自恋与攻击性关系的元分析*

张丽华 朱 贺

自恋与攻击性关系的元分析

张丽华 朱 贺

(辽宁师范大学心理学院, 大连 116029)

本研究采用元分析技术探讨自恋与攻击性的关系。通过文献检索和筛选, 共纳入原始文献121篇, 含177个独立样本, 参与者总数达73687名。元分析的结果显示, 自恋与攻击性存在显著正相关, 二者关系受性别和自恋报告方式的调节, 但不受攻击性报告方式和文化的调节。同时, 不同类型的自恋与攻击性呈现出不同的相关程度, 内隐自恋与攻击性的相关程度高于外显自恋, 非适应性自恋与攻击性的相关程度高于适应性自恋。后续的研究应加强自恋测量的准确性, 注重探讨不同类型自恋与不同类型攻击性的关系。

自恋, 攻击性, 元分析

1 问题提出

攻击和暴力是全球普遍存在的公共卫生问题, 给个体、家庭和社会带来了巨大的伤害。传统观点认为低自尊是导致攻击性问题的重要原因, 但有研究者提出攻击性可能来自“受威胁的自我主义”, 即夸大、自恋的自我观受到威胁, 而不是低自尊本身(Barry et al., 2007; Baumeister et al., 1996)。诸多研究表明自恋与攻击性呈正相关(Rasmussen, 2016), 但这种关系的强度在各研究中差异较大(Kim et al., 2008; Kokkinos et al., 2016; Tanrikulu & Erdur-Baker, 2019)。另外, 还有研究结果显示自恋与攻击性不存在相关性(Ojanen et al., 2012)。Rasmussen (2016)对自恋与激发性攻击的关系进行了元分析, 但该研究没有将无端性攻击纳入元分析, 也没有探索文化对自恋与攻击性关系的影响。因此, 为了进一步理清自恋与攻击性的关系, 我们纳入基于中国样本的研究, 对自恋和攻击性的关系进行综合元分析, 以期加深对二者关系理解的一致性。

1.1 自恋与攻击性的关系

诸多研究发现自恋与攻击性呈正相关。最广泛用于解释自恋和攻击性关系的理论为受威胁的自我主义模型, 基于该模型, 自恋者往往需要通过他人的钦佩和肯定来确认自己不切实际的积极自我观和强烈的优越感, 当他们脆弱的积极自我观受到威胁时, 其内部评价和外部评价之间产生了差异, 这种差异会导致他们对自我威胁的根源产生负面情绪和敌意, 他们拒绝降低自我评价, 因而助长了攻击性(Baumeister et al., 1996)。

自恋暴怒理论认为, 与非自恋者相比, 自恋者对人际事件的反应更加强烈, 报告出更多的情绪变化和更高的情绪强度(Rhodewalt et al., 1998), 当自恋者受到威胁时, 会产生羞耻、愤怒、焦虑等负面情绪, 进而导致其攻击性增强(Krizan & Johar, 2015; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1998)。

自恋的心理动力学面具模型指出, 自恋者所表达的积极自我观不是完全真实的, 而是作为一种“面具”来掩饰自己潜在的低自尊(Zeigler-Hill & Besser, 2013)。基于这一模型, 攻击性可以被理解为潜在低自尊的公开表达(Barnett & Powell, 2016)。自恋的动态自我调节加工模型也认为, 自我调节加工是为了建立或维持期望的自我并满足自我评价需求而进行的有动机的自我建构。虽然自恋者的自我概念很浮夸, 但也非常脆弱, 这种脆弱性驱使自恋者不断激励自己通过各种个人机制和人际机制来维持他们膨胀的自尊。原则上可以通过多种方式来应对这种脆弱性, 比如通过回避行为将负面结果降至最低; 通过亲和与友好行为来获得社会认可和支持; 通过自我提升使积极结果最大化。自恋者似乎选择了自我提升的形式, 他们为了证实浮夸的自我观点, 达到预期的积极结果, 不管人际代价多大, 仍会采取攻击的方式提升自我, 旨在先发制人地降低失败的可能性或避免消极的后果(Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001)。综上所述, 自恋者的攻击性反应是调节情绪、认知、动机和行为的一种适应性机制(Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Washburn et al., 2004)。

还有一些研究发现自恋和攻击性不相关。有研究指出, 当自恋个体具有高自尊时, 在面对威胁信息后的反应不会那么具有攻击性, 而且可能会在察觉到自己轻微的反应后表现出更具建设性的行为(Hart, Richardson, & Tortoriello, 2018)。也有研究认为自恋与性格攻击性(dispositional aggression)无关, 而是对自我威胁有攻击性反应, 只要自恋者的优越感不被干扰, 他们会认为没有必要表现出攻击性(Jones & Neria, 2015)。

1.2 调节变量

第一, 自恋和攻击性存在性别差异, 因此有必要考虑性别在自恋和攻击性关系中的调节作用。就自恋而言, 研究发现男性的自恋水平往往高于女性(Grijalva et al., 2015)。就攻击性而言, 大多数的经验证据表明, 男性比女性更具有攻击性(Knight et al., 2002)。Wallace等人(2012)的研究发现, 相比于女性, 男性的自恋与攻击性的关系更强。综上, 提出本研究的假设H1:性别能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系。

第二, 报告的类型可能会影响自恋与攻击性的关系。以往自恋和攻击性的研究多采用自我报告的形式, 但自我报告容易受到社会期望的影响(Wallace et al., 2012), 尤其当问题涉及到社会无法接受的行为或特征时, 容易出现回答偏差。因此, 较于自我报告的攻击性, 自恋可能更与他人报告和行为测量的攻击性相关。另外, 自恋程度高的个体往往能够意识到自己的性格不能得到社会的高度评价(Carlson et al., 2011), 因此, 他们可能在必要时故意伪造自我报告(Heinze et al., 2020), 导致他人报告的自恋比自我报告的自恋与攻击性的相关程度更高。综上, 提出本研究的假设H2a:自恋的报告方式能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系; 假设H2b:攻击性的报告方式能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系。

第三, 文化也可能会影响自恋与攻击性的关系。面子是与集体主义文化相关的概念, 较于个人主义文化, 集体主义文化背景下的个体更为重视面子的保护, 更加在乎他人对自己的看法(Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005/2010; Bond, 2010)。因此, 在面对威胁时, 集体主义文化中的自恋个体更可能采用攻击行为以保护自己的形象。综上, 提出本研究的假设H3:文化能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系。

第四, 并不是所有类型的自恋都会表现出攻击性(Alexander et al., 2020)。Wink (1991)按照心理动力理论将自恋分为外显自恋与内隐自恋, 又分别称为浮夸型自恋和脆弱型自恋。外显自恋的特点是具有夸大的自我表现欲、公开地表达特权感、相信自己具有独特的能力和优越性并专注于从别人那里得到赞赏和关注, 而内隐自恋是一种更加隐蔽的自恋, 具有过于看重他人对自己的评价、缺乏自信、对批评和拒绝等威胁极度敏感的特点(Barry et al., 2015; Besser & Priel, 2010; Fan et al., 2016; Houlcroft et al., 2012)。这两种自恋都有傲慢和自我中心的核心特征, 但后者更易表现出防御性(Barry & Kauten, 2014), 具有更多的不适应特征(Fan et al., 2016)。综上, 提出本研究的假设H4a:自恋类型(外显自恋vs.内隐自恋)能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系。

此外, 根据适应功能可将自恋分为适应性自恋和非适应性自恋。自恋的适应性成分评估了个体的权威性、领导力和自我满足, 与自信、独立等品质有关, 与社会适应不良几乎没有联系(Amad, 2015; Raskin & Terry, 1988), 且高适应性自恋个体的自控力较好; 而自恋的非适应性成分评估了个体的特权感、剥削感和自我表现, 通常与敌意、难以延迟满足等有关, 且高非适应性自恋个体的理想自我与现实自我相差较大(Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995), 自控力较差(Ackerman et al., 2011)。因此, 较于适应性自恋, 非适应性自恋与攻击性可能具有更强的相关性。综上, 提出本研究的假设H4b:自恋类型(适应性自恋vs.非适应性自恋)能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系。

第五, 攻击性的多维度结构也可能会影响自恋与攻击性的相关强度。首先, 根据攻击的意图可将攻击分为主动性攻击和反应性攻击。受威胁的自我主义模型认为, 自恋只是在个体受到自我威胁后才与攻击性存在相关(Thomaes, Bushman et al., 2008), 描述了反应性攻击的过程, 隐含着反应性攻击和主动性攻击之间的区别。Baumeister等人(2000)指出, 只要没有受到自我威胁, 自恋者与非自恋者在攻击性方面没有很大差异。因此, 相对于主动性攻击, 自恋与反应性攻击的相关性可能更强。综上, 提出本研究的假设H5a:攻击性类型(主动性攻击vs.反应性攻击)能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系。

其次, 按照攻击形式可将攻击分为直接攻击和间接攻击。相比于直接攻击, 自恋者可能更倾向于使用间接攻击, 因为间接攻击的隐蔽性特点给自恋者一种错觉, 即尽管自恋者做出了伤害行为, 但呈现在他人面前的仍是其积极的一面, 有助于他们保持较高的社会地位(Bukowski et al., 2009; Golmaryami & Barry, 2010), 而直接攻击可能会破坏一个人的社交网络(Klimstra et al., 2014), 不利于自恋者维持或加强自己的统治地位。综上, 提出本研究的假设H5b:攻击性类型(直接攻击vs.间接攻击)能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系。

再次, Buss和Perry提出的攻击性问卷(Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire, BPAQ)将攻击性分为4个方面:言语攻击、身体攻击、敌意和愤怒, 其中身体攻击和言语攻击代表攻击性的直接形式, 愤怒和敌意分别代表攻击性的情绪和认知成分。内隐自恋个体对他人的评价非常敏感, 因而他们不会轻易公开表达自己的攻击性倾向, 但是由于他们具有一种特权感, 往往忽视他人(Wink, 1991), 在没有得到自认为应得的特别关注时, 容易产生愤怒和敌意(Okada, 2010)。综上, 提出本研究的假设H5c:攻击性类型(敌意vs.愤怒vs.言语攻击vs.身体攻击)能够调节内隐自恋和攻击性的关系。

最后, 攻击性可分为外显攻击和关系攻击。有研究指出女性比男性更重视社会交往中的关系问题, 因此女性更倾向于采用关系攻击以达到最大伤害效果, 而男性更重视社会支配性, 因而更倾向于采用外显攻击(Crick et al., 1997)。已有研究发现, 自恋与女性的关系攻击相关, 而与男性的关系攻击无关(Marsee et al., 2005)。综上, 提出本研究的假设H5d:性别和攻击性类型(外显攻击vs.关系攻击)的交互作用能够调节自恋与攻击性的关系。

2 研究方法

2.1 文献检索与筛选

在中国知网、维普、万方、Web of Science、Elsevier、Wiley和Pubmed数据库检索篇名、摘要或关键词中包含“自恋/narcissistic/narcissism”联合“攻击/aggressive/aggression”、“暴力/violent/violence”、“欺负/bullying/cyberbulling”的文献。检索时间范围为:1965~2021年, 最后一次的检索时间为2021年2月22日, 共检索到文献1200篇。

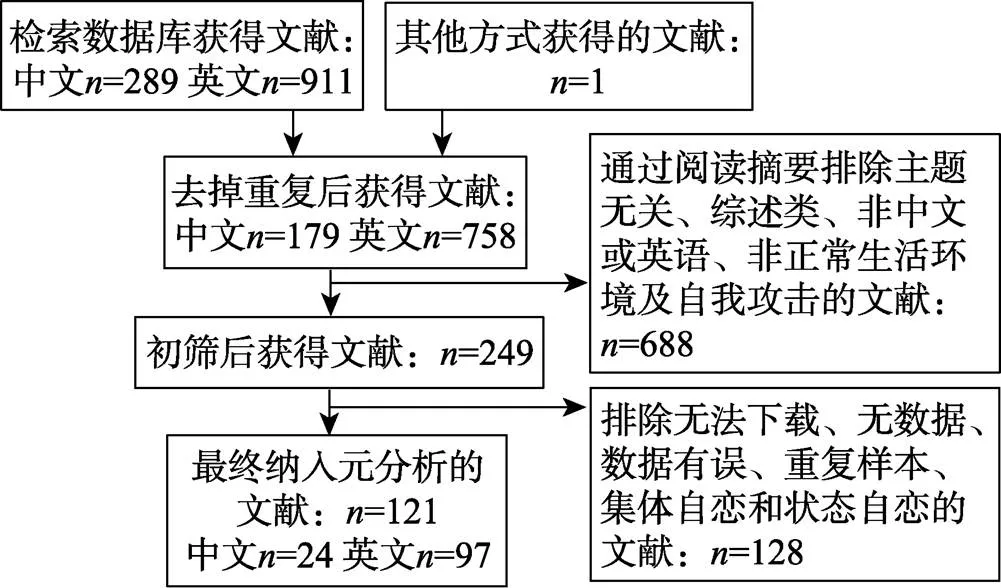

使用Endnote X9导入文献并按照以下标准筛选:(1)报告了自恋和攻击性总分或维度之间的零阶相关系数; (2)报告了样本量; (3)必须为实证研究, 综述性研究被排除; (4)对测量工具有明确的介绍; (5)重复数据仅选择信息更为充分的; (6)调查情境为正常的生活环境, 排除战争环境; (7)排除以自杀为攻击性结果的研究, 本元分析的攻击对象针对的是他人而不是自我; (8)状态自恋是指因为特定情境引起对自身重要性及自我形象暂时性夸大的状态(杨晨晨等, 2016)。集体自恋是一种认为自己所在的群体具有独特性, 但没有得到他人充分认可的信念(de Zavala, & Lantos, 2020)。限于国内外关于集体自恋和状态自恋与攻击性关系的文献较少, 而元分析研究需要有全面且系统的文献来支撑(丁凤琴, 赵虎英, 2018), 因此, 本元分析主要探讨了个体水平上的特质自恋对攻击性的影响, 排除了状态自恋和集体自恋。文献筛选流程见图1。最终共纳入177个独立研究, 样本量共计73687。

图1 元分析文献筛选流程图

2.2 文献编码

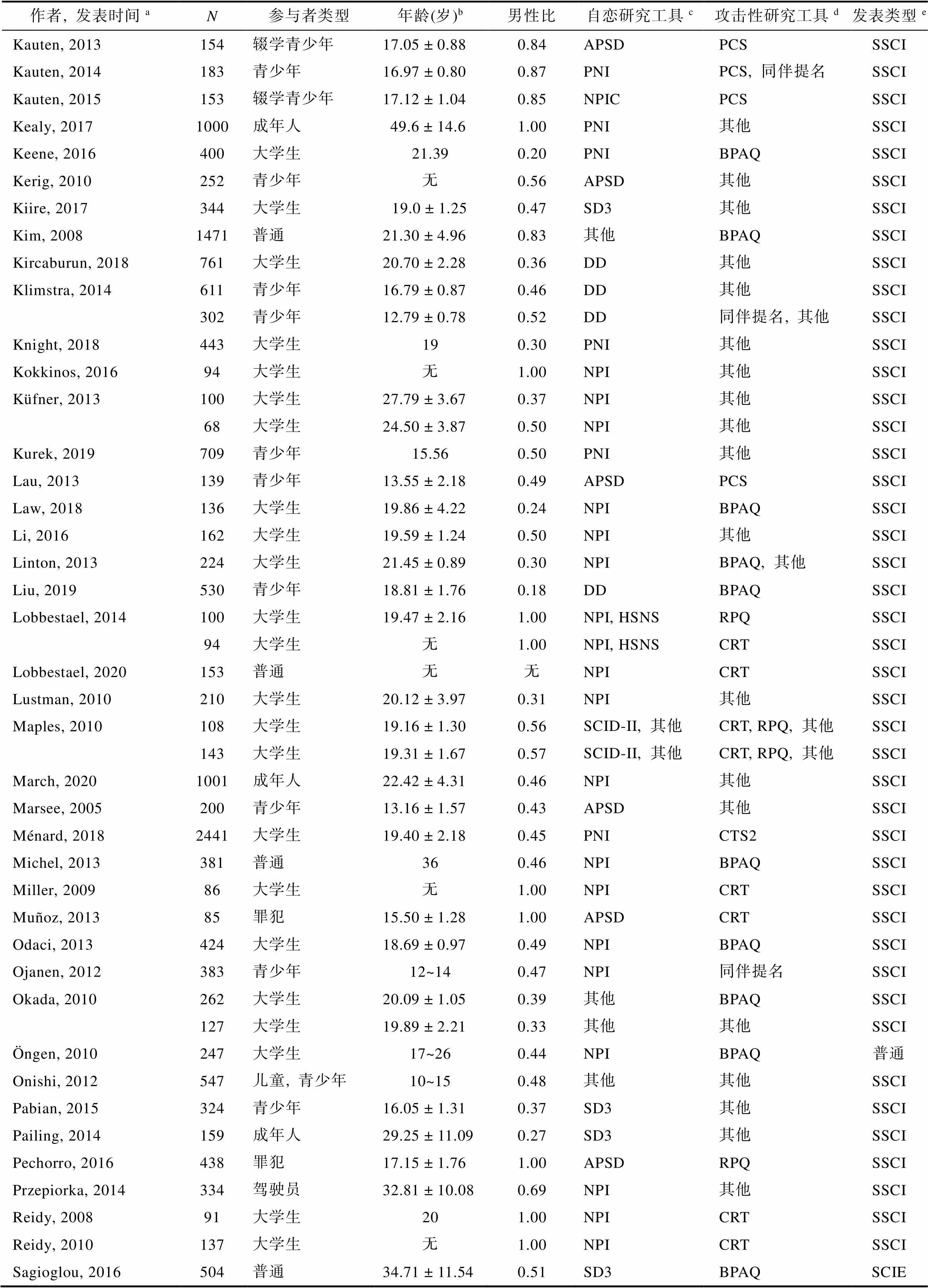

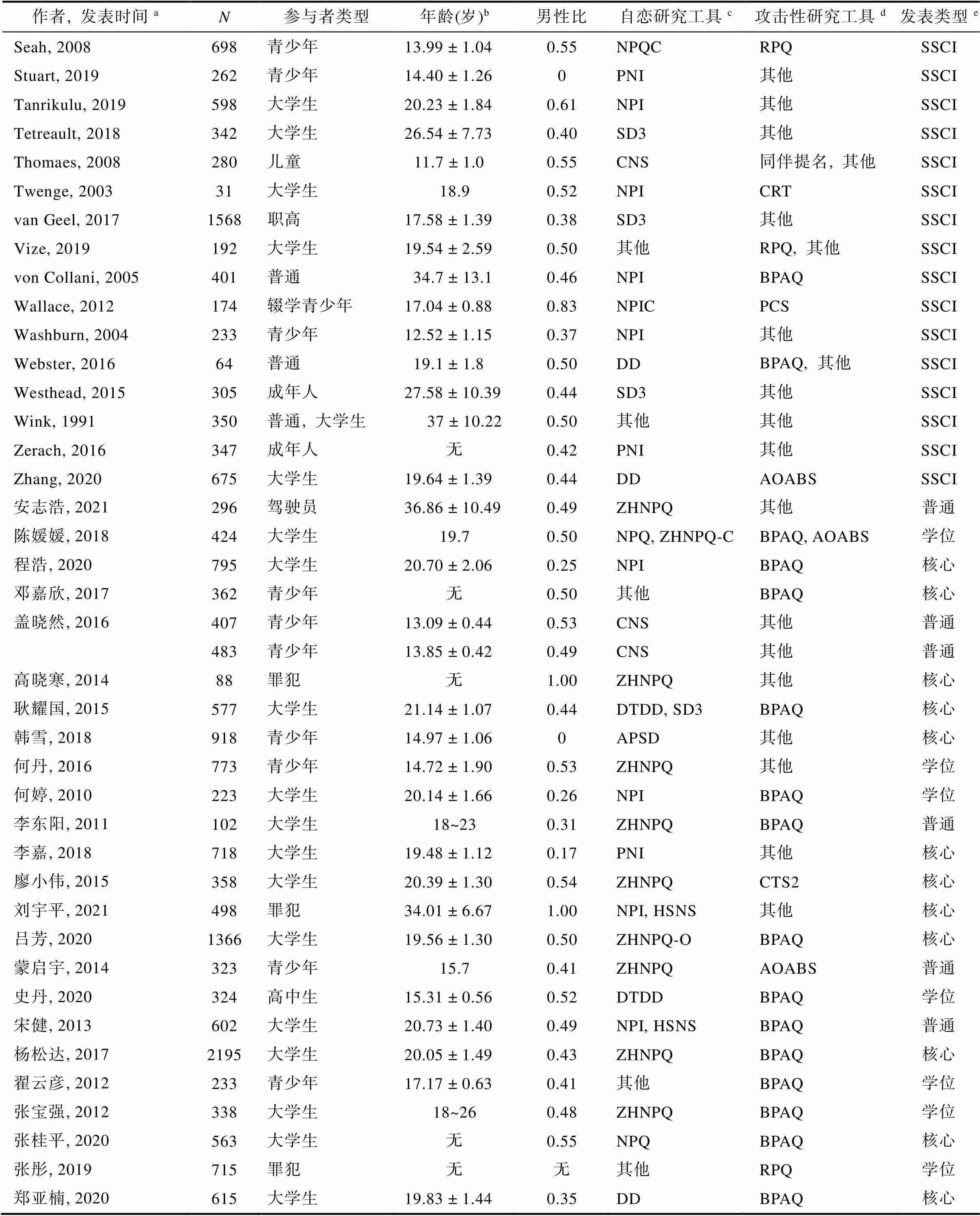

对作者信息、出版年份、发表类型、样本量、参与者特征(参与者类型、男性比、年龄)、文化背景、自恋和攻击性的测量工具、自恋和攻击性的报告方式(见表1)进行编码。自恋总分及各个维度与攻击性总分及各个维度的相关系数纳入编码, 独立样本编码一次, 若一篇论文报告了多个独立样本, 则分开编码; 若原始文献只报告了自恋和攻击性各个维度的相关系数或不同实验条件下(实验条件非本研究关注的调节变量)的相关系数, 则通过转换为后求均分, 然后再转为相关系数录入; 若实验条件为本研究关注的调节变量, 则分别进行编码。

表1 纳入的原始研究的基本资料

续表

续表

注:a 为减少篇幅, 仅列出了第一位作者。b 单个数字表示平均年龄。c ZHNPQ = 郑涌和黄藜的自恋人格问卷; ZHNPQ-O = ZHNPQ外显自恋分量表; ZHNPQ-C = ZHNPQ内隐自恋分量表; NPQ = 周晖等人的自恋人格问卷。d RPQ = Reactive and Proactive Aggression Questionnaire; AOABS = 少年网络攻击行为评定量表; CRT = competitive reaction-time task; CTS2 = Revised Conflict Tactic Scales; PCS = Peer Conflict Scale。e 核心 = 北大或南大核心期刊论文; 普通 = 一般公开刊物论文; 学位 = 硕博学位论文; SSCI = 社会科学引文索引; ESCI = 新兴资源引文索引; SCIE = 科学引文索引拓展版。

文化个人主义得分来自于Hofstede (2021)的数据库, 参考以往的研究(Cheng et al., 2021), 得分在50分或以上的国家被归为个人主义国家, 得分低于50分的国家被归为集体主义国家。

有些工具分别测量了内隐自恋和外显自恋两种形式的自恋, Pincus等人的病理性自恋问卷(Pathological Narcissism Inventory, PNI)及郑涌和黄藜的自恋人格问卷就是典型的代表。但很多量表没有说明所测量的自恋属于外显自恋或内隐自恋, 参考以往的研究(Gnambs & Appel, 2018; Grijalva et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2016; 陈媛媛, 2018), 自恋人格问卷(Narcissistic Personality Inventory, NPI)是外显自恋的典型例子, 因此, 54个条目、40个条目、16个条目、13个条目、37个条目版本的NPI, 以及NPI的儿童版Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children (NPQC)和Narcissistic Personality Inventory– Children (NPIC)、Jonason和Webster的黑暗十二条(Dirty Dozen, DD)的自恋分量表也被归类为外显自恋的衡量标准。此外, 我们还将如下的测量工具归为外显自恋:Jones和Paulhus的短式黑暗三联征量表(Short Dark Triad, SD3)的自恋分量表; 米隆临床多轴问卷第三版(Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-Ⅲ, MCMI-Ⅲ)的自恋型人格障碍分量表; First等人的人格障碍诊断问卷(Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-Ⅳ Axis Ⅱ, SCID-Ⅱ)的自恋分量表; Thomaes等人的童年期自恋量表(Childhood Narcissism Scale, CNS); 反社会过程筛查表(Antisocial Process Screening Device, APSD)自评版和他评版; 周晖等人的自恋人格问卷。而Hendin和Cheek的过度敏感自恋量表(Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale, HSNS)则是衡量内隐自恋的典型例子。

2.3 数据处理与分析

采用CMA 3.3 (Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 3.3)软件对数据进行元分析的主效应分析和调节效应分析, 调节效应分析采用元回归分析。

3 研究结果

3.1 同质性检验及模型选定

通过对纳入的效应量进行同质性检验发现,= 1793.44 (< 0.001), 表明结果存在异质性;= 90.19, 表明模型中有约90.19%的观察变异来自效应值的真实差异, 约9.80%的变异来自随机误差,大于75%, 表明结果存在高异质性。因此, 自恋与攻击性的元分析采用随机效应模型, 有必要分析调节变量对自恋和攻击性关系的影响。

3.2 发表偏差

漏斗图显示, 自恋与攻击性关系各效应值大部分集中在顶部且均匀分布在总效应的两侧; Egger直线回归法显示,为−0.24,= 0.678。这些结果表明研究结果受出版偏误的影响较小, 自恋与攻击性关系的元分析结果较为稳定。

3.3 主效应检验

采用随机模型综合分析自恋与攻击性的整体关联程度, 结果显示, 自恋和攻击性的相关系数为0.27, 95% CI [0.25, 0.29]。根据Gignac和Szodorai (2016)的标准, 可以认为本研究中自恋和攻击性存在中等程度的正相关。

3.4 调节效应检验

性别可以显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系。元回归分析(173个效应值)的结果发现, 男性比对效应值的回归系数显著(= 0.10),= 0.026。男性比越高, 自恋和攻击性的相关系数越高。

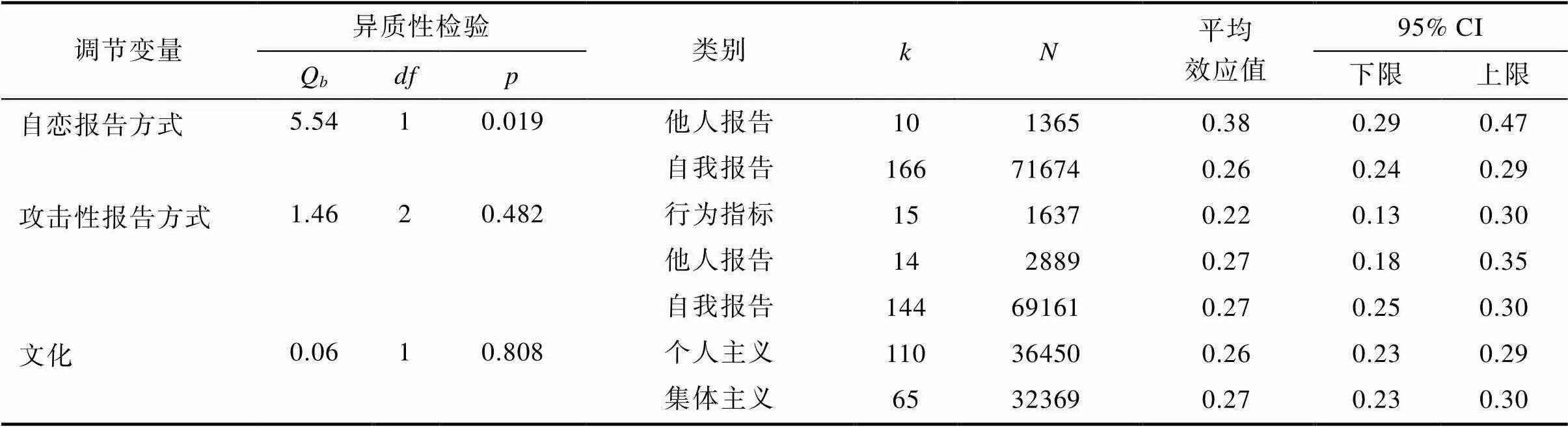

如表2所示:(1)自恋报告方式可以显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系(Q= 5.54,= 0.019), 他人报告的相关系数显著高于自我报告的相关系数。(2)攻击性报告方式不能显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系(Q= 1.46,= 0.482)。(3)文化不能显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系(Q= 0.06,= 0.808)。

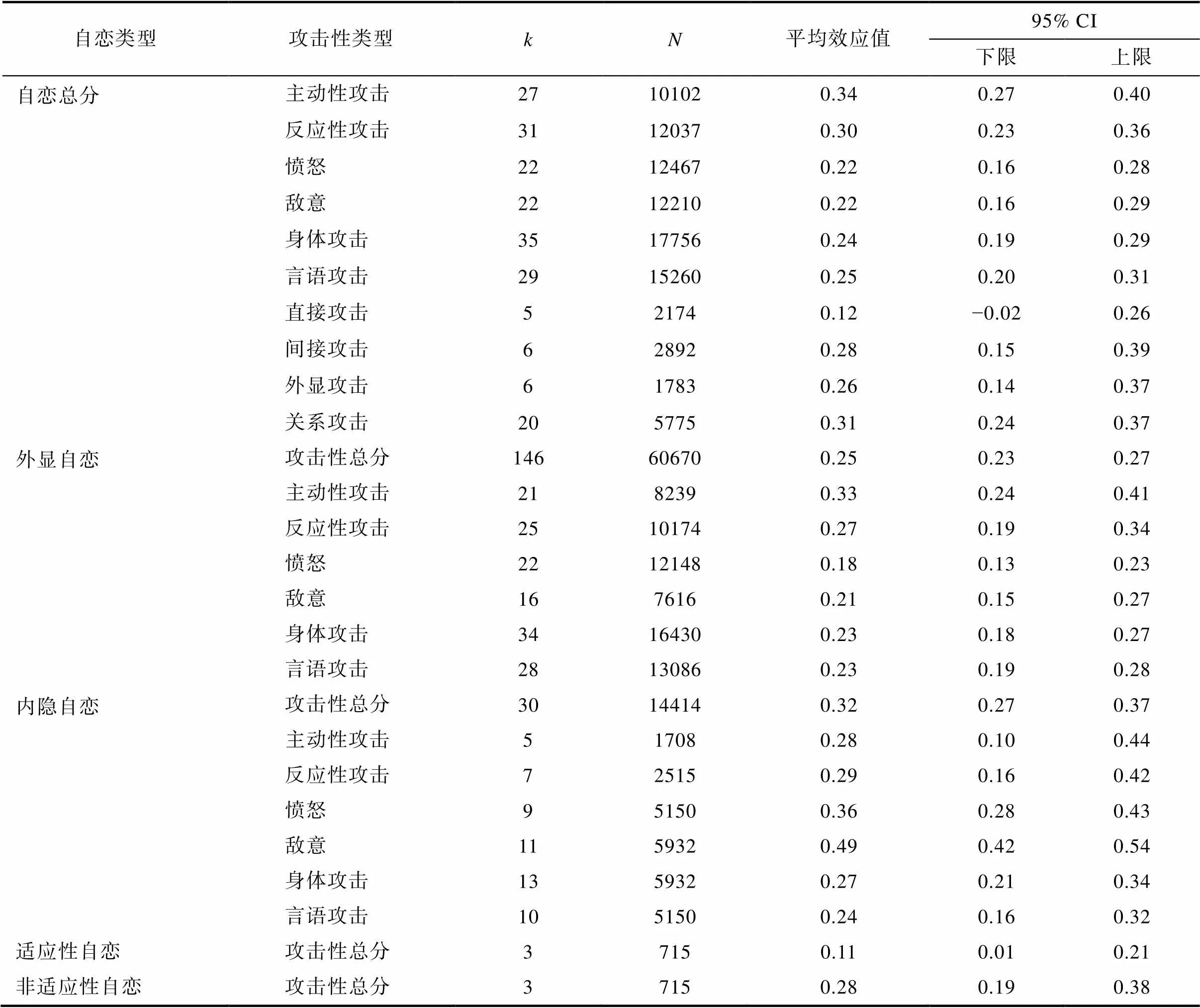

如表3所示:(1)自恋类型(外显自恋vs.内隐自恋)可以显著调节自恋与攻击性总分(Q= 5.46,= 0.019)、愤怒(Q= 31.86,< 0.001)、敌意(Q= 33.09,< 0.001)的关系。相比于外显自恋, 内隐自恋与攻击性总分、愤怒、敌意的相关性更强。自恋类型(外显自恋vs.内隐自恋)不能显著调节自恋和主动性攻击(Q= 0.29,= 0.592)、反应性攻击(Q= 0.132,= 0.716)、身体攻击(Q= 0.97,= 0.325)、言语攻击(Q= 0.014,= 0.907)的关系。(2)自恋类型(适应性自恋vs.非适应性自恋)可以显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系(Q= 5.74,= 0.017)。相比于适应性自恋, 非适应性自恋与攻击性总分的相关性更强。(3)攻击性类型(主动性攻击vs.反应性攻击)不能显著调节自恋总分(Q= 0.90,= 0.342)、外显自恋(Q= 1.15,= 0.284)和内隐自恋(Q= 0.04,= 0.846)与攻击性的关系。(4)攻击性类型(直接攻击vs.间接攻击)不能显著调节自恋和攻击性的关系(Q= 2.66,= 0.103)。(5)攻击性类型(敌意vs.愤怒vs.言语攻击vs.身体攻击)不能显著调节自恋总分(Q= 0.78,= 0.854)、外显自恋(Q= 2.74,= 0.433)与攻击性的关系, 能够显著调节内隐自恋与攻击性的关系(Q= 29.92,< 0.001)。通过配对比较发现, 敌意显著高于愤怒(= 2.57,= 0.010)、身体攻击(= 4.53,0.001)和言语攻击(= 1.61,0.001), 愤怒显著高于言语攻击(= 2.15,= 0.032)。(6)性别和攻击性类型(外显攻击vs.关系攻击)的交互作用对效应值的回归系数不显著(= 0.60),= 0.979。

表2 分类变量调节效应分析结果

表3 自恋不同结构与攻击性不同结构相关系数的元分析

4 讨论

4.1 自恋与攻击性的关系

本研究对检索后获得的121项研究进行了元分析, 结果表明自恋与攻击性存在中等程度的正相关, 与以往的多数研究结果一致, 支持了自恋与攻击性呈正相关的观点。

该结果符合自恋的心理动力学面具模型、动态自我调节加工模型和受威胁的自我主义模型的观点, 自恋者将浮夸的自我感作为面具来掩盖他们的低自尊(Zeigler-Hill & Besser, 2013), 他们除了表现出对自己有较高的评价之外, 还希望他人对自己的价值表现出同样高度的评价(Barry et al., 2003; Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Raskin et al., 1991)。自恋者通过认知和情感的个人内部过程以及人际自我调节策略的动态交互作用来进行自我调节加工, 在寻求评估性反馈的过程中, 不断将任务视为与他人竞争并展示自己优越性的机会; 希望自己比别人更优越, 对他人产生消极的看法和蔑视; 在极端的情况下, 容易产生愤怒, 甚至产生攻击性(Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1998)。因此, 攻击性这种行为层面的极端表现可能在潜在的动机层面起到避免失败、自我保护和自我提升的作用, 是一种保护自我高度认同的方法(Baumeister et al., 2000; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001)。

4.2 调节效应分析

本研究发现男性比越高, 自恋与攻击性的相关性越强, 证实了本研究的假设H1。这表明自恋的男性和女性面对压力情况的反应方式存在社会化差异(Wallace et al., 2012)。这一结果与以往的研究结果不一致(Rasmussen, 2016), Rasmussen的元分析发现, 性别不能显著调节自恋与激发性攻击的关系, 这可能是因为Rasmussen考察的是自恋与激发性攻击的关系, 因此没有纳入无端性攻击以及将激发性攻击和无端性攻击视为同质结构的研究。有研究指出, 在无端性攻击条件下, 男性比女性更具有攻击性, 而挑衅会明显减弱这种性别差异(Bettencourt & Miller, 1996)。

研究结果显示, 自恋报告方式可以显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系, 他人报告的相关系数显著高于自我报告的相关系数, 证实了假设H2a。自恋者缺乏自我洞察力, 认识不到自己性格上的负性方面, 而其他评定者可能会提供个体在自我报告时不愿意承认或无法感知的特征(Cooper et al., 2012)。

另外, 本研究发现攻击性报告方式不能显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系, 与研究假设H2b不一致。虽然受社会期望的影响, 自恋者具有隐藏真实自我的倾向, 但也有研究指出, 自恋者并不担心把自己描绘成攻击性的, 或者他们不认为攻击性一定是不适应的(Ang et al., 2011), 有可能会过度报告自己的攻击行为, 以增强其宏伟的自我形象。另外, 实验室环境不利于观察较为隐蔽的攻击性, 且其他评定者对攻击性的观察仅限于特定的环境, 无法接触到目标个体表现出攻击性的所有情境(Klimstra et al., 2014)。

研究结果显示, 文化不能显著调节自恋和攻击性的关系, 表明自恋与攻击性的关系具有跨文化的一致性, 这与本研究的假设H3不一致。一种可能的解释是, 在个人主义文化背景下, 人们普遍认为使用攻击性有助于实现个人目标, 增加了对攻击性的理解和容忍(Amad et al., 2020)。而在集体主义文化背景下, 个体认为自己是嵌入在集体中的, 高度重视集体的需要(Bergeron & Schneider, 2005), 但攻击性行为违背了合作和人际和谐的目标(Xu et al., 2004), 因此可能得到了抑制。另一种可能的解释是文化的全球化效应, 随着全球经济和社会的发展, 文化呈现出个体主义逐渐增强, 而集体主义相对式微的趋势(黄梓航等, 2018)。因此, 自恋与攻击性的关系受文化的影响较小。

研究结果显示, 自恋类型(外显自恋vs.内隐自恋)可以显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系, 相比于外显自恋, 内隐自恋与攻击性的关系更强, 证实了本研究的假设H4a。外显自恋程度高的个体往往性格较为外向, 情绪弹性较强(Miller & Campbell, 2008), 具有良好的人际关系(Fan et al., 2016)。有研究指出, 与外显自恋相关的高自尊和膨胀的自信对攻击性有缓冲作用(Knight et al., 2018)。相比之下, 内隐自恋者较为内向, 情绪不稳定, 且充满消极情绪(Miller & Campbell, 2008), 人际敏感性较强(Miller et al., 2010), 在其脆弱的自尊受到打击时, 更可能表现出攻击性(Knight et al., 2018)。

研究结果显示, 自恋类型(适应性自恋vs.非适应性自恋)可以显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系, 证实了本研究的假设H4b。表明与适应性自恋相比, 非适应性自恋与攻击性的相关性更强。高适应性自恋个体较少进行消极自我关注(Emmons, 1987), 更加乐观, 甚至有研究指出适应性自恋是抵抗攻击性的保护因素(Washburn et al., 2004)。而非适应性自恋个体更倾向于通过攻击性来获得期望的支配地位(Golmaryami & Barry, 2010)。

我们的研究发现, 无论是外显自恋、内隐自恋还是自恋总分, 攻击性类型(主动性攻击vs.反应性攻击)对自恋与攻击性关系的调节作用均不显著。这表明自恋不仅会诱发反应性攻击,也可能为了获得某些期望的社会地位或关注, 实现对他人的支配, 构建、促进和加强浮夸的自我形象而产生主动性攻击(Muñoz et al., 2013)。Raskin等人(1991)认为敌意、浮夸和支配是相互关联的, 形成了一个连贯的结构系统, 与自恋密切相关, 他们将攻击性视为自恋者个性的核心特征, 而不是源于特定的过程(Bukowski et al., 2009)。

研究结果并未发现攻击性类型(直接攻击vs.间接攻击)能显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系, 没有证实本研究的假设H5b。原因可能是, 本元分析纳入的直接攻击和间接攻击的研究较少, 且Klimstra等人(2014)的研究纳入了同伴评价和教师评价的攻击性, 由于间接攻击具有隐蔽性的特点, 因此他人评价可能很难发现自恋者的间接攻击行为。

研究结果显示, 攻击性类型(身体攻击vs.言语攻击vs.敌意vs.愤怒)能够显著调节内隐自恋与攻击性的关系, 相关程度从高到低分别为敌意、愤怒、身体攻击和言语攻击, 基本证实了本研究的假设H5c。虽然内隐自恋者对他人的评价很敏感, 他们不一定会在身体或言语上直接表达自己的攻击性倾向, 但是他们也存在特权感和忽视他人的倾向(Wink, 1991), 因此, 如果内隐自恋者没有被视为特殊和重要的人, 便容易感到愤怒和敌意(Okada, 2010)。

研究结果并未发现性别和攻击性类型(外显攻击vs.关系攻击)的交互作用显著调节自恋与攻击性的关系。这可能是因为, 本元分析纳入的均为自我报告和他人报告的关系攻击, 但有研究指出采用观察法更可能得到女性比男性倾向于关系攻击的结果, 因为这种研究方法比基于自我、同伴和教师报告的评估方法更不容易因性别刻板印象而产生偏见。另外, 女性比男性更倾向于采用关系攻击这一结论在美国的研究中较为一致, 但不同的文化背景下, 关系攻击的含义和功能不同, 因此在其他文化中这一结论并不一致(Crick et al., 2012)。

4.3 研究不足与展望

本研究的不足:(1)不同亚组的样本量分配不够均匀, 可能会影响元分析的结果; (2)虽然本元分析初步避免了发表偏差的影响, 但是因为语言的限制, 仍有少数研究没有纳入进本研究; (3)本元分析没有说明自恋与其他潜在的不良人格特征一起考虑时的情况, 或许攻击性可以通过自恋与其他特征之间的联系来解释(Rasmussen, 2016; Rasmussen & Boon, 2014)。展望:(1)以往研究中的自恋多采用自我报告的方式, 本元分析发现, 自恋的报告方式可以显著调节自恋和攻击性的关系, 为了获得自恋最准确、最完整的信息, 可以使用多个评定者的数据, 对不同的测量方式进行进一步整合; (2)已有的自恋与攻击性关系研究缺乏对内隐自恋的关注, 本元分析发现, 内隐自恋更可能是攻击性的危险因素, 因此, 以后的研究应加强对内隐自恋的探讨。

5 研究结论

本研究发现自恋与攻击性之间存在中等程度的正相关; 二者关系受性别和自恋报告方式的调节, 但不受攻击性报告方式和文化的调节; 不同类型的自恋与攻击性呈现出不同的相关程度, 内隐自恋与攻击性的相关程度高于外显自恋, 非适应性自恋与攻击性的相关程度高于适应性自恋。

元分析用到的参考文献

Ackerman, R. A., Witt, E. A., Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., & Kashy, D. A. (2011). What does the Narcissistic Personality Inventory really measure?(1), 67–87.

Alexander, M. B., Gore, J., & Estep, C. (2020). How need for power explains why narcissists are antisocial.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0033294120926668

Amad, S. (2015).(Unpublished doctorial dissertation). Cardiff University, UK.

Amad, S., Gray, N. S., & Snowden, R. J. (2020). Self-esteem, narcissism, and aggression: Different types of self-esteem predict different types of aggression.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0886260520905540

An, Z. H., Li, X. C., Chang, R. S, Ma, J. F., & Liang, C. (2021). The influence of covert narcissism on aggressive driving behavior.(2), 109–115.

[安志浩, 李晓晨, 常若松, 马锦飞, 梁超. (2021). 隐性自恋对驾驶员攻击行为的影响.(2), 109–115.]

Ang, R. P., Huan, V. S., Li, X., & Chan, W. T. (2016). Factor structure and invariance of the Reactive and Proactive Aggression Questionnaire in a large sample of young adolescents in Singapore.(6), 883–889.

Ang, R. P., Ong, E. Y. L., Lim, J. C. Y., & Lim, E. W. (2010). From narcissistic exploitativeness to bullying behavior: The mediating role of approval-of-aggression beliefs.(4), 721–735.

Ang, R. P., Tan, K. A., & Mansor, A. T. (2011). Normative beliefs about aggression as a mediator of narcissistic exploitativeness and cyberbullying.(13), 2619–2634.

Ball, L., Tully, R., & Egan, V. (2018). The influence of impulsivity and the Dark Triad on self-reported aggressive driving behaviours., 130–138.

Barnett, M. D., & Powell, H. A. (2016). Self-esteem mediates narcissism and aggression among women, but not men: A comparison of two theoretical models of narcissism among college students., 100–104.

Barry, C. T., Frick, P. J., & Killian, A. L. (2003). The relation of narcissism and self-esteem to conduct problems in children: A preliminary investigation.(1), 139–152.

Barry, C. T., & Kauten, R. L. (2014). Nonpathological and pathological narcissism: Which self-reported characteristics are most problematic in adolescents?(2), 212–219.

Barry, C. T., Loflin, D. C., & Doucette, H. (2015). Adolescent self-compassion: Associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males., 118–123.

Barry, C. T., Pickard, J. D., & Ansel, L. L. (2009). The associations of adolescent invulnerability and narcissism with problem behaviors.(6), 577–582.

Barry, T. D., Thompson, A., Barry, C. T., Lochman, J. E., Adler, K., & Hill, K. (2007). The importance of narcissism in predicting proactive and reactive aggression in moderately to highly aggressive children.(3), 185–197.

Baughman, H. M., Dearing, S., Giammarco, E., & Vernon, P. A. (2012). Relationships between bullying behaviours and the Dark Triad: A study with adults.(5), 571–575.

Baumeister, R. F., Bushman, B. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2000). Self-Esteem, narcissism, and aggression: Does violence result from low self-esteem or from threatened egotism?(1), 26–29.

Baumeister, R. F., Smart, L., & Boden, J. M. (1996). Relation of threatened egotism to violence and aggression: The dark side of high self-esteem.(1), 5–33.

Bergeron, N., & Schneider, B. H. (2005). Explaining cross-national differences in peer-directed aggression: A quantitative synthesis.(2), 116–137.

Besser, A., & Priel, B. (2010). Grandiose narcissism versus vulnerable narcissism in threatening situations: Emotional reactions to achievement failure and interpersonal rejection., 874–902.

Bettencourt, B. A., & Miller, N. (1996). Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A meta-analysis.(3), 422–447.

Bird, B. M., Carre, J. M., Knack, J. M., & Arnocky, S. (2016). Threatening men's mate value influences aggression toward an intrasexual rival: The moderating role of narcissism.(2), 169–183.

Bond, M. H. (2010).. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bukowski, W. M., Schwartzman, A., Santo, J., Bagwell, C., & Adams, R. (2009). Reactivity and distortions in the self: Narcissism, types of aggression, and the functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during early adolescence.(4), 1249–1262.

Burtăverde, V., Chraif, M., Aniţei, M., & Mihăilă, T. (2016). The incremental validity of the Dark Triad in predicting driving aggression., 1–11.

Burton, J. P., & Hoobler, J. M. (2011). Aggressive reactions to abusive supervision: The role of interactional justice and narcissism.(4), 389–398.

Bushman, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence?(1), 219–229.

Bushman, B. J., Baumeister, R. F., Thomaes, S., Ryu, E., Begeer, S., & West, S. G. (2009). Looking again, and harder, for a link between low self-esteem and aggression.(2), 427–446.

Caiozzo, C. N., Houston, J., & Grych, J. (2016). Predicting aggression in late adolescent romantic relationships: A short-term longitudinal study., 237–248.

Carlson, E. N., Vazire, S., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2011). You probably think this paper's about you: Narcissists' perceptions of their personality and reputation.(1), 185–201.

Chen, Y. Y. (2018).(Unpublished master’s thesis). Shanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China.

[陈媛媛. (2018).(硕士学位论文). 陕西师范大学, 西安.]

Cheng, C., Lau, Y., Chan, L., & Luk, J. W. (2021). Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values., 106845.

Cheng, H., Zhang, X. K., Cui, L. Y., & Guo, J. H. (2020). Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Narcissistic Personality Inventory-13.(3), 487–491.

[程浩, 张向葵, 崔力炎, 郭锏壑. (2020). 13条目自恋人格量表中文版的信度效度研究.(3), 487–491.]

Chester, D. S., & DeWall, C. N. (2016). Sound the alarm: The effect of narcissism on retaliatory aggression is moderated by dACC reactivity to rejection.(3), 361–368.

Cooper, L. D., Balsis, S., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2012). Self- and informant-reported perspectives on symptoms of narcissistic personality disorder.(2), 140–154.

Crick, N. R., Casas, J. F., & Mosher, M. (1997). Relational and overt aggression in preschool.(4), 579–588.

Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., & Kawabata, Y. (2012). Relational aggression and gender: An overview. In D. Flannery, A. Vazsonyi, & I. Waldman(Eds.),(pp. 245–259). Cambridge University Press.

Crowe, M. L., Lynam, D. R., Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. D. (2019). Exploring the structure of narcissism: Toward an integrated solution.(6), 1151–1169.

de Zavala, A. G., Cichocka, A., Eidelson, R., & Jayawickreme, N. (2009). Collective narcissism and its social consequences.(6), 1074–1096.

de Zavala, A. G., & Lantos, D. (2020). Collective narcissism and its social consequences: The bad and the ugly.(3), 273–278.

Deng, J. X., Yang, R., Wang, M. C., & Deng, Q. W. (2017). Psychometric properties of Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire in Chinese adolescent.(3), 445–447, 425.

[邓嘉欣, 杨忍, 王孟成, 邓俏文. (2017). 钦佩-竞争自恋量表在中学生群体的信效度检验.(3), 445–447, 425.]

Ding, F. Q., & Zhao, H. Y. (2018). Is the individual subjective well-being of gratitude stronger? A meta-analysis.(10), 1749–1763.

[丁凤琴, 赵虎英. (2018). 感恩的个体主观幸福感更强?——一项元分析.(10), 1749–1763.]

Dinić, B. M., & Wertag, A. (2018). Effects of Dark Triad and HEXACO traits on reactive/proactive aggression: Exploring the gender differences., 44–49.

Dobrucalı, B., & Özkan, T. (2021). What is the role of narcissism in the relationship between impulsivity and driving anger expression?, 246–256.

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency.(4), 328–335.

Edwards, B. D., Warren, C. R., Tubre, T. C., Zyphur, M. J., & Hoffner-Prillaman, R. (2013). The validity of narcissism and driving anger in predicting aggressive driving in a sample of young drivers.(3), 191–210.

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement.(1), 11–17.

Erzi, S. (2020). Dark Triad and schadenfreude: Mediating role of moral disengagement and relational aggression., 109827.

Falkenbach, D. M., Howe, J. R., & Falki, M. (2013). Using self-esteem to disaggregate psychopathy, narcissism, and aggression.(7), 815–820.

Fan, C. Y., Chu, X. W., Zhang, M., & Zhou, Z. K. (2016). Are narcissists more likely to be involved in cyberbullying? Examining the mediating role of self-esteem.(15), 3127–3150.

Fanti, K. A., Demetriou, C. A., & Kimonis, E. R. (2013). Variants of callous-unemotional conduct problems in a community sample of adolescents.(7), 964–979.

Fanti, K. A., & Henrich, C. C. (2015). Effects of self-esteem and narcissism on bullying and victimization during early adolescence.(1), 5–29.

Gai, X. R., Lei, L., Fu, X. J., & Wang, X. C. (2016). The association among narcissism, social status insecurity and cyberbullying: A cross culture study.(6), 73–80.

[盖晓然, 雷雳, 付晓洁, 王兴超. (2016). 中美青少年自恋与网络欺负行为的关系:社会地位不安全感的中介作用.(6), 73–80.]

Gao, X. H., Sun, H. W., Gao, S. H., Bi, J. C., & Qin, F. M. (2014). Narcissism and aggression in impulsive—premeditated violent criminals.(10), 941–943.

[高晓寒, 孙宏伟, 高树宏, 毕建超, 秦峰鸣. (2014). 冲动性-预谋性暴力犯的自恋人格特征与攻击行为.(10), 941–943.]

Geng, Y. G., Sun, Q. B., Huang, J. Y., Zhu, Y. Z., & Han, X. H. (2015). Dirty Dozen and Short Dark Triad: A Chinese validation of two brief measures of the Dark Triad.(2), 246–250.

[耿耀国, 孙群博, 黄婧宜, 朱远征, 韩晓红. (2015). 黑暗十二条与短式黑暗三联征量表:两种黑暗三联征测量工具中文版的检验.(2), 246–250.]

Gewirtz-Meydan, A., & Finzi-Dottan, R. (2018). Narcissism and relationship satisfaction from a dyadic perspective: The mediating role of psychological aggression.(3), 296–312.

Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers., 74–78.

Gnambs, T., & Appel, M. (2018). Narcissism and social networking behavior: A meta-analysis.(2), 200–212.

Golmaryami, F. N., & Barry, C. T. (2010). The associations of self-reported and peer-reported relational aggression with narcissism and self-esteem among adolescents in a residentialsetting.(1), 128–133.

Goodboy, A. K., & Martin, M. M. (2015). The personality profile of a cyberbully: Examining the Dark Triad., 1–4.

Grijalva, E., Newman, D. A., Tay, L., Donnellan, M. B., Harms, P. D., Robins, R. W., & Yan, T. (2015). Gender differences in narcissism: A meta-analytic review.(2), 261–310.

Gumpel, T. P., Wiesenthal, V., & Soderberg, P. (2015). Narcissism, perceived social status, and social cognition and their influence on aggression.(2), 138–156.

Han, X., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, S. S. (2018). Multiple mediating effects of antisocial traits in the relation between self-control and campus bullying among middle school girls.(3), 372–375.

[韩雪, 张野, 张珊珊. (2018). 初中女生反社会行为特质自我控制与校园欺凌关系分析.(3), 372–375.]

Hart, W., Richardson, K., & Tortoriello, G. K. (2018). Revisiting the interactive effect of narcissism and self-esteem on responses to ego threat: Distinguishing between assertiveness and intent to harm.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0886260518777551

Hart, W., Tortoriello, G. K., & Richardson, K. (2018). Provoked narcissistic aggression: Examining the role of de-escalated and escalated provocations.. Advance online publication. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0886260518789901

He, D. (2016).(Unpublished master’s thesis). Central China Normal University, Wuhan.

[何丹. (2016).(硕士学位论文). 华中师范大学, 武汉.]

He, T. (2010).(Unpublished master’s thesis). Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China.

[何婷. (2010).(硕士学位论文). 中山大学, 广州.]

Heinze, P. E., Fatfouta, R., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2020). Validation of an implicit measure of antagonistic narcissism., 103993.

Hofstede, G. 2021-03-01取自https://www.hofstede-insights. com/country-comparison/

Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2010).(Y. Li, & J. M. Sun, Trans.). China Renmin University Press. (Original work published 2005)

[霍夫斯泰德, G., 霍夫斯泰德, G. J. (2010).(李原, 孙健敏译). 中国人民大学出版社.]

Houlcroft, L., Bore, M., & Munro, D. (2012). Three faces of Narcissism.(3), 274–278.

Huang, Z. H., Jing, Y. M., Yu, F., Gu, R. L., Zhou, X. Y., Zhang, J. X., & Cai, H. J. (2018). Increasing individualism and decreasing collectivism? Cultural and psychological change around the globe.(11), 2068–2080.

[黄梓航, 敬一鸣, 喻丰, 古若雷, 周欣悦, 张建新, 蔡华俭. (2018). 个人主义上升, 集体主义式微?——全球文化变迁与民众心理变化.(11), 2068–2080.]

Jonason, P. K., Duineveld, J. J., & Middleton, J. P. (2015). Pathology, pseudopathology, and the Dark Triad of personality., 43–47.

Jones, D. N., & Neria, A. L. (2015). The Dark Triad and dispositional aggression., 360–364.

Juarros-Basterretxea, J., Herrero, J., Escoda-Menéndez, P., & Rodríguez-Díaz, F. J. (2020). Cluster B personality traits and psychological intimate partner violence: Considering the mediational role of alcohol.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0886260520922351

Kalemi, G., Michopoulos, I., Efstathiou, V., Konstantopoulou, F., Tsaklakidou, D., Gournellis, R., & Douzenis, A. (2019). Narcissism but not criminality is associated with aggression in women: A study among female prisoners and women without a criminal record., 21.

Kauten, R., & Barry, C. T. (2014). Do you think I’m as kind as I do? The relation of adolescent narcissism with self- and peer-perceptions of prosocial and aggressive behavior.–, 69–73.

Kauten, R., Barry, C. T., & Leachman, L. (2013). Do perceived social stress and resilience influence the effects of psychopathy-linked narcissism and CU traits on adolescent aggression?(5), 381–390.

Kauten, R. L., Lui, J. H. L., Doucette, H., & Barry, C. T. (2015). Perceived family conflict moderates the relations of adolescent narcissism and CU traits with aggression.(10), 2914–2922.

Kealy, D., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Rice, S. M., & Oliffe, J. L. (2017). Pathological narcissism and maladaptive self-regulatory behaviours in a nationally representative sample of Canadian men., 156–161.

Keene, A. C., & Epps, J. (2016). Childhood physical abuse and aggression: Shame and narcissistic vulnerability., 276–283.

Kerig, P. K., & Stellwagen, K. K. (2010). Roles of callous- unemotional traits, narcissism, and machiavellianism in childhood aggression.(3), 343–352.

Kiire, S. (2017). Psychopathy rather than Machiavellianism or narcissism facilitates intimate partner violence via fast life strategy., 401–406.

Kim, E. J., Namkoong, K., Ku, T., & Kim, S. J. (2008). The relationship between online game addiction and aggression, self-control and narcissistic personality traits.(3), 212–218.

Kircaburun, K., Jonason, P. K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). The Dark Tetrad traits and problematic social media use: The mediating role of cyberbullying and cyberstalking., 264–269.

Klimstra, T. A., Sijtsema, J. J., Henrichs, J., & Cima, M. (2014). The Dark Triad of personality in adolescence: Psychometric properties of a concise measure and associations with adolescent adjustment from a multi-informant perspective., 84–92.

Knight, G. P., Guthrie, I. K., Page, M. C., & Fabes, R. A. (2002). Emotional arousal and gender differences in aggression: A meta-analysis.(5), 366–393.

Knight, N. M., Dahlen, E. R., Bullock-Yowell, E., & Madson, M. B. (2018). The HEXACO model of personality and Dark Triad in relational aggression., 109–114.

Kokkinos, C. M., Baltzidis, E., & Xynogala, D. (2016). Prevalence and personality correlates of Facebook bullying among university undergraduates., 840–850.

Krizan, Z., & Johar, O. (2015). Narcissistic rage revisited.(5), 784–801.

Küfner, A. C. P., Nestler, S., & Back, M. D. (2013). The two pathways to being an (un-)popular narcissist.(2), 184–195.

Kurek, A., Jose, P. E., & Stuart, J. (2019). ‘I did it for the LULZ’: How the dark personality predicts online disinhibition and aggressive online behavior in adolescence., 31–40.

Lau, K. S. L., & Marsee, M. A. (2013). Exploring narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism in youth: Examination of associations with antisocial behavior and aggression.(3), 355–367.

Law, H., & Falkenbach, D. M. (2018). Hostile attribution bias as a mediator of the relationships of psychopathy and narcissism with aggression.(11), 3355–3371.

Li, C. N., Sun, Y., Ho, M. Y., You, J., Shaver, P. R., & Wang, Z. H. (2016). State narcissism and aggression: The mediating roles of anger and hostile attributional bias.(4), 333–345.

Li, D. Y., & Gao, X. M. (2011). Research on the relationship between covert narcissism and aggression.(3), 29–31.

[李东阳, 高雪梅. (2011). 隐性自恋与攻击性的关系研究.(3), 29–31.]

Li, J., Dong, S. H., & Wang, X. T. (2018). Validation of Pathological Narcissism Inventory in Chinese university students.,(2). 249–253.

[李嘉, 董圣鸿, 王小桃. (2018). 病理性自恋量表在中国大学生中的信效度检验.(2). 249–253.]

Liao, X. W., Zhao, L., Liu X. C., & Yang, L. (2015). Mediating effect of hostile cognition between narcissism and dating violence.(4), 686–689.

[廖小伟, 赵琳, 刘新春, 杨丽. (2015). 敌意认知在自恋和恋爱暴力间的中介效应.(4), 686–689.]

Linton, D. K., & Power, J. L. (2013). The personality traits of workplace bullies are often shared by their victims: Is there a dark side to victims?(6), 738–743.

Liu, G., Meng, Y., Pan, Y., Ma, Y., & Zhang, D. (2019). Mediating effect of Dark Triad personality traits on the relationship between parental emotional warmth and aggression.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519877950

Liu, Y. P., Li S. S., He, Y., Wang, D. D. & Yang, B. (2021). Eliminating threat or venting rage? The relationship between narcissism and aggression in violent offenders.,(3), 244–258.

[刘宇平, 李姗珊, 何赟, 王豆豆, 杨波. (2021). 消除威胁或无能狂怒?自恋对暴力犯攻击的影响机制.,(3), 244–258.]

Lobbestael, J., Baumeister, R. F., Fiebig, T., & Eckel, L. A. (2014). The role of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in self-reported and laboratory aggression and testosterone reactivity., 22–27.

Lobbestael, J., Emmerling, F., Brugman, S., Broers, N., Sack, A. T., Schuhmann, T., ... Arntz, A. (2020). Toward a more valid assessment of behavioral aggression: An open source platform and an empirically derived scoring method for using the Competitive Reaction Time Task (CRTT).. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1073191120959757

Lu, F. (2020). The influence of psychological privilege on the aggressive behavior of students in higher vocational colleges.(6), 945–947.

[吕芳. (2020). 心理特权对高等职业院校学生攻击行为的影响.(6), 945–947.]

Lustman, M., Wiesenthal, D. L., & Flett, G. L. (2010). Narcissism and aggressive driving: Is an inflated view of the self a road hazard?(6), 1423–1449.

Maples, J. L., Miller, J. D., Wilson, L. F., Seibert, L. A., Few, L. R., & Zeichner, A. (2010). Narcissistic personality disorder and self-esteem: An examination of differential relations with self-report and laboratory-based aggression.(4), 559–563.

March, E., Grieve, R., Wagstaff, D., & Slocum, A. (2020). Exploring anger as a moderator of narcissism and antisocial behaviour on tinder., 109961.

Marsee, M. A., Silverthorn, P., & Frick, P. J. (2005). The association of psychopathic traits with aggression and delinquency in non-referred boys and girls.(6), 803–817.

Ménard, K. S., Dowgwillo, E. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2018). The role of gender, child maltreatment, alcohol expectancies, and personality pathology on relationship violence among undergraduates.. Advanceonline publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518784589

Meng, Q. Y., & Shi, C. H. (2014). Relationships between family financial difficulty, narcissism and network attacks of middle school students.,(4), 605–607.

[蒙启宇, 施春华. (2014). 家庭经济困难、自恋与中学生网络攻击行为的关系.(4), 605–607.]

Michel, J. S., & Bowling, N. A. (2013). Does dispositional aggression feed the narcissistic response? The role of narcissism and aggression in the prediction of job attitudes and counterproductive work behaviors.(1), 93–105.

Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2008). Comparing clinical and social-personality conceptualizations of narcissism.(3), 449–476.

Miller, J. D., Campbell, W. K., Young, D. L., Lakey, C. E., Reidy, D. E., Zeichner, A., & Goodie, A. S. (2009). Examining the relations among narcissism, impulsivity, and self-defeating behaviors.(3), 761–794.

Miller, J. D., Dir, A., Gentile, B., Wilson, L., Pryor, L. R., & Campbell, W. K. (2010). Searching for a vulnerable dark triad: Comparing Factor 2 psychopathy, vulnerable narcissism, and borderline personality disorder.(5), 1529–1564.

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model.(4), 177–196.

Muñoz, L. C., Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., & Aucoin, K. J. (2013). Emotional reactivity and the association between psychopathy-linked narcissism and aggression in detained adolescent boys.(2), 473–485.

Odaci, H., & Celik, C. B. (2013). Who are problematic internet users? An investigation of the correlations between problematic internet use and shyness, loneliness, narcissism, aggression and self-perception.(6), 2382–2387.

Ojanen, T., Findley, D., & Fuller, S. (2012). Physical and relational aggression in early adolescence: Associations with narcissism, temperament, and social goals.(2), 99–107.

Okada, R. (2010). The relationship between vulnerable narcissism and aggression in Japanese undergraduate students.(2), 113–118.

Öngen, D. E. (2010). Relationships between narcissism and aggression among non-referred Turkish university students., 410–415.

Onishi, A., Kawabata, Y., Kurokawa, M., & Yoshida, T. (2012). A mediating model of relational aggression, narcissistic orientations, guilt feelings, and perceived classroom norms.(4), 367–390.

Pabian, S., de Backer, C. J. S., & Vandebosch, H. (2015). Dark Triad personality traits and adolescent cyber-aggression., 41–46.

Pailing, A., Boon, J., & Egan, V. (2014). Personality, the Dark Triad and violence., 81–86.

Pechorro, P., Hidalgo, V., Nunes, C., & Jiménez, L. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Antisocial Process Screening Device.(16), 1856–1872.

Przepiorka, A. M., Blachnio, A., & Wiesenthal, D. L. (2014). The determinants of driving aggression among Polish drivers., 69–80.

Raskin, R., Novacek, J., & Hogan, R. (1991). Narcissistic self-esteem management.(6), 911–918.

Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity.(5), 890–902.

Rasmussen, K. R. (2016). Entitled vengeance: A meta-analysis relating narcissism to provoked aggression.(4), 362–379.

Rasmussen, K. R., & Boon, S. D. (2014). Romantic revenge and the Dark Triad: A model of impellance and inhibition., 51–56.

Reidy, D. E., Foster, J. D., & Zeichner, A. (2010). Narcissism and unprovoked aggression.(6), 414–422.

Reidy, D. E., Zeichner, A., Foster, J. D., & Martinez, M. A. (2008). Effects of narcissistic entitlement and exploitativeness on human physical aggression.(4), 865–875.

Rhodewalt, F., Madrian, J. C., & Cheney, S. (1998). Narcissism, self-knowledge organization, and emotional reactivity: The effect of daily experiences on self-esteem and affect.(1), 75–87.

Rhodewalt, F., & Morf, C. C. (1995). Self and interpersonal correlates of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory: A review and new findings.(1), 1–23.

Rhodewalt, F., & Morf, C. C. (1998). On self-aggrandizement and anger: A temporal analysis of narcissism and affective reactions to success and failure.(3), 672–685.

Sagioglou, C., & Greitemeyer, T. (2016). Individual differences in bitter taste preferences are associated with antisocial personality traits., 299–308.

Seah, S. L., & Ang, R. P. (2008). Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in Asian adolescents: Relations to narcissism, anxiety, schizotypal traits, and peer relations.(5), 553–562.

Shi, D. (2020).(Unpublished master’s thesis). Zhengzhou University.

[史丹. (2020).(硕士学位论文). 郑州大学.]

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Chen, S., Saklofske, D. H., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2016). Perfectionism and narcissism: A meta-analytic review., 90–101.

Song, J., Cai, Q., Hu, X. L., & Chen, X. (2013). The Relationships among university students’ overt, covert narcissism, and trait aggression.(5), 746–749.

[宋健, 蔡晴, 胡兴林, 陈晓. (2013). 大学生显性自恋、隐性自恋与特质攻击的关系研究.(5), 746–749.]

Stuart, J., & Kurek, A. (2019). Looking hot in selfies: Narcissistic beginnings, aggressive outcomes?(6), 500–506.

Tanrikulu, I., & Erdur-Baker, Ö. (2019). Motives behind cyberbullying perpetration: A test of Uses and Gratifications Theory.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518819882

Tetreault, C., Bates, E. A., & Bolam, L. T. (2018). How dark personalities perpetrate partner and general aggression in Sweden and the United Kingdom.. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0886260518793992

Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., Stegge, H., & Olthof, T. (2008). Trumping shame by blasts of noise: Narcissism, self-esteem, shame, and aggression in young adolescents.(6), 1792–1801.

Thomaes, S., Stegge, H., Bushman, B. J., Olthof, T., & Denissen, J. (2008). Development and validation of the Childhood Narcissism Scale.(4), 382–391.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2003). "Isn't it fun to get the respect that we're going to deserve?" Narcissism, social rejection, and aggression.(2), 261–272.

van Geel, M., Goemans, A., Toprak, F., & Vedder, P. (2017). Which personality traits are related to traditional bullying and cyberbullying? A study with the Big Five, Dark Triad and sadism., 231–235.

Vize, C. E., Collison, K. L., Crowe, M. L., Campbell, W. K., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2019). Using dominance analysis to decompose narcissism and its relation to aggression and externalizing outcomes.(2), 260–270.

von Collani, G., & Werner, R. (2005). Self-related and motivational constructs as determinants of aggression: An analysis and validation of a German version of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire.(7), 1631–1643.

Wallace, M. T., Barry, C. T., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Green, B. A. (2012). Locus of control as a contributing factor in the relation between self-perception and adolescent aggression.(3), 213–221.

Washburn, J. J., McMahon, S. D., King, C. A., Reinecke, M. A., & Silver, C. (2004). Narcissistic features in young adolescents: Relations to aggression and internalizing symptoms.(3), 247–260.

Webster, G. D., Gesselman, A. N., Crysel, L. C., Brunell, A. B., Jonason, P. K., Hadden, B. W., & Smith, C. V. (2016). An actor–partner interdependence model of the Dark Triad and aggression in couples: Relationship duration moderates the link between psychopathy and argumentativeness., 196–207.

Westhead, J., & Egan, V. (2015). Untangling the concurrent influences of the Dark Triad, personality and mating effort on violence., 222–226.

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism.(4), 590–597.

Xu, Y., Farver, J. A., Schwartz, D., & Chang, L. (2004). Social networks and aggressive behaviour in Chinese children.(5), 401–410.

Yang, C. C., Li, C. N., Wang, Z. H., & Bian, Y. F. (2016). The mediational roles of perceived threat, anger, and hostile attribution bias between state narcissism and aggression.(2), 236–245.

[杨晨晨, 李彩娜, 王振宏, 边玉芳. (2016). 状态自恋与攻击行为——知觉到的威胁、愤怒情绪和敌意归因偏差的多重中介作用.(2), 236–245.]

Yang, S. D., Zhu, Q. Z., Zhu, H. M., Mo, Q. M., Tao, J. F., & Guo, L. (2017). Relationship between narcissism and aggression among Macau and mainland college students.(3), 374–377.

[杨松达, 朱麒臻, 朱会明, 莫庆民, 陶剑飞, 郭丽. (2017). 澳门内地大学生自恋人格与攻击性关联分析.(3), 374–377.]

Zeigler-Hill, V., & Besser, A. (2013). A glimpse behind the mask: Facets of narcissism and feelings of self-worth.(3), 249–260.

Zerach, G. (2016). Pathological narcissism, cyberbullying victimization and offending among homosexual and heterosexual participants in online dating websites., 292–299.

Zhai, Y. Y. (2012).(Unpublished master’s thesis). Shanxi Normal University, Linfen, China.

[翟云彦. (2012).(硕士学位论文). 山西师范大学, 临汾.]

Zhang, B. Q. (2012).(Unpublished master’s thesis). Hangzhou Normal University, China.

[张宝强. (2012).(硕士学位论文). 杭州师范大学.]

Zhang, G. P., & Lan, S. (2020). The influence mechanism of social exclusion on college students' aggressive behavior: The internal mechanism of anxiety and narcissistic personality,(3), 95–100.

[张桂平, 兰珊. (2020). 社会排斥对大学生攻击行为的影响机制——焦虑情绪和自恋型人格的内在机理.(3), 95–100.]

Zhang, H., & Zhao, H. (2020). Dark personality traits and cyber aggression in adolescents: A moderated mediation analysis of belief in virtuous humanity and self-control., 105565.

Zhang, T. (2019).(Unpublished master’s thesis). Wuhan University, China.

[张彤. (2019).(硕士学位论文). 武汉大学.]

Zheng, Y. N., Liao H. Y., & Liu, D. X. (2020). Current situation and relationship between aggressive behavior and Dark Triad of medical students in a medical university in GanZhou City.(10), 89–93.

[郑亚楠, 廖慧云, 刘地秀. (2020). 赣州市某医学院校医学生攻击行为与黑暗三联征现况及相互关系.(10), 89–93.]

Relationship between narcissism and aggression: A meta-analysis

ZHANG Lihua, ZHU He

(School of Psychology, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian 116029, China)

Aggression and violence are prevalent public health problems, tremendously harming individuals, families and society. Supposedly, low self-esteem is an important cause of aggression. However, some researchers have suggested that aggression may be attributable to threatened egoism, that is, the inflated and narcissistic view of self that is threatened, rather than low self-esteem itself. Numerous studies have explored the relationship between narcissism and aggression. However, these results appear somewhat inconsistent in different studies. Therefore, this meta-analysis was conducted to explore the strength and moderators of the relationship between narcissism and aggression.

We included Chinese and English literature from 1965 to 2021. A total of 177 independent effect sizes (121 studies, 73687 participants) were found within the criteria of the meta-analysis. On the basis of the characteristics of studies, we selected the random-effects model. After coding the data, independent effect sizes were analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.3 program.

The results of the funnel plot and Egger test showed no publication bias. Results showed a significant positive correlation (= 0.27, 95% CI [0.25, 0.29]) between narcissism and aggression. Additionally, the moderation analyses revealed that the strength of the relationship was moderated by gender and report modality of narcissism, but not by report modality of aggression and culture. Meanwhile, different types of narcissism related differently to aggression, in that covert narcissism was more positively correlated with aggression compared with overt narcissism, and maladaptive narcissism was more positively correlated with aggression compared with adaptive narcissism.

Based on the meta-analysis, narcissism and aggression were closely related. The mechanisms of aggression must be identified to develop effective prevention and intervention strategies to alleviate the public health problems caused by aggression. Future research could: (1) The present study found that report modality of narcissism plays a moderating role in the relationship between narcissism and aggression. Therefore, to gain insights into the reporters’ bias and obtain accurate and complete information regarding narcissism, the data of multiple reporters can be employed. (2) Overt narcissism and covert narcissism are distinct structures, and the existing studies on the relationship between narcissism and aggression have paid less attention to covert narcissism. The present study found that covert narcissism is more likely to be a risk factor for aggression than overt narcissism. Therefore, future research could strengthen the exploration of covert narcissism.

narcissism, aggression, meta-analysis

2020-12-19

* 辽宁省社会科学规划基金项目(L19BSH004)资助。

张丽华和朱贺为本文的共同一作。

B848

张丽华, E-mail: zhanglihua7@163.com