Imaging-based algorithmic approach to gallbladder wall thickening

Pankaj Gupta, Yashi Marodia, Akash Bansal, Naveen Kalra, Praveen Kumar-M, Vishal Sharma, Usha Dutta,Manavjit Singh Sandhu

Abstract Gallbladder (GB) wall thickening is a frequent finding caused by a spectrum of conditions. It is observed in many extracholecystic as well as intrinsic GB conditions. GB wall thickening can either be diffuse or focal. Diffuse wall thickening is a secondary occurrence in both extrinsic and intrinsic pathologies of GB, whereas, focal wall thickening is mostly associated with intrinsic GB pathologies. In the absence of specific clinical features, accurate etiological diagnosis can be challenging. The survival rate in GB carcinoma (GBC) can be improved if it is diagnosed at an early stage, especially when the tumor is confined to the wall. The pattern of wall thickening in GBC is often confused with benign diseases, especially chronic cholecystitis, xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis, and adenomyomatosis. Early recognition and differentiation of these conditions can improve the prognosis. In this minireview, the authors describe the patterns of abnormalities on various imaging modalities (conventional as well as advanced) for the diagnosis of GB wall thickening. This paper also illustrates an algorithmic approach for the etiological diagnosis of GB wall thickening and suggests a formatted reporting for GB wall abnormalities.

Key Words: Gallbladder diseases; Cholecystitis; Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses of the gallbladder; Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis; Neoplasms; Acute cholecystitis

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder (GB) wall normally appears as a pencil-thin line[1,2]. Most studies suggest a wall thickness of 3 mm as the upper limit of normal thickening[3,4]. In a retrospective review of 4119 patients, it was found that the GB wall in normal subjects measured 2.6 ± 1.6 mm[5]. The thickened GB wall frequently seen in diagnostic imaging is mostly attributed to intrinsic GB pathologies. However, as GB wall thickening is a nonspecific finding, it frequently leads to diagnostic dilemmas, especially in asymptomatic individuals. Diffuse GB wall thickening can be seen in extracholecystic conditions and misinterpretation in such cases can lead to unnecessary cholecystectomy[6]. Besides, both focal and diffuse GB wall thickening can be seen in benign and malignant lesions. An accurate radiological characterization of the causes of wall thickening is of utmost importance for instituting appropriate management. Studies have suggested certain imaging features that help differentiate benign from malignant GB wall thickening. Despite this, many cases are still reported as equivocal on preoperative imaging. This is partly due to a lack of awareness among radiologists and physicians regarding the different imaging criteria for differential diagnosis.

CAUSES OF GB WALL THICKENING

GB wall thickening can be classified into diffused and focal[2]. Diffuse wall thickening can be due to either intrinsic or extrinsic causes. The most important causes of diffuse thickening include acute and chronic cholecystitis, adenomyomatosis (ADM), xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC), and wall thickening type of GB carcinoma (GBC)[1]. Systemic diseases that lead to diffuse thickening include hepatitis, congestive heart failure, renal failure, sepsis, and hypoalbuminemia. Other causes are the spread of inflammation from adjacent organs as in the cases of pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, colitis, and peritonitis[1,3,7]. Immunoglobulin G 4 related sclerosing cholecystitis is a rare cause of diffuse GB wall thickening[8]. Focal wall thickening most commonly occurs due to the intrinsic causes. The malignant causes include GBC, GB lymphoma, and metastasis (most commonly from melanoma), while the most common benign causes include focal XGC, focal ADM, and localized chronic cholecystitis[9].

THE ROLE OF IMAGING MODALITIES IN DIFFERENTIATING BENIGN AND MALIGNANT GB WALL THICKENING

Ultrasonography (USG) is the initial imaging test of choice for the evaluation of suspected GB pathology[10]. USG is widely available, has a low cost, and the advantage of real-time assessment. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are utilized for cases with inconclusive findings on USG, the staging of GBC, and suspected complications in acute inflammatory GB conditions. Endoscopic ultrasound is an advanced technique with the advantage of the proximity of the probe to the GB wall leading to higher resolution, and providing safe access for tissue sampling. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) and shear wave elastography (SWE) are useful adjuncts to USG for assessment of the GB wall.

USG

USG allows direct visualization of the GB wall due to its superficial location. It is an accurate modality for the measurement of the GB wall thickness[10]. A normal GB wall on USG appears as a thin echogenic rim ≤ 3 mm. GB USG examination should always be done in a fasting state, as pseudo-thickening seen in contracted GB (consisting of a double concentric hyperechoic layer with sonolucency in-between) can also be observed in some pathological conditions[11].

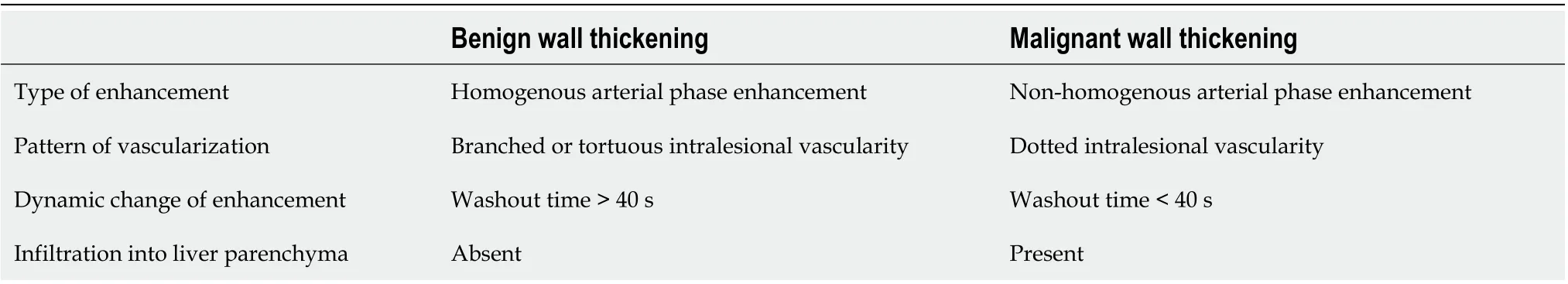

There are some specific features on USG which must be recognized to distinguish between benign and malignant causes of GB wall thickening (Table 1). Asymmetric and irregular wall thickening is typical of GBC. However, in the early stages, the thickening can be smooth and can be misdiagnosed as benign wall thickening. Echolayering of GB wall (defined as alternate hypoechoic and hyperechoic layers) with a distinct specular mucosal lining favors a benign etiology (Figure 1A). The discontinuity of the mucosal echo is more commonly seen in patients withGBC(Figure 1B)[12]. This striated wall thickening of GB was earlier considered to be a specific sign of acute cholecystitis but can occur in a variety of conditions, such as renal failure, heart failure, acute hepatitis, ascites, acute pancreatitis, and prominent Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses[13]. A mesh-like wall thickening has been considered a distinctive feature of GB edema due to extracholecystic causes and helps differentiate these conditions from acute cholecystitis, which may prevent unnecessary cholecystectomy (Figure 1C)[6]. Teefeyet al[13]suggested that striations in the thickened wall in acute cholecystitis suggest gangrenous changes. However, greyscale USG has its limitations as it only demonstrates the morphological changes in the GB wall. The use of color Doppler helps in assessing vascularity and improving diagnostic accuracy[14-17]. Studies have shown that the malignant causes of GB wall thickening show a higher peak systolic velocity than benign conditions[14-16]. Sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 96%, respectively, have been reported by Hayakawa Set al[16]at a cut off value of 30 cm/s for flow velocity. A few studies have highlighted the synergistic role of SWE for differentiating benign from malignant wall thickening[17-19]. In the study by Kapoor Aet al[17], SWE was reported to have a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 91.3% respectively, for distinguishing benign from malignant GB wall thickening. The cut-off value of 2.7 m/s was proposed for this differentiation. High shear wave velocity favors malignancy. SWE has been shown to improve the diagnostic accuracy of USG for the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis[20]. SWE has also been shown to increase the sensitivity and specificity of grading of acute cholecystitis into moderate and severe[21].

CEUS

CEUS has an established role in the evaluation of lesions in the liver and kidney. It is now increasingly recognized as a useful tool for the characterization of GB lesions. A normal GB on CEUS has a uniformly enhancing wall without discontinuity and an anechoic lumen[20]. Two phases of enhancement are observed after a micro-bubble injection: An arterial phase at 10-20 s and a late phase at 30-180 s[21].

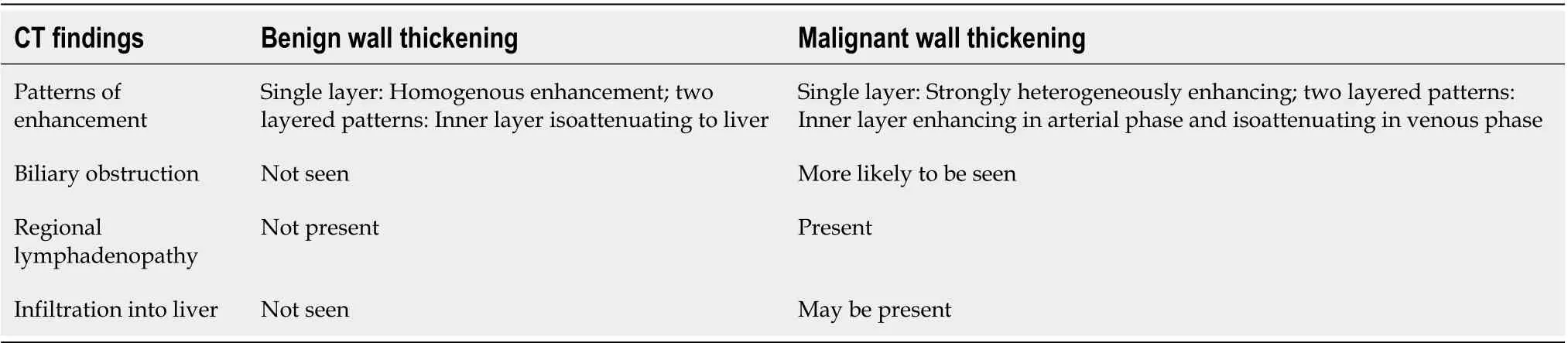

CEUS significantly improves the diagnostic accuracy of USG in differentiating benign and malignant GB lesions especially for the wall thickening type lesions (Table 2)[22]. Studies have shown the better diagnostic performance of CEUS as compared to MRI for differentiating malignant and benign lesions[23]. Various characteristics including enhancement time, extent and dynamicity of enhancement, the pattern of vascularity, intactness of GB wall, degree of thickness, and infiltration into adjacent liver parenchyma should be assessed. Benign diseases show symmetrical wall thickening, preserved layered appearance, washout time of > 40 s, and dotted linear vascularity. Features such as arterial phase irregular intralesional vascularity,late phase hypoenhancement, disruption ofGB wall and infiltration into the adjacent liver are highly predictive of malignant lesions (Figure 2)[24,25]. A specificity of 92.4% for detection of malignant GB wall thickening was shown in a study when two out of the following three features were present: An irregular shape, branched intralesional vessels, and hypo-enhancement in the late phase[26]. The most important predictor of malignancy is an inhomogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase, followed by interrupted inner layer, early washout (≤ 40 s), and wall thickness > 1.6 cm[27].

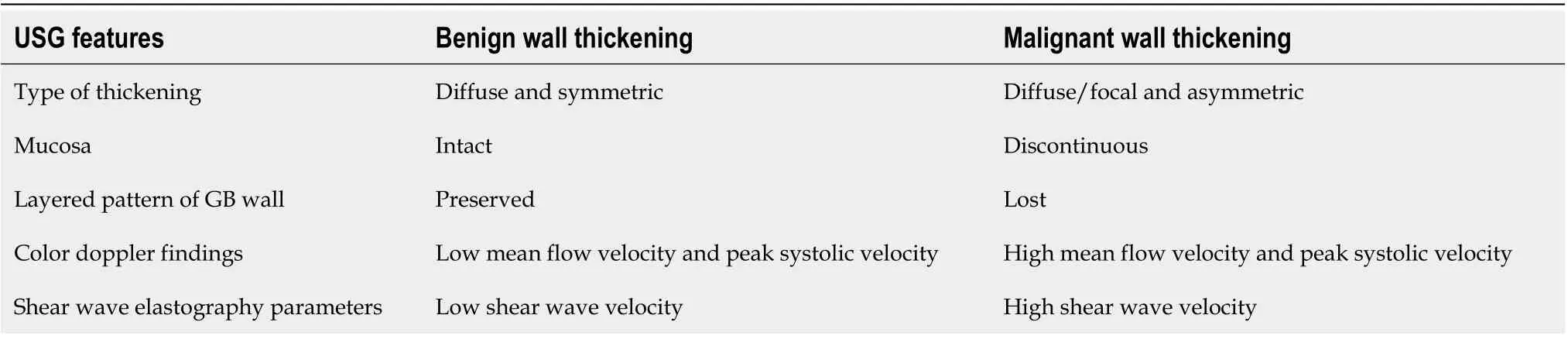

Table 1 Features of ultrasonography which help in differentiation of benign and malignant gallbladder wall thickening

Table 2 Features of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography which help in differentiation of benign and malignant gallbladder wall thickening

Figure 1 Ultrasound features of benign and malignant gallbladder wall thickening. A: Mild symmetrical mural thickening with clearly defined layers (arrow) suggestive of benign thickening; B: Asymmetrical mural thickening with foal discontinuity of mucosa (arrow) suggestive of malignant thickening; C: Marked circumferential mural thickening with mesh like architecture (arrow) is seen. Also note the nodular outline of liver (short arrow) and ascites (white arrow) suggestive of decompensated ascites as the underlying cause.

CT

Currently, the widespread use of abdominal CT has led to the increased detection of conditions associated with GB wall thickening[28]. A normal GB wall on contrastenhanced CT usually appears as a thin enhancing rim of soft tissue density. A mural thickening of up to 3 mm is considered normal[28]. However, the thickness depends upon the degree of GB distension.

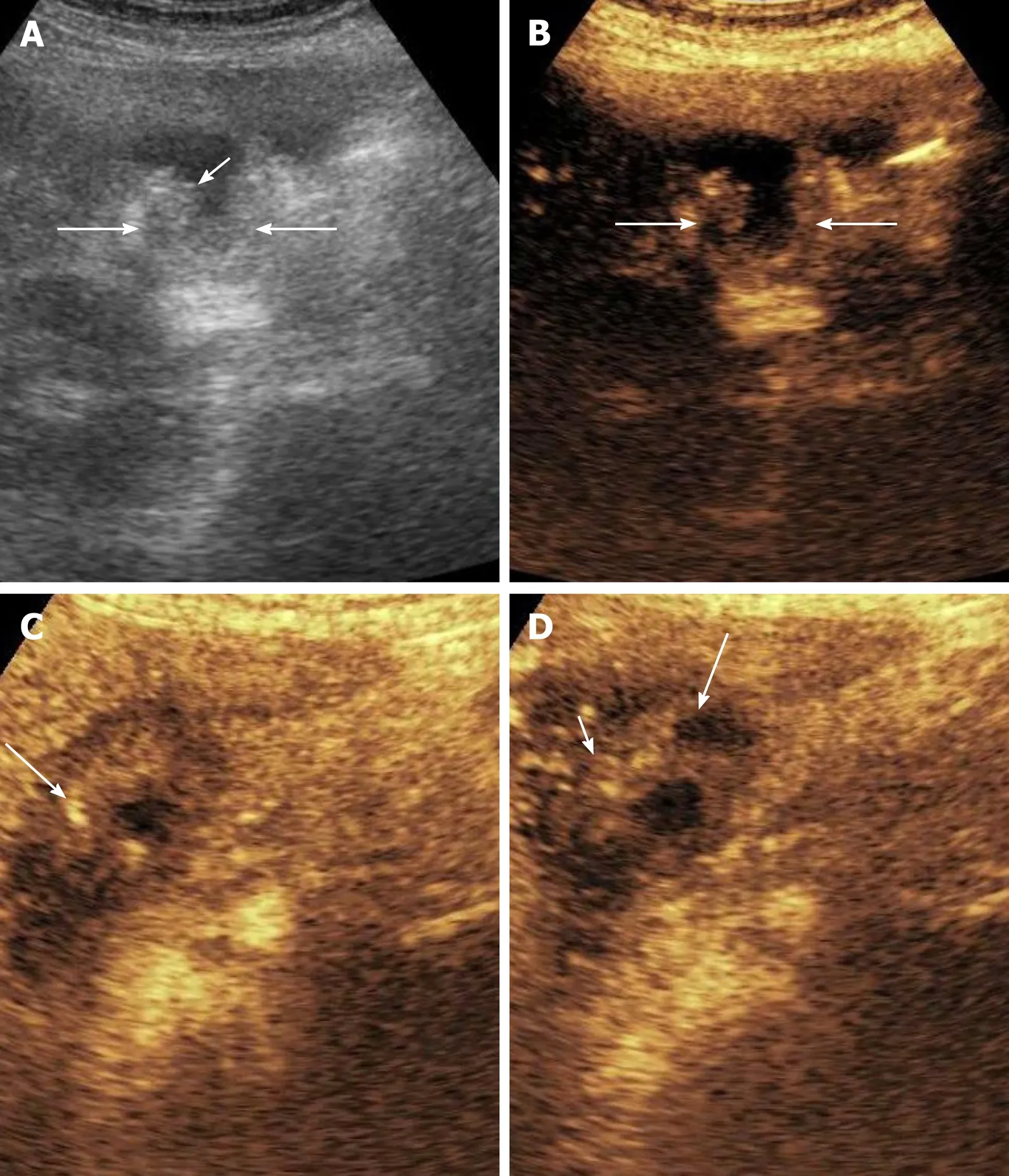

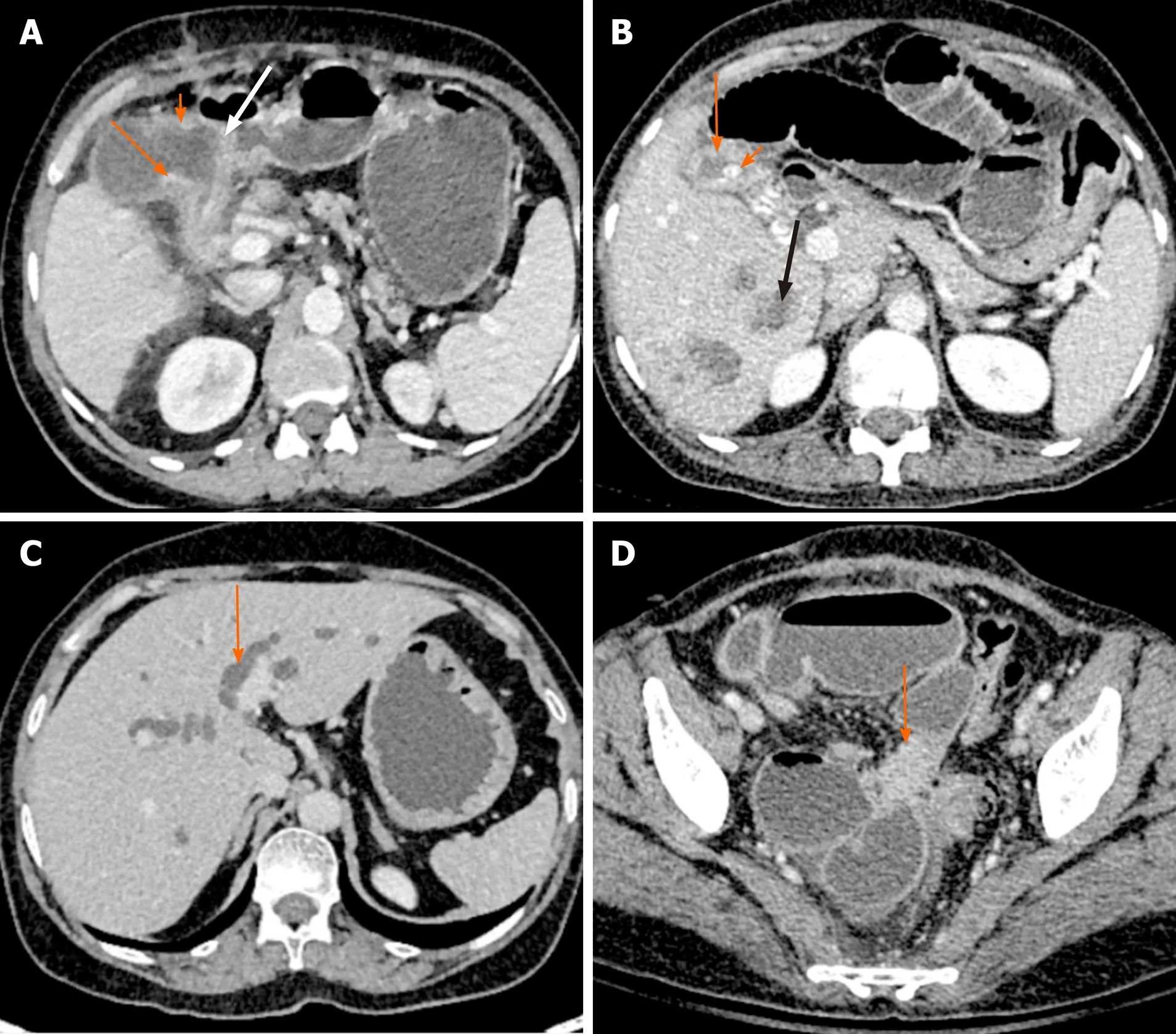

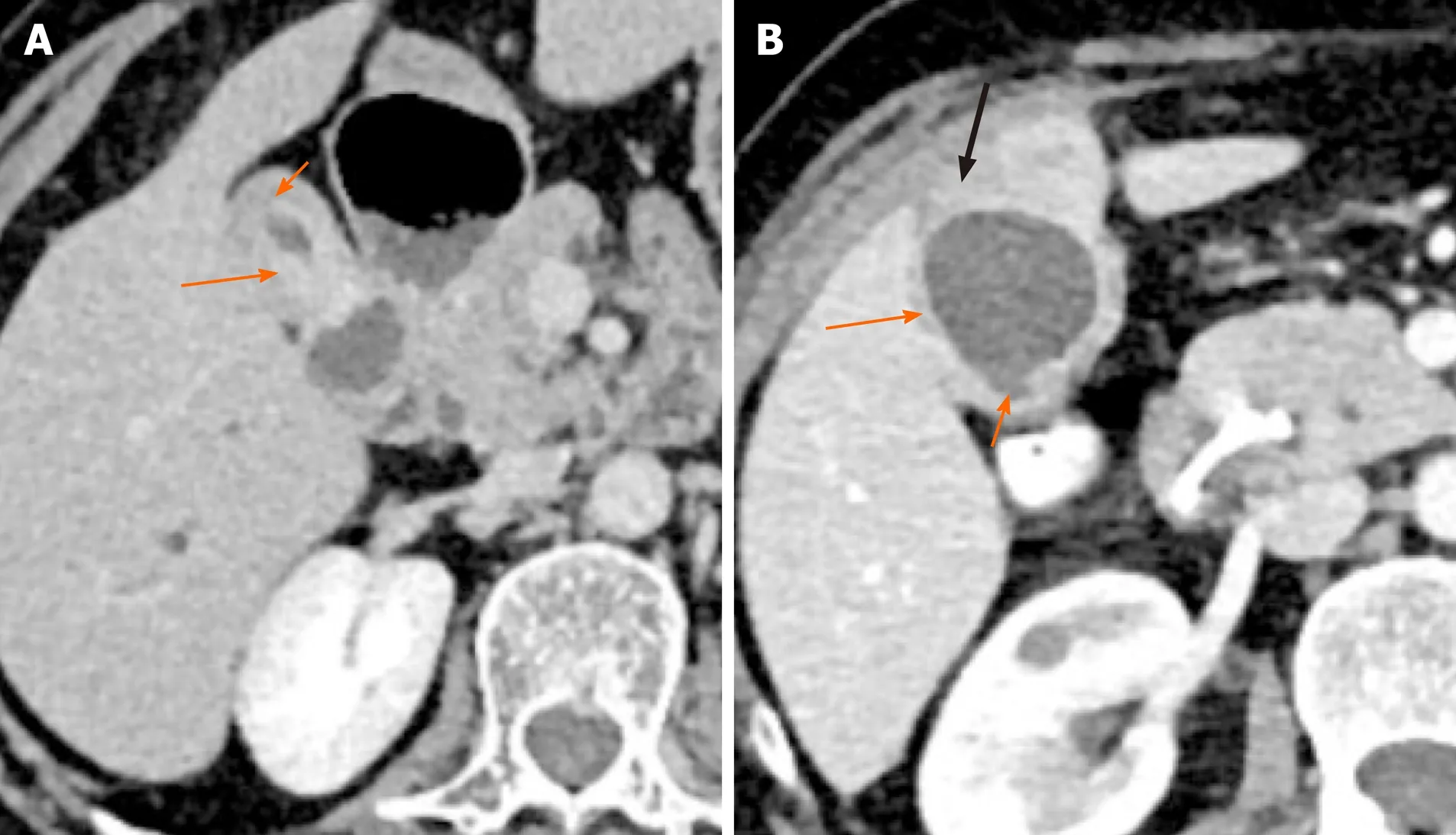

There are a few direct and indirect findings that help in differentiating benign and malignant GB wall thickening (Table 3). Irregularity in the wall, focalwall thickening, discontinuous mucosa, submucosal edema, polypoidal mass, and direct invasion into an adjacent organ are the direct findings observed in malignant lesions (Figure 3A).The indirect signs predictive of malignancy include biliary obstruction, regional lymphadenopathy, paraaortic lymphadenopathy, and distant metastasis (Figure 3BD). However, CT has limited sensitivity for the detection of metastases to lymph nodes < 10 mm[29]. Also, regional lymphadenopathy has been reported in 62.5% of cases with XGC. This overlapping feature can be a limitation in diagnosis on CT[30]. Various studies have reported the enhancement patterns to distinguish benign from malignant wall thickening. Kimet al[31]has suggested five patterns of GB wall enhancement in diffuse wall thickening. The two-layer pattern with strong enhancement of the thick inner layer (≥ 2.6 mm) and a weak enhancing of the outer layer (≤ 3.4 mm), and the one-layer pattern with a heterogeneous and thick enhancing wall, were significantly associated with GBC (Figure 4). Corwinet al[32]studied the enhancement pattern in cases of focal fundal wall thickening. They proposed six morphological patterns of thickening. Malignant cases were identified most in Type 6 (heterogeneous enhancement of the focal fundal wall thickening without discrete cystic spaces). A few cases of malignancy were also seen in Type 3 (enhancement of the entire focal fundal thickening).

Table 3 Features of computed tomography which help in differentiation of benign and malignant gallbladder wall thickening

Figure 2 Contrast enhanced ultrasound in gallbladder wall thickening. A: Grey scale image shows asymmetrical mural thickening in the neck and body of gallbladder (arrows), short arrow shows the lumen of gallbladder; B: Image before contrast injection shows the baseline status of the gallbladder (arrows show the wall); C: Image at 17 s after contrast injection shows heterogenous mural enhancement (arrow); D: Image at 35 s shows washout (arrow). The infiltration of adjacent liver (short arrow) is well visualized on this image.

Figure 3 Direct and indirect findings of malignant gallbladder wall thickening on computed tomography. A: There is asymmetrical mural thickening of the gallbladder neck (arrow). Also note the nodularity of the gallbladder wall in the body (short arrow) and loss of fat plane with the antropyloric region of stomach (white arrow); B: Gallbladder wall is thickened and heterogeneous (arrow). There is a calculus at the neck (short arrow). Multiple hypodense lesions are seen in right lobe (black arrow). Fine needle aspiration cytology from one of these lesions revealed metastasis; C: There is bilobar intrahepatic biliary radicle dilatation in a patient with gallbladder cancer (arrow); D: A soft tissue deposit is seen in subserosal location in pelvis causing bowel obstruction (arrow).

Figure 4 Patterns of malignant gallbladder wall thickening on computed tomography. A: There is thick enhancing inner layer (arrow) and relatively hypoenhancing outer layer (short arrow); B: There is heterogeneously enhancing gallbladder wall (arrow) with focal disruption of mucosa (short arrow) and serosa (black arrow) at certain places.

MRI

MRI is used in the evaluation of GB pathologies to resolve diagnostic dilemmas because of its superior soft tissue delineation. A normal GB wall is hypointense on T2-weighted images, isointense on T1-weighted images and shows homogenous postcontrast enhancement. The bile within GB is hyperintense on T2-weighted images and shows variable signal intensity on T1-weighted images depending on the bile concentration[33].

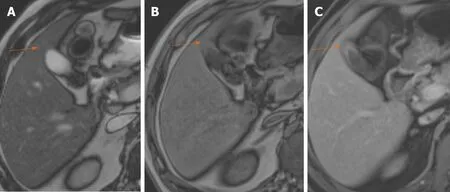

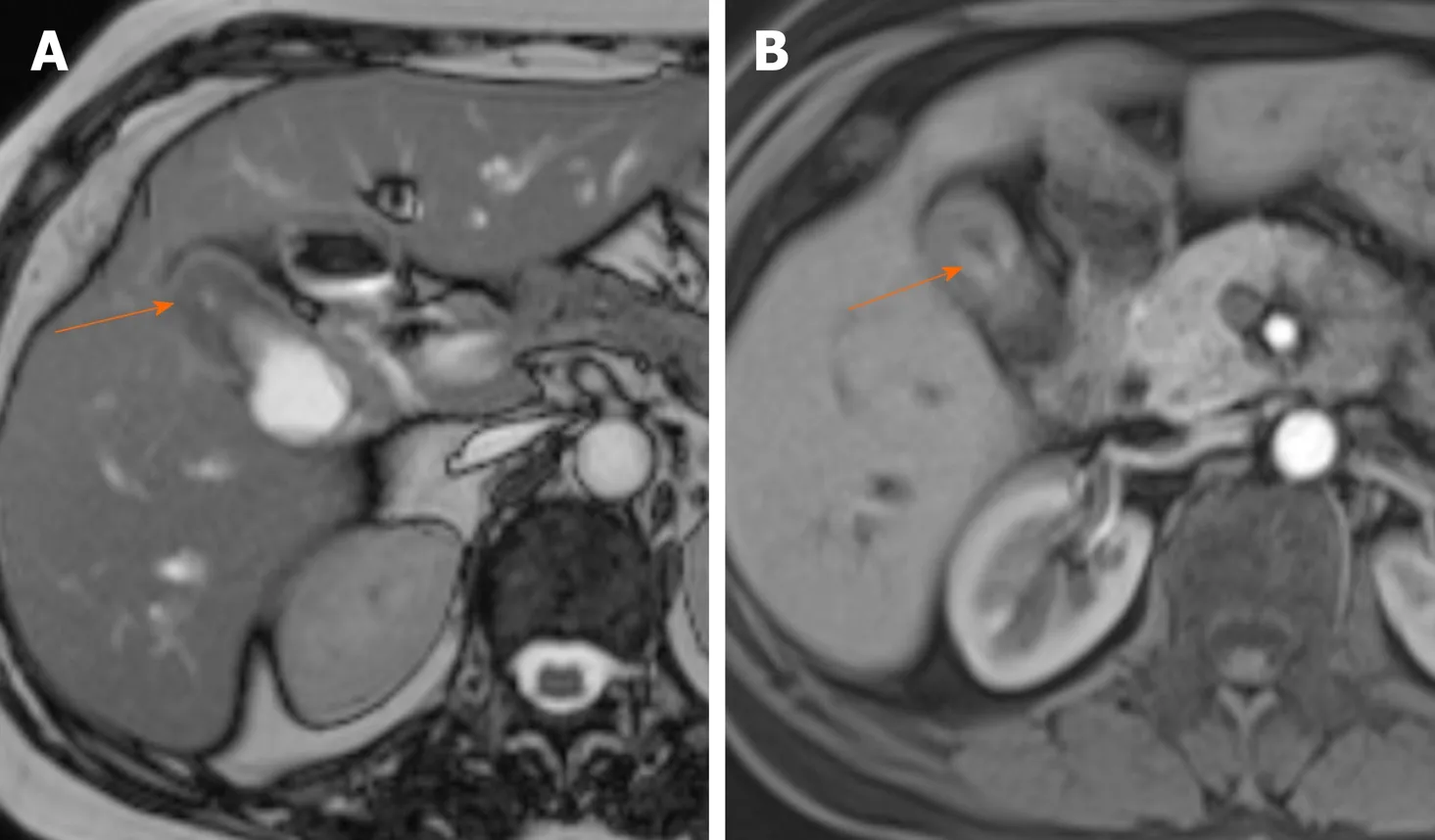

On non-contrast MRI, benign GB wall thickening usually shows T1-weighted and T2-weighted hyperintensity (Figure 5). Malignant thickening shows moderate T2 hyperintensity with papillary appearance and diffusion restriction[34]. On dynamic contrast enhanced MRI, benign wall thickening shows relatively slow enhancement, whereas malignant wall thickening demonstrates early enhancement (Figure 6). The early enhancement seen in malignant lesions is due to neovascularization. No significant difference in enhancement in the delayed phase is observed, probably due to an equal amount of fibrous interstitium in benign and malignant wall thickening[35]. The MRI features to differentiate between benign and malignant GB wall thickening are presented in Table 4. Attempts have been made to differentiate benign and malignant wall thickening on the basis of classification of wall thickening into 4 patterns, as described by Junget al[36]on heavily T2 weighted images (half–Fourier acquisition single short turbo spin echo). Type 1 shows a thin hypointense inner layer and a thick hyperintense outer layer which corresponds to the pathological diagnosis of chronic cholecystitis. Type 2 consists of two layers of ill-defined margins, suggestive of acute cholecystitis. Type 3 shows multiple hyperintense cystic spaces in the wall, correlating with the pathological diagnosis of ADM. While type 4 shows diffuse nodularthickening without layering, seen mostly in malignant cases. Several studies have reported the usefulness of diffusion-weighted images (DWI) for the differentiation of malignant and benign GB wall thickening. Kitazumeet al[37]suggested an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value of less than 1.2 × 10-3mm2/s or lesion to spinal cord ratio of more than 0.48 in malignant thickening. When this cutoff value was combined with morphological patterns such as massive thickening, disrupted mucosal line, and absence of a two-layered pattern, sensitivity, and specificity of 73.0% and 96.2% respectively was reported. Solaket al[38]reported that ADC value below 0.86 × 10-3mm2/s is significantly associated with malignancy. A mean ADC value of 1.83 ± 0.69 × 10-3mm2/s and 2.60 ± 0.54 × 10-3mm2/s has been reported in malignant and benign GB pathology respectively by Ogawaet al[39]. DWI should always be interpreted along with the findings of other MRI sequences.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-CT

Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-CT (FDG-PET) has better sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between benign and malignant tumors as compared to other diagnostic modalities[40,41]. FDG uptake in GB can be due to both inflammatory and malignant conditions. PET-CT in the evaluation of GB wall thickening is indicated when there is any diagnostic dilemma on conventional imaging such as USG, CT, or MRI[42,43]. The thickness of the GB wall and standardized uptake value (SUVmax) has a complementary role in addition to visual analysis for the differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. Benign conditions show less SUVmaxvalue than malignant lesions. Diagnostic accuracy of 95.9% was reported by Fontet al[44]when a cut off value of 3.62 was used. Guptaet al[45]reported a sensitivity and specificity of 92% and 79%, respectively at a cutoff value of SUVmaxof 5.95. Using a cut off value of mean GB wall thickening 8.5 mm, sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 67%, respectively was reported. In addition to differentiating between benign and malignant conditions, PET-CT helps in the staging of malignant lesions.

DIFFERENTIATION OF SPECIFIC ENTITIES

GBC vs ADM

The focal as well as the diffuse GB wall thickening can be seen in both GBC and ADM. A preoperative diagnosis is required to avoid unnecessary cholecystectomies in asymptomatic patients with ADM.

Diffuse ADM shows symmetricalmural thickening, intramural cystic spaces, and echogenic foci (causing twinkling artefacts on USG). Irregularmural thickening of the outerlayer, irregularity or focal discontinuity of innermost hyperechoic layer (thickness > 1 mm), loss of multilayer pattern, and intralesional vascularity are significantly associated with GBC[46]. The comet-tail artefact was earlier considered to be specific to ADM. This artefact is caused by the accumulation of cholesterol crystals in the Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses and can also be seen in the other benign conditionsof GB. Studies have shown comet tail artefact to be a reliable sign of benignity of the lesion[47]. Certain MRI features help to differentiate ADM from GBC. The pearl necklace sign, defined as linear hyperintense foci on T2-weighted images, has been described as a specific sign, especially for diffuse ADM (Figure 7)[48]. However, T2 hyperintense foci can also be seen in well-differentiated mucin-producing GBC. The size, shape, number, and arrangement of the cystic components may help in the differential diagnosis. The cystic component in ADM is smaller, rounded, arranged in a linear fashion, and the wall shows a flat contour with a regular surface[49]. Welldifferentiated GBC shows larger, multilobulated cystic components and the wall shows an irregular surface contour. On CEUS, ADM shows arterial phase heterogeneous enhancement with small non-enhancing spaces within. The mucosal and serosal layers of the GB wall surrounding the lesions are enhanced and can be observed as two hyperechoic lines in the arterial phase. The smaller non-enhancing spaces are more clearly seen during the venous phase[50].

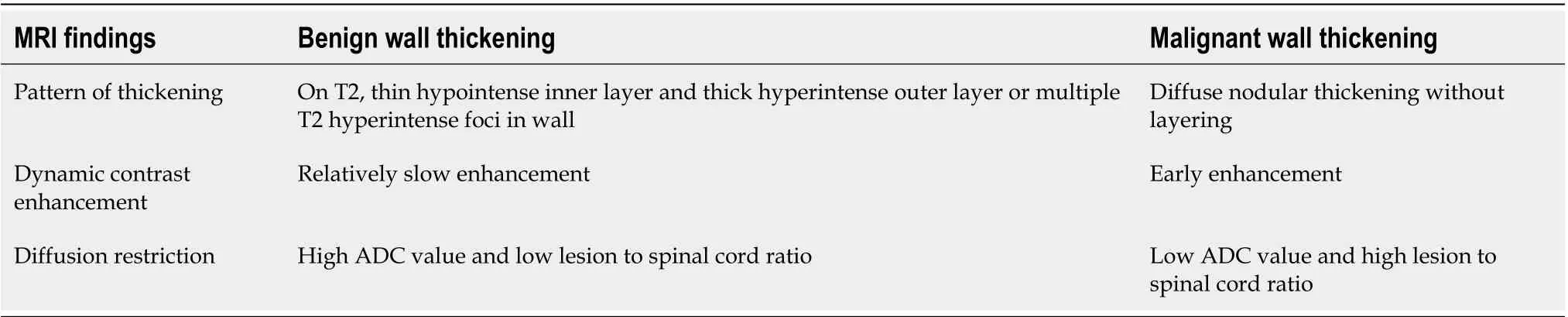

Table 4 Features of magnetic resonance imaging which help in differentiation of benign and malignant gallbladder wall thickening

Figure 5 Benign gallbladder wall thickening on magnetic resonance imaging. A: T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging shows hypointense thickening of the gallbladder fundus (arrow); B: The thickening shows subtle hyperintensity on T1-weighted image (arrow); C: There is homogeneous contrast enhancement on gadolinium enhanced image (arrow).

Figure 6 Malignant gallbladder wall thickening on magnetic resonance image. A: True fast imaging with steady state precession image shows marked thickening of the gallbladder fundus (arrow); B: Arterial phase of contrast enhancement shows early enhancement (arrow).

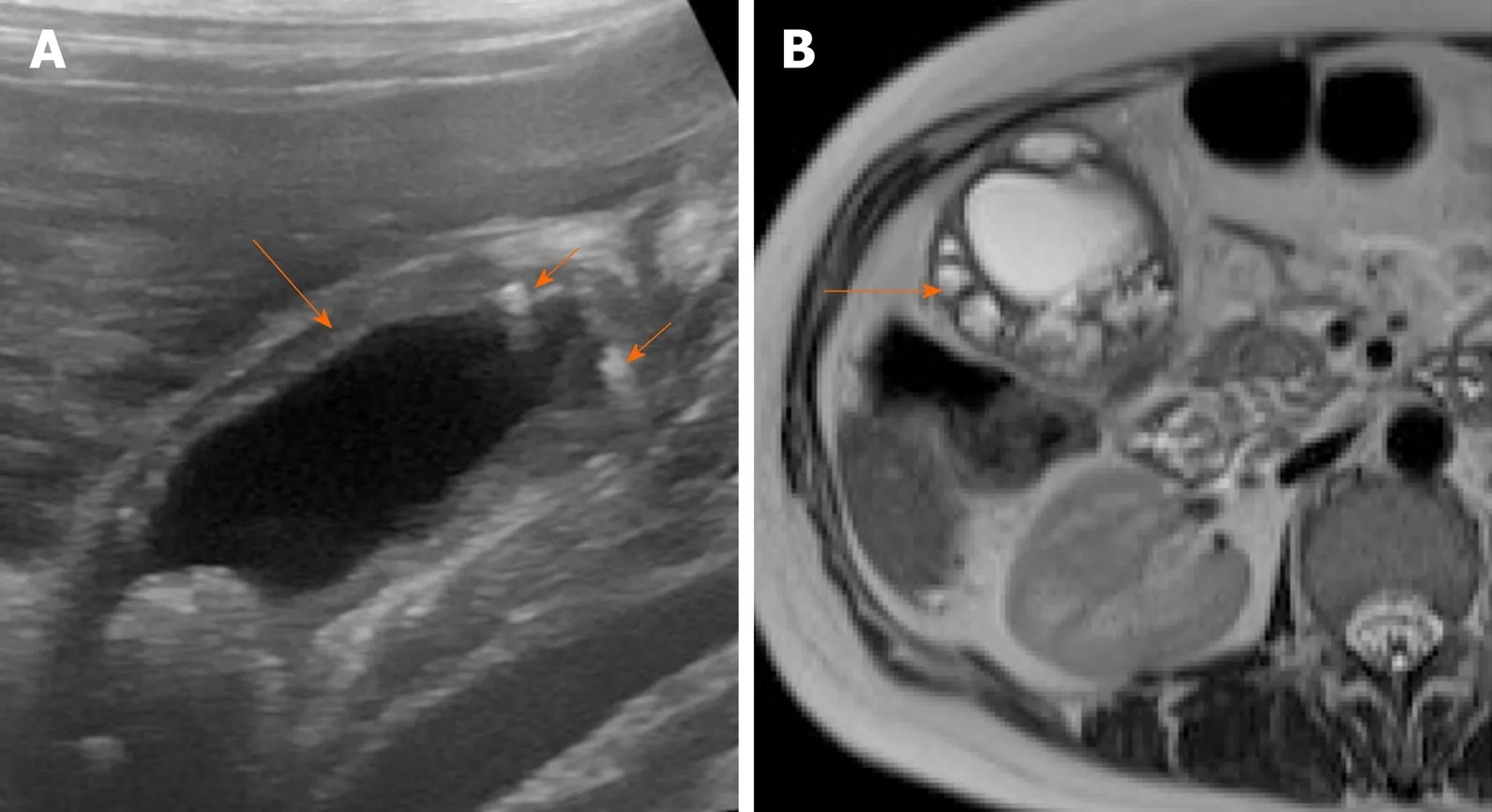

Figure 7 Imaging findings in adenomyomatosis. A: Ultrasound image shows symmetrical mural thickening (arrow) with echogenic foci showing comet tail artifacts (short arrows); B: T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging shows multiple intramural cystic lesions (arrow).

Differentiation of focal ADM from GBC can be challenging as the intramural echogenic foci in GB fundus can be severely deteriorated by volume artefacts on USG[51]. CEUS combined with conventional USG can improve the diagnostic accuracy in such cases. Location of the lesion in GB fundus, lack of blood flow, intramural anechoic spaces, iso to hypo-enhancement of the inner wall, and intactness of GB wall on CEUS are useful markers for differentiating focal ADM from early-stage GBC[52]. The distinction between GBC and ADM may be challenging on CT. However, if small cystic spaces are seen within the thickened GB wall, ADM is the likely diagnosis[53]. Cotton ball signi.e.fuzzy grey dots in the mural thickening or a dotted outer border of the inner layer (with enhancement being less than the renal cortex) is specific for ADM[54]. Both focal ADM and focal GBC show early homogenous enhancement. Smooth mucosal continuity with surrounding GB epithelium is seen in cases of ADM[55]. Although ADM is not considered to have malignant potential, there have been few case reports which have shown concomitant existence of ADM and GBC[55,56]. Morikawaet al[57]performed a retrospective study in 624 patients who underwent surgical resection of GB with Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses. Three of the resected specimens showed evidence of early-stage GBC, out of the 93 histologically proven ADM. The authors concluded that preoperative diagnosis of primary GBC in the setting of concurrent ADM is difficult.

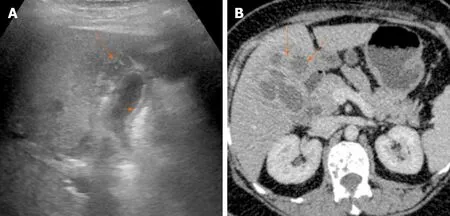

GBC vs xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis

Intramural hypoechoic nodules with a continuous mucosal line are characteristic sonographic features of XGC[58]. It has also been suggested that if the nodules occupy an area of more than 60% of the GB wall circumference, the specicity for the diagnosis of XGC is significantly increased[59]. GB wall thickness, hypoechoic nodules, and the boundary between GB and adjacent liver parenchyma are better evaluated on CEUS as compared to USG. Diffuse GB wall thickening with an intact inner layer has been the most valuable indicator of XGC. Hypo-enhancement time > 80.5 s and hypoechoic nodules are other important indicators of XGC[60]. Boet al[61]reported a sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 93% respectively, for differentiating GBC and XGC on CEUS. On MRI, XGC shows a continuous mucosal line with T2 hyperintense foci in the thickened wall. GBC shows early enhancement and lower ADC values as compared to XGC[62]. There is an emerging role of chemical shift imaging for the diagnosis of XGC in cases where hypoattenuating nodules are obscured. Few case reports have shown that the presence of fat within the thickened GB can help in distinguishing XGC from GBC[63-65]. Features such as diffuse GB wall thickening, intact mucosa, intramural hypoattenuating nodules, absence of hepatic invasion, and intrahepatic dilatation favor the diagnosis of XGC (Figure 8)[66-68]. Sensitivity and specificity of 83% and 100% respectively were reported if three out of these five features were used for the diagnosis of XGC[66]. However, preoperative diagnosis may be challenging and the diagnosis of XGC can be made confidently only on histopathology[69]. XGC shows some overlapping features with GBC. Regional lymphadenopathy has been associated with approximately 62.5% of XGC cases according to a study. In the same study, hypoattenuating nodules were more commonly seen in XGC than GBC (P< 0.001)[30]. CT has been shown to have moderate sensitivity (67%-78%), poor specificity (22%-33%), and moderate to substantial overall inter-reader reliability (ƙ-0.43-0.70) in differentiating GBC from benign GB pathologies (acute cholecystitis and XGC)[70]. Surekaet al[71]reported a discontinuous mucosal line in 73.3% of the patients with XGC in a series of 30 patients. Few case reports of XGC have shown irregularly thickened walls with infiltration into adjacent organs[72]. XGC can be mistaken for GBC intraoperatively on gross examination. A combination of gross examination of the mucosa and intraoperative frozen section examination, especially in areas of high suspicion of cancer, can accurately differentiate XGC and GBC and can also detect the simultaneous presence of both entities[73]. This may prevent extended resections in cases of XGC.

Figure 8 Imaging findings in xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. A: Ultrasound image shows symmetrical echogenic inner layer (short arrow) with multiple hypoechoic intramural lesions (arrow); B: Contrast enhanced computed tomography image shows multiple intramural hypodense lesions (arrows).

GBC vs chronic cholecystitis

Generally, arterial enhancement of the thick inner layer that shows isoattenuation to hepatic parenchyma during the venous phase; or enhancing thick inner layer in both phases, is seen in GBC. Cases of chronic cholecystitis show an isoattenuating thin inner layer during both the phases[74].On dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, chronic cholecystitis shows early smooth enhancement, whereas GBC shows early irregular enhancement. The outer margin of early enhancement in GBC correlates with the extent of the tumor[75].

Acute vs chronic cholecystitis/XGC

USG findings of acute cholecystitis include GB wall thickening of more than 3 mm, presence of mural edema, GB distension > 40 mm, and presence of pericholecystic or perihepatic fluid (C sign)[76]. Eliciting a positive sonographic Murphy’s sign has a sensitivity of 92% in the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. The presence of gallstones along with diffuse GB wall thickening has a positive predictive value of 95% for the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis[76]. Diffuse GB thickening and gallstones are also seen in chronic cholecystitis, however, due to associated mural fibrosis, the GB is usually contracted and pericholecystic fluid is generally absent[7,76]. As previously described, XGC is associated with cholelithiasis, GB wall thickening (focal or diffuse), and the presence of intramural hypoechoic nodules with continuous mucosal line[7,58].

In a recent retrospective study to differentiate acute and chronic cholecystitis on CT, it was found that acute cholecystitis had significantly increased GB dimensions (both long and short axes), increased wall thickening, mural striations, pericholecystic fluid and adjacent liver parenchyma enhancement (P< 0.001). Increased mural enhancement was more commonly seen in chronic cholecystitis (P= 0.001)[77].

Rare causes of GB wall thickening

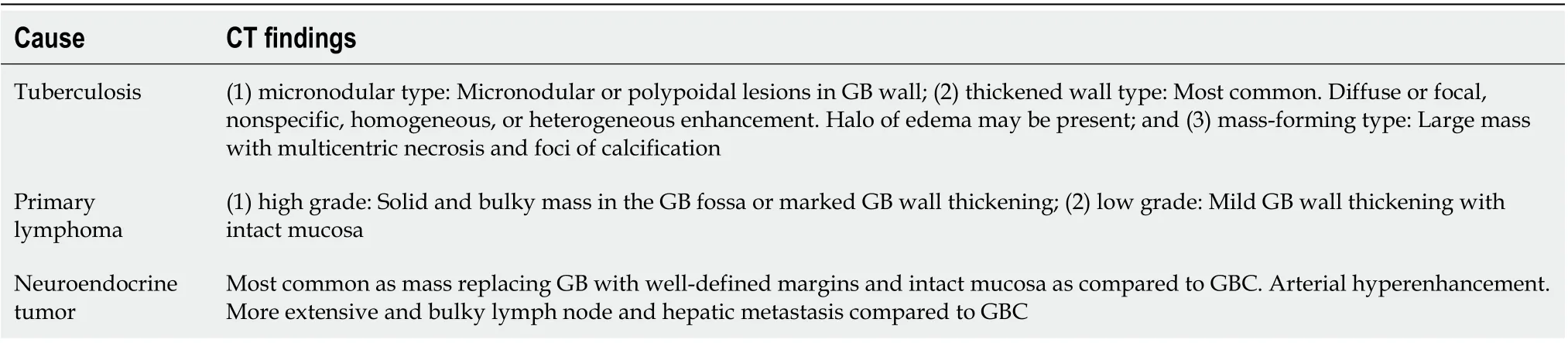

Tuberculosis, lymphoma, neuroendocrine tumor, and metastasis represent rare causes of GB involvement[78-81]. The features of these lesions are tabulated in Table 5.

Table 5 Rare causes of gallbladder wall thickening and their imaging findings

ROLE OF INTERVENTIONAL RADIOLOGY IN GB PATHOLOGIES

Despite the advances in imaging, an accurate diagnosis of GB wall thickening may be challenging at times, and tissue sampling may be required. USG guided fine needle aspiration cytology is a quick, reliable, and cost-effective method, which can be done as an outdoor procedure. USG allows real-time monitoring of the needle tip, and accurate and safe sampling can be done. Studies have shown an accuracy rate of 97%, with false-negative rates of 11% to 41% depending on the expertise[82-85]. However, sensitivity is reduced when malignancy is associated with XGC[86]. Percutaneous biopsy is required for cases that appear unresectable on imaging to look for genetic aberrations, such as ERBB2 amplification, mutations or amplification of the P13 kinase family genes, FGFR mutations or fusion, and aberrations of the chromatin modulating genes[87]. This allows the use of targeted therapy.

Interventional radiologist plays an adjunctive role in preoperative management of cholangitis and postoperative biliary leaks by placing percutaneous drains under USG, CT, or fluoroscopic guidance[88]. Percutaneous drainage of the biliary system and biliary stenting are widely used methods for palliative care in GBC[89]. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an interventional technique that is primarily employed in biliary emergencies like acute severe cholecystitis and cholangitis. Other indications include a second-line approach to access biliary tract for decompression when intra-hepatic radicles are not accessible, to dilate a benign stricture, or stent a malignant stricture[90].

Portal vein embolization is an effective method to facilitate hypertrophy of the residual liver when contemplating extended liver resections. The aim of such a procedure is to achieve a future liver remnant hypertrophy of > 20% of the initial functional liver to prevent postoperative hepatic failure[91]. Various minimally invasive locoregional therapies such as transarterial embolization and percutaneous ablation are under investigation for the treatment of liver metastasis in GBC cases. The commonly used embolization agents are drug-eluting beads and Yttrium-90[92]. Another evolving option is the implantation of hepatic artery infusion pumps, which enable continuous infusion of cytotoxic agents directly into the metastatic lesion[93]. Celiac plexus block is another palliative care therapy offered by interventional radiologists for pain control in advanced cases. The various analgesics agents used are lidocaine, steroids, ethanol, or phenol. Studies have reported improved quality of life and decreased dependence on opioids using this method[94].

APPROACH TO GB WALL THICKENING

It is important to recognize the patterns of GB wall thickening, diffuse or focal, as the conditions associated with these patterns are different. Ancillary findings further help in the characterization of the cause.

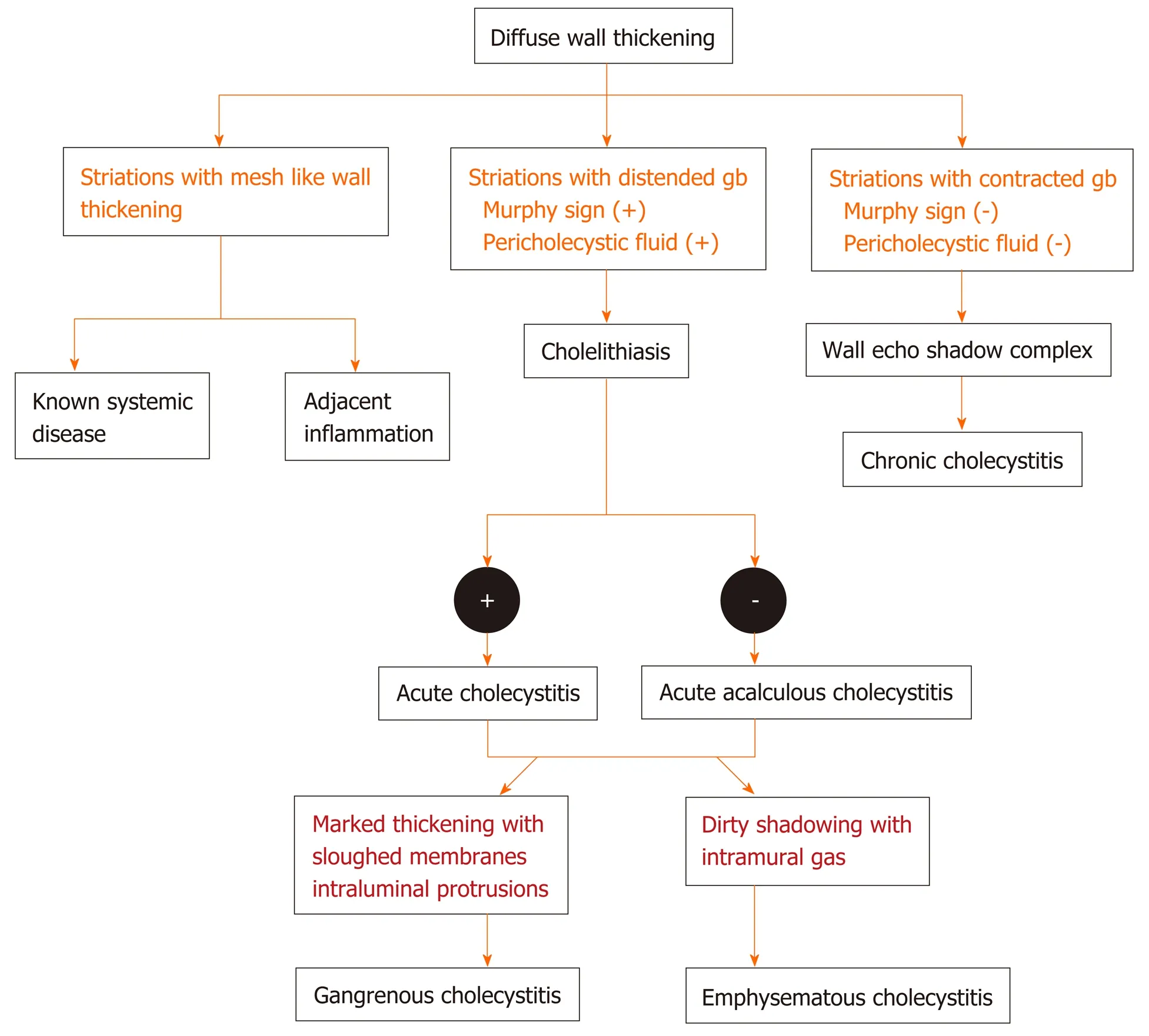

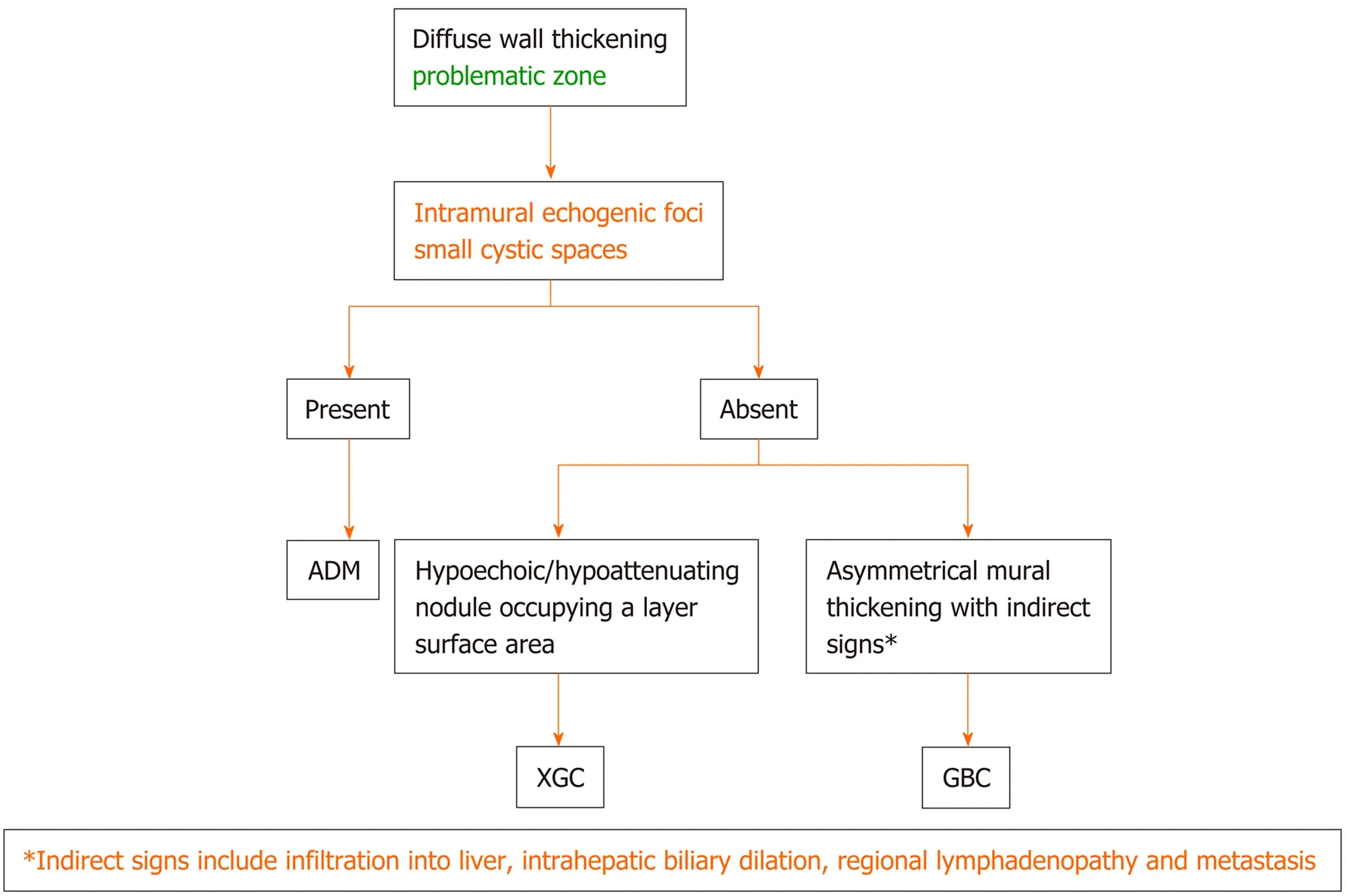

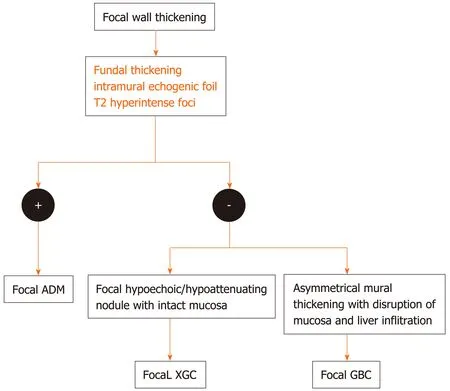

The diffuse pattern of wall thickening can be seen in conditions intrinsic as well as extrinsic to the GB. If a mesh-like diffuse wall thickening is seen in a patient with known systemic disease or adjacent inflammatory reaction, the thickening can be attributed to these extrinsic causes. The presence of Murphy’s sign, with pericholecystic fluid and hydropic distension, as well as cholelithiasis is specific for acute cholecystitis. Absence of Murphy’s sign in a markedly thickened GB with intraluminal membranes should prompt the diagnosis of gangrenous cholecystitis. Dirty shadowing within the thickened GB wall in patients with other features of acute cholecystitis should raise the suspicion for emphysematous cholecystitis, and a CT is warranted in such cases. The absence of cholelithiasis in a critically ill patient with other features of acute calculous cholecystitis is suggestive of acute acalculous cholecystitis. Diagnostic dilemma usually arises in the differential diagnosis of ADM, XGC, and GBC. A multimodality imaging approach may be helpful in such conditions. The focal pattern of GB wall thickening has a narrow differential diagnosis and is seen in conditions intrinsic to GB. An algorithmic approach for the diffuse and focal wall thickening has been outlined in respective flow charts (Figure 9-11).

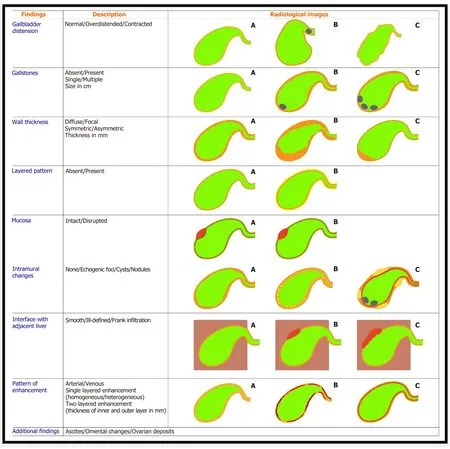

REPORTING FORMAT

In order to increase the objectivity as well as the diagnostic accuracy of imaging findings, it is important to adopt a standardized reporting format that takes into account the key characteristics of the GB, adjacent liver, and distant sites (Figure 12).

CONCLUSION

The radiologist must be aware of the different causes of GB wall thickening. A correct diagnosis is usually established using a combination of multimodality imaging findings, clinical presentation, and laboratory parameters. An understanding of the diagnostic pitfalls in the early stages of GBC and its differentiation from benign conditions is essential for appropriate management.

Figure 9 Flow diagram of the algorithmic approach to diagnose diffuse gallbladder wall thickening.

Figure 10 Flow diagram of the algorithmic approach to diagnose diffuse gallbladder wall thickening: adenomyomatosis vs xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis vs gallbladder carcinoma. ADM: Adenomyomatosis; XGC: Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis; GBC: Gallbladder carcinoma.

Figure 11 Flow diagram of the algorithmic approach to diagnose focal gallbladder wall thickening. ADM: Adenomyomatosis; XGC: Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis; GBC: Gallbladder carcinoma.

Figure 12 Reporting format of the gallbladder wall thickening.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年40期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年40期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Cirrhotic portal hypertension: From pathophysiology to novel therapeutics

- New strain of Pediococcus pentosaceus alleviates ethanol-induced liver injury by modulating the gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid metabolism

- Prediction of clinically actionable genetic alterations from colorectal cancer histopathology images using deep learning

- Compromised therapeutic value of pediatric liver transplantation in ethylmalonic encephalopathy: A case report

- Predicting cholecystocholedochal fistulas in patients with Mirizzi syndrome undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- Novel endoscopic papillectomy for reducing postoperative adverse events (with videos)