Lingual lymph nodes: Anatomy, clinical considerations, and oncological significance

Shalva R Gvetadze, Konstantin D Ilkaev

Shalva R Gvetadze, Konstantin D Ilkaev, Central Research Institute of Dentistry and Maxillofacial Surgery, Moscow 119991, Russia

Konstantin D Ilkaev, Blokhin National Medical Research Center of Oncology, Moscow 115478,Russia

Abstract Lingual lymph nodes are an inconstant group of in-transit nodes, which are located on the route of lymph drainage from the tongue mucosa to the regional nodes in neck levels I and II. There is growing academic data on the metastatic spread of oral cancer, particularly regarding the spreading of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma to lingual nodes. These nodes are not currently included in diagnostic and treatment protocols for oral tongue cancer. Combined information on surgical anatomy, clinical observations, means of detection, and prognostic value is presented. Anatomically obtained incidence of lingual nodes ranges from 8.6% to 30.2%. Incidence of lingual lymph node metastasis ranges from 1.3% to 17.1%. It is clear that lymph nodes that bear intervening tissues from the floor of the mouth should be removed to improve loco-regional control.Extended resection volume, which is required for the surgical treatment of lingual node metastasis, cannot be implied to every tongue cancer patient. As these lesions significantly influence prognosis, special efforts of their detection must be made. Reasonably, every tongue cancer patient must be investigated for the existence of lingual lymph node metastasis. Lymphographic tracing methods,which are currently implied for sentinel lymph node biopsies, may improve the detection of lingual lymph nodes.

Key words: Lingual lymph node; Sublingual lymph node; Tongue cancer; Regional metastasis; Lymph drainage; Head neck region; En-bloc resection

INTRODUCTION

Oral cavity carcinoma is a common malignant neoplasm with over 400000 cases detected annually worldwide. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most frequent form, accounting for around 90% of malignancies found in the oral cavity region.Among anatomical subsites of the oral cavity, the highest incidence of SCC affection was reported for oral tongue (35.3%)[1-3]. The prognosis for subjects with oral SCC relies of tumor- and host-related features, as well as treatment variations. N stage is deemed to be the most significant predictive factor, since the existence of a single metastatic node in the regional lymphatic basin at referral creates a 50% drop in 5-year survival[4]. SCC has a high potency for regional lymphogenic spread to the neck lymph nodes. Regional lymphatic drainage pathways are well recognized in the head and neck regions, and on this basis, several neck dissection modifications have been elaborated. For oral tongue SCC, the submental, submandibular, and jugulodigastric lymph nodes are known to be the first echelon of draining nodes.

In 1985, Ozekiet al[5]documented lingual lymph nodes (LLNs) as possible sites of metastatic spread for oral tongue SCC. Although anatomical descriptions have long been available in the literature, this paper had first drawn attention due to this inconstant group of lymph nodes in terms of tongue cancer progression. Up until now, considerable clinical data has accumulated on LLN metastasis. The purpose of this paper is to overview the anatomy, the current clinical experience in detection and treatment of metastasis to LLNs, and its influence on survival and prognosis.

Literature sources on LLN metastasis were searched in both PubMed and Google Scholar. As initial clinical descriptions of LLN metastasis were reported by Japanese authors, searches in the J-STAGE scientific database were employed. The heading and key words “lingual lymph node”, “sublingual lymph node”, “tongue cancer”,“regional metastasis”, and “lymph drainage” were used for exploration. The obtained articles were separated into two groups: One including case reports, and one including clinical series and trials related to LLNs. Subject details, tumor stage and characteristics, LLN involvement, treatment modes, and follow-up results were collected from the case report group. In the clinical series and trials group, the following information was acquired: Diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations,survival scores, and prognostic value for patients with LLN lesions.

The review included 27 evaluable papers on LLN metastasis from oral SCC in the form of case reports or clinical series and trials published between 1985 and 2020. The summarized data are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

ANATOMY

LLN classification

One of the earliest references to LLNs are found in Kuttner’s work on tongue cancer spreading to regional lymph nodes, wherein he illustrated that up to three nodes localized near the sublingual salivary gland[6]. Traditional classification of LLNs,which is still generally applied today, was proposed by Rouviere[7]in 1938. In the classic tutorialAnatomy of the human lymphatic system, he grouped LLNs as rare median and more prominent lateral. In a study of embryos, Katayama found that the incidence of median LLNs is 15.1% and lateral LLNs is 30.2%[8]. In an anatomical study of 104 adult cadavers, LLNs were observed within the tongue musculature in 8.6%, and were outlined as regional draining lymph nodes of the tongue[9]. Later, the LLNs were termed as “interrupting nodules”, which are situated along the collecting lymphatic trunks of the tongue and the sublingual gland as an insertion on thelymphatic flow pathway to levels I and II[10]. Shelomentsev and Sushentsov (1975)documented the close connections of lingual lymphatic vessels to the sublingual salivary gland. Lingual lymphatics were shown to pass through the sublingual gland parenchyma and drain it. The authors discovered that the major lingual efferent lymphatic trunks are located along the lingual vein in the sublingual and upper neck regions[11]. Ananianet al[12]reported a 23.8% incidence of lateral LLNs, and further divided them into parahyoid and paraglandular nodes according to their position. No median LLNs were identified. Median LLNs were spotted as rare as 0.95% in a large imaging series[13]. Surgical-anatomical classification of LLNs was proposed by Suzukiet al[14], where LLNs were distributed into four subgroups: Median LLNs, anterolateralLLNs (located in proximity to the sublingual gland), parahyoid LLNs (located along the greater cornu of the hyoid bone), and posterolateral LLNs. This group consists of one or two small lymph nodes outside the sublingual and floor of the mouth regions.These nodes reside between the posterior edge of the mylohyoid and the inner surface of the submandibular gland. In a study by DiNardoet al[15], this lymph node was depicted in detail earlier and termed as thedeep submandibular node. It was proposed that this node is located along the course of the lymph drainage route that is directed straight to level II from the tongue margin mucosa[16]. These works were based on clinical observations of metastatic spread. The precise affiliation of this node is debatable, since it topographically belongs to the submandibular space, which is outside the sublingual and floor of the mouth regions. On the other hand, relevant anatomical material was recently published by Eguchiet al[17]. During gross dissection,the authors managed to identify a thin fascial lamina located deep to the submandibular salivary gland that covered the hyoglossus muscle and the lingual and hypoglossal nerves. It was stated that this fascial layer is distinct from the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia, which splits to envelope the superficial and deep surfaces of the submandibular gland. The authors assumed that the posterolateral LLN or deep submandibular node is also covered by that facial layer,which in turn extends to the sublingual region. These nodes therefore may be anatomically related to the LLN group[17]. Further micro- and macroscopic research of the floor of the mouth and submandibular triangle anatomy is needed to clarify this controversial issue.

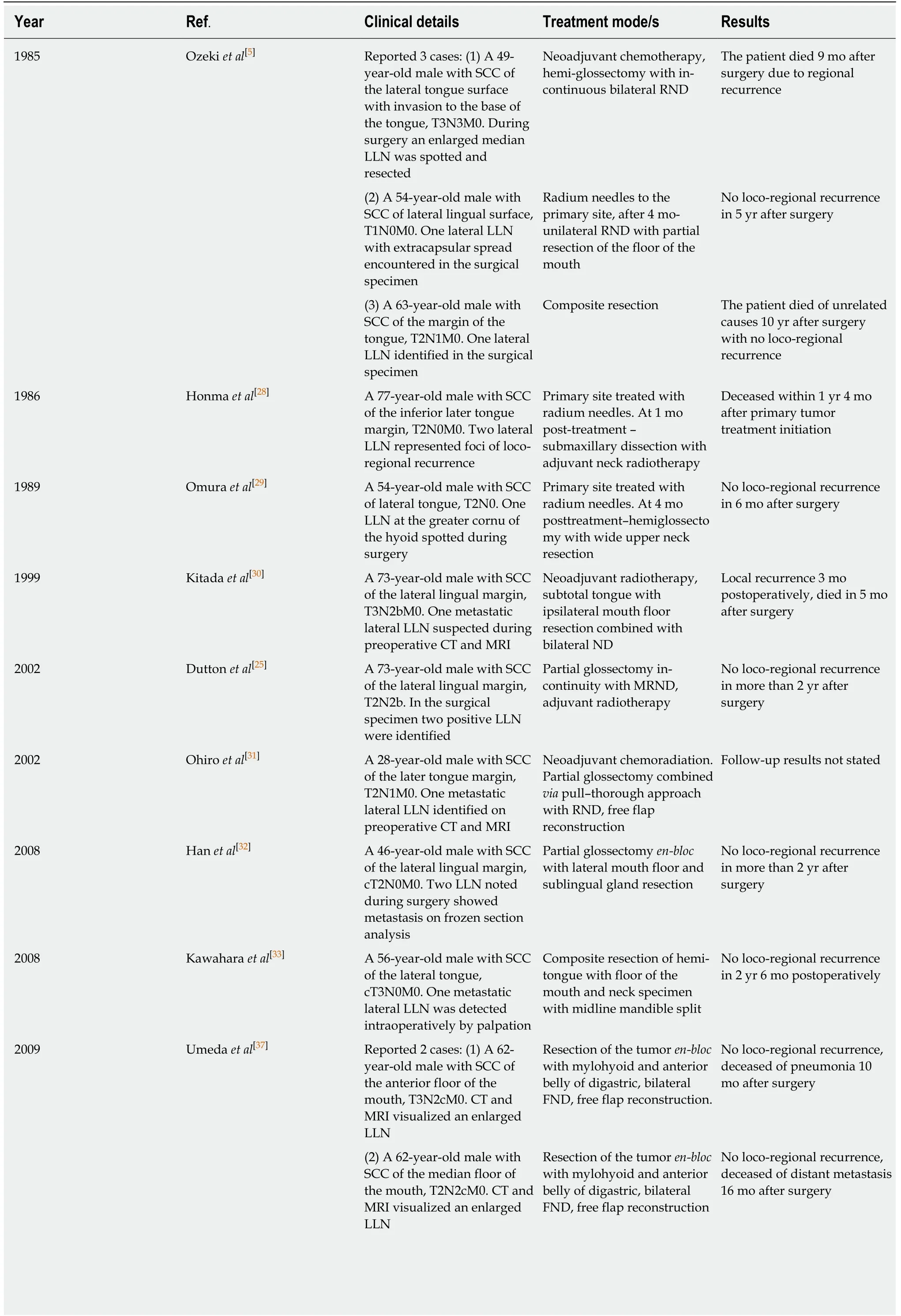

Table 1 Case reports of lingual lymph node lesions

LLNs: Lingual lymph nodes; SCC: Squamous cell carcinoma; ND: Neck dissection; RND: Radical neck dissection; MRND: Modified radical neck dissection;MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; CT: Computed tomography.

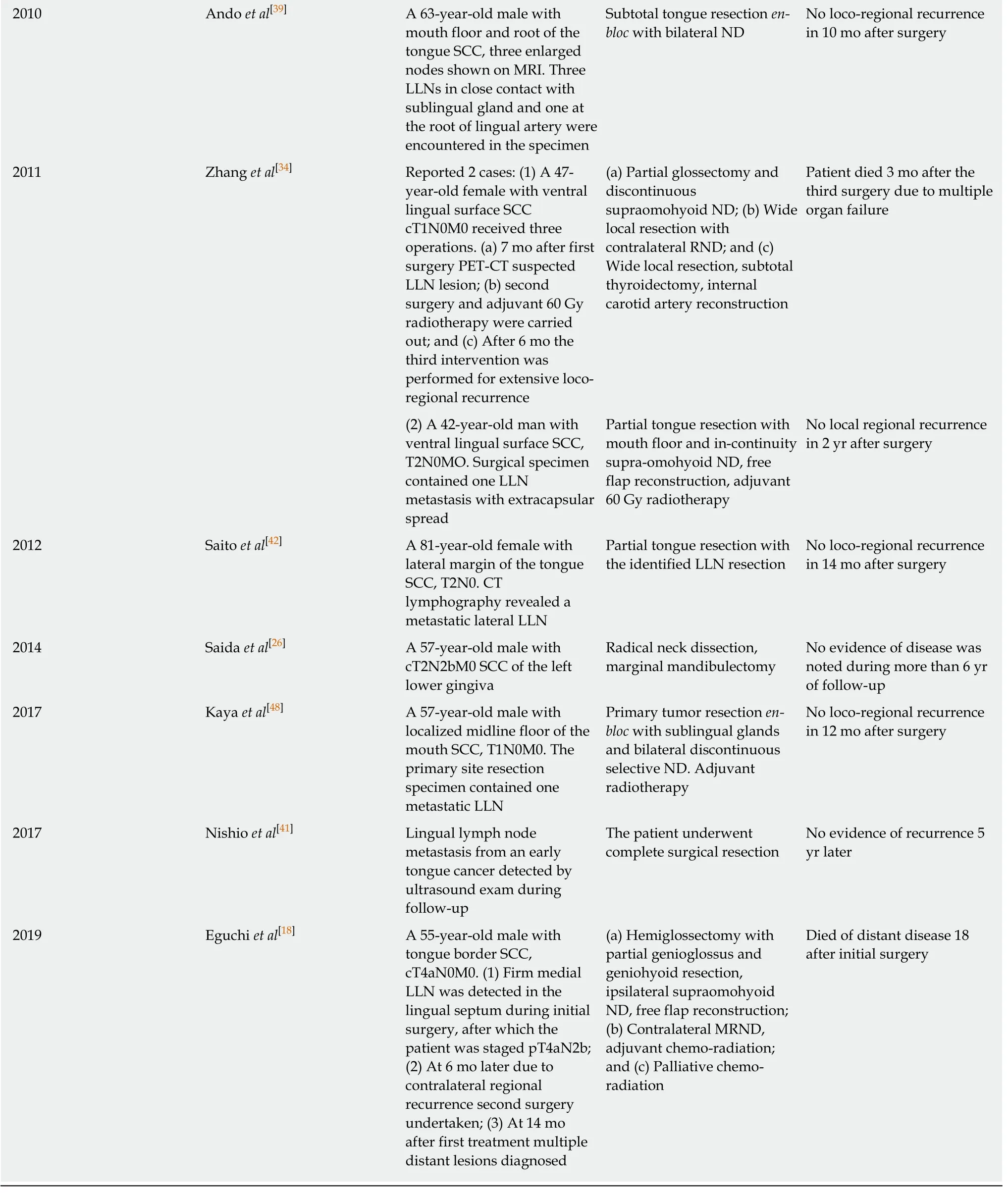

Table 2 Clinical series related to lingual lymph nodes

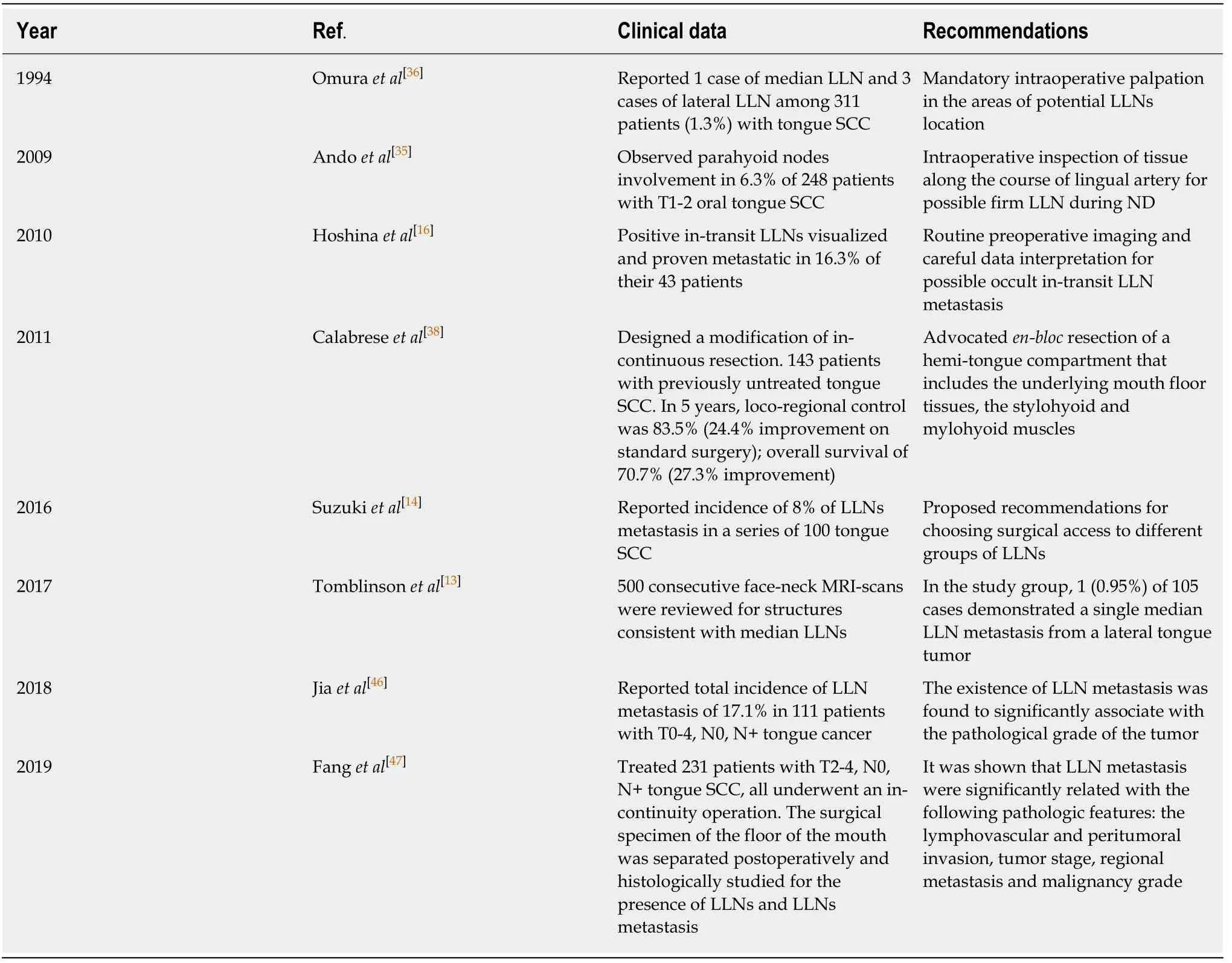

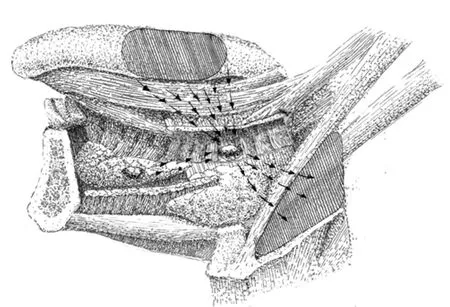

Spatial arrangement of the floor of the mouth

For a clear understanding of the LLN location, the presentation of the spatial arrangement of the mouth floor is valuable (Figure 1). The floor of the mouth region is composed of five intermuscular gaps; these include one unpaired median gap, and two paired later spaces, the floor for them all of which is constituted by the upper surface of mylohyoid muscles. The median or central space lies in between the inner surfaces of the genioglossal and geniohyoid muscles. Anteriorly, it is bounded by the medial aspect of the mandibular lingual cortical plate and anteromedially by tendinous muscular attachments to the mental spine. Posteriorly, the space is continuous with the fatty tissue of the root of the tongue. This space is enclosed by skeletal muscles and has no connections with both lateral spaces. Median LLNs may be contained in this space on each side of the lingual septum in a sagittal position of three-fourth of the distance from the mental spine[18]. Moving outwards, the intermediate lateral space is encountered. This lies surrounded by the lateral surfaces of the genioglossal and geniohyoid, and the medial surface of the hyoglossal muscle.Anteriorly, it is continuous with the lateral gap of the floor of the mouth, and posteriorly, the areolar tissue extends into the parapharyngeal space. The lingual artery travels along this anatomical space, and here the lateral parahyoid LLNs can be found at the great cornu of the hyoid bone. The third space is anteriorly and laterally limited by the lingual cortical plate of the mandible and the sublingual fossa of the mandible. Anteromedially, the space is bounded by the anterior division of the genioglossal and the geniohyoid muscles. Posteromedially, it opens into the intermediate lateral space of the mouth floor. Posterolaterally, it extends into the submandibular spaceviathe aperture between the mylohyoid and hyoglossal muscles. This space harbors the following structures: Deep lingual vein, hypoglossal,lingual and mylohyoid nerves, deep lobe of the submandibular salivary gland,submandibular duct, and sublingual salivary gland[19,20]. The lateral paraglandular LLNs lie in this space adjacent to the sublingual salivary gland.

Lymphatic drainage pathways

The lymphatics from the anterior two thirds of the tongue (the oral portion) may be divided into two divisions: Marginal and central vessels[21,22]. The marginal vessels receive lymph from the outer one third of the upper surface of the tongue, the marginal surface, and tissues close to the sublingual region. The more anterior marginal vessels originate behind the tip of the tongue, pass laterally downward and through the mylohyoid muscle to finish in the submental nodes, or are addressed towards the submandibular nodes. The posterior marginal lymphatics direct downward and laterally pass the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle to reach the deep cervical lymph nodes. The central group of vessels situated at the tip of the tongue proceed through the mylohyoid muscle to drain into the submental nodes(level IA). Less commonly, lymphatics may course caudally across the hyoid bone to join nodes of the deep cervical chain, which particularly include the jugulodigastric and rarely the jugulo-omohyoid nodes. The central route from the remainder of the upper surface of the tongue runs mainly between the genioglossus and geniohyoid muscles towards the submental, submandibular nodes, or avoiding these groups that connect directly to the upper deep cervical nodes. The mylohyoid muscle is penetrated by the lymphatic vessels that run to the regional lymphatic basin from the tongue and floor of the mouth in two locations, the anterior and posterior portions of the muscle, thus connecting oral mucosa lymphatics with levels I, II and III[15,23,24].

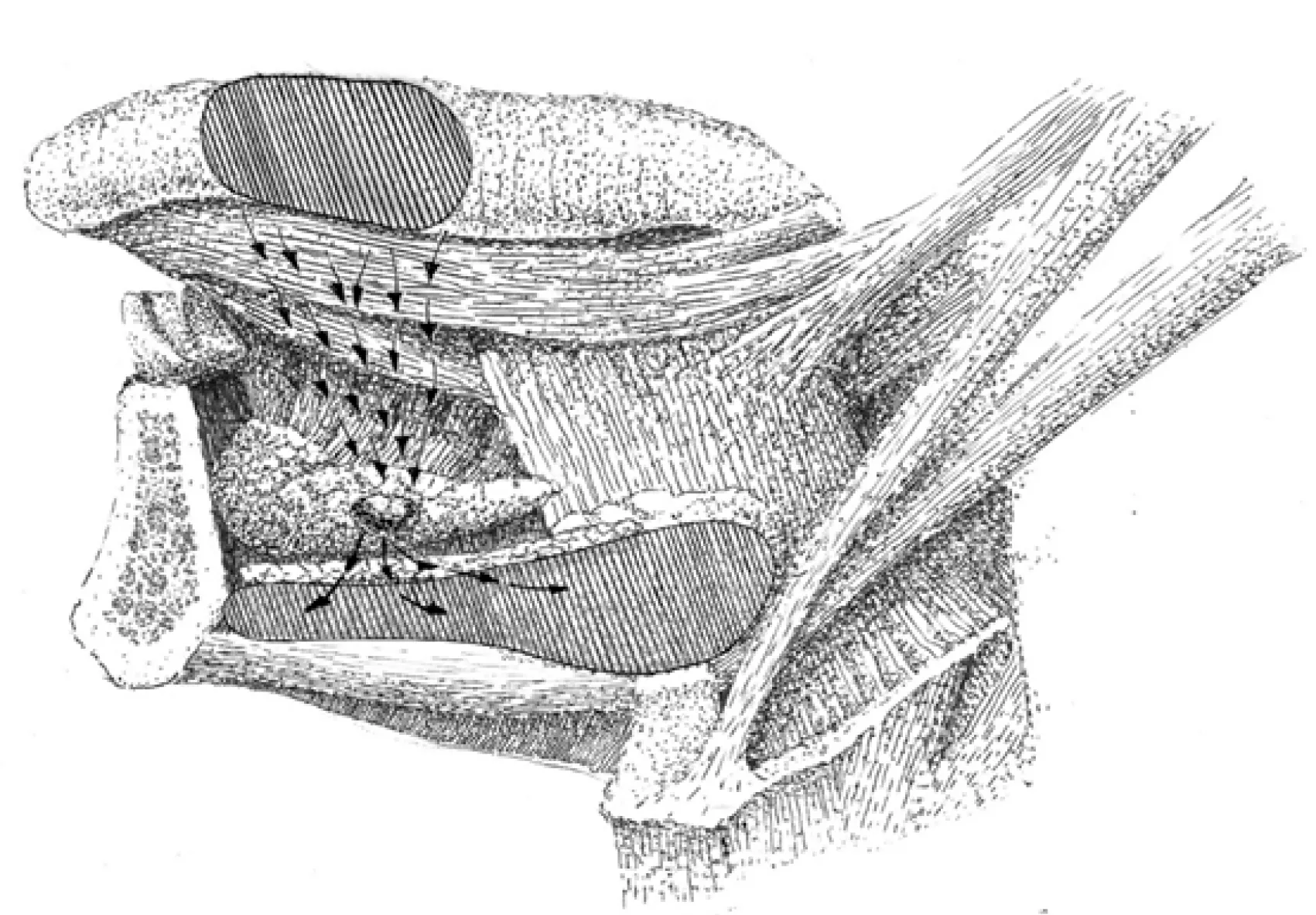

According to the interposition of LLNs on the lymphatic route from the primary site in the tongue to the regional nodes in levels I and II, they were termed as intervening[25,26], in-transit[16], and intercalated[27]in the literature. Generally, there are two main lateral directions of lymph transit from the oral tongue mucosa, which are anatomically delineated by the plane of the mylohyoid muscle. In the route of these two drainage pathways, lateral LLN may function as in-transit intermediary lymphatic elements[10]. The first pathway leads straight to level I through the mylohyoid muscle and further continues to levels II or III. The anterolateral or paraglandular LLNs may reside between the primary site in the anterior part of the tongue and level I (Figure 2). The second pathway is directed more horizontally and backward toward level II, specifically to the jugulodigastric node. This route runs along the upper surface of the mylohyoid (without penetrating it) towards the hyoglossus muscle and the greater cornu of the hyoid bone, and drains into level II nodes. It may in some instances incorporate a paraglandular LLN, but it is more probable to occur in the posterolateral or parahyoid LLN as well as the deep submandibular in-transit node, which were described by Hoshinaet al[16]as located on the course to level II (Figure 3). The central drainage pathway courses along the midline and spreads bilaterally towards levels I and II, depending on the sagittal position of the primary site. If present, the median LLNs receive lymph before it transcends the mylohyoid muscle and drains into regional lymph nodes[15].

Figure 1 Intermuscular spaces in the floor of the mouth. The median LLNs are situated in the central unpaired space, and the anterolateral (paraglandular) and posterolateral (parahyoid) nodes are located in the intermediate and outmost lateral spaces.

CLINICAL EXPERIENCE

Case reports and series

The first three observations of tongue SCC with metastasis to the lateral and median LLN were described by Ozekiet al[5]. This was followed by case reports of LLN involvement detected in different clinical settings: As loco-regional recurrence[28],during surgery[29], and on preoperative CT and MRI[30,31]. Only two out of the six subjects with LLN lesions had survived recurrent-free during the stated follow-up period. Both of these patients received radium needle treatment for the primary tumor and an in-continuous surgery with wide floor of the mouth and upper neck resection. Duttonet al[25]suggested a local resection of the mouth floor in combination with partial glossectomy for oral tongue SCC with risk for LLN involvement as a potential substitute for an in-continuity surgical approach. The lateral anatomical space of floor of the mouth can be accessed intra-orally and dissected simultaneously to glossectomy. With such access, the sublingual gland is removed inen-blocfashion with sublingual loose fatty tissue. Hanet al[32], Kawaharaet al[33], and Zhanget al[34]reported successful surgical treatment that incorporated hemi- or partial glossectomy combined with sublingual gland and floor of the mouth resection in 3 N0 patients with lateral LLN metastasis. Andoet al[35]was the first to distinguish the parahyoid group of LLNs. Located at the root of the lingual artery close to the cornu of the hyoid bone, these were observed to harbor tongue SCC metastasis in 6.3% of their 248 patients. This incidence was significantly higher than that reported in previous work,which ranged between 1.3%-2.1%[5,36]. It was suspected that small LLN size and their anatomical contiguity to the primary tumor precludes accurate in-time identification of LLN as a focus of metastasis or recurrence. This may also explain why there have only been two reported descriptions of LLN metastasis of SCC of the floor of the mouth[37]. Hoshinaet al[16]observed lateral LLN metastasis in 16.3% of 43 patients with tongue SCC. Suzukiet al[14]reported an 8% incidence of LLN metastasis in a series of 100 tongue SCCs, and proposed recommendations for choosing surgical access to different LLN groups. The anterolateral paraglandular nodes are accessed intraorally,the posterolateral parahyoid node resection requires additional dissection of the tissue at the greater cornu of the hyoid close to the parapharyngeal space, and the deep submandibular node should be removed during neck dissection together with the submandibular salivary gland. It is evident that the lymph node bearing intervening tissues of the floor of the mouth should be removed to improve loco-regional control.A modification of an in-continuous approach, which is based on a principle of fascial tongue compartments, was designed by Calabreseet al[38]. The authors performed a wide resection of a tongue compartment that included the adjacent floor of the mouth,mylohyoid, and stylohyoid muscles. In a study of 143 subjects with cT2-4a, cN0, cN+,and M0 tongue SCC, they reported 16.8% improvement in local control, 24.4%improvement in loco-regional control, and a 27.3% improvement in overall survival compared to standard surgery. Median LLN metastasis was very rarely observed.Eguchiet al[18]summarized the details of seven published cases of median LLN metastasis secondary to tongue SCC, and presented one new case. It was concluded that median LLN lesions are strongly associated with bilateral metastatic spread.

LLN detection

Figure 2 Lymph drainage direction toward the paraglandular LLNs. The paraglandular LLN lies in an in-transit position of the lymph flow (arrows) from the oral tongue mucous membrane to regional level I.

Detection of LLN metastasis is a crucial but most often neglected part of diagnosis and surgical treatment planning, especially in otherwise cN0 patients. Reasonably,every patient with tongue cancer must be investigated for the presence of LLN lesions. Preoperative palpation may bring out a suspicion of firm LLNs: Median and anterolateral paraglandular LLN lesions are palpated intraorally along the median and lateral aspects of the sublingual region; posterolateral LLN lesions are bimanually accessed and palpated in the mandibular-lingual groove. Attentive palpation at the area of the greater cornu of the hyoid bone and along the lingual vessels course helps to intraoperatively detect LLN metastasis during neck dissection[29,35,36].

LLNs are an inconstant lymph node group with an extended surgical volume that is required for the surgical treatment of LLN metastasis, which cannot be implied for every tongue cancer patient. Anatomically-obtained incidences of LLN range from 8.6% to 30.2%[8,9,12]. This necessitates the performance of various preoperative imaging modes with consequent meticulous data analysis. CT and MRI were reported to be effective for LLN metastasis visualization in cN+ staged cases[30,31,37,39]. Several researchers outlined the benefits of combining preoperative contrast-enhanced CT and MRI (central necrosis and/or extracapsular spread are usual findings in LLN metastasis), and postoperative ultrasound monitoring (every month follow-up)[40,41].Saitoet al[42]spotted a metastatic lateral LLN in a patient with T2 tongue SCC using CT lymphography with peritumoral iopamidol injection, and stressed the possibility that LLNs may serve as sentinel lymph nodes. Sugiyamaet al[43]used CT lymphography in 20 patients with cN0 oral tongue and floor of the mouth cancer. They noticed two LLNs, which were accepted as sentinel lymph nodes, and stated that LLN may be readily identified in 3D with this technique. This suggests that special lymphographic tracing techniques, which are used for sentinel lymph node mapping and biopsy, may be useful in the pre- or intraoperative identification of LLNs[44,45].

Prognosis

Few clinical studies are available in the literature that imply homogenous groups,treatment and/or investigation standardization, long-term follow up, and prognosis calculations. The initial statistical proof that LLN metastases are correlated with worsening of survival prognosis was presented by Hoshinaet al[16]. They observed seven cases of lateral LLN and 3 cases of deep in-transit submandibular node metastases in 43 tongue SCC patients. The associated incidence of delayed regional metastasis development with the presence of LLN lesions was estimated to be 85.7%,with 100% demonstrating a presence of deep submandibular node metastatic involvement. Jiaet al[46]documented a total incidence of LLN metastasis in 17.1% of 111 patients with T0-4, N0 , and N+ tongue cancer. The existence of LLN metastasis was found to be significantly associated with the pathological grade of the tumor. A large clinical study was carried out by Fanget al[47]. They treated 231 patients with T2-4, N0, and N+ tongue SCC, and all subjects underwent an in-continuity operation. The surgical specimen of the floor of the mouth was separated postoperatively, and then histologically examined for the presence of LLNs and LLN metastasis. LLNs were identified in 58 patients (23.1%), with a mean number of 1.3. Of these patients, 33 had metastatic deposits within the LLN, with a total LLN metastasis incidence of 14.3%. It was shown that LLN metastasis was significantly related with the following pathological features: Lymphovascular and peritumoral invasion, tumor stage,presence of regional metastasis, and malignancy grade. The loco-regional control rate was significantly related to the finding of LLN metastasis. For patients who exhibited LLN metastasis, the 5-year loco-regional control rate was estimated to be 45%, while this rate was estimated to be 65% in patients without LLN lesions. According to these new data, LLN metastasis should be considered as an adverse prognostic factor, as well as a strong sign of high primary tumor aggressiveness.

Figure 3 Lymph drainage direction toward the parahyoid LLNs. Parahyoid LLN lies in an in-transit position of the lymph flow (arrows) from the tongue mucous membrane to level II. If present, paraglandular LLN may drain into the parahyoid LLN.

CONCLUSION

While summarizing the available literature on LLNs, it becomes obvious that rates of anatomical existence and metastatic LLN involvement incidence may in not be considered low. Surgical excision implies that adjacent sublingual glands and floor of the mouth subunits are included in the volume of resected tissues. This assures treatment radicality, although it cannot be applied to all tongue cancer patients. As these lesions were shown to significantly influence prognosis, special efforts for their detection must be made. Such measures as pre- or intraoperative palpatory inspection may uncover occult disease in the LLNs. Preoperative contrast-enhanced CT and MRI with postoperative ultrasound follow-up exams are diagnostically beneficial for cN0 patients. Special lymphographic tracing methods as used for sentinel lymph node mapping have the potential to improve LLN identification. In addition, more clinical studies on LLN metastasis diagnosis and treatment must be performed for the possible inclusion of these nodes in the TNM staging system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Alexander Gaprindashvili for the artwork development.

World Journal of Clinical Oncology2020年6期

World Journal of Clinical Oncology2020年6期

- World Journal of Clinical Oncology的其它文章

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma accompanied by pure red cell aplasia: A case report

- Immune response activation following hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal metastases: A pilot study

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines compliance of a sarcoma service: A retrospective review

- Preoperative markers for the prediction of high-risk features in endometrial cancer

- Role of microRNA dysregulation in childhood acute leukemias:Diagnostics, monitoring and therapeutics: A comprehensive review

- Active surveillance in low risk papillary thyroid carcinoma