Incident frailty and cognitive impairment by heart failure status in older patients with atrial fibrillation: the SAGE-AF study

Wei-Jia WANG, Darleen Lessard, Jane Saczynski, Robert J Goldberg, Alan S.Go, Tenes Paul,Ely Gracia, David D McManus,

1Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA

2Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA

3Department of Pharmacy and Health System Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA

4Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, CA, USA

Abstract Background Atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) frequently co-occur in older individuals.Among patients with AF, HF increases risks for stroke and death, but the associations between HF and incident cognition and physical impairment remain unknown.We aimed to examine the cross-sectional and prospective associations between HF, cognition, and frailty among older patients with AF.Methods The SAGE-AF (Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Elements in AF) study enrolled 1244 patients with AF (mean age 76 years, 48% women) from five practices in Massachusetts and Georgia.HF at baseline was identified from electronic health records using ICD-9/10 codes.At baseline and 1-year, frailty was assessed by Cardiovascular Health Survey score and cognition was assessed by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.Results Patients with prevalent HF (n = 463, 37.2%) were older, less likely to be non-Hispanic white, had less education, and had greater cardiovascular comorbidity burden and higher CHA2DS2VASC and HAS-BLED scores than patients without HF (all P’s < 0.01).In multivariable adjusted regression models, HF (present vs. absent) was associated with both prevalent frailty (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 2.38, 95% confidence interval [CI]:1.64-3.46) and incident frailty at 1 year (aOR: 2.48, 95% CI: 1.37-4.51).HF was also independently associated with baseline cognitive impairment (aOR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.22-2.11), but not with developing cognitive impairment at 1 year (aOR 1.04, 95%CI: 0.64-1.70).Conclusions Among ambulatory older patients with AF, the co-existence of HF identifies individuals with physical and cognitive impairments who are at higher short-term risk for becoming frail.Preventive strategies to this vulnerable subgroup merit consideration.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation; Cognitive impairment; Heart failure; Frailty

1 Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) are highly prevalent disorders in American adults that are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, especially among older men and women.[1]These two conditions often coexist and are associated with an increased risk of dying.

The prevalence of AF increases significantly with advancing age.[2]Not surprisingly, individuals with AF are frequently affected by conditions common in older populations, particularly frailty[3]and cognitive decline.[4-6]Frailty and cognitive impairment not only predict poor prognosis but also affect the treatment decisions among patients with AF.For example, clinicians frequently cite frailty as a reason to withhold anticoagulation,[7,8]and cognitively impaired patients with AF are less likely to be offered ablation procedures.[9]Therefore, it is clinically important to identify patients with AF who are prone to become frail or cognitively impaired and manage them proactively.AF often manifests with concomitant HF which has been associated with cognitive decline[10]and is intertwined with frailty.[11]However, among individuals with AF, it is unknown whether those with, as compared to those without HF, are more likely to decline in physical and cognitive wellness.

Using data from the SAGE-AF study, which enrolled patients with AF ≥ 65-year-old and performed serial comprehensive geriatric examinations, we examined whether the presence of HF was associated with frailty and cognition impairment.We hypothesized that patients with AF and HFare more prone to deterioration of frailty and cognitive function over time than individuals with AF only.

2 Methods

2.1 Study sample

Details of the SAGE-AF study and the study inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously described.[12]In brief, the inclusion criteria for SAGE-AF include: (1) have an ambulatory visit at one of four Central Massachusetts practices (University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care Internal Medicine, Cardiology, or Electrophysiology,Heart Rhythm Associates of Central Massachusetts), one practice in Eastern Massachusetts (Boston University cardiology), or two practices in Central Georgia (Family Health Center and Georgia Arrhythmia Consultants); (2) AF is present on an electrocardiogram or Holter monitor or if it is noted in any clinic note or hospital record); (3) be 65 years or older, and (4) have a CHA2DS2VASC[13]risk score ≥ 2.

A total of 1,244 participants completed their baseline examination.A follow-up visit was performed one year after the baseline.All participants provided informed written consent.Study protocols were approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Boston University,and Mercer University Institutional Review Boards.

2.2 Data abstraction

Trained study staff abstracted patient’s demographic and clinical characteristics from the medical record.Information abstracted included participants’ age, sex, race, insurance type, comorbidities relevant to stroke and bleeding risk (e.g.,diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, anemia, chronic kidney disease), and cardiovascular treatments (i.e., use of antiplatelets).Relevant laboratory data, including serum creatinine, hemoglobin, and international normalized ratio values(over the past four weeks), were also abstracted.

2.3 Assessment of HF, frailty, and cognition

The presence of HF was abstracted from the medical records at the time of the baseline in-person study visit.Frailty was assessed by the Cardiovascular Health Survey frailty scale.[14]Its components include weight loss/shrinking, exhaustion, low physical activity, slow gait speed, and weakness.Each component receives a point and the scale ranges from 0-5 (0: not frail, 1-2: pre-frail, 3 or more: frail).Cognition was assessed by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Battery,[15]a 30-item screening tool validated to detect mild cognitive impairment.Higher scores indicate better cognitive function, with a score < 23 indicating cognitive impairment.[16]Frailty and cognition were assessed at the baseline and one-year follow-up visits.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants were compared according to the presence of heart failure using analysis of variance for continuous variables and theΧ2test for categorical variables.Logistic regression was used to examine the relationship of heart failure to frailty and cognition, both at baseline and at one year.In examining the associations between heart failure and frailty, Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race, and education; Model 2 was additionally adjusted for histories of diabetes, hypertension, stroke, lung disease and renal disease.For the association between heart failure and cognition,Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race, and education;Model 2 was additionally adjusted for hearing impairment,diabetes, hypertension, stroke, lung disease, and renal disease.Variables with potential to be confounders but not mediators of the associations of interest were selected into the models.Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).A two-sidedPvalve <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Study population

Participants were on average 75.5 ± 7.1 years old, 48.8%were women, and 84.9% were white.At baseline, 463 (37.2%)individuals had prevalent HF.Individuals with HF were older, less likely to be non-Hispanic white, had less education,and had greater cardiovascular comorbidity burden than individuals without HF.They had higher CHA2DS2VASC and HAS-BLED scores and these individuals were more likely to be taking a second antiplatelet agent and take warfarin than a direct oral anticoagulant (Table 1).At one year, 1097(88.2%) patients attended the follow up visit and 44 (3.5%)individuals had died.

3.2 Heart failure and frailty

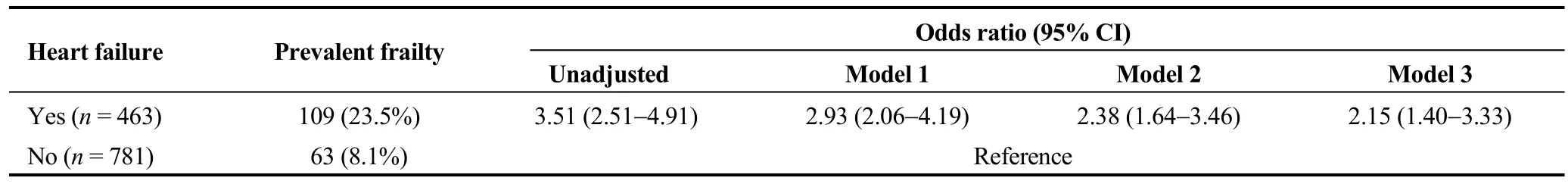

At baseline, individuals with, as compared to those without, HF were significantly more likely to be frail (23.5%versus 8.1%,P< 0.001).This association was attenuated slightly but remained significant after adjusting for several demographic, socioeconomic, psychological, and clinical characteristics (adjusted(a) odds ratio (OR): 2.15, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.40-3.33) (Table 2).

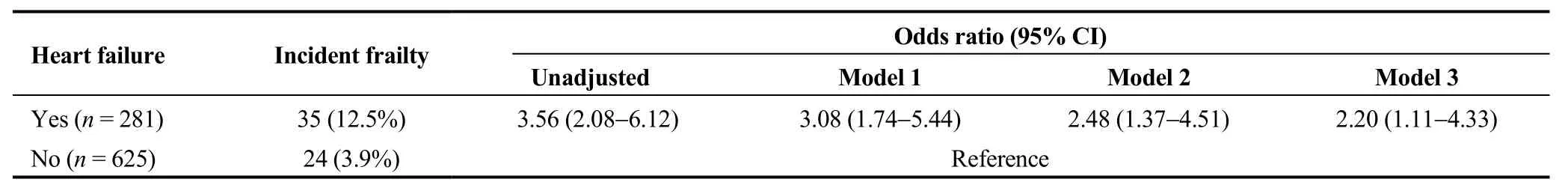

Among individuals who were not frail at the baseline exam, those with HF were three-times more likely to have become frail at the 1-year follow up (12.5%vs.2.9%).Afteradjusting for a variety of demographic, socioeconomic, psychological, and clinical characteristics, this association remained (aOR: 2.20, 95% CI: 1.11-4.33) (Table 3).

Table 1.Baseline characteristics by heart failure.

3.3 Heart failure and cognition

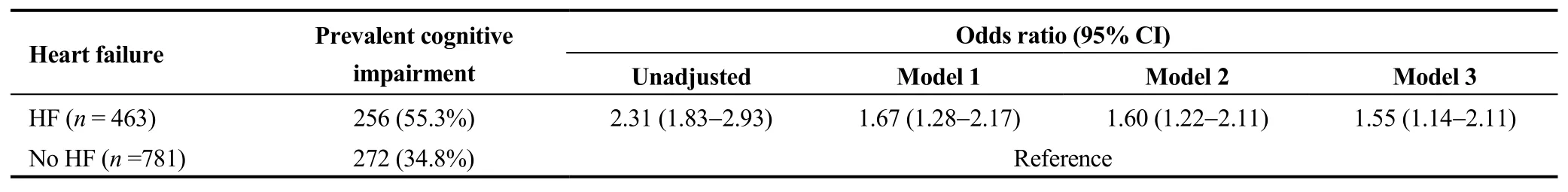

At baseline, individuals with HF were significantly more likely to be cognitively impaired (55.3%vs.34.8%,P<0.001).After adjusting for age, sex, education, hearing impairment, and a history of hypertension, stroke, lung disease,and renal disease as well socioeconomic and psychological factors, this association remained significant (aOR:1.55, 95% CI: 1.14-2.11) (Table 4).

Table 2.Association between prevalent heart failure and frailty at baseline.

Table 3.Association between prevalent heart failure and incident frailty at year one.

Table 4.Association between prevalent heart failure and cognitive impairment at baseline.

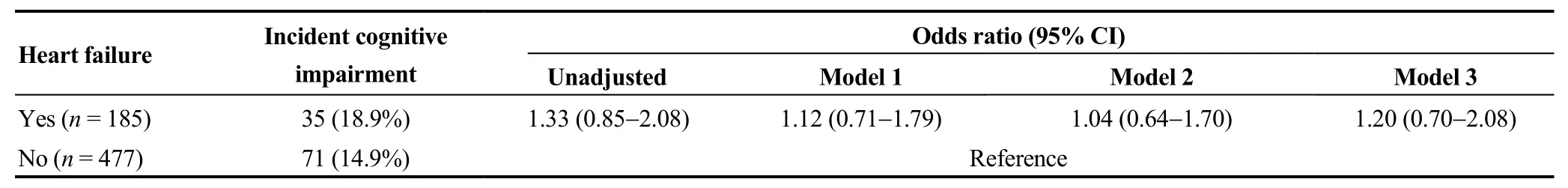

Table 5.Association between prevalent heart failure and incident cognitive impairment at year one.

Among individuals who were not cognitively impaired at baseline, we examined the association between HF at baseline and the development of cognitive impairment in one year.More individuals with HF developed cognitive impairment in year than those without HF (18.9%vs.14.9%)although the difference did not reach statistical significance(Table 5).

4 Discussion

In a contemporary cohort of older men and women with AF, we found that individuals with prevalent heart failure were more likely to be frail and cognitively impaired than individuals without.Furthermore, after one year follow up,prevalent heart failure was associated with incident frailty but not incident cognitive impairment.

AF and HF are known to be intertwining conditions.In the Framingham Heart Study, half of individuals with HF had AF and one third of individuals with AF had HF.Also,the presence of one condition begets the other.Furthermore,the concurrence of AF and HF portended worse mortality than the presence of AF alone.[6]Adding to the prior literatures, our study was the first to evaluate the incident physical and cognitive function by HF status among individuals with AF and demonstrated that individuals with co-occurring HF had higher risk of physical and cognitive impairment than those with AF alone.As shown in our data, older individuals with HF and AF often have more medical problems than those with AF alone, which may explain the association between HF and frailty among older individuals with AF.As frailty is predictive of mortality and poor quality of life in individuals with AF,[17,18]our finding highlighted that the presence of HF identifies a high-risk group with worse clinical outcomes among older patients with AF.

Individuals with coexisting HF and AF frequently require comprehensive management,[19]including guideline directedmedical therapy for HF, anticoagulation for stroke prevention, and catheter ablation to maintain sinus rhythm as it has been recently shown to reduce mortality and HF hospitalization in this population.[20]There is growing evidence that being frail may preclude patients from benefiting some of these therapies.For example, physicians may withhold anticoagulation in frail patients citing concerns of fall and bleeding.[21]Recently, being frail was associated with higher mortality and more rehospitalization after atrial fibrillation ablation.[22]Also, physicians are often hesitant to offer invasive procedures to frail patients.As we showed that 10% of non-frail individuals with HF and AF became frail in one year of follow-up, there is an urgency to manage these individuals proactively and aggressively before they become frail.Whether interventions can prevent or delay the development of frailty in this population requires further studies.

HF and AF have both been individually associated with cognitive impairment.[5,10]This is in line with the observed additively negative effect of both conditions on cognition:more than half of participants with HF and AF were cognitive impaired and they were 2 times more likely to be cognitive impaired than those with AF alone.We have recently shown that vision and hearing impairment are prevalent in this population.[23]Taken together, the combination of HF,cognitive impairment, and sensory impairment will most likely create communication barriers between patients and caregivers.It obstructs patients’ understanding of the disease and participation of the care and results in management difficulties and poorer clinical outcomes.Further studies are necessary to test whether interventions can improve patient communication and clinical outcomes in this vulnerable population.Unlike previous studies,[10]we did not observe difference in incident cognitive impairment by HF status,which may be due to the shorter follow up duration.

Our study has several strengths.First, we assessed cognition and frailty prospectively with validated instruments.Also, the study population is geographically diverse, and participants have a high prevalence of comorbidities which emulates real-world practice.Several limitations should be mentioned.First, the follow up to date was 1-year and could be short to evaluate change in cognitive function.Second,only 20% of individuals had information regarding the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (n= 260, 63 with reduced EF and 197 with preserved EF).The type of heart failure was not statistically associated with either cognition or frailty.Because of the limited data on LVEF, the finding was not conclusive.However, the lack of modification by type of heart failure and cognitive decline was consistent with prior findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study.[10]Also, it would be ideal to know how many individuals developed and recovered from heart failure during the follow up.However, we did not have information on how many individuals developed incident heart failure during the one year follow up.Further studies on how change in heart failure status affects physical and cognitive function in individuals with AF are needed.The type of AF (paroxysmal or permeant) was not available.Lastly, residual confounding is always possible as it is an observational study.

In conclusion, among older patients with AF, the co-existence of HF identifies a subgroup with more physical and cognitive impairments who are also at higher short-term risk for becoming frail.Preventive strategies to this vulnerable subgroup merits consideration to slow the acceleration of functional decline.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant R01HL126911 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.DDM’s time was also supported by grants R01HL137734, R01HL137794,R01HL13660, and R01HL141434, also from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.The sponsor had no role in study concept and design, acquisition of subjects and/or data,collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or preparation of the manuscript.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年11期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年11期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Impact of proton pump inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients after acute myocardial infarction: a propensity score analysis from China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) registry

- Comparison of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol for the prediction of thin-cap fibroatheroma determined by intravascular optical coherence tomography

- Plasma levels of Elabela are associated with coronary angiographic severity in patients with acute coronary syndrome

- Gender differences in clinical outcomes of acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the KAMIR-NIH Registry

- Ablation strategies for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy:a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Medical management of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis in patients non-eligible for transcatheter aortic valve implantation