Systematic review of existing guidelines for NAFLD assessment

Filippo Monelli, Francesco Venturelli, Lisa Bonilauri, Elisa Manicardi, Valeria Manicardi, Paolo Giorgi Rossi, Marco Massari, Guido Ligabue, Nicoletta Riva, Susanna Schianchi, Efrem Bonelli, Pierpaolo Pattacini, Maria Chiara Bassi, Giulia Besutti

1Clinical and Experimental Medicine PhD program, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena 41121, Italy.

2Radiology Unit, Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Laboratory Medicine, AUSL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123,Italy.

3Epidemiology Unit, AUSL- IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

4Diabetes Clinic, AUSL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

5Infectious Diseases Unit, AUSL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

6Department of Radiology, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena 41121, Italy.

7Internal Medicine, AUSL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

8Medical Library, AUSL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia 42123, Italy.

Abstract

Keywords: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, liver fibrosis, liver biopsy, noninvasive diagnosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with metabolic disorders such as obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypertension, and dyslipidemia[1]. NAFLD is a continuum of clinical entities, from simple hepatic steatosis to inflammatory non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). In this process there is an increasing risk of developing liver fibrosis and cirrhosis[2], ultimately leading to a higher risk of end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. NAFLD is characterized by an accumulation of triglycerides in lipid droplets inside the hepatocytes[3]in the absence of other causes of liver injury[4], including excessive alcohol intake. The transition from NAFLD to NASH can be assessed accurately only with histology on liver biopsy samples. Histologically, NAFLD is defined by the presence of steatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes[5], with no evidence of cellular injury such as hepatocyte ballooning. NASH, instead, is characterized by the presence of steatosis and the presence of inflammation and hepatocytic injury, which is frequently associated with liver fibrosis[6].

The incidence of NAFLD is increasing worldwide and is currently the most common liver disease[7]. Its global prevalence of 25% varies across different geographical areas, from 14% in Africa to 32% in the Middle East[8]. The distribution of NAFLD appears to be linked to socioeconomic status, with a higher prevalence in industrialized countries[9], although incidence is increasing in every social and ethnic group[10].

The high prevalence and the increased risk of developing severe liver diseases, including hepatocellular carcinoma, make NAFLD a major health issue worldwide, and thus a potentially considerable burden on health care systems. Among the questions associated with this evolving epidemiology, two impact the management of NAFLD patients the most. The first is how to select patients at high risk of progression to severe disease; the second concerns which tests to perform on these patients, including noninvasive examinations and liver biopsy. This second question is especially important given that the very first drugs to treat NASH are in phase II and III trials and are expected to be accepted soon for clinical use[11,12].

In recent years, many national and international guidelines have been developed to provide recommendations on how to select patients to be referred for diagnosis and which procedure should be used for the assessment of NAFLD. The aim of this systematic review was to produce a comprehensive and updated review of existing guidelines focusing on NAFLD diagnosis and staging.

METHODS

Guideline eligibility

Inclusion criteria were: (1) guidelines on NAFLD assessment intended for clinical use on humans; (2)English language; and (3) publication date from January 2010 to August 2020. Exclusion criteria were: (1)outdated guidelines (i.e., guidelines for which an updated version is included in the review); and (2) review of guidelines. Practice guidance released by national or international associations, which are different from guidelines and report statements instead of recommendations, were formally excluded from guideline selection, but were used to integrate and/or update recommendations extracted from formal guidelines released by the same association.

Guideline search and selection

A systematic review of the literature was carried out according to PRISMA guidelines[13]. MEDLINE,Embase, and CINAHL databases were explored focusing on guidelines on NAFLD diagnosis and management produced in the last 10 years. The search string originally used for MEDLINE and then adapted to every database was: ["Fatty Liver" (Mesh) OR "Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease" (Mesh) OR“fatty liver” OR “NAFLD” OR “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease”].

The literature search was completed by searching relevant websites such as Trip Database, Australia National Health and Medical Research Council, American College of Physicians, American Medical Association, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Institute of Medicine, National Guidelines Clearinghouse, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Royal College of Physicians, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, and World Health Organization as well as exploring the bibliography of relevant studies and reviews on the topic.

One reviewer (Monelli F) screened the search results based on title/abstract, and then two reviewers(Monelli F and Besutti G) independently examined eligibility based on the full text of the relevant articles.When unclear, inclusion was decided by group consensus with the other authors involved (Monelli F,Besutti G, and Giorgi Rossi P).

Recommendations extraction and synthesis and guideline quality appraisal

One reviewer (Monelli F) extracted the following recommendations of each guideline: the definition of NAFLD and alcohol intake thresholds for defining a non-alcoholic etiology, criteria for eligibility for screening of at-risk population groups, screening modality for at-risk groups, procedures for NAFLD assessment and staging (including diagnosis of NASH and fibrosis), assessment tools and criteria of secondary liver disease, the definition of advanced NAFLD, the role of imaging and of liver biopsy, and research priorities. A cross-check of the extracted data for accuracy was conducted by another reviewer(Besutti G). Every guideline was evaluated using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation(AGREE) II Instrument[14], a tool designed to appraise the methodological rigor, transparency, and applicability of clinical guidelines. The tool provides a rate in percentage for each of six domains, a comprehensive evaluation of the appraised guideline (from 1 to 7) and a final judgment on recommendations for clinical use. Two authors (Monelli F and Besutti G) applied the tool, when scores differed between the two reviewers, a final score was defined by consensus. Guidelines reporting recommendations for adult population and achieving an overall score ≥ 6 using the AGREE II tool were included in a synthesis of extracted recommendations. A synopsis of the extracted topics is reported.

RESULTS

Included guidelines and quality appraisal

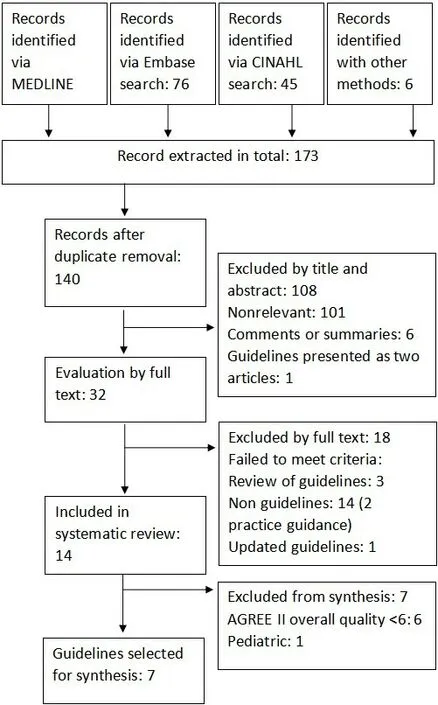

Of the 140 extracted records after duplicate removal, 107 were excluded by title and abstract screening and 18 by full text reading; 14 guidelines were included in this systematic review [Figure 1]. One of the selected guidelines, the US multi-societal guidelines, USA 2012[2], was further integrated with some additional recommendations published in a practice guidance in 2018[15]. This guidance was excluded by the formal selection but was used to integrate USA 2012; thus, in the following synthesis, we refer to the combination of both as USA 2012/2018. Among the 14 included guidelines, 5 were produced in Europe[5,16-19], 5 in Asia and Oceania[20-24], 2 in USA[2,25], including the only 1 specifically developed for the pediatric population[25], 1 in South America[26], and 1 from a supranational institution[27].

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of guidelines search.

Figure 2. Appraisal of included guidelines using AGREE II tool. Domain boxes are colored depending on the score they received, and they are expressed in percentage: red 0% - 35%; yellow 36% - 54%; blue 55% - 74%; light green 75% - 90%; and dark green 91% - 100%.Overall grading is expressed in points from 1 (lowest) to 7 (highest).

The results of the consensus appraisal according to the AGREE II Instrument are presented in Figure 2. The domains with lower scores on average were the rigor of development and stakeholder involvement. The rigor of development domain contains seven subfields which are related to the methods adopted in the production of the guideline. Many of the guidelines analyzed did not use any clear systematic method to search and select the evidence, did not provide a direct connection between scientific works and recommendations, did not describe the strengths and limitations of the body of evidence, and did not provide a procedure or a timeline for guideline updating. For example, WORLD-WGO guideline[27]has low scores in every of those cited domains, while being an excellent guideline in terms of clinical applicability.As concerns the stakeholder involvement domain, many guidelines failed to present how and if the views and preferences of the target population have been evaluated, while most of the guidelines included in the final analysis excelled in taking into consideration the point of view of involved healthcare professionals.Among every analyzed guideline, only UK[16]has a specific section and demonstrates that the patient's point of view was considered in its production.

Among the included guidelines, two reached a score of 7[2,15,16]and six reached a score of 6[5,19-22,25,27]; they were selected as recommended for clinical use by the authors who performed the appraisal, one of these intended for use in pediatric population only.

Publication year ranged from 2010 to 2019, almost the entire range of our search, with 6 documents released before 2015. Methodological quality of the guidelines was not associated with publication year.

Recommendation synthesis

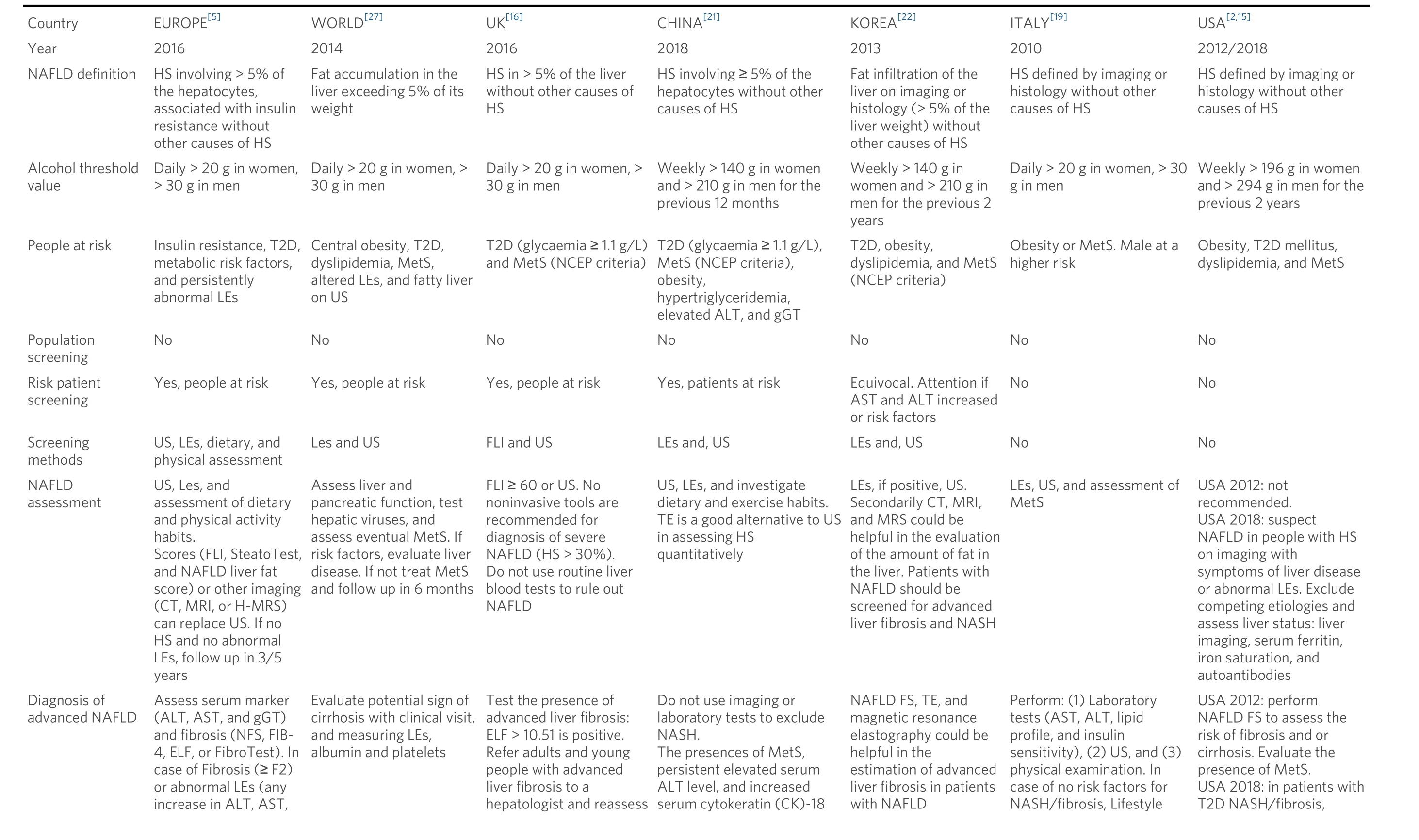

Table 1 presents a summary of the recommendations reported by the guidelines on the adult population and selected as recommended for clinical use according to the quality appraisal. Here, we focus on critical points with higher impact on patient management and safety as well as on the workload for health systems.

Who should be screened for NAFLD

None of the included guidelines recommends a screening for NAFLD in the general population, although most of them recommend a screening or case-finding approach among high-risk patients, mostly defined as patients with metabolic risk factors, including T2D, obesity and metabolic syndrome (MetS)[2,5,16-19,21-24,26,27].

US guidelines (USA 2012/2018)[2,15]still do not recommend such screening because of uncertainties surrounding diagnostic tests and treatment options, although in the last update (USA 2018)[15], the use of clinical decision aids such as fibrosis scores or transient elastography is suggested to find T2D patients at higher risk of fibrosis. Analyzing included guidelines and respective references, the cause of the discrepancy on strategies of high-risk patient screening may be caused by a lack of large studies on the topic. As to the identification of patients at risk of NAFLD, all guidelines require the exclusion of patients with secondary causes of liver steatosis, including steatogenic drugs, and above all, excessive alcohol consumption. In this regard, alcohol thresholds are similar in most guidelines but not identical. In fact, USA 2012/2018[2,15]uses alcohol units instead of grams, resulting in higher thresholds (> 196 g in women and > 294 g in men weekly)as opposed to other guidelines (> 20 g in women and > 30 g in men daily or > 140 g in women and > 210 g in men weekly).

Table 1. Synthesis of recommendations from guidelines on diagnosis and management of NAFLD and NASH/fibrosis in adult population, including guidelines recommended for clinical use after quality appraisal.

ALT: Alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; gGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; US: ultrasound; FLI: fatty Liver Index; LEs: liver Enzymes; NFS: NAFLD fibrosis score; MetS: metabolic Syndrome;T2D: type 2 diabetes; LB: liver biopsy; HS: hepatic steatosis; TE: transient elastography; VCTE: vibration-controlled transient elastography; ELF: enhanced liver fibrosis score.

Which noninvasive tests should be used

Ultrasonography is the preferred first-line diagnostic procedure to screen for NAFLD, while steatosis biomarkers, including fatty liver index (FLI)[28], are considered acceptable alternatives. Liver enzymes are used to guide the identification of patients at higher risk of advanced disease (NASH, fibrosis), even if in some patient categories, especially T2D, advanced disease cannot be ruled out in the presence of normal plasma levels of liver enzymes (EUROPE 2016)[5]. Fibrosis scores [e.g., NFS[29], FIB-4, ELF (enhanced liver fibrosis) score], vibration-controlled transient elastography, or magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) are acceptable noninvasive procedures to identify patients with a low risk of advanced fibrosis (> F2 = portal fibrosis with few septa). If > F2 cannot be excluded, patients should be referred to a hepatologist, who may decide to perform liver biopsy based on the patient’s baseline risk and general clinical conditions, and the opportunity for therapies, frequently within clinical trials in selected settings (EUROPE 2016)[5], (USA 2012/2018)[2,15].

When to perform liver biopsy

The hepatologist should consider liver biopsy in NAFLD patients with high risk of advanced disease (NASH or advanced fibrosis). Hence, the presence of metabolic syndrome, abnormal liver function tests, fibrosis biomarkers, and/or liver stiffness measurements can be used to target patients for liver biopsy. In a recent Chinese guideline (CHINA 2018)[21], high serum levels of CK-18 fragments (M30 and M65) were also introduced as a possible reason for liver biopsy. Finally, liver biopsy is generally considered when other concurrent chronic liver diseases cannot be excluded. All this considered, the decision to perform a liver biopsy is ultimately made by the hepatologist, without common and specific referral criteria, since the definition of high-risk NAFLD patient may be variously interpreted.

Moreover, some of the included guidelines[16,19,21,22]also focus on research priorities related to these points,underlying the necessity to develop noninvasive tests and biomarkers to diagnose NASH and fibrosis, or to assess disease progression, in order to replace liver biopsy or limit its use to a restrict number of patients.

DISCUSSION

Fourteen guidelines have been released on the assessment of NAFLD in recent years and were included in this systematic review. Of the 14, eight obtained a high score on the AGREE II Instrument and are consequently recommended for clinical use, one in the pediatric setting and the other seven for adult management.

The main limitation of this systematic review is that we only included guidelines that were available in English, including translations into English. As clinical recommendations are usually developed for the local clinical community, making them accessible to those practitioners is often preferred rather than to an international audience. Thus, we cannot rule out that some relevant documents have been excluded.Furthermore, as recommendations on NAFLD may be included in guidelines on wider health problems of internal medicine, we may have missed some important documents containing some information relevant to the scope of our review. Nevertheless, the documents retrieved include recent recommendations from a broad range of countries, thereby permitting a meaningful synopsis of the quality and contents of current guidelines. Although a similar review has been published[30], it includes fewer guidelines, probably due to the different search criteria and literature sources (one database only and limited to years 2016 to 2018).Moreover, while the previous revision generally addressed NAFLD assessment and treatment, the present review specifically focuses on NAFLD screening in high-risk patients.

The British and North American guidelines received the highest scores. Notably, among the guidelines with high scores, the most problematic domains in the AGREE II appraisal were Stakeholder Involvement,Rigour of Development, and Applicability. In particular, only the British guidelines involved patients and gave clear evidence of this involvement.

While not all the guidelines agree on the appropriateness of NAFLD screening in high-risk patients,recommendations on NAFLD assessment methods and the role of biopsy as the only definitive diagnostic tool are substantially similar among guidelines, despite the criteria for referring patients to biopsy not being clearly defined. It is worth noting that the issue of screening, with its impact on health service resources and organization and targeting people who have risk factors but not necessarily any disease, requires the involvement of all stakeholders, including citizens, patients, and policy makers. The weakness of the included guidelines on this point may be justified by the difficulties in identifying any patient organization for this health problem. Nevertheless, any future effort made towards developing recommendations on this topic should start with the awareness of the need to involve citizens and patients, from the scoping of the guidelines to their dissemination.

Despite being one of the leading causes of chronic liver disease, with an increasing incidence worldwide[31,32], NAFLD is still frequently overlooked, even as a cause of hepatocellular carcinoma. In Europe, the presence of NAFLD as a cause of liver disease has been shown to double the risk of not receiving appropriate surveillance[33]. This dictates the need for a more systematic approach to NAFLD in order to prevent the transition to advanced stages.

While the definition of NAFLD based on the presence of hepatic steatosis and the exclusion of other causes of fatty liver are identical across guidelines, there are slight differences in terms of the secondary causes of steatosis. In particular, the definition of excessive alcohol consumption is slightly different in terms of time span and volumes. Currently, no guideline suggests a screening of the whole population for the diagnosis of NAFLD, although increasing emphasis is being placed on the early identification of NAFLD in patients with risk factors. As for which risk factors should be taken into consideration, it is generally agreed that T2D and MetS are red flags for NAFLD, though only one guideline (WGO 2014)[27]includes elevated liver enzymes as a factor to select patients to screen. Every guideline selected and included in the synthesis agrees on the adoption of noninvasive methods to diagnose NAFLD in patients at risk, the main one being ultrasound.Nevertheless, one guideline (UK 2016)[16]underlines that sonography can reliably detect steatosis when its histological grade is over 30%, a threshold well over the 5% consensually indicated by every guideline for the diagnosis of NAFLD.

Other methods, such as different elastography techniques (including TE, MRE, and US-based methods),serum markers, and clinical scores, have been proposed to identify patients at higher risk of advanced NAFLD; the choice depends on the patient’s characteristics and the hospital setting to which he/she is referred.

Currently, liver biopsy is still considered the only diagnostic tool that can consistently assess both NAFLD and NASH/fibrosis, especially due to the inability of imaging techniques to accurately diagnose NASH[34].Nevertheless, the adoption of liver biopsy in all patients at high risk of advanced NAFLD to confirm the diagnosis would refer a large number of patients to this invasive test, given the high and increasing prevalence of this disease. Thus, the opportunity of such a strategy for assessing the disease is debated,mainly because of doubts concerning the cost-benefit ratio (UK 2016)[16]and the medical risks stemming from its invasive nature (EUROPE 2016)[5]. Another role of liver biopsy is its ability to detect other underlying hepatic diseases that can be the cause of hepatic steatosis or mimic it. Because of this, USA 2012/2018[2,15]specifically suggests performing liver biopsy on NAFLD patients whenever a coexisting liver disease cannot be excluded. Given these premises, it is not surprising that criteria for referring are unclear in the reviewed guidelines, essentially conferring the individual hepatologist with great discretion.

The limitations of liver biopsy and the lack of clarity of its referral criteria result in the need to focus research efforts on the development of noninvasive tests able to correctly assess advanced NAFLD in order to limit or avoid the use of liver biopsy in clinical practice[16,19,21,22]. In regard to this, some recent studies have demonstrated a reduction in referral rates to secondary care when a combination of noninvasive serum or imaging biomarkers of advanced disease is used[35-38]. Since some of the included guidelines are somewhat outdated[19,22,27], it is possible that upcoming guideline revisions will also focus on a better definition of the use of combined noninvasive biomarkers in clinical practice.

In conclusion, several high-quality guidelines exist for NAFLD assessment. The main area of discrepancy between recommendations from different guidelines is whether screening high-risk patients is opportune and if so, what are the best strategies to do so. A screening limited to patients with metabolic risk factors is mostly recommended, preferably through liver US to confirm steatosis and by means of liver function tests,fibrosis scores, and elastographic techniques to identify patients at risk of advanced disease, who should be considered for liver biopsy.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Major contributors in writing the manuscript: Monelli F, Besutti G, Rossi PG

Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and data analysis and interpretation:Monelli F, Besutti G, Rossi PG, Venturelli F, Riva N, Schianchi S

Data acquisition as well as administrative, technical, and material support: Bonilauri L, Manicardi E,Manicardi V, Bonelli E

Bibliographic search: Bassi MC

Responsible for the conceptualization of the study and its supervision: Besutti G, Rossi PG, Massari M,Ligabue G, Pattacini P

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2021.

- Hepatoma Research的其它文章

- Laparoscopic isolated caudate lobectomy for HCC

- Coffee and hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms

- Mechanisms of protective effects of astaxanthin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Prospects for a better diagnosis and prognosis of NAFLD: a pathoIogist's view

- The evolution of minimally invasive surgery in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma

- The narrow ridge from liver damage to hepatocarcinogenesis