A Contrastive Study of Self-Sourced Reporting Sentence Stems in English and Chinese Journal Articles

LI Zhuo-xuan,ZHANG Le

Self-representation has been widely established as a linguistic strategy to construct authority for better acceptance in academic writing. Self-sourced reporting sentence stems refer to the recurrent pre-constructed clausal semi-fixed sequences that perform the function of elaboration of the author’s argument. The present study adopts the Idiom Principle and conducts contrastive phraseological studies on the form and functions of self-sourced reporting sentence stems using comparable and parallel corpora. The study shows that (a) there exist in journal articles bountiful self-sourced reporting sentence stems; (b) sentence stems are the integration of meaning and form, and can be regarded as units of equivalence; and (c) self-sourced reporting acts are significantly different between English and Chinese academic cultures. The findings of this study could provide suggestions for teaching of academic writing, as well as translation practices.

Keywords: academic writing, translation equivalents, contrastive phraseology, sentence stem

Introduction

Recent studies suggest that during the writing of journal articles, professionals tend to seek effective interaction with their readers, under the premise of authenticity and intactness of data (Hyland, 2001). Writers tend to reveal information about themselves, such as their stances, opinions, and contribution to the field, especially through the use of first-person pronouns, which is a powerful tool for self-presentation (Ivanic, 1998). Self-mention has received increasing popularity in linguistic research (Hyland, 2015; Hyland, 2017; Maclntyre, 2019; Xie, 2020; Jiang & Hyland, 2020).

Numerous researches focus on classifying the authorial identity established by the author by using self-mentions (Tang & John, 1999; Gee, 2000; Bhatia, 2008). Hyland (2001, 2002, 2008) conducts extensive cross-disciplinary studies on self-mentions in academic writing, and revealing different writing conventions employed by academic writers from different fields. Charles (2006) provides a cross-disciplinary study of reporting clauses and divides them into self-sourced and other-sourced reports. Chinese researchers choose to focus on contrastive studies between English academic writing by Chinese and western scientists (Gao, 2015; Li & Xiao, 2018), and between English academic writing of Chinese EFL students and native scientists (Wang & Lou, 2018; Lou & Wang, 2020). However, there is still gap existing in multi-lingual and cross-cultural studies (Huang et al., 2008; Wu, 2013).

The concept of “self-sourced reporting sentence stems” in this research originates from “lexicalized sentence stem” proposed by Pawley & Syder (1983). With a structure of a subject and a predicate, a sentence stem refers to a clause that has fixed or semi-fixed structure and lexis. Idiom principle proposed by Sinclair(1991) offers new perspective for semi-fixed phrases: “there exists in language use a large number of semi-preconstructed units conveying author’s attitude and meaning on the levels of phrases and/or fragments”(Sinclair, 1991, p 110). Rooted in the Sinclairian view of language, sentence stem studies have received increasing popularity (Zhang & Wei, 2013; Li & Wei, 2017; Li & Pang, 2021), focusing on extraction and description of sentence stems in English academic discourses. However, multi-lingual and cross-cultural contrastive studies have received relatively less attention (Zhang & Li, 2012; Zhang & Lu, 2015).

Therefore, the present study looks at the clausal semi-fixed sequences used for self-sourced reporting purposes, that is, “self-sourced reporting sentence stems”, and explores their Chinese equivalents, hoping to acquire more information on similarities and differences between the construction of self-mention clauses in Chinese and English academic cultures. In this study we intend to provide insight to academic writing in both English and Chinese and translation of literature.

The present study employs research methods of contrastive phraseology, and focuses on consecutive lexical-grammar sequences that contain a subject-predicate structure with a self-mention as the subject in journal articles. This paper addresses three research questions: (1) What are the formal and functional characteristics of self-sourced reporting sentence stems in English and Chinese journal articles? (2) Is there equivalence between English and Chinese self-sourced reporting sentence stems? And (3) what are the similarities and differences of the way in which English and Chinese authors refer to themselves? And what are the reasons?

Corpora and Methods

The present study employs the humanities English and Chinese sub-corpora of the Corpora of Chinese-English Academic Papers (CCEAP), which consist of 400 English research articles and 400 Chinese articles from 20 humanities disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, sociology, and management from leading journals included in SCIEX, SSC and A&HCI databases. This study selects four disciplines, namely linguistics, sociology, life sciences and physics to represent a broad cross-section of academic practice. We select 20 journal articles from each discipline and only includes the abstract and the main body the paper, excluding other parts such as footnotes, reference, and acknowledgements. The sub-corpora include 533,171 English words and 716,704 Chinese characters. We used WordSmith 6.0 to search English corpora and LancsBox for Chinese. We also consulted Yi Yan parallel corpora (Xu X. & Xu J., 2021), and Collins COBUILD English-Chinese Dictionary, Oxford Advanced English-Chinese Dictionary, and Longman English-Chinese dictionary for reference. Research procedures are as follows.

First, we searched self-mention devices (I, me, we, us, my, our) in the English sub-corpora and extract self-sourced reporting sentence stems that occurred more than 5 times. The description of their formal and functional features was provided. We used three terms to indicate word sequences of different degree of abstraction: pattern, lexical sequence, and sentence stem. Pattern is the grammatical abstraction using parts of speech labels; lexical sequence is the actual representation directly extracted from the corpora, and sentence stem is an abstraction of lexis and semantics on the basis of pattern.

Second, recurrent Chinese translations were respectively searched for in parallel corpora and dictionaries.

Third, we used Chinese sub-corpora to examine the functional features of each Chinese counterparts drawn from step 2, and examine the authorial identities constructed by English and Chinese researchers to confirm equivalent relations.

Finally, we compared the formal, semantic, and functional features of English and Chinese self-sourced reporting sentence stems, and discussed the reasons of the similarities and differences.

Frequency of Authors’ Self-mention in Journal Articles

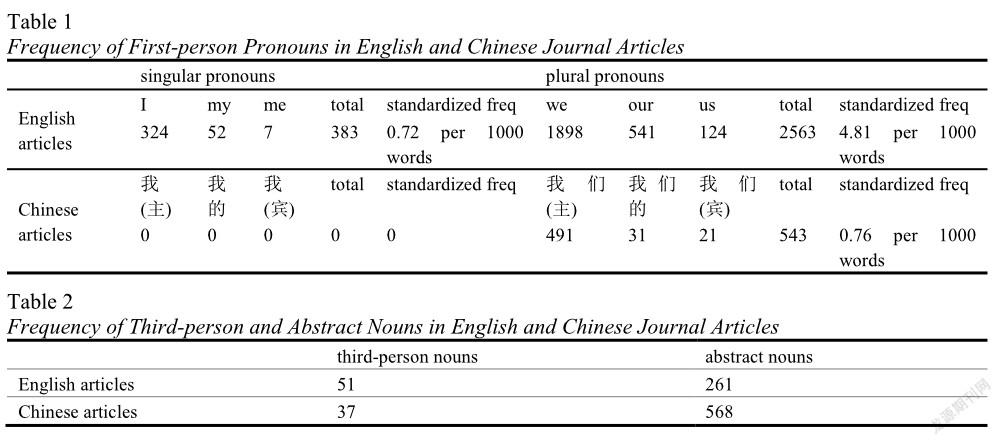

From Table 1, it can be seen that both English and Chinese RA authors are eager to highlight themselves, and English RA authors are more inclined to express themselves using first-person than Chinese RA authors. However, we believe that this alone does not offer enough evidence for us to say that English writers are more inclined to mention themselves, because there exist in Chinese journal articles numerous third-person nouns(e.g., the author) and abstract nouns (e.g., this article) utilized by Chinese writers for self-reference (Table 1). We can, however, conclude that English writers seem to be more engaged in their articles, due to the high accountability of first-person pronouns which indicates authors’ ownership of the information in the article(Huang et al., 2008). It is also clear that the singular first-person pronouns are widely used in English journal articles while Chinese authors avoid using 我 (wo, “I”). Therefore, we might say that in journal articles there is no direct Chinese equivalent of I. Lastly, Table 1 also demonstrates that first-person pronouns in English articles are usually used in the nominative form. Moreover, third-person nouns are much less frequently used. Therefore, this research will henceforward focus on the sentence stem containing plural first-person pronouns.

Metadiscoursal Functions of Self-sourced Reporting Sentence Stems

This section describes the form, semantics and functions of self-sourced reporting sentence stems and their Chinese equivalents. An academic paper is not simply the listing of facts or results. Researchers are required to employ appropriate writing strategies to elaborate their arguments in order to strengthen the credibility of their articles (Hyland, 2001).

This discoursal act does not only reveal the author’s evaluative stance, but also is the manifestation of the author’s values and affective attitude. Self-mention reporting sentence stems occurred 65 times in the English sub-corpora. Table 3 is a list of its typical lexical sequences.

It can be seen from Table 3 that self-sourced reporting sentence stems fall into 2 patterns:

[P1]: we (MODAL) V that

[P2]: we V (PREP)

In pattern [P1], when V is argue or suggest, MODAL is usually realized by would along with the less frequently-occurring might and will. The main verb V is usually an evaluative reporting verb such as argue, suggest, believe (Hyland, 1999). In more than 90% of the cases, the reporting verb is followed by a that-clause. The most typical lexical sequence is: we would argue that. The only verb that occurs in [P2] is think. Here, prepositions that occur in [P2] include of and about. [P1] and [P2] are both used to present author’s stance, and given the similarity in both the form and function of these two patterns, here we focus on [P1] for a more extensive discussion.

The typical sentence stem of [P1] is: we (MODAL) ARGUE that. Believe and suggest both occurred in[P1], and believe has a higher frequency. Hyland (1999) split reporting verbs into two categories, namely, denotation and evaluation. In the category of denotation, believe performs the cognition act. Evaluation category includes factive, non-factive, and counter-factive verbs. Argue is categorized as an author positive evaluative verb under non-factive category. Besides being a cognitive reporting verb, believe can also be used as an author tentative device categorized under non-factive reporting verbs along with suggest. Although Hyland did not categorize think as a reporting verb, Kaltenb?ck (2010) points out that think can serve as a hedging device, redressing the tone of the author.

Author’s certainty expressed through argue can be verified in the parallel corpora. Although argue that is mainly translated by “认为”, when the subject is a third-person noun (e.g., 本研究), there are cases where argue is translated by verbs with a strong positive attitude such as “坚称”, “主张”, for example:

(1) Original text: Greenberg argued that just as the destruction of the Temple brought forth the new institution of the synagogue…

Translation: 格林伯格坚称,就像圣庙的毁灭催生了新的犹太人集会机构那样……

In the parallel corpora, suggest that is also translated by “认为” when the subject is a human:

(2) Original text: Weighing alternate hypotheses, he suggests that such societies either are…

Translation: 关于这种替代性假说,泰勒认为这些社会或者是……

As for believe that, this phrase is mostly directly translated into “相信” in the parallel corpora. In a few cases it is translated by “认为”, or it is omitted by the translator:

(3) Original text: We believe that having the union involved as a full partner in the decision-making process at all levels of the corporation is essential to the success of the corporation.

Translation: 我们相信让工会作为全面的合作伙伴参与公司内各个层次的决策是公司获得成功的基础。

(4) Original text: Yet AI researchers have devoted little effort to passing the Turing Test, believing that it is more important to study the underlying principles of intelligence than to duplicate an exemplar.

Translation: 然而AI研究者们并未致力于通过图灵测试,他们认为研究智能的基本原理比复制样本更重要。

(5) Original text: I believe that we stand today at the precise point from which this great event can best be perceived and judged.

Translation: 今天我们所处的确切地位正好使我们能更好地观察和判断这个伟大事物。

First of all, “相信” only occurs 10 times in the Chinese sub-corpus, and it co-occurred with self-mention only once. Therefore, it is inappropriate to simply translate we believe that into “我们相信” in an academic discourse. Given that believe has been translated by “认为” in the comparable corpora, and neither believe nor“认为” conveys a clear evaluative stance of the author, achieving similar pragmatic functions, we can conclude that a direct equivalence between we believe that and “我們认为” can be established. Secondly, Chinese reporting verbs are used in a more flexible way in contrast to reporting verbs in English journal articles. Certainty is not only conveyed through the reporting verb itself. In another word, Chinese reporting verbs do not contain enough information to reveal the author’s assuredness regarding the particular statement. In example (6), the reporting verb co-occur with “理由” when the authors want to express certainty about the results or statement. However, in the English sub-corpora, argue has never co-occurred with any word that is related with “reason” or “evidence”. This finding suggests that when one translate such structures into Chinese, we may consider the strategy of amplification and add “(完全) 有理由” to highlight the translated version the sense of certainty, even though no such words appear in the original texts. Moreover, during the composition of English academic papers, we should avoid using “evidence” together with argue. Meanwhile, when the author is not absolutely sure of the claim, they may consider adopting hedging devices such as “可以” and changing the word order, such as (7):

(6) 因此,我們有理由认为秦岭地区有两个种,一个是循化鼠兔,—个是间颅鼠兔。

(7) 因此,可以认为我们选取的工具变量在理论上是合理的。

We can now conclude that the sentence stem “we ARGUE that” can be translated by “我们 (有理由/可以)认为” based on the characteristics of the reporting verb and the author’s assuredness. We found that clear equivalence could be established between we believe and “我们认为”, suggesting unclear attitude of the author. Secondly, there are positive words such as argue in English and “坚称” in Chinese, indicating similar level of certainty. However, Chinese authors would never use such verbs after self-mentions. Even though they are certifiably positive about their claims, Chinese authors tend to utilize phrases such as “有理由” to express certainty. This suggests the variety of English verbs, and Chinese writers do not have a great variety of verbs. Chinese writers tend to achieve similar metadiscoursal functions through the use of adverbs and the adjustment of word order.

Conclusion

The present research described the formal, semantic, and functional characteristics of highly recurrent semi-fixed clausal sequences drawn from the humanities sub-corpora of CCEAP covering natural sciences and humanities, and discussed the Chinese equivalent, and translation strategy.

It has been established that authorial engagement has significant interpersonal functions during manifestation and demonstration of authors’ argumentation and achievements. Improper use of or total banishment of self-mention devices may lead to obscurity. Studies of first-person pronouns in Chinese and English journal articles from the perspective of contrastive phraseology are important to domestic researchers’English academic writing. This study is of high pedagogical value to English academic writing; and could offer suggestions to translation practices.

Academic writing teachers must raise the awareness of the significance of self-representation in academic practices. Students must be taught to strategically harness self-mention devices to construct appropriate authorial identities in order to achieve effective and efficient communication with the academic community.

References

Bhatia, V. K. (2008). Worlds of written discourse: A genre-based view. New York, NY: Continuum.

Charles, M. (2006). Phraseological patterns in reporting clauses used in citation: A corpus-based study of theses in two disciplines. English for Specific Purposes, 25, 310-331.

Gee, J. P. (2000). Identity as an Analytic Lens for research in education. Review of Research in Education, 25, 99-125.

Hyland, K. (2001). Humble servants of the discipline? Self-mention in research articles. English for Specific Purposes, 20, 207-226.

Hyland, K. (2002). Authority and invisibility: Authorial identity in academic writing. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(8), 1091-1112. Hyland, K. (2015). Genre, discipline and identity. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 19, 32-43. Hyland, K. (2017). Metadiscourse: What is it and where is it going?. Journal of Pragmatics, 113, 16-29.

Ivanic, R. (1998). Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

MacIntyre, R. (2019). The use of personal pronouns in the writing of argumentative essays by EFL writers. RELC Journal, 50(1), 6-19.

Pawley, A., & Syder, H. (1983). Two puzzles for linguistic theory: Nativelike selection and nativelike fluency. In J. Richard & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and communication. New York: Longman.

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. London, Oxford University Press.

Tang, R., & John, S. (1999). The ‘I’ in identity: Exploring writer identity in student academic writing through the first-person pronoun. English for Specific Purposes, 18, S23-S39.

Xie, J. (2020). A review of research on authorial evaluation in English academic writing: A methodological perspective. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 47.

高霞. (2015). 基于中外科學家可比语料库的第一人称代词研究. 外语教学, (02), 30-34.

黄大网, 钟园成, 张月红. (2008). 自我指称与中国科学家的身份构建:学术论文引言章节的跨文化研究. 中国科技期刊研究, 19(5), 803-808.

姜峰 & Hyland, K. (2020). 互动元话语:学术语境变迁中的论辩与修辞. 外语教学, (02), 23-28.

李晶洁, 庞杨. (2021). 学术文本中的特征性句干研究:其型式与功能分布特征. 外语教学理论与实践, (01), 25-36.

李晶洁, 卫乃兴. (2017). 学术英语文本中的功能句干研究:提取方法与频数分布. 外语教学与研究, 49(02), 202-214+320.

李民 & 肖雁. (2018). 英语学术语篇互动性研究——以第一人称代词及其构建的作者身份为例. 西安外国语大学学报,(02), 18-23.

娄宝翠 & 王莉. (2020). 学习者学术英语写作中自我指称语与作者身份构建. 解放军外国语学院学报, (01), 93-99.

王莉 & 娄宝翠. (2018). 学习者学术英语写作中作者身份凸显度研究. 语料库语言学, (02), 58-68+115

吴格奇. (2013). 学术论文作者自称与身份建构——一项基于语料库的英汉对比研究. 解放军外国语学院学报, 36(3), 6-11.

张乐, 李晶洁. (2012). 学术语篇中的篇章性句干:型式、功能及双语对等. 山东外语教学, 33(06), 45-51+110.

张乐, 陆军. (2015). 科技文本中的it评价性词块:语料库驱动的短语对等原则与方法. 外语教学, 36(05), 35-39.

张乐, 卫乃兴. (2013). 学术论文中篇章性句干的型式和功能研究. 解放军外国语学院学报, 36(02), 8-15+127.

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2022年1期

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2022年1期

- Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- The Latest Development of Ethical Literary Criticism in the World

- Analyzing Darcy’s Pride and Change from a Naturalistic Point of View

- Barbara Longhi of Ravenna:A Devotional Self-Portrait

- Jewish Sources for Iconography of the Akedah/Sacrifice of Isaac in Art of Late Antiquity

- The Aesthetic Reception of Poetry Through Painting:“After Apple-Picking”as an Example

- The Media Fusion and Digital Communication of Traditional Murals—Taking the Exhibition of the Series of Tomb Murals in Shanxi During the Northern Dynasty as an Example