Role of platelet-derived extracellular vesicles in traumatic brain injury-induced coagulopathy and inflammation

Liang Liu, Quan-Jun Deng

Abstract Extracellularvesicles are composed of fragments of exfoliated plasma membrane, organelles or nuclei and are released after cell activation, apoptosis or destruction. Platelet-derived extracellular vesicles are the most abundant type of extracellular vesicle in the blood of patients with traumatic brain injury. Accumulated laboratory and clinical evidence shows that platelet-derived extracellular vesicles play an important role in coagulopathy and inflammation after traumatic brain injury. This review discusses the recent progress of research on platelet-derived extracellular vesicles in coagulopathy and inflammation and the potential of platelet-derived extracellular vesicles as therapeutic targets for traumatic brain injury.

Key Words: angiogenesis; clotting factors; coagulopathy; delivery; inflammation; platelet-derived extracellular vesicles; review; target; traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) progresses through several phases. The initial injury, caused by mechanical forces, disrupts the functional and structural integrity of the brain. A series of subsequent reactions, including peroxide release, ischemia, coagulopathy and inflammation, leads to secondary injury in patients with TBI (Zhao et al., 2017). Secondary injury, especially coagulopathy, is the main cause of high mortality and disability rates in patients with TBI (Stein et al., 2002; Cap and Spinella, 2011; Zhao et al., 2020).However, the mechanisms of TBI-induced coagulopathy are complex and remain poorly understood.

Injury to the blood-brain barrier releases procoagulant materials that quickly and widely activate the exogenous coagulation pathway (Kurland et al., 2012; Joseph et al., 2014). Thus, TBI-induced coagulopathy manifests as a consumptive hypocoagulable state after rapid transition from a hypercoagulable state (Stein et al., 2002; Cap and Spinella, 2011; Yang et al.,2021), resulting in progressive bleeding and poor clinical outcomes.

Inflammation is another factor responsible for poor clinical outcomes in patients with TBI (Bonsack et al., 2020; Cheng et al., 2020). However, the mechanisms of TBI-induced inflammation remain poorly understood, as TBIinduced inflammation is also associated with central nervous system cells,such as astrocytes, neurons and glial cells.

Recently, the roles of extracellular vesicles (EVs), especially platelet-derived EVs (pEVs), in TBI-induced coagulopathy and inflammation have been of increasing interest. pEVs carry a variety of components, such as lipids,proteins (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor (Balvers et al.,2015)), nucleic acids (e.g., microRNAs (Nagalla et al., 2011)) and organelles(e.g., mitochondria (Boudreau et al., 2014)), which are involved in various biological processes, including hemostasis, inflammation (Puhm et al., 2021),angiogenesis (Hayon et al., 2012b) and intercellular delivery (Sprague et al., 2008). pEVs are a by-product of platelets (Wolf, 1967) and have similar,identical, and even more comprehensive functions than platelets. However,there is increasing support in the literature for the involvement of pEVs in pathological roles, such as in trauma, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis,sepsis, breast cancer and Huntington’s disease. pEVs are associated with disease severity in conditions such as trauma and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Milasan et al., 2016; Gomes et al., 2017; Denis et al.,2018; Fröhlich et al., 2018; Słomka et al., 2018; Dyer et al., 2019; French et al.,2020; Kerris et al., 2020; Kong et al., 2020; Tessandier et al., 2020). As patients with TBI often show platelet activation and release of pEVs, we suspect that an abnormally high number of pEVs may be responsible for poor outcomes in these patients. This review focuses on the systemic impact of pEVs released after TBI, with specific emphasis on TBI-associated coagulopathy and inflammation.

Search Strategy

The articles used in this narrative review were retrived by replicating the search terms of Boilard et al. (2010) and Zhao et al. (2017). We performed an electronic search of the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) for literature describing animal models of traumatic brain injury from 1967 to 2021 using the following medical subject headings (MeSH) search terms: TBI AND (models, animal) AND inflammation AND coagulants AND animal experimentation. In addition, we performed an electronic search of the PubMed database for methods of inducing plasticity by pEVs in humans.We included publications prior to May 2021, with the following search terms:traumatic brain injury (TBI), platelets, microvesicles, and inducing plasticity.

Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Coagulopathy

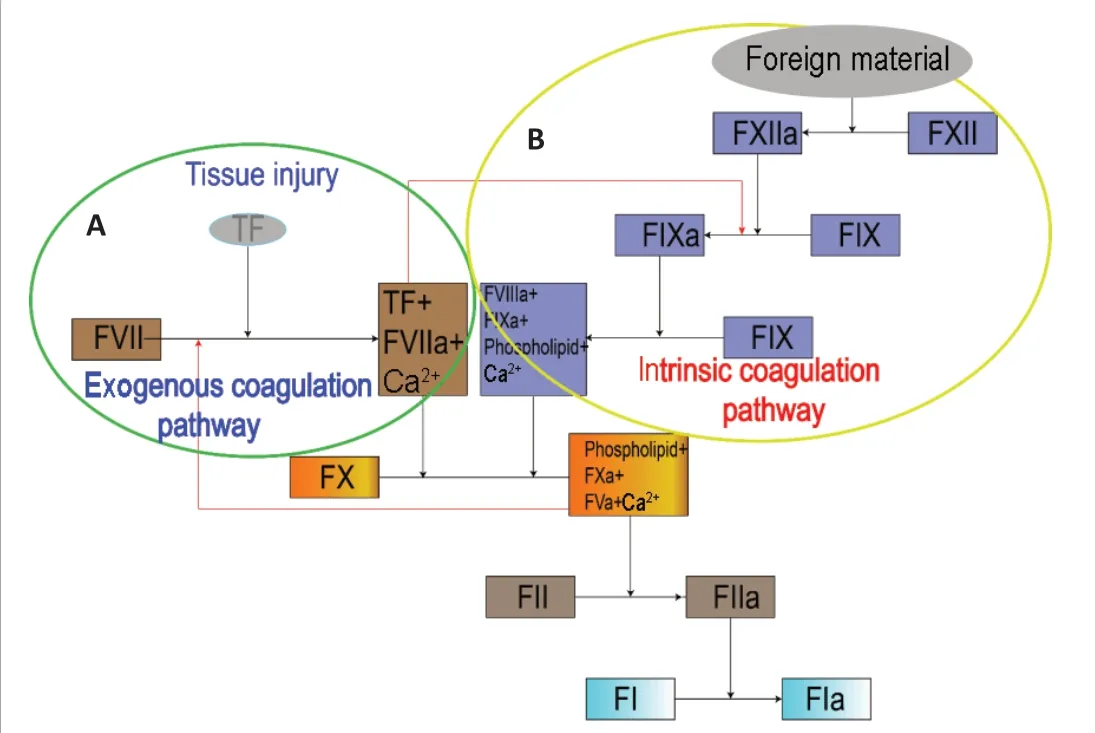

Tissue factor (TF), a membrane-transfer glycoprotein expressed by healthy fibroblasts, combines clotting factor VII (FVII) and Ca2+to form the activated FVII (FVIIa)-TF complex, which can act as a bridge between the exogenous coagulation pathway and the intrinsic coagulation pathway (Butenas et al.,2009; D’Alessandro et al., 2018; Grover and Mackman, 2018) (Figure 1).However, the amount of TF in circulating blood is not sufficient to cause clotting.

It has been shown that phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylethanolamine regulate the function of TF (Morrissey et al., 2010). Intriguingly, Rosas et al.(Rosas et al., 2020) demonstrated by mass spectrometry that pEVs express high levels of PS on their external leaflets, suggesting that pEVs exert an influence on coagulation through PS (Tripisciano et al., 2017). Additionally,the exposure of PS on pEVs promotes coagulation via another pathway that involves the transformation of TF from a quiescent form into a biologically active state (Chen and Hogg, 2013; Ansari et al., 2016; Bengtsson and Rönnblom, 2017; Grover and Mackman, 2018). Therefore, the procoagulant activity of pEVs is partly related to increasing activity of TF (Rosas et al., 2020).In addition, Tripisciano et al. (2017) found that pEVs are unable to facilitate the production of thrombin in the presence of corn trypsin inhibitor that specifically inhibits the activity of factor XII; however, in the absence of corn trypsin inhibitor, large amounts of thrombin are produced, suggesting that pEVs also promote clotting directly through the intrinsic coagulation pathway.Overall, pEVs significantly increase the amount of prothrombin complex through both intrinsic and exogenous coagulation pathways.

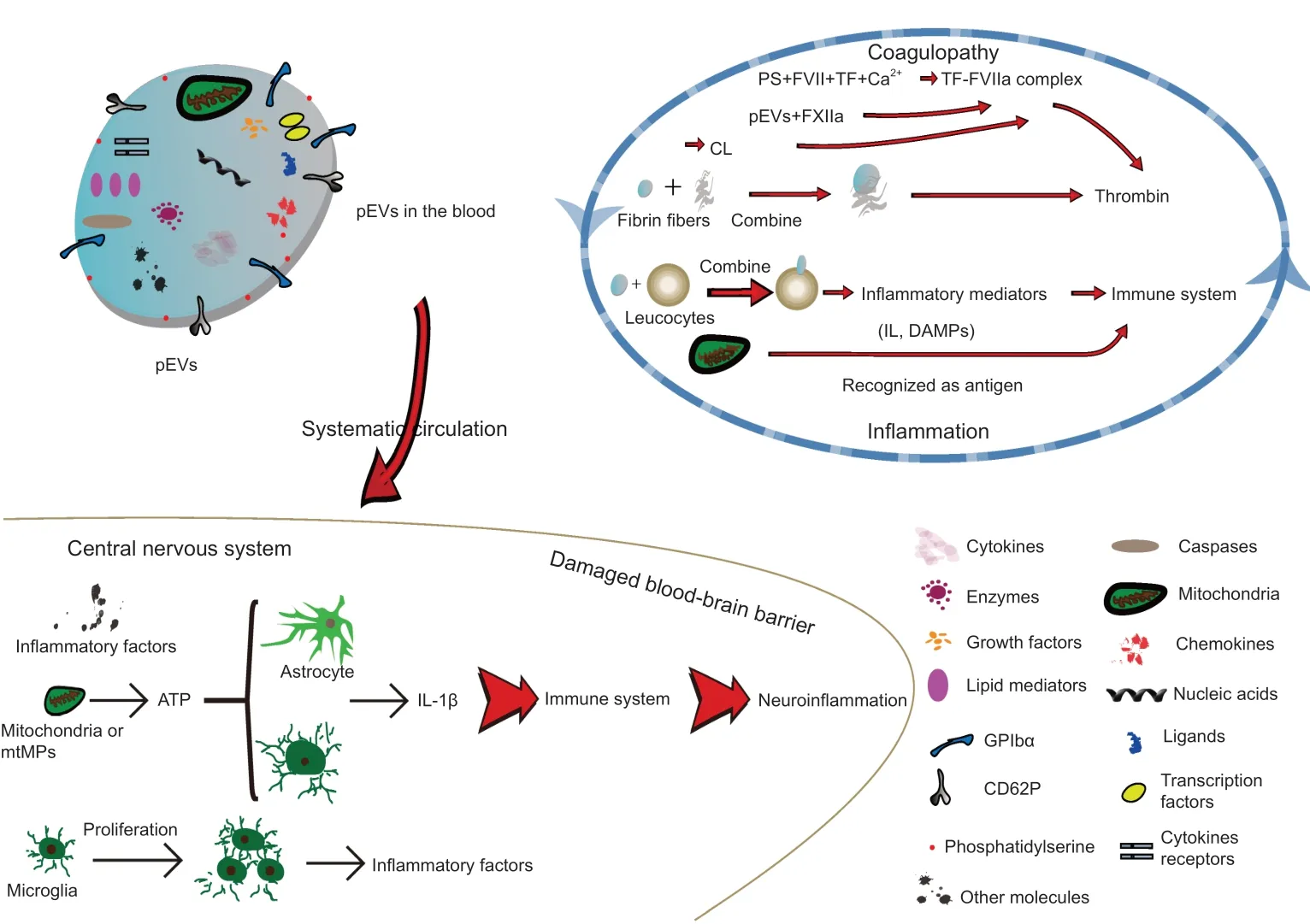

Boudreau et al. (2014) found that mitochondria can be incorporated into pEVs after platelet destruction. Interestingly, the inner membrane of mitochondria contains cardiolipin, which has a homologous structure to PS. Therefore,mitochondria promote coagulation by regulating the function of TF (Zhao et al., 2016). In addition to the effect of the contents of pEVs on coagulation,pEVs can directly bind to fibrin fibers to promote the generation of thrombin and formation of clotting through CD61+(Zubairova et al., 2015; Figure 2).

The role of pEVs in promoting coagulation has been demonstrated in many diseases. For example, patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura(ITP) have fewer platelets and therefore have a higher risk of bleeding than healthy people; however, some patients with ITP do not bleed more easilyowing to the presence of considerably higher numbers of pEVs than in patients with ITP and increased bleeding (Jy et al., 1992; Álvarez-Román et al., 2016). Therefore, pEVs may have a protective effect on patients with ITP by promoting coagulation. However, high levels of pEVs are associated with an increased risk of thrombotic conditions, such as in cancer, atherosclerosis,SLE and arthropathy (Levi et al., 2013; Boilard, 2017; Lacroix et al., 2019;Matsumura et al., 2019; Puhm et al., 2021). Conversely, PS exposure and dysfunction of EV release may result in severe hemorrhagic diseases, such as Scott syndrome (Zwaal et al., 2004). Stormorken syndrome, also called inverse Scott syndrome (Ridger et al., 2017), is a representative example of a condition presenting with mild bleeding even with high concentration of pEVs and is associated with either a gain-of-function mutation in the STIM1 gene (Misceo et al., 2014) or a loss-of-function mutation in the ORAI calcium release-activated calcium modulator 1 gene, a calcium channel pore-forming protein (Nesin et al., 2014).

Figure 1 |An overview of the coagulation process.(A) Exogenous coagulation pathway: Sufficient TF, released after tissue injury, combines with FVII and Ca2+ to form the FVIIa-TF complex. The complex can either activate FX to FXa, or it can activate FIX to form FIXa as a bridge between the exogenous and intrinsic coagulation pathways. (B) Intrinsic coagulation pathway: FXII can be activated by foreign material to form FXIIa. FXIIa activates FXI to form FXIa, and then FXIa activates FIX to form FIXa. FIXa combines with FVIIIa, phospholipid and Ca2+ to form a complex that activates FX to form FXa. FXa combines with FVa, phospholipid and Ca2+ to form the prothrombinase complex that activates FII (prothrombin), which subsequently activates FI to form FIa. FI: Clotting factor I/fibrinogen; FIa: activated clotting factor I/fibrin; FIX:clotting factor IX/plasma thromboplastin; FV: clotting factor V/proaccelerin; FVIIIa:activated clotting factor VIII/antihemophilic factor; FX: clotting factor X/stuart-prower factor; FXI: clotting factor XI/plasma thromboplastin precursor; FXIa: activated clotting factor XI; FXIIa: activated clotting factor VII/Hageman factor; TF: tissue factor.

As platelets are activated and pEVs are released after TBI, we speculate that pEVs are one of the important components present in the complex of procoagulant materials that are released after TBI. An early hypercoagulation response is followed by considerable depletion of coagulation-related factors, causing consumptive coagulation disorders and, eventually, delayed intracerebral hemorrhage.

Thus, pEVs are involved in both procoagulation and anticoagulation (Tans et al., 1991; Dahlbäck et al., 1992). However, the conditions and mechanisms behind the involvement of pEVs in procoagulation and anticoagulation remain to be studied further.

Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Proinflammatory Response

TBI is accompanied by inflammation. Damage to brain cells results in the release of brain-derived microparticles (BDMPs), including microparticles derived from astrocytes, neurons, glial cells and mitochondria (Zhao et al.,2016). In particular, adenosine triphosphate release from damaged brain cells stimulates the release of microvesicles from microglial cells (immune cells of the central nervous system) (Bianco et al., 2005), and subsequently,IL-1β, a proinflammatory cytokine and a component of the microglial microvesicles, is released after cleavage by its processing enzyme caspase 1 (Bianco et al., 2005). Similarly, astrocytes release microvesicles that contain IL-1β after stimulation by adenosine triphosphate (Figure 2) (Bianco et al., 2009). In addition, Hayakawa et al. (2016) showed that astrocytes release mitochondrial microparticles in a calcium-dependent manner that involves signals from CD38 and cyclic adenosine diphosphate ribose. This process increases the release of reactive oxide species and activation of caspases, inducing nerve cell apoptosis and subsequent release of neuronal microparticles containing IL-1β and miRNA-21, which ultimately leads to neuroinflammation and nerve injury after TBI (Cheng et al., 2012; Harrison et al., 2016). In contrast, we observed that mice treated with lactadherin,an apoptotic cell-scavenging factor that promotes the clearance of BDMPs(Zhou et al., 2018), had improved TBI prognosis compared with BDMPtreated mice. Lactadherin increased the expression of the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 and decreased the expression of the proinflammatory factor IL-1(Chen et al., 2019), providing further evidence that BDMPs are key players in inflammation.

Figure 2 |Role of pEVs to facilitate coagulopathy and inflammation after TBI.Brain damage promotes platelet activation and release of pEVs that contain a variety of components, including mitochondria, nucleic acids, cytokines and chemokines that facilitate coagulation via both intrinsic and exogenous coagulation pathways in the blood. pEVs can penetrate the blood-brain barrier to reach the central nervous system and promote neuroinflammation by inducing an immune response. These inflammatory and clotting responses reinforce each other, resulting in a vicious spiral. ATP: Adenosine triphosphate;BBB: blood-brain barrier; CL: cardiolipin; DAMP:damage-associated molecular pattern; FVII:clotting factor VII/proconvertin; FXIIa: activated clotting factor XII/Hageman factor; GPIbα:platelet surface glycoprotein receptor Ibα; IL:interleukin; mtMP: mitochondrial microparticle;pEV: platelet-derived extracellular vesicle; PS:phosphatidylserine; TBI: traumatic brain injury;TF: tissue factor.

Many publications report that pEVs promote inflammation via inflammatorymediated molecules and receptors (Semple and Freedman, 2010; Morrell et al., 2014; Kapur et al., 2015), including platelet surface glycoprotein receptor Ib α chain, cytokines, lipid mediators, chemokines (e.g., regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted), ligands, nucleic acids,transcription factors and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)(Lindemann et al., 2001; Ray et al., 2008; Boilard et al., 2010; Sahler et al., 2011; Laffont et al., 2013; Duchez et al., 2015; Boilard, 2018; Maugeri et al., 2018) (Figure 2). DAMPs are intracellular molecules released after tissue injury and cell death to initiate and propagate sterile inflammation(Seong and Matzinger, 2004; Rubartelli and Lotze, 2007). DAMPs include the heterodimeric protein S100A8/A9, the DNA binding protein high mobility group protein B1, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (Zhang et al., 2010;Boudreau et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Vogel et al., 2015). DAMPs facilitate activation of endothelial cells and innate immune cells, adhesion and transfer of white cells, monocyte maturation, and generation of cytokines and reactive oxide species (Boilard et al., 2010), causing an innate immune response and directly or indirectly initiating the adaptive immune response. Therefore,there is growing interest in DAMPs, and many studies have revealed that mitochondrial DAMPs, such as mtDNA, are closely associated with inflammation (Hajizadeh et al., 2003; Nakahira et al., 2013; Boudreau et al.,2014; Caielli et al., 2016; Garcia-Martinez et al., 2016; Lood et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2016; Marcoux and Boilard, 2017; Simmons et al., 2017). For example,in a series of studies of adverse reactions to platelet concentrate transfusion,including hemolysis, anaphylaxis and non-hemolytic febrile transfusion reactions, the levels of mtDNA, soluble CD40L, CD41 and soluble P-selectin in platelet concentrates were higher in patients with non-hemolytic febrile transfusion reactions than in those without adverse reactions (Boudreau et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014; Cognasse et al., 2016; Yasui et al., 2016; Simmons et al., 2017). In addition, reports have revealed that mitochondria, CD40L,CD41 and CD62P are components of pEVs (Dean et al., 2009), suggesting that pEVs are a likely source of mtDNA (Marcoux et al., 2019). Moreover,CD41 and CD45 have been used experimentally to label pEVs and leukocytes,respectively, and pEVs can combine with leukocytes to induce inflammation through platelet-type lipoxygenase 12 and group IIA phospholipase A2 carried by pEVs (Boilard et al., 2010; Duchez et al., 2015).

French et al. (2020) showed that pEVs can penetrate bone marrow (BM)in response to promacrophages to directly promote megakaryocyte regeneration in BM and to signal the occurrence of inflammation in BM.Changes also occur to pEVs in response to the plasma environment, so pEVs may transfer non-normal components to BM that interact with BM cells to influence their function. This process explains how BM cells can respond quickly to inflammation (French et al., 2020).

Several inflammatory diseases are associated with pEVs. In rheumatoid arthritis, platelets penetrate BM and are stimulated to release pEVs by platelet glycoprotein VI, a collagen receptor expressed on the surface of platelets (Boilard et al., 2010). Furthermore, IL-1 carried by pEVs induces fibroblast-like synoviocytes to release inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and the neutrophil chemoattractant IL-8 in a dose-dependent manner, which promotes inflammation by affecting innate and adaptive immune cells (Bester and Pretorius, 2016). Therefore, pEVs play a significant role in inflammation through IL-1-mediated activation of synovial cells. Bester and Pretorius have suggested that IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 facilitate inflammation.

The pathogenesis of SLE, an autoimmune disease characterized by the production of autoantibodies that typically target nucleic acids, is similar to that of TBI-induced inflammation. Apoptosis and the clearance of apoptotic cells and microvesicles are dysregulated in SLE (Mahajan et al., 2016;Bengtsson and Rönnblom, 2017). Accumulating evidence suggests that pEVs may serve as an antigenic pool owing to their components (Fortin et al.,2016). In particular, mitochondria and their components, such as mtDNA,have been confirmed as antigens in the pathogenesis of SLE. Mitochondria influence inflammation by activating receptors related to the innate immune system, such as Toll-like receptors, formyl peptide receptors and cytosolic pattern recognition receptors (Sandhir et al., 2017). In addition,the adaptive immune system participates in proinflammatory processes through antimitochondrial antibodies (Berg and Klein, 1986). mtDNA can be contained by immune complexes; these extracellular DNA-containing immune complexes are captured by Fcγ receptors, thereby activating the cyclic guanosine monophosphate/adenosine monophosphate synthasestimulator of interferon gene pathway and promoting the production of type I interferons, a hallmark of SLE (Pisetsky, 2012; Sun et al., 2013). The concentration of pEVs is associated with disease activity in SLE (Kanai et al.,1989; López et al., 2017; McCarthy et al., 2017), and different subtypes of pEVs are associated with distinct clinical manifestations (Bester and Pretorius,2016). Similarly, disease activity is attenuated during platelet depletion and inhibition of platelet function in lupus-prone mice (Linge et al., 2018), which further supports the role of pEVs in the occurrence and development of inflammation.

Interestingly, the number of pEVs is increased in infections caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, dengue virus and H1N1 influenza virus, and pEVs may serve as a biomarker of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (Cappellano et al., 2021).pEVs may exert an inhibitory effect on inflammation by reducing the production of tumor necrosis factor-α released by macrophages and IL-8 released by plasma dendritic cells (Ceroi et al., 2016). Thus, similar to coagulopathy, pEVs may exert bidirectional effects on inflammation depending on the conditions (Johnson et al., 2021).

Role of Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Angiogenesis in Traumatic Brain Injury

pEVs play a unique role in the treatment of intractable injuries, such as burns, tympanic membrane regeneration and chronic wounds caused by diabetes, by promoting angiogenesis and re-epithelialization (Guo et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2021; Schulz et al., 2021). Kim et al. (2004)identified that the lipids present in pEVs regulate proliferation, migration and tube formation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, and Brill et al. (2005) demonstrated that the proteins present in pEVs contribute to revascularization, including vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor. The benefits of angiogenesis and re-epithelialization promoted by pEVs have been demonstrated under a variety of conditions. For example, outcomes for an animal model of stroke can be improved by enhancing the differentiation potential of neural stem cells to form glial cells and nerve cells after addition of pEVs (Hayon et al., 2012a, b). Several studies have confirmed that pEVs positively modulate growth, migration and the differentiation potential of BM mesenchymal stem cells by upregulating the gene expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (Torreggiani et al., 2014; Rivera et al., 2015) to prolong the lifespan of mesenchymal stem cells (Johnson et al., 2021). Qu et al. (2020) recently reported in mice with acute liver injury that the density of megakaryocytes increased with an increase in circulating pEVs, but the amount of thrombopoietin was not upregulated.Co-culture of pEVs and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells promotes the differentiation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells into megakaryocytes and the subsequent generation of platelets by transferring miR-1915-3p to target cells to inhibit the expression of Rho-related GTP-binding protein RhoB, which is the only gene that downregulates the differentiation of megakaryocytes (Qu et al., 2020). A report suggest that proteins, lipids and nucleotides present in pEVs act as new effectors of tissue regeneration(Johnson et al., 2021).

In addition to contributing to adverse reactions of proinflammation and coagulation during the acute phase of TBI, pEVs also play a significant role in improving the outcomes of patients with TBI through vascular regeneration and nerve repair in the later phase. However, further investigations into the molecular mechanisms that connect pEVs with vascular regeneration are necessary.

Therapeutic Potential of Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

EV-based therapies have attracted a lot of attention, but attaining clinical application remains difficult (Lukomska et al., 2019). Most EV experiments to date have used mesenchymal stromal cell-derived EVs, and the use of platelets as a source of EVs has received relatively little attention (Johnson et al., 2021).

pEVs have several advantages compared with free platelets. pEVs improve hemodynamic stability (Lopez et al., 2019) and possess biological activity even after a freeze-thaw cycle of storage; the addition of pEVs to platelet suspensions overcomes the past challenges of storage and transportation of platelets, allowing platelets to be used within their half-life (Lopez et al.,2019). A variety of biological structures are expressed on the surface of EV membranes and allow the targeting of EVs to pathological sites to change the behavior of target cells (Agrahari et al., 2019b; Kao and Papoutsakis,2019; Mathieu et al., 2019). As pEVs play significant roles in coagulopathy,inflammation and angiogenesis, the findings above further signify the therapeutic potential of pEVs.

Accumulating evidence supports the potential of pEVs for delivery of therapeutics and activation of downstream pathways. According to a study by Kong et al. (2020) in the field of environmental science, pEVs can deliver particles smaller than 2.5 μm to human umbilical vein endothelial cells,leading to vascular endothelial injury. According to another study, pEVs can carry MCC950 to inflammation sites and inhibit the development of atherosclerosis, thereby solving the problem of coronary artery stenosis in the treatment of coronary heart disease (Ma et al., 2021). MCC950 is a nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, and pyrin domaincontaining-3 inflammasome inhibitor that blocks IL-1β release induced by nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, and pyrin domaincontaining-3 activator (Coll et al., 2019). Moreover, in the treatment of acute lung injury, pEVs selectively alleviate pneumonia progression by delivering[5-(p-fluorophenyl)-2-ureido]thiophene-3-carboxamide, which inhibits the production of inflammatory factors (Ma et al., 2020).

These findings collectively suggest that platelets absorb materials from the bloodstream, including proteins, liquids, nucleic acids and even harmful molecules, and activation of platelets stimulates the packaging of these molecules into EVs; the molecules then exert their effects after delivery by pEVs (Burnouf et al., 2014; Dovizio et al., 2018, 2020). Moreover, the biocompatibility and immune transparency of pEVs enable them to escape removal via biological interactions with the mononuclear phagocytic system or complement system. In addition, platelets are enucleated, which reduces the risk of mutation teratogenesis (Burnouf et al., 2014; Agrahari et al.,2019a). Therefore, pEVs have significant advantages for use in molecule delivery.

pEVs also have limitations. First, pEVs exert different qualitative and quantitative effects, depending on the method of their creation (Aatonen et al., 2014; Bei et al., 2016; Ponomareva et al., 2017; Ambrose et al., 2018).Aatonen et al. (2014) found that use of Ca2+ionophores lead to production of a larger number of pEVs than by using thrombin, collagen or adenosine diphosphate. However, proteomic analysis showed that Ca2+-generated vesicles are indiscriminately packaged and can carry significantly less protein cargo. Therefore, it is important to establish a more suitable and reproducible method to produce pEVs with optimal characteristics (Johnson et al., 2021).Second, there are currently no therapeutic application guidelines for the use of pEVs or mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles, and there are no standard procedures for the purification and characterization of pEVs. Finally,the concentration of pEVs cannot be accurately defined owing to the lack of a standardized test method, so it is more difficult to choose an appropriate blood concentration of pEVs to use as the treatment standard (Lopez et al.,2018). In conclusion, pEVs have great treatment potential, and this potential will be able to be realized further once standardized procedures have been defined by the research community (Lener et al., 2015; Table 1).

Table 1 |Advantages and disadvantages of using platelet-derived extracellular vesicles for therapy

Summary and Perspectives

pEVs contain a variety of components that allow them to have diverse functions, such as procoagulation and anticoagulation, proinflammation and anti-inflammation, angiogenesis and specificity in targeting and transport(Table 2). This review article focuses on the role of pEVs in promoting inflammation and coagulation, but owing to the diversity of components carried by pEVs, the many other effects of pEVs have not been described.TBI is accompanied by an increase in the number of pEVs, and pEVs may be a key player in TBI-induced secondary injury by the promotion of inflammatory and clotting responses. pEVs may also have a similar effect on microglial proliferation, which further promotes inflammation. Additionally,inflammation and coagulopathy reinforce each other, resulting in a vicious spiral. Although pEVs promote pathological conditions after injury, they show potential as a therapeutic target for the prevention and treatment of those pathological conditions. Thus, we eagerly await the development of a targeted method to reproducibly modify pEVs for clinical application to prevent TBI-induced secondary injury. Although pEVs have emerged as a new treatment for some diseases, such as intractable injuries and stroke,their role in TBI is still not well understood, and additional studies are needed to achieve the goal of therapeutic success in TBI.

Acknowledgments:The authors are grateful to Xin Chen, Zi-Long Zhao, and Ming-Ming Shi (Department of Neurosurgery, Tianjin Institute of Neurology,Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, Tianjin, China) for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

Author contributions:Manuscript design and writing: LL. Both authors

participated in editing this manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak,and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Functional in vivo assessment of stem cell-secreted prooligodendroglial factors

- iGluR expression in the hippocampal formation, entorhinal cortex,and superior temporal gyrus in Alzheimer’s disease

- Exploiting Caenorhabditis elegans to discover human gut microbiotamediated intervention strategies in protein conformational diseases

- N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor functions altered by neuronal PTP1B activation in Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia models

- Aminopeptidase A and dipeptidyl peptidase 4: a pathogenic duo in Alzheimer’s disease?

- Ubiquitin homeostasis disruption,a common cause of proteostasis collapse in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis?