Mechanisms of protective effects of astaxanthin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Ling-Jia Gao, Yu-Qin Zhu, Liang Xu

School of Laboratory Medicine and Life Sciences, Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou 325035, Zhejiang, China.

Abstract Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a major contributor to chronic liver disease worldwide, and 10%-20% of nonalcoholic fatty liver progresses to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Astaxanthin is a kind of natural carotenoid, mainly derived from microorganisms and marine organisms. Due to its special chemical structure,astaxanthin has strong antioxidant activity and has become one of the hotspots of marine natural product research.Considering the unique chemical properties of astaxanthin and the complex pathogenic mechanism of NASH,astaxanthin is regarded as a significant drug for the prevention and treatment of NASH. Thus, this review comprehensively describes the mechanisms and the utility of astaxanthin in the prevention and treatment of NASH from seven aspects: antioxidative stress, inhibition of inflammation and promotion of M2 macrophage polarization,improvement in mitochondrial oxidative respiration, regulation of lipid metabolism, amelioration of insulin resistance, suppression of fibrosis, and liver tumor formation. Collectively, the goal of this work is to provide a beneficial reference for the application value and development prospect of astaxanthin in NASH.

Keywords: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, astaxanthin, fibrosis, insulin resistance, mitochondrial dysfunction,oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become one of the most prevalent forms of chronic liver disease in most countries, and is frequently associated with obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes[1]. NAFLD is characterized by the accumulation of triglyceride (TG) fats by more than 5% to 10% of the liver weight in the absence of superfluous alcohol consumption. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH),an advanced form of NAFLD, is characterized by hepatocellular steatosis, lobular inflammation, and fibrosis, and may lead to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[2-4]. According to global epidemiological research, the global prevalence of NAFLD is increasing year by year and reached approximately 25% by 2016[5-7]. Studies have shown that NAFLD is rapidly increasing as an indicator for liver transplantation, and its incidence in the United States is currently as high as one-third of the total population[8].

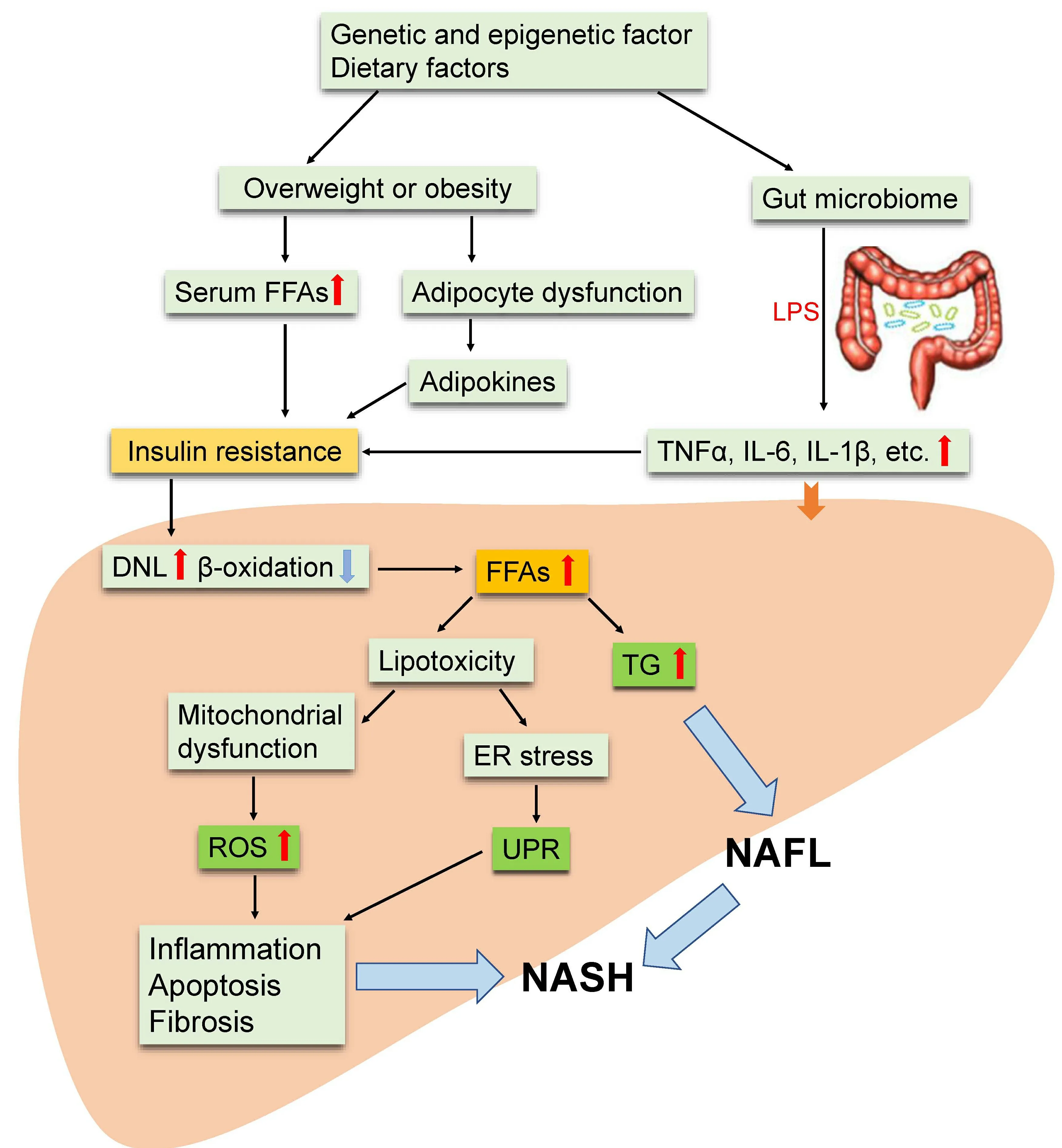

For the pathogenesis of NASH, the widely accepted theory is the “second or multiple hits” hypothesis[9,10], as show as Figure 1. Although insulin resistance, enhanced oxidative stress followed by lipid peroxidation, and rising proinflammatory cytokine release are believed to be the major causes of progression to NASH[11,12], the concrete mechanisms remains obscure. Currently, NAFLD is considered to be an integral part of metabolic syndrome with insulin resistance as the central risk factor. Metabolic syndrome is often characterized by oxidative stress, a disturbance in the balance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defenses[13].

Currently, several pharmacological agents, such as metformin, thiazolidinediones, and vitamin E have been tested as treatments for NASH in clinical trials[14-16]. However, these agents are generally insufficient to ameliorate liver inflammation and fibrosis, and have raised safety concerns. Therefore, a potential therapy with minimal adverse effects is eagerly awaiting. It has recently become clear that the effects of astaxanthin go beyond its antioxidant properties. Astaxanthin is a xanthophyll carotenoid found in marine organisms,including salmon, shrimp, crustaceans, and algae such as Haematococcus pluvialis[17,18]. Accumulating evidence suggests that astaxanthin could prevent or even reverse NASH by improving oxidative stress,inflammation, lipid metabolism, insulin resistance and fibrosis.

The objective of this review is to summarize the bio-functions of astaxanthin in the prevention of NASH.

SOURCE, SYNTHETIC AND BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY OF ASTAXANTHIN

Astaxanthin is a secondary carotenoid with a chemical structure of 3,3’-dihydroxy-4,4’-diketo-β, β’-carotene,which is known for its strong antioxidant activity. It is widely found in nature, such as leaves, flowers, fruits,feathers of flamingos, most fishes, members of the frog family, crustaceans, and the unicellular alga,Haematococcus pluvialis, which is the most ideal source of natural astaxanthin[17,19]. At present, astaxanthin is mainly obtained by the biological extraction of aquatic products and by artificial synthesis from carotene as the raw material. Because synthetic astaxanthin is expensive and less natural than natural astaxanthin in terms of chemical safety and biofunctionality, currently astaxanthin is almost always obtained by biological extraction for its use as a dietary supplement.

At present, astaxanthin is widely used in the food industry as a dietary supplement in a growing number of countries. In 1987, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved astaxanthin as a feed additive for animal and fish feed; in 1999, the FDA authorized it as a dietary supplement for humans[20]. Astaxanthin is lipophilic and hydrophilic, it is absorbed by intestinal epithelial cells in the small intestine and then esterified. It is passively diffused and combined with fat molecules. The unesterified part is combined with chylomicrons and then passed through the lymphatic system for transport into the liver. Spiller and Dewell[21]used a randomized, controlled, double-blind approach to assess the safety of oral administration of astaxanthin (6 mg/d) in healthy individuals. There was no significant difference in blood pressure and various biochemical parameters at 4 and 8 weeks. Humans cannot synthesize astaxanthin, and the ingested astaxanthin cannot be converted to vitamin A; excessive intake of astaxanthin will thus not cause hypervitaminosis A[22,23]. Astaxanthin has physiological functions such as inhibiting tumorigenesis,protecting the nervous system, preventing diabetes and cardiovascular diseases[17,24-27], and it is widely used in various industries such as food, cosmetics, health care products, and aquaculture. Considering the biological characteristics of astaxanthin and the complex pathogenesis of NASH, it remains unknown whether astaxanthin can be used to treat NASH; the underlying mechanism of action also remains obscured.

Figure 1. Multiple-hit hypothesis of the progression of NAFLD/NASH. Dietary habits, environmental, and genetic factors cause overweight or obesity and change the intestinal microbiome. This results in increased serum FFA and inflammatory factor (adipo-, cytoand/or chemokines) levels and eventually leads to insulin resistance. Furthermore, insulin resistance leads to an increase in DNL in the liver and increases the synthesis and accumulation of TG and toxic levels of fatty acids. Fat accumulation in the liver in the form of TG leads to liver steatosis (NAFL). Free cholesterol and other lipid metabolites cause mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent oxidative stress, and ROS release and ER stress further activates UPR; which collectively lead to hepatic inflammation and fibrosis (NASH).NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; FFAs: free fatty acids; DNL: de novo lipogenesis; LPS:lipopolysaccharide; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor alpha: IL-6: interleukin-6; TG: triglycerides; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; UPR: unfolded protein response; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

THE MECHANISM OF ASTAXANTHIN IN THE PREVENTION OF NASH

Anti-oxidative stress effect

As stated above, oxidative stress is one of the various factors that contribute to the “multiple hits” in the pathogenesis of NASH and is the main contributor of liver injury and disease progression in NAFLD.Indeed, several oxidative stress biomarkers that have been determined in clinical models of NAFLD include nitric oxide (NO), lipid peroxidation products [lipid peroxides, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances(TBARS), Hydroperoxides, 8-isoprostane and 4-Hydroxynonenal], protein oxidation products (protein carbonyl, nitrotyrosine), DNA oxidation product (8-OH-dG), and CYP2E1[28,29]. Additionally, two clinical studies have found that increases in oxidative stressin vivo,measured by urinary 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α(8-iso-PGF2α), which is derived from the non-enzymatic oxidation of arachidonic acid and serum levels of soluble NOX2-derived peptide (sNOX2-dp), is an indicator of NOX2 activation, a NADPH oxidase isoform involved in ROS generation[30,31].

Oxidative stress damage is due to the imbalance of oxidation and anti-oxidation processes in the body that cause tissue injury induced by excessive production of free radicals, ROS and reactive nitrogen species(RNS). Excessive ROS can react with proteins, lipids and DNA through a chain reaction, thereby destroying homeostasis and causing tissue damage[32,33]. However, studies have shown that ROS can be eliminated from their oxidative activity by antioxidants such as carotenoids. Carotenoids contain polyene chains and longchain conjugated double bonds, which are responsible for antioxidant activities, acting by quenching singlet oxygen to terminate the free radical chain reaction in the organism[34,35]. Astaxanthin, one of the most prominent carotenoids with antioxidant activity, can penetrate the whole cell membrane, reduce membrane permeability, and limit the entry of peroxide promoters such as hydrogen peroxide and tert-butyl hydroperoxide into the cell[36,37]. Thus, oxidative damage to pivotal molecules in cells can be prevented.Astaxanthin scavenges oxygen free radicals and prevents lipid auto-oxidation with a capacity that is 6,000 times greater than that of vitamin C, 800 times that of coenzyme Q10, 550 times that of vitamin E, 200 times that of tea polyphenols, and 10 times that of beta carotene[17,38]; rightfully therefore known as a “super antioxidant”. Jorgensenet al.[39]found that astaxanthin is more effective than beta-carotene and zeaxanthin in preventing excessive oxidation of unsaturated fatty acid methyl esters. This conclusion has also been verified in various biofilm models, including phosphatidylcholine liposomes[40]and rat liver microsomes[37].

Nakagawaet al.[41]reported that supplementation with astaxanthin (6 and 12 mg/d) in 30 healthy subjects decreased erythrocyte phospholipid hydroperoxide (PLOOH) levels and increased astaxanthin levels, 12 weeks after administration. An animal study showed that the concentration of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) increased significantly in the plasma and hepatocytes of rats that were fed Haematococcus pluvialis[42]. In obese and overweight adults, astaxanthin supplementation (5 and 20 mg/d) dramatically reduced the level of biomarkers related to oxidative stress, including malondialdehyde (MDA) and isoprostane, and increased SOD and total antioxidant capacity (TAC). These findings indicate the strong antioxidant capacity of astaxanthinin vivo[43].

Anti-inflammatory effect and enhancement in M2 macrophage polarization

Given the strong link between inflammation and oxidative stress, it is not surprising that astaxanthin has been studied as an agent to attenuate inflammation.In vitro, astaxanthin has been shown to reduce proinflammatory markers in several cell lines, such as rat alveolar macrophages[44], U937 cells[45], RAW 264.7 cells[46], Thp-1 cells[24], proximal renal tubular epithelial cells[47], HUVECs[48], and human lymphocytes[49].

Wanet al.[50]demonstrated that M2 macrophage/Kupffer cells promote apoptosis in M1 macrophage/Kupffer cells and inhibit NAFLD progression. Astaxanthin restrains M1 macrophage/Kupffer cells and increases M2 macrophage/Kupffer cells, reducing liver recruitment of CD4+and CD8+cells and inhibiting inflammatory responses in NAFLD[51]. Inflammatory factors aggravate the progression of NAFLD; however, astaxanthin reduces the levels of interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α in the liver through proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) to alleviate inflammation[52]. When NASH was induced by diet, administration of natural astaxanthin (0.02%, ≈ 20 mg/kg BW) reduced liver inflammation and insulin resistance in C57BL/6J mice[51]. Compared to vitamin E, astaxanthin was more effective in preventing and treating NASH in this animal model[51].

Recently, the gut-liver axis has been shown to mediate the NASH progression[53]. Notably, liver lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is produced by intestinal microbiota, which were known to induce oxidative stress and inflammation. The LPS/toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling is critical for the activation of inflammatory pathways associated with NASH[54]. Lumenget al.[55]found that in primary macrophages and RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by LPS, astaxanthin significantly reduced the levels of NO, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), TNFα, and IL-1β by inhibiting NF-κB activation. Macedoet al.[56]showed that astaxanthin can obviously reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-6, secreted by LPS-induced neutrophils and enhance the phagocytosis and bactericidal ability of neutrophils by inhibiting the production of O2-(superoxide anion radical) and H2O2.

Improvement of mitochondrial respiratory chain

Numerous studies have shown that excessive ROS can cause oxidative damage to mitochondria. In turn,damage to the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I and III releases electrons to produce a large amount of ROS; approximately 90% of ROS in cells are produced from mitochondria. Superfluous ROS cause mitochondrial structural abnormalities and functional deficits, mainly manifested in decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial mutation, uncoupling of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, increased free radical production, and decreased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production.Dysfunctional mitochondria trigger inflammatory cytokine production and often lead to the development of degenerative diseases, aging, metabolic diseases, cardiovascular diseases and so on.

A growing body of studies has also involved astaxanthin in improving cellular mitochondrial oxidative respiratory chains to resist oxidative stress damage, and recent results hypothesize that astaxanthin has a“mitochondrial targeting” effect in cells. Fanet al.[57]verified that astaxanthin significantly attenuated homocysteine-induced cytotoxicity of H9C2 cells by inhibiting mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and blocked homocysteine-induced mitochondrial dysfunction by modulating the expression of the Bcl-2 family. Importantly, astaxanthin also significantly inhibits homocysteine-induced cardiotoxicityin vivoas well as improves angiogenesis. A similar study has shown that astaxanthin has the potential to reverse homocysteine-induced neurotoxicity and apoptosis by inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction and ROSmediated oxidative damage and regulating the MAPK and AKT pathways[58]. After treatment of gastric epithelial cells with astaxanthin, Kimet al.[59]found that Helicobacter pylori-induced increases in ROS,mitochondrial dysfunction, NF-κB activation, and IL-8 expression were alleviated without affecting NADPH oxidase activity, indicating thereby that astaxanthin could prevent oxidative stress-mediated Helicobacter pylori infection that is associated with gastric inflammation Yuet al.[60]also found that astaxanthin can improve heat-induced skeletal muscle oxidative damage. In mouse C2C12 myoblasts exposed to heat stress at 43 ℃, astaxanthin lessened heat-induced ROS production in a concentrationdependent manner (1-20 μM), preventing mitochondrial disruption, depolarization and apoptotic cell death. Astaxanthin increases the protein expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1β (PGC-1α) and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) at 37 ℃, and maintains mitochondrial tubular structure and a normal membrane potential (ΔΨm), i.e., maintainance of mitochondrial integrity and function. Data from Manoet al.[61]showed that astaxanthin inhibits oxidation and nitridation, which leads to apoptosis and lipid peroxidation of cytochrome c peroxidase, although its efficiency varies with membrane pH and lipid composition. It is hypothesized that astaxanthin is endowed with pH-dependent antioxidant/antiapoptotic properties in respiratory mitochondria. Astaxanthin and tocopherol nanoemulsions (NEs) were prepared using sodium caseinate (AS-AT/SC NEs) as a raw material to protect cells from ROS, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial membrane potential through mitochondriamediated apoptosis to prevent cell death, demonstrating therefore that apoptosis induced by AS-AT/SC NEs may be a potential method to destroy cancer cells[62]. Taken together, astaxanthin can ameliorate mitochondrial glutathione (GSH) activity, complex I activity, ATPase activity, mitochondrial membrane potential and fluidity by ROS, and excessively open the membrane permeability transition pore (MPTP)[63].

Although an accurate discussion is lacking on the mechanisms by which mitochondria might assist in the prevention and treatment of NASH, the above studies suggest that mitochondrial function plays an indelible role in NASH.

Lipid metabolism

Jiaet al.[52]administered astaxanthin orally to C57BL/6J mice that were fed a high-fat diet for 8 weeks and found that astaxanthin could improve liver lipid accumulation and decrease liver TG levels. Astaxanthin was found to regulate PPAR levels. Activated PPARα increases liver fatty acid transport, metabolism, and oxidation levels; inhibits liver fat accumulation; induces hepatocyte autophagy; and cleaves lipid droplets through AMP-activated protein kinase/PGC-1α[64-66]. PPARα has become a key target for the treatment of NAFLD - activation of PPARγ regulates lipid synthesis-related gene expression and promotes fatty acid storage, and PPARγ overexpression induces hepatic lipid accumulation[67]. Astaxanthin activates PPARα,inhibits PPARγ expression, and reduces intrahepatic fat synthesis[63]. In addition, astaxanthin inhibits the AKT-mTOR pathway, which also causes autophagy of liver cells and breaks down lipid droplets stored in the liver[52]. Furthermore, astaxanthin reduces liver fatty acid synthesizing enzyme (FASN) mRNA levels and directly inhibitsde novosynthesis of fat[68].

In vitroand clinical studies have shown that the continuous use of astaxanthin for 2 weeks can significantly prolong the oxidation time of low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Astaxanthin can inhibit the production of ox-LDL and the utilization of ox-LDL by the activation of macrophages along with the enhanced expression of PPARα. At the same time, it inhibits the expression of PPARγ and reduces the synthesis of fat in the liver.Augustiet al.[69]found that astaxanthin can significantly reduce oxidative stress damage and program lower blood lipid levels in rabbits with hypercholesterolemia. In patients with hypertriglyceridemia, serum TG levels of patients with long-term oral astaxanthin were significantly lower than those in the control group,while adiponectin and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels were significantly increased[70]. In obese and overweight people, oral astaxanthin lowers apolipoprotein B and LDL cholesterol levels and improves oxidative damage[43]. It has been reported that astaxanthin also reduces platelet aggregation and promote fibrinolytic activity in rats with hyperlipidemia induced by a high-fat diet. These positive effects are related to decreased serum lipid and lipoprotein levels, antioxidant production, and protection of endothelial cells[71].

Amelioration of insulin resistance

Insulin resistance is the major contributor to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and NAFLD. Insulin activates the tyrosine kinase activity of insulin receptor-beta (IRβ) subunits, which phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate, IRS, to activate the insulin metabolism pathway: IRS1-PI3K-AKT (insulin receptor substrate 1,phosphoinositide 3-kinase, serine/threonine kinase). When serine/threonine protein kinases, such as Jun Nterminal kinases (JNK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 (ERK-1), inhibitors of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase (NF-κB) subunit beta (IKK-β), phosphorylate IRβ and IRS1, the IRS1-PI3K-AKT pathway is blocked and its activity decreases, and insulin resistance occurs accordingly[72,73]. The activation of JNK and NF-κB, stimulated by sustained endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress also causes insulin resistance[74].Bhuvaneswariet al.[75,76]established a mouse model of type 2 diabetes induced by a high fructose-fat diet(HFFD) to study the effects of astaxanthin on hepatic insulin signaling and glucose metabolism.Astaxanthin intervention significantly improved insulin sensitivity in the HFFD group. This is because astaxanthin restores the insulin metabolic pathway by decreasing the activity of JNK and ERK-1 to ameliorate insulin resistance in the liver. Niet al.[51]constructed a diet-induced NASH mouse model that consisted of a high-fat, high cholesterol, and cholate diet (CL). In the fasting and fed states, glucose intolerance and hyperinsulinemia that accompanied the CL diet were significantly ameliorated by astaxanthin, and vitamin E treatment also reduced the plasma insulin levels to some extent. This result was related to the fact that astaxanthin-treated mice produced more insulin-stimulated phosphorylated IRβ and AKT than did control mice, while vitamin E had little effect on hepatic insulin signaling.

Anti-fibrosis effect

Hepatic fibrosis is a wound healing response characterized by excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix. Hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation plays a key role in liver fibrosis[77]. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) is the most effective profibrotic cytokine[78]. TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling regulates transcription of key genes in fibrosis, causing liver fibrosis. The imbalance in matrix metalloproteinases(MMPs) and MMP inhibitors (tissue inhibitor of MMPs, TIMPs) accelerates the progression of liver fibrosis, and TGF-β1 regulates the expression of MMPs and TIMPs. Yanget al.[79]confirmed that astaxanthin can reduce the expression of the TGF-β1-induced fibrosis genes α-SMA and Col1A1 and effectively inhibit fibrosis in LX-2 cells. The mechanism is that astaxanthin downregulates Smad3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation induced by TGF-β1. Yanget al.[79]also observed that when activated primary HSCs were coincubated with astaxanthin, α-SMA mRNA and protein levels were significantly downregulated, indicating that astaxanthin can inhibit the early activation of resting HSCs.Shenet al.[80]studied the protective effect of astaxanthin on liver fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride(CCl4) and bile duct ligation. The results showed that astaxanthin effectively improved the pathological damage of liver fibrosis. Astaxanthin reduces the expression of TGF-β1 by downregulating nuclear NF-κB levels, maintains the balance between MMP2 and TIMP1, and inhibits the activation of HSCs and the formation of extracellular matrix (ECM). Hernandez-Geaet al.[81]reported that autophagic degradation of lipid droplets in HSCs provides energy for HSC activation, thereby aggravating the process of liver fibrosis.Astaxanthin alleviates HSC autophagy levels, reduces nutrient supply, and inhibits HSC activation. In addition, histone acetylation, as an epigenetic model, is involved in the activation of HSCs and the process of liver fibrosis[82]. Some studies have found that astaxanthin significantly suppresses the activation of HSCs by decreasing the expression of histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9); HDAC3 and HDAC4 may also be involved in this process[74].

Antitumor formation

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a malignant tumor with extremely high morbidity and mortality.Multiple signaling pathways, such as NF-κB p65, Wnt/beta-catenin, JAK/STAT, Hedgehog, Ras/MAPK and so on, are closely related to the development of liver cancer[83,84]. In the aflatoxin (AFB1)-induced liver cancer model, astaxanthin markedly reduced the number and size of liver cancer lesions. In-depth studies have found that astaxanthin significantly inhibits AFB1-induced single-strand DNA breaks and AFB1 binding to liver DNA and plasma albumin[85]. Tripathiet al.[86]found that astaxanthin inhibits cyclophosphamide-induced liver tumors in the early stage in rats. The Nrf2-ARE pathway is an endogenous antioxidant stress pathway that regulates the expression of SOD and DNA repair enzymes (e.g., OGG1,XRCC1, XPD, and XPG), which play an important role in tumorigenesis and progression[87,88]. Astaxanthin can inhibit the occurrence and development of liver cancer, which in turn, may be related to the activation of Nrf2-ARE pathway.

Songet al.[89]confirmed that astaxanthin induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in the mouse liver cancer cell line CBRH-7919 by inhibiting the JAK/STAT3 pathway. In addition, astaxanthin inhibits liver tumorigenesis and may be involved in the regulation of NM23, which encodes a nucleoside diphosphate kinase. The upregulated expression of this protein is beneficial to the correct assembly of the cytoskeleton and the transmission of T protein signaling. Liet al.[90]confirmed that astaxanthin can prevent the proliferation of human hepatoma cells LM3 and SMMC-7721 and induce their apoptosis. The possible mechanism is that astaxanthin inhibits the NF-κB and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways and regulates downstream the expression of the antiapoptotic protein, Bcl-2, and apoptosis-related gene, Bax; thereby promoting apoptosis of tumor cells. At the same time, astaxanthin decreases the phosphorylation of glycogen synthetase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β) and inhibits tumor cell infiltration. Consistent with these findings, Shaoet al.[91]showed that astaxanthin can inhibit the proliferation of mouse hepatoma cell line H22 and arrest cells in the mitotic G2 phase.

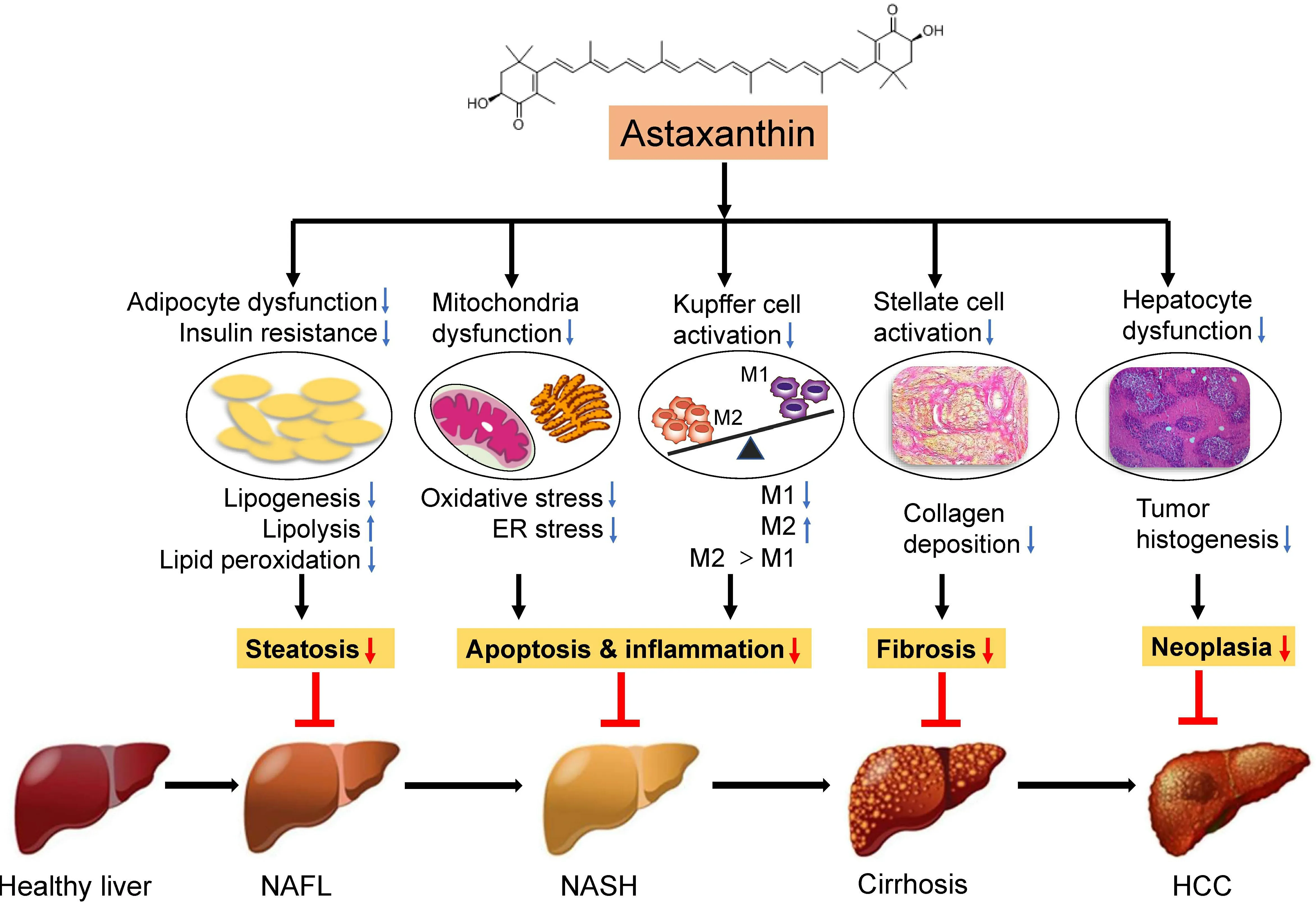

Figure 2. Mechanisms of the effects of astaxanthin on NASH. The strong antioxidant effect of astaxanthin can significantly inhibit oxidative stress, thereby reducing mitochondrial damage and endoplasmic reticulum stress, leading to a shift to M2 macrophage polarization and ultimately reversing liver steatosis, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Moreover, astaxanthin can reduce the activation of hepatic stellate cells to ameliorate hepatic fibrosis as a result of M1/M2 macrophage transformation. In addition,astaxanthin can inhibit the generation of hepatocyte tumors. Thus, astaxanthin prevents the development of NAFLD by inhibiting lipid accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis in the liver. NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; KC:Kupffer cell; M1: proinflammatory macrophages; M2: anti-inflammatory macrophages; HSC: hepatic stellate cells; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

The increase inde novofat synthesis is a common feature of many malignant tumors. FASN is expressed in a variety of malignant tumors, including liver cancer[92,93], and astaxanthin downregulates liver FASN mRNA levels to restrain liver tumorigenesis[94]. In addition, adipocytokines, another key regulator of the fat synthesis pathway, play an important role in repressing the proliferation of human liver tumor cells and inducing apoptosis. Astaxanthin observably inhibits liver tumorigenesis in obese mice by increasing serum adipocytokine levels[95].

CONCLUSION

Astaxanthin has been recognized as a new food resource and is expected to have good application prospects in health food and dietary supplements. The prevalence of NASH continues to persist globally, and its complex and diverse pathogenesis makes it difficult to diagnose and treat. Currently, there are no FDAapproved standard drug regimens in the guidelines for management of NASH. At present, great progress has been made in researching the antioxidant activity of astaxanthin. A large number of studies have demonstrated that astaxanthin can prevent or treat NASH through various mechanisms [Figure 2]. Most studies on the influence of astaxanthin on NASH remain at the cellular and animal experiment level.However, the presented research in this work on the prevention and treatment of NASH by astaxanthin indicates that there is broad potential and hope for the application of astaxanthin in NASH. As a futuristic goal, we still need large-scale clinical trials to verify the actual effects of astaxanthin on the human body and provide a theoretical basis to continually explore the beneficial effects of astaxanthin antioxidant activity on the human body.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Contributed to the drafting and writing of the manuscript: Gao LJ, Zhu YQ, Xu L

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by Xinmiao Talents Program of Zhejiang Province granted to L.G (2019R413070)and Wenzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau granted to L.X. (Y20190049).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2021.

- Hepatoma Research的其它文章

- Laparoscopic isolated caudate lobectomy for HCC

- Coffee and hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms

- Prospects for a better diagnosis and prognosis of NAFLD: a pathoIogist's view

- Systematic review of existing guidelines for NAFLD assessment

- The evolution of minimally invasive surgery in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma

- The narrow ridge from liver damage to hepatocarcinogenesis