Peritoneal dissemination of pancreatic cancer caused by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: A case report and literature review

Hideaki Kojima, Minoru Kitago, Eisuke Iwasaki, Yohei Masugi, Yohji Matsusaka, Hiroshi Yagi, Yuta Abe,Yasushi Hasegawa, Shutaro Hori, Masayuki Tanaka, Yutaka Nakano, Yusuke Takemura, Seiichiro Fukuhara,Yoshiyuki Ohara, Michiie Sakamoto, Shigeo Okuda, Yuko Kitagawa

Abstract

Key Words: Case report; Pancreatic carcinoma; Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration; Peritoneal dissemination; Cancerous peritonitis; Biopsy

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) is a type of biopsy procedure to collect tissue from mass lesions or body fluid inside and outside the gastrointestinal tract wall. It was first clinically used for pancreatic cancer in 1992 by Vilmannet al[1]and has been widely used for the qualitative diagnosis of pancreatic tumors, as it has a high sensitivity of 85%-92% and a high specificity of 96%-98% for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer[2,3]. The main indications of EUS-FNA are the differentiation of benign and malignant tumors, acquisition of histological evidence for introducing chemotherapy and selecting an appropriate drug regimen, and diagnosis of cancer progression. Considering recently developed therapies, such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy for pancreatic cancer, the need for collecting tissue samplesviaEUS-FNA will increase in the future[4-6]. EUS-FNA is a relatively safe method with few complications[7,8]. The incidence rate of complications is approximately 1%-2%, and complications mainly include abdominal pain, pancreatitis, hematoma, bleeding, fever, and abdominal discomfort. Although peritoneal dissemination and needle-tract seeding are rare events among the limited complications, they are an issue because they can influence patient prognosis. In this regard, previous studies concluded that EUS-FNA does not affect postoperative survival or peritoneal recurrence[9-11]. However, cases of dissemination or needle-tract seeding caused by EUS-FNA have been recently reported, with most cases being intragastric wall metastases due to needle tract seeding; peritoneal dissemination is rare[9,12-31]. Herein, we report a case of peritoneal dissemination of pancreatic cancer that was revealed to be caused by preoperative EUS-FNA based on pathological findings and resulted in radical disease progression, along with a review of the literature.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

An 81-year-old man was found to have a 16-mm hypodense mass lesion at the pancreatic tail region as well as dilation of the main pancreatic duct on undergoing computed tomography (CT) performed during the course of an annual medical checkup in Japan. The patient was then referred to the Department of Surgery for further examination and treatment.

History of present illness

The patient did not have any specific subjective or objective symptoms.

History of past illness

The patient had a history of diabetes.

Personal and family history

There was no family history of malignant tumors.

Physical examination

No jaundice or palpable masses were observed.

Laboratory examinations

A blood test revealed normal protein levels, including carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (15 U/mL; normal range, 0-37 U/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen (1.7 ng/mL; normal, < 5 ng/mL), s-pancreas-1 antigen (11 U/mL; normal, < 30 U/mL), duke pancreatic monoclonal antigen type 2 (< 25 U/mL; normal, < 150 U/mL), and elastase-1 (40 ng/dL; normal, < 300 ng/dL).

Imaging examinations

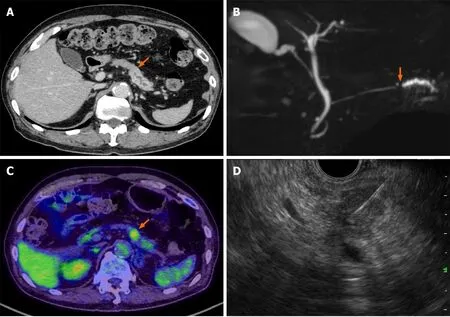

Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a pancreatic mass at the pancreatic tail region with a prolonged contrast effect, as well as dilation of the main pancreatic duct (Figure 1A and B). Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) revealed abnormal accumulation of fluorodeoxyglucose in the same lesion (Figure 1C). These findings were strongly suspected to be pancreatic cancer and associated obstructive pancreatitis; however, there remained a possibility that the tumor was benign, such as mass-forming pancreatitis or autoimmune pancreatitis.

FURTHER DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP

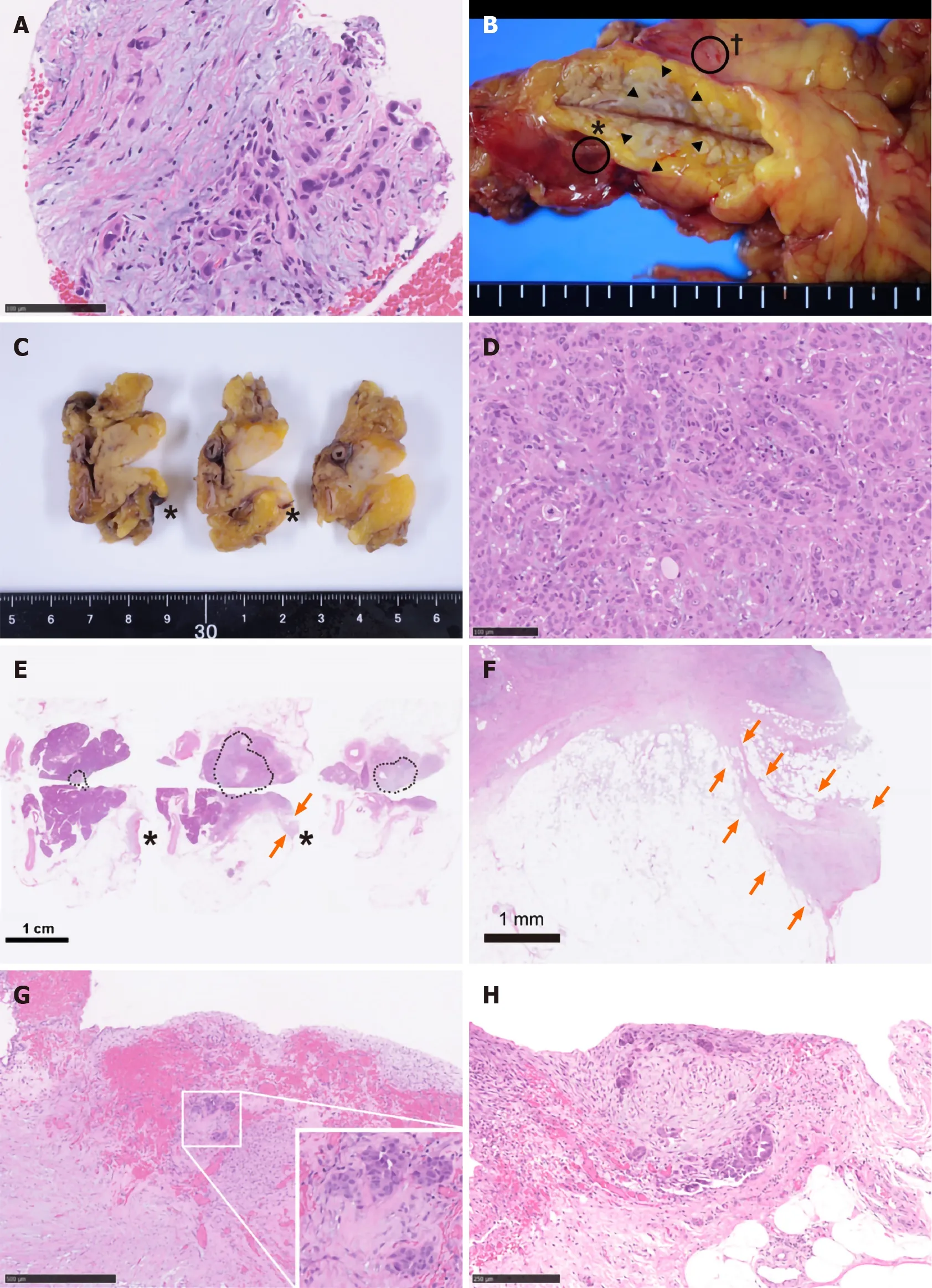

Hence, trans-gastric EUS-FNA was performed with a 22-gauge needle to obtain a qualitative diagnosis by an experienced gastroenterologist. During the procedure, the needle passed four times through the gastric wall. Tumor tissue was then successfully collected, with no early complications (Figure 1D). The pathological findings indicated a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Figure 2A). PET-CT and contrast-enhanced CT scans showed no evidence of distant metastasis, no infiltration into the anterior or posterior adipose tissue, and no involvement of the major arteries (celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery, common hepatic artery) or veins (superior mesenteric vein, portal vein) in the tumor. The preoperative diagnosis was pancreatic invasive ductal adenocarcinoma, cT1c, cN0, and cM0 cStage IA, per both the 7thedition of the Japanese Pancreas Society classification (JPS 7thed) and the 8thedition of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC 8thed). After establishing the diagnosis, laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with lymphadenectomy was performed. No intraoperative peritoneal dissemination and liver metastasis were visually observed, and pelvic lavage cytology was negative for carcinoma cells (P0, CY0). The pancreatic tumor did not invade the surrounding organs or adipose tissue, which was confirmed by intra-operative ultrasound examination of the pancreas. The operation was successfully performed as planned without exposing the tumor during surgery. The patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery and was discharged on postoperative day 13. The final pathological findings revealed that the dissected and cut end margins were negative for carcinoma cells. The tumor was observed to be a poorly circumscribed whitish mass that was located within the pancreatic parenchyma, and direct infiltration into the anterior and posterior adipose tissues was not observed (Figure 2B). There were two areas of peritoneal thickening with reddish and whitish appearance at a distance from the main tumor site, where a trabecular fibrotic scar associated with peritoneal surface hemorrhage owing to needle punctureviaEUS-FNA was observed under a high-power view (Figure 2B, E and F). In this area, small aggregates of tumor cells were observed that were similar to those of the main tumor, indicating that these tumor cells were disseminatedviaEUS-FNA from the main lesion (Figure 2D, G and H).

Figure 1 Pre-operative imaging findings. A: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showing a hypodense mass lesion (arrow) in the pancreatic tail region as well as dilation of the main pancreatic duct; B: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showing obstruction (arrow) and dilation of the main pancreatic duct; C: Positron emission tomography-CT scan showing the high uptake (arrow) of fluorodeoxyglucose by the pancreatic tail mass; D: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration performed using a 22-gauge needle through the posterior gastric wall.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis was Pt, TS1 (13 × 12 × 10 mm), infiltrative, ductal adenocarcinoma, pT1c, int, INFc, ly1, v3, ne1, mpd0, pS0, pCHX, pDUX, pPVsp0, pAsp0, pPL0, pPCM0, pDPM0, N1a (1/36, #11p), M1 (P), pStage IV (JPS 7thed) and pT1c, pN1, and pM1 pStage IV (UICC 8thed).

TREATMENT

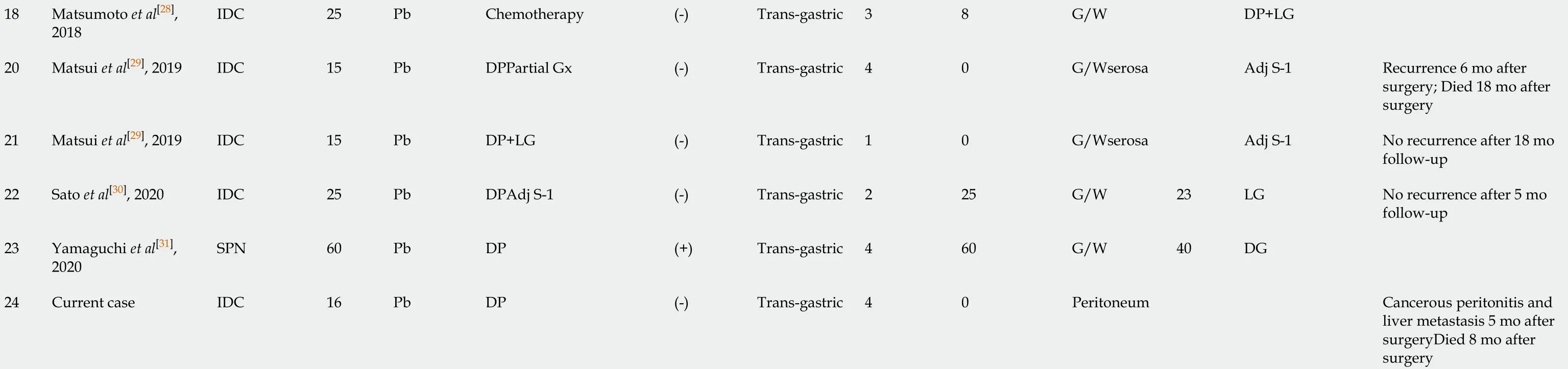

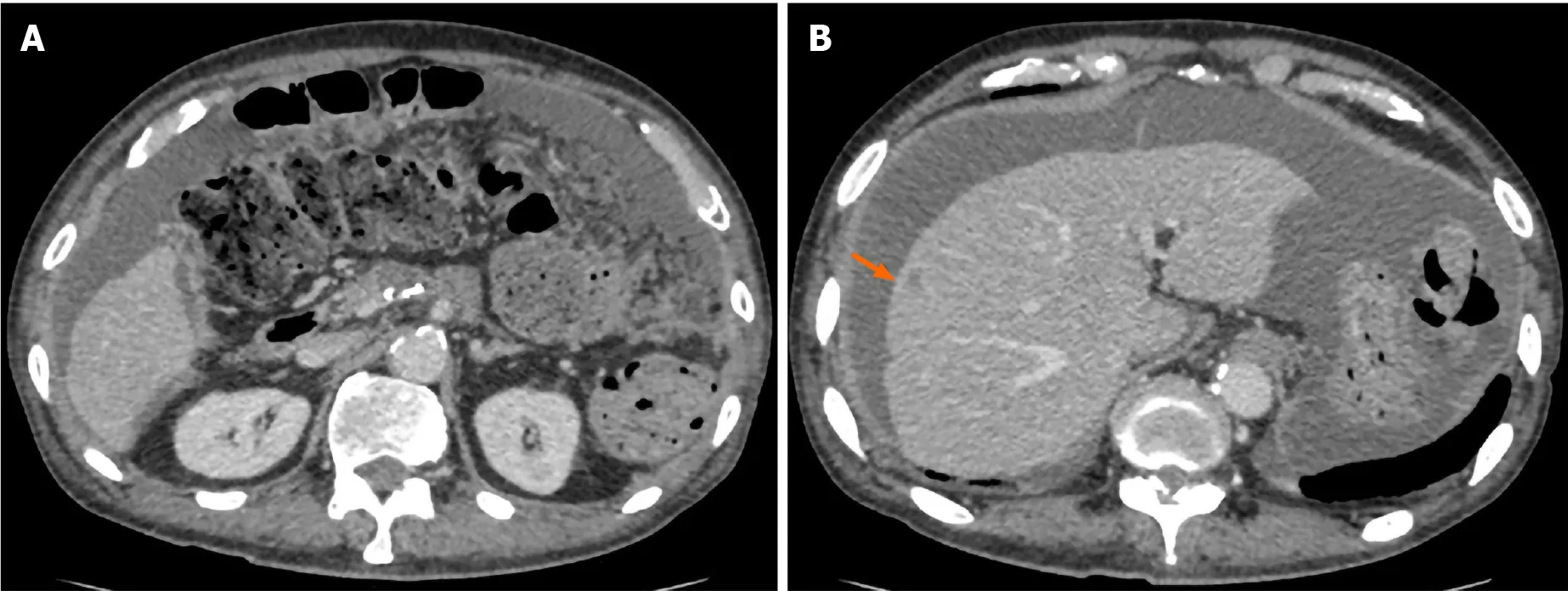

Accordingly, the patient underwent adjuvant therapy with S-1 (tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil potassium). However, a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis obtained 5 mo after the operation revealed liver metastasis and cancerous peritonitis (Figure 3). The patient was offered a more effective chemotherapy regimen for recurrent pancreatic cancer; however, he did not want further treatment.

Figure 2 Pathological findings. A: Specimens obtained via endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) biopsy. Atypical cells with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei infiltrating the fibrous stroma are visible; B: A fresh gross image of the resected pancreas: a poorly circumscribed whitish tumor mass (arrowheads) is observed within pancreas parenchyma at the cut surface. Two areas of peritoneal thickening with reddish (asterisk) and whitish (dagger) appearance are observed at a distance from the tumor site; C: The cut surface of the formalin-fixed specimen: the peritoneal side is on the right, and the retroperitoneal side on the left; D: Histological image of the main tumor: the tumor is predominantly composed of poorly differentiated carcinoma cells with ill-defined ductular structures; E: A loupe image correspondence to the macroscopic image observed in panel C: the area surrounded by black dots is the main tumor lesion. A trabecular fibrotic scar (arrows) associated with peritoneal surface hemorrhage (asterisks) is observed; F: A low-power view of the fibrotic scar (arrows in E) possibly due to the needle tract injected during EUS-FNA; G: A high-magnification image of hemorrhagic peritoneum (asterisks in B, C, and E) proximal to the fibrotic scar. In this area (considered to be the needle puncture site), small aggregates of tumor cells (inset) are embedded in the fibrotic stroma; H: A high-power microscopic view of the whitish thickened peritoneum (dagger in B). Disseminated tumor cells focally forming the ductular structures are seen on the surface of the serosa.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

He received palliative therapy and died 8 mo after the operation.

掌握一个词不仅要知道这个词的字面意义,还要掌握该词的多层意思、该词的运用有何限制、该词的转化词、该词的句法特征、语义特征及相关的搭配等。[6]所以单单靠死记硬背词汇表的方法是学不好词汇的。

DISCUSSION

Peritoneal dissemination or needle-tract seedingviaEUS-FNA is an issue because it impairs patient survival. However, the frequency of dissemination is extremely low. Moreover, several studies have evaluated the long-term prognosis of patients with pancreatic cancer; the results showed that EUS-FNA was not associated with recurrence in the gastric or peritoneal wall or with overall survival of patients who underwent resection for pancreatic cancer[9-11]. Similar to the results of previous studies, Yaneet al[32]reported that EUS-FNA does not affect recurrence-free survival and overall survival. However, the authors also mentioned non-negligible effects of needle-tract seeding after EUS-FNA as 6 of 176 (3.4%) patients had recurrences in the intra-gastric wall[32]. Furthermore, some researchers have indicated that EUS-FNA might promote distant metastasis by blood dissemination and puncture dissemination. Levyet al[33]analyzed cell-free DNA (cfDNA) before and after EUS-FNA of pancreatic adenocarcinoma to assess the risk of the distant metastasis due to EUS-FNA. cfDNA is the nuclear material from a tumor that disseminates into the bloodstream (tumoremia); it has been developed a useful biomarker for various tumors (including pancreatic cancer) to predict the therapeutic response and prognosis[34,35]. Levyet al[33]reported an insignificant increase in the plasma concentration of cfDNA and increased detection ofKRASmutations in cfDNA after EUS-FNA. Additionally, a significant number of new distant metastases were detected in patients with tumoremia. Although the study was a preliminary evaluation with only a small number of patients, the findings suggest that EUS-FNA might contribute to increased distant metastases. Accordingly, we are planning to evaluate cfDNA in preserved plasma from the case presented in this report.

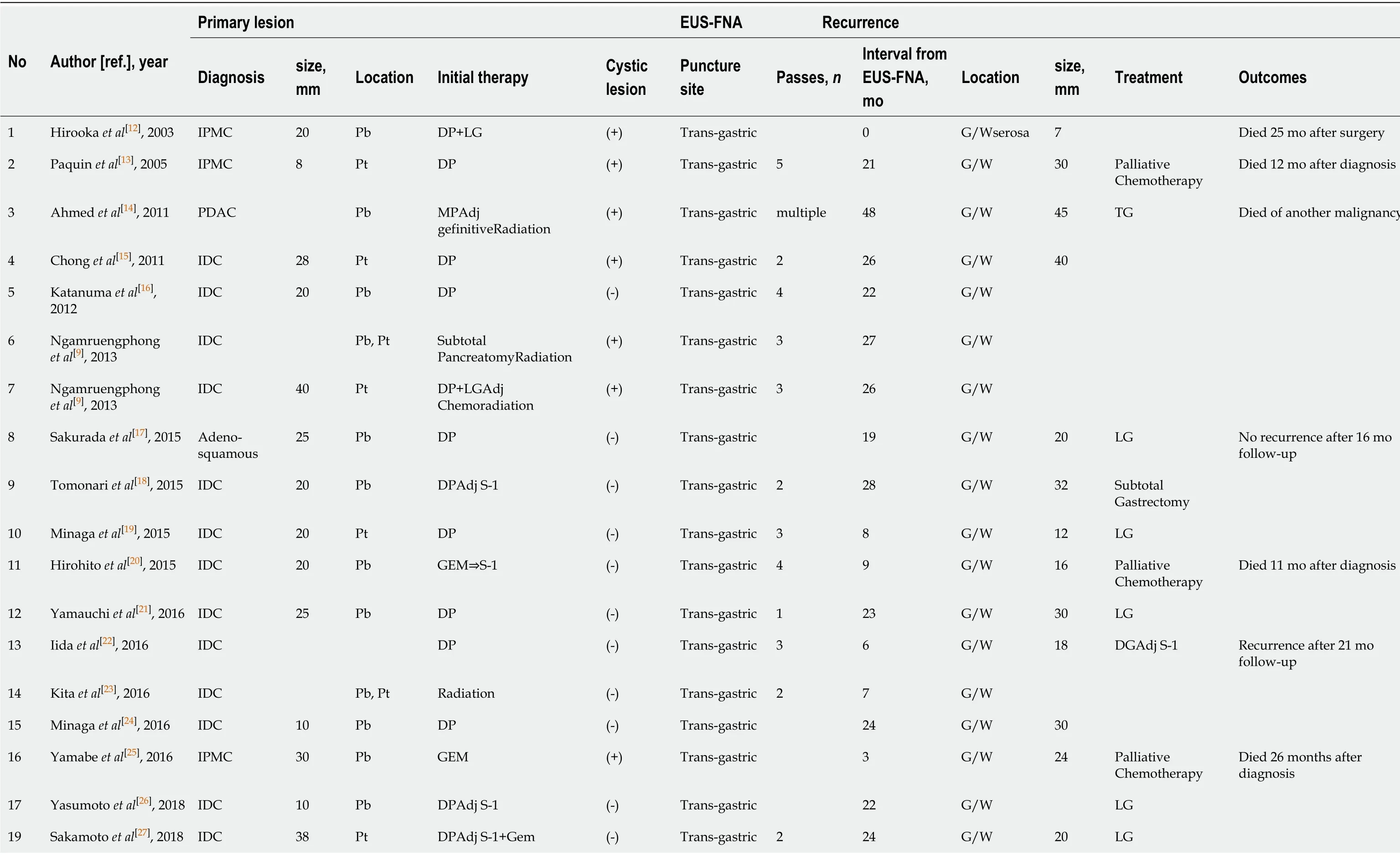

Considering the findings of these studies, the frequency of dissemination and needle-tract seeding due to EUS-FNA appears to have been underestimated. There are several possible causes of underestimation, as clarified in the previously reported 24 cases including the present case (Table 1). First, upper endoscopy is not performed, and EUS-FNA puncture sites are not examined if patients have no symptoms. Second, the needle tract could be also resected with the main tumor lesion; hence, dissemination does not tend to be evaluated. Third, peritoneal dissemination may be unlikely in cases of pancreatic head tumors, because there is no space between the pancreatic head and the duodenum. Finally, it is difficult to distinguish between procedure-related dissemination and disease progressionviaimaging. These reasons may explain why most cases reported needle-tract seeding into the intra-gastric wall and not the peritoneal wall, and there was no case of the primary tumor being in the pancreatic head. From a prognostic point of view, additional gastrectomy seemed to be effective for cases of intra-gastric wall recurrence[17,29,30]; therefore, the puncture site should be regularly investigated postoperatively, and surgical intervention should be considered in cases of local recurrence. In contrast, some cases develop inoperative short-term recurrences[25], as observed in the current case. Therefore, the indications for a trans-gastric biopsy from the pancreatic body and tail should be carefully considered before being performed. Cumulative case reports and a large prospective cohort study are needed to clarify the frequency of procedure-related dissemination and its effect on long-term outcomes.

To the best of our knowledge, the current case is the first report in which peritoneal dissemination associated with EUS-FNA was pathologically proven by using a postoperative specimen. In the current case, some small peritoneal disseminations were observed that were discontinuous from the main lesion. Similar pathological findings and dismal prognoses have been observed in cases of intra-pancreatic metastasis or multi-centric carcinogenesis[36,37]. Therefore, if a small cancerous lesion is observed within the pancreatic parenchyma, it needs to be differentiated from needle tract seeding. Unlike previous reports that state that preoperative EUS-FNA does not affect the prognosis, the current patient showed aggressive disease progression. Although the liver metastasis might be explained by the high degree of pathological vascular invasion, it is clinically unusual to present with such acute cancerous peritonitis when the intra-operative cytology results were negative for carcinoma cells. In addition to the pathological findings, the unusual disease progression is also consistent with EUSFNA-related dissemination.

Table 1 Clinical features of 24 previous cases of dissemination after endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration

EUS-FNA: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration; IDC: Invasive ductal carcinoma; IPMC: Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma; SPN: Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm; Pb: Pancreatic body; Pt: Pancreatic tail; DP: Dist pancreatectomy; MP: Middle pancreatectomy; LG: Local gastrectomy; DG: Distal gastrectomy; TG: Total gastrectomy; Adj: Adjuvant; S-1: Tegafur, gineracil, oteracil potassium; GEM: Gemcitabine hydrochloride; G/W: Gastric wall.

EUS-FNA is widely used when it is difficult to distinguish between benign and malignant tumorsviaimaging, because it helps to avoid unnecessary surgery. In addition, EUS-FNA is recommended for both resectable cases and unresectable advanced cases because a histological diagnosis is needed to select an appropriate drug regimen for neoadjuvant chemotherapy or palliative chemotherapy. However, it is not always necessary to obtain a definitive preoperative pathological diagnosis when the tumor is strongly suspected to be pancreatic cancer and when up-front surgery has been already planned.

This case highlights the importance of recognizing the risk of disease dissemination associated with EUS-FNA. Thorough discussion should be conducted on individual cases prior to performing EUS-FNA.

CONCLUSION

The indications for EUS-FNA should be thoroughly discussed with radiologists and endoscopists to avoid iatrogenic dissemination, especially for cancers in the pancreatic body or tail. In addition, careful observation is required not only of the surgical site but also of the puncture site.

Figure 3 Computed tomography obtained 5 mo after surgery. An ascites associated with cancerous peritonitis and liver metastasis (arrow) was observed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Kazumasa Fukuda, a staff member of the Department of Surgery at Keio University School of Medicine, for her help in preparing this manuscript.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年3期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年3期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Comparative study on artificial intelligence systems for detecting early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma between narrow-band and white-light imaging

- Trends in the management of anorectal melanoma: A multi-institutional retrospective study and review of the world literature

- Serum vitamin D and vitamin-D-binding protein levels in children with chronic hepatitis B

- Circular RNA AKT3 governs malignant behaviors of esophageal cancer cells by sponging miR-17-5p

- Screening colonoscopy: The present and the future