Two-point compression ultrasonography: Enough to rule out lower extremity deep venous thrombosis?

Ralphe Bou Chebl, Nader El Souki, Mirabelle Geha, Imad Majzoub, Rima Kaddoura, Hady Zgheib

Department of Emergency Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut 1107 2020, Lebanon

KEYWORDS: Lower extremity; Deep venous thrombosis; Emergency department; Two-point compression ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity.[1,2]The annual incidence of lower extremity DVT in the USA is approximately 300,000 to 600,000 cases per year.[3]DVTs in the thigh veins are classified as proximal, whereas calf vein DVTs are referred to as distal. Venous thrombosis has been associated with genetic as well as acquired risk factors such as malignancy and immobility.[4,5]Contrast venography has been replaced by duplex sonography as the first-line imaging modality.[6-8]Its sensitivity and specificity for proximal DVTs are 100% and 98%, respectively, while for distal DVTs they drop to 94% and 75%, respectively.[9-11]

In emergency department (ED) settings, pointof-care two-point compression ultrasonography is increasingly being used.[12]This technique has been quickly adopted since it takes a shorter time than wholeleg ultrasound, as it only focuses on the two highest probability sites of DVTs (the popliteal and common femoral veins), and has been found to be as sensitive as whole-leg ultrasonography. A study by Bernardi[13]compared serial two-point compression ultrasound with D-dimer to whole-leg ultrasound, and found that both techniques had similar detection rates and sensitivities in identifying patients with DVT. The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) published an ultrasound imaging compendium that described a point-of-care compression technique for the detection of proximal lower extremity DVT. This technique evaluates thrombosis in the common femoral vein and popliteal vein.[14-17]However, a study by Adhikari et al[18]showed that among 362 patients who had DVT, 6.3% had an isolated thrombus in proximal lower extremity veins diff erent from the common femoral and popliteal veins. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to further validate the prevalence and distribution of venous thrombi isolated to lower extremity veins, other than common femoral and popliteal veins, in patients with clinical symptoms suggestive of DVT. We hypothesize that there is a signifi cant prevalence of DVTs isolated to proximal lower extremity veins other than common femoral and popliteal veins.

METHODS

Study design

This single-center retrospective study aimed to determine the prevalence and distribution of venous thrombi isolated to proximal lower extremity veins other than common femoral and popliteal veins using ultrasonography. The inclusion criteria were patients presenting to the ED of a tertiary care hospital between January 2014 and August 2018 who underwent a lower extremity duplex exam. Patient consent was waived since this was a retrospective chart review study without any patient identifi ers. Two research assistants were in charge of reviewing the charts and abstracting the data. Multiple sessions were held with the principal investigator in order to standardize the data abstraction process. In case of disagreement between abstractors, the principal investigator reviewed the chart for a final decision. The retrieved information, including the clinical presentation, laboratory and imaging results, was obtained using the hospital’s medical record. Lower extremity duplex exams are assigned a standardized billing code by the hospital’s medical record department. Patients’ encounters were filtered by an experienced data user using the billing code.

Study population

All adult patients who underwent a lower extremity duplex ultrasound during our study period were obtained. Patients who had the duplex ultrasound in the ED for suspected lower extremity DVT were included. All ultrasounds were performed by vascular sonographers and read by board-certified vascular surgeons. All ultrasound examinations were done using a uniform protocol that started with venous compression every 2 cm in the transverse plane of the common femoral. The great saphenous vein was examined at the saphenofemoral junction. The deep femoral vein was then examined at the confluence with the femoral vein. Following that, the femoral, popliteal, and posterior tibial and peroneal veins were imaged. The study group included patients with documented DVT on ultrasound. Exclusion criteria included patients with a normal duplex scan, pregnant patients, patients without a documented lower extremity duplex ultrasound report, or a duplex done outside the ED. Patients were stratified into two groups based on DVT location. The isolated DVT group that would have been missed by two-point compression ultrasound, included all patients with DVTs in the deep or isolated femoral vein. The two-point compression group included all patients with DVT locations detected by a two-point compression test.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the prevalence and distribution of isolated proximal lower extremity deep venous thrombi in locations other than the common femoral and popliteal veins. Secondary outcomes included the difference in patient demographics, DVT risk factors, symptoms at presentation, and D-dimer levels between the isolated DVT group and the two-point compression group.

Data collection

The following data were retrieved from the patient’s chart: demographic data (age, gender, smoking status, allergy, alcohol, past medical history, recent surgery, recent travel history, and pregnancy), characteristics (symptoms at presentation and D-dimer), and location of the thrombus. The following locations of venous thrombi were to be identified: common femoral vein, femoral vein, deep femoral vein, popliteal vein, femoral-deep femoral veins, common femoral-femoral veins, common femoral-femoral-deep femoral veins, common femoralfemoral-deep femoral-popliteal vein, common femoral- femoral-popliteal veins, common femoral-deep femoralpopliteal veins, femoral-popliteal veins, deep femoralpopliteal veins, calf-proximal veins, and calf veins.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata MP version 13.0 (College Station, USA). Frequency and percentages were used to describe categorical variables, while mean and standard deviation (SD) were used for continuous ones. The association between different variables and DVTs was determined using Pearson’s Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, while the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney rank-sum test was used for continuous ones. A signifi cance level of 0.05 was used.

RESULTS

A total of 2,507 patients received a lower extremity duplex ultrasound during the study period. Of those, 379 (15%) were included in the study. A total of 2,128 patients were excluded: 2,122 patients were excluded because they had a normal duplex ultrasound exam, six patients were excluded because there were no lower extremity duplex ultrasound reports.

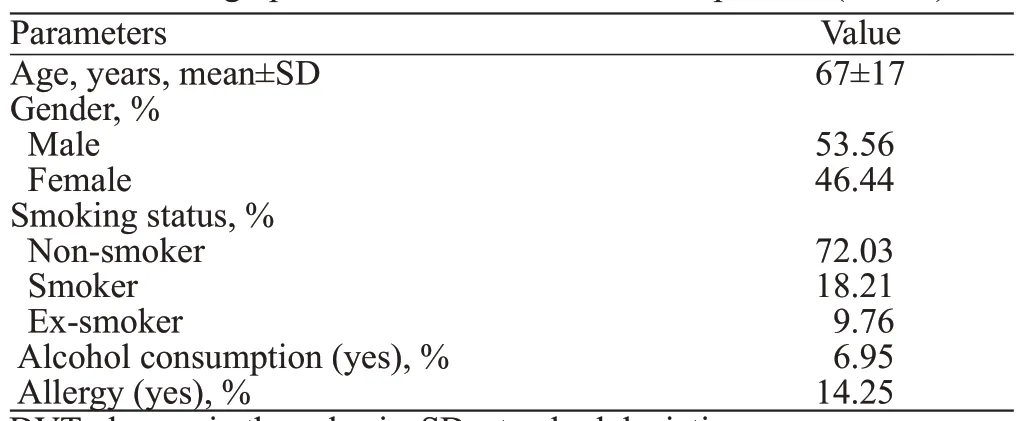

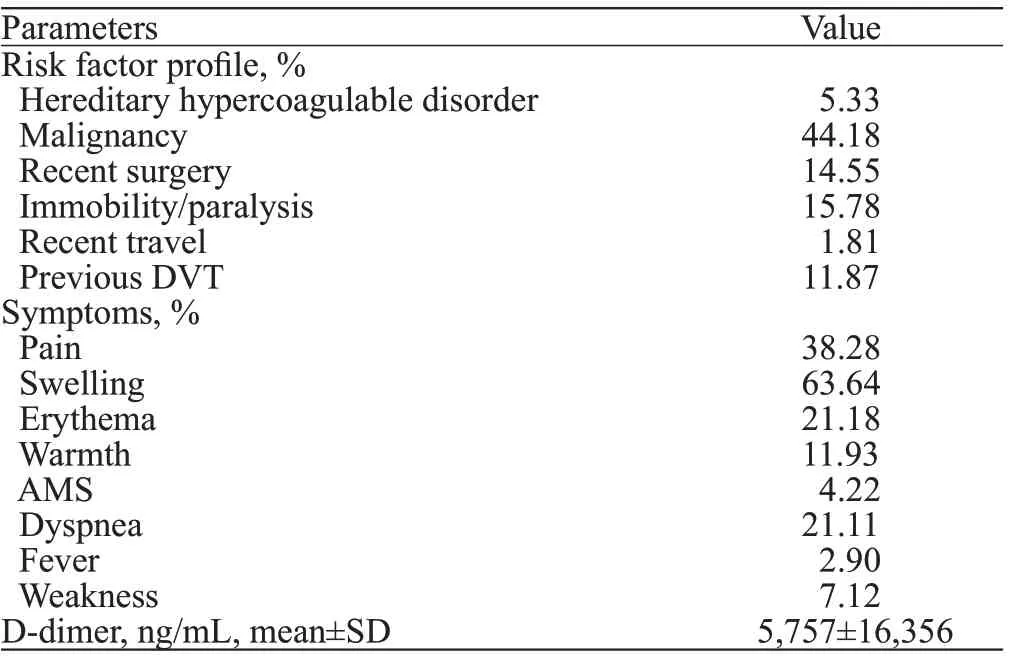

The mean age of our population was 67±17 years, with 53.56% of our patients being males. The vast majority of patients were non-smokers (72.03%), followed by smokers (18.21%) and ex-smokers (9.76%) (Table 1). About 44.18% of our patients had a history of active malignancy, 15.78% had prolonged immobility/paralysis, 14.55% had recent surgery, and 5.33% had hereditary hypercoagulable disorder. All the risk factors are summarized in Table 2.

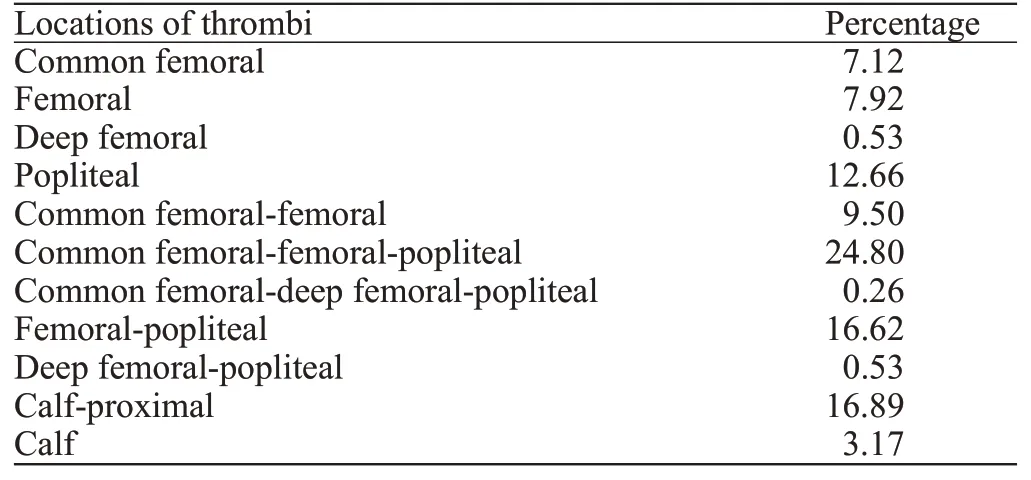

The most common location for deep venous thrombi was the common femoral-femoral-popliteal veins (24.80%), followed by calf-proximal veins (16.89%), femoral-popliteal veins (16.62%), and isolated popliteal veins (12.66%). The percentages of isolated thrombi to the femoral vein and deep femoral-popliteal vein were 7.92% and 0.53%, respectively. These results are presented in Table 3.

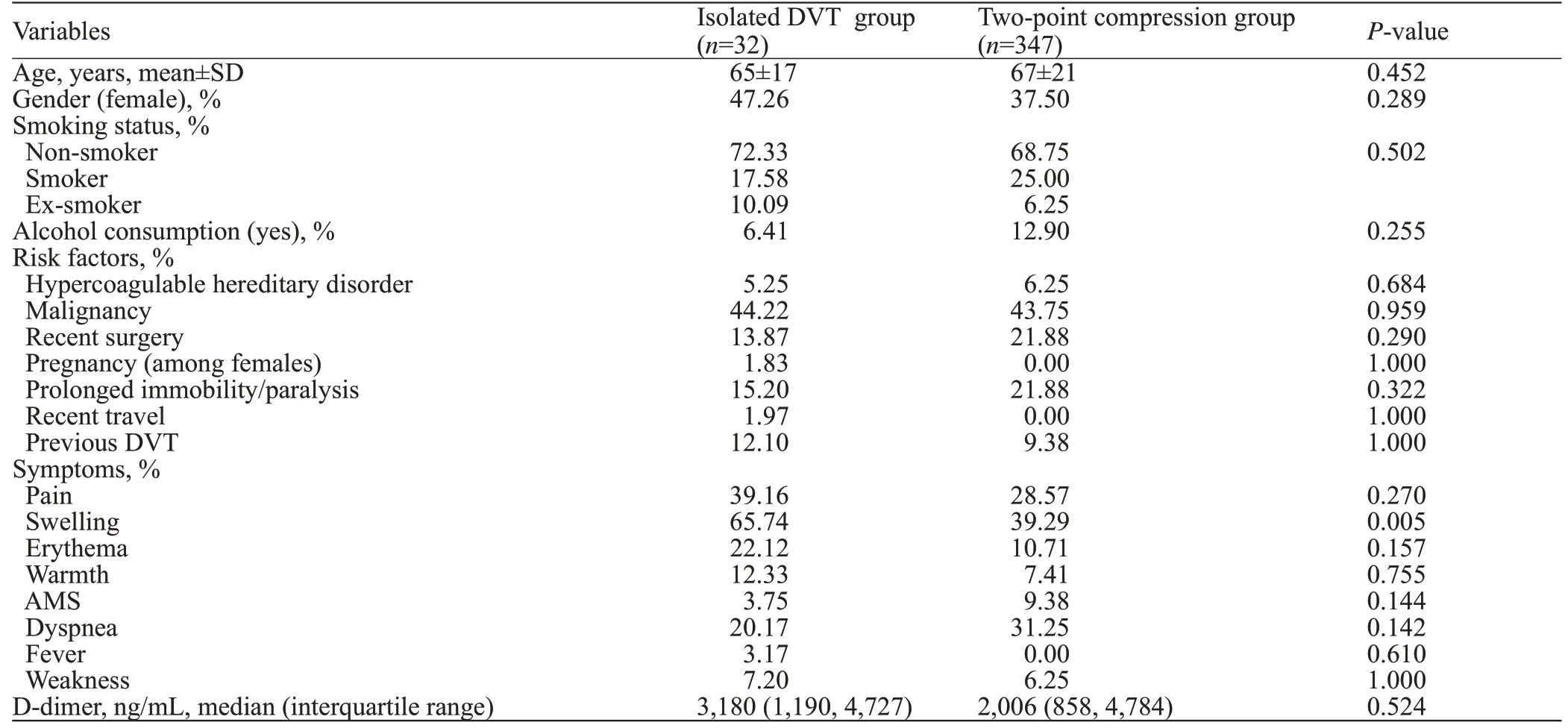

The most common symptom of DVT was lower extremity swelling (63.64% of patients), followed by pain (38.28%) and erythema (21.11%). The mean D-dimer level among all patients was 5,757 ng/mL (Table 2). When stratified into the two groups of isolated DVT and twopoint compression DVT, we found that the isolated DVT patients were younger (65±17 years vs. 67±21 years), and had a higher percentage of female patients (47.26% vs. 37.50%) (Table 4). Non-smokers represented the majority of patients in both groups (72.33% in the isolated group and 68.75% in the two-point compression group). There were a similar number of patients with malignancies in both groups (44.22% vs. 43.75%) as well as patients with hereditary hypercoagulable disorders (5.25% vs. 6.25%). However, there was a lower percentage of patients with a history of recent surgery in the isolated group (13.87% vs. 21.88%,P=0.290), as well as a lower percentage of patients with prolonged immobility or paralysis (15.20% vs. 21.88%) as compared to the two-point compression group. In both groups, the most common symptom was swelling; but it was significantly higher in the isolated group when compared to the two-point compression group (65.74% vs. 39.29%,P<0.05). Pain, erythema, and warmth were also higher but not statistically signifi cant in the isolated group (39.16% vs. 28.57%; 22.12% vs. 10.71%; 12.33% vs. 7.41%, respectively). However, dyspnea and altered mental status (AMS) were lower in the isolated group as compared to the two-point compression group (20.17% vs. 31.25%; 3.75% vs. 9.38%, respectively). The median D-dimer level was higher in the two-point compression group (3,180 ng/mL vs. 2,006 ng/mL,P=0.524).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of all DVT patients (n=379)

Table 2. Risk factor profi le, symptoms at presentation and D-dimer levels of all DVT patients

Table 3. Spatial distribution of thrombi among all patients (n=379)

Table 4. Comparison of demographics, risk factors, symptoms, and D-dimer level between the isolated DVT group and the two-point compression group

DISCUSSION

The results of our study showed that 8.45% of all proximal DVTs were isolated to the femoral or deep femoral veins. This further validated the results found by Adhikari et al,[18]which showed that 6.3% of patients had isolated DVTs. One of the earliest studies conducted by Cogo et al[19]looked at a series of venograms and found that none of the patients with clinically suspected venous thrombosis had isolated thrombi in the femoral vein. Following that study, physicians began to look at the role of a limited two-point compression duplex scan in the ED, focusing on the two areas of highest prevalence, the saphenofemoral junction and the popliteal vein. Following that, several studies compared two-point compression to a full vascular examination and found the results to be highly comparable.[14-17]This was followed by the ACEP adoption and publication of this technique in its ultrasound guidelines.

A recent meta-analysis by Lee et al[20]compared a two-point compression ultrasound strategy to a threepoint compression ultrasound strategy and found that both methods had very similar sensitivity and specifi city (sensitivity [0.91, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.68-0.98,P=0.86] and specificity [0.98, 95%CI0.96-0.99,P=0.60] for the two-point; sensitivity [0.90, 95%CI0.83-0.95] and specifi city [0.95, 95%CI0.83-0.99] for the three-point compression). Furthermore, the authors found that the adjusted false-negative rates were around 4% for each ultrasound strategy. However, they did not state what areas were most commonly missed by the two-point compression, and none of the studies directly compared both techniques. The results of our study in addition to the Adhikari’s study show that a significant percentage of DVTs are being missed by the two-point lower extremity duplex ultrasound in the ED. It is our belief that the exclusion of the femoral vein imaging with two-point compression ultrasonography would lead to missing a signifi cant number of isolated lower-extremity thrombi. These results support the use of extended pointof-care compression ultrasonography. Therefore, it is our recommendation that the femoral vein and deep femoral vein are added to the common femoral and popliteal veins when checking for suspected DVT using lower extremity duplex ultrasound in patients presenting to the ED with suspected DVT. While it might require additional time to evaluate the proximal deep femoral veins, we believe that missing 8.54% of patients with DVTs can compromise the patient’s health and lead to a poor outcome. In fact, a study by Zuker-Herman et al[21]showed that three-point compression ultrasound had a signifi cantly higher sensitivity (91% vs. 83%) and similar specificity (98%) in diagnosing lower extremity DVT in the ED, when compared to two-point compression ultrasound.

Finally, the demographic characteristics, risk factor profile, and D-dimer level were similar and not statistically diff erent, regardless of the thrombus location. However, it is important to note that immobilized patients and patients with recent surgeries were more likely to have an isolated proximal DVT. Emergency physicians should be aware of this finding and have a high index of suspicion in these patients. The most common signs and symptoms were swelling, pain, erythema, warmth, and weakness, which was similar to what was reported in the literature.[22,23]A significantly high and abnormal levels of D-dimer were found in this study population when compared to the normal reference range. This is consistent with the literature. For instance, a study by Hasegawa et al[24]showed a significantly higher level of D-dimer in patients with DVT as compared to healthy individuals. However, there was no difference in D-dimer level or symptomatic presentations between the isolated DVT group and the two-point compression groups. Therefore, physical examination findings and laboratory results are not enough to favor a limited twopoint compression exam over a more detailed exam. As mentioned above, the majority of patients with DVT were non-smokers. Smoking is a well-proved risk factor for atherosclerosis, but its association with DVT remains controversial. Several prospective studies showed smoking as an independent risk factor;[25,26]while others reported no significant relationship between the two.[27,28]A meta-analysis conducted by Cheng et al[29]showed a slightly increased relative risk for ever smokers compared to non-smokers (risk ratio [RR] 1.17, 95%CI1.09-1.25,P<0.001).

Limitations

This study was limited by its retrospective nature, and as such, it was subject to the inherent ascertainment bias of a chart review. The data extractors were not blinded to the study hypothesis. However, in order to minimize the bias of data extraction, several meetings were conducted with the primary investigator in order to ensure a standardized data collection. The study was limited by its small sample size, which may affect the significance of the results. The sample size was chosen according to the accessibility of the electronic medical record. Furthermore, this study was a singlecentered study in a tertiary care center, and as such, the results may not be generalizable to other settings. It was important to note that the location of the thrombus was determined from the exams read by the vascular surgeon. It was possible that the vascular surgeons did not precisely code the distribution of thrombus, resulting in either overestimation or underestimation of distribution of thrombi in some cases. Furthermore, the reports generated by the sonographer did not specify the exact distance of the clot from the common femoral vein bifurcation, which would have been benefi cial to know. Finally, this study did not compare a three-point compression strategy to a two-point ultrasound strategy, and therefore we cannot comment on which strategy is better.

CONCLUSIONS

The percentage of thrombi isolated to lower extremity veins other than the common femoral and popliteal veins, i.e., the femoral and deep femoral veins, constitutes 8.45% of DVTs and is therefore highly signifi cant. As a result, these thrombi are missed during routine bedside two-point lower extremity duplex ultrasound done in the ED, leading to a compromise in patient’s healthcare and outcome. Therefore, we recommend the addition of the femoral and deep femoral veins to the common femoral and popliteal veins when looking for DVT in the ED using lower extremity duplex ultrasound.

Funding:This study did not receive any funding.

Ethical approval:Approval from the hospital’s institutional review board (IRB BIO-2018-0480) was obtained before starting the study.

Conflicts of interests:The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributors:HZ, RBC, and IM: conception and design of the study; MG, NES, RBC, and RK: acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data; RBC, HZ, IM, NES: drafting the manuscript; RBC, IM, and HZ: revision of manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed substantially to its revision. HZ and RBC took responsibility for the paper as a whole.

World journal of emergency medicine2021年4期

World journal of emergency medicine2021年4期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Fatal and non-fatal injuries due to suspension trauma syndrome: A systematic review of defi nition, pathophysiology, and management controversies

- Saddle pulmonary embolism is not a sign of high-risk deterioration in non-high-risk patients: A propensity score-matched study

- High-fl ow nasal cannula oxygen therapy and noninvasive ventilation for preventing extubation failure during weaning from mechanical ventilation assessed by lung ultrasound score: A single-center randomized study

- Comparison of clinical characteristics in patients with coronavirus disease and infl uenza A in Guangzhou, China

- Development of septic shock and prognostic assessment in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease outside Wuhan, China

- Protective eff ect of extracorporeal membrane pulmonary oxygenation combined with cardiopulmonary resuscitation on post-resuscitation lung injury