Impact of proton pump inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients after acute myocardial infarction: a propensity score analysis from China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) registry

Wen-Ce SHI, Si-De GAO, Jin-Gang YANG, Xiao-Xue FAN, Lin NI, Shu-Hong SU, Mei YU, Hong-Mei YANG, Meng-Yue YU,#, Yue-Jin YANG,# on behalf of China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) Registry study group

1Department of Cardiology, State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

2Medical Research and Biometrics Center, State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases,Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

3Xinxiang Central Hospital, Xinxiang, Henan Province, China

4Langfang People’s Hospital, Langfang, Hebei Province, China

5First Hospital of Qinhuangdao, Qinhuangdao, Hebei Province, China

Abstract Background Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are recommended by the latest guidelines to reduce the risk of bleeding in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients treated with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).However, previous pharmacodynamic and clinical studies have reported controversial results on the interaction between PPI and the P2Y12 inhibitor clopidogrel.We investigated the impact of PPIs use on in-hospital outcomes in AMI patients, aiming to provide a new insight on the value of PPIs.Methods A total of 23,380 consecutive AMI patients who received clopidogrel with or without PPIs in the China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) registry were analyzed.The primary endpoint was major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) defined as a composite of in-hospital cardiac death,re-infarction and stroke.Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to control potential baseline confounders.Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of PPIs use on MACCE and gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB).Results Among the whole AMI population, a large majority received DAPT and 67.5% were co-medicated with PPIs.PPIs use was associated with a decreased risk of MACCE (Before PSM OR: 0.857, 95% CI: 0.742-0.990, P = 0.0359; after PSM OR: 0.862, 95% CI: 0.768-0.949, P = 0.0245) after multivariate adjustment.Patients receiving PPIs also had a lower risk of cardiac death but a higher risk of complicating with stroke.When GIB occurred, an alleviating trend of GIB severity was observed in PPIs group.Conclusions Our study is the first nation-wide large-scale study to show evidence on PPIs use in AMI patients treated with DAPT.We found that PPIs in combination with clopidogrel was associated with decreased risk for MACCE in AMI patients, and it might have a trend to mitigate GIB severity.Therefore, PPIs could become an available choice for AMI patients during hospitalization.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction; Clopidogrel; Drug interaction; Propensity score matching; Proton-pump inhibitors

1 Introduction

Patients who suffered acute myocardial infarction (AMI)usually had a much worse baseline clinical characteristic,including higher Killip class, unstable hemodynamics and stress condition, which could facilitate gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB).[1]Moreover, GIB was associated with increased mortality and morbidity despite optimal treatment and successful revascularization after an AMI.[2,3]Therefore, the latest guideline have recommended the co-medication of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and dual antiplatelet therapy(DAPT) to minimize the bleeding risk.[4]However, the value of PPIs use in patients receiving clopidogrel has been questioned for years.Pharmacodynamic studies reportedthat the potential interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs would attenuate the antiplatelet function of clopidogrel.[5]Meanwhile, clinical research showed conflicting results of this interaction on cardiovascular outcomes.[6]To date, few existing data have well characterized the current status of PPIs use in a large Chinese population with AMI.In previous observational studies, there might be baseline confounders which cannot be adjusted by statistic model and this would affect the evaluation on PPIs co-medication.Hence, we performed this propensity score matched (PSM)analysis using a national administrative database and explored the effect of PPIs on in-hospital outcomes when co-administered with clopidogrel in AMI patients.

2 Methods

The China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) registry served as a national hospital-based registry and surveillance program for AMI to timely obtain real-world information about clinical characteristics, medical care and outcomes of Chinese patients with AMI across different provinces, prefectures and counties.[7]It was organized and conducted by Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases of China (NCCD).The final inclusion criteria met the third Universal Definition for myocardial infarction(2012).[8]This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov(NCT01874691) and was approved by the institutional review board of all participating hospitals.The Data Management and Statistics Teams are managed by Medical Research and Biostatistics Center, NCCD and all data were protected at all time.Other detailed description about CAMI registry can be found in the trial design article published previously.[7]

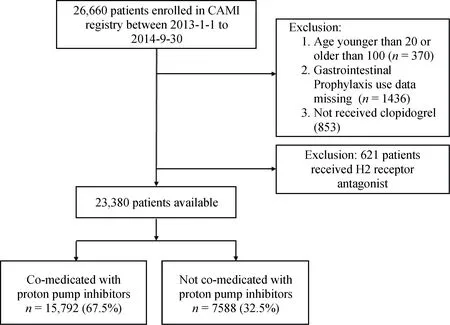

All 26,660 consecutive patients from 108 hospitals in CAMI registry who suffered AMI between January 2013 and September 2014 were enrolled.The following patients were excluded due to: (1) less than 20 and more than 100 years old (n= 370); (2) missing data of the gastrointestinal prophylaxis (n= 1436); (3) not receiving clopidogrel (n=853); (4) using H2receptor antagonists (H2RAs) instead of PPIs (n= 621).PPIs use was determined at the physician’s discretion and was recorded at the time of admission.The specific kind of PPIs was not reported.Finally, a total of 23,380 patients were analyzed (Figure 1).

Demographic characters, past history, admission feature,in-hospital medication and procedure were collected.The CRUSADE (Can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines) bleeding score was calculated since admission as previously described.[9]The primary endpoint was major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) defined as a composite of in-hospital cardiac death, re-infarction, and stroke.Secondary endpoints included each component of the primary endpoint and GIB.Re-infarction was defined as an acute MI that occurred within 28 days of initial MI with evidence of recurred ischemic symptoms, ECG changes and elevated cardiac troponin.[8]GIB was defined as clinically evident bleeding (gross hematemesis, heme positive coffee ground emesis, heme positive melena) from alimentary canal.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median with 25thand 75thpercentiles.Categorical variables were described as a number (n) with percentage (%).Differences of baseline characteristics and outcomes betweenpatients with or without PPIs use were assessed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the analysis of variance test or Wilcoxon rank test for continuous variables.The impact of PPIs on in-hospital outcomes was assessed using multivariate logistic regression analysis.Potential relevant risk factors for ischemic and hemorrhagic events were enrolled in the multivariate model,including age, history of hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, stroke, peripheral arterial disease, peptic ulcer disease/helicobacter pylori infection, prior GIB, malignancy,presence of STEMI, hemoglobin, use of aspirin, GPIIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor, oral anticoagulants, heparin/LMWH, βblockers, ACEI/ARB, and treatment with primary PCI, emergent CABG and/or thrombolysis.Odds ratio (OR) were presented with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and a twotailedP< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Figure 1.Patient flowchart for the study cohort.

In order to control the effect of confounding factors caused by baseline characteristics differences between patients with and without PPIs use, we preformed propensity score matching (PSM) for the entire AMI population.A propensity score was estimated for each patient using a logistic regression model.Patients were matched on estimated propensity scores, with replacement, using a nearest neighbor approach.The detailed information about propensity score model can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics

As shown in Table 1, among 23,380 analyzed patients with AMI, 15,972 (67.5%) were co-medicated with PPIs.PPIs users were older and inclined to be female with higher Killip class and hematocrit.They tended to have higher frequent presence of NSTEMI and the history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, peptic ulcer disease and GIB.They also had more chance to receive GPIIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor, heparin/LMWH, and primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).After PSM, 7169 patients had an estimated propensity score that matched to 7169 patients without PPIs use.

3.2 Clinical outcomes

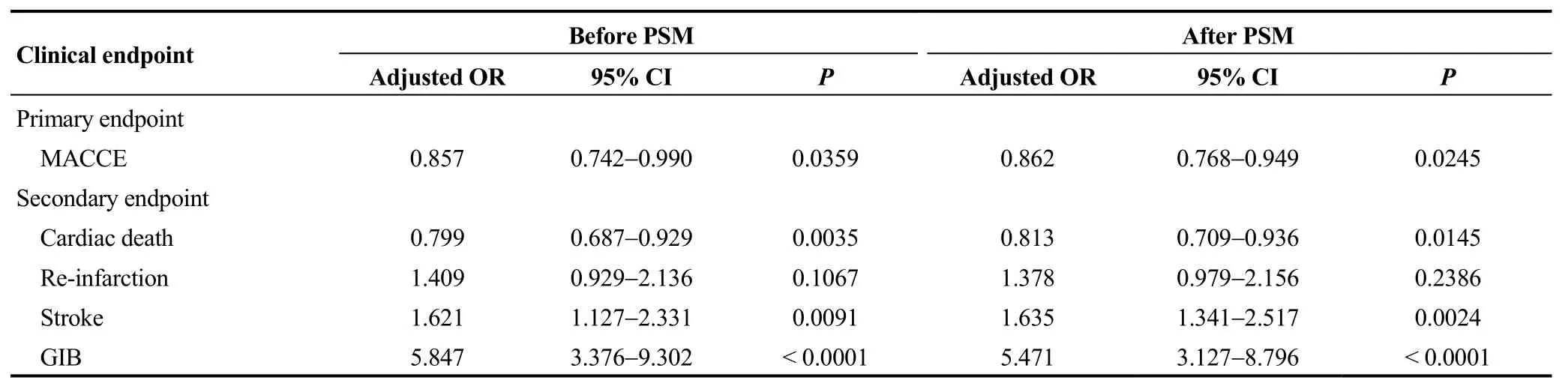

The occurrence of in-hospital MACCE in PPIs population was significantly lower than that in non-PPIs group before (4.1%vs.4.9%,P= 0.0056) and after PSM (4.0%vs.4.7%,P= 0.0025) (Table 2).At multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3), PPIs use was strongly associated with the decreased risks of MACCE (OR = 0.862, 95% CI:0.768-0.949,P= 0.0245) and cardiac death (OR = 0.813,95% CI: 0.709-0.936,P= 0.0145) after PSM, while an increased risk of stroke was observed in PPIs group.

We did not find protective effectiveness of PPIs against GIB before and after PSM (Table 2 and Table 3).However,PPIs co-medication among patients who suffered GIB after AMI showed a nonsignificant trend to alleviate hemoglobin reduction, reduce the chance of using hemostatics and blood transfusion, and decrease the incidence of death caused by GIB (Table 4).

4 Discussion

Clopidogrel is a prodrug needed to be metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) with isoenzyme CYP2C19, and this also played a major role in generating active metabolite of PPIs.Therefore, potential drug-interaction may inhibit the conversion of clopidogrel to its active metabolite and further attenuate its antiplatelet properties[10].A randomized trial revealed that pantoprazole significantly increased platelet aggregation in patients treated with DAPT even after correction for the bias of CYP2C19 polymorphism.[11]Recently, a meta-analysis indicated that the observational studies tended to yield higher rate of adverse events in patients using PPIs, while randomized controlled trials (RCTs)assessing omeprazole compared with placebo showed no difference in ischemic outcomes.This discrepancy may partially due to the selection bias in observational studies.Thus, we made a PSM analysis to eliminate some of these baseline differences between patients who received PPIs and those who did not.

We found that PPIs use was associated with decreased MACCE before and after PSM, which was mainly driven by the reduced risk of cardiac death.However, this finding was different from the recent clinical studies.Of these,TRANSLATE-ACS study12]and PRODIGY trial[13]showed that the concomitant use of PPIs in patients receiving clopidogrel did not significantly affect clinical outcomes, while results from ADAPT-DES study[14]and PARIS study[15]indicated that PPIs in combination with clopidogrel was associated with high platelet reactivity and a greater rate of 2-year adverse events.In this study, we focused on in-hospital outcomes while the other studies evaluated the longterm value of PPIs use.The potential effect of PPIs on clopidogrel might not be obvious in the short run.Moreover,we speculated that PPIs use would improve patients’ compliance to a high-dose of DAPT and intensive anticoagulation therapy, and this may contribute to a lower incidence of cardiac death.

Table 1.Baseline characteristics among all patients according to PPIs use before and after PSM.

Table 2.In-hospital outcomes among all patients according to PPIs use before and after PSM.

Table 3.Multivariate logistic regression analysis among all patients according to PPIs use before and after PSM.

Table 4.GIB severity among patients suffering GIB according to PPIs use before and after PSM.

As for other key endpoints, we found that PPIs had no impact on re-infarction risk.Another US national registry[16]also confirmed that there were no increase in AMI risk among adults prescribed PPIs as compared with H2RAs,indicating that patients should not avoid starting a PPI because of concerns related to MI risk.Unexpectedly, our data showed that patients using PPIs had a higher risk of developing stroke.We supposed that this might due to the higher presence rate of prior stroke and risk profiles in PPIs group even after PSM.Recently, a meta-analysis[17]proved that co-prescription of PPIs and thienopyridines increased the risk of incident ischemic strokes.However, another study[18]revealed that concomitant use of PPIs and clopidogrel was not associated with adverse outcomes after ischemic stroke in Chinese population.These conflicting results underscore the need for future RCTs to assess the safety of PPIs in patients with stroke.As stroke remains one of the leading cause of death in China and the incidence of stroke is higher in Chinese than that in other ethnic population,[19,20]our study may indicate that physicians should avoid prescribing PPIs to high risk patients for stroke.

Consistent with another study in Chinese population, we did not find protectiveness of PPIs against GIB.[21]Yet, another PSM analysis showed the effectiveness of PPIs in reducing the rate of GIB in Japanese population treated with clopidogrel after coronary stenting.[22]This inconsistency might come from study design and the timing when patients received PPIs.Physicians in China tend to prescribe PPIs to AMI patients after emergency procedure, but GIB would have occurred before PPIs were used among AMI patients,especially in those with unstable hemodynamics and high stress state.Even though, our analysis still showed the importance of PPIs use as a remedial method when GIB had occurred.Among 281 patients who suffered GIB in our study (127 after PSM), those treated with PPIs had less hemoglobin reduction and received less drug hemostasis and transfusion.The rate of death caused by GIB was also lower in PPIs group.Although the differences were not statistically significant and the multivariate logistic regressions were not performed because of small sample, these results indicated that PPIs might play a critical role in recovering the injured gastrointestinal mucosa.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

The CAMI registry represents a well-supported registry-base clinical investigation, which not only has large sample size but also serves as a resource to educate physicians and administrative personnel.Our study provided new evidence on the benefit/risk of PPIs use in Chinese hospitalized AMI patients.However, several limitations should be acknowledged.First, the impact of long-term PPIs use on clinical outcomes in patients receiving clopidogrel was not evaluated in our study, and further analysis should assess the long-term prognosis of co-medication.Second, the number of incident GIB was small and multivariate logistic regression could not be performed in Table 4.Finally, although PSM has been used to control baseline confounders,our results may still be subject to selection bias related to this type of observational research.Future large observational studies and RCTs are warranted to further address the potential benefit/risk of PPIs use in AMI patients taking clopidogrel.

4.2 Conclusions

We noticed that our research is the first large-scale study providing evidence on PPIs and clopidogrel co-medication in Chinese AMI population.The co-medication of PPIs and clopidogrel was associated with decreased risk of in-hospital MACCE in AMI patients.When GIB occurred, using PPIs may have a trend to alleviate GIB severity.Our results indicated that PPIs could be an available choice for physician to reduce MACCE and alleviate GIB severity in AMI patients.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the CAMI Study Group for their contributions in the design, conduct, and data analyses for our manuscript.We also appreciate all participating hospitals for their active engagement in enrolling patients, collecting submitting data on patients’ characteristics.This work was supported by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, 2016-I2M-1-009), Twelfth Five-Year Planning Project of the Scientific and Technological Department of China (2011BAI11B02), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81670415).

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年11期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年11期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Incident frailty and cognitive impairment by heart failure status in older patients with atrial fibrillation: the SAGE-AF study

- Comparison of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol for the prediction of thin-cap fibroatheroma determined by intravascular optical coherence tomography

- Plasma levels of Elabela are associated with coronary angiographic severity in patients with acute coronary syndrome

- Gender differences in clinical outcomes of acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the KAMIR-NIH Registry

- Ablation strategies for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy:a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Medical management of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis in patients non-eligible for transcatheter aortic valve implantation