Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer: A multicenter retrospective study

Takuya Satomi, Sejji Kawano, Tomoki Inaba, Masahiro Nakagawa, Hirokazu Mouri, Masao Yoshioka, Shoichi Tanaka, Tatsuya Toyokawa, Sayo Kobayashi, Takehiro Tanaka, Hiromitsu Kanzaki, Masaya Iwamuro, Yoshiro Kawahara, Hiroyuki Okada

Abstract

Key Words: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; Gastric tube; Gastric cancer; Esophagectomy; Multicenter study; Retrospective study

INTRODUCTION

Recently, the survival of patients with esophageal cancer after esophagectomy has improved[1-5]. However, the risk of a subsequent occurrence of primary cancer is high in these patients. The most frequent cancer that overlaps with esophageal cancer is head and neck cancer, while the second most common is gastric cancer, including gastric tube cancer (GTC)[6-9]. Therefore, the improved prognosis of esophageal cancer patients has led to an increase in the occurrence of GTC in the reconstructed gastric tube.

For the treatment of GTC after esophagectomy, total gastric tube resection (TGTR) or partial gastric tube resection (PGTR) has been proposed. However, surgical resection for GTC, being a secondary operation following esophagectomy, may lead to high mortality and morbidity[10,11]. On the other hand, in recent years, endoscopic therapy for early gastric cancer (EGC) has developed and become widespread[12]. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) enables the treatment of large lesions with a higher rate of en bloc resection that cannot be achieved by using conventional endoscopic mucosal resection. In addition, ESD is less invasive than surgery. For this reason, ESD has become widely used as a standard treatment for EGC, and ESD is often performed for GTC.

However, ESD for GTC after esophagectomy is a technically difficult procedure compared with that for an unresected stomach because of the limited working space, unusual fluid-pooling area, food residue, bile reflux, fibrosis, and staples under the suture line[13]. Therefore, a high degree of skill is required for ESD of GTC. There are few reports about ESD for GTC after esophagectomy, and most are case reports and case series of a small number of patients[13-17]. A study by Nonaka et al[18]reported the effectiveness and safety of ESD for GTC in a high-volume national center, which had largest number of cases but was nonetheless a single-center study. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ESD for GTC after esophagectomy in a multicenter context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively investigated patients with GTC in the reconstructed gastric tube after esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who had undergone ESD between January 2005 and December 2019 at 8 institutions participating in the Okayama Gut Study group (O-GUTS). All of the participating institutions in O-GUTS, except Okayama University Hospital (OUH), were considered core hospitals in each area. During the study period, 48 GTC lesions in 38 consecutive patients were treated. The clinical indications of ESD for EGC were based on the Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines[19]. These indications were similarly applied for GTC after esophagectomy with gastric tube reconstruction.

Study measurements were as follows: patient characteristics, endoscopic findings, treatment results, adverse events, histopathological results, and clinical courses. In addition, we defined OUH as a high-volume center and compared the patients’ background and clinical outcomes between OUH and other facilities.

The institutional review board of each hospital approved this study, and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Endoscopic procedures

All endoscopic procedures were performed by experts in ESD who had experience with more than 500 clinical cases. There were no restrictions on the scopes and devices used by each endoscopist for ESD. The scopes used were GIF-Q260J or GIF-H260 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and the devices were an insulation-tipped diathermic knife (IT Knife), IT Knife 2, IT Knife nano, or Dual Knife J (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Other devices, such as an argon plasma coagulation probe (ERBE, Tubingen, Germany) for marking dots or a needle knife (ZEON MEDICAL, Tokyo, Japan) for the initial incision, were occasionally used.

First, marking dots for the incision lines were placed around the lesion. Next, fructose-added glycerol (Glyceol; TAIYO Pharma CO, Tokyo, Japan) with a minute amount of indigo carmine dye was injected into the submucosal layer. In some cases, 0.4% sodium hyaluronate (MucoUp; Boston Scientific, Tokyo, Japan) was used. After submucosal injection, a precut was made with the Dual Knife J or needle knife, followed by a circumferential mucosal incision around the lesion using the dots as a landmark and submucosal dissection with the IT Knife, IT Knife 2, IT Knife nano, or Dual Knife J. The resected specimens were evaluated pathologically.

Histopathological assessment of curability

ESD specimens were evaluated in 2-mm slices according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma with curability assessments divided into curative and noncurative resection based on the Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines[20]. R0 resection indicated that the lesion was resected en bloc with both the horizontal and vertical margins tumor-free histopathologically, but did not include findings regarding lymphovascular infiltration, the type of adenocarcinoma, or an assessment of the depth of invasion for curability. A curative resection was divided into eCura A and eCura B. A non-curative resection was defined as not meeting the criteria of curative resection and was further separated into 2 groups, eCura C-1 and eCura C-2, based on histopathological results per the Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines[19].

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical variables are expressed as median (range) and n (%), respectively. Overall survival was calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in the clinical outcomes of ESD for GTC between institutions were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. The risk factors for long procedure time were evaluated using logistic regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical analysis software JMP Pro, version 15 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics and endoscopic findings

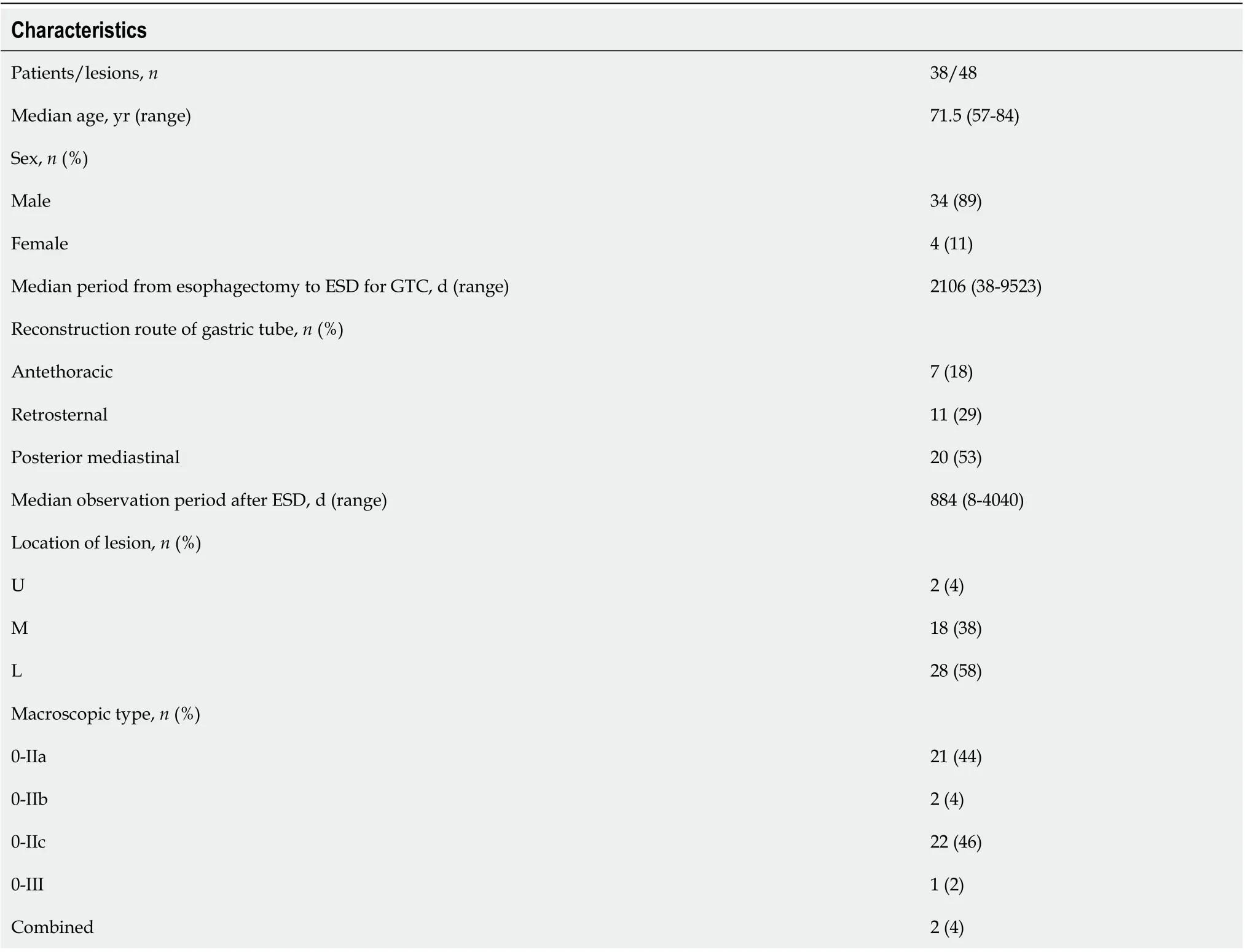

A total of 38 consecutive patients with 48 GTC lesions were treated with ESD between January 2005 and December 2019 (Table 1). The median age of these patients was 71.5 years (range, 57-84 years), and they included 34 men and 4 women. The median period from esophagectomy to the treatment of GTC was 2106 d (range, 38-9523 d). This included patients who had a diagnosis of EGC before surgery for esophageal cancer and had undergone ESD after esophagectomy (5 patients). The reconstruction routes were antethoracic, retrosternal, and posterior mediastinal in 7, 11, and 20 patients, respectively. The location of the GTC lesion was upper, middle, and low in 2, 18, and 28 patients, respectively. Regarding the macroscopic type, there were 21 lesions of 0-IIa, 22 lesions of 0-IIc, 2 lesions of 0-IIb, 1 lesion of 0-III, and 2 combined lesions. The median observation period after ESD was 884 d (range, 8-4040 d).

Treatment results of ESD and histopathological findings

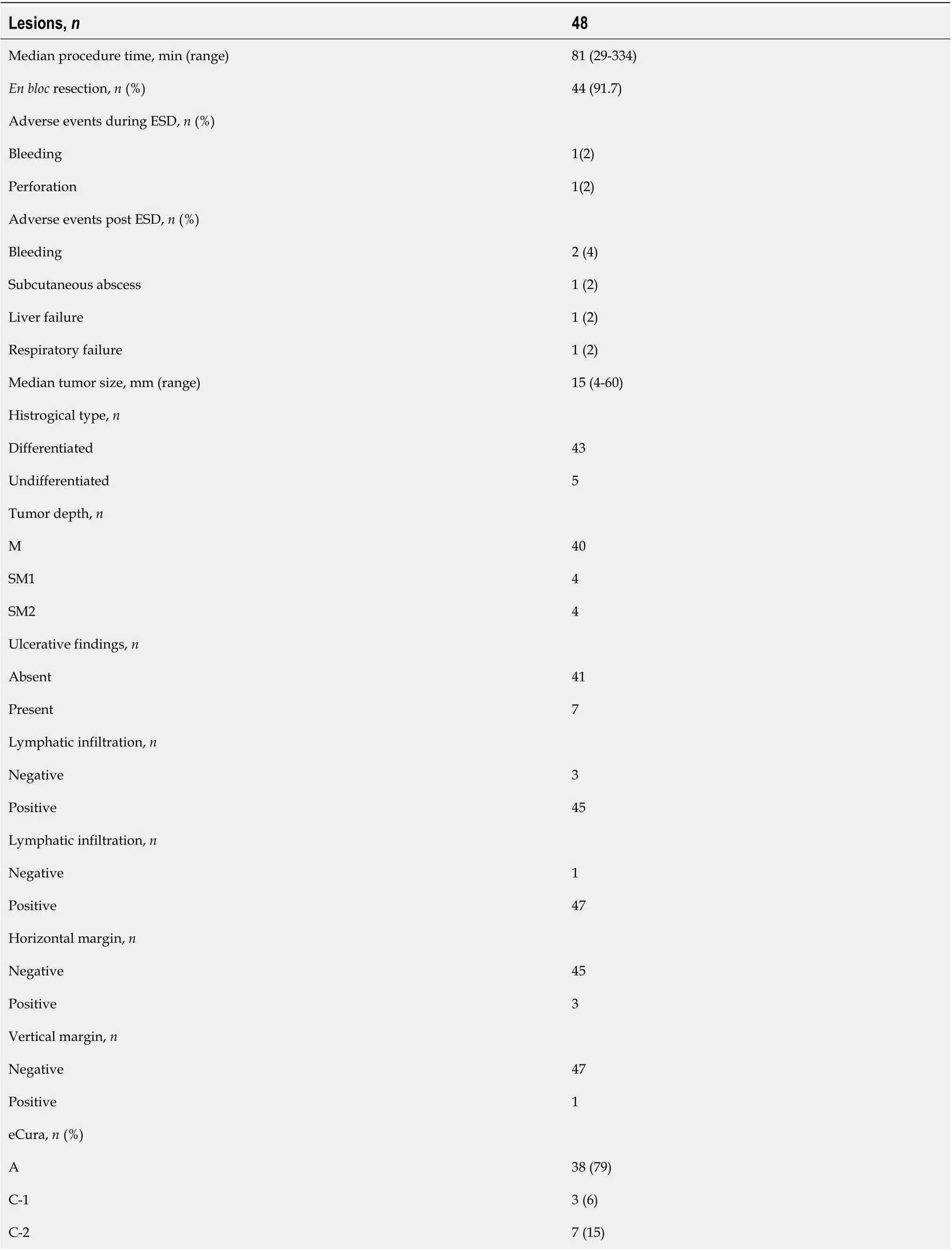

Treatment results of ESD for GTC after esophagectomy and pathological findings are shown in Table 2. The median procedure time was 81 min (range, 29-334 min). En bloc resection was performed in 44 of 48 lesions (91.7%). The median tumor size of the resected specimen was 15 mm (range, 4-60 mm). Among the 48 lesions, 43 were differentiated (90%) and 5 were undifferentiated (10%). Regarding the tumor depth, 40 lesions were intramucosal carcinoma (M, 84%), 4 were submucosal superficial carcinoma (SM1, 8%), and 4 were submucosal deep invasive carcinoma (SM2 or deeper, 8%). Ulcerative findings were seen in 6 lesions (13%). Lymphatic infiltration was seen in 3 lesions (6%), and vascular infiltration was seen in 1 lesion (2%). According to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines, 38 lesions (79%) achieved curative resection (eCura A) and 10 lesions (21%) were classified as noncurative resection. The reasons for non-curative resection were as follows: 3 lesions were horizontal margin positive (HM1) or cutting into the lesion (eCura C-1), 2 were undifferentiated and showed SM invasion, 2 showed lymphatic infiltration, 2 showed SM invasion with ulcerative findings, and 1 was undifferentiated and showed SM invasion and lymphatic and vascular infiltration (eCura C-2).

Adverse events

Complications during ESD were seen in 2 cases (4%), with 1 case of perforation, and 1 case of bleeding. Complications after ESD were seen in 5 cases (10%), with 2 cases of bleeding, 1 case of subcutaneous abscess, 1 case of liver failure, and 1 case of respiratory failure (Table 2).

Table 1 Patients’ characteristics and endoscopic findings

It was the same patient who had perforation during ESD and who formed subcutaneous abscess after ESD (Figure 1). In this case, perforation during ESD was sealed immediately with endoclips. Nevertheless, 20 d after ESD, the patient was admitted to the hospital with redness of the skin in the precordial area and excretion of pus from the skin. Computed tomography showed formation of a subcutaneous abscess around the gastric tube of the antethoracic reconstruction route. The patient was treated conservatively with antibiotics and percutaneous drainage and was discharged on the 16thday after the start of re-admission.

Patients’ clinical courses

Of the 38 cases, 2 had local recurrence and 3 had metachronous recurrence. In the 2 cases with local recurrence, 1 received additional surgery and the other received additional ESD. In the 3 cases with metachronous recurrence, 1 received additional surgery and the others received additional ESD. The patients’ overall survival curve is shown in Figure 2. The survival rate at 5 years was 59.5%. During the observation period after ESD, no patient died of GTC. However, 10 patients died of other diseases, including pneumonia, which was the most common and occurred in 4 patients, heart failure and hepatocellular carcinoma in 1 patient each, and other unknown diseases.

Comparison of clinical outcomes

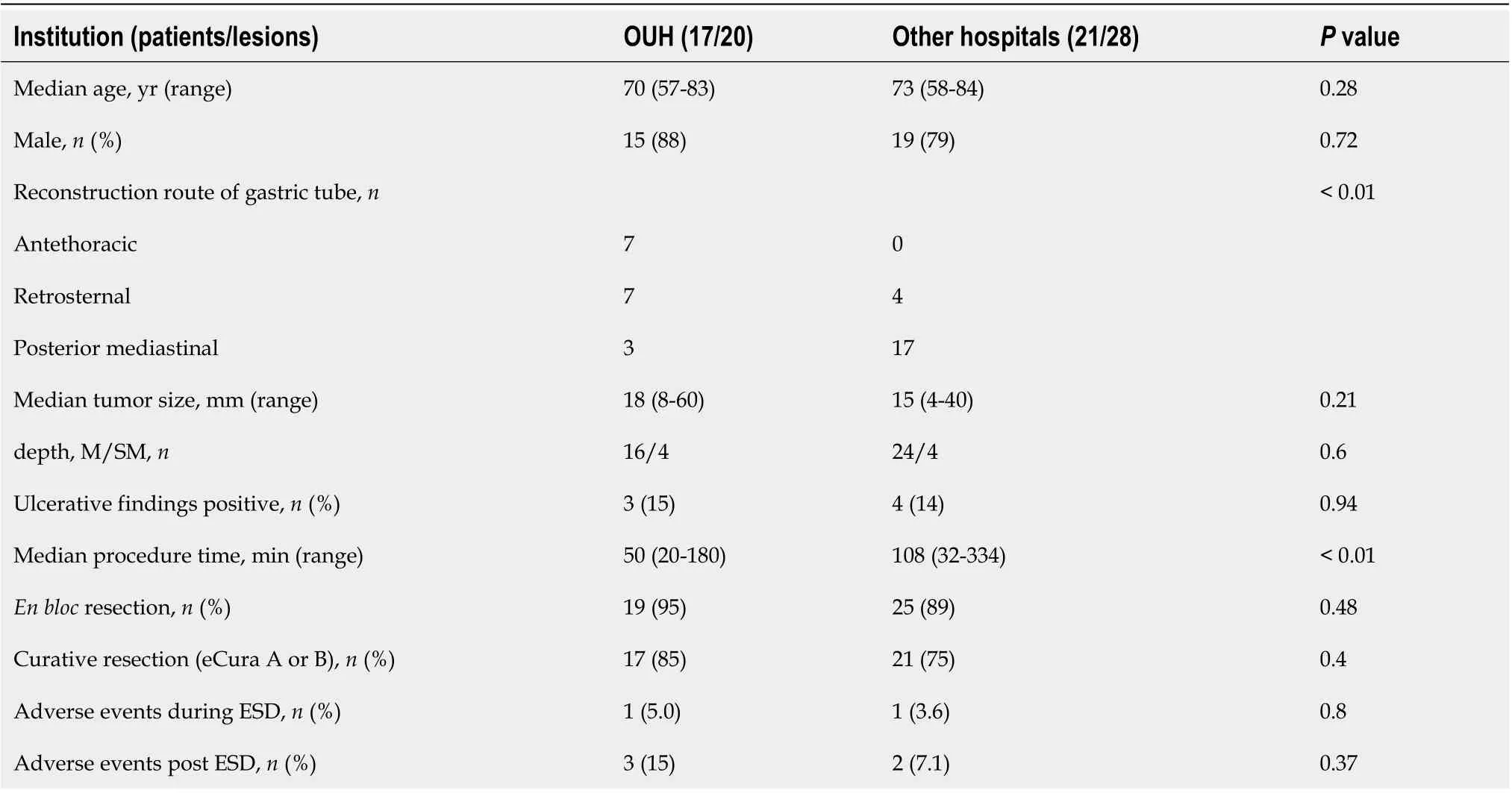

A comparison of the patients’ background and clinical outcomes between OUH and other hospitals is shown in Table 3. In terms of the patients’ backgrounds, the posterior mediastinal route was used as a reconstruction route in more cases at other hospitals. Treatment results were generally similar in both groups; however, procedure time was significantly longer at other hospitals.

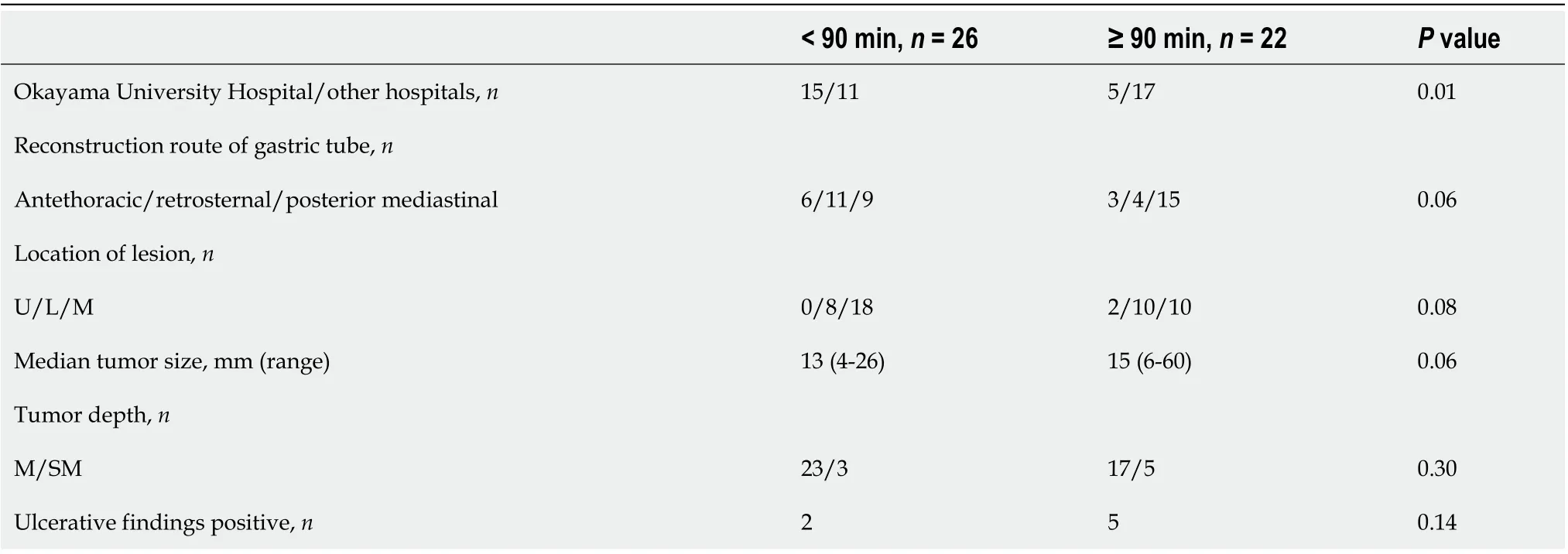

Since there were differences in procedure time between institutions, we dividedpatients into two groups, a short procedure time group (< 90 min) and a long procedure time group (≥ 90 min), and examined the factors affecting the procedure time. In univariate analysis (Table 4), the treatment institution and tumor size showedsignificant differences between the two groups. However, in multivariate analysis (Table 5), tumor size was the only factor associated with a long procedure time.

Table 2 Treatment results of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer and histopathological findings

Table 3 Comparison of clinical outcomes between Okayama University Hospital and other hospitals

Table 4 Comparison of short (< 90 min) and long (≥ 90 min) procedure time groups

DISCUSSION

This study was the first multicenter study on ESD for GTC in the reconstructed gastric tube after esophagectomy, and it included the second largest number of patients. According to a systematic review of GTC after esophagectomy, there are two surgical options for the treatment of GTC: PGTR or TGTR plus lymphadenectomy with colon or jejunal reconstruction[21]. However, surgical treatment for GTC is highly invasive and carries a certain degree of risk. Sugiura et al[10]reported that 5 of 7 cases of TGTR had surgical complications (leakage) and 2 died. In addition, 1 of 3 cases of PTGR had fatal complications. Akita et al[11]reported that 1 of 5 cases of TGTR died of postoperative complications. On the other hand, in previous studies on ESD for GTC,the proportions of R0 resection and curative resection were 87.5%-92% and 65%-85%, respectively, and complications were seen in 12.5%-18% of patients[13-18]. In the present study, the proportions of R0 resection and curative resection were 91.7% and 79%, respectively, and complications were seen in 10%. Overall, the treatment results of ESD for GTC in this study were similar to those of previous studies. In a previous study on gastric ESD of the unresected stomach, the proportions of R0 resection, curative resections, and complications were 92%-94.9%, 80.4%-94.7%, and 5.9%-6.3%, respectively[22,23]. Furthermore, in gastric ESD of the remnant stomach after gastrectomy, the proportions of R0 resection, curative resection, and complications were 84.7%-85%, 70.9%-78%, and 2.8%-21.1%, respectively[24,25]. ESD for GTC was considered a minimally invasive, effective, and relatively safe treatment.

Table 5 Multivariate analysis about risk factors for a long procedure time of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer

There are some points of note in GTC. First, detection of early GTC requires longterm regular endoscopic surveillance after esophagectomy. GTC is often found long after esophagectomy; in some cases, GTC is detected after more than 10 years and the risk of metachronous GTC is high[15-18]. Second, GTC may be difficult to diagnose. The reasons are as follows: Food residue and bile reflux are often seen in the gastric tube, and the lumen of the gastric tube is long and narrow and can constrain endoscopic observation[13]. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to these points during endoscopy for patients with gastric tube reconstruction after esophagectomy. Third, when performing ESD for GTC, it is necessary to pay attention to complications specific to GTC. For example, in our study, a subcutaneous abscess formed after treatment in a case with perforation during ESD for GTC in the antethoracic reconstruction route. This case was cured by conservative treatment with antibiotics and percutaneous drainage. Moreover, Miyagi et al[26]reported that post-treatment precordial skin burns occurred in 5 of 8 patients with GTC in the antethoracic reconstruction route. In this report, all burns were diagnosed as first-degree burns based on the clinical classification of burn depth, developed on postoperative day 1-2, and took 4-7 d to heal.

In this study, since approximately half of the patients were treated at OUH, we defined it as a high-volume center and compared clinical outcomes with those of other institutions. As a result, there were no significant differences in the clinical outcomes of ESD between institutions. In addition, lesion size was the only factor related to long procedure time in multivariate analysis. We believe these results were attributable to the fact that all of the participating institutions specialized in gastrointestinal diseases with more than 500 cases of ESD for EGC. Moreover, ESD for GTC may have been performed by leading specialists given the relative rarity of GTC. For these reasons, ESD for GTC seems safe if performed by specialists with sufficient ESD experience.

Previously, not a few patients had complications or died of other diseases during the course after esophagectomy[27,28]. However, due to the widespread use of minimally invasive esophagectomy, such as thoracoscopic and laparoscopic surgery, the incidence of postoperative complications, including respiratory complications, has decreased and the general condition of patients after esophagectomy has improved in recent years[29-32]. With continued improvements in the prognosis of esophageal cancer, the number of cases of GTC after esophagectomy will likely increase in the future and the demand for ESD for GTC is expected to increase further.

There were several limitations to this study. First, as this was a retrospective study, the ESD indications and devices used for treatment were not standardized. However, treatment was performed according to the typical standards. Second, since data on Helicobacter pylori infection status were missing in some patients, the association between GTC and Helicobacter pylori could not be evaluated. Third, as some patients were observed for only a short time, the assessment of long-term prognosis after ESD for GTC was insufficient. Further follow-up studies are needed in the future.

Figure 1 A case of subcutaneous abscess formation after perforation during endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer. A: Gastric tube cancer located at the anterior wall of gastric body; B: Marking dots were placed around the lesion, and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was performed as usual; C: Perforation occurred during ESD; D: Perforation was sealed immediately with 4 endoclips; E: Redness of the skin in the precordial area, 20 d after ESD; F: Computed tomography performed 20 d after ESD. A subcutaneous abscess (yellow arrow) had formed around the gastric tube of the antethoracic reconstruction route (orange arrow).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, ESD for GTC after esophagectomy is a safe and effective treatment that can be performed without significant variability in treatment results at any specialized institution where standard gastric ESD can be performed with sufficient expertise. Further accumulation and follow-up of cases of GTC are necessary in the future.

Figure 2 Overall survival curve after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer. The survival rate at 5 year was 59.5%. ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年11期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年11期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Chronic renal dysfunction in cirrhosis: A new frontier in hepatology

- Genotype 3-hepatitis C virus' last line of defense

- How to manage inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: A guide for the practicing clinician

- Study on the characteristics of intestinal motility of constipation in patients with Parkinson's disease

- Apolipoprotein E polymorphism influences orthotopic liver transplantation outcomes in patients with hepatitis C virus-induced liver cirrhosis

- Prospective single-blinded single-center randomized controlled trial of Prep Kit-C and Moviprep: Does underlying inflammatory bowel disease impact tolerability and efficacy?