Insufficient etiological workup of COVID-19-associated acute pancreatitis: A systematic review

Mark Felix Juhasz, Klementina Ocskay, Szabolcs Kiss, Peter Hegyi, Andrea Parniczky

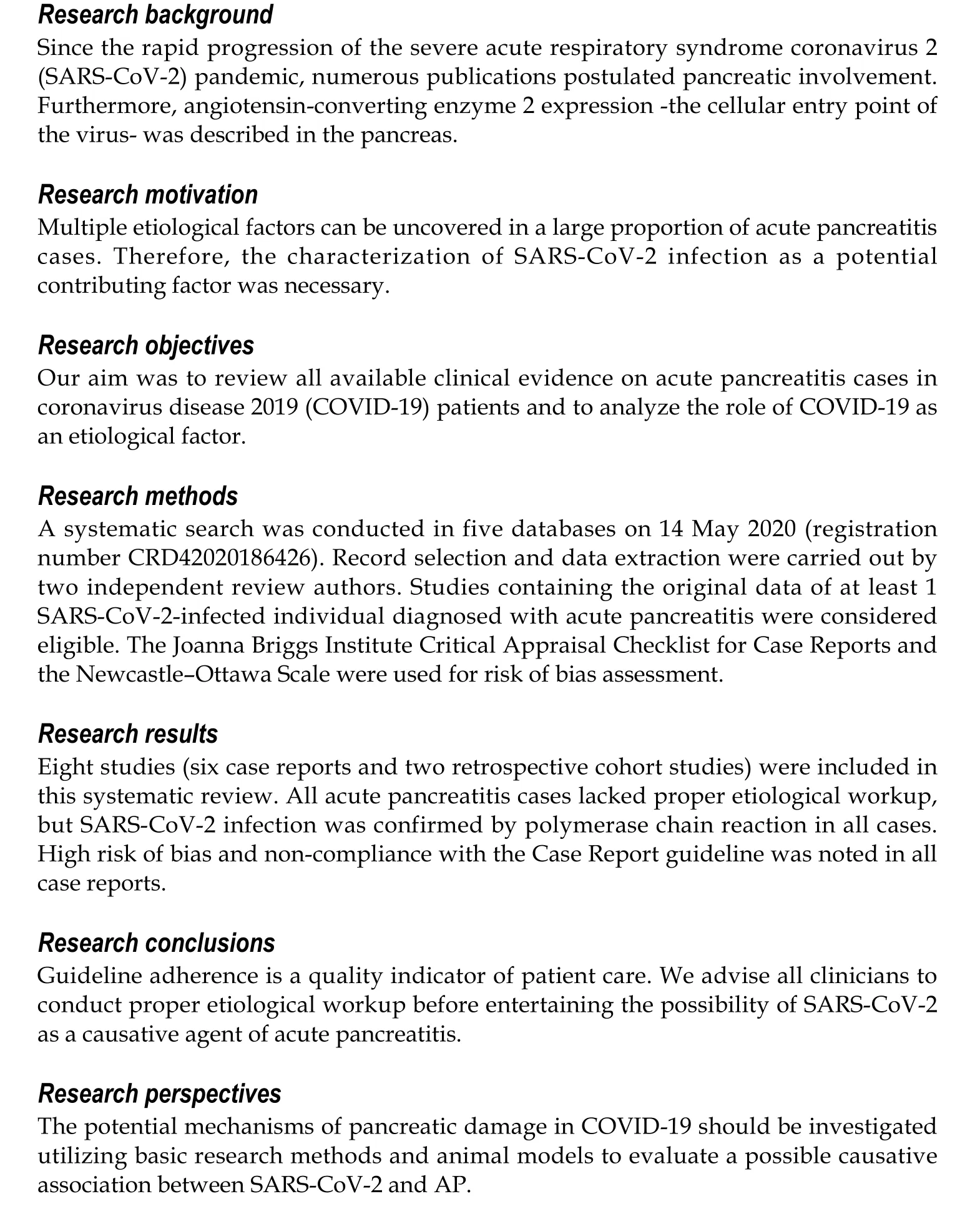

Abstract

Key Words: Pancreas; COVID-19; Pancreatic involvement; Pancreatitis; Amylase; Lipase

INTRODUCTION

In 2019, a novel coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, China, causing multiple cases of severe pneumonia and launching the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. The clinical syndrome seen in SARS-CoV-2 infection is called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The main clinical symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, cough, myalgia, and fatigue[1]. Pulmonary involvement is the most frequent[2], but systemic dissociation is seen in severe cases. Furthermore, a significant proportion of patients exhibit gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. SARS-CoV-2 was also detected in stool specimens[3]and in the cytoplasm of gastric, duodenal, and rectal glandular epithelial cells[4].

Viral infections such as mumps, Coxsackie, hepatitis, and herpes viruses are known causes of pancreatitis[5]. There is a strong possibility that, like other, less common causes of acute pancreatitis (AP), infectious etiology is underdiagnosed on account of the insufficient workup of idiopathic cases and cases where an apparent cause (e.g.,alcohol consumption) is already established[6-8].

On the other hand, during a pandemic of such proportions, polymerase chain reaction testing is made widely available. This will of course lead to a proportion of patients with a variety of diseases, including AP, being diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Given the right temporal association, even a more experienced practitioner could be led to ponder a cause-effect relationship between COVID-19 and AP. Even more so, taking into account the often-neglected etiological workup of idiopathic cases and the opportunity to aid the scientific and medical communities by providing information on presumed complications of the infection.

This systematic review aims to assess all publications containing COVID-19 AP cases and to determine the plausibility of an association between the two.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO as “Pancreas involvement in COVID-19: A systematic review” under registration number CRD42020186426. After completing the systematic search, we decided to deviate from the protocol for the eligibility of studies: We narrowed our focus to AP from the original plan of any pancreatic involvement. We did so because slight pancreatic enzyme elevation in COVID-19 patients, reported by two studies[9,10], has already been discussed by de-Madariaet al[11]and information on pancreatic cancer patients, reported by three studies[12-14]is at this point far too scarce to even discuss its relation with COVID-19 and effect on outcomes. There were no other deviations from the protocol.

Eligibility criteria

Any study, regardless of design, was considered eligible if it contained the original data on at least 1 SARS-CoV-2-infected individual diagnosed with AP. Only human studies were eligible;studies containing solely animal orin vitrodata were excluded.

Systematic search and selection; data extraction

Using the same search key as detailed in the supplementary material (Supplemental 1), the systematic search was conducted in five databases: EMBASE, MEDLINE (viaPubMed), CENTRAL, Web of Science, and Scopus. The last systematic search was carried out on May 14, 2020. The search was restricted to 2020, and no other filters were applied. Citations were exported to a reference management program (EndNote X9, Clarivate Analytics). Two independent review authors (Ocskay K and Juhász MF) conducted the selection by title, abstract and full text based on the previously disclosed, predetermined set of rules. After each selection step, Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ)[15]was calculated. An independent third party (SK) settled any disagreements. Citing articles and references in the studies assessed for eligibility in the full-text phase were reviewed to identify any additional eligible records. Data were extracted from all eligible studies into a standardized Excel sheet designed on the basis of recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration[16](for details on data extraction, see Supplemental 2).

Risk of bias assessment and determination of the quality of evidence

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports[17]was used to assess the risk of bias in case reports, and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale[18]was used for cohorts (results in Supplemental 3). Due to the design and quality of the included studies, the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations approach was not used and a very low grade of evidence was automatically established.

Statistical analysis

Only qualitative synthesis was performed; no statistical analysis was carried out.

RESULTS

Systematic search and selection

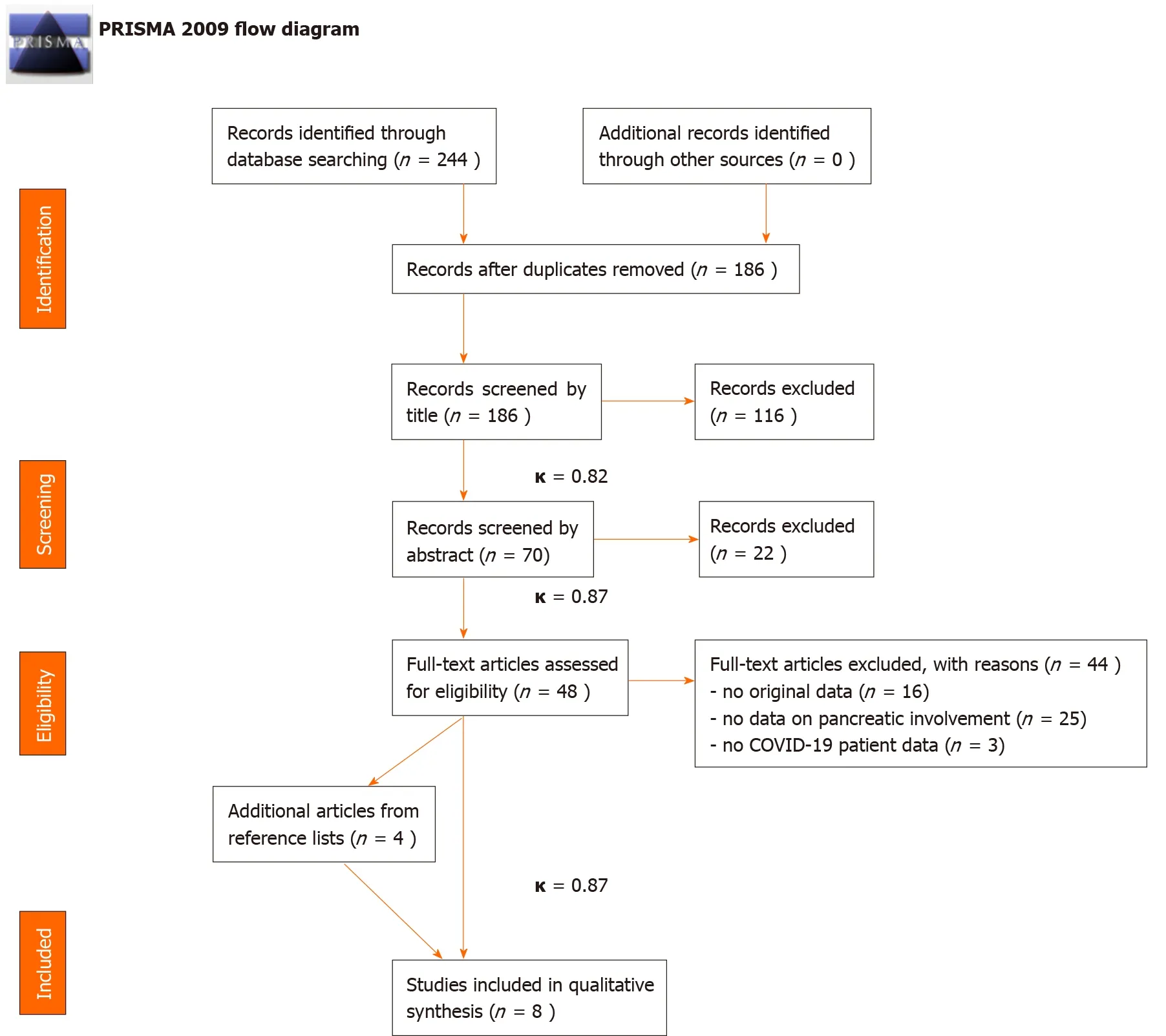

The details of the systematic search and selection are presented in Figure 1.

Characteristics of included studies

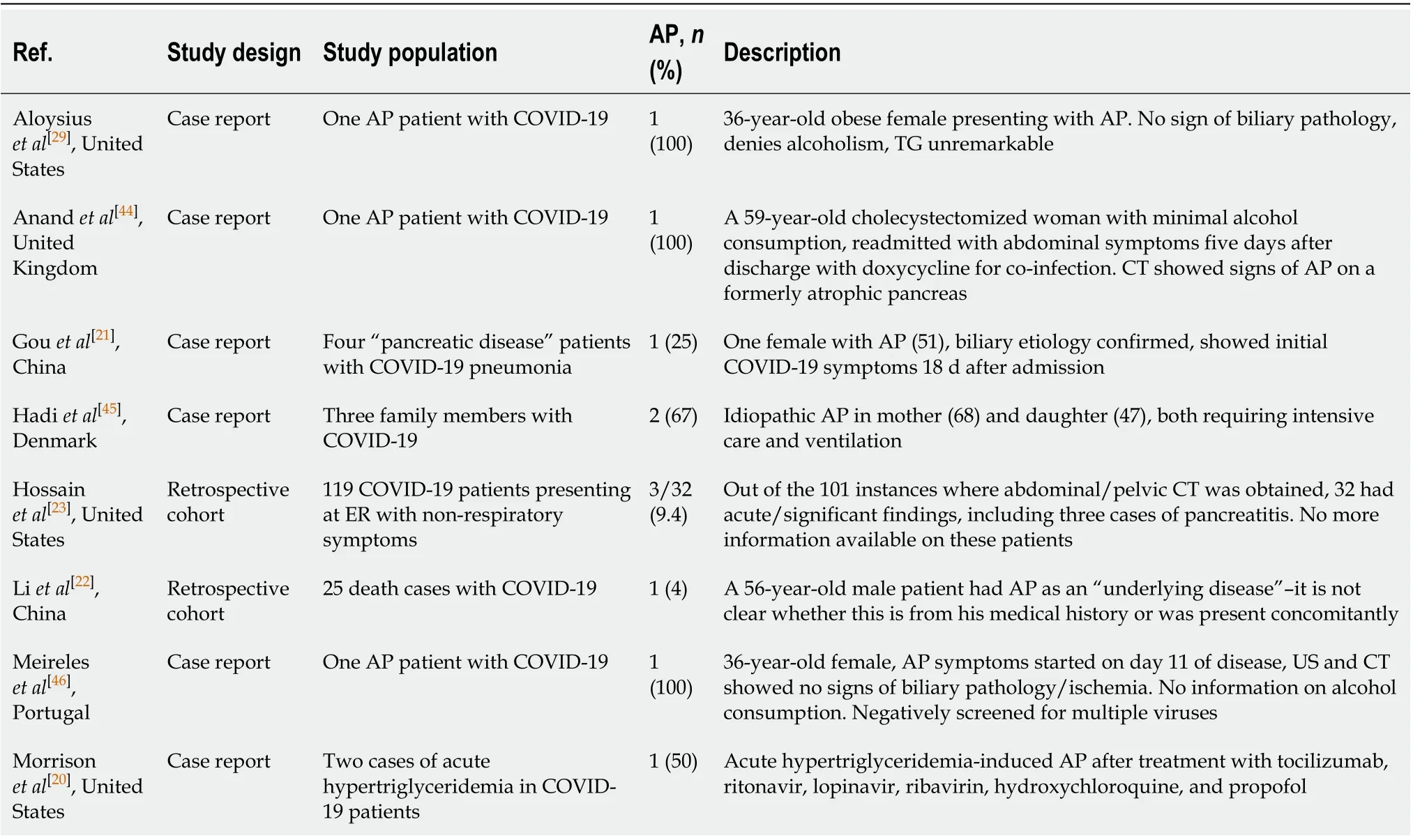

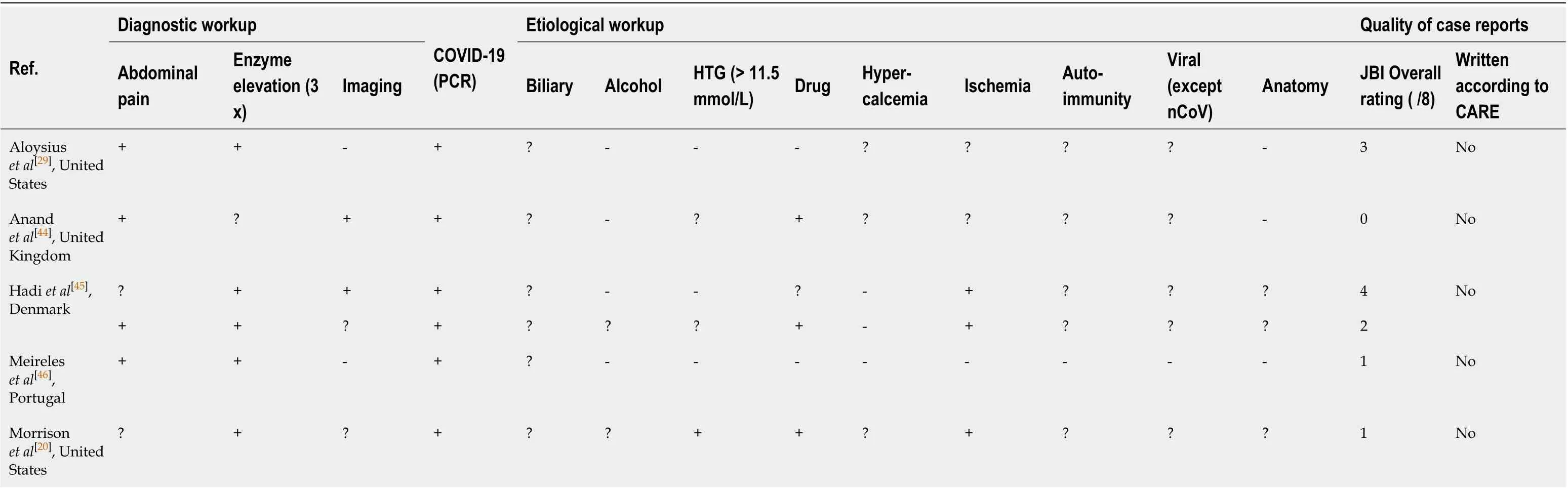

In total, six case reports and two retrospective cohort studies were included in this systematic review (Table 1). Information on the diagnostic criteria and etiological factors of AP was collected from the appropriate case reports in Table 2. Of the six cases, five fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis[19], and in one case[20]enzyme elevation reached the threshold. However, abdominal pain could not be reported on account of the patient being ventilated and sedated, and no imaging findings were disclosed. A case report by Gouet al[21]was not included in this table, as biliary etiology was determined and COVID-19 symptoms first emerged on day 18 of the patient’s hospital stay; thus, the infection was not assumed as an etiological factor[21].

In a retrospective cohort of COVID-19 mortality cases by Liet al[22], AP is listed as an underlying disease in a single patient without further clarification as to whether it is apast event from the patient’s medical history or it occurred during COVID-19-related hospitalization[22]. Hossainet al[23]noted three cases of AP among 119 patients presenting to the ER with non-respiratory symptoms who turned out to have concomitant SARS-CoV-2 infection[23].

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

DISCUSSION

The multiple-hit theory can be implemented in the pathogenesis of AP[24]; therefore, information on possible contributing factors was collected for each case (Table 2). Multiple etiological factors are often responsible for AP[24], but the lack of proper workup often leads to cases being deemed idiopathic or an important factor not being discovered due to the presence of a more convenient diagnosis[6]. In addition to the established etiological factors, various mechanisms have been postulated as the cause of pancreatic damage in COVID-19.

SARS-CoV-2 enters epithelia through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2[25], which is abundantly expressed in the pancreas[26,27]. SARS-CoV-2 RNA and protein were also shown byin situhybridization and immunohistochemistry from autopsy samples of infected patients’ pancreas[28]. Aloysius proposed that virus replication may have a direct cytopathic effect or elicit pancreatic cell death as a consequence of the immune response[29]. Furthermore, microvascular injury and thrombosis have been described as a consequence of COVID-19[30,31], which, complicated with shock and gastrointestinal hypoperfusion[32], could also cause pancreatic damage[33].

However, a cause-effect relationship has not been investigated directly so far. Also, before entertaining the possibility of a new virus as a causative agent in cases where no apparent etiological factors are present, other, less frequent causes of AP must be considered. In such cases, the International Association of Pancreatology/American Pancreatic Association (IAP/APA) recommendations should be followed[6,7,19].

For instance, drugs used in treating COVID-19 may cause pancreatic damage directly or indirectly. A patient whose case was presented as idiopathic AP was on a course of doxycycline, which is a drug with a documented probable association with pancreatitis[34]. Several drugs currently used or being considered for COVID-19 might play a role in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis, such as enalapril, asparaginase,estrogens, and steroids[34]. Hypertriglyceridemia, another established etiological factor frequently neglected, can also occur as a consequence of therapy, as in the case described by Morrisonet al[20]. Not only tocilizumab[35]but propofol and ritonavir could also have been responsible for the elevation of serum triglyceride levels in this case[36]. Hypertriglyceridemia-associated drug-induced AP was observed[37,38]in association with the following drugs being tested for COVID-19 according to our search on clinicaltrials.gov: lisinopril, asparaginase, estrogens, isotretinoin, steroids, propofol, and ruxolitinib.

Table 2 Diagnostic and etiological workup and quality assessment of the studies

In a case reported by Aloysiuset al[29], there are no apparent etiological factors present in the description. Even so, the report does not describe any further efforts to identify the seemingly idiopathic etiology, such as performing an endoscopic ultrasonogram. While thoroughly ruled out AP-associated viruses and even screened for antinuclear antibodies, they also did not utilize endoscopic ultrasonogram during the etiology search.

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram demonstrating the selection of studies to be included in the review. κ represents Cohen’s Kappa values indicating the rate of agreement between selection coordinators. COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

Other than the highlighted problems tied to the etiological workup, we would like to briefly address an issue with the diagnosis. Two studies not included in this review[9,10]labeled patients with serum amylase and/or lipase values higher than the upper limit of normal to possess “pancreatic injury”. As de-Madariaet al[11]pointed out in reflecting on Wanget al[9], the elevation of pancreatic enzyme levels in the blood is not necessarily a consequence of an insult to the pancreas. Possible reasons are the high prevalence of renal impairment and diabetes mellitus, gastroenteritis, and metabolic changes, such as acidosis, or even salivary glandular entry by SARS CoV-2[39-42]. More importantly, a slight elevation in serum amylase and/or lipase levels alone is not established as an indicator of pancreatic damage. The Atlanta diagnostic criteria should be applied when determining the presence of AP[19].

The case reports in our review carry considerable risk of bias and their deviation from the Case Report guideline[43]on reporting methods. As demonstrated, the etiological workup of patients was incomplete, and often COVID-19 was named as the causative agent of AP, while other established factors were also present.

Considering limitations, incomplete reporting of the included studies encompasses a high risk of bias in our analysis[44-46].

CONCLUSION

To conclude, we strongly emphasize the need for guideline adherence when diagnosing and uncovering the underlying etiological factors of AP, even during a pandemic. As specific therapeutic options[19]are available depending on etiology, neglecting these steps can hinder direct therapy and lower the chances of recovery, while increasing the probability of complications and recurrent episodes.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年40期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年40期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Cirrhotic portal hypertension: From pathophysiology to novel therapeutics

- New strain of Pediococcus pentosaceus alleviates ethanol-induced liver injury by modulating the gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid metabolism

- Prediction of clinically actionable genetic alterations from colorectal cancer histopathology images using deep learning

- Compromised therapeutic value of pediatric liver transplantation in ethylmalonic encephalopathy: A case report

- Predicting cholecystocholedochal fistulas in patients with Mirizzi syndrome undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- Novel endoscopic papillectomy for reducing postoperative adverse events (with videos)