Effects of antithrombotic agents on post-operative bleeding after endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal neoplasms and polyps: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Bing-Jie Xiang, Yu-Hong Huang, Min Jiang, Cong Dai

Bing-Jie Xiang, Yu-Hong Huang, Min Jiang, Cong Dai, Department of Gastroenterology, First Affiliated Hospital, China Medical University, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, China

Abstract

Key Words: Endoscopic resection; Antithrombotic; Anticoagulants; Postoperative bleeding; Endoscopic mucosal resection; Endoscopic submucosal dissection

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic resection (ER) is deemed as an effective method for gastrointestinal neoplasia and polyp. ER is an acceptable technique to enableen blocresection of gastric adenomas, early oesophageal, gastric and colorectal cancer and incidence and its related mortality of colorectal cancer[1-3]. This includes polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). For example, patients with oesophageal neoplasia receiving ER can maintain the integrity of oesophageal structure and function, whereas the quality of life can be affected by oesophagectomy[4].

Although the therapeutic effect of ER has been greatly affirmed, Postoperative bleeding as a major complication is still a problem to be solved. Postoperative bleeding after ER is defined as bleeding within 30 d from a mucosal defect shown by massive melena, a decrease in blood hemoglobin level of more than 2 g/dL, or requirement of endoscopic hemostasis or transfusion[1,5,6]. A study has shown that the incidence rate of postoperative bleeding after esophageal or colorectal ESD ranged from 0.0% to 4.6%[7]. And the incidence rate of postoperative bleeding after ESD due to gastric neoplasm ranged from 1.8% to 15.6%[7]. A study that included 3788 cases of polypectomy by Choung found that postoperative bleeding occurred in 42 cases (1.1%)[8]. Another study with 30881 cases of polypectomy by Rutter also reported that the postoperative bleeding developed in 291 cases (0.94%)[9]. Preventive strategies such as acid secretion inhibitors and prophylactic clipping have been developed to reduce the postoperative bleeding risk after ER, but postoperative bleeding cannot be completely avoided. Some factors such as the size of polyp and a patient’s coagulation status have been reported to be associated with the risk of postoperative bleeding after ER.

In recent years, more and more people suffering from cardiovascular disease and/or cerebrovascular disease receive antithrombotic therapy which change patients’ coagulation status and may lead to high risk of postoperative bleeding after ER. The relationship between the postoperative bleeding after ER and antithrombotic agents is still uncertain. With this reason, a systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out to identify whether the use of antithrombotic drugs increases the risk of the postoperative bleeding after ER.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of the hemorrhagic data of different antithrombotic users after ER from published studies. The review and analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines[10].

Search method

We used PubMed, Web of Science and Cochrane Library to search for articles published in English from inception to February 2019. The search queries were: (1) ( ( (antithrombotic OR anticoagulant OR antiplatelet OR heparin OR warfarin OR aspirin)) AND (endoscopic submucosal dissection OR ESD)) AND (bleeding OR hemorrhage); (2) ( ( (antithrombotic OR anticoagulant OR antiplatelet OR heparin OR warfarin OR aspirin)) AND (EMR OR endoscopic mucosal resection)) AND (bleeding OR hemorrhage); (3) ( ( (antithrombotic OR anticoagulant OR antiplatelet OR heparin OR warfarin OR aspirin)) AND (endoscopic polypectomy)) AND (bleeding OR hemorrhage); and (4) ( ( (antithrombotic OR anticoagulant OR antiplatelet OR heparin OR warfarin OR aspirin)) AND (APC OR argon plasma coagulation)) AND (bleeding OR hemorrhage).

Study selection

The studies that met the following inclusion criteria were included: (1) Polypectomy, EMR, ESD, polypectomy incorporated argon plasma coagulation and the hot and cold snare; (2) Randomized controlled trials, retrospective studies or cohort studies were performed to investigate the risk of postoperative bleeding after ER in patients with gastrointestinal neoplasm receiving antithrombotic medication; (3) The incidence rate of postoperative bleeding can be extracted in the antithrombotic medication group and the non-antithrombotic medication group; and (4) Anticoagulants and antiplatelet drugs were incorporated in antithrombotic agents.

The studies were excluded if: (1) The postoperative bleeding rate or antithrombotic therapy information could not be extracted; (2) Antithrombotic drugs and NSAIDS were recorded together; (3) Endoscopic treatment such as biopsy, sphincterotomy or ampullectomy was carried out; (4) Reviews, case reports, guidelines, or animal studies were screened out; (5) The articles were not written in English; and (6) The full text could not be obtained.

Methodological quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to evaluate the quality of the included studies. And the Newcastle-Ottawa scale includes three aspects: Selection, comparability, exposure (retrospective studies) or outcome (cohort studies)[11].

Data extraction

Two authors worked together to extract the basic information about the first author, publication year, country, research method (retrospective/cohort), ER method (ESD/EMR/polypectomy), number, age and gender. Moreover, the odds ratio (OR) and 95%CI of the postoperative bleeding rate were calculated in the antithrombotic group (continued/discontinued) and the non-antithrombotic group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by Stata 12.0. The Cochran’sQtest andI2(P< 0.10 was considered significant) were used to identify heterogeneity. The valueI2of 0-25% indicated insignificant heterogeneity; 26%-50%, low heterogeneity; 51%-75%, moderate heterogeneity; and greater than 75%, high heterogeneity[12]. If there was no significant heterogeneity, the OR and 95%CI were calculated in a fixed-effect model. Otherwise, a random-effect model was used. The funnel plot was used to assess publication bias.

RESULTS

Assessment of the studies

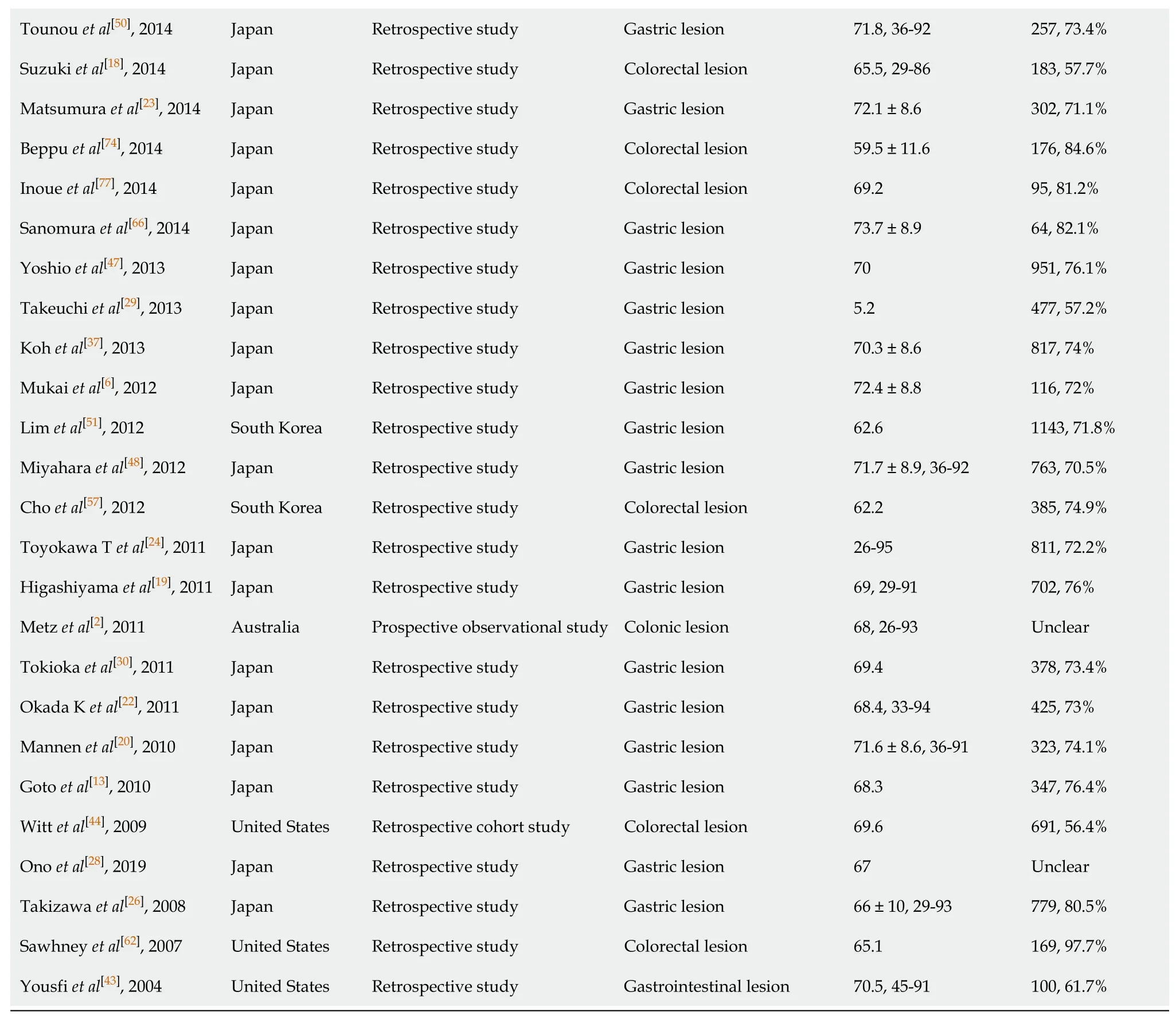

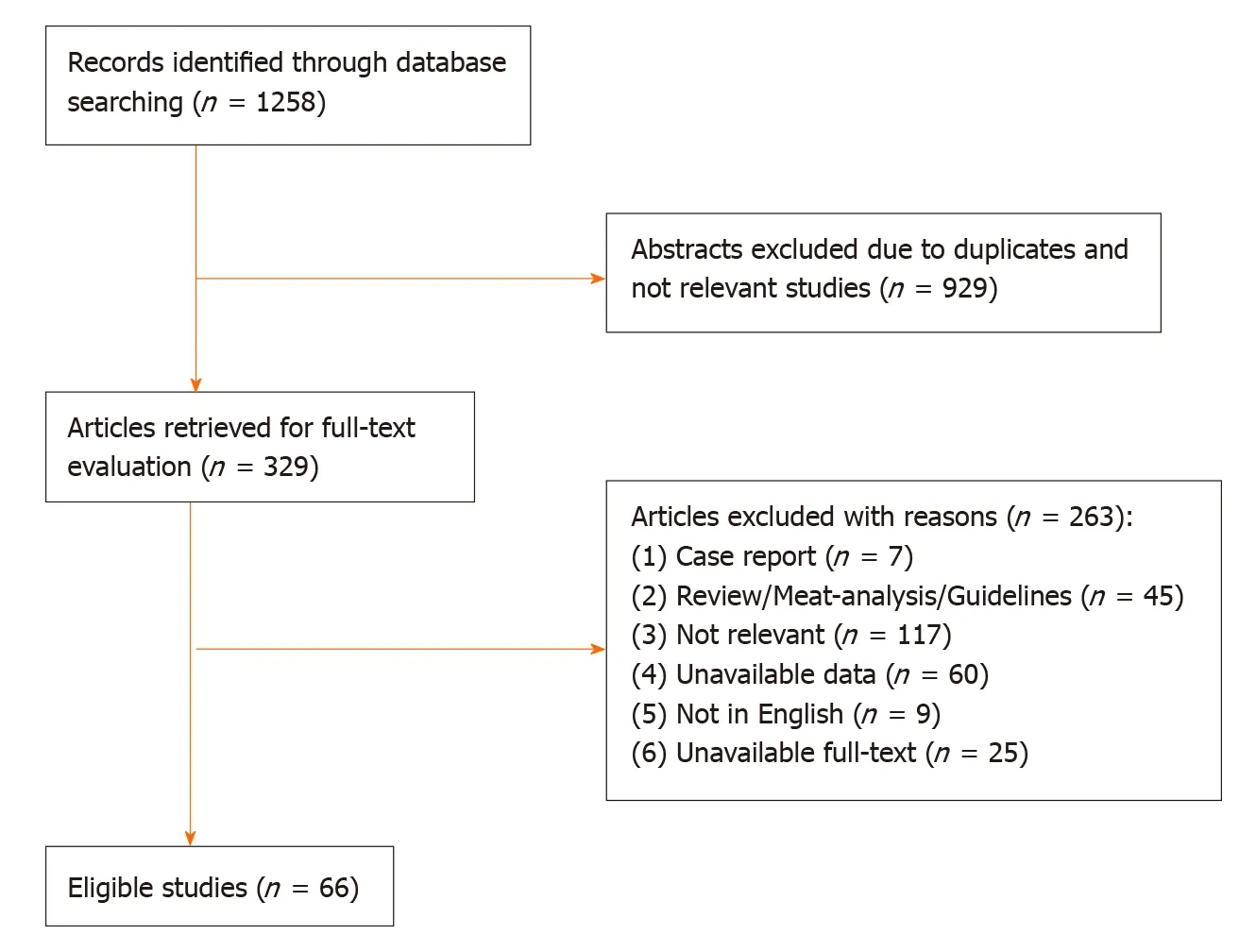

The initial literature yielded 1258 articles (454 articles from PubMed, 679 articles from Web of Science, 125 articles from Cochrane Library). After the exclusion of 929 articles due to duplicates and lack of relevance, 329 articles were retrieved for full text evaluation. 263 articles were excluded after reviewing the full text (Figure 1). Ultimately, 66 studies were included in the meta-analysis (Fifty-nine retrospective studies, seven prospective observational studies). The characteristics of included studies were described in the Table 1. The included studies were carried out from different countries (Fifty from Japan, six from Korean, five from USA, two from Italy, one from UK, one from Australia, one from Holland). The mean age was older than 60 years old in most studies.

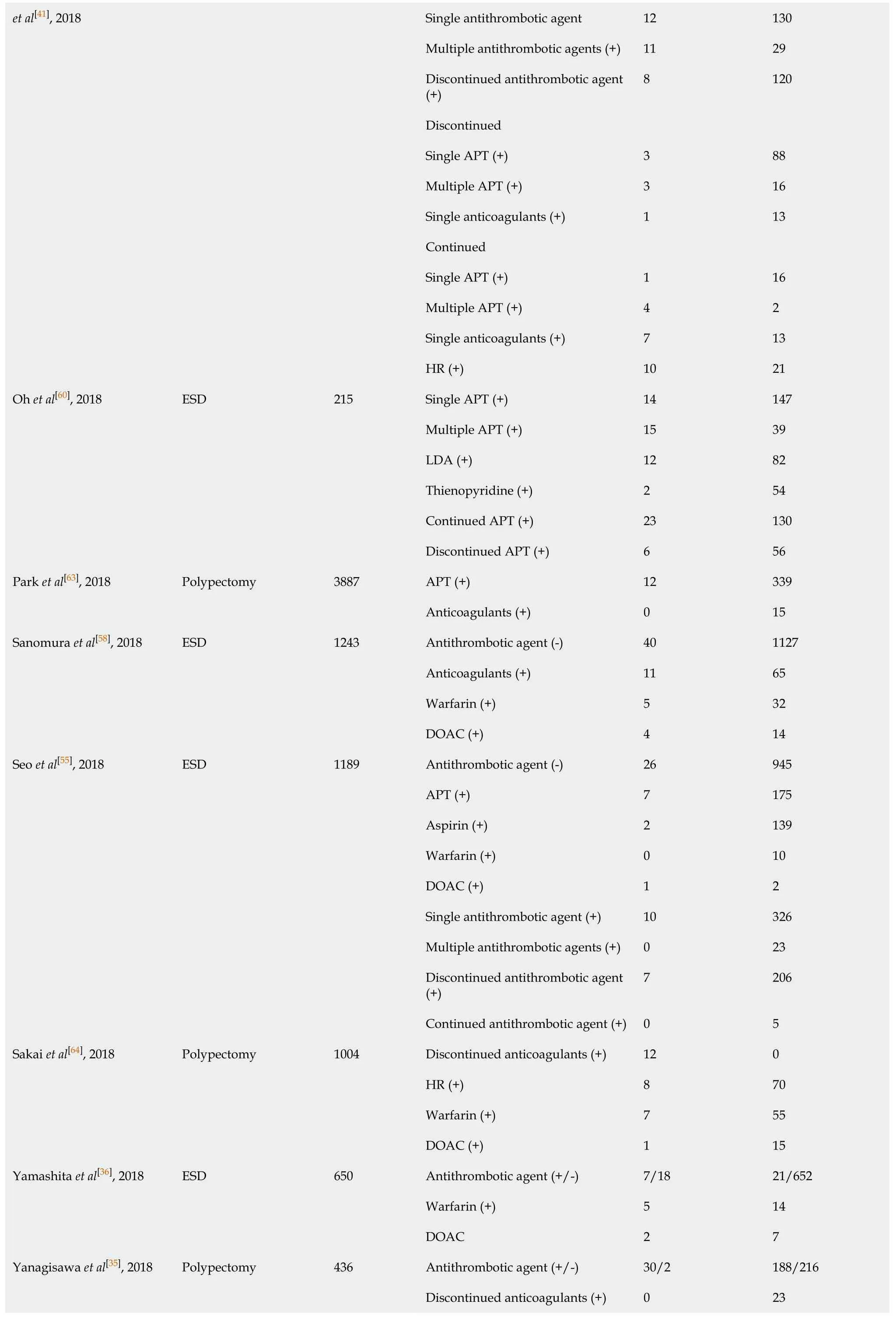

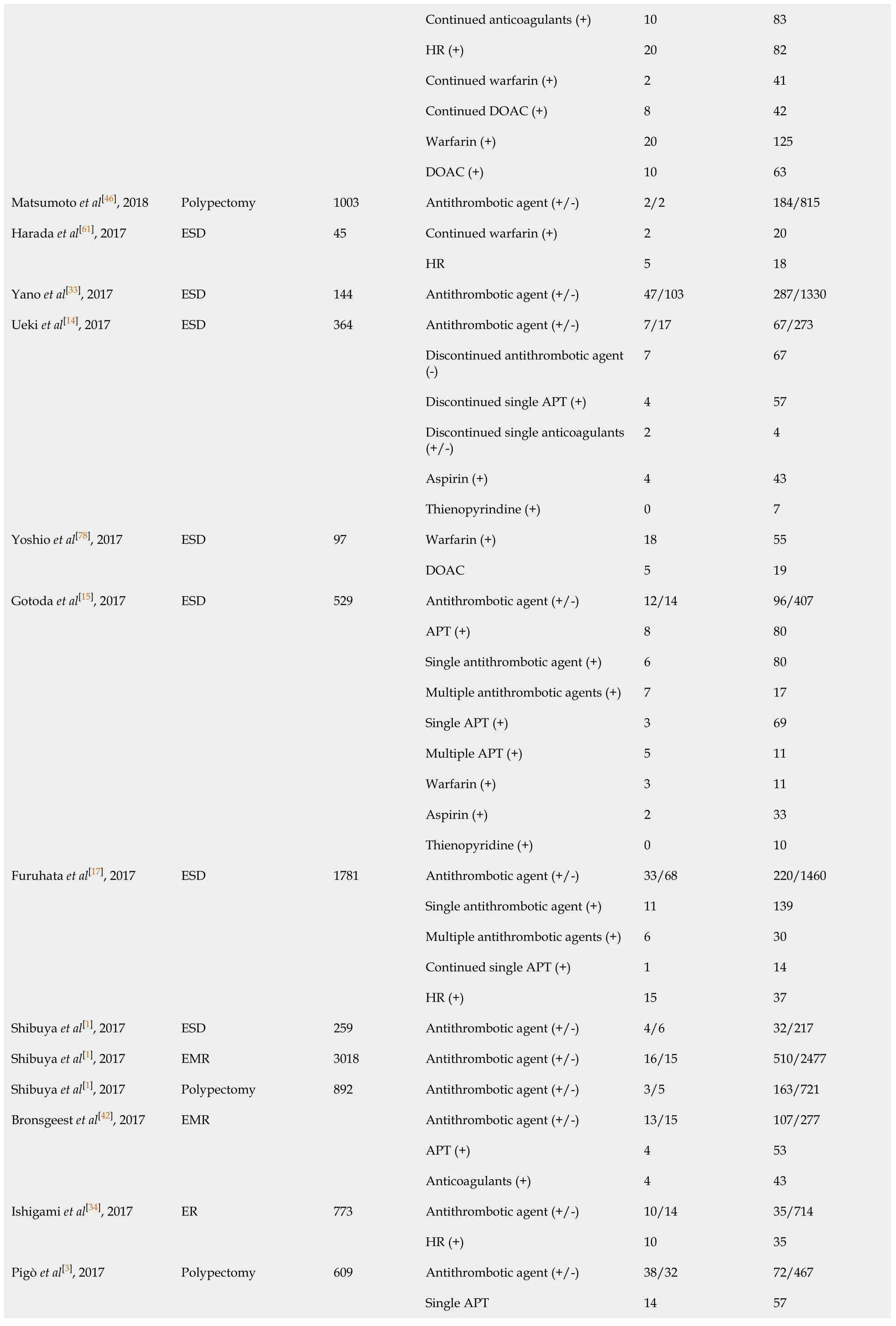

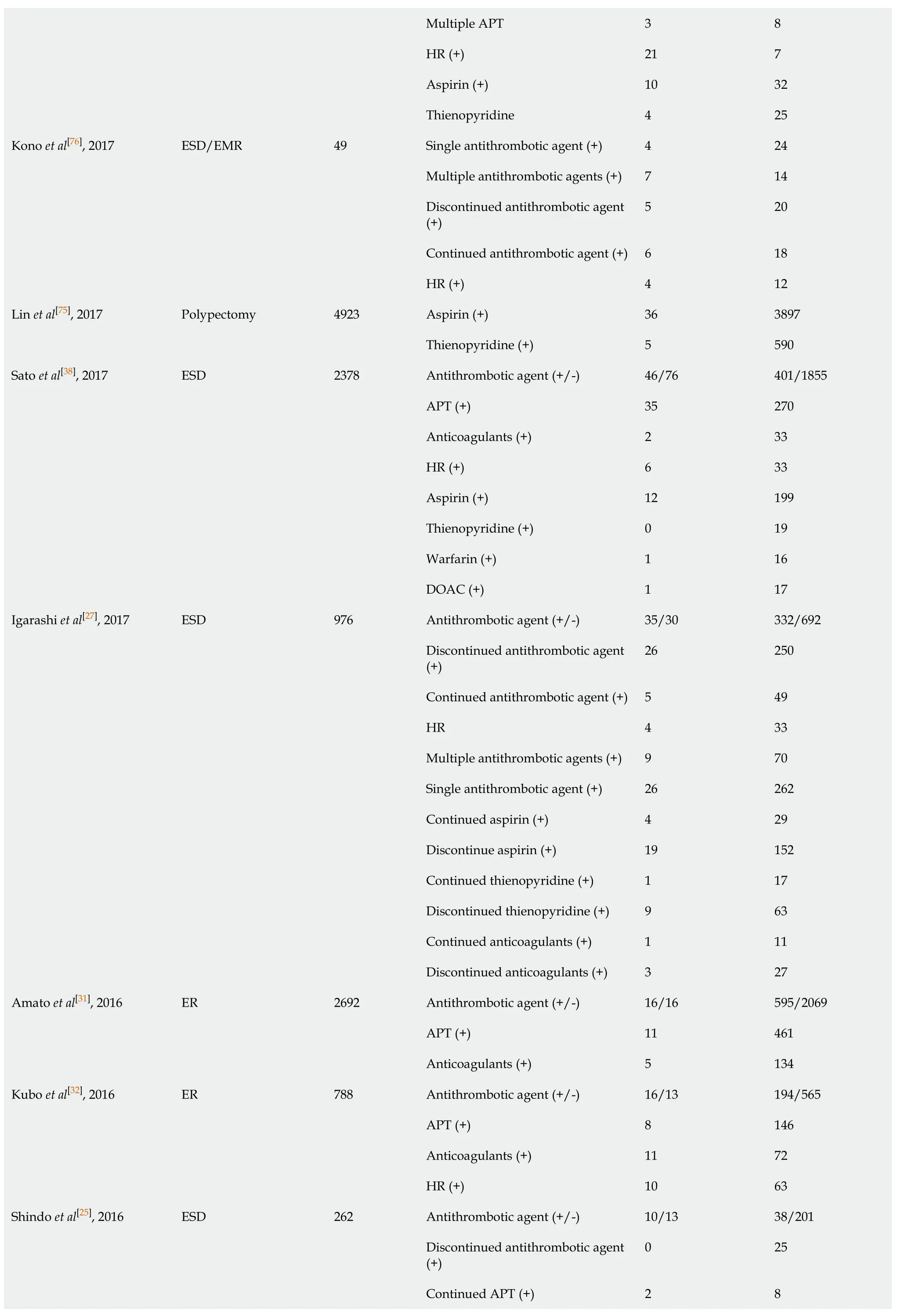

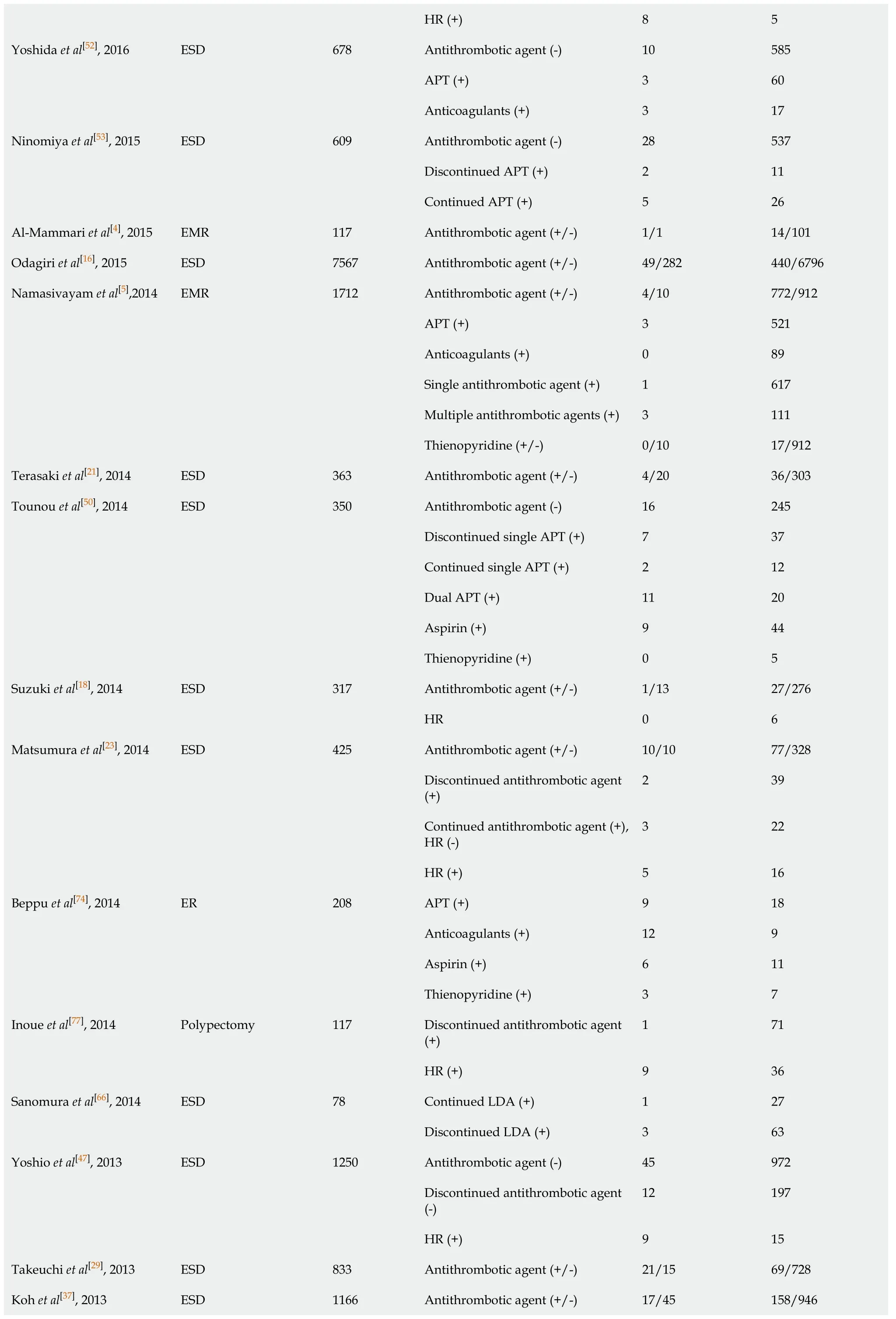

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies and participants

Tounou et al[50], 2014 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 71.8, 36-92 257, 73.4%Suzuki et al[18], 2014 Japan Retrospective study Colorectal lesion 65.5, 29-86 183, 57.7%Matsumura et al[23], 2014 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 72.1 ± 8.6 302, 71.1%Beppu et al[74], 2014 Japan Retrospective study Colorectal lesion 59.5 ± 11.6 176, 84.6%Inoue et al[77], 2014 Japan Retrospective study Colorectal lesion 69.2 95, 81.2%Sanomura et al[66], 2014 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 73.7 ± 8.9 64, 82.1%Yoshio et al[47], 2013 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 70 951, 76.1%Takeuchi et al[29], 2013 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 5.2 477, 57.2%Koh et al[37], 2013 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 70.3 ± 8.6 817, 74%Mukai et al[6], 2012 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 72.4 ± 8.8 116, 72%Lim et al[51], 2012 South Korea Retrospective study Gastric lesion 62.6 1143, 71.8%Miyahara et al[48], 2012 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 71.7 ± 8.9, 36-92 763, 70.5%Cho et al[57], 2012 South Korea Retrospective study Colorectal lesion 62.2 385, 74.9%Toyokawa T et al[24], 2011 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 26-95 811, 72.2%Higashiyama et al[19], 2011 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 69, 29-91 702, 76%Metz et al[2], 2011 Australia Prospective observational study Colonic lesion 68, 26-93 Unclear Tokioka et al[30], 2011 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 69.4 378, 73.4%Okada K et al[22], 2011 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 68.4, 33-94 425, 73%Mannen et al[20], 2010 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 71.6 ± 8.6, 36-91 323, 74.1%Goto et al[13], 2010 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 68.3 347, 76.4%Witt et al[44], 2009 United States Retrospective cohort study Colorectal lesion 69.6 691, 56.4%Ono et al[28], 2019 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 67 Unclear Takizawa et al[26], 2008 Japan Retrospective study Gastric lesion 66 ± 10, 29-93 779, 80.5%Sawhney et al[62], 2007 United States Retrospective study Colorectal lesion 65.1 169, 97.7%Yousfi et al[43], 2004 United States Retrospective study Gastrointestinal lesion 70.5, 45-91 100, 61.7%

Effect analysis

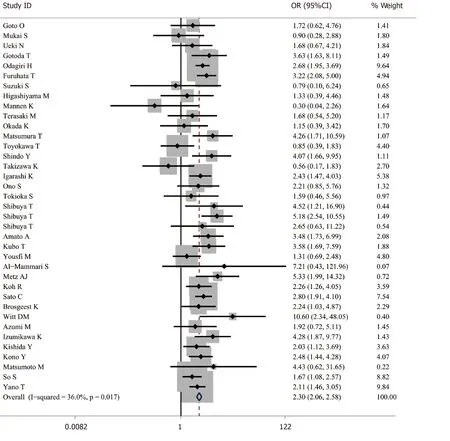

A total of 48691 cases after ER were enrolled, of which 8918 cases were receiving antithrombotic medication and 39773 cases were not taking any antithrombotic drugs[1,2,4,6,13-33]. The average postoperative bleeding rate in the antithrombotic group was 8.44%, while it was 5.28% in the non-antithrombotic group. With the randomeffects model, the risk of postoperative bleeding in the antithrombotic group was higher than the non-antithrombotic group (OR = 2.421, 95%CI: 1.831-3.200,P= 0.000,I2= 82.5%). In addition, a more homogeneous analysis (I2= 36.0%) was carried out after six articles[3,5,29,34-36]were screened out in the sensitivity analysis and the results remained unchanged (OR = 2.302, 95%CI: 2.057-2.577,P= 0.000) (Figure 2). Besides this, the results were not changed when data from retrospective and prospective studies were separately analyzed.

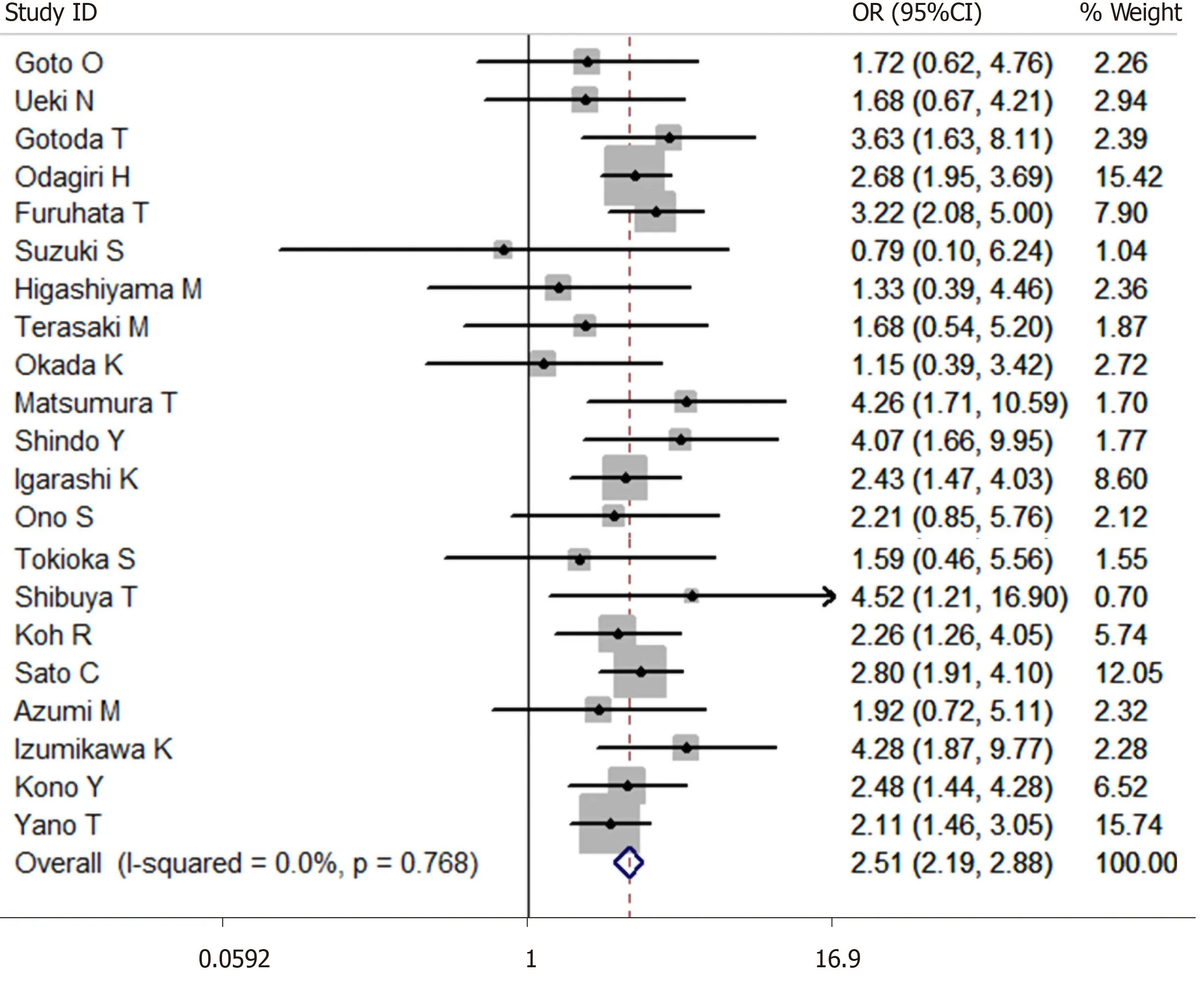

A total of 27014 cases after ESD were enrolled in this meta-analysis (3624 cases were receiving antithrombotic medication and 23390 cases were not taking antithrombotic drugs[1,6,13-30,33,37-41]). The average postoperative bleeding rate after ESD in the antithrombotic group was 13.91%, while it was 7.77% in the non-antithrombotic group. With the random-effects model, the risk of postoperative bleeding after ESD in the antithrombotic group was higher than the non-antithrombotic group (OR = 2.439, 95%CI: 1.916-3.105,P= 0.000,I2= 63.5%). Moreover, a more homogeneous analysis (I2= 0.0%) was carried out after six articles[6,20,24,26,29,36]were screened out in the sensitivity analysis and the results remained unchanged (OR = 2.507, 95%CI: 2.185-2.875,P= 0.000, Figure 3). The risk of postoperative bleeding after gastric ESD in the antithrombotic group was higher than the non-antithrombotic group (OR = 2.295, 95%CI: 1.757-2.998,P= 0.000,I2= 64.1%)[6,13-15,17,19,20,22-29,33]. Meanwhile, the risk of postoperative bleeding after colorectal ESD in the antithrombotic group was higher than the non-antithrombotic group (OR = 3.305, 95%CI: 1.561-6.998,P= 0.002,I2= 65.0%)[1,15,18,21,36].

Figure 1 A flow diagram of articles retrieved and inclusion progress through the stage of meta-analysis.

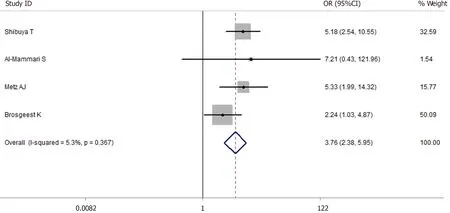

A total of 5514 cases after EMR were enrolled in this meta-analysis (1475 cases were receiving antithrombotic medication and 4039 cases were not taking any antithrombotic drugs[1,2,4,5,42]). The average postoperative bleeding rate after EMR in the antithrombotic group was 2.85%, while it was 1.29% in the nonantithrombotic group. With the random-effects model, the risk of postoperative bleeding after EMR in the antithrombotic group was higher than the nonantithrombotic group (OR = 2.688, 95%CI: 1.098-6.582,P= 0.030.I2= 72.7%). Furthermore, a more homogeneous analysis (I2= 5.3%) was carried out after one article[5]was screened out in the sensitivity analysis and the results remained unchanged (OR = 3.765, 95%CI: 2.380-5.954,P= 0.000, Figure 4). The risk of postoperative bleeding after colorectal EMR in the antithrombotic group was higher than the non-antithrombotic group (OR = 3.711, 95%CI: 2.332-5.904,P= 0.005,I2= 32.9%). But the analysis on the risk of postoperative bleeding after gastric EMR could not be carried out due to insufficient data.

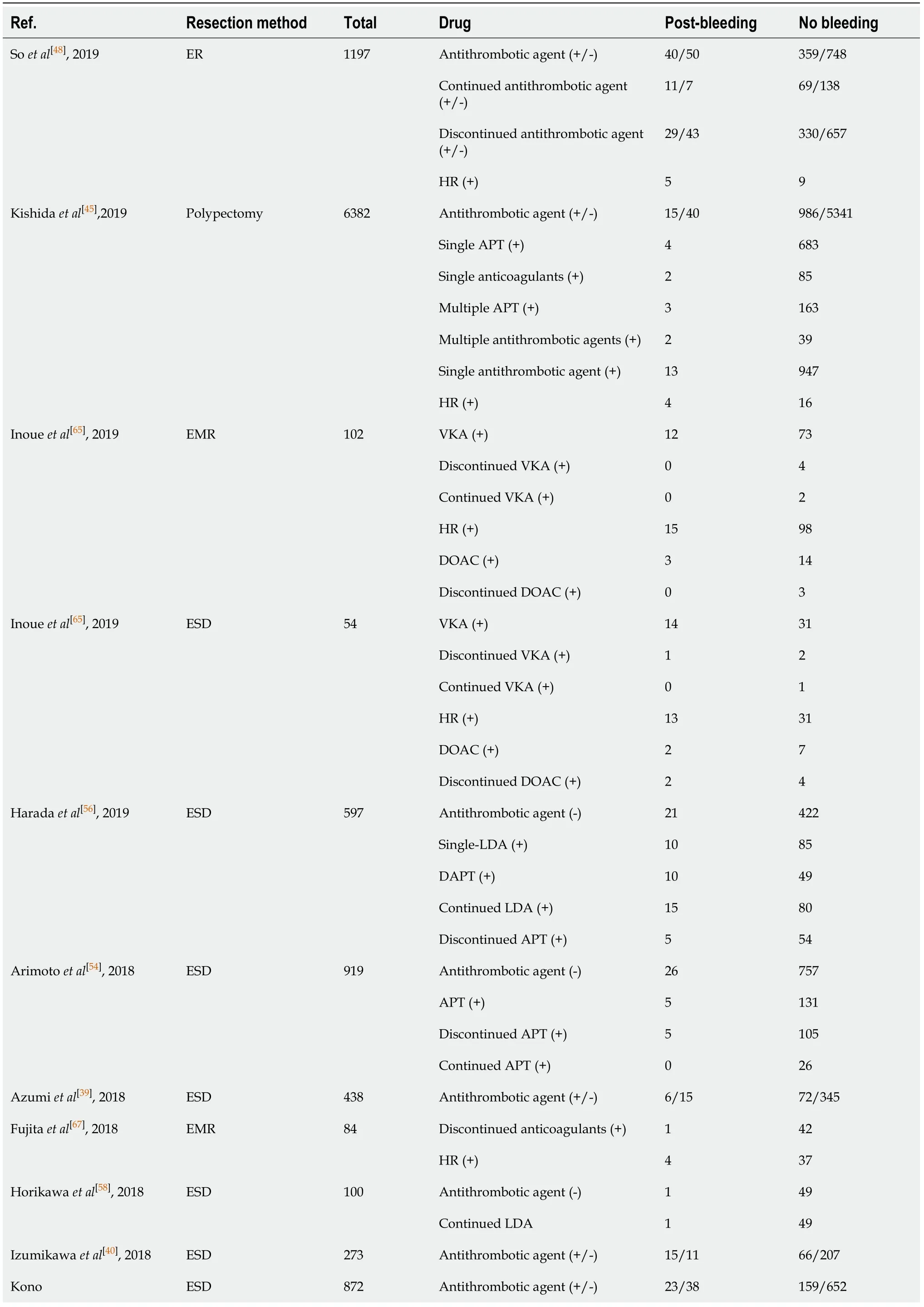

A total of 10709 cases of polypectomy were enrolled in this meta-analysis (2554 cases were receiving antithrombotic medication and 8155 cases were not taking any antithrombotic drugs[1,3,35,43-46]). The average postoperative bleeding rate in the antithrombotic group was 4.89%, while it was 1.69% in the non-antithrombotic group. With the random-effects model, there was no significant difference (OR = 2.338, 95%CI: 0.610-8.954,P= 0.215,I2= 93.6%) in the postoperative bleeding rate between the two groups. Another more homogeneous analysis (I2= 44.4%) was carried out after two articles[3,35]were screened out in the sensitivity analysis and the results were found to have changed (OR = 2.112, 95%CI: 1.434-3.112,P= 0.006, Figure 5). The risk of postoperative bleeding after colorectal polypectomy in the antithrombotic group was higher than the non-antithrombotic group (OR = 2.921, 95%CI: 1.821-4.687,P= 0.000,I2= 31.9%). Table 2 shows the number of cases with or without antithrombotic agents and hemorrhagic outcome.

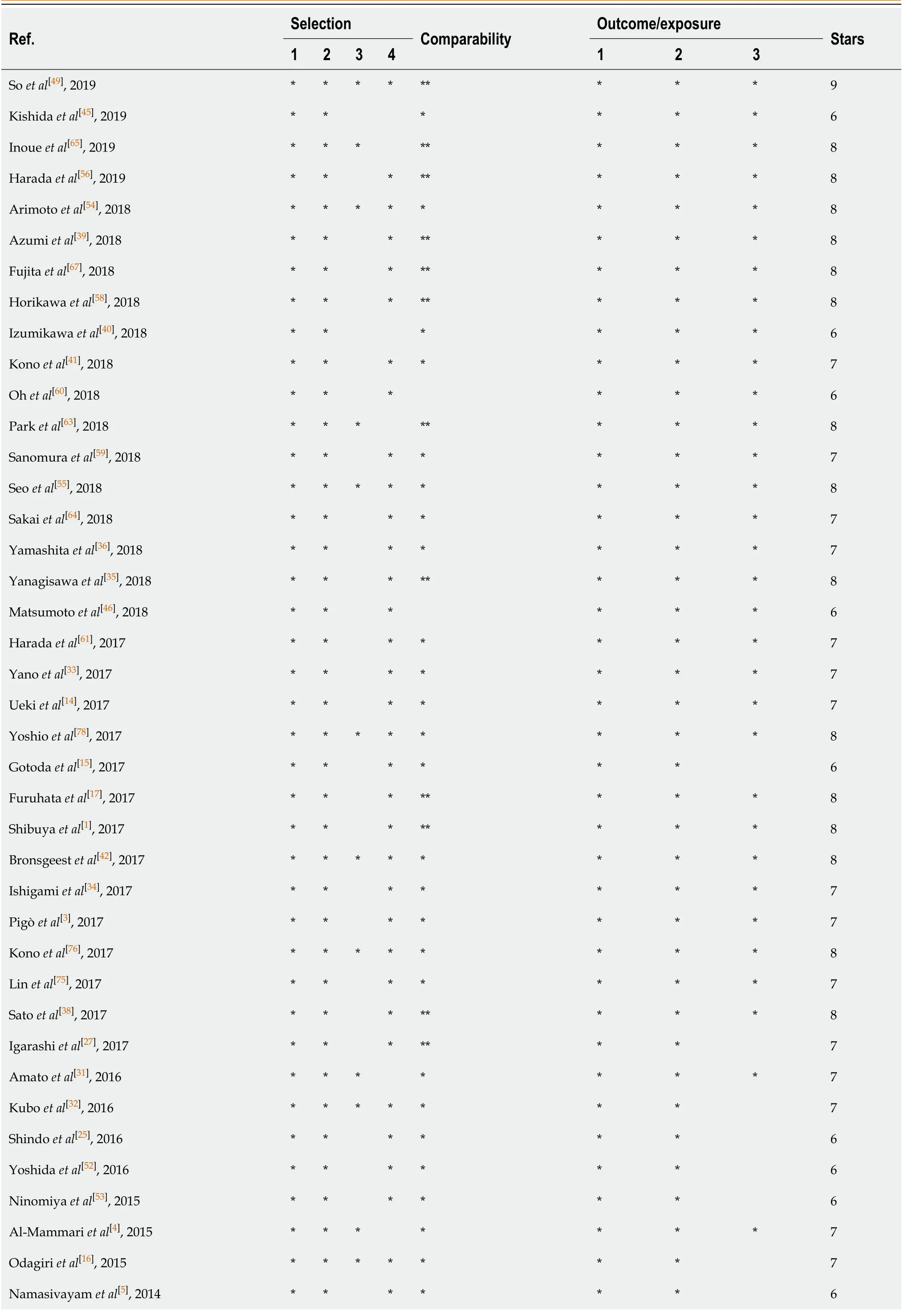

Quality assessment and publication bias

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to assess the quality of the included studies in this meta-analysis. Thirteen articles had 6 stars, twenty-three articles had 7 stars, twenty-eight articles had 8 stars, and the others had 9 stars (Table 3). At the same time, the funnel plot did not show any features associated with publication bias (Figure 6).

Subgroup analyses

Among the ESD group, we performed several subgroup analyses to independently evaluate the effects of different types of antithrombotic agents in postoperative bleeding: (1) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of singleantithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 43/524)vsnon-antithrombotic agent user (No. bleeding/total = 112/2671)[15,17,27]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in single antithrombotic agent group was significantly higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 2.061, 95%CI: 1.405-3.024,P= 0.000 (I2= 0.0%)]; (2) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of multiple antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 33/179)vsnon-antithrombotic agent user (No. bleeding/total = 150/3361)[15,17,27,41]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in multiple antithrombotic agents group was significantly higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 4.985, 95%CI: 3.251-7.561,P= 0.000 (I2= 40.6%)]; (3) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of multiple antithrombotic (No. bleeding/total = 33/179) uservssingle antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 55/666)[15,17,27,41]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in multiple antithrombotic agents group was higher than the single antithrombotic agent group [OR = 2.492, 95%CI: 1.563-3.974,P= 0.000 (I2= 43.9%)]; (4) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of discontinued antithrombotic uservs(No. bleeding/total = 81/1074) non-antithrombotic agent user (No. bleeding/total = 216/3894)[14,25,27,47-49]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in discontinued antithrombotic agent group was slightly higher than the nonantithrombotic agent group [OR = 1.405, 95%CI: 1.069-1.848,P= 0.015 (I2= 34.4%)]; (5)In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of continuous antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 18/144)vsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 50/1081)[25,27,49]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in continuous antithrombotic agent group was higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 2.886, 95%CI: 1.513-5.504,P= 0.001 (I2= 0.0%)]; (6) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of continuous antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 18/144)vsdis-continued antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 55/660)[25,27,49]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 1.615, 95%CI: 0.919-2.837,P= 0.096 (I2= 32.9%)]; (7) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of antiplatelet (APT) (No. bleeding/total = 100/891) uservsnonantithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 212/4620)[15,38,41,50,51]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in the APT agent group was higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 2.545, 95%CI: 1.979-3.273,P= 0.000 (I2= 38.8%)]. In colorectal ESD retrospective comparison studies of APT user (No. bleeding/total = 22/425)vsnonantithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 90/2914)[52-55]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in the APT agent group was higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 1.821, 95%CI: 1.127-2.944,P= 0.014 (I2= 25.8%)]; (8) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of discontinued APT user (No. bleeding/total = 17/271)vsnonantithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 127/2450)[41,51,56]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding risk between the two groups [OR = 1.218, 95%CI: 0.721-2.060,P= 0.461 (I2= 0.0%)]. In colorectal ESD retrospective comparison studies of discontinued APT user (No. bleeding/total = 9/179)vsnonantithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 69/1787)[53,54,57]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 1.494, 95%CI: 0.725-3.081,P= 0.277 (I2= 0.0%)]; (9) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of continuous APT user (No. bleeding/total = 43/350)vsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 141/2710)[25,41,51,56,58]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in continuous APT agent group was higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 2.955, 95%CI: 2.026-4.310,P= 0.000 (I2= 0.0%)]. In colorectal ESD retrospective comparison studies of continuous APT user (No. bleeding/total = 9/75)vsnonantithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 69/1787)[53,54,57]: The risk of postoperative bleeding risk in continuous APT agent group was higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 3.409, 95%CI: 1.652-7.036,P= 0.001 (I2= 43.9%)]; (10) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of continuous APT user (No. bleeding/total = 44/299)vsdiscontinued APT user (No. bleeding/total = 20/297)[41,56,59,60]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in continuous APT agent group was higher than the discontinued APT agent group [OR = 2.004, 95%CI: 1.095-3.668,P= 0.024 (I2= 0.0%)]. In colorectal ESD retrospective comparison studies of continuous APT user (No. bleeding/total = 9/75)vsdiscontinued APT user (No. bleeding/total = 9/179)[53,54,57]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 1.740, 95%CI: 0.616-4.910,P= 0.296 (I2= 50.6%)]; (11) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of multiple APT user (No. bleeding/total = 33/131)vsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 89/1815)[15,41,50,56]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in multiple APT agent group was higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 6.437, 95%CI: 4.048-10.237,P= 0.000 (I2= 7.3%)]; (12) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of multiple APT user (No. bleeding/total = 48/185)vssingle APT user (No. bleeding/total = 40/494)[15,41,50,56,60]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in multiple APT agent group was higher than the single APT agent group [OR = 3.606, 95%CI: 2.270-5.726,P= 0.000 (I2= 39.4%)]; (13) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of continuous single APT user (No. bleeding/total = 5/96)vsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 71/1262)[17,41,50,58]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 1.427, 95%CI: 0.524-3.886,P= 0.486 (I2= 0.0%)]; (14) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of aspirin user (No. bleeding/total = 38/491)vsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 145/3396): The risk of postoperative bleeding in aspirin agent group was higher than the nonantithrombotic agent group [OR = 1.889, 95%CI: 1.293-2.759,P= 0.000 (I2= 47.0%)]; (15) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of continuous aspirin user (No. bleeding/total = 36/320)vsdiscontinued aspirin user (No. bleeding/total = 34/391): There was no significant difference in the postoperative bleeding risk between the two groups [OR = 1.430, 95%CI: 0.786-2.603,P= 0.241 (I2= 0.0%)]; (16) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of discontinued aspirin user (No. bleeding/total = 31/325)vsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 147/3047)[27,51,53,56]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in discontinued aspirin agent group was higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group [OR = 2.093, 95%CI: 1.349-3.246,P= 0.001 (I2= 33.1%)]; (17) In gastric ESD retrospective compatison studies of thienopyridine derivatives user (No. bleeding/total = 0/41)vsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 123/2903)[14,15,38,50]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 0.983, 95%CI: 0.234-4.132,P= 0.981 (I2= 0.0%)]; (18) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of aspirin user (No. bleeding/total = 39/440)vsthienopyridine derivatives user (No. bleeding/total = 78/2009)[14,15,38,50,60]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in the aspirin agent group was higher than the thienopyridine derivatives agent group [OR = 1.806, 95%CI: 1.062-3.037,P= 0.029 (I2= 47.0%)]; (19) In gastric ESD comparison studies (two retrospective studies and one prospective study) of anticoagulant user (No. bleeding/total = 21/145)vsnonantithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 154/3788)[38,41,59]: The risk of postoperative bleeding [OR = 4.029, 95%CI: 2.442-6.646,P= 0.000 (I2= 18.1%)] in the anticoagulant agent group was significantly higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group; (20) In gastric ESD comparison studies (three retrospective studies and one prospective study) of warfarin user (No. bleeding/total = 24/127)vsdirect oral anticoagulants (DOAC) user (No. bleeding/total = 10/60)[38,47,59]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 0.940, 95%CI: 0.407-2.171,P= 0.885 (I2= 0.0%)]; (21) In gastrointestinal ESD retrospective comparison studies of anticoagulant user (No. bleeding/total = 13/89)vsAPT user (No. bleeding/total = 49/501)[38,41,52]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 1.677, 95%CI: 0.852-3.302,P= 0.135 (I2= 64.1%)]; (22) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of heparin replacement (HR) (No. bleeding/total = 25/128) uservsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 154/3681)[23,27,38,41]: The risk of postoperative bleeding [OR = 5.547, 95%CI: 3.457-8.900,P= 0.000 (I2= 16.9%)] in HR agent group was significantly higher than the non-antithrombotic agent group; (23) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of HR user (No. bleeding/total = 32/125)vscontinuous antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 10/101)[17,25,27,61]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in the HR agent group was significantly higher than the continuous antithrombotic agent group [OR = 2.859, 95%CI: 1.257-6.503,P= 0.012 (I2= 0.0%)]; and (24) In gastric ESD retrospective comparison studies of HR user (No. bleeding/total = 29/120)vscontinuous single APT user (No. bleeding/total = 7/83)[17,27,41]: The risk of postoperative bleeding in HR agent group was significantly higher than the continuous single APT agent group (OR = 2.988, 95%CI: 1.173-7.761,P= 0.000 (I2= 3.1%)].

Table 2 Number of cases with or without antithrombotic agents and hemorrhagic outcome

Single antithrombotic agent 12 130 Multiple antithrombotic agents (+)11 29 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (+)8 120 Discontinued Single APT (+)3 88 Multiple APT (+)3 16 Single anticoagulants (+)1 13 Continued Single APT (+)1 16 Multiple APT (+)4 2 Single anticoagulants (+)7 13 et al[41], 2018 HR (+)10 21 Single APT (+)14 147 Multiple APT (+)15 39 LDA (+)12 82 Thienopyridine (+)2 54 Continued APT (+)23 130 Oh et al[60], 2018 ESD 215 Discontinued APT (+)6 56 APT (+)12 339 Park et al[63], 2018 Polypectomy 3887 Anticoagulants (+)0 15 Antithrombotic agent (-)40 1127 Anticoagulants (+)11 65 Warfarin (+)5 32 Sanomura et al[58], 2018 ESD 1243 DOAC (+)4 14 Antithrombotic agent (-)26 945 APT (+)7 175 Aspirin (+)2 139 Warfarin (+)0 10 DOAC (+)1 2 Single antithrombotic agent (+)10 326 Multiple antithrombotic agents (+)0 23 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (+)7 206 Seo et al[55], 2018 ESD 1189 Continued antithrombotic agent (+)0 5 Discontinued anticoagulants (+)12 0 HR (+)8 70 Warfarin (+)7 55 Sakai et al[64], 2018 Polypectomy 1004 DOAC (+)1 15 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)7/18 21/652 Warfarin (+)5 14 Yamashita et al[36], 2018 ESD 650 DOAC 2 7 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)30/2 188/216 Discontinued anticoagulants (+)0 23 Yanagisawa et al[35], 2018 Polypectomy 436

Continued anticoagulants (+)10 83 HR (+)20 82 Continued warfarin (+)2 41 Continued DOAC (+)8 42 Warfarin (+)20 125 DOAC (+)10 63 Matsumoto et al[46], 2018 Polypectomy 1003 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)2/2 184/815 Continued warfarin (+)2 20 Harada et al[61], 2017 ESD 45 HR 5 18 Yano et al[33], 2017 ESD 144 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)47/103 287/1330 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)7/17 67/273 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (-)7 67 Discontinued single APT (+)4 57 Discontinued single anticoagulants (+/-)2 4 Aspirin (+)4 43 Ueki et al[14], 2017 ESD 364 Thienopyrindine (+)0 7 Warfarin (+)18 55 Yoshio et al[78], 2017 ESD 97 DOAC 5 19 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)12/14 96/407 APT (+)8 80 Single antithrombotic agent (+)6 80 Multiple antithrombotic agents (+)7 17 Single APT (+)3 69 Multiple APT (+)5 11 Warfarin (+)3 11 Aspirin (+)2 33 Gotoda et al[15], 2017 ESD 529 Thienopyridine (+)0 10 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)33/68 220/1460 Single antithrombotic agent (+)11 139 Multiple antithrombotic agents (+)6 30 Continued single APT (+)1 14 Furuhata et al[17], 2017 ESD 1781 HR (+)15 37 Shibuya et al[1], 2017 ESD 259 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)4/6 32/217 Shibuya et al[1], 2017 EMR 3018 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)16/15 510/2477 Shibuya et al[1], 2017 Polypectomy 892 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)3/5 163/721 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)13/15 107/277 APT (+)4 53 Bronsgeest et al[42], 2017 EMR Anticoagulants (+)4 43 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)10/14 35/714 Ishigami et al[34], 2017 ER 773 HR (+)10 35 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)38/32 72/467 Single APT 14 57 Pigò et al[3], 2017 Polypectomy 609

Multiple APT 3 8 HR (+)21 7 Aspirin (+)10 32 Thienopyridine 4 25 Single antithrombotic agent (+)4 24 Multiple antithrombotic agents (+)7 14 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (+)5 20 Continued antithrombotic agent (+)6 18 Kono et al[76], 2017 ESD/EMR 49 HR (+)4 12 Aspirin (+)36 3897 Lin et al[75], 2017 Polypectomy 4923 Thienopyridine (+)5 590 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)46/76 401/1855 APT (+)35 270 Anticoagulants (+)2 33 HR (+)6 33 Aspirin (+)12 199 Thienopyridine (+)0 19 Warfarin (+)1 16 Sato et al[38], 2017 ESD 2378 DOAC (+)1 17 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)35/30 332/692 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (+)26 250 Continued antithrombotic agent (+)5 49 HR 4 33 Multiple antithrombotic agents (+) 9 70 Single antithrombotic agent (+)26 262 Continued aspirin (+)4 29 Discontinue aspirin (+)19 152 Continued thienopyridine (+)1 17 Discontinued thienopyridine (+)9 63 Continued anticoagulants (+)1 11 Igarashi et al[27], 2017 ESD 976 Discontinued anticoagulants (+)3 27 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)16/16 595/2069 APT (+)11 461 Amato et al[31], 2016 ER 2692 Anticoagulants (+)5 134 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)16/13 194/565 APT (+)8 146 Anticoagulants (+)11 72 Kubo et al[32], 2016 ER 788 HR (+)10 63 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)10/13 38/201 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (+)0 25 Continued APT (+)2 8 Shindo et al[25], 2016 ESD 262

HR (+)8 5 Antithrombotic agent (-)10 585 APT (+)3 60 Yoshida et al[52], 2016 ESD 678 Anticoagulants (+)3 17 Antithrombotic agent (-)28 537 Discontinued APT (+)2 11 Ninomiya et al[53], 2015 ESD 609 Continued APT (+)5 26 Al-Mammari et al[4], 2015 EMR 117 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)1/1 14/101 Odagiri et al[16], 2015 ESD 7567 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)49/282 440/6796 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)4/10 772/912 APT (+)3 521 Anticoagulants (+)0 89 Single antithrombotic agent (+)1 617 Multiple antithrombotic agents (+)3 111 Namasivayam et al[5],2014 EMR 1712 Thienopyridine (+/-)0/10 17/912 Terasaki et al[21], 2014 ESD 363 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)4/20 36/303 Antithrombotic agent (-)16 245 Discontinued single APT (+)7 37 Continued single APT (+)2 12 Dual APT (+)11 20 Aspirin (+)9 44 Tounou et al[50], 2014 ESD 350 Thienopyridine (+)0 5 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)1/13 27/276 Suzuki et al[18], 2014 ESD 317 HR 0 6 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)10/10 77/328 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (+)2 39 Continued antithrombotic agent (+), HR (-)3 22 Matsumura et al[23], 2014 ESD 425 HR (+)5 16 APT (+)9 18 Anticoagulants (+)12 9 Aspirin (+)6 11 Beppu et al[74], 2014 ER 208 Thienopyridine (+)3 7 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (+)1 71 Inoue et al[77], 2014 Polypectomy 117 HR (+)9 36 Continued LDA (+) 1 27 Sanomura et al[66], 2014 ESD 78 Discontinued LDA (+)3 63 Antithrombotic agent (-)45 972 Discontinued antithrombotic agent (-)12 197 Yoshio et al[47], 2013 ESD 1250 HR (+)9 15 Takeuchi et al[29], 2013 ESD 833 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)21/15 69/728 Koh et al[37], 2013 ESD 1166 Antithrombotic agent (+/-)17/45 158/946

ER: Endoscopic resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection; APT: Antiplatelet; LDA: Low dose of aspirin; HR: Heparin replacement; DOAC: Direct oral anticoagulant; Thienopyridine: Thienopyridine derivatives.

Table 3 The quality assessment of included studies

Terasaki et al[21], 2014*******7 Tounou et al[50], 2014*******7 Suzuki et al[18], 2014*******7 Matsumura et al[23], 2014******6 Beppu et al[74], 2014********8 Inoue et al[77], 2014********8 Sanomura et al[66], 2014********8 Yoshio et al[47], 2013*******7 Takeuchi et al[29], 2013********8 Koh et al[37], 2013********8 Mukai et al[6], 2012******6 Lim et al[51], 2012********8 Miyahara et al[48], 2012********8 Cho et al[57], 2012********8 Toyokawa T et al[24], 2011*******7 Higashiyama et al[19], 2011*******7 Metz et al[2], 2011********8 Tokioka et al[30], 2011********8 Okada K et al[22], 2011******6 Mannen et al[20], 2010******6 Goto et al[13], 2010********8 Witt et al[44], 2009*******7 Ono et al[28], 2019*******7 Takizawa et al[26], 2008********8 Sawhney et al[62], 2007********8 Yousfi et al[43], 2004*********9

Figure 2 Forest plot of antithrombotic group vs non-antithrombotic group in endoscopic resection.

Figure 3 Forest plot of antithrombotic group vs non-antithrombotic group in endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Figure 4 Forest plot of antithrombotic group vs non-antithrombotic group in endoscopic mucosal resection.

Figure 5 Forest plot of antithrombotic group vs non-antithrombotic group in polypectomy.

Figure 6 Funnel plot of antithrombotic group vs non-antithrombotic group in endoscopic resection.

Among the EMR group, we performed several subgroup analyses to evaluate the effects of different types of antithrombotic agents on postoperative bleeding: (1) APT (No. bleeding/total = 13/605) uservsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 36/1445)[2,5,42]: OR = 1.744, 95%CI: 0.398-7.643,P= 0.461 (I2= 78.8%). There were two retrospective studies and one prospective study in the subgroup analysis. There were two studies about colorectal EMR and one study about gastric EMR in the subgroup analysis; (2) Anticoagulant user (No. bleeding/total = 44/567)vsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 218/8131)[2,5,42]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding risk between the two groups [OR = 1.409, 95%CI: 0.552-3.597,P= 0.474 (I2= 0.0%)]. There were two retrospective studies and one prospective study in the subgroup analysis. There were two studies about colorectal EMR and one study about gastric EMR in the subgroup analysis; and (3) Anticoagulant user (No. bleeding/total = 5/147)vsAPT user (No. bleeding/total = 13/605)[2,5,42]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 0.768, 95%CI: 0.261-2.261,P= 0.631 (I2= 0.0%)]. There were two retrospective studies and one prospective study in the subgroup analysis. There were two studies about colorectal EMR and one study about gastric EMR in the subgroup analysis.

Among the polypectomy group, we also performed several subgroup analyses to evaluate the effects of different types of antithrombotic agents on postoperative bleeding: (1) APT (No. bleeding/total = 56/994) uservsnon-antithrombotic user (No. bleeding/total = 121/5983)[3,43,45]: OR = 1.766, 95%CI: 1.192-2.616,P= 0.005 (I2= 73.9%) (retrospective studies). There were two studies about colorectal polypectomy and one study about gastric polypectomy in the subgroup analysis; (2) Anticoagulant user (No. bleeding/total = 16/128)vsAPT user (No. bleeding/total = 33/1106)[45,62,63]: The risk of postoperative bleeding after colorectal polypectomy in the anticoagulant agent group was significantly higher than the APT agent group [OR = 3.132, 95%CI: 1.442-6.803,P= 0.004 (I2= 9.0%)] (retrospective studies); and (3) Warfarin user (No. bleeding/total = 32/226)vsDOAC (No. bleeding/total = 13/98)[35,36,64]: There was no significant difference in the risk of postoperative bleeding between the two groups [OR = 1.126, 95%CI: 0.557-2.275,P= 0.741 (I2= 0.0%)] (retrospective studies). There were two studies about colorectal polypectomy and one study about gastric polypectomy in the subgroup analysis.

A subgroup analysis was planned to assess the risk of postoperative bleeding according to the difference in the size of the lesion, dosage and cessation period of antithrombotic agent, but we failed to perform the analysis because of insufficient data.

Thromboembolic event

Thromboembolic event is defined as arterial thromboembolism. This includes stroke, transient ischemic attack and infarction perioperative period. These thromboembolic events in included studies were available in nineteen articles (one event in the heparin therapy group[17], five events in the antithrombotic group[5,27], three events in the HR group[35,47,64], one event in the discontinued anticoagulant therapy group[30], one event in the discontinued antithrombotic therapy group[32], two events in the withdrawal period of antiplatelet therapy group[2,51], one event in the anticoagulant therapy group[44], one event in the withdrawal period of anti-vitamin K antagonisis therapy group[65], four events in the low dose aspirin interrupted group[66]). No thromboembolic events occurred in seven studies[36,41,49,58,59,67].

DISCUSSION

Despite several practice guidelines about the cessation or continuation of antithrombotic drugs before ER made by the British Society of Gastroenterology[68], the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy[68], the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy[69]and the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society[70], the effect of antithrombotic drugs on the risk of postoperative bleeding was still controversial in some studies[4,6,13,14,16,19-22,24,26,27,31,37,48,57]. Our study found that antithrombotic agents confer a higher risk for postoperative bleeding after ESD and EMR. But the risk of postoperative bleeding after polypectomy was not significantly elevated in the patients with antithrombotic drugs from our study, which was in consistent with the results of a study by Matsumotoet al[46]. Nevertheless, there was significant heterogeneity in the analysis of antithrombotic groupvsnonantithrombotic group. To explain the heterogeneity (I2= 82.5%) of our meta-analysis, we got the following findings: (1) Different methods were used to prevent postoperative bleeding; (2) Different definitions on postoperative bleeding[2,19]; (3) Different types and doses of antithrombotic agents; and (4) Different follow-up time, ranging 24 h to 3 mo. In order to reduce the heterogeneity, we have done the subgroup analyses to assess the effect of different types of antithrombotic agents in the risk of postoperative bleeding.

Some studies found that APT did not correlate with the risk of postoperative bleeding[32,52]. At the same time, the risk of delayed postoperative bleeding after ESD was not increased in a single APT agent (continued or discontinued)[17]. In contrast, it has been demonstrated that APT (especially dual APT) increases the risk of postoperative bleeding[50]. A retrospective study by Singhet al[71]showed that clopidogrel alone was not an independent risk factor for postoperative bleeding, but a randomized trial by Chanet al[72]showed that continued clopidogrel use results in a higher risk of postoperative bleeding compared to the discontinued clopidigrel use group. Our study found that continued single APT agent use did not increase the risk of postoperative bleeding, but multiple APT agents increased the risk of postoperative bleeding after ER.

Some studies found that low dose aspirin and continued use of aspirin didn’t induce a higher risk of postoperative bleeding after polypectomy and gastric ESD[23,43,50]. However, Ninomiyaet al[53]found that continued use of aspirin increased the risk of postoperative bleeding after colorectal ESD. A study by Metzet al[2]demonstrated that the use of aspirin within 7 d of the operation was an independent risk factor for postoperative bleeding after colonic EMR. In a meta-analysis by Shalmanet al[73], the risk of immediate bleeding in patients with aspirin was not increased, but the risk of delayed bleeding in patients with aspirin or thienopyridine derivatives was increased. Our study found that the use of aspirin significantly increased the risk of postoperative bleeding, but thienopyridine derivatives did not increase the risk of postoperative bleeding after ER. Nevertheless, the guidelines recommend continuing aspirin and withdrawing thienopyridine derivatives in the endoscopic resection[68-70]. Therefore, more prospective or randomized controlled trials are needed to determine the effects of aspirin and thienopyridine on the risk of postoperative bleeding after ER.

Several guidelines about gastroenterological endoscopy recommend that anticoagulant agent should be discontinued with HR[68-70]. APT plus HR (meaning that anticoagulants were substituted by heparin before polypectomy) were not correlated with postoperative bleeding, but anticoagulant or anticoagulant plus HR were risk factors for postoperative bleeding[32]. Besides, HR alone was related to postoperative bleeding in univariate analysis but was not in multivariate analysis[32]. And our study has reached the same conclusion. Cessation of antithrombotic therapy could result in thromboembolic events such as cerebral infarction and hemorrhagic shock. But the risk of the thromboembolic events in the included studies is relatively low.

There were several drawbacks in this meta-analysis. First of all, the results of our meta-analysis were derived from retrospective studies. Retrospective studies may underestimate the risk of postoperative bleeding. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm our results. Secondly, the surveillance periods of included studies were not exactly the same. Finally, different types and doses of antithrombotic agents were used in the included studies, which may lead to bias.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the risk of postoperative bleeding after ER (polypectomy, EMR and ESD) correlated with the types and management of the antithrombotic agents according to our meta-analysis. Interrupting or switching antithrombotic therapy might result in the increased risk of serious thromboembolic events. Therefore, it is important to comprehensively assess the risk of postoperative bleeding and thromboembolic events in the patients with antithrombotic drugs after ER.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Endoscopic resection (ER) is deemed as an effective method for gastrointestinal neoplasia, polyp, gastric adenomas, early oesophageal, gastric and colorectal cancer.More and more people suffering from cardiovascular disease and/or cerebrovascular disease receive antithrombotic therapy which change patients’ coagulation status and may lead to high risk of postoperative bleeding after ER. The relationship between the postoperative bleeding af ter ER and antithrombotic agents is still uncertain.

Research motivation

This study explored the relationship between the postoperative bleeding after ER and antithrombotic agents.

Research objectives

The aim of this study is to identify whether the use of antithrombotic drugs increases the risk of the postoperative bleeding after ER by a systematic review and metaanalysis.

Research methods

A systematic search was conducted on PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane library. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to evaluate the quality of studies. Stata 12.0 was used for statistical analysis. The odds ratio and 95%CI were calculated and heterogeneity was quantified using Cochran’s Q test and I2.

Research results

Total 66 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Pooled data suggested that antithrombotic therapy was significantly associated with postoperative bleeding after ER. The risk of postoperative bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic mucosal resection and polypectomy in the antithrombotic group was higher than the non-antithrombotic group.

Research conclusions

The risk of postoperative bleeding after ER correlated with the types and management of antithrombotic agents by our meta-analysis.

Research perspectives

Our results can guide the use of antithrombotic drugs before ER and evaluate the risk of postoperative bleeding.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年5期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年5期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Comparing the incidence of major cardiovascular events and severe microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Implications of COVID-19 for inflammatory bowel disease: Opportunities and challenges amidst the pandemic

- Current trend in the diagnosis and management of malignant pheochromocytoma: Clinical and prognostic factors

- Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of COVID-19 infection: Lessons for practitioners