Gender differences in clinical outcomes of acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the KAMIR-NIH Registry

Myunhee Lee, Dae-Won Kim,#, Mahn-Won Park, Kyusup Lee, Kiyuk Chang, Wook Sung Chung,Tae Hoon Ahn, Myung Ho Jeong, Seung-Woon Rha, Hyo-Soo Kim, Hyeon Cheol Gwon,In Whan Seong, Kyung Kuk Hwang, Shung Chull Chae, Kwon-Bae Kim0, Young Jo Kim,Kwang Soo Cha, Seok Kyu Oh, Jei Keon Chae, Ji-Hoon Jung; on behalf of KAMIR-NIH registry investigators

1Division of Cardiology, Daejeon St.Mary’s hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, South Korea

2Division of Cardiology, Seoul St.Mary’s hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, South Korea

3Gachon University, Gil Medical Center, Incheon, South Korea

4Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, South Korea d Korea University

5Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, South Korea

6Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, South Korea

7Sungkyunkwan Universtiy, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea

8Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, South Korea

9Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, South Korea

10Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, South Korea

11Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, South Korea

12Yeungnam University Hospital, Daegu, South Korea

13Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, South Korea

14Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan, South Korea

15Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, South Korea

16Institute of Toxicology, Daejeon, South Korea

Abstract Background There are numerous but conflicting data regarding gender differences in outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).Furthermore, gender differences in clinical outcomes with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) following PCI in Asian population remain uncertain because of the under-representation of Asian in previous trials.Methods A total of 13,104 AMI patients from Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry-National Institute of Health (KAMIR-NIH) between November 2011 and December 2015 were classified into male (n = 8021, 75.9%) and female (n = 2547, 24.1%).We compared the demographic, clinical and angiographic characteristics, 30-days and 1-year major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) in women with those in men after AMI by using propensity score (PS) matching.Results Compared with men, women were older, had more comorbidities and more often presented with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and reduced left ventricular systolic function.Over the median follow-up of 363 days, gender differences in both 30-days and 1-year MACCE as well as thrombolysis in myocardial infarction minor bleeding risk were not observed in the PS matched population (30-days MACCE: 5.3% vs.4.7%, log-rank P = 0.494, HR = 1.126, 95% CI: 0.800-1.585; 1-year MACCE: 9.3% vs.9.0%, log-rank P = 0.803, HR = 1.032, 95% CI: 0.802-1.328; TIMI minor bleeding: 4.9% vs.3.9%, log-rank P = 0.215,HR = 1.255, 95% CI: 0.869-1.814).Conclusions Among Korean AMI population undergoing contemporary PCI, women, as compared with men, had different clinical and angiographic characteristics but showed similar 30-days and 1-year clinical outcomes.The risk of bleeding after PCI was comparable between men and women during one-year follow up.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction; Asian population; Gender difference; Percutaneous coronary intervention

1 Introduction

Over the past decade, despite remarkable advances in medical and interventional therapeutics, ischemic heart disease (IHD) remains the leading cause of death worldwide and its prevalence is still increasing and becoming a major cause of morbidity and mortality.[1]Although the overall IHD mortality has declined over the past decade, the rate of decline for women compared with men has been slower in United States as well as in Korea, raising considerable interest about gender differences in clinical outcomes following IHD.[1,2]Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the cornerstone of improving outcomes in acute myocardial infarction.But there is still ongoing debate over the gender differences in outcomes after PCI.Previous studies have shown that female has worse clinical outcomes following PCI compared with male,[3-7]However, after adjustment of confounding variables (such as age, comorbidities and procedure characteristics), sex disparities in outcomes after PCI have showed inconclusive or negative results.[8-16]Owing to increased public awareness campaigns targeting women such as the American Heart Association’sGo redcampaign,a decrease in gender gap in the treatment, implementation of evidence-based pharmacologic therapies and the development of new interventional technologies, it is unclear whether the gender differences after PCI in AMI setting are still present in contemporary era.Therefore, we conducted this study to examine the association between sex and clinical outcomes after PCI among AMI patients using real world population in the current era.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and patient population

The data were obtained from the database of the Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry-National Institutes of Health (KAMIR-NIH).The KAMIR-NIH is a prospective,multi-center, web-based observational cohort study to develop the prognostic and surveillance index of Korean patients with AMI from 15 centers in Korea and was supported by a grant of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from May 2010 to June 2015.The study flow chart is displayed in Figure 1.Initially, 13,104 patients were included in this analysis.Among them, 2,193 patients who did not undergo PCI and 343 patients with missing data were excluded.The remaining 10,568 patients with AMI performing successful PCI were categorized into two groups according to sex (male: 8021 (75.9%), female: 2547 (24.1%)).All participated centers are high-volume centers for coronary angiography (CAG) with PCI and have used the same study protocol.This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of each participating institution and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.Trained study coordinators at each participating institution collected the data using a standardized format.Standardized definitions of all variables were determined by steering committee board of KAMIR-NIH.

Figure 1.Study population.PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty.

2.2 PCI procedure and medical treatment

CAG and PCI were performed according to the standard guidelines at the time of procedure.[17]Antiplatelet therapy and administration of periprocedural anticoagulation were administered in accordance with the standard regimens.Aspirin (loading dose, 200 mg) plus clopidogrel (loading dose, 300 or 600 mg) or ticagrelor (loading dose 180 mg) or prasugrel (loading dose 60 mg) were prescribed for all patients before or during PCI.After the procedure, aspirin(100-200 mg/day) was maintained indefinitely.Patients with drug-eluting stent (DES) were prescribed clopidogrel(75 mg/day), ticagrelor (90 mg twice/day), prasugrel (10 mg/day) for at least 12 months.The choice of procedural applications related to PCI such as pre-dilation, direct stenting, post-adjunct balloon inflation, use of imaging devices(e.g., intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography, fractional flow reserve), and administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa-receptor blockers and the cardiac medications were left to the discretion of the treating physician.

2.3 Definitions

The diagnosis of AMI was based on the detection of a raise and/or fall of cardiac biomarkers (creatine kinase-myo-cardial band (CK-MB) and troponin I or T) with at least one value above the 99thpercentile upper reference limit and with at least one of the following: symptoms of ischemia,new ischemic ECG changes, development of pathological Q waves, imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality in a pattern consistent with an ischemic etiology.[18]Diabetes mellitus (DM)was defined as a fasting glucose concentration of ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, a blood glucose concentration of ≥ 11.0 mmol/L on a 75 g, 2 h oral glucose tolerance test, or the use of antidiabetic therapy.Hypertension (HTN) was defined as a history of a systolic blood pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg, a diastolic pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive therapy.Dyslipidemia was defined as a fasting total cholesterol concentration of ≥ 220 mg/dL, a fasting triglyceride concentration of ≥ 150 mg/dL, or the use of antihyperlipidemic therapy.Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as a glomerular filtration on admission of < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2.The glomerular filtration rate was calculated according to the abbreviated Modification of Diet and Renal Disease Study formula.[19]

2.4 Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoint was a one year major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), composite of cardiac death (CD), myocardial infarction (MI), target vessel revascularization (TVR) and cerebrovascular accident(CVA).All deaths were considered as cardiac unless an unequivocal non-cardiac cause was established.CD was defined as any death due to a proximate cardiac cause such as MI, low-output failure, arrhythmia, unwitnessed death and all procedure-related deaths, including those related to concomitant treatment.[20]MI was defined as newly developed Q wave, raised CK-MB, troponin I or T above the normal ranges, typical ischemic symptom accompanied with ST elevation.TVR was defined as percutaneous or surgical revascularization of the stented lesion including 5 mm margin segments and more proximal or distal, newly developed lesion.CVA were defined as a stroke or cerebrovascular accident with loss of neurological function caused by an ischemic or hemorrhagic event with residual symptoms at least 24 h after onset or leading to death.The secondary endpoints were all- cause death, heart failure, stent thrombosis and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI)major and minor bleeding[21]at one year.Heart failure was defined as sudden worsening of the signs and symptoms of heart failure, which was measured as a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of less than 40% during follow-up.Stent thrombosis was evaluated according to the Academic Research Consortium Definitions.[22]TIMI minor bleeding was defined as overt clinical bleeding associated with a fall in hemoglobin of 3% to less than or equal to 5 g/dL or in hematocrit of 9% to less than or equal to 15% (absolute).All adverse events were confirmed through the source documents, including medical records and telephone interviews, and were also adjudicated by the Steering Committee of Chonnam National University Hospital.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and categorical data are presented as absolute values and percentages.Differences between the groups of categorical variables were analyzed by chi-square or Fisher exact test as appropriate and differences between the groups of continuous variables were analyzed by the 2-tailed Student’sttest.The incidences of the primary endpoints according to sex were estimated at 12 months and were displayed in tables and Kaplan-Meier curves.The log-rank test was performed to compare the incidences of the endpoints between the groups.Based on the significant variables (P< 0.05), propensity score (PS) analysis was performed to reduce bias due to confounding variables.Baseline demographic, clinical and angiographic characteristics were compared within the PS matched group.PS was computed by non-parsimonious multiple logistic regression analysis (C-statistics =0.927).Matching was performed with the use of a 1: 1 nearest neighbor matching, from initial 7 to 1 digit.We confirmed the model reliability with goodness of-fit test (P=0.273).In the matched cohort, paired comparisons were performed with the use of McNemar’s test for binary variables and a pairedt-test for continuous variables.All analyses were two-tailed, and clinical significance was defined asP< 0.05.All statistical analyses were performed using a Statistical Analysis Software (SAS, version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

From May 2010 to June 2015, a total 10,568 patients with AMI at 15 medical centers in Korea who underwent successful revascularization were enrolled in this analysis.

3.1 Baseline characteristics of study population

Baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics were significantly different between sexes (Table 1).Compared with men, women were significantly older (71.8± 10.1vs.60.7 ± 11.9 years,P< 0.001), more likely to have DM, HTN and CKD, which were known risk factors of coronary artery disease (CAD).At the time of AMI presentation, women were more frequently presented with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI),severe left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction (LVEF ≤40%, 17.6%vs.14.2%), had a higher incidence of a Killip class ≥ II, showed a higher level of proBNP and had lower hemoglobin.More women had a prior history of heart failure and CVA whereas men had a higher percentage of history of previous MI.During the index AMI hospitalization, women were treated more often with potent P2Y12 inhibitor (such as prasugrel and ticagrelor), while men more frequently received glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.At discharge, both men and women were prescribed with similar percentage of antiplatelet agents, β-blocker and RAAS(renin angiotensin aldosterone system) inhibitors.There was no difference of baseline low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level between sexes whereas women had a slightly higher baseline high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP)level than men, but the mean hsCRP level was less than 2 mg/L at baseline in both groups.There were also significant differences in baseline angiographic characteristics between men and women as displayed in Table 2.The most common infarct-related artery was the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and women showed relatively higher proportion of LAD in target vessels and higher rates of multi-vessel diseases.But there were no significant differences in the total number of stents and stent lengths between men and women.

Table 1.Baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics in AMI patients in Crude and Propensity Score matched Population.

Table 2.Baseline angiographic characteristics in AMI patients in Crude and Propensity Score matched population.

3.2 Clinical outcomes of the crude population

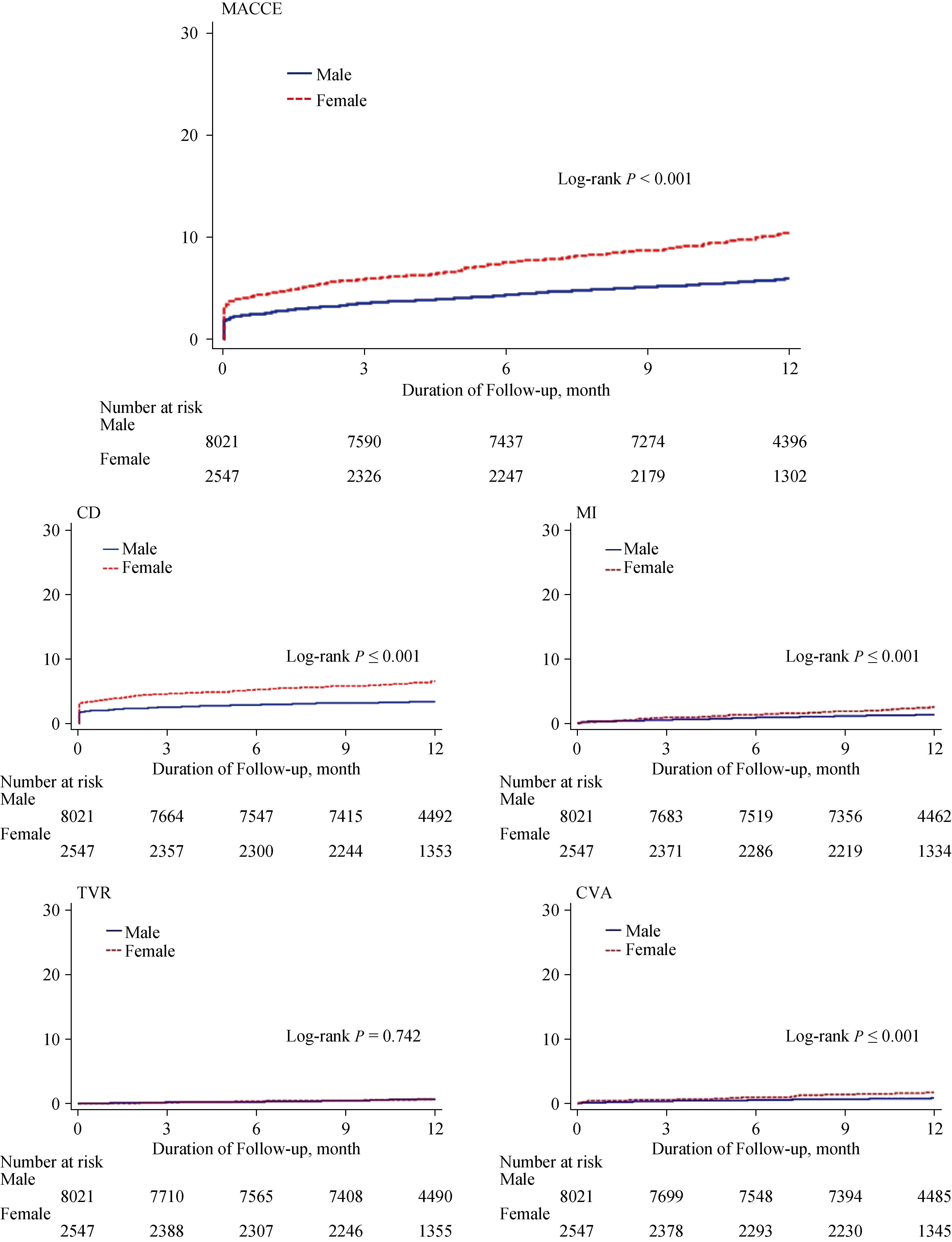

The unadjusted 1-year clinical outcomes among AMI patients who underwent successful PCI are shown in Table 3(upper panel).The cumulative rate of primary composite outcome was significantly higher in women than in men(463 (5.8%)vs.255 (10.0%), HR (95% CI): 1.788 (1.534-2.083),P< 0.001, Table 3 (upper panel)).Individually, the unadjusted cumulative incidence of cardiac death, MI and CVA within one year of the index MI event was significantly higher among women than among men (Table 3(upper panel) and Figure 2).The contrast in the primary composite outcome between men and women was mainly driven by the increased risk for cardiac death in women(266 (3.3%)vs.160 (6.3%), HR (95% CI): 1.928 (1.585-2.346),P< 0.001, Table 3 (upper panel) and Figure 2).In the secondary outcomes, the overall mortality rate was significantly higher in women than in men.(220 (8.6%)vs.380(4.7%), HR (95% CI): 1.863(1.578-2.199),P< 0.001, Table 3 (upper panel)).Heart failure and TIMI minor bleeding occurred more frequently in women than in men (heart failure:172 (6.8%)vs.255 (3.2%), HR (95% CI): 2.214 (1.751-2.578),P< 0.001, TIMI minor: 117 (4.6%)vs.216 (2.7%),HR (95% CI): 1.707 (1.363-2.138),P< 0.001; Table 3(upper panel)) whereas there was no difference in stent thrombosis and TIMI major bleeding between men and women(Table 3 (upper panel)).The Kaplan-Meier curve for the 1-year primary composite endpoint and individual components of primary endpoint are shown in Figure 2.

3.3 Clinical outcomes of the propensity score matched population

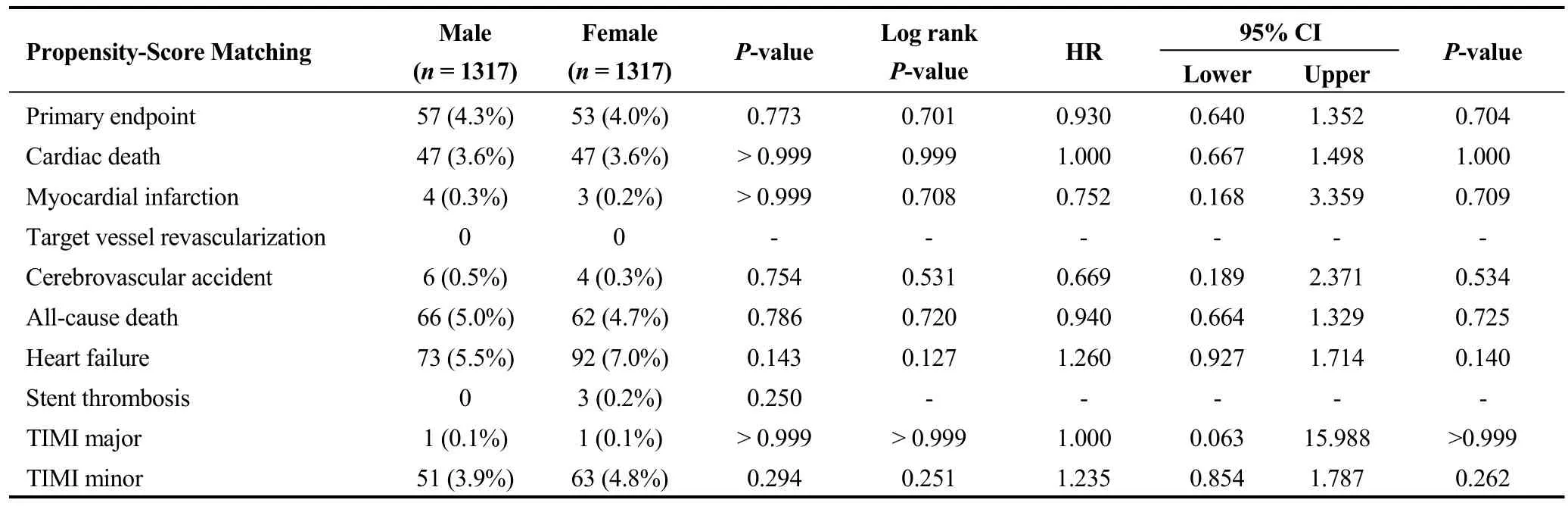

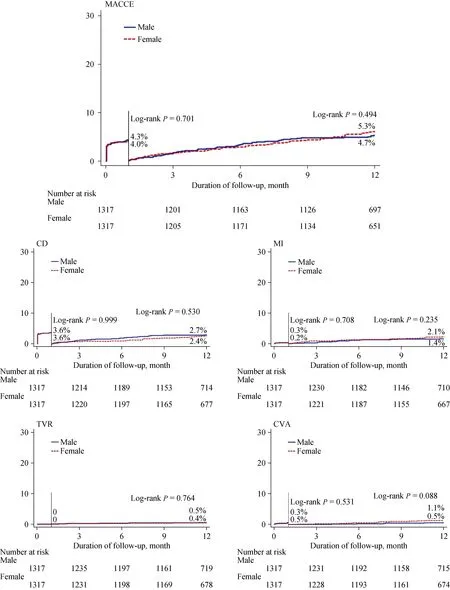

The 1-year clinical outcomes among AMI patients who underwent successful PCI after PS matching are shown in Table 3 (lower panel) and Figure 3.PS matching yielded 1,317 pairs with balanced baseline characteristics including demographic, clinical, laboratory and angiographic features(Table 2 (right panel)).After PS matching, female sex was no longer significantly associated with a higher risk of MACCE (HR (95% CI): 1.032 (0.802-1.328),P= 0.803,Table 3 (lower panel)).All observed differences in eachprimary and secondary outcomes were no longer significant after PS matching: HR (95% CI): 0.938 (0.689-1.278),P= 0.684 for CD; HR (95% CI): 1.308 (0.760-2.251),P=0.331 for MI; HR (95% CI): 1.464 (0.723-2.964),P=0.287 for CVA; HR (95% CI): 0.879 (0.681-1.135),P=0.340 for all-cause death; HR (95% CI: 1.260 (0.927-1.714),P= 0.127 for heart failure (Table 3 (lower panel), Figure 3).We performed a landmark analysis with a prespecifiedlandmark set at one month to evaluate whether sex is associated with short term morbidity and mortality related to PCI in PS matched population.As shown in Table 4 and Figure 4, landmark analysis confirmed that gender difference was not observed in the short-term (30-day) as well as long-term (1-year) clinical outcomes (MACCE, each component of MACCE and bleeding outcomes).

Table 3.One-year clinical outcomes in AMI patients in Crude and Propensity Score matched population.

Figure 2.Kaplan-Meier curve for the 12-month probability of each endpoint in patients with MI undergoing primary PCI comparing men and women before propensity score matching.CD: cardiac death; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TVR: target vessel revascularization.

Figure 3.Kaplan-Meier curve for the 12-month probability of each endpoint in propensity score matched patients with AMI undergoing primary PCI comparing men and women.AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CD: cardiac death; CVA: cerebrovascular accident;MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PSM: propensity score matching; TVR:target vessel revascularization.

Table 4.One-month landmark clinical outcomes in AMI patients in Propensity Score Matched population.

3.4 Bleeding outcomes

We examined the cumulative incidence of TIMI major and minor bleeding event within one-year post index PCI.In general, there were few bleeding events for both men and women.Women had a higher risk of TIMI minor bleeding(4.6%vs.2.7%,P< 0.001, Table 3 (upper panel)), but there is no difference in TIMI major bleeding between gender(Table 3 (upper panel)).After PS matching two populations,sex was no longer significantly associated with bleeding events (Table 3 (lower panel)).

3.5 Subgroup analysis of propensity score matched population

After PS matching, the association of female sex with risk of 1-year MACCE was similar between patients with and those without CAD risk factors (such as DM, HTN,dyslipidemia and smoking status), older (≥ 70 years) and younger patients, patients with preserved LV systolic function and with reduced LV systolic function.(Figure 5) Particularly, among ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients, female had marginally significant increased risk compared with men.(HR (95% CI): 1.326(0.921-1.908),Pvalue for interaction = 0.055).

4 Discussion

This present study demonstrated as follows: (1) clinical and treatment profiles differed between female and male in the Korean AMI patients undergoing primary PCI in the DES-era: women were older and sicker at presentation, had a higher prevalence of NSTEMI, lower LVEF, had more comorbidities such as DM, HTN, CKD and CVA, while men had a higher percentage of obesity, smokers; (2) female showed a higher unadjusted 30-days and 1-year outcomes but showed comparable 30-days and 1-year outcome compared with men in PS matched population (unadjusted incidences of all-cause death, cardiovascular death, and MACCE were all higher in women, whereas these outcome measures became comparable between the women and the men in PS matched population); and (3) women were also more likely to have minor bleeding than men, yet after adjustment, female sex was no longer associated with a higher risk of bleeding events.

Numerous reports have been published regarding the gender disparities in clinical outcomes of CAD patients following PCI, but they showed inconclusive and inconsistent results.[8-16]Traditionally, female sex has been regarded as a prognostic factor of worse clinical outcome after PCI.The suggested reasons for adverse clinical outcome compared with men has been often ascribed to women’s older age at presentation,[23-25]comorbidities,[23,24]less frequent administration of guideline-recommended medical therapy[24,26,27]and less frequent application of invasive procedures such as PCI.[26-28]But, recent studies tended to report that female sex was not associated with worse outcome after PCI.[29-32]However, gender differences in AMI have not been established in an Asian population in the era of second-generation DES.Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate the impact of sex on clinical outcomes after emergency PCI in Korean patients with AMI.Our findings have several important implications.First, although Asian generally hasknown to have a higher prevalence of CAD, more cardiovascular comorbidities and poorer outcomes compared with Caucasians after PCI,[33-35]previous studies regarding the gender differences have been performed in western population, including a relatively small percentage of Asian subgroup.Furthermore, the risk profiles of Korean patients differ from those in Western populations (e.g., Korean patients are older, smoke less frequently, and have less traditional risk factors such as HTN, dyslipidemia and a prior history of MI/CVA/PCI, except for DM).Thus, gender differences in clinical outcomes after PCI in Korean need to be investigated.In the present study, we demonstrated the gender differences no longer exist in contemporary era and female gender itself is not an independent risk factor of clinical outcomes as well as bleeding complications after PCI based on nationwide, multicenter Korean AMI registry.Second, gender differences in outcomes following PCI differ according to the initial clinical presentation.It has been previously shown that outcomes did not differ between male and female patients with stable angina, unstable angina and NSTEMI.[16,36,37]In contrast, among STEMI patients, female exhibited worse prognosis, even after adjustment for multiple variables.[7,27,38-40]In this prospective cohort study, female had a significantly higher unadjusted risk of major cardiovascular events and mortality than men.These could be explained by female’s advanced age, severe initial presentation and underlying comorbidities compared with men.But after PS matching, gender differences in outcomes were no longer observed not only patients with STEMI but also those with NSTEMI.There are plausible explanations for the absence of gender disparity in STEMI patients in this study.First, all participated centers have highly qualified interventional cardiologists (at least five years of experiences of PCI) and high-volume centers (over 300 cases of PCI annually) for CAG with PCI.In Korea, primary PCI facilities are available throughout the country, which enables more timely access to revascularization even in high-risk patients.This situation in Korea might contribute to reduce periprocedural complications and enhance clinical outcomes after PCI in female patients.Second, in this study,study participants exclusively comprised patients receiving newer-generation DES during PCI.Naito et al.reported that in plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA)-era female exhibited lower event-free survival rate compared with men, but the difference has diminished in bare metal stent (BMS)-era,disappeared in DES-era.[31]Because women with AMI have culprit coronary arteries with smaller diameters and thus a potentially high risk of procedure related complications such as rupture, bleeding and restenosis, female patients may benefit more than male patients from the use of DES.This newer-generation DES would enable female patients to tolerate high risk PCI more safely and effectively.Advance in devices and techniques related to PCI, improvement of evidence-based medical therapies, and increased awareness in patients with AMI, have resulted in a reduction in shortand long-term morbidity and mortality.

Figure 4.Kaplan-Meier curve and the one-month landmark analysis of probability of each endpoint in propensity score matched patients with MI undergoing primary PCI comparing men and women.CD: cardiac death; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TVR: target vessel revascularization.

4.1 Study limitations

There are several limitations in this study.First, our results are obtained from a prospective analysis of an observational PCI registry that was subject to missing or incomplete information.Therefore, potential residual biases from measured confounders and biases due to unmeasured confounders might influence the results.To reduce selection bias and residual biases assessing causal effects in observational studies, we used PS-matched (1: 1) analysis.Furthermore,this registry can provide “real world” data on a wide spectrum of unselected patients that underwent PCI procedures in Korea.Second, the 1-year follow-up period was relatively short to determine the long-term clinical outcomes according to gender difference.Further long-term studies will be needed to confirm these findings.Third, because the present study was conducted in a wide diversity of hospital settings and laboratory tests performed separately by the different hospitals, it has an intrinsic limitation itself due to heterogeneity in angiographic, laboratory and procedural parameters and it could have affected outcomes.

5 Conclusions

In this study of contemporary national based AMI patients undergoing PCI, women presenting with AMI were older, had more comorbidities than men, reflecting higher unadjusted 30-days and 1-year mortality rate even following successful PCI.But, gender differences in clinical outcomes after AMI were no longer observed in PS matched population.Our study suggested that gender differences in outcomes after PCI is no longer existed in modern DES-era.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Korea Health Technology R & D Project (2016-ER6304- 01), Ministry of Health & Welfare (HI13C1527), South Korea.The authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年11期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年11期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- ARNI and SGLT2i: a promising association to be used with caution

- Pulmonary hypertension concurrent with pericardial effusion and superior vena cava syndrome: who is the initiator?

- Geriatric issues in patients with or being considered for implanted cardiac rhythm devices: a case-based review

- Medical management of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis in patients non-eligible for transcatheter aortic valve implantation

- Ablation strategies for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy:a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Plasma levels of Elabela are associated with coronary angiographic severity in patients with acute coronary syndrome