Implications of COVID-19 for inflammatory bowel disease: Opportunities and challenges amidst the pandemic

Maliha Naseer, Shiva Poola,Francis E Dailey, Hakan Akin, Veysel Tahan

Maliha Naseer, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834, United States

Shiva Poola, Department of Internal Medicine/Pediatrics, Brody School of Medicine/Vidant Medical Center, Greenville, NC 27834, United States

Francis E Dailey, Hakan Akin, Veysel Tahan, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States

Abstract

Key Words: SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; Inflammatory bowel disease; Crohn’s disease; Ulcerative colitis; Pandemic

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), also known as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, is a global health emergency with major public health concerns[1]. SARS-COV is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus Betacoronavirus and subgenus Sarbecoronavirus and recognized to cause severe acute respiratory syndrome for two decades. SARS-CoV is an emerging zoonotic disease that has the potential to infect humans, bats, and other mammals. There are hundreds of strains of the coronaviruses and over the last two decades different strains have caused three major documented epidemics globally, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality[2]. The current pandemic began at the end of 2019 as a cluster of new atypical pneumonia cases from an unknown cause, traced back to a wet animal market in the city of Wuhan, in the Hubei province in China. On December 31, 2019, the outbreak was reported to the WHO regional office in China and was linked to a novel strain of a coronavirus provisionally named as 2019-nCoV[3]. It was later designated as SARS-CoV-2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses[4]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus rapidly spread in the entire world. As of October 9, 2020, there have been 36754395 confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 have been documented in over 187 countries and territories with a global death toll of 1064838. The first case of SARS-CoV-2 was reported in the United States of America (USA) on January 20, 2020, and since then the number of confirmed cases has been increased dramatically[5]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report from the USA, the overall cumulative hospitalization rate is 183.2 per 100000, with the highest rates in people 65 years and older (495.5 per 100000) and 50-64 years (273.2 per 100000)[6]. Other high risk groups for severe infection and hospital admission include male gender, smokers, residents at nursing home or long term care facilities, and people of all ages with pre-existing medical illness,e.g.hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, chronic lung/liver/heart disease, chronic kidney disease undergoing dialysis, and immunocompromised or immunosuppressed patients[7].

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) which includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) is chronic remitting and relapsing disorders with intestinal and extraintestinal manifestation[8]. Globally, there are 6.8 million cases of IBD, and the agestandardized prevalence rate increased from 79.5/100000 population to 84.3/100000 population between 1990-2017[9]. There is evidence from translation research that angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and TMPRS2 receptors are exhibited in abundance in the ileum and colon[10]which leads to the hypothesis that patients with CD and UC are more at risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its complications than the general public. Furthermore, patients with IBD are usually malnourished and often treated with immunomodulators and immunosuppressive medications to control inflammation and to prevent relapse and complications. These medications are known to be associated with opportunistic infections, particularly viral infections such as influenza and herpes zoster, reactivation of chronic hepatitis B with anti-tumor necrosis factors (anti-TNFs), and viral warts associated with the use of thiopurines[11]. In addition, frequent encounters with health care facilities for infusion of the biologics, follow up visits, blood draws and endoscopies put these patients at risk for exposure to SARSCoV-2 infection. As a result, there is a concern among healthcare providers and patients that having IBD (quiescent or active) and being on medical therapies to control inflammation places them at a substantial risk to contract SAR-CoV-2 infection and progress to a more critical illness requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission, ventilator use, and have increased mortality compared with the general population. However, there is strong evidence that having inflammatory bowel disease is not a risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection[12]. The management of IBD is complex, multifaceted and there are numerous questions and concerns related to IBD and COVID-19. The purpose of this review article is to summarize the growing level of evidence and understanding of the management of IBD during the COVID-19 pandemic, in the light of international and national gastroenterology society guidelines. To fulfil the objectives of the review, we did thorough literature search on PubMed, OVID and EMBASE through December 2019 to October 2020.

PRESENTATION, CHARACTERITICS AND RISK FACTORS OF SEVERE COVID-19 INFECTION IN IBD PATIENTS

The current literature suggests that digestive symptoms such as non-bloody diarrhea, nausea and vomiting are commonly exhibited by COVID-19 patients with a variable frequency of 11%-35%[13,14]. Nobelet al[15]published a case control study involving twohundred and seventy-eight SARS-CoV-2 patients. According to the study results, patients with diarrhea, nausea and vomiting at the time of diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 were 70% more likely to be tested positive for COVID-19 infection than other patients. Another retrospective cross-sectional study which included 207 consecutive patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 showed that the presence of digestive symptoms was associated with a higher severity of overall illness and the need of hospitalization. However, no significant differences were reported in ICU admissions, ventilator use and mortality in patients with predominantly gastrointestinal symptoms[16]. It is also now well established that there is fecal shedding of the coronavirus as detected by nucleic acid in more than 50% of patients’ stool samples and persists even after nasopharyngeal samples becomes negative[17]. Recently, a case of a female patient with COVID-19 infection presenting as bloody diarrhea was published by Carvalhoet al[18]Her evaluation was significant for leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein and evidence of colitis on computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen. With the presumed diagnosis of infectious colitis and to rule out inflammatory and ischemic colitis, a flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed which showed erythema without ulceration in the distal colon. Biopsies were negative for infectious colitis, ischemia, or inflammatory bowel disease. On day 4 of hospitalization, SARS-CoV-2 PCR from nasopharyngeal swab turned positive[18]. The clinical implication of these gastrointestinal symptoms is important especially in patients with IBD. Patients with IBD having new or worsening gastrointestinal symptoms with and without respiratory symptoms should be thoroughly evaluated using appropriate testing and non-invasive measure such as inflammatory markers, fecal calprotectin and imaging studies to differentiate acute flare with SARS-CoV-2 infection. In a systematic review published by D’Amicoet al[19], the prevalence of COVID-19 in IBD cohort was found to be 0.4%. They included 23 studies and found more prevalence of COVID-19 infection in male patient with inflammatory bowel disease regardless of their age[19].

Patients with CD and UC are often immunosuppressed. However, the exact impact of the degree of immunosuppression on the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection is not known. It is also not certain if untreated or partially treated IBD increases the risk of getting SARS-CoV-2. Preliminary data of risk and characteristics of corona virus infections in IBD patients from the first epicenter i.e. Wuhan, China is scarce. A study published by Anet al[20]included 318 patients with IBD registered between Jan 1, 2000, and Dec 8, 2019, in a prospective database were followed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with IBD were contacted and educated about self-prevention measures such as hand hygiene, keeping track of pulmonary symptoms and fever and to seek medical assistance onlinevsin person. In addition, infliximab infusions and other immunosuppressive treatments were discontinued as per guidelines of the National Chinese Society of Gastroenterology[20]. In contrary, clinicians from Italy published their experience of managing seventy-nine patients with IBD who tested positive for COVID-19 from 24 referral IBD units from March 11thto 29th, 2020. Of these patients, 28% of those with IBD and COVID-19 positive were hospitalized and another 6% were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection when they were admitted to the hospital with IBD flares. After controlling for confounding factors, age more than 65 years, diagnosis of UC, IBD activity and Charlson Comorbidity Index > 1 were significantly associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization. In this study, the authors found no relation of IBD treatments with COVID-19 infection severity[21].

More recently, an international registry/database was developed called the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion (SECURE)-IBD to report adult and pediatric SARS-CoV-2 cases and its outcome in terms outpatient managementvshospitalization, ICU admission, ventilator use and mortality in IBD patients. As of October 10, 2020, 2575 cases of IBD disease with concurrent COVID-19 patients were reported to the registry worldwide. Preliminary analysis of this database showed that young (under 40 years) IBD patients with COVID-19 infection were more likely to exhibit a milder form of disease and approximately 80% were managed in the outpatient setting. There is a direct correlation of increasing age with more severe pneumonia requiring hospitalization, ICU admission and ventilator use. Approximately 25% of the deaths were reported in the older IBD patienti.e.≥ 80 years which is highest among all age groups. Furthermore, 54% of male IBD and COVID-19-positive patients needed hospital admission, and 5% developed severe respiratory disease as defined by ICU admission, ventilator use or even death. A total of 1447 patients with CD developed COVID-19 infection, and 78% of them were managed in the outpatient; of those with UC and COVID-19-positive, 70% were managed as outpatients. Those with UC were also more likely to develop severe disease, be admitted to the ICU, and require ventilator support. In terms of disease activity, IBD patients in remission who developed COVID-19 infection were more likely to develop a milder form of the viral illness, while those with moderate-to severe activity tended to be hospitalized and require ICU admission. Similarly, having multiple comorbid conditions was shown to be a risk factor for developing severe COVID-19 infection in those with underlying IBD[22].

MANAGEMENT OF IBD MEDICATIONS DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

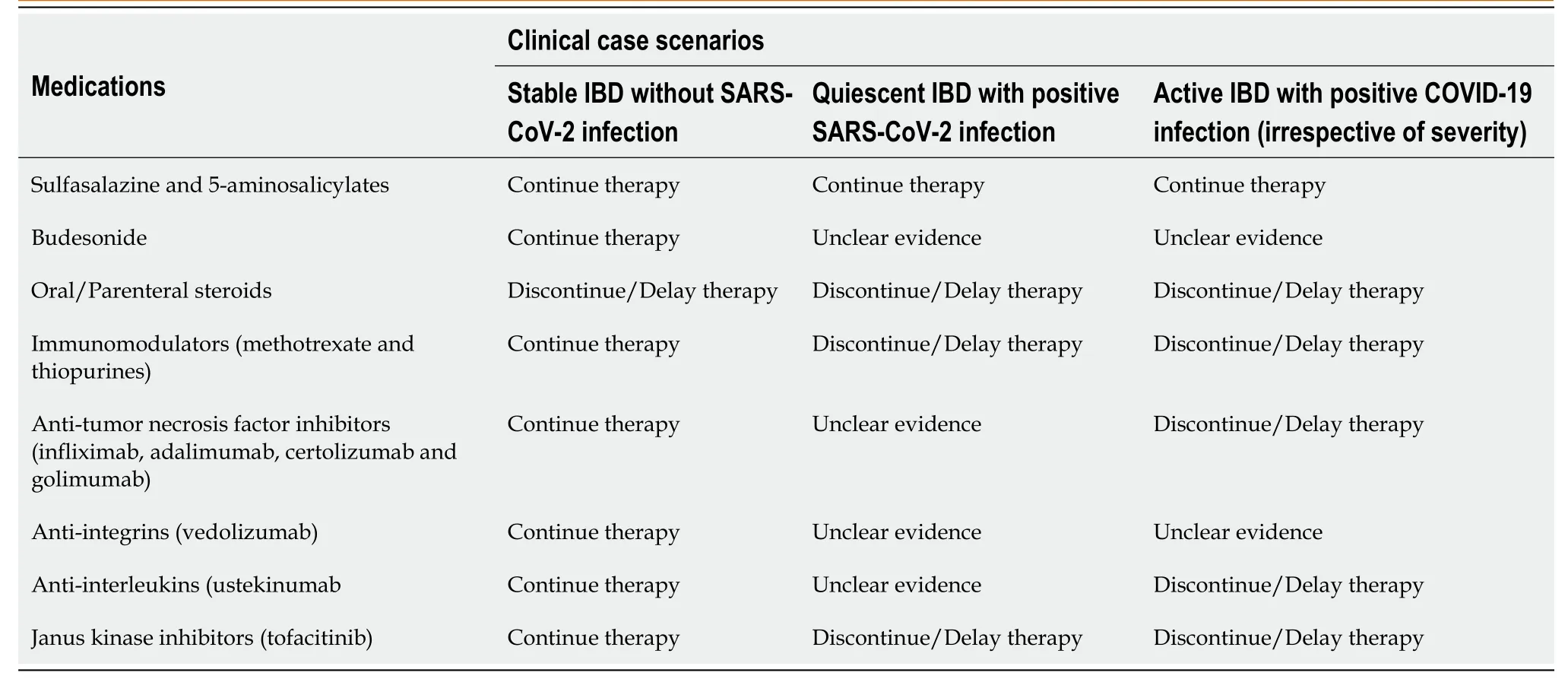

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA), the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO), and the International Organization for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IOIBD), recommend against discontinuation of immunosuppressive and biological drugs as a preventative strategy in IBD patients without symptoms and signs suggestive of COVID-19 infection[23-25]. In this section, we will discuss the safety of the medications (immunomodulators and immunosuppressive) in stable IBD patients without COVID-19 infection (Table 1).

Sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylates

Sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASA) are mild immunosuppressive medications and are often used as initial therapy for induction and maintenance of mild to moderate UC[26]. Overall, they are safe, effective and tolerated well. Preliminary data from the SECURE-IBD registry showed about 14% of IBD and COVID-positive patients on sulfasalazine and 5-ASA compounds developed severe infection (ICU/Ventilator/Death)[22]. However, the data should be interpreted with caution as the medication categories were not mutually exclusive. In summary, sulfasalazine and 5-ASA are considered safe even during the COVID-19 pandemic and should be continued.

Table 1 Management of inflammatory bowel disease medications during the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are often used as a first-line treatment in IBD as an initial treatment to induce remission and management of acute flares. Prolonged use of steroids is associated with immunosuppression, opportunistic infections and increased mortality in IBD patients[27]. Due to these immunosuppressive and its anti-inflammatory properties, systemic steroids have been evaluated in multiple randomized clinical trials and found to be promising in the management of severe and critically ill COVID-19 cases[28,29]. There is a recent prospective meta-analysis by the World Health Organization REACTi.e., Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies Working Group. The meta-analysis included data from 7 clinical trials involving more than 1700 COVID-19 patients and concluded that corticosteroids has mortality benefits[30]. Though there is limited information on the use of steroids in COVID-positive IBD patients, the present evidence linked the concurrent steroid use to increased rates of hospitalization and severe COVID-19 infection in IBD patients[22,23].

Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators such as methotrexate and thiopurines (azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine) are found to be effective as monotherapy and in combination therapy for IBD patients. Though immunomodulators are usually safe, their use has been associated with lymphopenia (which is associated with a poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients) and opportunistic viral infections such as herpes simplex and viral warts[31].In vitrostudies suggest that thiopurines have potential antiviral activity against SARSCoV or MERS-CoV, but these results were not reproduced in humans[32]. Methotrexate and thiopurines are safe and should be continued in stable IBD patients without a COVID-19 infection. According to the SECURE-IBD registry data, methotrexate and thiopurines are associated with a severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in 10%-11% of IBD patients. Gastroenterologists can consider discontinuing immunomo-dulators in IBD patients with suspected and confirmed COVID-19 infections[22].

Biologics

Biologics such as anti-TNF agents (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab and golimumab), anti-integrin (vedolizumab) and anti-interleukin-12/23 biologics (ustekinumab) are safe and effective treatment modalities for moderate-to-severe CD and UC[33]. With anti-TNF therapy, there are risks of opportunistic viral infections, reactivation of hepatitis B infection, and latent tuberculosis[34]. According to current recommendations, biologics should be continued in stable IBD patient without COVID-19 infection to prevent acute flares and immunogenicity. However, the clinician can consider holding biological therapy for 2 weeks or more if an IBD patient is exposed to COVID-19 and discontinued if patients have an active COVID-19 infection until the patient clears the infection[35].

Tofacitinib, an oral JAK inhibitor, is approved for the management of UC. According to expert opinion, tofacitinib should be continued in the lowest possible dose to maintain remission. Patients on tofacitinib in contact with someone positive for COVID-19 should consider temporarily withholding the medication for two weeks. In patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection, consideration for discontinuation of tofacitinib should be made until the patient clears the infection[31].

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MEASURES—PREVENTION OF COVID-19 INFECTION IN IBD PATIENTS

Emerging data reveals that patients with IBD are not at higher risk of a COVID-19 infection, and like the general population, should follow universal precautions to prevent infection. Current guidelines, expert opinion, and lessons learned from experience of epicenters such as Wuhan, China, Milan, Italy, New York City, USA and more recently Brazil, highlight the importance of patient education regarding selfprevention measures, minimizing contact with health care facilities through telemedicine, and ensuring continuation of IBD medicines to prevent COVID-19 infection and IBD flare[12,36-38].

Health optimization and malnutrition

Nutrition is an important determinant of health and malnutrition is established to be associated with multiple negative health outcomes in general. This is also true in the case of a COVID-19 infection[39]. Data from China and North America show that COVID-19 infections tend to be more severe (defined as the need for hospitalization, ICU admission, and ventilator use) and with higher mortality in the elderly, patients with underlying health conditions, and the malnourished[40]. Older age and co-morbid conditions are independently associated with sarcopenia (reduced muscle mass) and hypoalbuminemia. Patients with IBD are often malnourished due to their symptoms and medications such as steroids, sulfasalazine and methotrexate[41]. Optimization of nutritional status can prevent severe COVID-19 infections. IBD patients should continue mineral and vitamin supplementation and avoid smoking and foods that can trigger flares[42].

Minimize risk of COVID-19 infection

So far, the best preventive strategy to avoid COVID-19 is by minimizing the risk of exposure to the virus. This can be achieved by following universal precautions and avoiding contact with healthcare facilities.

Reduce the risk of transmission

All IBD patients must be educated about preventive strategies to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the WHO guidelines, the general population including patients with IBD should clean their hands with an alcohol-based hand sanitizer or wash with soap and water regularly and thoroughly, maintain social distance of at least 3 feet, avoid going to crowded spaces, public toilets, touching the face/eyes/nose/mouth, cancel non-essential travel, follow good respiratory hygiene (i.e., cover sneeze and cough), and to seek appropriate medical attention if symptoms develop suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection[43,44].

Immunization

IBD patients are at risk of vaccine-preventable viral and bacterial infections. They should be encouraged to receive pneumococcal (PCV13 and PPSV 23) and influenza vaccines to prevent co-infections[12].

Avoid exposure to health care facilities-Role of telemedicine services

To prevent spread of the COVID-19 infection, IBD patients and physicians are encouraged to use telemedicine to avoid unnecessary exposure to COVID-19. Telemedicine is defined by the Institute of Medicine as the use of electronic and telecommunications technology to provide and support healthcare when distance separates the participants[45]. Prior to COVID-19, the utilization of telemedicine in North America was limited due to several reasons which included low reimbursements from insurance companies, lack of training, unavailability of the equipment, software constraints, and other technical issues[46]. Telemedicine services are found to be useful for patient monitoring, advice, and education during this unprecedented time and has been adopted by health systems globally[47,48]. Similarly, in the United States the use of telemedicine services is tremendously expanded due to improved reimbursements from insurance companies and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Prevention of COVID-19 at infusion centers

To prevent the risk of flares and immunogenicity, IBD patients should continue with their infusions at scheduled times. However, patients and infusion center management should take measures to reduce the risk of coronavirus transmission. Examples of these measures include implementation of pre-admission screening protocols to assess for the symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection, preferably 1-2 days before their scheduled infusions. On the day of infusion, patients should use designated entry points to avoid contact with hospitalized patients[49]. No accompanying persons should be allowed in the infusion center. Patients with IBD should be re-screened for COVID-19 symptoms with temperature measurement on the day of infusion. All patients and staff should wear surgical masks with rearrangement of seats approximately 1.5 m apart[50].

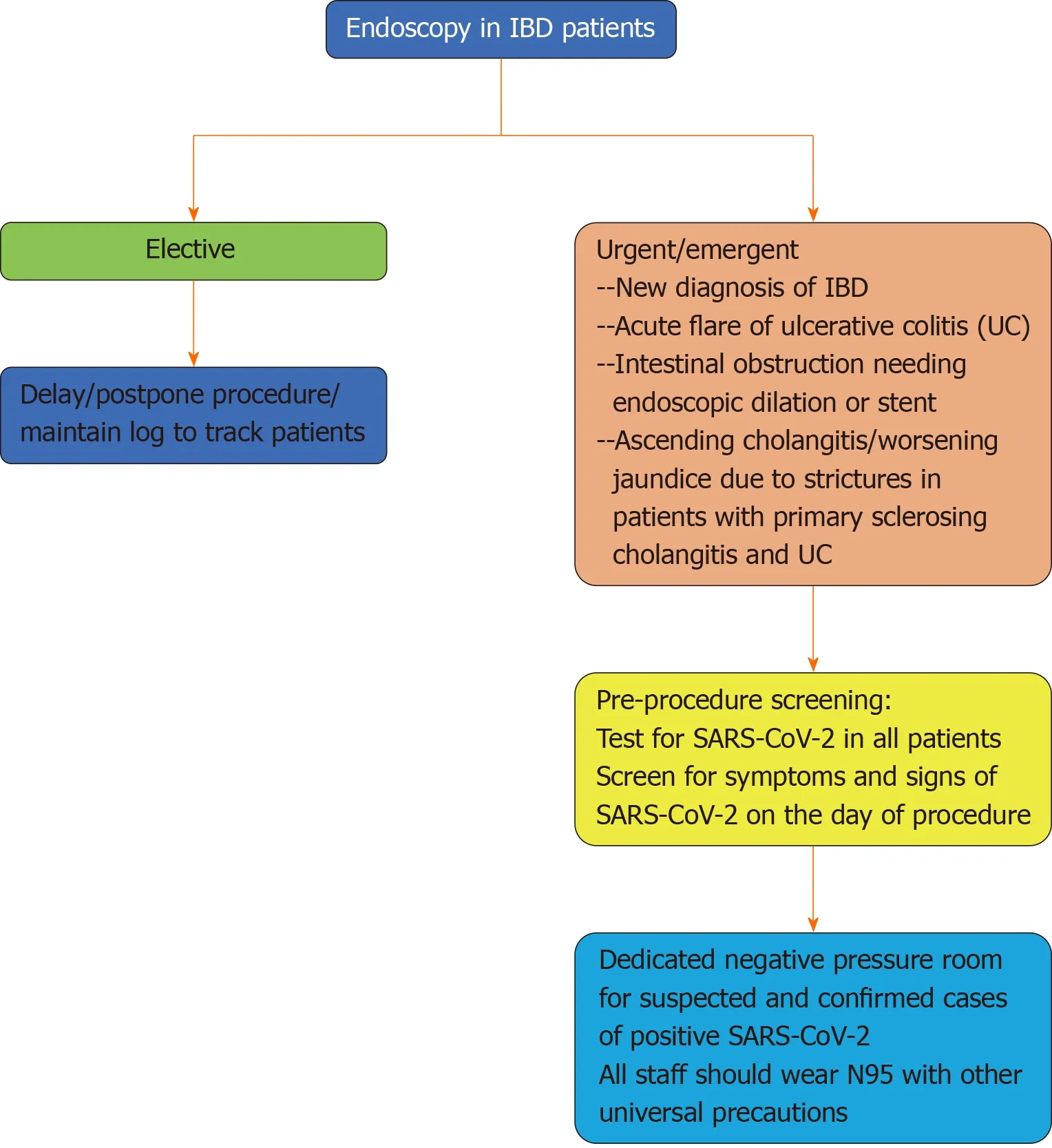

ENDOSCOPY IN IBD PATIENTS DURING THE PANDEMIC

Due to the risk of community transmission from infected aerosols and potential fecal shedding of the SARS-CoV-2, endoscopies should be scheduled in carefully selected patients after weighing the risks and benefits. Currently, only urgent and emergent endoscopic procedures are recommended by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG), the IOIBD, the ECCO, and the CCFA to avoid potential exposure of SARS-CoV-2 to health care personnel and patients[23,35,51](Figure 1). However, it is not clear when to consider endoscopy as urgent or emergent in patients with IBD. Iacucciet al[52]published a review articles inLancet Gastroenterology and Hepatologyto discuss four different scenarios that could justify the need for endoscopic evaluation (diagnostic and therapeutic) during the pandemic. In the first scenario, the authors discussed a case of a suspected new diagnosis of IBD with possible moderate-to-high degree of inflammation as evident by elevated inflammatory markers and fecal calprotectin. In this particular scenario, flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy with random biopsies were recommended before initiating biologics. Other indications for urgent endoscopy for IBD patients include acute flare of UC, especially if the last endoscopic procedure was more than 3 months ago, partial bowel obstruction in patients with IBD needing urgent endoscopic decompression or stent placement, and ascending cholangitis or worsening jaundice in patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis and IBD requiring endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with stent placement[52].

All IBD patients needing endoscopic procedures should be tested for COVID-19. Suspected and confirmed cases should be performed in a negative-pressure room and health care providers should follow standardized precautions including hand hygiene and use of disposable gowns, N95 mask with surgical mask, gloves, and head and shoe covers. In addition, the American and European gastrointestinal societies (ASGE and ESGE) published guidelines for infection control and scope reprocessing during the COVID-19 pandemic. After procedures, the endoscope should be placed in a fully enclosed and labeled container for transportation to the decontamination room. The reprocessing staff should also wear adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) to limit their exposure. Commonly used disinfectant (bactericidal, mycobactericidal, fungicidal and viricidal) can be used to clean scopes after procedures and no special handling instruction are recommended. Meticulous attention should be paid to clean the procedure room after each procedure and at the end of the day[53-55].

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH IBD DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Over the past decade, significant advances have been made in the medical management of IBD. However, timely surgery remains a vital part in the current multi-modal approach to manage both CD and UC and their complications. According to the estimates about half the patients with UC and up to two-third of people with CD will eventually require surgery[56]. Surgery in IBD patients can be performed electively,e.g.to eliminate risk of cancer and management of medical refractory IBD, or emergently, such as in cases of intestinal perforation, toxic megacolon, strictures, fistulas and abscesses[57].

Figure 1 Simplified algorithm for endoscopic management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Surgical management of IBD poses unique challenge during the current pandemic, especially in the timing of the surgery. Poor outcomes after elective surgery in COVID-19 patients were reported in a study published by Leiet al[58]. In this retrospective analysis, 34 patients who underwent unintentional elective surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 were included. All patients developed pneumonia from SARS-CoV-2 infection shortly after their procedure, approximately 44% of patients needed ICU admission, and 20.5% of patients died from complications such as adult respiratory distress syndromes, arrythmias and cardiac arrest. Patients with active IBD or in remission are susceptible to COVID-19 and the possibility of increased post-operative morbidity and mortality is an important factor to consider for scheduling non-emergent and elective procedures. In addition, there is always a risk of staff exposure from suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients during the perioperative period and nosocomial transmission to other patients[59]. Therefore, the CCFA, ECCO, IOIBD, and BSG recommend reducing contact in the healthcare settings by delaying elective non-essential endoscopies and surgical procedures to reduce possible exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection and to conserve scarce resources in this time of uncertainty[23,35,51]. However, delays in IBD surgeries caused by COVID-19 pandemic can exert tremendous pressure on an already strained healthcare system, harm to IBD patients, and causes anxiety for patients and families.

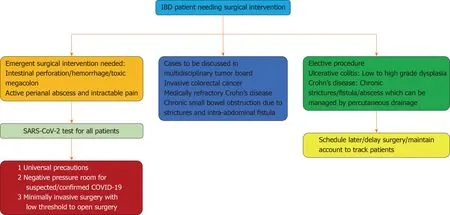

In April 2020, the IOIBD and American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons developed expert-based recommendations for the surgical management of IBD patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the recommendations, the perioperative considerations includes testing all IBD patients requiring surgery for SARSCoV-2 preoperatively due to the high risk of transmission from asymptomatic and presymptomatic COVID-19 infected patients and carriers. In addition, the experts recommend practicing universal precautions peri-operatively due to questionable reliability of the test, wide variations in the sensitivity and specificity resulting in high false positives and shedding of the virus through aerosol and fecal-oral route in asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic patients. To prevent nosocomial transmission, all staff should wear PPE such as N95 masks covered by surgical masks and plastic face shields. The surgeries should be performed in negative-pressure rooms on suspected and confirmed COVID-19 patients with IBD[60](Figure 2).

Figure 2 Simplified algorithm for surgical management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF CD

Patients with CD often need operative interventions to alleviate symptoms of severe inflammation in the intestine, treat complications such as intestinal hemorrhage, perforation, abscess formation, fistulas, strictures and to improve quality of life. Per experts’ recommendations, indications for emergent surgical interventions in patient with CD during the COVID-19 pandemic includes medically unstable patient with active intestinal hemorrhage not amenable to or failure to controlled by angiography, acute small bowel obstruction, perforation, peritonitis or abscess not responding to percutaneous drainage and antibiotics. Small bowel obstruction and contained perforation in otherwise stable patients can be managed non-operatively and surgery is reserved for people who fail to respond conservative treatment. Invasive small bowel and colon cancer should be discussed in tumor board and scheduled for procedure promptly. Cases of medically refractory CD, chronic small bowel obstruction due to strictures, and intra-abdominal fistula should be discussed in multidisciplinary team meetings and should prioritize these patients once surgical slots become available. Regarding perianal CD patient with active perianal abscess, intractable pain, and sepsis not responding to minimally invasive surgical methods and broad-spectrum antibiotics should also be scheduled for fecal diversion surgery urgently.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF UC

Medical refractory disease and complications of severe UC such as intestinal hemorrhage, perforation and toxic megacolon are indications for emergent laparotomy and surgery should not be delayed. Invasive colorectal cancer with and without metastatic disease should be discussed in multi-disciplinary tumor board meetings and should be treated promptly. Surgeries for patients with UC with low-grade to high-grade dysplasia may be delayed in the short term and surgeons should maintain records of the deferred procedures to schedule them once slots are available[61].

IBD PATIENTS IN THE CLINICAL TRIALS

The purpose of the IBD clinical trial is to find the most effective and safest treatment. Currently there are several IBD clinical trials in process globally with hundreds of patients enrolled in them. The COVID-19 pandemic has made overall negative impacts on clinical trials due to disruptions, social distancing policies, travel limitations and delays in the supply of investigational medications. According to the CCFA, IBD patients currently enrolled in clinical trials should contact clinical research staff for updates regarding any changes to trials through emails or phone calls and try to delay the follow up visits and arrange for home drug delivery.

GUIDELINE TO MANAGING PREGNANT IBD PATIENTS DURING THE PANDEMIC

In non-pandemic times, the management of IBD can be broken down into three phases: Pre-conception, pregnancy period, and post-partum. Prior to conception, IBD care should focus on disease and medication management with the goals to maintain the patient in remission and maintaining medications that are safe in the event a patient becomes pregnant[62]. Medications for IBD are thought to be safe in pregnancy with the exception of methotrexate and thalidomide which are category X[64]. If a patient is on methotrexate, the medication must be stopped at least 3 months in advance before conception, while biologics and thiopurines are lower risk and can be continued during pregnancy. During pregnancy, patients should follow closely with their gastroenterologist and have monitoring for symptoms every two weeks. If there is a concern of a flare, diagnostic work-up includes labs, imaging, and endoscopy studies or surgery if severely toxic. Medication management is similar to non-pregnant women with the exception of usage of methotrexate, tofacitinib, and thiopurine usage in thiopurine-naïve patients[62].

During these pandemic times, there have been reports of vertical transmission of COVID-19 from an infected mother to the newborn and neonates with COVID-19 have had a range of outcomes[65,66]. Currently, there are no studies that have focused on the outcomes of pregnant women with IBD who have become infected with COVID-19 regarding IBD activity, pregnancy course, and neonatal health. The CCFA recommends continuing current IBD management with no changes in the setting of the pandemic and to work closely with gastroenterologists. Rosenet al[66]reviewed the management of acute severe UC in pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2. They describe a case of young woman who tested positive for COVID-19 with an UC flare and respiratory symptoms that was managed with intravenous cyclosporin 2 mg/kg since she was unable to transition to oral prednisone and azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine. Unfortunately, she had a spontaneous abortion during her hospital course[67]. There is no known optimal management of IBD pregnant women in this pandemic, but given current recommendations, the usage of biologics or cyclosporin may be used for salvage therapy while restricting steroid usage.

MENTAL HEALTH MANAGEMENT IN IBD PATIENTS DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The mental health and stress from the outbreak of COVID-19 can affect people of all ages. In those living with IBD, the severity of medical disease can greatly affect their mental health with the added stress of the COVID-19 pandemic. The CDC has recommended a range of therapies to cope with the stress of the pandemic including taking breaks from news stories, taking care of the body with breathing exercises, stretching, healthy eating habits, regular exercise, good sleep hygiene, and to avoid substances such as alcohol and drugs. They also recommend making time to unwind and to take time to connect with others[68]. In Italy, Saniet al[68]described that with protracted social isolation there will be concerns of an increase of disorders such as anxiety, mood, additive and thought disorders in patients' mental health during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the authors recommended active ongoing participation of mental health professionals during this critical period[69].

In IBD patients, there are no specific guidelines on the optimal management of mental health. However, the CCFA recommend the same guidelines as the CDC with turning off media and news updates, setting a schedule, regular stress management, connecting with family and friends, enforcing a daily routine, and making use of meeting with mental health professionals[70]. Additionally, patients with IBD should find support groups either locally or through online resources.

MANAGEMENT OF IBD PATIENTS WITH COVID-19

Recommendations for the management of IBD patients without a concern for an active COVID-19 infection have been to maintain medications if IBD disease activity is stable[72]. Additionally, patients should maintain these medications to avoid relapse and its consequences[35]. However, it is unclear the appropriate management of SARSCoV-2 positive IBD patients. Management of these patients can be divided into those with stable IBD disease or acute flares and further divided to patients with COVID-19 that are asymptomatic and symptomatic (Figure 3). Regardless of COVID-19 positivity, patients should adhere to strict social distancing per their local recommendations.

Quiescent IBD patient with active COVID-19

Since rapid testing has been increasing, patients with no or minimal symptoms may test positive for COVID-19. An expert commentary by Rubinet al[23]with the support of IOIBD stated that asymptomatic COVID-19-positive IBD patients should have their medications regimens changed to monitor for the development of symptoms. Specifically, monoclonal antibody therapies such as anti-TNF, ustekinumab, or vedolizumab held for 14 days with monitoring of COVID-19 symptoms and recommend reinitiating therapy after two weeks if these symptoms do not develop. Immunomodulators such as thiopurines, methotrexate, and tofacitinib should be held. However, stopping 5-aminosalicylates in patient who tested positive was felt to be inappropriate on the most recent survey by the IOIBD[23].

The IOIBD has different recommendations for IBD patients who develop symptomatic COVID-19. First off, survey participants of the IOIBD felt that it was inappropriate to hold 5-aminosalicylates and therefore were considered safe to continue. Monoclonal antibody therapy (such as anti-TNF and ustekinumab), immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate, and tofacitinib), and corticosteroids (prednisone greater than 20 mg per day) should be discontinued. It is uncertain whether vedolizumab or non-systemic corticosteroids (such as budesonide) should be held in setting of COVID-19[23]. There is no consensus on the timing of recommencement once infection occurred, but one recommendation by Al-Aniet al[12]stated to reinitiate IBD therapy once infection is cleared defined by two negative nasopharyngeal swabs 24 hours apart at least 8 days after symptoms or waiting at least 14 days after symptom onset and clinical improvement with resolution of fever for at least three days.

Acute flare with active COVID-19

Exacerbations of IBD have been rare, les s than 10 percent, during the pandemic; however, patients who develop flares may require endoscopic evaluation[72]. Given the concern of fecal-oral transmission with the detection of COVID-19 in stool specimens, there is a risk of transmission from patient to health-care provider[73,74]. Therefore, it is critical to ensure patients be tested or screened for COVID-19 prior to considering endoscopic evaluation or therapy.

In patients suspicious for flares,i.e.those with new abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fever, and COVID-19, treatment and evaluation should focus on evaluating gastroenterology symptoms which include ruling out enteric infections and confirming inflammation (with inflammatory markers such as fecal calprotectin or cross-sectional imaging like CT or MR enterography). To note, COVID-19 can illicit an inflammatory response on the gut therefore elevation of fecal calprotectin must be cautiously used to diagnose a flare and a threshold of < 100 mg/g should be used to rule out active inflammation[74]. If confirmed relapse, treatment focuses on the severity of flare and COVID-19. For mild COVID symptoms, flares should be treated as done as per usual. In more severe COVID symptoms, the risk-benefits must be weighed on starting IBD therapies, increasing therapy, or holding IBD therapy[35]. Steroids, specifically prednisone, should be decreased to the lowest possible dose (less than 20 mg per day) in non-severe cases as they are found to be associated with poor outcomes in SECURE IBD study and by expert opinion by Japan IBD COVID-19 task force[75,76]. However, patient with severe and progressive COVID-19 infection with requirement of mechanical ventilation current recommendations are to continue with IV steroids[30]. There is limited evidence of medications on COVID-19 and the risk of infection. The BSG reported that IBD medications including all classes of immunomodulators and biologics are safe with no added risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection[77]. However, with medications being trialed for the treatment of COVID-19, caution should be advised in IBD patients to avoid drug-drug interactions[12].

Figure 3 Simplified algorithm for management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

A well-known anti-malarial drug and treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and lupus that was used in the early stages of the pandemic was hydroxychloroquine/ chloroquine. This is an immunomodulator against cytokines that has interactions with other immunomodulators, such as methotrexate, azathioprine, and tofacinib. Concurrent chloroquine usage with thiopurines or methotrexate can have an increased risk of myelosuppression; therefore, it is recommended to stop thiopurines and methotrexate in the event of chloroquine usage. Furthermore, chloroquine may increase tofacitinib levels; however, the clinically significant of this is unknown[12]. Overall, hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine has quickly fallen out of favor given the cardiac complications[78].

Remdesivir, a nucleoside prodrug, has antiviral properties a broad spectrum of viruses[79]. There has been no medication interaction reported with concurrent usage of remdesivir with corticosteroids, thiopurines, methotrexate, tofacitinib, biologics or 5-ASA[12].

Kaletra (Lopinavir/Ritonvair) is a protease inhibitor used for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus. A randomized controlled open label trial involving a total of one hundred and ninety-nine patients with SARS-CoV-2 underwent randomization and ninety-nine patients received lopinavir-ritonavir. Results of the trial showed no benefits of lopinavir-ritonavir as compared to standard care[80]. However, interactions have been documented with steroids and tofacitinib, causing increased levels of both latter drugs. Furthermore, tofacitinib should be stopped if necessary. No interactions were noted with thiopurines, methotrexate, 5-ASA, or biologics[12].

POST COVID-19 INFECTION CARE IN IBD PATIENT

While the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve, there is speculation on care in the post-pandemic period. As stated earlier, IBD therapy resumption is thought to be safe once the COVID infection is cleared, defined by negative testing over an 8 days period or improving symptoms after 14 days of symptom onset without repeat COVID testing[12]and/or after 2 nasopharyngeal PCR tests are negative. However, for postinfection endoscopy, there are numerous barriers including the concern of fecal-oral transmission, prevention of outbreaks, and finally the waitlist from cancelled procedures[52,73]. Recommendations from experts including Iacucciet al[52]suggest prioritizing patients according to symptoms, lab testing, medications, surgical history, and cancer risk.

CONCLUSION

Management of IBD is unique and challenging especially during this unprecedented time. There is always a concern of increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 among IBD patients due to nature of the disease and use of immunosuppressive medications. However, it is clear from current guidelines and expert opinion that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in IBD patients is similar to that of the general population. Hence, those with IBD should continue immunomodulators and immunosuppressive agents except corticosteroids to prevent risk of flare and development of immunogenicity. Data from epicenters such as Milan and New York City, as well as the SECURE-IBD registry, show that older age, active IBD, co-morbid conditions and use of steroids are associated with risk of severe COVID-19 infection among IBD patients. Similarly, predictors of poor outcome of COVID-19 infection have been well documented in immunocompromised patients in the general population. Considering the current literature, gastroenterologists should focus on educating their IBD patients for measures to prevent infection such as universal precautions, use of telemedicine and deferring non-elective surgical and endoscopic procedures.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年5期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年5期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Effects of antithrombotic agents on post-operative bleeding after endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal neoplasms and polyps: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Comparing the incidence of major cardiovascular events and severe microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Current trend in the diagnosis and management of malignant pheochromocytoma: Clinical and prognostic factors

- Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of COVID-19 infection: Lessons for practitioners