Effects of herbal medicine in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Fariba Sadeghi, Seyed Mohammad Bagher Fazljou, Bita Sepehri, Laleh Khodaie, Hassan Monirifar, Mojgan Mirghafourvand

Effects of herbal medicine in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Fariba Sadeghi1, Seyed Mohammad Bagher Fazljou1, Bita Sepehri2, Laleh Khodaie3*, Hassan Monirifar4, Mojgan Mirghafourvand5

1Department of Iranian Traditional Medicine, School of Traditional Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran;2Liver and Gastrointestinal Diseases Research center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran;3Department of Traditional Pharmacy, Faculty of Traditional Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran;4Horticulture and Crops Research Department, East Azarbaijan Agricultural and Natural Resources Research and Education Center, Tabriz, Iran;5Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Pyrosis and regurgitation are the cardinal symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Several herbs have been used for treating gastrointestinal disorders worldwide. This systematic review was conducted to investigate the effects of medicinal herbs on gastroesophageal reflux disease and adverse events.MEDLINE (via PubMed; The United States National Library of Medicine, USA), Scopus, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, Magiran, and Scientific Information Database were systematically searched for human studies, without a time frame, using medical subject heading terms such as “gastroesophageal reflux disease”, “reflux”, “esophagitis” and “herbs”. Manual searches completed the electronic searches.Thirteen randomized controlled trials were identified, including 1,164 participants from 1,509 publications. In comparing herbal medicine to placebo, there were no significant differences in terms of heartburn (= 0.23 and 0.48), epigastric or abdominal pain (= 0.35), reflux syndrome (= 0.12), and effective rate (= 0.60), but there was a significant difference in terms of acid regurgitation (= 0.01). In comparing herbal medicine to drugs, there was a significant difference in terms of effective rate (= 0.001), and there was one trial that reported a significant difference in terms of epigastric pain (= 0.00001). Also, in comparing herbal medicine to drugs, there were no significant differences in terms of acid regurgitation (= 0.39).This meta-analysis showed that herbal medicines are effective in treating gastroesophageal reflux disease. Further standardized researches with a large-scale, multicenter, and rigorous design are needed.

Herbal medicine, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Randomized controlled trial, Acid regurgitation, Effective rate, Epigastric pain

This systematic review provides a comprehensive estimate of the application of herbal medicine in the management of gastroesophageal reflux diseasesymptoms. The results showed that herbal medicines have a positive efficacy in the treatment and relief of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms.

The first recorded prescription ofandfor treating gastrointestinal disorders in Persian medicine was in. It was compiled by Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya al-Razi (865–925 C.E.), known to the Latin world as Rhazes, an Iranian scientist. Then, Abu Rayhan al-Biruni (973–1048 C.E.), another Iranian scientist, in hisand his contemporary Abu Ali Sina (980–1032 C.E.), famed as Avi-cenna in Europe, in hisdescribed the use of single and combined forms ofandfor treating various disorders such as gastralgia, reflux, and dyspepsia. Jorjani (1042–1137 C.E.), another prominent scientist and physician in the medieval era in, which is now regarded as the largest Persian medical encyclopedia, explained the use of herbal medicines, such asand, for treating esophagus and stomach diseases. In(a pharmacopoeia by Mohammad Hosein Aghili Shirazi; 1670–1747 C.E.), a complete description of 1,700 monographs, including,,,, and, was provided.

Background

About 8% to 30% of Asians and 8.5% of Iranians suffer from uninvestigated dyspepsia [1, 2]. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is estimated to be 10%–20% in Western countries and 3%–7% in Asians [3–5]. In southern Iran, the prevalence of regurgitation, heartburn, and concurrent symptoms were reported to be 52%, 32%, and 24.4%, respectively [6]. The prevalence of GERD symptoms at least weekly was reported to be 10% to 25% in western countries [7–9].

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are used as an essential and custom cure for GERD. Although PPIs change the pH of the refluxrate, they do not stop reflux due to a mechanically or functionally incompetent lower esophageal sphincter [10]. PPIs may cause side effects. Because GERD is persistent and progressive, many patients prefer to use traditional medicine [11].

Classic herbs in Persian medicine have been used in treating GERD. The first recorded prescription of(mastaki or mastic) and(Itrifal Gheshnizi) for treating gastrointestinal disorders was in[12]. It was compiled by Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya al-Razi (865–925 C.E.), known to the Latin world as Rhazes, an Iranian scientist. Then, Abu Rayhan al-Biruni (973–1048 C.E.), another Iranian scientist, in hisand his contemporary Abu Ali Sina (980–1032 C.E.), famed as Avi-cenna in Europe, in hisdescribed the use of single and combined forms ofandfor treating various disorders such as gastralgia, reflux, and dyspepsia [14]. Jorjani (1042–1137 C.E.), another prominent scientist and physician in the medieval era in, which is now regarded as the largest Persian medical encyclopedia, explained the use of herbal medicines, such asand, for treating esophagus and stomach diseases [15]. In(a pharmacopoeia by Mohammad Hosein Aghili Shirazi; 1670–1747 C.E.), a complete description of 1,700 monographs, including,,, and, was provided [16]. The World Health Organization has reported that the use of herbal remedies has increased twofold to threefold compared to conventional drugs worldwide [17, 18]. In the primary healthcare system in developing countries, about 80% of patients continue to use traditional medicine. About 25% of drugs in the United States contain at least one herbal substance [19]. The World Health Organization encourages all countries to develop their complementary and traditional medicines and reinforces practitioners to follow that path [20].

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have been conducted to evaluate the effects of herbal medicines on gastrointestinal diseases [11, 19, 21–24]. For example, Salehi et al. reviewed the effects of herbal medicines on the treatment for GERD in human and animal studies [19]. They found that medicinal plants were more effective in treating GERD and helped manage histopathological changes related to GERD. Dai et al. evaluated the safety and efficacy of modified Chinese medicine preparation Banxia Xiexin decoction in treating GERD in adults [11]. They mentioned the potential effects of modified Banxia Xiexin decoction on the treatment for GERD. Teschke et al. studied the efficacy of different traditional Chinese medicine preparations [24]. They concluded that there was no sufficient available evidence to support the equivalency of herbal traditional Chinese medicine preparations to conventional GERD. Ling et al. reported that clsssical Chinese medicine preparation Wendan decoction had a consistent therapeutic efficacy on bile reflux gastritis and GERD [22]. Mogami et al. indicated that Rikkunshito (RKT) could improve adverse effects caused by various western drugs and achieve better results, not influencing the efficacy and bioavailability of western drugs [23].

In this meta-analysis, all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were reviewed. The role of herbal medicine in the management of GERD symptoms in humans and their adverse effects (if any) are presented.

Methods

Objective

The objective of this review was to determine the effects (benefits and harms) of herbal medicines on the treatment of adult patients with GERD and compare them to those prescribed with placebo or conventional western drugs.

Database and search strategies

Literature search. MEDLINE (via PubMed; The United States National Library of Medicine, USA), Scopus, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, and Persian databases (e.g., Magiran and Scientific Information Database), without a time frame, were searched. In this review, all RCTs that studied the efficacy of herbal medicine in patients 18 years and older and evaluated placebo or conventional therapy, both written in English and Persian, were enrolled. Searches were based on specified controlled terms, focusing mostly on “GERD” and relevant words, including medical subject heading terms when possible. Moreover, the variation of the words’ root, the related keywords, and Persian synonyms were searched. Traditional medicine references (Ayurveda, Persian, Chinese, etc.) were not searched independently. The searched terms were used individually or in combination with the title, abstract, and keywords, such as (“gastroesophageal reflux disease” OR “gastroesophageal reflux” OR “reflux” OR “esophagitis” OR “gerd” OR “heartburn”) AND (“herbal” OR “herbs” OR “phytotherapy” OR “herbal medicine” OR “extract”) AND (“randomized controlled trials” OR “clinical trials”).

Manual searches of the related literature completed the electronic searches. Also, clinical trial registries, such as the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, were searched to find unpublished studies. The references of the included articles were also assessed for relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population, intervention, comparison, and outcome. The population, intervention, comparison, and outcome for this review was defined as follows.

Types of participants. The participants were adult men and women 18 years and older who had classic symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation) of GERD.

Types of intervention. Herbal medicines were provided for the intervention group. Publications that have used herbal medicine as intervention were included in this study.

Types of control. Placebo or conventional Western drugs (omeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole (RPZ), mosapride, and alginic acid) were provided for the control group.

Types of outcome. The improvement of GERD symptoms was the primary outcome (scores, reflux, heartburn, non-cardiac chest pain, effective rate, etc.), and adverse event was the secondary outcome.

Exclusion criteria. Patients less than 18 years old, infants, pregnant and nursing women, and patients with severe disease were excluded from this study.

Study selection and data extraction

All trials that assessed GERD symptoms were reviewed. Also, an adverse event was the secondary outcome in this systematic review. A two-stage screening process was carried out by two researchers independently (F.S. and M.M.). At first, titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility. Then, data were extracted from all included studies (Table 1). One author extracted the data, and another author reassessed each included study and assayed the findings. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

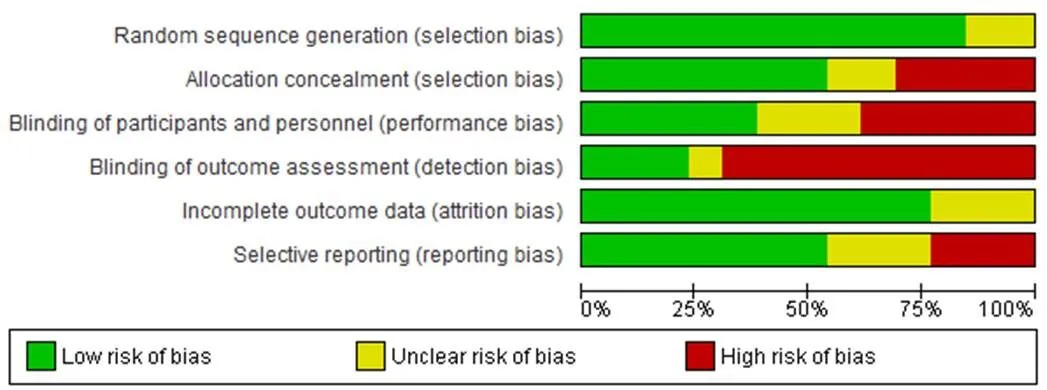

Assessment of risk of bias

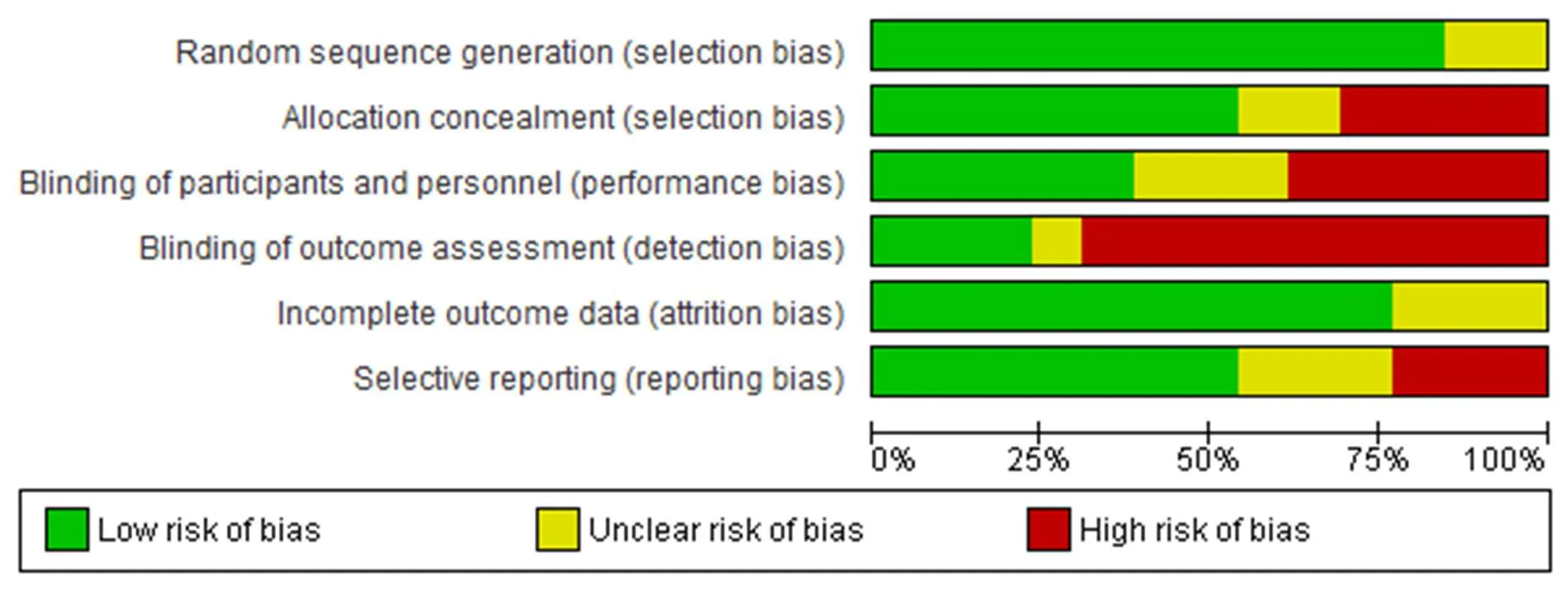

The Cochrane Collaboration tool was applied to assess the risk of bias in six domains in the included studies [25]. Each domain was evaluated in high, unclear, and low risks of bias. Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies and disagreement cases, and a third person who was specialized in this field helped them.

Data synthesis and analysis

The Review Manager Software version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Europe) was used to pool effect sizes. The mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD), odds ratio, and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated for the reporting of meta-analysis results. The I2index was used for the evaluation of heterogeneity in meta-analysis [26]. The random-effect model was used instead of the fixed-effect model when heterogeneity existed [27].

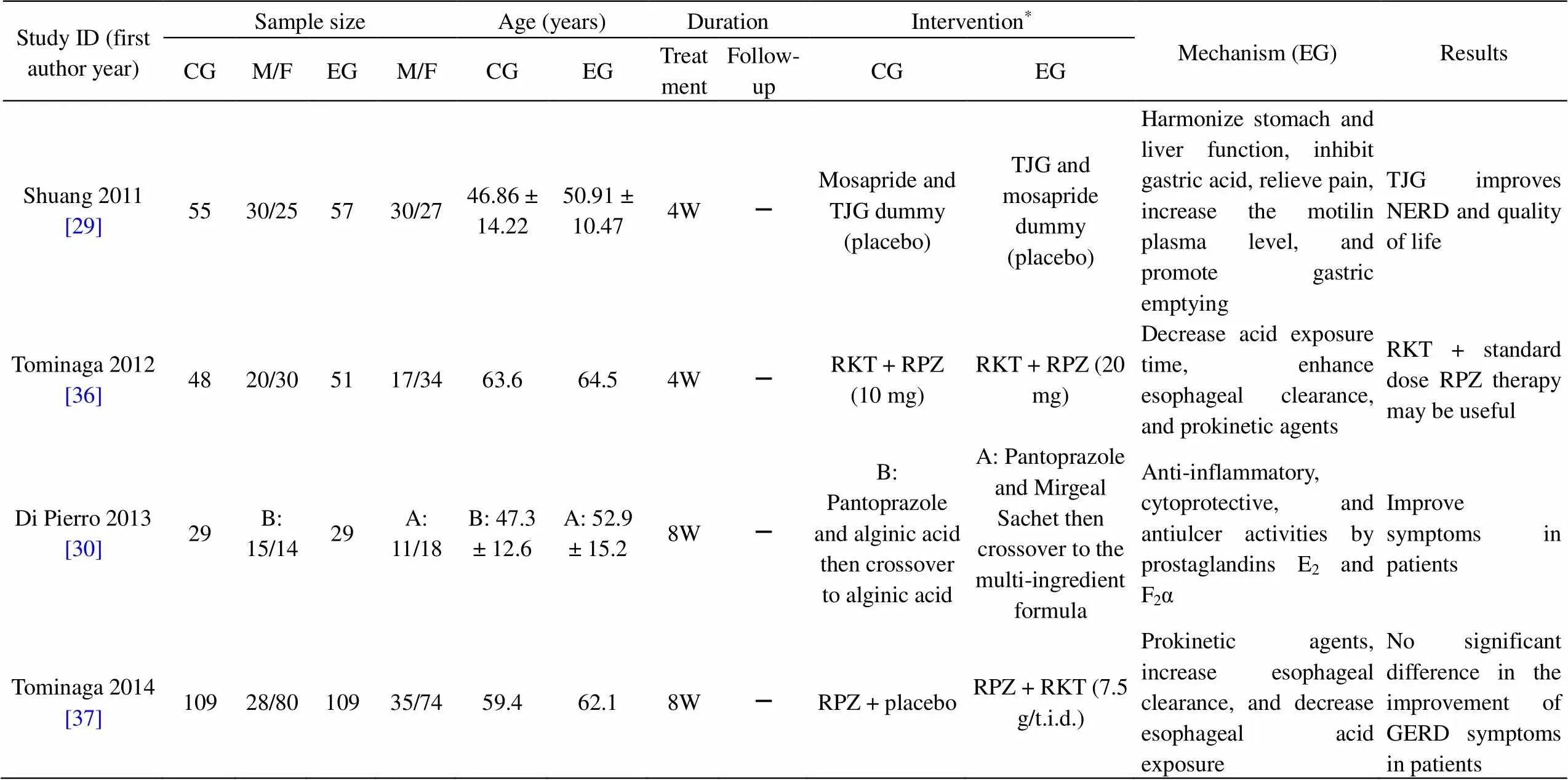

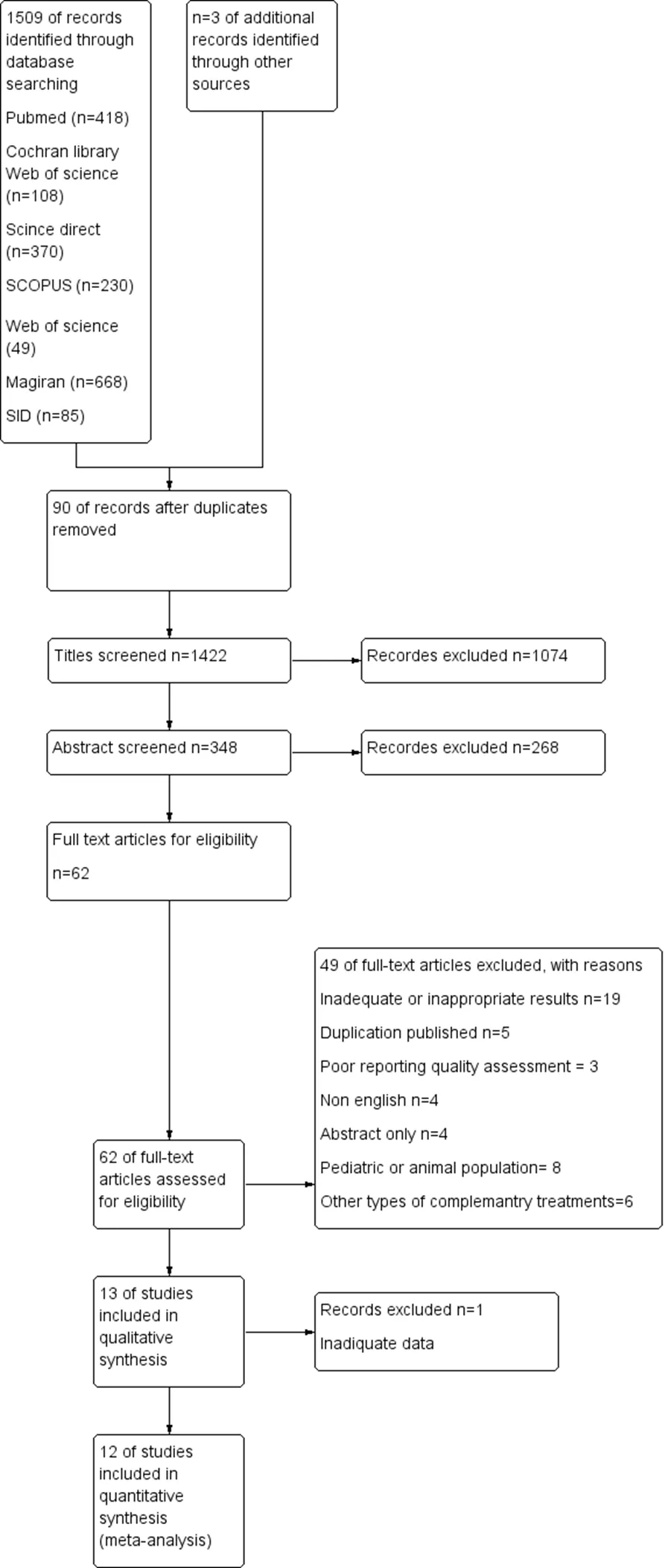

Table 1 Characteristics of the studies

Table 1 Characteristics of the studies (continued)

CG, control group; EG, experimental group; M, male; F, female; D, days; W, weeks; M, months; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease; RKT, Rikkunshito; RPZ, rabeprazole; TJG, Tongjiang granule; TJG, Tongjiang Granule; FSSG, Frequency Scale for Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease; RDQ, reflux diagnostic questionnaire; GERDQ, gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire; –, not mentioned.

*Details of interventions:

TJG,Tongjiang granule, contains(Perilla stem),, Os Sepiellae,, maltodextrin.

WCYT, Wuchuyu soup, contains(Juss) Benth,C.A. Meyer,Rose,Mill.

Mucosave sachet contains sodium alginate, Mucosave (verum), sodium bicarbonate.

Mirgeal sachet contains alginic acid, glycyrrhetinic acid, vaccinium myrtillus extract.

capsule containsMill,Rose,L. (Amla),Retz,.

Results

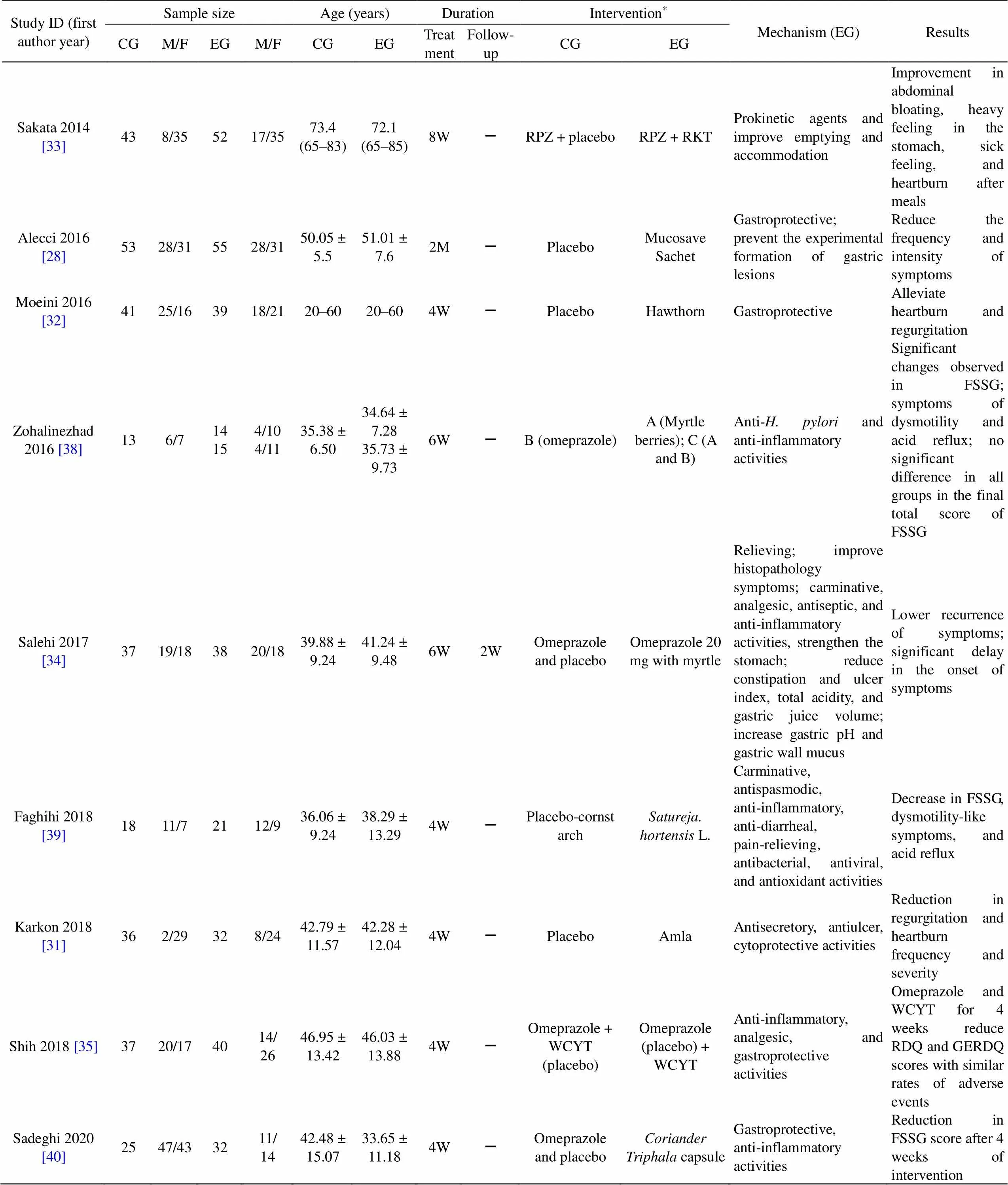

Study selection

A total of 1,509 records were achieved according to a systematic search. After screening, 13 studies (n = 1,164) had eligibility criteria and were included in this review [28–40]. Data of one study could not be included in the meta-analysis. The authors emailed to access the study data but did not receive any response [28]. Based on the objective, ultimately, 12 studies (n = 1,056) were entered into the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

In all studies, symptomatic GERD response was evaluated. The sample size ranged from 15 to 109 [37, 38]. The therapy period lasted from 4 weeks to 2 months in the included studies. The minimum age of the patients was 18 years old. The features of the included studies are available in Table 1.

Risk of bias in the included studies

In all 13 included studies, there was no significant difference in terms of baseline characteristics between the intervention and control groups. Eleven trials were described as double-blind, and one study was described as open-labeled [30]. Random sequence generation (selection bias) in two studies was unclear [32, 39]. Four studies had high-risk allocation concealment [30, 32, 33, 39]. Unclear allocation concealment (selection bias) was identified in two studies [29, 35]. Blinding of personal information and participants (performance bias) in five studies was a high risk [28, 30, 32–34]. Detection bias was low risk in two studies [26, 32]. Unclear attrition bias and high-risk reporting bias were other criteria for evaluating the risk of bias [28, 30, 33, 34, 38, 39].

Intention-to-treat analysis was performed in four studies, and three studies reported full analysis set [28, 29, 31, 33, 34, 37, 40]. One study reported an all-patient-treated analysis and a pre-protocol set analysis [29]. The randomization techniques used in the included RCTs were simple randomization, random number table, blokes of size 3 and 6, SAS and NCSS statistics software. In contrast, the other two studies did not report the specific randomization techniques [32, 38] (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were the scores of GERD symptoms. In various studies, different questionnaires have been used [28–40].

Alecci et al. used the gastroesophageal reflux disease-health-related quality of life (GERD-HRQL) and GERD symptom assessment scale questionnaires [28]. The GERD-HRQL questionnaire assesses heartburn severity in nine questions on a scale of 0 (no symptoms) to 5 (incapacitating). This validated instrument includes six heartburn-related items and questions relating to other GERD symptoms, medication use, and satisfaction with the present condition. The total GERD-HRQL score ranges from 0 to 50, with a higher score indicating more severe symptoms. The GERD symptom assessment scale is a self-administered questionnaire that asks the patient to report the frequency, severity, and degree of bother for 15 specific symptoms. Shuang et al. used “total score of symptoms” and “score of major symptoms” and “domain of SF-36” the previous week for the evaluation of the improvement of GERD [29]. The major symptoms referred to the reflux diagnostic questionnaire, which included retrosternal burning feeling or heartburn, chest pain, acid or bitter in the mouth, and uncomfortable nausea. Scores were given as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. The minor symptoms contained abdominal distension, acid reflux, belching, poor appetite, gastric upset, emotional irritability or depression, blocked sensation in the throat, stomach pain or bloating, and satiety and were scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3. Di Pierro et al. used a visual analog scale (0–10) for assessing the symptoms [30]. Karkon et al. measured on a frequency and severity scale the symptoms of GERD according to the quality of life in a reflux-associated disease questionnaire [31]. Salehi et al. used the Mayo Clinic standardized questionnaire [34]. Moeini et al. used a validated questionnaire to detect the severity of symptoms [32]. Shih et al. assessed the primary objectives using the reflux disease questionnaire and GERD questionnaire scores [35]. Six trials used the frequency scale for symptoms of GERD (FSSG) score to evaluate the intervention [33, 36–40]. The scores were calculated according to the frequency of the symptoms: 0, never; 1, occasionally; 2, sometimes; 3, often; and 4, always. Tominaga et al. assessed the symptoms in two domains: reflux symptom and acid-related dysmotility symptom domains; the total score was given by the sum of the two domains [36]. Sadeghi et al. assessed only the reflux symptom domain [40].

Figure 1 Flow chart of the included eligible studies in the systematic review

Despite different questionnaires, common outcomes, including total score, effective rate, regurgitation, heartburn, epigastric pain, and reflux syndrome, were used.

In 13 included studies, 1,164 participants (618 in the experimental groups and 546 in the control groups) were evaluated. In the included trials, PPIs, omeprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole, and other drugs, including mosapride, were used. The components of the prescriptions used in each literature are listed in Table 1.

This review carried out two categories as trials, such as herbal medicine versus placebo and herbal medicine versus classic drugs.

Figure 2 Risk of bias graph

Figure 3 Risk of bias summary

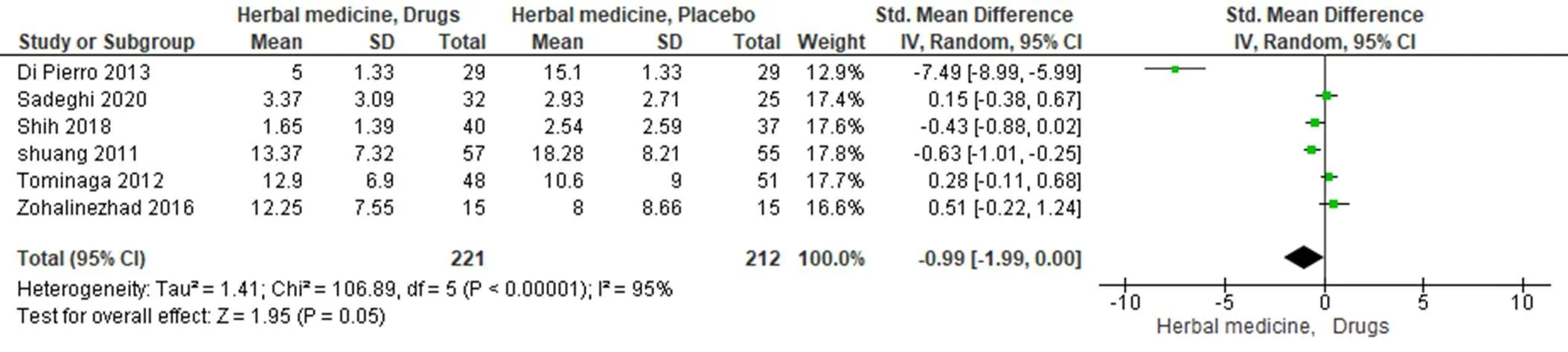

Total scores of symptoms. In the trials that compared the herbal medicines to drugs, six studies reported symptom scores. One of those was “total score of symptoms”, and the other three were “FSSG score” [29, 36, 38, 40]. One trial used GERD questionnaire, and another study used “mean global score” [30, 35]. A random-effect model (< 0.001, I2= 95%) and SMD were performed. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference in the improvement of total score between the experimental and control groups (SMD = −0.99, 95% CI = −1.99 to 0.00;= 0.05) (Figure 4).

Acid regurgitation. Two studies evaluated the improvement of acid regurgitation [30, 40]. Di Pierro et al. showed a statistically significant difference between Mirgeal + pantaprazole and drug (pantaprazole + alginic acid;= 0.001) [30]. However, no significant difference was observed between groups. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the improvement of acid regurgitation (MD = −1.02; 95% CI = −3.32 to 1.29;= 0.39).

In the herbal medicine versus placebo group, two studies that evaluated the improvement of acid regurgitation using hawthorn andshowed significant (= 0.02) and insignificant (= 0.26) difference, respectively [32, 34]. Because the data were dichotomous, the odds ratio was calculated. The reduction of regurgitation score showed a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups (odds ratio = 0.22; 95% CI = 0.07 to 0.70;= 0.01).

In the herbal medicine versus placebo group with continuous data, three studies evaluated the improvement of acid regurgitation using Amla, RKT, andL. [31, 33, 39]. Due to significant heterogeneity in the heartburn score (< 0.001, I2= 89%), a random-effect model was performed. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the improvement of acid regurgitation (MD = −0.37; 95% CI = −1.78 to 1.03;= 0.60) (Figure 5)

Heartburn (epigastric burning). Two studies reported heartburn [30, 40]. Di Pierro et al. showed a statistically significant difference between Mirgeal + pantaprazole and drug (pantaprazole + alginic acid) on the improvement of score (= 0.0005) [30]. The results prompted that there was no significant difference between theand omeprazole groups in the improvement of epigastric burning (= 0.58) [40].

In the herbal medicine versus placebo group, two studies reported epigastric burning (and hawthorn) [30, 34]. Due to heterogeneity, a random-effect model was used (= 0.05, I2= 74%). No significant difference was observed between the experimental and control groups in the improvement of epigastric burning (odds ratio = 0.32; 95% CI = 0.05 to 2.03;= 0.23).

In the herbal medicine versus placebo group with continuous data, four studies reported epigastric burning (Amla, RKT, and) [31, 33, 37, 39]. Due to significant heterogeneity in the regurgitation and heartburn score (< 0.001, I2= 93%), a random-effect model was performed. There was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and placebo groups in the improvement of epigastric burning (MD = −0.57; 95% CI = −2.15 to 1.01;= 0. 48).

Abdominal (epigastric, chest) pain. For the abdominal (epigastric, chest) pain, two trials were included [3, 33]. Both trials used RPZ + RKT as intervention, and RPZ + placebo was used as control. Because there was no significant heterogeneity (= 0.77, I2= 0%), a fixed-effect model was applied. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the improvement of abdominal (epigastric, chest) pain (MD = −0.11; 95% CI = −0.35 to 0.13;= 0.35). Di Pierro et al. showed a statistically significant difference between Mirgeal + pantaprazole and drug (pantaprazole + alginic acid) in the improvement of abdominal pain score (= 0.00001) [30].

Figure 4 Forest plot of comparison: effect of herbal therapy versus drugs on total scores. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 5 Forest plot of comparison: effect of herbal therapy versus placebo on acid regurgitation. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Effective rate. In the herbal medicine versus placebo group for effective rate, four trials were included [31, 33, 37, 39]. Amla, pantaprazole + RKT, pantaprazole + RKT, andL. were used as intervention, and placebo, pantaprazole + placebo, pantaprazole + placebo, and placebo were used as control, respectively. Due to significant heterogeneity (< 0.001, I2= 89%), a random-effect model was applied. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in effective rate (MD = −0.37; 95% CI = −1.78 to 1.03;= 0.60) (Supplementary Figure 1).

In the herbal medicine versus classic drugs group for effective rate, six trials were included [29, 30, 35, 36, 38, 40]. Due to significant heterogeneity (= 0.0006, I2= 77%), a random-effect model was applied. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the improvement of effective rate (MD = 0.18; 95% CI = 0.19 to −0.24 to 0.59; P = 0.40) (Supplementary Figure 2).

Reflux syndrome. For reflux syndrome, three trials were included [33, 37, 39]. In the three trials, pantaprazole + RKT, pantaprazole + RKT, andL. were used as intervention, and pantaprazole + placebo, pantaprazole + placebo, and placebo were used as control, respectively. Because there was no significant heterogeneity (= 0.21, I2= 36%), a fixed-effect model was applied. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the improvement of reflux syndrome (MD = 0.44; 95% CI = −0.12 to 1.00;= 0.12) (Supplementary Figure 3).

In the herbal medicine versus classic drugs group for reflux syndrome, six trials were included [29, 30, 35, 36, 38, 40]. Tongjiang granule (TJG), Mirgeal, Wuchuyu soup, RKT + RPZ 20 mg, andL.,were used for the experimental group, and mosapride citrate, alginic acid, omeprazole, RKT + RPZ 10 mg, omeprazole, and omeprazole were used as control, respectively. Due to significant heterogeneity (< 0.001, I2= 94%), a random-effect model was applied. Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the improvement of reflux syndrome (MD = 0.27; 95% CI = −2.50 to 3.03;= 0.85) (Supplementary Figure 4).

Secondary outcome

Adverse events. Of all included RCTs, seven studies reported adverse reactions during the treatment period [29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 40]. Overall, two trials mentioned no adverse events [28, 30]. In four articles, there were no discussions about adverse effects [33, 36, 38, 39]. The adverse effects are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Discussion

Possible explanation of the findings

PPIs and histamine 2 receptor blockers are used in treating GERD [36]. However, the daily use of a standard dose of PPIs has not been able to clinically eliminate GERD symptoms in 20% to 30% of patients [4, 37]. Furthermore, many patients should receive these medications in the long term or even lifetime, which causes side effects such asinfections, kidney problems, hip fractures, and respiratory infections, and the symptoms easily relapse after stopping PPIs [41–47]. As conventional treatments often remain unsatisfactory, a growing interest has been developed in herbal medicine, and up to 50% of patients seek other therapies, such as complementary and alternative medicine [48–50].

Of the 13 included RCTs, the efficacy of herbal medicine in treating GERD symptoms was compared to PPIs in 6 trials [30, 34–36, 38, 40]. In all 6 RCTs, herbal medicines were at least as effective as or even superior to PPIs.

In the placebo group, Sakata et al. reported that the degree of improvement of total and acid reflux disease scores of FSSG after 8-week treatment was significantly greater in the RKT group (RPZ 10 mg/q.d. + RKT 7.5 g/t.i.d.) than in the placebo (RPZ + placebo) group [33].

Various herbal medicines can play an important role ineradication. Only one trial discussed[33]. In this review, two herbal medicines,L. (Mirgeal) and hawthorn, were significantly effective in the amelioration of some GERD symptoms [30, 32]. Mirgeal was effective in the improvement of abdominal pain.L. and hawthorn were effective in the improvement of acid regurgitation.

is composed of the fruits of three herbal plant trees:L. (Amla),Retz., andRetz. [51]. Triphala possesses anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antiulcer, antiviral, and antibacterial properties [52–55]. Although Triphala has a long history in many different therapeutic applications in Persian traditional medicine (PTM) and Ayurvedic medicine, such as the treatment for digestive disorders, its combination with coriander (as) is unique to PTM. Sadeghi et al. observed 80% and 83.33% improvement in reflux symptom and FSSG scores, respectively, in patients who receivedas an intervention [40]. Patients in this group showed a significant decrease in heartburn and acid in the throat after treatment with.

In one study, the effectiveness ofas an anti-inflammatory factor, as well as an antifungal, pain-relieving, carminative, antibacterial, anti-diarrheal, antiviral, and antioxidant medication, has been shown [39].

RKT, which has prokinetic properties, has been shown to improve gastric fundus relaxation, which increases gastric storage capacity. Also, it facilitates the emptying of the stomach [33]. It acts through nitrergic and serotonergic pathways. In the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, RKT suppresses the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone, and therefore cortisol plasma levels under stress conditions, and reverses the increases of the neuropeptide Y plasma level, a neurotransmitter in the brain and autonomic nervous system [36, 37, 56].L. (myrtle) has anti-and anti-inflammatory activities [38]. Myrtle acts as a carminative, analgesic, astringent, and demulcent agent; it possesses anti-inflammatory and antiseptic properties. Based on PTM texts, myrtle reinforces the stomach and improves the LES. Constipation exacerbates reflux, and myrtle reduces constipation [34].

The functions of TJG are inhibiting gastric acid, and relieving pain. TJG can enhance the motilin plasma level, decrease the gastric acid level, and improve gastric emptying [29].

extract has anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective, and antiulcer properties. Licorice causes potassium loss and weight gain and increases blood pressure. All its side effects are due to the increase of sodium retention induced by glycyrrhetinic acid. It prolongs the presence of prostaglandins E2and F2α on the gastric mucosa [30].

Flavonoids, procyanidins, anthocyanidins, and phenolic acids are effective chemical compounds of hawthorn fruit [32]. Moreover, the doses of the medicines and the frequencies and methods of administration were different among these trials.

Quality of the evidence

Single center, small sample size, short duration of treatment and follow-up, attrition bias, missing data, and various interventions are the limitations of this review. Follow-up visits (2 weeks) have been reported in only one trial [34]. The treatment courses in the 13 studies ranged from 4 to 8 weeks. Dropouts in three trials were unexplained [30, 33, 38]. Missing data were not evaluated by intention-to-treat analysis in seven trials [30, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 39]. Furthermore, herbs under consideration are not available in other countries.

Conclusion

Herbal medicines have been used to manage different diseases worldwide since ancient times. The results of the clinical trials confirmed the effect of herbal medicines for treating GERD symptoms. Evidence from this review showed that herbal medicines in simple and combined forms have a positive efficacy in the treatment and relief of GERD symptoms. Therefore, medicinal plants can be used as a large source of medications independently or as an additional agent in managing gastrointestinal diseases. However, due to the poor methodological quality and small sample size of the included studies, further multicenter, large-scale, and large-sample-size investigations should be done.

1. Barzkar M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Habibi M, et al. Uninvestigated dyspepsia and its related factors in an Iranian community. Saudi Med J 2009, 30: 397–402.

2. Ghoshal UC, Singh R, Chang FY, et al. Epidemiology of uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia in Asia: facts and fiction. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011, 17: 235–244.

3. Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013, 108: 308–328.

4. Ren LH, Chen WX, Qian LJ, et al. Addition of prokinetics to PPI therapy in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20: 2412–2419.

5. Vakil N. Disease definition, clinical manifestations, epidemiology and natural history of GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010, 24: 759–764.

6. Khodamoradi Z, Gandomkar A, Poustchi H, et al. Prevalence and correlates of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Southern Iran: pars cohort study. Middle East J Dig Dis 2017, 9: 129–138.

7. Delavari A, Moradi G, Birjandi F, et al. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in the Islamic Republic of Iran: a systematic review. Middle East J Dig Dis 2012, 4: 5–15.

8. Leiman DA, Riff BP, Morgan S, et al. Alginate therapy is effective treatment for GERD symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 2017, 30: 1–9.

9. Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Mofid A, Ghotbi MH, et al. Epidemiological study of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: reflux in spouse as a risk factor. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008, 28: 144–153.

10. Herbella FA, Patti MG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: from pathophysiology to treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2010, 16: 3745–3749.

11. Dai Y, Zhang Y, Li D, et al. Efficacy and safety of modified Banxia Xiexin decoction (decoction for draining the heart) for gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2017, 2017: 9591319.

12. Razi A. Liber medicinalis almansoris. Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences Publications, 2008.

13. Zaydan J. History of Islamic civilization. Tehran: Amir Kabir Publication, 2008.

14. Avecinna H. Canon of medicine. New Delhi: Jamia Hamdard Press, 1998.

15. Jorjani E. Treasure of Kharazm Shah. Tehran: Iranian Medical Academy, 2001.

16. Aghili Khorasani MH. Storehouse of medicaments. Tehran: Tehran Univercity of Medical Sciences, 2011.

17. Pal SK, Shukla Y. Herbal medicine: current status and the future. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2003, 4: 281–288.

18. Thavorn K, Mamdani MM, Straus SE. Efficacy of turmeric in the treatment of digestive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst Rev 2014, 3: 71.

19. Salehi M, Karegar-Borzi H, Karimi M, et al. Medicinal plants for management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review of animal and human studies. J Altern Complement Med 2017, 23: 82–95.

20. Mosaddegh M, Shirzad M, Minaii MB, et al. Jovārish-e Jālīnūs, the herbal treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease in the history of medicine. J Res Hist Med 2013, 2: 1–10.

21. Guo Y, Zhu J, Su X, et al. Efficacy of Chinese herbal medicine in functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Tradit Chin Med Sci 2016, 3: 147–156.

22. Ling W, Huang Y, Xu JH, et al. Consistent efficacy of Wendan decoction for the treatment of digestive reflux disorders. Am J Chin Med 2015, 43: 893–913.

23. Mogami S, Hattori T. Beneficial effects of rikkunshito, a Japanese kampo medicine, on gastrointestinal dysfunction and anorexia in combination with Western drug: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2014, 2014: 519035.

24. Teschke R, Wolff A, Frenzel C, et al. Herbal traditional Chinese medicine and its evidence base in gastrointestinal disorders. World J Gastroentrol 2015, 21: 4466–4490.

25. Cochrane Collaboration [Internet]. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. (Version 5.1.0) [June 2020]. Available from: http://www. cochrane-handbook.org.

26. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327: 557–560.

27. Cochrane Collaboration [Internet]. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5.1.0) [cited June 2020]. Available from: http://www. cochrane-handbook.org.

28. Alecci U, Bonina F, Bonina A, et al. Efficacy and safety of a natural remedy for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux: a double-blinded randomized-controlled study. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2016, 2016: 2581461.

29. Li BS, Li ZH, Tang XD, et al. A randomized, controlled, double-blinded and double-dummy trial of the effect of Tongjiang granule on the nonerosive reflux disease of and Gan-Wei incoordination syndrome. Chin J Integr Med 2011, 17: 339–345.

30. Di Pierro F, Gatti M, Rapacioli G, et al. Outcomes in patients with nonerosive reflux disease treated with a proton pump inhibitor and alginic acid ± glycyrrhetinic acid and anthocyanosides. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2013, 6: 27–33.

31. Karkon Varnosfaderani S, Hashem-Dabaghian F, Amin G, et al. Efficacy and safety of amla (L.) in non-erosive reflux disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Integr Med 2018, 16: 126–131.

32. Moeini F, Jafarian AA, Aletaha N, et al. The effects of hawthorn () syrup on gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Iran J Pharm Sci 2016, 12: 69–76.

33. Sakata Y, Tominaga K, Kato M, et al. Clinical characteristics of elderly patients with proton pump inhibitor-refractory non-erosive reflux disease from the G-PRIDE study who responded to rikkunshito. BMC Gastroenterol 2014, 14: 116.

34. Salehi M, Azizkhani M, Mobli M, et al. The effect ofL. syrup in reducing the recurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Iran Red Crescent Med 2017, 19: e5755657.

35. Shih YS, Tsai CH, Li TC, et al. Effect of wu chu yu tang on gastroesophageal reflux disease: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine 2019, 56: 118–125.

36. Tominaga K, Iwakiri R, Fujimoto K, et al. Rikkunshito improves symptoms in PPI-refractory GERD patients: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2012, 47: 284–292.

37. Tominaga K, Kato M, Takeda H, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of rikkunshito for patients with non-erosive reflux disease refractory to proton-pump inhibitor: the G-PRIDE study. J Gastroenterol 2014, 49: 1392–1405.

38. Zohalinezhad ME, Hosseini-Asl MK, Akrami R, et al. Myrtus communis L. freeze-dried aqueous extract versus omeprazol in gastrointestinal reflux disease: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. J Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2016, 21: 23–29.

39. Faghihi-Kashani AH, Heydarirad G, Yousefi SS, et al. Effects of “L.” on improving adult gastrosophageal reflux disease: a double-blinded, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Iran Red Crescent Med 2018, 20: e57953.

40. Sadeghi F, Fazljou SMB, Sepehri B, et al. Effects ofandon adult gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized double-blinded clinical trial. Iran Red Crescent Med 20, 2020: 22: e102260.

41. Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, et al. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. New York: Mcgraw-Hill Medical, 2012.

42. Deshpande A, Pant C, Pasupuleti V, et al. Association between proton pump inhibitor therapy andinfection in a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012, 10: 225–233.

43. Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open 2015, 3: e166–171.

44. Eom CS, Park SM, Myung SK, et al. Use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of fracture: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Fam Med 2011, 9: 257–267.

45. Eom CS, Jeon CY, Lim JW, et al. Use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2011, 183: 310–319.

46. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2015, 10: e0128004.

47. Yamashita H, Okada A, Naora K, et al. Adding Acotiamide to gastric acid inhibitors is effective for treating refractory symptoms in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 2019, 64: 823–831.

48. Miwa H, Kusano M, Arisawa T, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol 2015, 50: 125–139.

49. Vanheel H, Tack J. Therapeutic options for functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis 2014, 32: 230–234.

50. Lahner E, Bellentani S, Bastiani RD, et al. A survey of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders. United European Gastroenterol J 2013, 1: 385–393.

51. Baliga MS. Triphala, Ayurvedic formulation for treating and preventing cancer: a review. J Altern Complement Med 2010, 16: 1301–1308.

52. Kalaiselvan S, Rasool MK. Triphala herbal extract suppresses inflammatory responses in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages and adjuvant-induced arthritic rats via inhibition of NF-κB pathway. J Immunotoxicol 2016, 13: 509–525.

53. Shakouie S, Eskandarinezhad M, Gasemi N, et al. An in vitro comparison of the antibacterial efficacy of Triphala with different concentrations of sodium hypochlorite. Iran Endod J 2014, 9: 287–289.

54. Nariya MB, Shukla VJ, Ravishankar B, et al. Comparison of gastroprotective effects of Triphala formulations on stress-induced ulcer in rats. Indian J Pharm Sci 2011, 73: 682–687.

55. Saxena S, Lakshminarayan N, Gudli S, et al. Anti-bacterial efficacy of,,and Triphala on salivarycount-A linear randomized cross over trial. J Clin Diagn Res 2017, 11: ZC47–ZC51.

56. Tominaga K, Sakata Y, Kusunoki H, et al. Rikkunshito simultaneously improves dyspepsia correlated with anxiety in patients with functional dyspepsia: a randomized clinical trial (the DREAM study). Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018, 30: e13319.

:

Study concept and design: Laleh Khodaie, Seyed Mohammad Bagher Fazljou, Bita Sepehri, and Fariba Sadeghi. Analysis and interpretation of data: Fariba Sadeghi, Mojgan Mirghafourvand, and Hassan Monirifar. Drafting and revision of the manuscript: Fariba Sadeghi, Mojgan Mirghafourvand, Laleh Khodaie, and Hassan Monirifar. Statistical analysis: Hassan Monirifar.

:

The authors are thankful to Dr. Hamideh Sedighzadeh, from USA for comments that significantly improved the manuscript editing. We would like also to show our gratitude to Mona Nasir Zonouzi, Optometry Graduate Students Association, Canada for sharing her pearls of wisdom with us through the progress of this study.

:

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; RKT, Rikkunshito; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; RPZ, rabeprazole; MD, mean difference; SMD, standardized mean difference; CI, confidence interval; FSSG, frequency scale for symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease; GERD-HRQL, gastroesophageal reflux disease-health-related quality of life; TJG, Tongjiang granule; WCYT, Wuchuyu soup; PTM, Persian traditional medicine.

:

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

:

Fariba Sadeghi, Seyed Mohammad Bagher Fazljou, Bita Sepehri, et al. Effects of herbal medicine in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Traditional Medicine Research 2020, 5 (6): 464–475.

:Jing-Na Zhou.

: 18 June 2020,

9 September 2020,

:27 October 2020

Laleh Khodaie, Department of Traditional Pharmacy, Faculty of Traditional Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Univesity Main Sreet, Tabriz, Iran.

10.12032/TMR20200929200

Traditional Medicine Research2020年6期

Traditional Medicine Research2020年6期

- Traditional Medicine Research的其它文章

- Is “Pangolin (Manis Squama) is not used in medicine" an improvement in the protection of precious and rare species or an improvement in the safety of using medicine?

- The gap between clinical practice and limited evidence of traditional Chinese medicine for COVID-19

- The potential effects of Caper (Capparis spinosa L.) in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy