscapes were novel, unique and exquisite. More importantly, the price was affordable. It was very popular on the market.

The small workshop earned the great reputation for “Dujinsheng Silk Weaving Factory”, and its production capacity expanded rapidly. The original residence could no longer accommodate the production, so Du Jinsheng set up a plant outside the Genshan Gate in Hangzhou. A few years later, Dujinsheng Silk Weaving Factory owned more than 100 looms, with more than 100 workers, five cotton gins, and eight designers. Their products expanded from simple landscape brocades to portraits, famous paintings, table rugs, cushions, bedspreads and shawls, headscarves, jacquard curtains, interior decoration fabrics, materials for cheongsam and ethnic clothing, etc. The production and operation level continuously improved. Among the many products, the classic ones were still various brocades with pictures.

In 1926, the brocade produced by Du Jinsheng traveled to the World Fair in Philadelphia. One exhibit, a colorful ancient brocade, The Night Tour of the Palace Consorts, caused a sensation and won a gold medal. “Du Jinsheng” has since become a famous brand all over the world.

However, the fate of a national enterprise was closely related to the prosperity of the country. In the Second World Word, the Japanese invaded China. Hangzhou fell to the invading forces in 1937, when Du Jinsheng‘s health failed him. However, the Japanese tried to use Du’s fame and his prior experience in Japan to recruit him in the puppet government. The proud Du resolutely refused, and the angry Japanese invaders not only set fire to most of Du Jinsheng’s workshops and the new-style looms outside the Genshan Gate, but also ransacked his old house at Maojiabu, even destroying his sales departments as far away as in Guangzhou, Chongqing by artillery fire.

Du Jinsheng couldn’t bear the harassment and destruction of the Japanese invaders, and constantly relocated his factory. He was devastated as he saw his company facing bankruptcy, but a businessman like him was unbale to put up much resistance. He left Hangzhou and moved his family to Shanghai, where his attempt to rebuild the factory was frustrated. In December 1941, the Japanese occupied the Shanghai International Settlement, and dealt the final and fatal blow to the crumbling Dujinsheng Silk Weaving Factory. In May 1943, Du Jinsheng died in Shanghai at the age of 45.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the government invested in rebuilding the factory on Fengqi Road in the center of Hangzhou. Dujinsheng Silk Weaving Factory finally reappeared as a state-owned enterprise.

When I joined Dujinsheng Silk Weaving Factory, the scale of the factory had already grown to be much bigger than that of the old enterprise. The workshops were grandiose, and the new looms were easy to operate. There were thousands of varieties of designs and colors. When Premier Zhou Enlai accompanied foreign guests to visit Hangzhou, they saw tea farmers at Meijiawu and workers at Dujinsheng. The Du brocade craft, which was on the verge of disappearing, was not only resurrected, but also revived with splendor!

I don’t know where the Dujinsheng Silk Weaving Factory moved to today, but the Dujinsheng Brocade Museum still stands on the Fengqi Road, which records the ups and downs of the Dujinsheng brocade and Dujinsheng Silk Weaving Factory. The Du’s Brocade stores still attract Chinese and foreign tourists with the unique charm of its products. The Dujinsheng brocade was also inscribed in the first batch of national intangible heritage list. In 2003, in the comprehensive protection project of the West Lake, the Former Residence of Du Jinsheng, as one of the important cultural landscapes of Yanggong Causeway, was fully restored and opened to tourists.

I believe that history will not forget Du Jinsheng, a patriotic industrialist who made great contributions to the silk weaving industry of China. The spring at Maojiabu painted with his own hand is a beautiful scene in Hangzhou, which will be forever alive.